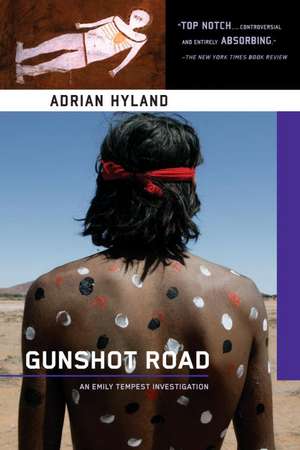

Gunshot Road: Emily Tempest Investigation (Paperback)

Autor Adrian Hylanden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2011

Preț: 93.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 140

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.91€ • 18.78$ • 14.91£

17.91€ • 18.78$ • 14.91£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781569479421

ISBN-10: 1569479429

Pagini: 372

Dimensiuni: 129 x 191 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

Seria Emily Tempest Investigation (Paperback)

ISBN-10: 1569479429

Pagini: 372

Dimensiuni: 129 x 191 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

Seria Emily Tempest Investigation (Paperback)

Notă biografică

Adrian Hyland won Australia's Ned Kelly 2007 Award for Best First Novel for Moonlight Downs. He spent many years in the Northern Territory living and working among the indigenous people. He now teaches at LaTrobe University and lives in Melbourne.

Extras

INITIATIONS

I CLOSED MY eyes, felt the ragged harmonies flowing through my head.

Pitch dark, but the dawn couldn’t be far off. Hazel on the ground beside me, singing softly. Painted sisters dancing all around us, dust swirling up from bare feet. Cocky feathers catching firelight. Coloured skirts, circles and curves.

It was Young Man’s Time in Bluebush. Boys were being made into men. Here in the women’s camp, we were singing them goodbye.

The men were a couple of hundred yards to the west: a column of ghostly figures weaving in and out of a row of rattling branches. Clapsticks and boomerangs pounded the big bass rolling rhythm of the earth.

Gypsy Watson, our boss, the kirta, struck up another verse of the fire song: ‘Warlu wiraji, warluku…’

The rest of us tagged along behind.

My breasts, cross-hatched with ochre, moved gently as I turned and took a look around.

You couldn’t help but smile. The town mob: fractured and deracinated they might have been, torn apart by idleness and violence, by Hollywood and booze. But moments like these, when people came together, when they tried to recover the core, they gave you hope.

It was the songs that did it: the women didn’t so much sing them as pick them up like radio receivers. You could imagine those great song cycles rolling across country, taking their shape from what they encountered: scraps of language, minerals and dreams, a hawk’s flight, a feather’s fall, the flash of a meteorite. The resonance of that music is everywhere, even here, on the outskirts of the whitefeller town, out among the rubbish dumps and truck yards. It sings along the wires, it rings off bitumen and steel.

A disturbance—a slurred, drunken scream—somewhere to my right.

Maybe I spoke too soon.

Two women were yelling at each other. One was sitting down, obscured by the crowd. The other was all too visible: Rosie Brambles, looking like she’d just wandered out of the Drunks’ Camp.

Rambling Rosie, her dress a hectic red, her headscarf smeared with sweat and grease: she was built like a buffalo, with broad shoulders and spindly legs. She was drunk and angry. Nothing unusual in that; Rosie was mostly drunk and often angry, but this wasn’t the place for it.

Her antagonist was Cindy Mellow—mellow by name, far from it by nature—a manky-haired little spitfire from Curlew Creek. Sounded like their argument was about a bloke. Still nothing unusual. Rambling Rosie’s life was a succession of layabout lovers, black, white and every shade between. Cindy was being held back by her aunties, but they couldn’t hold her mouth: she cut loose with a string of insults, one of which was about a baby.

Rag to a bull, that. Years ago, one of Rosie’s babies had been found—alive, by chance—abandoned in a rubbish bin.

Rosie erupted: ‘Ah, you fuckin little bitch!’ She ran to a fire, grabbed a branch of burning lancewood, came back swinging.

