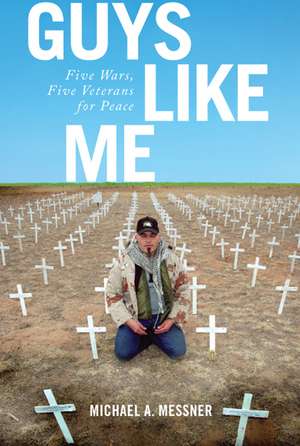

Guys Like Me: Five Wars, Five Veterans for Peace

Autor Professor Michael A. Messneren Limba Engleză Hardback – 17 dec 2018

Over the last few decades, as the United States has become embroiled in foreign war after foreign war, some of the most vocal activists for peace have been veterans. These veterans for peace come from all different races, classes, regions, and generations. What common motivations unite them and fuel their activism?

Guys Like Me introduces us to five ordinary men who have done extraordinary work as peace activists: World War II veteran Ernie Sanchez, Korean War veteran Woody Powell, Vietnam veteran Gregory Ross, Gulf War veteran Daniel Craig, and Operation Iraqi Freedom veteran Jonathan Hutto. Acclaimed sociologist Michael Messner offers rich profiles of each man, recounting what led him to join the armed forces, what he experienced when fighting overseas, and the guilt and trauma he experienced upon returning home. He reveals how the pain and horror of the battlefront motivated these onetime warriors to reconcile with former enemies, get involved as political activists, and help younger generations of soldiers.

Guys Like Me is an inspiring multigenerational saga of men who were physically or psychically wounded by war, but are committed to healing themselves and others, forging a path to justice, and replacing endless war with lasting peace

Guys Like Me introduces us to five ordinary men who have done extraordinary work as peace activists: World War II veteran Ernie Sanchez, Korean War veteran Woody Powell, Vietnam veteran Gregory Ross, Gulf War veteran Daniel Craig, and Operation Iraqi Freedom veteran Jonathan Hutto. Acclaimed sociologist Michael Messner offers rich profiles of each man, recounting what led him to join the armed forces, what he experienced when fighting overseas, and the guilt and trauma he experienced upon returning home. He reveals how the pain and horror of the battlefront motivated these onetime warriors to reconcile with former enemies, get involved as political activists, and help younger generations of soldiers.

Guys Like Me is an inspiring multigenerational saga of men who were physically or psychically wounded by war, but are committed to healing themselves and others, forging a path to justice, and replacing endless war with lasting peace

Preț: 232.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 348

Preț estimativ în valută:

44.43€ • 47.51$ • 37.05£

44.43€ • 47.51$ • 37.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Livrare express 12-18 martie pentru 32.54 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781978802810

ISBN-10: 1978802811

Pagini: 292

Ilustrații: 29 B&W images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Ediția:None

Editura: Rutgers University Press

Colecția Rutgers University Press

ISBN-10: 1978802811

Pagini: 292

Ilustrații: 29 B&W images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Ediția:None

Editura: Rutgers University Press

Colecția Rutgers University Press

Notă biografică

MICHAEL A. MESSNER is a professor of sociology and gender studies at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He is the author or editor of many books, including Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women, King of the Wild Suburb: A Memoir of Fathers, Sons and Guns, and No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport and the Unevenness of Social Change (Rutgers University Press).

Extras

Chapter 1

Projects of Peace

If I step outside the door of my home in South Pasadena at just the right time on New Year’s Day, I stand a chance of witnessing the tail end of a B-2 Stealth Bomber’s flyover of the nearby Rose Bowl. A neighbor who viewed this spectacle gushed to me that the low-flying bomber was “just the coolest thing ever.” I agreed that seeing the bat-like stealth bomber so close up was awe-inspiring, but wondered aloud why we need to start a football game by celebrating a $2 billion machine that has dropped bombs on Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. When I suggested that the flyover, to me, was yet another troubling instance of the militarization of everyday life, my neighbor replied that, well, perhaps it was thanks to such sophisticated war machines that we are now enjoying a long period of peace. I reminded him that we are still fighting a war in Afghanistan, that we have troops still in Iraq, and that even this past fall, four US special forces soldiers died in battle in Niger. It may feel like peace to many of us at home, but for US troops, and for people on the receiving end of US bombs, drone missile strikes, and extended ground occupations, it must feel like permanent war.

War Is Both Everywhere and Nowhere

The fact that my neighbor and I talked past one another should come as no surprise. For most Americans today, war is both everywhere and nowhere. On the one hand, it seems omnipresent. Politicians continually raise fears among the citizenry, insisting that we pony up huge proportions of our nation’s financial and human capital to fight a borderless and apparently endless “Global War on Terror.” We’re inundated with war imagery—an unending stream of films and TV shows depicting past and current wars,[i] pageantry like the Rose Bowl flyover, and celebrations of the military in sports programming, exploiting sports to recruit the next generation of soldiers.[ii] The result, according to social scientist Adam Rugg, is “a diffused military presence” in everyday life.[iii]

Following the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, US wars in the Middle East have continued to rage, spilling over national borders and introducing new and troubling questions about modern warfare. Though scaled back since the initial invasions, these wars continue. Through fiscal year 2018, the financial cost of our “Post-9/11 Wars” has surpassed $1.8 trillion, and Brown University’s Costs of War Project puts that number at $5.6 trillion, taking into account interest on borrowed money to pay for these wars and estimates of “future obligations” in caring for medical needs of veterans.[iv] The human toll has been even costlier. By 2018, 6,860 US military personnel had been killed in the Global War on Terror, and more than 52,000 had been wounded.[v] Most of these have been young men. Through the end of 2014, 391,759 military veterans had been treated in Veterans Administration (VA) facilities for “potential or provisional Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)” following their return from Afghanistan or Iraq.[vi] It’s difficult to accurately measure the carnage inflicted on the populations of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, but the Costs of War Project estimates that between 2001 and 2018 more than 109,000 “opposition fighters” and over 200,000 civilians have been directly killed, and 800,000 more “have died as an indirect result of the wars.”[vii]

Military conscription was halted in the US in 1973, a direct legacy of the mass movement that helped to end the War in Vietnam. With no draft in place, the military shifted to an all-volunteer force that required intensifying recruitment strategies, especially in times of escalating wars. During the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, the volunteer military faced dire personnel shortages that led to multiple redeployments, placing huge burdens on military personnel and their families.[viii] Two years into the Iraq War, US military desertions were on the rise, and “…recruiters were consistently failing to meet monthly enlistment quotas, despite deep penetration into high schools, sponsorship of NASCAR and other sporting events, and a $3-billion Pentagon recruitment budget.”[ix] In response, the military stepped up recruitment ads on TV and in movie theatres, and launched direct recruitment efforts in American high schools and community colleges.[x] The American high school, faced with increased recruiting efforts and opposition from parents and others, became, in education scholar William Ayers’ words, “a battlefield for hearts and minds.”[xi]

Since 9/11, the military seems omnipresent and a state of war permanent, while paradoxically, the vast majority of Americans feel untouched by it all. Disconnected from the wars, we go about our daily lives as though we’re living in a period of extended peace. For most of us, war is nowhere. How is this Orwellian situation tolerable, or even possible? Following America’s defeat in Vietnam, the government has engaged in a carefully controlled, public relations framing of news of all wars and invasions,[xii] containing contrary views that could emerge from critical investigative reporting. Examples include “embedding” reporters with US troops during the invasion of Iraq and prohibiting the news media from filming or photographing flag-draped coffins as they’re unloaded from military transport planes.

