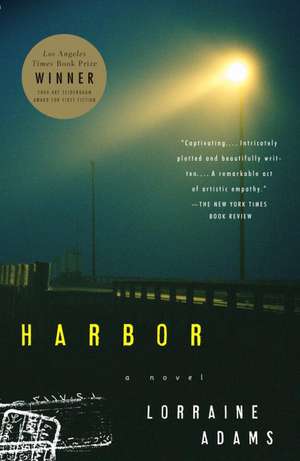

Harbor

Autor Lorraine Adamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2005

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

L.A. Times Book Prize (2004), Guardian First Book Award (2006)

Preț: 81.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 122

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.63€ • 16.14$ • 13.01£

15.63€ • 16.14$ • 13.01£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400076888

ISBN-10: 1400076889

Pagini: 291

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400076889

Pagini: 291

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Lorraine Adams, a Pulitzer prize-winning writer, was educated at Princeton University and was a graduate fellow at Columbia University, where she received a master’s degree in literature. She lives in New York City and is at work on her second novel.

Extras

1

Water never warms in American harbors. They had told him. Shivering, on the high deck of a groaning tanker, told more. He made out a far field of whitecaps many feet below. By the prow, the wind was pulling back the flags into flat, clear pictures. His beard whipped past his face; his overlong hair flew east. His hands and neck burned from insulation he had torn from a crate in the hold that most likely, he realized, after a few days of scratching skin to bleeding, was asbestos. He willed himself to stop but woke to blood caking his shins, under his nails, ridged in his ears. The cold tightened him into a pain that killed sleep.

Aziz could sense there might be other stowaways. On his second try, one he had befriended turned him over to ship’s security, who beat him with mallets, rowed him from the anchored vessel, and deposited him in the care of the harbor police, who pistol-whipped him into unconsciousness and three weeks in a dirty hospital, where his mother cried at his pillow and his brothers brought armloads of food she had cooked, sheets she had washed, an amazing pair of cotton mittens, soft as new white feathers, for his slowly oozing hands. He never saw the informant again, but his brother told him the miscreant had died, not violently but all on his own. He had disappeared for days until his friends found him dead in an alley. It turned out the betrayer had fallen and hit his head.

Now, on his third try, his eyelids were blistered. Some kind of wet kept coming from his ears, which were stoppered, as if someone had poured india rubber into them. After fifty-two days in the hold, his eyes, so long in dark, had just this moment adjusted to the blaring morning. And so he jumped.

He hurtled down in the air for long seconds to the ocean’s surface, whacking into a cold all his preparation had not prepared him for, plunging what seemed to be too far. He tucked his elbows against his rib cage, kicking, and kicked more and farther, all of him roaring up, up, get up. His head popped into the wind and he opened his eyes, locating the pier. He had not gone too far. Stroking across the surface, his arms wore ice sweaters, mercifully insulated from any feeling. On they went, arms of his, down and back, down and back, heavier, heavier, his arms so heavy he wanted to sleep. So he did. He let himself rest, into the deeper water, feeling the weight of it, hoping for its relief. There was something about the possibility of light that came to him. It was like the lamp his mother read beneath. He saw her bent head.

Someone else had jumped with him. He could feel hands at his neck. Maybe more than one. They were choking him. He fought, and at the surface he gurgled out the water in his lungs and saw he was alone. It was then fear found him. He swam in a screaming whistle of panic. There were no thoughts now, just the pumping of his heart. He had been swimming, he guessed, for three hours, or maybe three minutes. He looked a little—squinted, really—and saw he was nearly at the pier. Once there, a ladder, rubberized steel, was slipping from his hands, but then he realized it was grooved this rubber, or was it rippled steel, and his hands were too numb to think they could hang on. So he imagined that they could, and his hands then obeyed this concept, and up he went, peeking over there and down that way to make sure he was alone.