Old ladies scattered, little kids screamed.

I jumped to my feet.

‘Rosie…’

She held the branch like a baseball bat, oblivious.

I moved closer, one arm extended.

‘Rosie!’ I raised my voice. ‘Settle down…’

She looked around. Gunpowder glare. No recognition. Then she rushed at me with a savage swing of the brand. I curved back and it swept past my head, sent a shower of sparks and a blast of heat into my face. I smelled my own hair, smoking.

I’d thought I was ready for her, a part of me was. But another part was mesmerised, staring with dazzled fascination at the river of light the torch left in its wake. In that shimmering arc I saw galaxies and golden fish, splinters and wings, crystal chips. I saw the song we’d just been singing.

‘Emily!’ Hazel’s warning scream.

I rolled out of the way as the fire swept past my head.

Enough was enough.

I snatched up a crowbar one of the old ladies had left behind. When Rosie came at me a third time I planted the crowie in the ground. The brand crashed into it with another explosion of sparks as I pivoted on the bar, slammed a thudding double-kick into her chest. She staggered backwards, hit the dirt. Suddenly still. Looked up, confused, winded, heaving.

Christ, Rosie. Don’t have a heart attack on me. My first day on the job and they’ll have me up on a murder charge.

Hazel came stomping over. ‘What you doing, Rosie? Running round fighting, putting the wind up these old ladies and little girls!'

Rosie raised herself onto an elbow, stared at the ground, shamefaced. Finished, the fight knocked out of her. The women began to make their way back to their places. But I glanced at Gypsy Watson, saw that she was troubled.

I knelt beside her, put a hand on her knee. ‘Don’t worry, Napurulla. It’s over now…’

She looked out over the dancing ground, her mouth at a downward angle. I followed her gaze. Rosie lurching off into the shadows. One of the teenage girls swaying under a set of headphones, travelling to the beat of a different drum. Cans of Coke, crucifixes and wristwatches, corrugated iron, powdered milk. In the distance the whitefeller lights of Bluebush cast an ugly orange pallor into the sky.

Gypsy was a Kantulyu woman, grown to adulthood in the desert out west. Hadn’t seen a whitefeller until she was in her twenties. Last year, one of her grandsons hanged himself in the town jail. A couple of months ago her brother Ted Jupurulla, one of the main men round here, died of cancer—a long, horrible death. She’d been in mourning ever since.

She was watching her world fall apart.

‘Over?’ she intoned wearily, shaking her head. ‘Yuwayi,’ she crackled, ‘but what over? They killin us with their machine dreams and poison. Kandiyi karlujana…’

The song is broken.

Which song? The one we’d just been singing, or the whole bloody opera? I gave her a hug, stood up, moved to the back of the crowd. The ceremony slowly resumed, other women took up the chant. But something was missing.

Somewhere among the hovels a rooster crowed. Didn’t necessarily mean the approach of dawn—that bird’s timing had been out of whack since it broke into Reggie Tapungati’s dope stash— but it was a reminder. Time to be on my way. McGillivray had said he wanted me there at first light.

I threw a scrap of turkey, a lump of roo-tail and an orange into my little saddlebag and headed for the track to town.

SCORCHER

I'D ONLY GONE a few yards when I became aware of bare feet padding up behind me.

Hazel, her upper body adorned with ochre, feathers in her hair, a friendly frown.

‘Sneakin off, Tempest?’

‘Didn’t want to disturb you.’

She grinned. ‘Disturb us? Heh! Even a tempest’d be peaceful after Rosie. You gotta go so early?’

‘Tom told me to be there first thing. Don’t want to give him or his mates the satisfaction of seeing me late for my first day at work. Especially the mates—’

She studied the distant town, a troubled expression on her face.

Somewhere out on Barker’s Boulevard a muscle car pitched and screamed: one of the apprentices from the mine. Apprentice idiot, from the sound of him. A drunken voice from the whitefeller houses bayed at the moon. A choir of dogs howled the response.