Another reason most people experience these omnipresent wars as “nowhere” lies in the shifting nature of warfare. Today, the military can deploy new technologies to minimize the number of US casualties while maximizing the carnage of those designated as terrorists, enemies, or targets. The normalization of drone strikes—escalated by President Obama and expanded by President Trump—is the epitome of this “out of sight, out of mind” warfare. As the US deploys drone strikes, “…war becomes “unilateral…a kind of permanent, low-level military action that threatens to erase the boundary between war and peace and…makes it easier for the United States to engage in casualty-free, and therefore debate-free, intervention while further militarizing the relationship between the US and the Muslim world,” according to anthropologist Hugh Gusterson.[xiii]

Another reason for the electorate’s distance from current wars is the vast divide between civilians and the military. Only ½ of 1 percent of the population is in the military, the lowest rate since between the world wars. LA Timesreporters David Zucchino and David Cloud also note that Congress today has the lowest rate of military service in history, and four successive presidents have never served on active duty. [xiv] As many as 80 percent of those in the military come from families in which a parent or a sibling is also in the military. Military personnel often live behind the gates of installations or in surrounding communities. This segregation is so pronounced that nearly half of the 1.3 million active-duty service members in the US are concentrated in five states: California, Virginia, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia. In short, Zucchino and Cloud conclude, the US military is becoming a separate and isolated warrior class. With no draft in place, large proportions of the population, especially those from the privileged classes, are increasingly insulated from the experience and realities of military service and war.

Veterans are symbolically made visible through “Support the Troops” celebrations and political oratory, but the voices of actual veterans who have fought our wars are mostly under the radar. And even less audible are the voices of vets who advocate for peace. I wrote this book because I believe it’s more important than ever for us to listen to the voices of veterans for peace, those who have been there and recovered sufficiently (no easy task) to inform us how traumatically devastating and morally compromising it is to be an instrument of America’s military-industrial geopolitics. This book highlights the life stories of five veterans whose experiences spanned five wars: World War II, the Korean War, the War in Vietnam, the Gulf War, and the recent and continuing wars in the Middle East. Why is this legacy of peace advocacy by military veterans so little-known?

Manly Silence

Part of the reason many Americans do not know the true costs of war, I believe, is due to a phenomenon I’ve come to call “manly silence,” like my grandfather’s reluctance to talk about his World War I experiences or about his opposition to future wars. Every war gives birth a new generation of veterans who live out their lives with the trauma of combat embedded their bodies and minds, but many remain silent about their experiences. That was certainly my father’s modus operandus after World War II, and even my grandfather’s predominant way of dealing with his experiences in World War I.

How do we understand so many men’s silence about what they endured, especially the millions of combatants of the two world wars, but continuing with combat veterans today? Although women fight shoulder to shoulder with men today, and perhaps this phenomenon will slowly change, the military is still a place governed by rigid and narrow conceptions of masculinity, a key aspect of which is keeping a stiff upper lip.

One common refrain among war veterans is that it makes no sense to talk of such things because only someone who was there can truly understand their experience. Only veterans who endured the same traumas, witnessed similar horrors, or committed comparable acts of brutality are worth opening to. Otherwise silence, often accompanied by self-medication and other efforts at dissociating oneself from these traumas, prevails.

The foundation for this kind of emotional fortification rests on narrow definitions of masculinity, often internalized at an early age and then enforced and celebrated in masculinist institutions like the military. But rigid masculinity is not confined to the military; it’s more general. Research by psychologist Joseph Schwab and his colleagues showed that men routinely respond to stressful life experiences by avoiding emotional disclosure that they fear might make them appear vulnerable.[xv] Silence, the researchers concluded, is the logical outcome of internalized rules of masculinity: a real man is admired and rewarded for staying strong and stoic during times of adversity.

Who benefits from this manly silence? Certainly institutions like the military that train and then rely on men’s private endurance of pain, fear, and trauma. But individual men (and women) rarely benefit from such taciturnity. Trying to live up to this narrow ideal of masculinity comes with severe costs for men’s physical health, emotional well-being, and relationships.[xvi] Researchers and medical practitioners have compiled long lists of the costs men pay for adhering to narrow definitions of masculinity: undiagnosed depression;[xvii] alcoholism, heart disease, and risk-taking that translate into shorter lifespans;[xviii] fear of emotional self-disclosure and suppressed access to empathy, resulting in barriers to intimacy.[xix]

A 2015 study of 1.3 million veterans who served during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars showed suicide rates twice that of non-veterans.[xx] The New York Times reported in 2009 escalating rates of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and homicide committed by men who had returned from multiple deployments to the war in Iraq.[xxi] PTSD impedes—often severely, and sometimes for the rest of one’s life—veterans’ re-entry into civilian life, their development of healthy, productive, and happy postwar and post-military lives. A combat veteran of the Vietnam War told me, “PTSD? It don’t ever go away.” For the men I interviewed, PTSD was a lifelong challenge that—following in some cases years of denial, struggle, alcoholism, and medical care—eventually served as an impetus to do something healthy, positive, and peaceful with their lives.

During World War I, military leaders and medical experts were concerned with the growing problem of “shell shock” among troops subjected to the horrors of trench warfare. Little understood at the time was the emotional impact of modern warfare’s growing efficiency—with machine guns, volleys of artillery fire, or strafing from low-flying planes—in maiming and massacring hundreds, even thousands in a very short time. Leo Braudy argues that by World War I, technological war had “obliterated” the ways wars traditionally elevated and celebrated a chivalrous ideal of heroic warrior masculinity. Eclipsed by the realities of modern warfare in the first decades of the twentieth century, these outmoded ideals were still widely held, including the belief that “war…would affirm national vitality and individual honor…and rescue the nation from moral decay.”[xxii]

The belief that fighting a war would build manly citizens plagued men’s already terrible experiences on the battlefield. Grunts like my grandfather experienced no glorious affirmation of their manhood; they were exposed instead to terror, vulnerability, and disillusion. For many, this experience of modern warfare manifested as a suite of crippling somatic symptoms that came to be called “shell shock,” viewed at the time, as described by George L. Mosse, as a kind of “enfeebled manhood.”

Shattered nerves and lack of will-power were the enemies of settled society and because men so afflicted were thought to be effeminate, they endangered the clear distinction between genders which was generally regarded as an essential cement of society…The shock of war could only cripple those who were of a weak disposition, fearful and, above all, weak of will…War was the supreme test of manliness, and those who were the victims of shell-shock had failed this test.[xxiii]

During World War II, as the US lost an estimated 504,000 troops, attitudes began to shift. General Eisenhower expressed dismay with General Patton’s denigration and abuse of soldiers suffering from “battle neurosis” as malingering cowards. Mosse explains that in 1943, General Omar Bradley issued an order “…that breakdown in combat be regarded as exhaustion, which helped to put to rest the idea that only those men who were mentally weak, ‘the unmanly men,’ collapsed under stress in combat.”[xxiv] Re-labeling such breakdowns as “combat fatigue” shifted blame away from individuals and began to shed light on the conditions that created the symptoms.

During the Vietnam War, the cluster of physical and emotional symptoms brought on by the trauma of war was given a medical label: Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, or PTSD. A 2003 study by the National Center for PTSD concluded that twenty to twenty-five years after the end of the war, “a large majority of Vietnam Veterans struggled with chronic PTSD symptoms, with four out of five reporting recent symptoms.”[xxv] The most common symptoms the study pointed to were alcohol abuse and dependence, generalized anxiety disorder, and anti-social personality disorder. Vietnam vets who had served “in war zones suffered at much higher levels than Vietnam-era vets who didn’t. What caused these high rates of PTSD? A common view is that the sustained levels of fear that men in battle normally experience create lasting psychological fears that impact one for years, perhaps the rest of one’s life. Others point to physical wounds as causing PTSD.

