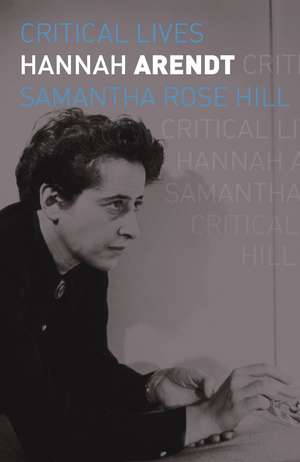

Hannah Arendt: Critical Lives

Autor Samantha Rose Hillen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 oct 2021

Din seria Critical Lives

-

Preț: 81.37 lei

Preț: 81.37 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei - 5%

Preț: 79.31 lei

Preț: 79.31 lei -

Preț: 84.23 lei

Preț: 84.23 lei -

Preț: 82.98 lei

Preț: 82.98 lei -

Preț: 83.16 lei

Preț: 83.16 lei -

Preț: 82.01 lei

Preț: 82.01 lei - 13%

Preț: 83.98 lei

Preț: 83.98 lei -

Preț: 83.48 lei

Preț: 83.48 lei -

Preț: 82.64 lei

Preț: 82.64 lei -

Preț: 82.64 lei

Preț: 82.64 lei -

Preț: 83.44 lei

Preț: 83.44 lei -

Preț: 81.74 lei

Preț: 81.74 lei -

Preț: 82.01 lei

Preț: 82.01 lei -

Preț: 140.04 lei

Preț: 140.04 lei -

Preț: 83.44 lei

Preț: 83.44 lei -

Preț: 83.81 lei

Preț: 83.81 lei -

Preț: 83.38 lei

Preț: 83.38 lei -

Preț: 84.20 lei

Preț: 84.20 lei -

Preț: 82.01 lei

Preț: 82.01 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 82.64 lei

Preț: 82.64 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 82.54 lei

Preț: 82.54 lei -

Preț: 82.64 lei

Preț: 82.64 lei -

Preț: 82.54 lei

Preț: 82.54 lei - 6%

Preț: 131.57 lei

Preț: 131.57 lei -

Preț: 79.07 lei

Preț: 79.07 lei -

Preț: 119.81 lei

Preț: 119.81 lei -

Preț: 137.83 lei

Preț: 137.83 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 81.55 lei

Preț: 81.55 lei -

Preț: 82.89 lei

Preț: 82.89 lei -

Preț: 81.38 lei

Preț: 81.38 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 83.27 lei

Preț: 83.27 lei -

Preț: 139.57 lei

Preț: 139.57 lei -

Preț: 83.07 lei

Preț: 83.07 lei -

Preț: 85.74 lei

Preț: 85.74 lei -

Preț: 82.54 lei

Preț: 82.54 lei -

Preț: 81.74 lei

Preț: 81.74 lei -

Preț: 83.70 lei

Preț: 83.70 lei -

Preț: 83.34 lei

Preț: 83.34 lei -

Preț: 82.64 lei

Preț: 82.64 lei -

Preț: 83.95 lei

Preț: 83.95 lei -

Preț: 83.44 lei

Preț: 83.44 lei

Preț: 83.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 125

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.97€ • 16.67$ • 13.21£

15.97€ • 16.67$ • 13.21£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Livrare express 01-07 martie pentru 24.95 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781789143799

ISBN-10: 1789143799

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: 30 halftones

Dimensiuni: 127 x 197 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: REAKTION BOOKS

Colecția Reaktion Books

Seria Critical Lives

ISBN-10: 1789143799

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: 30 halftones

Dimensiuni: 127 x 197 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: REAKTION BOOKS

Colecția Reaktion Books

Seria Critical Lives

Notă biografică

Samantha Rose Hill is a senior fellow at the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities and associate faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Aeon, LitHub, OpenDemocracy, Public Seminar, Contemporary Political Theory, and Theory and Event. For more information, visit samantharosehill.com.

Extras

In many ways Hannah Arendt’s work is about thinking. In her Denktagebuch (thinking journals) she asks: ‘Gibt es ein Denken das nicht Tyrannisches ist?’ (Is there a way of thinking that is not tyrannical?) At the beginning of The Human Condition, she posits: ‘What I propose, therefore, is very simple: it is nothing more than to think what we are doing. When she covered the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem for the New Yorker, she found Eichmann lacked the capacity to engage in self-reflective thinking, to imagine the world from the perspective of another. Arendt’s final work, The Life of the Mind, begins with a treatise on ‘Thinking’.

In many respects Arendt became a writer by accident. She said she wrote to remember what she thought, to record what was worth remembering, and that writing was an integral part of the process of understanding. This is evidenced throughout her journals and published work, where she engaged in what she called ‘thinking exercises’. In her preface to Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought, she wrote ‘thought itself arises out of incidents of living experience and must remain bound to them as the only guidepost by which to take its bearings.’ For Arendt, thinking exercises were a way to engage in the work of understanding, and they were a way to break free from her education in the tradition of German philosophy.