‘You sure you know what you’re doin? This…job?’ Her lips curled round the word like it had the pox.

‘Dunno that I ever know what I’m doing, Haze. I’ve said I’ll give it a go.’

She smiled, sympathetic. She knew my doubts better than I knew them myself; she’d been watching them play themselves out for long enough—since we were both kids on the Moonlight Downs cattle station, a couple of hundred k’s to the north-west. I’d flown the coop early, gone to uni, seen the world. Hazel had never left.

The little community there had hung on over the years, through the usual stresses endured by these marginal properties on the edge of the desert. It had held together, like some sort of ragged-arse dysfunctional family, thanks in large part to the influence of Hazel’s dad Lincoln Flinders and the efforts of Hazel herself.

Lincoln was dead now, savagely murdered not long ago. Just around the time I’d returned myself, come back from my restless travels and fruitless travails. Come home, hoping to find something, not knowing what.

I had a better idea now, though.

We’d taken the first tentative steps to independence: built a few rough houses, put in a water supply, planted an orchard. Our mate Bindi Watkins had started a cattle project, and was managing, in the main, to keep the staff from eating the capital. There was talk of a school, a store, a clinic.

The one thing we lacked was paid employment. So when Tom McGillivray, superintendent of the Bluebush Police and an old friend of the Tempest clan, came up with the offer of an Aboriginal Community Police Officer’s position we were happy to accept.

The only complication was the person he insisted on filling the position.

‘Join the cops, Emily!’ Hazel was still shocked.

‘Not real cops, Haze. ACPOs can only arrest people. I won’t be shooting anyone.’

‘Yeah but workin with them coppers…Old Tom, ’e’s okay—we know im long time. Trust im. But them other kurlupartu…’

I’d been wondering myself how McGillivray’s hairy-backed offsiders would react to a black woman in their midst.

‘Bugger em,’ I said with a bravado I wished I felt. ‘It’ll be an education.’

‘Yuwayi, but who for?’

‘It’s only a few weeks, Haze.’

That was the deal: a month in town, working alongside Bluebush’s finest, then I’d be based at Moonlight. I’d just come back from a short training course in Darwin in time to catch the tail end of the initiation rites.

The clincher in the deal—and this wasn’t just the cherry on top, it was the whole damn cake and most of the icing— was a big fat four-wheel-drive. Government owned, fuelled and maintained. The community was tonguing at the prospect; the goannas of Moonlight Downs wouldn’t know what hit em.

We paused at the perimeter of the town camp, looked back at the fire-laced ceremony. A chubby toddler broke free from the women, wobbled off in the direction of the men, his little backside bobbing. He hesitated, lost his nerve and rushed back into the comforting female huddle.

They all laughed. So did we, the sombre mood evaporating. Say what you like about me and my mob, there’s one thing you can’t deny: we’re survivors. You can kick us and kill us and drown us in bible and booze, but you better get used to us because we’re not going away.

‘So you’re out bush, first day?’

‘Tom got the call last night. Some old whitefeller killed at the Green Swamp Well Roadhouse.’

‘What happen?’

‘Dunno. Probably bashed to death with a cricket bat—deadly serious about their sport out there.’

Green Swamp Well’s main claim to fame—apart from the world’s biggest collection of beer coasters and mooning photos, its tough steaks and tougher coffee—was the annual Snowy Truscott Memorial Cricket Match.

Hazel glanced at the eastern sky. ‘Gonna be a scorcher.’

She was right: the drop of rain we’d had yesterday would only add to the humidity, and the radio predicted a brutal 45 degrees. Performing any sort of outdoor activity today would be like doing laps in a pressure cooker.

We were in the middle of the build-up. That time of year temperate Australia thinks of as spring: after the winter dry and not yet properly into the wet, when temperatures, tempers and the odd bullet go through the roof and the rain is always somewhere else. You’d be out of your mind if you didn’t go a little bit crazy.