Moral Injury

In his riveting book On Killing, Dave Grossman surveys research on PTSD to argue that the most powerful cause of the disorder is the guilt, shame, and denial that follow the “burden of killing” other human beings in war. Grossman points out that a fundamental problem of military leaders throughout history has involved training and motivating soldiers to overcome “…a simple demonstrable fact that there is within most men an intense resistance to killing their fellow man. A resistance so strong that, in many circumstances, soldiers on the battlefield will die before they can overcome it.”[xxvi]During World War II, Grossman points out, military leaders were dismayed by their troops’ frequent “failure to fire”: 80 to 85 percent of riflemen “did not fire their weapon at an exposed enemy.” Many who did fire missed their targets purposefully. Military trainers in future wars transformed training regimes in ways that dramatically increased the “fire rate.” In Vietnam, US soldiers with an opportunity to fire their weapon at an enemy soldier did so 95 percent of the time. If, as Grossman argues, knowledge of killing one or more other human beings contributes the most potent psychological fuel for PTSD, it should come as no surprise the huge numbers of veterans who came home from the Vietnam War suffering from symptoms of PTSD. Absent the group absolution that returnees from previous wars received from victory parades and other postwar celebrations, Vietnam veterans more often experienced their guilt as a private, individual burden.

This focus on the internalized shame one carries from having killed others had led professionals who work with veterans to focus their interventions on what they began to call “moral injury.” Clinical psychologist Brett Litz and his colleagues argue that the broad symptom profile of PTSD results from internalized fear reaction to threat; moral injury, on the other hand, results from negative emotions about oneself, one’s own character, grounded in shame, remorse, and self-condemnation over what one has done to others.[xxvii] Moral injury results when one’s self-image as a good person is undermined by the knowledge of having killed other people, when one’s moral compass has been irredeemably transgressed. Several of the men I interviewed expressed this kind of shame and remorse—both for individual acts they committed and for the shared collective responsibility for killing enemy soldiers and civilians in what they came to believe were unjust wars.

Moral injuries have plagued recent veterans who have returned from the wars in the Middle East. Modern technological warfare often increases the distance between the killer and the killed, thus theoretically lessening the shame the killer might feel. But Hugh Gusterson, in his fascinating analysis of drone warfare, observes that an Air Force pilot sitting in a trailer in Nevada, directing a drone strike at a distant target in the Middle East is separated geographically from his or her target by thousands of miles. However, Gusterson argues, unlike the bomber pilot who never sees his target close-up, the drone pilot is required to engage in an extended, magnified surveillance of the target site, creating a kind of “intimacy” with those on the ground. And following a drone missile strike, the pilot must again carefully surveil the now-smoking site to be sure the intended target is dead (and to order a second strike if not). In this “after” view, the pilot will also witness the civilian bystanders—the “collateral damage”—who were also killed or maimed by the strike. Gusterson asserts that the shame that drone pilots experience from their distant kills is a form of moral injury.[xxviii] The powerful 2016 documentary film National Bird focuses on the experiences of a handful of former drone operators, illuminating the deep moral injuries they carry and also on the ways that, as veterans, they became whistleblowers and antiwar activists.

Gender and Peace

Some war veterans break through the limits of stoic masculinity, alcoholism, drug abuse, and destructive silences to become vocal advocates for peace. How does a man accomplish this pivot from forgetting to remembering, from crippling constraint to positive action, from being a cog in a massive war machine to taking on a project of history-making through peace advocacy? For one thing, a shift toward peace advocacy involves adopting a critical, oppositional political perspective. A study by social scientist David Flores revealed that the narratives of Iraq War vets-turned peace activists were “conversion stories” of political resistance to the stories they had been told about the reasons for the US invasion of Iraq. In my interviews, I also heard politically resistant narratives. Also fundamental to most of these men’s transformations to peace advocacy were the ways they faced the moral and therapeutic challenge of coming to grips with deeply embodied emotional trauma, including guilt, shame, and fear.

A second foundational aspect of taking on a life project as an advocate for peace involves confronting previously learned, widely accepted, and celebrated definitions of masculinity. In focusing this book on war and men, I understand that I risk rendering invisible women’s experiences of war and the military. As the feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe has shown, the militarization of everyday life in the US and throughout the world has dire consequences for civilian women’s lives. Women also have a long history of serving in the military—traditionally as nurses and medics, and increasingly today in the center of combat zones. And women have been and continue to be a driving force in US and international peace movements.[xxix]

Though they are a numerical minority in organizations like Veterans for Peace and Iraq Veterans Against the War, women veterans are assuming increasingly visible leadership roles in these organizations and in public debates about gender and war. Consider, for instance, the two women former drone operators-turned activists who are featured in American Bird, and the brave women veterans who appear in The Invisible War, the powerful 2012 documentary that illuminates widespread sexual harassment and sexual assault in the military. I interviewed Army veteran and IVAW member Wendy Barranco, who fended off sexual harassment and assault while serving in a combat zone in Iraq.Barranco, who had moved at age four from Mexico to Los Angeles with her mother, recalls how Army recruiters “roamed the halls” of her LA high school in 2003 as the United States was ramping up its war in Iraq. “I mean they were everywhere.” The teenaged Barranco had to fight off a drunken sexual advance from her married and considerably older recruiter. Still, she decided to enlist, and part of the reason, she recalls, “was patriotism for September 11, after it happened,” and her desire “to give something back to this country that gave my family and I so much.”

Trained as a medic, Barranco found herself deployed in 2005 to Iraq where the nineteen-year-old Private spent nine months working in the hospital operating room in the hot combat zone of Tikrit. Barranco found “a sense of purpose and personal fulfillment” in the O.R., saving lives of wounded US soldiers and local Iraqis, occasionally while wearing “a flack vest” to protect against “incoming mortar rounds.” She learned soon that dealing with such “heavy trauma” meant that her “feelings were going to have to be put aside. The moment that you let fear or sadness or anything like that in, your job becomes compromised. I put it away.”

However, Barranco had not counted on having to fend off continual sexual harassment from the lead doctor in the OR. For “the entire fucking nine months,” she recalled, “I not only had to do my job, but I had to watch my own back with this guy. That’s an added layer of I’m already in a fucking war zone. I’m already having to do my job. Now I have to deal with your ass too, and I can’t do anything about it. It’s not—it is not fun.” Nor had Barranco expected to have to scratch, wrestle, and knee in the groin a colleague who attempted to rape her in her sleeping quarters. A woman Sergeant who knew of the assault told Barranco to “keep my mouth shut. Keep my head down. Don’t do anything. Don’t cause trouble for the unit.”

Following Barranco’s return to civilian life in the summer of 2006, the trauma she had “compartmentalized” while in Iraq “started really coming out. I felt used by the military. I felt like a rag that had just been used to clean up a mess and just discarded.” Barranco discovered the fledgling IVAW, soon assuming a leadership role in the Los Angeles chapter and helping to organize counter-recruitment education and antiwar forums. She related her story of sexual harassment in a high-profile national IVAW event, Winter Soldier Iraq and Afghanistan, and her account was included in a 2008 book.[xxx] Wendy Barranco’s activism illustrates how the growing role of younger women in veterans’ peace organizations steers these organizations to meld peace activism with feminist actions to confront issues like sexual harassment, sexual assault, and domestic violence that disproportionately impact women military personnel, veterans, and their families.[xxxi]

As always, when gender becomes more visible in an organization—in this case, through women’s activism within the ranks and as veterans—we are invited to ask new and critical questions about men’s experiences. This book tells a story of five men—“guys like me”—who fought in wars and became advocates for peace. It is a story that, like much of my previous work, asks questions about men and masculinity that would not have occurred to me had it not been for the influences of feminist scholarship and women’s activism. Since men, masculinity, and militarism are so often seen to be in close (and mythically heroic) correspondence, the war-veteran-as-peace-advocate may be viewed as an oxymoron. This is precisely what interests me. The veterans for peace I interviewed experienced political and moral awakenings, to be sure. But their ability to translate these political and moral commitments into public advocacy for peace was predicated on a fundamental shift in each man’s understanding and embodiment of what it means to be a man.[xxxii]

None of the men who appear in this book experienced what I would call a feminist transformation, though Gregory Ross, veteran of the American War in Vietnam, did join a pro-feminist men’s anti-violence group in the late 1970s. But their stories reveal how in joining the military and deploying to war, each had been sold a “manhood package” that was intended to make non-reflexive warriors of them, and that ultimately proved to be self-destructive. The parameters of this manhood package are likely to be especially alluring to very young men who, when they first deploy to war zones, are barely old enough to drink alcohol legally; are still immersed in cultural images of male heroism in warfare from film, TV, and video games; and have had limited experience with sex. Deployed to wars in distant locales, these young men learn quickly that there is little room for elevated conceptions of individual heroism in war. But they also learn that when on leave—in places like Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Korea—the fear and loathing they experience in war zones can be temporarily numbed through ready access to commodified recreation in the form of booze and women sex workers. With several decades to reflect on this, Korean War vet Woody Powell referred to inexpensive sex with local prostitutes as part of the spoils of being “part of a conquering army.”