He was. He ran. His jumpsuit, stolen by his father to match the uniforms of the crew, was sopping. Again the command went to his body: You are not cold. Again the body conformed with this idea, and his thinking cartwheeled into the next necessity. There it was—near the Boston train tracks—an abandoned signal booth.

He stripped and started wringing out his clothes. The uniform was canvas, rough and punishing to his blue hands. It is nothing, he told his hands. You are here to function this way, for me, for the future. He had gotten the first of the water out when his hands began to bleed. He dropped the uniform. He would die here, asbestos sickened, ears and eyes mortally infected, the cold finishing him. He pictured his body, stiff across the tracks, as if he had died in the act of trying to gain a conductor’s attention. Then he saw them.

Across the tracks flutters of newspaper pages, hundreds of them, touched down and rose up like kites. He ran toward them in his putrefied underwear with his stretched socks flapping at his ankles. There were so many that even the wind could not keep all of them from him. He gathered them in his arms, scooping and diving like a gull. When he thought he had enough, he sprinted back to the booth and carefully put them inside, securing them with a rusted loop of wire in case the wind gusted in through the door. He pulled off the socks and briefs and laid them and the uniform on the gray stones along the tracks. He closed what was left of the door. The window had been broken, but only slightly, and he began pulling the newsprint toward a slant of sun on the floor, where he lay, building a frail tent that eventually settled into layers of his own heat to warm him.

“He’s drunk.”

“No, he’s a homeless.”

He heard them. With no English, he didn’t know what they said, but he saw in their faces that he was frightening. Back in the signal booth, he had decided what he would say—or, rather, be. He would say nothing and pretend he was deaf. That is how he acted, that is how he was thinking of himself, and that was how this family he had just passed should see him. There were two toddlers, both boys, and their mother and father, getting out of a car. He had tried to hurry past them, but he had discovered it was impossible; his legs would not accommodate his idea of hurrying, and instead he had to be satisfied with a shuffle.

He moved into the blocks of the city, to the skyscrapers, the corridors of shadows so cold, so mean. The sun was out near the water, but that was not where he could find anyone or anything that might warm him. He imagined he would find a church. That was what he was looking for—they allowed people inside, come what may, and he would sleep there, maybe under the altar, or maybe he would find a heavy silk robe in a back room and wrap himself in it, and a priest would happen on him. He was imagining the priest, kindly and old, a face that beamed and was mostly a face of love. How he needed such a face. As he was constructing its possibilities in his head, someone said “Brother.” And so did another one, this time emphatically: “Brother.” They were speaking Arabic to each other. He stopped. The two men, standing near a cart, a cart selling sweatshirts and mugs that said boston, kept talking. The conversation in his head went silent for the first time since he had said goodbye to his father.

Men who spoke Arabic. He had not anticipated anything even remotely this lucky. It was such a gift, such a wonder, that for a full ten seconds he stood rooted to the street, his coldness receding. It would not be good to be who he really was—that much was easy. Deafness, no, but perhaps down on his luck, unstable, if only slightly. He would not beg, no, something more permanent had to be gotten out of this marvel of two men speaking Arabic.

“Brother,” he said, and was surprised at the sound he made. It was a whisper. “Brother!” he shouted, producing only a speaking voice.

They did not hear him. But then, one of them saw him, out of one eye at an angle, and caught his breath.

The other man turned to see, and when he did, Aziz shouted again. “I am sick, help me! I have lost my home.” But when he looked at them, their faces were made entirely of fear, nothing else. He began to feel their fright welling up inside him and the urge to run was enormous, bigger than he could counter, and as he started, he fell, hard, on the pavement, scraping his bare palms, his elbow, reopening the thin scabs from wringing his ship’s uniform, succeeding in shielding only his cheeks and his eyes, from which tears as hot as tea were spilling.