‘Look after yourself,’ said Hazel. She kissed me on the cheek, returned to the dancing ground.

I CLOSED MY eyes, felt the ragged harmonies flowing through my head.

Pitch dark, but the dawn couldn’t be far off. Hazel on the ground beside me, singing softly. Painted sisters dancing all around us, dust swirling up from bare feet. Cocky feathers catching firelight. Coloured skirts, circles and curves.

It was Young Man’s Time in Bluebush. Boys were being made into men. Here in the women’s camp, we were singing them goodbye.

The men were a couple of hundred yards to the west: a column of ghostly figures weaving in and out of a row of rattling branches. Clapsticks and boomerangs pounded the big bass rolling rhythm of the earth.

Gypsy Watson, our boss, the kirta, struck up another verse of the fire song: ‘Warlu wiraji, warluku…’

The rest of us tagged along behind.

My breasts, cross-hatched with ochre, moved gently as I turned and took a look around.

You couldn’t help but smile. The town mob: fractured and deracinated they might have been, torn apart by idleness and violence, by Hollywood and booze. But moments like these, when people came together, when they tried to recover the core, they gave you hope.

It was the songs that did it: the women didn’t so much sing them as pick them up like radio receivers. You could imagine those great song cycles rolling across country, taking their shape from what they encountered: scraps of language, minerals and dreams, a hawk’s flight, a feather’s fall, the flash of a meteorite. The resonance of that music is everywhere, even here, on the outskirts of the whitefeller town, out among the rubbish dumps and truck yards. It sings along the wires, it rings off bitumen and steel.

A disturbance—a slurred, drunken scream—somewhere to my right.

Maybe I spoke too soon.

Two women were yelling at each other. One was sitting down, obscured by the crowd. The other was all too visible: Rosie Brambles, looking like she’d just wandered out of the Drunks’ Camp.

Rambling Rosie, her dress a hectic red, her headscarf smeared with sweat and grease: she was built like a buffalo, with broad shoulders and spindly legs. She was drunk and angry. Nothing unusual in that; Rosie was mostly drunk and often angry, but this wasn’t the place for it.

Her antagonist was Cindy Mellow—mellow by name, far from it by nature—a manky-haired little spitfire from Curlew Creek. Sounded like their argument was about a bloke. Still nothing unusual. Rambling Rosie’s life was a succession of layabout lovers, black, white and every shade between. Cindy was being held back by her aunties, but they couldn’t hold her mouth: she cut loose with a string of insults, one of which was about a baby.

Rag to a bull, that. Years ago, one of Rosie’s babies had been found—alive, by chance—abandoned in a rubbish bin.

Rosie erupted: ‘Ah, you fuckin little bitch!’ She ran to a fire, grabbed a branch of burning lancewood, came back swinging.

Old ladies scattered, little kids screamed.

I jumped to my feet.

‘Rosie…’

She held the branch like a baseball bat, oblivious.

I moved closer, one arm extended.

‘Rosie!’ I raised my voice. ‘Settle down…’

She looked around. Gunpowder glare. No recognition. Then she rushed at me with a savage swing of the brand. I curved back and it swept past my head, sent a shower of sparks and a blast of heat into my face. I smelled my own hair, smoking.

I’d thought I was ready for her, a part of me was. But another part was mesmerised, staring with dazzled fascination at the river of light the torch left in its wake. In that shimmering arc I saw galaxies and golden fish, splinters and wings, crystal chips. I saw the song we’d just been singing.

‘Emily!’ Hazel’s warning scream.

I rolled out of the way as the fire swept past my head.

Enough was enough.

I snatched up a crowbar one of the old ladies had left behind. When Rosie came at me a third time I planted the crowie in the ground. The brand crashed into it with another explosion of sparks as I pivoted on the bar, slammed a thudding double-kick into her chest. She staggered backwards, hit the dirt. Suddenly still. Looked up, confused, winded, heaving.