An important element of the transformations the five men profiled in this book experienced involves rejecting the manhood package they were sold as young men. This means accepting, talking about, and sharing one’s emotional vulnerabilities with others. It means, in many cases, learning to respect women as colleagues and allies in collective efforts for justice. It means rejecting pop culture military heroes and finding flesh-and-blood heroes, women and men in one’s own life, who have inspired their commitments to progressive activism. It also means coming to grips with one’s own memory of war and with the ways we as a society remember and misremember our wars.

Contesting the Industry of Memory

On a scorching July day, I stood on the street corner with a handful of Santa Fe Veterans for Peace at their weekly vigil, wearing my green VFP T-shirt, the back of which is emblazoned with an antiwar quote from Dwight David Eisenhower, the World War II Army General who became the thirty-fourth President of the United States:

I HATE WAR

as only a soldier who has lived it can,

as only one who has seen its brutality,

its futility, its stupidity.

I stood next to a combat veteran of the War in Vietnam who pointed his VFP banner toward passing cars as he quipped about my shirt, “Do you think maybe Eisenhower said that while he was crushing veterans at Anacostia?” He was referring to Eisenhower’s role, along with other future World War II heroes Douglas MacArthur and George Patton, in violently suppressing the “Bonus Army” of more than 20,000 US World War I veterans who descended on Washington, DC. during the nadir of the Great Depression to demand the bonuses they’d been promised. During the spring and summer of 1932, much of the Bonus Army camped on Anacostia Flats across the Potomac River from the Capitol. When President Hoover ordered the Army to evict them, troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, his aide Major Dwight Eisenhower, and George Patton attacked with tear gas and set Bonus Army huts on fire. In the words of historian Howard Zinn, “The whole encampment was ablaze.” Two veterans were shot to death, a baby died, an eight-year-old boy was blinded, and “a thousand veterans were injured by gas.”[xxxiii]

My fellow protestor’s sally about the Eisenhower quote on my T-shirt was more than a sarcastic one-liner that called into question the depth of the former General’s antiwar commitments. It was emblematic of the way activist members of Veterans for Peace pride themselves in being students of history. Knowing history is a key component of peace activism, as antiwar veterans’ groups continually find themselves responding to the government’s purposeful revisionism that distorts what actually happened to create ideological framings that justify current and future wars. Collective memory of wars, in other words, is a contested terrain of stories, symbols. and meanings upon which antiwar veterans insist on speaking their truth. For antiwar veterans, this is a continuous up-hill battle.

History, it’s often said, is written by the victors. This truism normally points to the reality that following wars, the nation that emerges victorious has the power to impose its version of the “truth” as to who caused the war, who should be punished for atrocities or war crimes, who should pay reparations, and who should be honored as heroes. But consider this question: Who, following a war, gets to impose their “truth” not simply between nations formerly at war, but also within a nation? Most often, it is powerful political leaders, aligned with the nation’s economic elite and supported by the owners of mass media, whose version of history gets adopted as official truth, becomes required reading in textbooks, and crystallizes as national mythology. In Nothing Ever Dies, Viet Thahn Nguyen argues that a powerful “memory industry” inundates citizens with official versions of the truth about past wars. “By far the most powerful of its kind, the American industry of memory is on par with the American arms industry.”[xxxiv] The military itself is part of this industry of memory. Top military brass—who after all not only survived past wars, but were also promoted up the ranks and commended for their wartime service—become purveyors of the official truth, as they induct, train, and lead the next generations of soldiers into the next wars.

In his People’s History of the US, Howard Zinn offers dozens of counter-stories that challenge the official versions of history. It takes tremendous effort and chutzpa to assert these or any unsanctioned versions of history. My grandfather’s frustrated outburst on a long-past Veterans Day was a moment of private resistance against what he saw as the official hijacking of Armistice Day. General Smedley Butler’s antiwar rants in the 1930s challenged the official story on the causes and consequences of World War I, reframing it as a story of collusion of heads of state to send American boys off to slaughter in support of wealthy industrialists’ greed.[xxxv]

The meaning of the Vietnam War continues to be fiercely contested. As I was writing this book, activists in Veterans for Peace were organizing on several fronts to challenge the communal memory of this war, as several fifty-year anniversaries of major events in the war approached.[xxxvi] Veterans organized to support Vietnamese efforts to rebuild the My Lai memorial at the site of the infamous 1968 massacre.[xxxvii] For months, I tracked the dialogues of Veterans in anticipation of how they would respond to Ken Burns documentary on the war in Vietnam. Members of the VFP “Vietnam Full Disclosure” group expressed dismay that Burns adopted a neutral view of the war, promoting a narrative of false equivalences: that all sides entered into the war with good intentions, all made mistakes, and the war was tragic for everyone concerned.[xxxviii] These veterans—many had been active in the GI resistance during that war, later joining veterans’ antiwar organizations—saw it not as an unfortunate “mistake” made by well-meaning people, but as a normal manifestation of US foreign policy that deploys military power to impose “US interests” in far reaches of the world, and that it was launched and justified on a foundation of lies from US leaders. In Hell No!, written shortly before his death in 2017, antiwar activist Tom Hayden added his voice to this battle of memory to “put a stop to false and sanitized history” of the war. “We need to resist the military occupation of our minds,” he wrote. “The war makers seek to win on the battlefield of memory what they lost in the battlefields of war.”[xxxix]

When the US withdrew from Vietnam in 1973, more than 58,000 US soldiers were dead and in excess of 3,000,000 Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian soldiers and civilians are estimated to have been killed during the conflict. In the United States, a vibrant and sometimes militant antiwar movement had succeeded in helping end the war. But the battle to frame the meanings of the war had begun long before. President Nixon, Vice President Agnew, and their political allies had worked to drive a strategic wedge between the rapidly growing antiwar movement and the so-called “silent majority” of Americans upon whom Nixon relied for pro-war support. A key prong in Nixon’s strategy was to charge that antiwar protesters were engaging in unpatriotic acts that disrespected and endangered the troops in the field. The increasingly visible role played by GI war resisters and returning war veterans within the antiwar movement, as we’ll see in chapter 4 through the story of Gregory Ross, made the Nixon Administration’s story an increasingly tough sell with the general public.