They wanted to take him to a hospital, but he would not let them. So one of them took him to a mosque. He was Egyptian. He worked in a Radio Shack. He went into the mosque talking on his cell phone and came back with donated sweaters, pants, shoes, and a sparkling aquamarine ski jacket. Then he drove Aziz to an apartment in the suburbs, where a wife accepted him with no expression into a hallway with blush-colored broadloom stretching into rooms with white furniture.

The Egyptian took him to the bathroom, where there was a tub that was white, new, and clean. The man explained that there was hot water, right from this handle. Aziz’s parents did not have hot water. Water came in an urn, carried up the hill from the well that everyone shared, and he and his brothers had spent a good deal of their time working out who would be responsible for doing this and who would get excused from it. His mother could have never done it herself, nor would they have ever let her.

The man explained that this was a shower, and he wanted to say, Yes, I know what a shower is; my father managed a hotel for European tourists and I have seen them, I have used them, but he had decided that appearing to be meek and stupid was by far the better course. It also seemed clear that the man did not need to question him too closely to feel an obligation to help him, in however rote a fashion, and that he had little interest in pinning down whether Aziz had jumped off a boat or was a vagrant so imbecilic he could not remember how to bathe.

When the temperature was right, which the man was extremely concerned would be so, putting his hand in and out of the water and turning the handle by bits, he told Aziz to clean himself, to put on the mosque clothes, and that there would be a meal for him in the kitchen. And then he said, “Don’t worry,” and smiled an unaccountably radiant smile that Aziz was entirely unprepared for, and he dropped his head quickly because he did not want this man to see him cry again. When he looked up, the man was gone, the door had closed, and the room was filling with steam. A long high mirror over a pair of sinks was clouding. He walked to it. He looked. He saw a man he knew was himself—of course he knew that—but he was also stained and chapped, almost burned, but he had not been near a fire, he knew, he remembered he had not. He had lobster skin in places, a fearful red on his arms, and then when he looked his elbows were like the wattle of the young roosters his father kept in the back, a glistening crimson he had to keep rubbing the mirror with a towel to see.

He needed to rest on the floor. He could no longer stand. He was crying as quietly as he could, holding himself around his knees on a towel, trying not to spoil the white tile, but he gave up and pulled all the towels he saw in the bathroom down to the floor and lay there on them, watching the water rain in the tub.

He began unbuttoning his uniform, and then he tried to take off one of his socks, and there was his blistered foot, so gelatinous he gasped at the first tug, and then he was shaking. He was faint, and the vertiginous delay in his motions, the slowing of the sound of the shower, finally, finally scared him. He understood that realizing was what was making him weaker than he was. He had to pay attention; he must, above all else, after everything, not let his personhood disintegrate on this bathroom floor in this Egyptian’s apartment. This was what breakdowns were, he said in his own head, enunciating silently, precisely, the sound of his inside voice reminding him of how that voice had been with him in the hold and it was with him now. All a breakdown was was coming up to this kind of a situation, and instead of taking the other sock off the person began howling, or whimpering, or indulged in the real pleasure—for there was no other way to think of it—of feeling how wretched, how lost, how utterly unthinkable and mad everything in his life had been, culminating in a screaming he could not stop and the Egyptian bursting in, while down the hall his children hung anxiously on their playpen bars and the stolid wife pretended she was unconcerned, when inside she was screaming too, something like I am not able to go on, I cannot go on, I will not go on.