Christ, Rosie. Don’t have a heart attack on me. My first day on the job and they’ll have me up on a murder charge.

Hazel came stomping over. ‘What you doing, Rosie? Running round fighting, putting the wind up these old ladies and little girls!'

Rosie raised herself onto an elbow, stared at the ground, shamefaced. Finished, the fight knocked out of her. The women began to make their way back to their places. But I glanced at Gypsy Watson, saw that she was troubled.

I knelt beside her, put a hand on her knee. ‘Don’t worry, Napurulla. It’s over now…’

She looked out over the dancing ground, her mouth at a downward angle. I followed her gaze. Rosie lurching off into the shadows. One of the teenage girls swaying under a set of headphones, travelling to the beat of a different drum. Cans of Coke, crucifixes and wristwatches, corrugated iron, powdered milk. In the distance the whitefeller lights of Bluebush cast an ugly orange pallor into the sky.

Gypsy was a Kantulyu woman, grown to adulthood in the desert out west. Hadn’t seen a whitefeller until she was in her twenties. Last year, one of her grandsons hanged himself in the town jail. A couple of months ago her brother Ted Jupurulla, one of the main men round here, died of cancer—a long, horrible death. She’d been in mourning ever since.

She was watching her world fall apart.

‘Over?’ she intoned wearily, shaking her head. ‘Yuwayi,’ she crackled, ‘but what over? They killin us with their machine dreams and poison. Kandiyi karlujana…’

The song is broken.

Which song? The one we’d just been singing, or the whole bloody opera? I gave her a hug, stood up, moved to the back of the crowd. The ceremony slowly resumed, other women took up the chant. But something was missing.

Somewhere among the hovels a rooster crowed. Didn’t necessarily mean the approach of dawn—that bird’s timing had been out of whack since it broke into Reggie Tapungati’s dope stash— but it was a reminder. Time to be on my way. McGillivray had said he wanted me there at first light.

I threw a scrap of turkey, a lump of roo-tail and an orange into my little saddlebag and headed for the track to town.

SCORCHER

I'D ONLY GONE a few yards when I became aware of bare feet padding up behind me.

Hazel, her upper body adorned with ochre, feathers in her hair, a friendly frown.

‘Sneakin off, Tempest?’

‘Didn’t want to disturb you.’

She grinned. ‘Disturb us? Heh! Even a tempest’d be peaceful after Rosie. You gotta go so early?’

‘Tom told me to be there first thing. Don’t want to give him or his mates the satisfaction of seeing me late for my first day at work. Especially the mates—’

She studied the distant town, a troubled expression on her face.

Somewhere out on Barker’s Boulevard a muscle car pitched and screamed: one of the apprentices from the mine. Apprentice idiot, from the sound of him. A drunken voice from the whitefeller houses bayed at the moon. A choir of dogs howled the response.

‘You sure you know what you’re doin? This…job?’ Her lips curled round the word like it had the pox.

‘Dunno that I ever know what I’m doing, Haze. I’ve said I’ll give it a go.’

She smiled, sympathetic. She knew my doubts better than I knew them myself; she’d been watching them play themselves out for long enough—since we were both kids on the Moonlight Downs cattle station, a couple of hundred k’s to the north-west. I’d flown the coop early, gone to uni, seen the world. Hazel had never left.

The little community there had hung on over the years, through the usual stresses endured by these marginal properties on the edge of the desert. It had held together, like some sort of ragged-arse dysfunctional family, thanks in large part to the influence of Hazel’s dad Lincoln Flinders and the efforts of Hazel herself.

Lincoln was dead now, savagely murdered not long ago. Just around the time I’d returned myself, come back from my restless travels and fruitless travails. Come home, hoping to find something, not knowing what.

I had a better idea now, though.

We’d taken the first tentative steps to independence: built a few rough houses, put in a water supply, planted an orchard. Our mate Bindi Watkins had started a cattle project, and was managing, in the main, to keep the staff from eating the capital. There was talk of a school, a store, a clinic.