By the time the war ended, the impact of years of disastrous carnage, the well-documented revelations that the government had lied about both the reasons for and the execution of the war,[xl] and the political and cultural changes instigated by the antiwar movement combined to dramatically shift public opinion toward a skeptical, even oppositional stance toward government claims about the necessity of new military interventions abroad. The public adopted a cautious, non-interventionist view: The War in Vietnam, it was widely believed, was ill-advised, and perhaps it was a mistake to think the US could continue to be the world’s policeman. And many held more critical views, seeing the American War in Vietnam not so much as a “mistake,” but rather, as revealing the ugly side of the normal values and practices of US foreign policy: an assumption that our military can and should control the destinies of distant nations through brute force and violence; the reality that the US military, rather than being a force for democracy abroad, was a tool of imperial domination.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, these non-interventionist and critical views of US foreign policy were being hotly contested. President Ronald Reagan bemoaned Americans’ reluctance to support foreign interventions as resulting from what he dubbed “the Vietnam Syndrome,” a crippling national timidity that translated into weakness and vulnerability. Reagan contributed to a largely successful effort to reframe the story of the Vietnam War, blaming the US defeat not on bad policy, but on the ways that the antiwar movement and weak-willed politicians forced the military to fight “with one hand tied behind its back.” A key part of this reframing involved disseminating a story that became a widely accepted myth: that returning Vietnam veterans were routinely spat upon by antiwar protesters. In his book The Spitting Image, sociologist (and Vietnam War veteran) Jerry Lembke traces the rise of the story of the spat-upon veteran as “the grounding image for a larger narrative of betrayal [that] told a story of how those who were disloyal to the nation’s interests ‘sold out’ or ‘stabbed in the back’ our military.”[xli] His research with veterans and his analysis of mass media coverage concluded that the image of the spat-upon veteran had little if any basis in fact. Rather, most actual incidents he uncovered of veterans being verbally abused, egged, and publicly insulted were stories of antiwar veterans being attacked by pro-war demonstrators; Lembke had experienced this form of abuse himself. Indeed, a 1975 study found that 75 percent of Vietnam War veterans were opposed to the war,[xlii] organizations like Vietnam Veterans Against the War had been for years a highly visible force in massive public antiwar demonstrations,[xliii] and media-savvy veterans staged powerfully symbolic events like the April 1971 discarding of war medals and ribbons by more than 800 Vietnam veterans on the steps of the US Capitol building.[xliv]

However, Lembke shows, as a widely accepted “perfecting myth”[xlv] the image of the spat-upon Vietnam Veteran helped to radically reconfigure the collective memory of the Vietnam War. It was not just politicians who promulgated this story. Hollywood played a key role as well. Nineteen-seventies’ films like Coming Home and Tracks,according to Lembke, “created an American mindset receptive to suggestions that veterans were actually spat upon.”[xlvi]By the 1980s, popular culture seemed fully on board with the goal of countering the “post-Vietnam” mistreatment of Vietnam veterans and the peace movement’s supposed feminization of America. Hollywood urged American men to muscle up through popular 1980s’ films like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s The Terminator (1984) and Commando (1985), and Sylvester Stallone’s three (1982, 1985, 1988) films celebrating the heroic exploits of Vietnam War veteran John Rambo, who returns to Vietnam with a vengeance, muscles flexing and guns blazing, to rescue US prisoners of war who had been forgotten and left to die by weak-kneed bureaucrats at home.

Rambo, Commando, the Terminator, and other rock-hard, men-as-weapon, men-as-machine images filled the nation’s screens in the 1980s, a cultural moment that media studies scholar Susan Jeffords called a “remasculinization of America,” when the idea of real men as decisive, strong and courageous arose from the confusion and humiliation of the US defeat in Vietnam and against the challenges of feminism and gay liberation.[xlvii] The major common theme in these films was the Vietnam veteran (and POW/MIA) as abandoned and victimized by his own government, American protestors, and the women's movement—all of which are portrayed as feminizing forces that shamed and humiliated American men. Two factors were central to the symbolic remasculinization that followed: First, these film heroes of the 1980s were rugged individuals, who stoically and rigidly stood up against the bureaucrats who were undermining American power and pride with their indecision and softness. Second, hard, muscular male bodies accessorized with massive weapons, were the major symbolic expression of this remasculinization. These men wasted few words; instead speaking through explosive and decisively violent actions.

Jeffords argues that the male body-as-weapon serves as the ultimate spectacle and locus of masculine regeneration in post-Vietnam era films of the 1980s. There is a common moment in many of these films: The male hero is seemingly destroyed in an explosion of flames, and as his enemies laugh, he miraculously rises (in slow motion) from under water, firing his weapon and destroying the enemy. Drawing from Klaus Theweleit's analysis of the "soldier-men" of Nazi Germany,[xlviii] Jeffords argues that this moment symbolizes a "purification through fire and rebirth through immersion in water."[xlix] In this historical moment, the Terminator’s most famous sentence, “I’ll be back,” perhaps best articulated this remasculinized American man: “back” from the cultural feminization of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and “back” from the national humiliation of the lost war in Vietnam.

Following Ronald Reagan, subsequent US Presidents built support for and defused dissent against new US military interventions by exploiting the myth of the abused Vietnam veteran, and promoting a remasculinized image of America. During the 1990-1991 Operation Desert Storm—popularly known as the Gulf War—President George H. W. Bush defused possible dissent and mobilized support for the war in two ways. First, media access to coverage of the war was far more controlled and restricted by the Pentagon, compared with reporters’ more open access to the war in Vietnam. And second, the Bush administration carefully orchestrated a “support the troops” campaign at home, invoking the supposedly shameful way that Vietnam veterans had been treated, and by promoting “Operation Yellow Ribbon,” a visible campaign to build symbolic support at home for the troops in the field. Lembke recounts that when some parents objected to what they saw as the propagandistic goals of “Operation Eagle,” the campaign to build support for the troops in public schools, “…the press and grassroots conservatives construed their objections as anti-soldier.”[l] In equating any antiwar sentiment with anti-troops sentiment, the government had succeeded in framing its war effort in a way that defused antiwar mobilizations. Over a decade later his son would renew his father’s war against Iraq—with disastrous results—but for the moment President George H. W. Bush concluded his 1991 speech to the American Legislative Council on a note of triumph for a remasculinized America: “It’s a proud day for America. And, by God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam Syndrome once and for all.”[li]

Battles over the interpretations of past wars are not just academic. The stakes over whose “truth” will prevail are high: what we believe to be true of past wars powerfully influences whether we’ll support, express skepticism, or actively oppose efforts to wage current and future wars. Winning public acceptance of the American War in Vietnam continues to be foundational to strategies developed by neoconservatives attempting to muster public support for US interventions in the Middle East, just as collective amnesia about the early-1950s Korean War contributes to public confusion about the saber-rattling between President Donald Trump and North Korea. At the same time, counter-narratives of the America War in Vietnam have been crucial to antiwar movements’ ongoing resistance to current and future wars. The words we use to describe the past matter. Today, members of Veterans for Peace insist on adopting the name used by the people of Vietnam for this war, “the American War in Vietnam.”

Although it’s a recent and still ongoing war, the meanings of the Iraq War are also highly contested. Leaders that drew us into this war like former Vice President Dick Cheney still stubbornly claim that the war was right and good, while a central tenet of the conventional frame for the Iraq War was that it was a “mistake,” based on false information. Many Democratic Party leaders who voted in favor of the US invasion of Iraq (including then-Senator Hillary Clinton) now chide the second Bush Administration for having misled the nation and Congress, thrusting the US into a years-long disastrous war that has cost billions of dollars, wasted many lives, while yielding no discernable gains, either for the people of Iraq or for the long-term security of the United States (although it seems the fossil fuel industry has profited). “If only we had known” that Iraq actually had no weapons of mass destruction, many of these leaders now lament. But many people did know in advance, including UN weapons inspectors, and 12 million people worldwide who demonstrated in opposition to the invasion.