He pulled down the uniform and stepped out of it. Then he put one of the towels into the tub, because he did not want to see his clotted bits swirling on the white, and he didn’t want to slip. He put his hand into the rain of water, and it was hot, but not too hot, and the kindness of the Egyptian’s tinkering flooded through him, causing more tears. He put his foot into the tub and on the now-wet towel. He had to grab the side of the tub with his hand and the pain was fierce, but he was no longer shaking and he was only a little dizzy. He forced himself, slowly, because he did not want to shock his system—or he had an idea there might be such a danger after having been cold for so very long—and as he put his shoulder and his neck and part of his back into the falling water, he realized his back was not hurt at all, not the skin, only the muscles were terribly sore. The hot water began to loosen them. He kept his hands out of the water and pushed his head back into the shower and cried, cried and cried as the clarity of the warm sweet water seemed to wash into his brain, not just through his hair. He began to say an old prayer his mother had taught him, his first one. He said it over and over, like a song, while he took the soap and endured the sting it brought. He didn’t look down at what swirled away from the towel in the tub’s bottom. He just washed and washed and rinsed and rinsed. And when the water started to lose some of its warmth, he turned it off and wrapped the towels from off the floor around his head, and his back, and his legs, and he sat there, humming a little, until he heard the Egyptian tap on the door.

From the Hardcover edition.

Water never warms in American harbors. They had told him. Shivering, on the high deck of a groaning tanker, told more. He made out a far field of whitecaps many feet below. By the prow, the wind was pulling back the flags into flat, clear pictures. His beard whipped past his face; his overlong hair flew east. His hands and neck burned from insulation he had torn from a crate in the hold that most likely, he realized, after a few days of scratching skin to bleeding, was asbestos. He willed himself to stop but woke to blood caking his shins, under his nails, ridged in his ears. The cold tightened him into a pain that killed sleep.

Aziz could sense there might be other stowaways. On his second try, one he had befriended turned him over to ship’s security, who beat him with mallets, rowed him from the anchored vessel, and deposited him in the care of the harbor police, who pistol-whipped him into unconsciousness and three weeks in a dirty hospital, where his mother cried at his pillow and his brothers brought armloads of food she had cooked, sheets she had washed, an amazing pair of cotton mittens, soft as new white feathers, for his slowly oozing hands. He never saw the informant again, but his brother told him the miscreant had died, not violently but all on his own. He had disappeared for days until his friends found him dead in an alley. It turned out the betrayer had fallen and hit his head.

Now, on his third try, his eyelids were blistered. Some kind of wet kept coming from his ears, which were stoppered, as if someone had poured india rubber into them. After fifty-two days in the hold, his eyes, so long in dark, had just this moment adjusted to the blaring morning. And so he jumped.

He hurtled down in the air for long seconds to the ocean’s surface, whacking into a cold all his preparation had not prepared him for, plunging what seemed to be too far. He tucked his elbows against his rib cage, kicking, and kicked more and farther, all of him roaring up, up, get up. His head popped into the wind and he opened his eyes, locating the pier. He had not gone too far. Stroking across the surface, his arms wore ice sweaters, mercifully insulated from any feeling. On they went, arms of his, down and back, down and back, heavier, heavier, his arms so heavy he wanted to sleep. So he did. He let himself rest, into the deeper water, feeling the weight of it, hoping for its relief. There was something about the possibility of light that came to him. It was like the lamp his mother read beneath. He saw her bent head.

Someone else had jumped with him. He could feel hands at his neck. Maybe more than one. They were choking him. He fought, and at the surface he gurgled out the water in his lungs and saw he was alone. It was then fear found him. He swam in a screaming whistle of panic. There were no thoughts now, just the pumping of his heart. He had been swimming, he guessed, for three hours, or maybe three minutes. He looked a little—squinted, really—and saw he was nearly at the pier. Once there, a ladder, rubberized steel, was slipping from his hands, but then he realized it was grooved this rubber, or was it rippled steel, and his hands were too numb to think they could hang on. So he imagined that they could, and his hands then obeyed this concept, and up he went, peeking over there and down that way to make sure he was alone.

He was. He ran. His jumpsuit, stolen by his father to match the uniforms of the crew, was sopping. Again the command went to his body: You are not cold. Again the body conformed with this idea, and his thinking cartwheeled into the next necessity. There it was—near the Boston train tracks—an abandoned signal booth.