For Arendt, the work of thinking and understanding requires solitude. She drew a sharp distinction between the four walls of the private realm and the public space of appearances. And from an early age, there was a tension between her appetite for solitude and her desire for recognition. Even the reading of a book, she reflected, requires some degree of isolation. In order to engage in the activity of thinking, one must retreat from the harsh light of the public in order to experience the silent dialogue of thought. Arendt called this dialogue the ‘two-in-one’: the conversation one has with one’s self.

In recent years, many people have turned to the work of Hannah Arendt to try to understand the political crises faced today – the decline of liberal democracy, the spread of fake news, the rise of the social sphere, the triumph of technology, the loss of the private realm and the experience of mass loneliness, to name a few. What is it about Arendt’s writing that resonates with so many today? Why do we keep turning to her to understand the political conditions of the twenty-first century? Arendt’s work has now become a part of our inheritance, something that we can look to in order to help us in the work of understanding, but she would have protested the use of her work today as an analogy for our present political crises. In an interview shortly before her death, she said, ‘To look to the past in order to find analogies by which to solve our present problems is, in my opinion, a mythological error.’

Arendt’s passion for understanding and hunger for life are just as important as her ability to engage in self-reflective critical thinking. I do not think the two can be untied, because one must really love the world in order to care for it as deeply as she did. In the darkest hour of her life, when she was in an internment camp with no sense of the future, contemplating suicide, she decided that she loved life too much to give it up. She decided to live and found laughter in doing so. I hope that her courage in the face of such dark times inspires us to have the courage we need to fight the darkness we face today in this ‘none too beautiful world of ours.

In many respects Arendt became a writer by accident. She said she wrote to remember what she thought, to record what was worth remembering, and that writing was an integral part of the process of understanding. This is evidenced throughout her journals and published work, where she engaged in what she called ‘thinking exercises’. In her preface to Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought, she wrote ‘thought itself arises out of incidents of living experience and must remain bound to them as the only guidepost by which to take its bearings.’ For Arendt, thinking exercises were a way to engage in the work of understanding, and they were a way to break free from her education in the tradition of German philosophy.

For Arendt, the work of thinking and understanding requires solitude. She drew a sharp distinction between the four walls of the private realm and the public space of appearances. And from an early age, there was a tension between her appetite for solitude and her desire for recognition. Even the reading of a book, she reflected, requires some degree of isolation. In order to engage in the activity of thinking, one must retreat from the harsh light of the public in order to experience the silent dialogue of thought. Arendt called this dialogue the ‘two-in-one’: the conversation one has with one’s self.

In recent years, many people have turned to the work of Hannah Arendt to try to understand the political crises faced today – the decline of liberal democracy, the spread of fake news, the rise of the social sphere, the triumph of technology, the loss of the private realm and the experience of mass loneliness, to name a few. What is it about Arendt’s writing that resonates with so many today? Why do we keep turning to her to understand the political conditions of the twenty-first century? Arendt’s work has now become a part of our inheritance, something that we can look to in order to help us in the work of understanding, but she would have protested the use of her work today as an analogy for our present political crises. In an interview shortly before her death, she said, ‘To look to the past in order to find analogies by which to solve our present problems is, in my opinion, a mythological error.’

Arendt’s passion for understanding and hunger for life are just as important as her ability to engage in self-reflective critical thinking. I do not think the two can be untied, because one must really love the world in order to care for it as deeply as she did. In the darkest hour of her life, when she was in an internment camp with no sense of the future, contemplating suicide, she decided that she loved life too much to give it up. She decided to live and found laughter in doing so. I hope that her courage in the face of such dark times inspires us to have the courage we need to fight the darkness we face today in this ‘none too beautiful world of ours.

Recenzii

"Hill notes that working on Augustine led Arendt to one of her central concepts—love of the world, or amor mundi. She quotes Arendt: 'It is through love of the world that man explicitly makes himself at home in the world.' . . . For Arendt . . . the world is not the space in which we forget our being-unto-death while pursuing trivial affairs; rather, it is a space that we share with others, with whom we build the lasting institutions of public life. Being-in-the-world involves being in the company of others with whom we enjoy talking and interacting. We labor to meet the needs of the body, create art and artifacts, and engage in moral and political activities."

"Hill repositions Arendt as a feminist heroine, 'demanding, unapologetic and opinionated,' ever ready to confront male dominance in a discipline that she came to reject: Midway though her American academic career she began describing herself as a political writer rather than a philosopher."

"Hill quickly cuts to the core of Arendt’s principal talent: the formulation of trenchant categories and definitions that, for all their certitude, take from the past only what is necessary, looking otherwise to the present and future. . . . Hill spares us the clichéd, tabloid-ish critiques that make up a sizable chunk of Arendtian lore. . . . Instead, she calmly—and quietly, but without truckling—applies her close readings of Arendt’s most controversial ideas to our own oftentimes taut and illiberal social atmosphere."