Now, in the collective memory, the Iraq War is commonly seen as an unfortunate “mistake” rather than as a routine operation of American foreign policy. “All wars are fought twice,” Viet Thanh Nguyen asserts, “the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”[lii] The effort to frame the collective memory of past wars is an ongoing battle. There is the industry of memory attempting to impose its official storyline, and there are veterans grappling with the trauma, guilt, fear, pain, and anguish embedded in their bodies and minds.

Memory, Bodies, and Identities

The veterans I interviewed for this book viewed their public opposition to war as an act of moral necessity and patriotism. They also viewed it as a necessity for healing; for many of these men, public antiwar activism is coupled with deeply personal efforts to heal their own emotional wounds, sustain sobriety, help other veterans, and engage in community activism to stop interpersonal violence and address poverty and homelessness. Veterans’ peace advocacy is often coupled with therapeutic healing, and with social justice activism in the community and in the world. It is at once an effort to heal the self, to connect with others in peaceful ways, and to say yes to peace in the world.

As I spoke with these men, I became fascinated with the question of how their past experiences with war and their current commitments to peace and healing have become salient aspects of their identities. I’ve come to understand individual identity not through a layered “onion” image that imagines a core self, fixed during infancy and childhood, continuing throughout life to assert conscious and unconscious influence on a person, even as more life experiences are layered upon the core. Rather, I’ve come to understand identity as a never completed, always developing tapestry. As a person ages, experiences the ups and downs of interpersonal relationships, moves through a historically shifting array of institutions (families, schools, mass media, military, twelve-step programs, social movement organizations, churches, workplaces), new fabrics are sewn in and the tapestry of one’s identity shifts its shape and textures. Previous experiences don’t disappear; they remain as threads that are woven and re-woven into the tapestry, seeming to disappear at times, later reemerging and attaining new meaning.

Extending this image, I see a man’s wartime experience as a thread in the larger, always-growing tapestry of his life. Like all threads, it can be woven and rewoven, shifting in importance, salience, and meaning as he moves in and out of different contexts, as his sense of self in the world shifts and his values change or ossify. But the wartime thread is extraordinary, often among the most salient of threads in a man’s life, even if, as when I interviewed World War II veteran Ernie Sanchez, it constitutes less than 2 percent of the entire tapestry of his life. Nor is the wartime thread made of soft cloth that easily blends in; rather, it is more akin to a copper wire, shining at times, tarnishing with time, but always carrying the possibility—all it takes is the right precipitating event—to trigger visceral bodily reactions grounded in past trauma. We will see this in Ernie Sanchez’s story of PTSD triggered a half-century after World War II; in Korean War veteran Woody Powell’s awakening to action, facilitated by his newfound sobriety and sparked by the US invasion of Iraq; and in Vietnam veteran Gregory Ross’s description of his automatic recoiling, still today, when he hears crashing noises that conjure his embodied memory of the 24/7 booming of Navy artillery.

What became fascinating to me in talking with these men were the ways that deeply embedded memories of wartime trauma were, in some cases, “forgotten” for long periods of time. In The Warriors, the most profound book I’ve read on the psychology, emotions, and ethics of combat, philosopher and World War II veteran Glenn J. Gray wrote, “The effort to assimilate those intense war memories to the rest of my experience is difficult and even frightening. Why attempt it? Why not continue to forget? … I am afraid to forget. I fear that human creatures do not forget cleanly, as animals presumably do. What protrudes and does not fit in our pasts rises to haunt us and make us spiritually unwell in the present.”[liii] Indeed, some of the men I interviewed appear at times in their lives to have achieved some tentative life-stability in “forgetting” their wartime experience, but they would likely agree with Gray that they ultimately could “… not forget cleanly, [that] what protrudes and does not fit in our pasts rises to haunt us and make us spiritually unwell in the present.”

As I learned more about the experience of war, the workings of memory, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), and moral injury, a veteran’s ambivalence about remembering or forgetting became less puzzling to me. What I began to wonder about is how, and under what conditions men consciously seek to transcend or to mobilize their wartime trauma? Once foregrounded, what do they do with memories of war? For the men I studied, how did the threads of memories of physical pain, fear, guilt, or shame, once ignited, get rewoven into efforts to heal the self and others, to advocate daily for peace, and to engage in collective action for social justice? A veteran’s moment of engagement with a conscious life project of peace and justice advocacy begins to take shape when he seizes this thread, and commences a conscious—and often a painful and difficult—reweaving, often against the grain.

I have come to see that in making a public claim of peace advocacy and in connecting with others politically as peace activists, these veterans are enacting what existentialist philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir called a “project of freedom.”[liv] At first glance, asserting a language of human freedom to describe these men’s experiences may seem questionable. It seems common sense to understand a soldier in a combat situation existing in a situation where “freedom,” is almost nonexistent. Indeed, I listened to stories of men drafted into the military, thrust into dangerous, frightening, and appalling situations not of their choosing, positioned in the lower rungs of chains of command that ordered them what to do and when to do it, and confronted with situations that one can only hope to survive, not to control. Few situations in life—incarceration, perhaps—seem more the antithesis of freedom than war. But for the existentialists, freedom is not defined as unfettered choice and action. Put another way, human freedom is not preventedby the existence of limits and constraints—what Sartre called “facticity” and de Beauvoir called “contingency”—instead, it is only, in Sartre’s words, an individual’s “going beyond a situation” pushing against constraining facticity and contingencies, through which a person can assert a project of individual freedom. This “going beyond,” for Sartre, is not simply a negation of a given situation one may find intolerable; it is simultaneously a positive, forward-looking project that “…opens onto the ‘nonexistent,’ to what has not yet been.”[lv] As I witness a small group of Veterans for Peace struggling to keep their antiwar banners aloft on a gusty street corner as hundreds of cars drive past, left and right, most of the drivers paying no apparent attention to war and peace issues, these activists’ collective project is illuminated for me by Sartre’s description of human freedom. Through their actions they are “…transcending the given” of a world of violence, war, and injustice, and they are also imagining and acting together to move the world “toward the field of possibles.”[lvi]

How does a veteran get to this point of joining with others to attempt to transcend the given and push toward a different “field of possibles”? Following his wartime experience, a veteran may feel his range of possible choices and actions expanding—or at least the moment-to-moment constraints around him becoming less evident than they were during combat. But the situation of the war veteran is likely still to be one of difficult—emotional, health, relational, financial—contingencies. The conscious forging of an existential project involves seeing beyond the limits of current contingencies, and acting to create a different future. The stories I tell in subsequent chapters illuminate four intertwining themes, expressed in different ways by each individual veteran.

Self healing. The men I interviewed confronted their own moral injury or PTSD variously, through individual and group therapy, through spiritual healing practices like meditation, acupuncture or yoga, through twelve-step recovery programs, or through creative writing.

Service to others. Some of vets I interviewed found their way into helping professions—working with homeless people, serving veterans in recovery, providing health or community support for the poor.

Political activism. All of the men I interviewed engaged in peace advocacy, engaging individuals in their everyday lives about war and peace issues, often wearing Veterans for Peace buttons or clothing to create conversations. Most of these men also engaged with VFP and other veterans’ organizations, building coalitions to work for peace and justice and to contest the industry of memory.

Reconciliation. Reflecting the observation of Viet Thanh Nguyen that in remembering past wars, Americans too often “remember our own” dead, but fail to remember our fallen enemies or civilian casualties as full human beings, veterans for peace insist on talking about former enemies, including people they killed, as fully human, and some of veterans engage in organized transnational projects to build human connections with former “enemies.