He stripped and started wringing out his clothes. The uniform was canvas, rough and punishing to his blue hands. It is nothing, he told his hands. You are here to function this way, for me, for the future. He had gotten the first of the water out when his hands began to bleed. He dropped the uniform. He would die here, asbestos sickened, ears and eyes mortally infected, the cold finishing him. He pictured his body, stiff across the tracks, as if he had died in the act of trying to gain a conductor’s attention. Then he saw them.

Across the tracks flutters of newspaper pages, hundreds of them, touched down and rose up like kites. He ran toward them in his putrefied underwear with his stretched socks flapping at his ankles. There were so many that even the wind could not keep all of them from him. He gathered them in his arms, scooping and diving like a gull. When he thought he had enough, he sprinted back to the booth and carefully put them inside, securing them with a rusted loop of wire in case the wind gusted in through the door. He pulled off the socks and briefs and laid them and the uniform on the gray stones along the tracks. He closed what was left of the door. The window had been broken, but only slightly, and he began pulling the newsprint toward a slant of sun on the floor, where he lay, building a frail tent that eventually settled into layers of his own heat to warm him.

“He’s drunk.”

“No, he’s a homeless.”

He heard them. With no English, he didn’t know what they said, but he saw in their faces that he was frightening. Back in the signal booth, he had decided what he would say—or, rather, be. He would say nothing and pretend he was deaf. That is how he acted, that is how he was thinking of himself, and that was how this family he had just passed should see him. There were two toddlers, both boys, and their mother and father, getting out of a car. He had tried to hurry past them, but he had discovered it was impossible; his legs would not accommodate his idea of hurrying, and instead he had to be satisfied with a shuffle.

He moved into the blocks of the city, to the skyscrapers, the corridors of shadows so cold, so mean. The sun was out near the water, but that was not where he could find anyone or anything that might warm him. He imagined he would find a church. That was what he was looking for—they allowed people inside, come what may, and he would sleep there, maybe under the altar, or maybe he would find a heavy silk robe in a back room and wrap himself in it, and a priest would happen on him. He was imagining the priest, kindly and old, a face that beamed and was mostly a face of love. How he needed such a face. As he was constructing its possibilities in his head, someone said “Brother.” And so did another one, this time emphatically: “Brother.” They were speaking Arabic to each other. He stopped. The two men, standing near a cart, a cart selling sweatshirts and mugs that said boston, kept talking. The conversation in his head went silent for the first time since he had said goodbye to his father.

Men who spoke Arabic. He had not anticipated anything even remotely this lucky. It was such a gift, such a wonder, that for a full ten seconds he stood rooted to the street, his coldness receding. It would not be good to be who he really was—that much was easy. Deafness, no, but perhaps down on his luck, unstable, if only slightly. He would not beg, no, something more permanent had to be gotten out of this marvel of two men speaking Arabic.

“Brother,” he said, and was surprised at the sound he made. It was a whisper. “Brother!” he shouted, producing only a speaking voice.

They did not hear him. But then, one of them saw him, out of one eye at an angle, and caught his breath.

The other man turned to see, and when he did, Aziz shouted again. “I am sick, help me! I have lost my home.” But when he looked at them, their faces were made entirely of fear, nothing else. He began to feel their fright welling up inside him and the urge to run was enormous, bigger than he could counter, and as he started, he fell, hard, on the pavement, scraping his bare palms, his elbow, reopening the thin scabs from wringing his ship’s uniform, succeeding in shielding only his cheeks and his eyes, from which tears as hot as tea were spilling.

They wanted to take him to a hospital, but he would not let them. So one of them took him to a mosque. He was Egyptian. He worked in a Radio Shack. He went into the mosque talking on his cell phone and came back with donated sweaters, pants, shoes, and a sparkling aquamarine ski jacket. Then he drove Aziz to an apartment in the suburbs, where a wife accepted him with no expression into a hallway with blush-colored broadloom stretching into rooms with white furniture.