The one thing we lacked was paid employment. So when Tom McGillivray, superintendent of the Bluebush Police and an old friend of the Tempest clan, came up with the offer of an Aboriginal Community Police Officer’s position we were happy to accept.

The only complication was the person he insisted on filling the position.

‘Join the cops, Emily!’ Hazel was still shocked.

‘Not real cops, Haze. ACPOs can only arrest people. I won’t be shooting anyone.’

‘Yeah but workin with them coppers…Old Tom, ’e’s okay—we know im long time. Trust im. But them other kurlupartu…’

I’d been wondering myself how McGillivray’s hairy-backed offsiders would react to a black woman in their midst.

‘Bugger em,’ I said with a bravado I wished I felt. ‘It’ll be an education.’

‘Yuwayi, but who for?’

‘It’s only a few weeks, Haze.’

That was the deal: a month in town, working alongside Bluebush’s finest, then I’d be based at Moonlight. I’d just come back from a short training course in Darwin in time to catch the tail end of the initiation rites.

The clincher in the deal—and this wasn’t just the cherry on top, it was the whole damn cake and most of the icing— was a big fat four-wheel-drive. Government owned, fuelled and maintained. The community was tonguing at the prospect; the goannas of Moonlight Downs wouldn’t know what hit em.

We paused at the perimeter of the town camp, looked back at the fire-laced ceremony. A chubby toddler broke free from the women, wobbled off in the direction of the men, his little backside bobbing. He hesitated, lost his nerve and rushed back into the comforting female huddle.

They all laughed. So did we, the sombre mood evaporating. Say what you like about me and my mob, there’s one thing you can’t deny: we’re survivors. You can kick us and kill us and drown us in bible and booze, but you better get used to us because we’re not going away.

‘So you’re out bush, first day?’

‘Tom got the call last night. Some old whitefeller killed at the Green Swamp Well Roadhouse.’

‘What happen?’

‘Dunno. Probably bashed to death with a cricket bat—deadly serious about their sport out there.’

Green Swamp Well’s main claim to fame—apart from the world’s biggest collection of beer coasters and mooning photos, its tough steaks and tougher coffee—was the annual Snowy Truscott Memorial Cricket Match.

Hazel glanced at the eastern sky. ‘Gonna be a scorcher.’

She was right: the drop of rain we’d had yesterday would only add to the humidity, and the radio predicted a brutal 45 degrees. Performing any sort of outdoor activity today would be like doing laps in a pressure cooker.

We were in the middle of the build-up. That time of year temperate Australia thinks of as spring: after the winter dry and not yet properly into the wet, when temperatures, tempers and the odd bullet go through the roof and the rain is always somewhere else. You’d be out of your mind if you didn’t go a little bit crazy.

‘Look after yourself,’ said Hazel. She kissed me on the cheek, returned to the dancing ground.

Recenzii

Praise for the Emily Tempest series:

"Beguiling first mystery . . . wonderful.”—The New York Times Book Review

“Startling turns of phrase, vivid Outback setting, and rich rendering of cultural differences. . . . All in all, the novel is a corker, engaging from page 1 and on through to an ending that pulls out all the stops.”—The Boston Globe

“A delightful, engaging book.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Perfect for mystery fans who are craving new horizons.”—Library Journal

“A hymn to the wit, courage, stark beauty and the power of dreaming of a unique people. One cannot help but be enriched by it.”—Anne Perry

"Beguiling first mystery . . . wonderful.”—The New York Times Book Review

“Startling turns of phrase, vivid Outback setting, and rich rendering of cultural differences. . . . All in all, the novel is a corker, engaging from page 1 and on through to an ending that pulls out all the stops.”—The Boston Globe

“A delightful, engaging book.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Perfect for mystery fans who are craving new horizons.”—Library Journal

“A hymn to the wit, courage, stark beauty and the power of dreaming of a unique people. One cannot help but be enriched by it.”—Anne Perry