"While the aim of this biography might be to serve as a brief, lively introduction to Arendt, Hill accomplishes something richer. In introducing us to Arendt’s life and thought, what emerges is an example of thinking as a dynamic activity. . . . Hill says that Arendt’s gift to us is the call to 'think the world anew.' While thinking is a solitary activity, it also has relational dimensions. If friends can be traveling companions, so too can some thinkers who came before us, thinkers who continue to provoke us. Hill does not present Arendt as a banister to hold up our thinking. Rather, she aptly shows that Arendt is someone to read now because Arendt is someone worth thinking with."

"This slim, accessible book walks the reader through Arendt’s life while introducing her major works and ideas. . . . Most intellectual biographies emphasize ideas over personal details, which is generally the correct approach. But Arendt is different. Her work, as Hill repeatedly shows, was influenced by the events of her life."

"Hill’s intellectual biography of Hannah Arendt is a timely look at one of the most impactful, if elusive, twentieth-century political thinkers. . . . Hill’s Arendt is a thinker who moves easily from poetry to philosophy, from reflections on politics to an analysis of thinking itself. . . . Hill writes lucidly about the key ideas and is particularly good on Arendt’s deep and lasting friendships. Arendt inspired love and loyalty among those close to her, and while her commitment always to 'stop and think' led to sharp disagreements, it also resulted in meaningful, enduring relationships."

"In Hannah Arendt, Hill explains that Arendt was more interested in the process of thought—of reconciling ourselves to the world so that we can properly deal with it—than in articulating transcendent truths (which, according to her, did not exist). Along the way, Hill illuminates a warmer, more personal side of Arendt than we’ve seen in op-eds and think pieces over the past few years. It’s an image that complicates the idea of Arendt as an unsentimental thinker. . ."

“This book is brilliant. . . . Hill . . . must know as much as anyone about Hannah Arendt. She’s dived into Arendt’s surviving papers, notebooks, and even poetry, spending many hours in the archive. She knows every little bit of paper that Hannah Arendt scribbled on. And what’s so great about this as a biography is that Hill has done something that biographers rarely do—she’s been highly selective in what she’s included. . . . We have the benefit of a highly intelligent writer, selecting what she feels to be most important to bring out about Arendt. . . . Here we have a very elegant story about Arendt’s life that brings out key moments and the most important themes in her thought.”

"As Hill points out in Hannah Arendt, even in works such as The Origins of Totalitarianism—surprise bestseller of the Trump era—the political is invariably brought back to the personal."

"Hill recovers what is perhaps Arendt's main message for our time: the importance of learning to think for ourselves from our experiences in a shared world."

"In light of the potential pitfalls in reading Arendt’s work, Hill’s biography provides a vital service' . . . Each chapter provides a lucid introduction to the key points of each work. For those interested in Arendt’s work—and anyone curious about political ideas should be—Hill’s work is an excellent primer."

"Blending biographical detail, sharp commentary, and personal correspondence, Hill’s focused and fast-paced book contextualizes Arendt’s major works by exploring the experiences which shaped the contours of her thought, engaging with a figure who continues to be widely read and debated as a guide to understanding contemporary political conditions."

"Hannah Arendt offers an extraordinarily readable 210 pages, combining sharp analysis with concise and precise summary of Arendt’s life and works. Twelve of the twenty chapters are named for individual article or book publications by Arendt, and the other eight are: Inner Awakening, Turn Towards Politics, Internment, State of Emergency, Transition, Friendship, Reconciliation, and Storytelling. Hill wields such a thorough knowledge of available details, quotations, and sources regarding Arendt that she chooses the most engaging, thought-provoking ones and integrates them into her prose. . . . Her biography blends sophisticated philosophy, productive historical context, and ‘Easter eggs’ of human-interest story."

"Perhaps more than anything, Hill’s biography is indeed an intimate portrayal of Arendt. . . and its relatively short length makes it more accessible to readers."

"Hill’s book is an informative and coherent narrative of Arendt’s life and key ideas. . . . As a brief biography, Hill’s book does its job admirably."

“Hannah Arendt by Samantha Rose Hill could hardly appear more opportunely. Arendt's way of thinking, though quick to the point of being difficult to follow, appeals to an increasing number of men and women who question the meaning of their lives in the world we share. Arendt's own writings and the books and essays analyzing them may seem exhaustive, yet Hill's work does something new: Without simplifying Arendt's thinking, she opens it to contemporary readers who, in the darkness of our times, will find a friend, a woman, who lived through the darkest of all times. It becomes clear to the reader that among Arendt's gifts to the world was the welcome she gave to those distinct from herself as passengers aboard her bullet-trains of thought. “