The Egyptian took him to the bathroom, where there was a tub that was white, new, and clean. The man explained that there was hot water, right from this handle. Aziz’s parents did not have hot water. Water came in an urn, carried up the hill from the well that everyone shared, and he and his brothers had spent a good deal of their time working out who would be responsible for doing this and who would get excused from it. His mother could have never done it herself, nor would they have ever let her.

The man explained that this was a shower, and he wanted to say, Yes, I know what a shower is; my father managed a hotel for European tourists and I have seen them, I have used them, but he had decided that appearing to be meek and stupid was by far the better course. It also seemed clear that the man did not need to question him too closely to feel an obligation to help him, in however rote a fashion, and that he had little interest in pinning down whether Aziz had jumped off a boat or was a vagrant so imbecilic he could not remember how to bathe.

When the temperature was right, which the man was extremely concerned would be so, putting his hand in and out of the water and turning the handle by bits, he told Aziz to clean himself, to put on the mosque clothes, and that there would be a meal for him in the kitchen. And then he said, “Don’t worry,” and smiled an unaccountably radiant smile that Aziz was entirely unprepared for, and he dropped his head quickly because he did not want this man to see him cry again. When he looked up, the man was gone, the door had closed, and the room was filling with steam. A long high mirror over a pair of sinks was clouding. He walked to it. He looked. He saw a man he knew was himself—of course he knew that—but he was also stained and chapped, almost burned, but he had not been near a fire, he knew, he remembered he had not. He had lobster skin in places, a fearful red on his arms, and then when he looked his elbows were like the wattle of the young roosters his father kept in the back, a glistening crimson he had to keep rubbing the mirror with a towel to see.

He needed to rest on the floor. He could no longer stand. He was crying as quietly as he could, holding himself around his knees on a towel, trying not to spoil the white tile, but he gave up and pulled all the towels he saw in the bathroom down to the floor and lay there on them, watching the water rain in the tub.

He began unbuttoning his uniform, and then he tried to take off one of his socks, and there was his blistered foot, so gelatinous he gasped at the first tug, and then he was shaking. He was faint, and the vertiginous delay in his motions, the slowing of the sound of the shower, finally, finally scared him. He understood that realizing was what was making him weaker than he was. He had to pay attention; he must, above all else, after everything, not let his personhood disintegrate on this bathroom floor in this Egyptian’s apartment. This was what breakdowns were, he said in his own head, enunciating silently, precisely, the sound of his inside voice reminding him of how that voice had been with him in the hold and it was with him now. All a breakdown was was coming up to this kind of a situation, and instead of taking the other sock off the person began howling, or whimpering, or indulged in the real pleasure—for there was no other way to think of it—of feeling how wretched, how lost, how utterly unthinkable and mad everything in his life had been, culminating in a screaming he could not stop and the Egyptian bursting in, while down the hall his children hung anxiously on their playpen bars and the stolid wife pretended she was unconcerned, when inside she was screaming too, something like I am not able to go on, I cannot go on, I will not go on.