I have found the life history interview to be an ideal way to understand individual lives as “projects,” at once constrained by war and other violent and unjust social processes, while also expressing transcendent creativity, stubborn political resistance, and hopeful ideals of freedom. I spent many hours, in multiple sittings, collecting the life histories of the veterans who are featured in this book. To be sure, such a small number of life history interviews cannot illuminate what developmental psychologist Daniel Levinson described as predictable stages of development in the “seasons of a man’s life.”[lvii] Instead, as sociologist Raewyn Connell has shown, a “theorized life history” offers a window into individual agency and the social processes of embodiment and memory. Life history studies, Connell emphasizes, are useful not only for uncovering psychological dynamics, or even simply for understanding how the social world constrains actions; they also illuminate how individuals’ choices and actions in turn shape the world. In Connell’s words, a life history interview reveals “the making of social life through time. It is literally history.”[lviii]

In Guys Like Me, I draw from life history interviews with five men who fought in five wars to better understand these men’s lives from the inside, and to illuminate recent and contemporary history. Each chapter foregrounds the voice of one man, supplemented with my own secondary research, to illuminate the personal experience of war and its aftermath, and to better understand the ways in which individuals take on a project of peace advocacy. In chapter 2 we meet World War II Army combat Veteran Ernie Sanchez, who confronted his wartime deeds fifty years after his war, following a traumatic bout with PTSD. Chapter 3 tells the story of Wilson “Woody” Powell, an Air Force veteran of the Korean War who eventually became an activist and leader in Veterans for Peace. Vietnam Naval Veteran and Veterans for Peace member Gregory Ross is the focus in chapter 4. Chapter 5 chronicles the experiences of Daniel Craig, an Army veteran of Operation Desert Storm, better known as the Gulf War. Chapter 6 centers on the life of Navy veteran Jonathan Hutto, an Iraq War veteran active in Veterans for Peace.

There is a necessary intimacy in getting inside one man’s life story. But rather than viewing the five stories in this book as discrete tales of separate individuals and separate wars, I seek to show the ways in which these men’s biographies, and their wars, are overlapping and interconnected parts of an ongoing social history.[lix] These men’s actions as peace advocates too are interconnected. When individual projects of healing, service to others, reconciliation with former enemies, and peace activism are joined in an organization like Veterans for Peace, the result is a collective project of veterans and allies aiming to make history.

“The effort to assimilate those intense war memories to the rest of my experience is difficult and even frightening. Why attempt it? Why not continue to forget? I fear that human creatures do not forget cleanly, as animals presumably do. What protrudes and does not fit in our pasts rises to haunt us and make us spiritually unwell in the present.”

--J. Glenn Gray, The Warriors, 1959

Projects of Peace

If I step outside the door of my home in South Pasadena at just the right time on New Year’s Day, I stand a chance of witnessing the tail end of a B-2 Stealth Bomber’s flyover of the nearby Rose Bowl. A neighbor who viewed this spectacle gushed to me that the low-flying bomber was “just the coolest thing ever.” I agreed that seeing the bat-like stealth bomber so close up was awe-inspiring, but wondered aloud why we need to start a football game by celebrating a $2 billion machine that has dropped bombs on Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. When I suggested that the flyover, to me, was yet another troubling instance of the militarization of everyday life, my neighbor replied that, well, perhaps it was thanks to such sophisticated war machines that we are now enjoying a long period of peace. I reminded him that we are still fighting a war in Afghanistan, that we have troops still in Iraq, and that even this past fall, four US special forces soldiers died in battle in Niger. It may feel like peace to many of us at home, but for US troops, and for people on the receiving end of US bombs, drone missile strikes, and extended ground occupations, it must feel like permanent war.

War Is Both Everywhere and Nowhere

The fact that my neighbor and I talked past one another should come as no surprise. For most Americans today, war is both everywhere and nowhere. On the one hand, it seems omnipresent. Politicians continually raise fears among the citizenry, insisting that we pony up huge proportions of our nation’s financial and human capital to fight a borderless and apparently endless “Global War on Terror.” We’re inundated with war imagery—an unending stream of films and TV shows depicting past and current wars,[i] pageantry like the Rose Bowl flyover, and celebrations of the military in sports programming, exploiting sports to recruit the next generation of soldiers.[ii] The result, according to social scientist Adam Rugg, is “a diffused military presence” in everyday life.[iii]

Following the American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, US wars in the Middle East have continued to rage, spilling over national borders and introducing new and troubling questions about modern warfare. Though scaled back since the initial invasions, these wars continue. Through fiscal year 2018, the financial cost of our “Post-9/11 Wars” has surpassed $1.8 trillion, and Brown University’s Costs of War Project puts that number at $5.6 trillion, taking into account interest on borrowed money to pay for these wars and estimates of “future obligations” in caring for medical needs of veterans.[iv] The human toll has been even costlier. By 2018, 6,860 US military personnel had been killed in the Global War on Terror, and more than 52,000 had been wounded.[v] Most of these have been young men. Through the end of 2014, 391,759 military veterans had been treated in Veterans Administration (VA) facilities for “potential or provisional Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)” following their return from Afghanistan or Iraq.[vi] It’s difficult to accurately measure the carnage inflicted on the populations of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, but the Costs of War Project estimates that between 2001 and 2018 more than 109,000 “opposition fighters” and over 200,000 civilians have been directly killed, and 800,000 more “have died as an indirect result of the wars.”[vii]

Military conscription was halted in the US in 1973, a direct legacy of the mass movement that helped to end the War in Vietnam. With no draft in place, the military shifted to an all-volunteer force that required intensifying recruitment strategies, especially in times of escalating wars. During the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, the volunteer military faced dire personnel shortages that led to multiple redeployments, placing huge burdens on military personnel and their families.[viii] Two years into the Iraq War, US military desertions were on the rise, and “…recruiters were consistently failing to meet monthly enlistment quotas, despite deep penetration into high schools, sponsorship of NASCAR and other sporting events, and a $3-billion Pentagon recruitment budget.”[ix] In response, the military stepped up recruitment ads on TV and in movie theatres, and launched direct recruitment efforts in American high schools and community colleges.[x] The American high school, faced with increased recruiting efforts and opposition from parents and others, became, in education scholar William Ayers’ words, “a battlefield for hearts and minds.”[xi]

Since 9/11, the military seems omnipresent and a state of war permanent, while paradoxically, the vast majority of Americans feel untouched by it all. Disconnected from the wars, we go about our daily lives as though we’re living in a period of extended peace. For most of us, war is nowhere. How is this Orwellian situation tolerable, or even possible? Following America’s defeat in Vietnam, the government has engaged in a carefully controlled, public relations framing of news of all wars and invasions,[xii] containing contrary views that could emerge from critical investigative reporting. Examples include “embedding” reporters with US troops during the invasion of Iraq and prohibiting the news media from filming or photographing flag-draped coffins as they’re unloaded from military transport planes.

Another reason most people experience these omnipresent wars as “nowhere” lies in the shifting nature of warfare. Today, the military can deploy new technologies to minimize the number of US casualties while maximizing the carnage of those designated as terrorists, enemies, or targets. The normalization of drone strikes—escalated by President Obama and expanded by President Trump—is the epitome of this “out of sight, out of mind” warfare. As the US deploys drone strikes, “…war becomes “unilateral…a kind of permanent, low-level military action that threatens to erase the boundary between war and peace and…makes it easier for the United States to engage in casualty-free, and therefore debate-free, intervention while further militarizing the relationship between the US and the Muslim world,” according to anthropologist Hugh Gusterson.[xiii]

Another reason for the electorate’s distance from current wars is the vast divide between civilians and the military. Only ½ of 1 percent of the population is in the military, the lowest rate since between the world wars. LA Timesreporters David Zucchino and David Cloud also note that Congress today has the lowest rate of military service in history, and four successive presidents have never served on active duty. [xiv] As many as 80 percent of those in the military come from families in which a parent or a sibling is also in the military. Military personnel often live behind the gates of installations or in surrounding communities. This segregation is so pronounced that nearly half of the 1.3 million active-duty service members in the US are concentrated in five states: California, Virginia, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia. In short, Zucchino and Cloud conclude, the US military is becoming a separate and isolated warrior class. With no draft in place, large proportions of the population, especially those from the privileged classes, are increasingly insulated from the experience and realities of military service and war.