He pulled down the uniform and stepped out of it. Then he put one of the towels into the tub, because he did not want to see his clotted bits swirling on the white, and he didn’t want to slip. He put his hand into the rain of water, and it was hot, but not too hot, and the kindness of the Egyptian’s tinkering flooded through him, causing more tears. He put his foot into the tub and on the now-wet towel. He had to grab the side of the tub with his hand and the pain was fierce, but he was no longer shaking and he was only a little dizzy. He forced himself, slowly, because he did not want to shock his system—or he had an idea there might be such a danger after having been cold for so very long—and as he put his shoulder and his neck and part of his back into the falling water, he realized his back was not hurt at all, not the skin, only the muscles were terribly sore. The hot water began to loosen them. He kept his hands out of the water and pushed his head back into the shower and cried, cried and cried as the clarity of the warm sweet water seemed to wash into his brain, not just through his hair. He began to say an old prayer his mother had taught him, his first one. He said it over and over, like a song, while he took the soap and endured the sting it brought. He didn’t look down at what swirled away from the towel in the tub’s bottom. He just washed and washed and rinsed and rinsed. And when the water started to lose some of its warmth, he turned it off and wrapped the towels from off the floor around his head, and his back, and his legs, and he sat there, humming a little, until he heard the Egyptian tap on the door.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Captivating. . . . Intricately plotted and beautifully written. . . . A remarkable act of artistic empathy." --The New York Times Book Review"Luminous. . . . Heart-stopping. . . . Adams draws her characters with compassion and humor." --The Washington Post Book World “Razor-sharp. . . . A vivid, fast-paced entry into an immigrant’s story that is part thriller, part social commentary and at times darkly funny. . . .Terrific.” –The Miami Herald “A great, gutsy first novel. . . . Outstanding.”–Entertainment Weekly “Deeply introspective and tantalizingly beautiful. . . . Harbor is one of the best new novels of the year.”–The Baltimore Sun“Complex, vibrant, and imaginative . . . as compelling as it is necessary.”–Esquire"Endlessly fascinating. . . . Convincing and utterly compelling." --Time"Mesmerizing. . . . A ripping read. . . . A heart-rending cautionary tale of American justice gone awry." --Los Angeles Times Book Review“Remarkable . . . brilliant. . . . Compelling and haunting. . . . Adams creates an exquisite tension in a character who is at once unseen and yet hunted, both estranged from society and deeply enmeshed in a complicated social order. . . . [Harbor is] a work of art that lifts the veils of many of our assumptions that have formed since 9/11.” --Boston Globe"[A] great, gutsy first novel. . . . Outstanding." --Entertainment Weekly"Fascinating. . . . [Adams] writes convincingly from within the hearts and minds of her characters. Though topical, the narrative flies well beneath the headlines." --The Oregonian"A chilling story of identity and loss culled from real-life experiences. . . . A cautionary tale that asks readers to be open-minded. . . . [Adams] never loses sight of a story that alternates between incredible moments of joy and sadness." --Pittsburgh Tribune-Review "Insightful. . . . Adams adds welcome shading to the usual portrayal of the war on terror." --U.S. News & World Report “A disturbing tale where suspicion is enough to trump innocence and the consequences of naivet? are potentially disastrous. . . . Adams humanizes the terrorist threat and convincingly shows how a confined worldview can breed generalizations that may hatch tragic consequences." --San Francisco Chronicle“Brilliant. . . . A strong and disturbing book.” --Annie Proulx, Book-of-The Month Club News “Adams displays a gift for detail and character that takes us fully inside the complex systems of survival, kinship, and religious ideology which form Aziz’s world.” --The New Yorker“Adams is a sharp observer of the current war-on-terror politics. [Harbor] counters the media’s easy perceptions in our age of xenophobia by immersing readers in the depths of myriad characters.” --The Dallas Morning News"Mesmerizing. . . . A timely and grippingly written book, Harbor helps give the war on terror a human face." --People “Adams drags her characters through the wheels of fate and makes them sing . . . . [Her] sentences move with speed and visual economy, but also contain poetic beauties. . . . A compelling story with great characters--timely, suspenseful and profound.” --Ruminator Review“A powerful look at America through immigrant eyes that is not only timely but essential in our post-9/11 society.” --Ft. Worth Star-Telegram“[Adams] writes with verve and is so convincing that it often seems that this is a true story instead of fiction . . . A story about complex interaction between human beings of greatly differing cultures, written by an author of enormous talent.” --Deseret Morning News

Descriere

A powerful first novel that engages the tumultuous events of today, "Harbor" is at once an intimate portrait of a group of young Arab Muslims living in the United States, and the story of one man's journey intoPand out ofPviolence.

Premii

- L.A. Times Book Prize Winner, 2004

- Guardian First Book Award Nominee, 2006