Veterans are symbolically made visible through “Support the Troops” celebrations and political oratory, but the voices of actual veterans who have fought our wars are mostly under the radar. And even less audible are the voices of vets who advocate for peace. I wrote this book because I believe it’s more important than ever for us to listen to the voices of veterans for peace, those who have been there and recovered sufficiently (no easy task) to inform us how traumatically devastating and morally compromising it is to be an instrument of America’s military-industrial geopolitics. This book highlights the life stories of five veterans whose experiences spanned five wars: World War II, the Korean War, the War in Vietnam, the Gulf War, and the recent and continuing wars in the Middle East. Why is this legacy of peace advocacy by military veterans so little-known?

Manly Silence

Part of the reason many Americans do not know the true costs of war, I believe, is due to a phenomenon I’ve come to call “manly silence,” like my grandfather’s reluctance to talk about his World War I experiences or about his opposition to future wars. Every war gives birth a new generation of veterans who live out their lives with the trauma of combat embedded their bodies and minds, but many remain silent about their experiences. That was certainly my father’s modus operandus after World War II, and even my grandfather’s predominant way of dealing with his experiences in World War I.

How do we understand so many men’s silence about what they endured, especially the millions of combatants of the two world wars, but continuing with combat veterans today? Although women fight shoulder to shoulder with men today, and perhaps this phenomenon will slowly change, the military is still a place governed by rigid and narrow conceptions of masculinity, a key aspect of which is keeping a stiff upper lip.

One common refrain among war veterans is that it makes no sense to talk of such things because only someone who was there can truly understand their experience. Only veterans who endured the same traumas, witnessed similar horrors, or committed comparable acts of brutality are worth opening to. Otherwise silence, often accompanied by self-medication and other efforts at dissociating oneself from these traumas, prevails.

The foundation for this kind of emotional fortification rests on narrow definitions of masculinity, often internalized at an early age and then enforced and celebrated in masculinist institutions like the military. But rigid masculinity is not confined to the military; it’s more general. Research by psychologist Joseph Schwab and his colleagues showed that men routinely respond to stressful life experiences by avoiding emotional disclosure that they fear might make them appear vulnerable.[xv] Silence, the researchers concluded, is the logical outcome of internalized rules of masculinity: a real man is admired and rewarded for staying strong and stoic during times of adversity.

Who benefits from this manly silence? Certainly institutions like the military that train and then rely on men’s private endurance of pain, fear, and trauma. But individual men (and women) rarely benefit from such taciturnity. Trying to live up to this narrow ideal of masculinity comes with severe costs for men’s physical health, emotional well-being, and relationships.[xvi] Researchers and medical practitioners have compiled long lists of the costs men pay for adhering to narrow definitions of masculinity: undiagnosed depression;[xvii] alcoholism, heart disease, and risk-taking that translate into shorter lifespans;[xviii] fear of emotional self-disclosure and suppressed access to empathy, resulting in barriers to intimacy.[xix]

A 2015 study of 1.3 million veterans who served during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars showed suicide rates twice that of non-veterans.[xx] The New York Times reported in 2009 escalating rates of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and homicide committed by men who had returned from multiple deployments to the war in Iraq.[xxi] PTSD impedes—often severely, and sometimes for the rest of one’s life—veterans’ re-entry into civilian life, their development of healthy, productive, and happy postwar and post-military lives. A combat veteran of the Vietnam War told me, “PTSD? It don’t ever go away.” For the men I interviewed, PTSD was a lifelong challenge that—following in some cases years of denial, struggle, alcoholism, and medical care—eventually served as an impetus to do something healthy, positive, and peaceful with their lives.

During World War I, military leaders and medical experts were concerned with the growing problem of “shell shock” among troops subjected to the horrors of trench warfare. Little understood at the time was the emotional impact of modern warfare’s growing efficiency—with machine guns, volleys of artillery fire, or strafing from low-flying planes—in maiming and massacring hundreds, even thousands in a very short time. Leo Braudy argues that by World War I, technological war had “obliterated” the ways wars traditionally elevated and celebrated a chivalrous ideal of heroic warrior masculinity. Eclipsed by the realities of modern warfare in the first decades of the twentieth century, these outmoded ideals were still widely held, including the belief that “war…would affirm national vitality and individual honor…and rescue the nation from moral decay.”[xxii]

The belief that fighting a war would build manly citizens plagued men’s already terrible experiences on the battlefield. Grunts like my grandfather experienced no glorious affirmation of their manhood; they were exposed instead to terror, vulnerability, and disillusion. For many, this experience of modern warfare manifested as a suite of crippling somatic symptoms that came to be called “shell shock,” viewed at the time, as described by George L. Mosse, as a kind of “enfeebled manhood.”

Shattered nerves and lack of will-power were the enemies of settled society and because men so afflicted were thought to be effeminate, they endangered the clear distinction between genders which was generally regarded as an essential cement of society…The shock of war could only cripple those who were of a weak disposition, fearful and, above all, weak of will…War was the supreme test of manliness, and those who were the victims of shell-shock had failed this test.[xxiii]

During World War II, as the US lost an estimated 504,000 troops, attitudes began to shift. General Eisenhower expressed dismay with General Patton’s denigration and abuse of soldiers suffering from “battle neurosis” as malingering cowards. Mosse explains that in 1943, General Omar Bradley issued an order “…that breakdown in combat be regarded as exhaustion, which helped to put to rest the idea that only those men who were mentally weak, ‘the unmanly men,’ collapsed under stress in combat.”[xxiv] Re-labeling such breakdowns as “combat fatigue” shifted blame away from individuals and began to shed light on the conditions that created the symptoms.

During the Vietnam War, the cluster of physical and emotional symptoms brought on by the trauma of war was given a medical label: Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, or PTSD. A 2003 study by the National Center for PTSD concluded that twenty to twenty-five years after the end of the war, “a large majority of Vietnam Veterans struggled with chronic PTSD symptoms, with four out of five reporting recent symptoms.”[xxv] The most common symptoms the study pointed to were alcohol abuse and dependence, generalized anxiety disorder, and anti-social personality disorder. Vietnam vets who had served “in war zones suffered at much higher levels than Vietnam-era vets who didn’t. What caused these high rates of PTSD? A common view is that the sustained levels of fear that men in battle normally experience create lasting psychological fears that impact one for years, perhaps the rest of one’s life. Others point to physical wounds as causing PTSD.

Moral Injury

In his riveting book On Killing, Dave Grossman surveys research on PTSD to argue that the most powerful cause of the disorder is the guilt, shame, and denial that follow the “burden of killing” other human beings in war. Grossman points out that a fundamental problem of military leaders throughout history has involved training and motivating soldiers to overcome “…a simple demonstrable fact that there is within most men an intense resistance to killing their fellow man. A resistance so strong that, in many circumstances, soldiers on the battlefield will die before they can overcome it.”[xxvi]During World War II, Grossman points out, military leaders were dismayed by their troops’ frequent “failure to fire”: 80 to 85 percent of riflemen “did not fire their weapon at an exposed enemy.” Many who did fire missed their targets purposefully. Military trainers in future wars transformed training regimes in ways that dramatically increased the “fire rate.” In Vietnam, US soldiers with an opportunity to fire their weapon at an enemy soldier did so 95 percent of the time. If, as Grossman argues, knowledge of killing one or more other human beings contributes the most potent psychological fuel for PTSD, it should come as no surprise the huge numbers of veterans who came home from the Vietnam War suffering from symptoms of PTSD. Absent the group absolution that returnees from previous wars received from victory parades and other postwar celebrations, Vietnam veterans more often experienced their guilt as a private, individual burden.