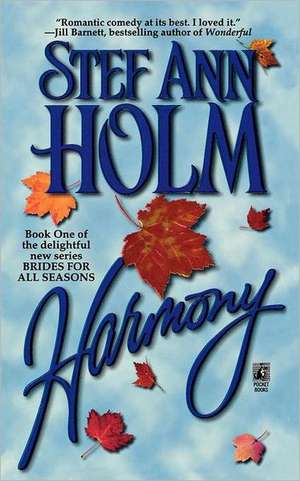

Harmony

Autor Stef Ann Holmen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 iul 2010

When prim deportment teacher Edwina Huntington finds herself co-owner of a warehouse with rugged sportsman Tom Wolcott, togetherness in Harmony, Montana, is anything but. And as soon as they discover that they clash more than their choices of paint color—lemon yellow and slaughter red—sparks fly in every shade. Edwina wants to educate women on the ceremonies of society, as preparation for marriage—though she’s resigned to spinsterhood. Tom hasn’t thought much about matrimony one way or the other—his world of big guns and big grizzlies has kept him plenty occupied—until now.

Equally fierce-willed, Edwina and Tom square off for a showdown. But they’re both helpless in the face of the powerful attraction that explodes between them, and soon the battle of the sexes rages in a new direction…true love.

Preț: 114.51 lei

Preț vechi: 142.53 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.91€ • 22.64$ • 18.24£

21.91€ • 22.64$ • 18.24£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781451614053

ISBN-10: 1451614055

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:10000

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

ISBN-10: 1451614055

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:10000

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Extras

Chapter One

As Tom Wolcott rode his piebald into Harmony, a party of six exhausted but satisfied men fell in behind him on plodding horses. Their duckcloth hunting suits, spanking new a week ago, now bore smatterings of mud, dung, and blood. But they'd gotten their great outdoors thrill in Montana, having bagged between them two elks, a cougar, and a half-dozen hares.

Cutting across Main Street toward Hess's Livery, Tom spied Shay Dufresne lounging in the sunlit double-wide doorway. Seeing his old friend and new partner, Tom sat taller in the saddle and his mood lightened. They'd known each other since boyhood, having grown up in the same Texas town. After turning eighteen, they'd traveled the western countryside together. They separated for a while, each trying their hand at different ventures, but now Tom had convinced Shay to come to Montana from Idaho. This would be the last time he had to take a group of greenhorn Easterners on a hunting trip. From now on, Shay would be in charge of the expeditions while Tom got his arms-and-tackle store off the ground.

"Hey, partner," Tom said in a greeting, reigning in and dismounting. He,held onto the bridle leathers with one gloved hand while gripping his friend's hand in the other. "When'd you get in?"

"Three days ago." Shay gave him a warm smile, laugh lines etching creases at the corners of his eyes. His face was a bit angular, his nose a little too pointed; but he had a gaze that bespoke loyalty and trust.

Tom spoke around the cigarette in his mouth. "Max put you up?"

"As best he could." Shay withdrew his hand. "With all the crates and boxes you have stacked to the rafters, there's barely a free inch left to put up a cot."

Aside from stabling over two dozen riding and packhorses with Max Hess, Tom had been using the livery as his warehouse and temporary business quarters.

"It'll all be moved out tomorrow." Over his piebald's rump, Tom called to the grin-happy city slickers. "Gentlemen, move those horses into the stables and Max will see, to them. Unhitch your gear and trophies. There's a butcher on Hackberry Way who'll dress the meat, and if you want those horns mounted, I'm the man to see."

"By jinks, I want the whole head and neck on a lacquered wall plaque," came a jovial reply from the Bostonian banker.

"I can do that." Just as Tom tethered his horse on the branch of the only tree in front of the, livery, a droopy looking bloodhound came trotting up. The dog shook off and shot his owner with Evergreen Creek water "Dammit, Barkly, you could have done that elsewhere."

Barkly sat on his haunches; wet, loose skin hung in folds about his head and neck. His nose lifted toward Tom, and he made a grunting noise through his black nostrils.

"Don't tell me anything I don't know," Tom said off-handedly to the canine. "Shay, you think you can help them undo those diamond hitches? They're liable to take their knives to the ropes if they can't work the knots loose." With a flick of his wrist, Tom tossed his smoke on the ground and crushed the butt with the instep of his boot. "I need to make myself feel human again."

Tired and dirty, Tom longed to shed the navy lace-up-at-the-throat sweater that hugged his shoulders. Dust-coated Levi's and chaps encased his legs. His knee-high boots bore the nicks of twigs and pine needles. The stub-bib phase of a beard had lapsed into grubby; and he smelled like campfire smoke, game, and wet dog. He wanted nothing more than to soak in a hot sudsy tub, 'then slip into a fresh set of clothes.

"Making yourself human will have to wait. A lawyer came by twice while you were gone. Last Tuesday he talked with Max, then yesterday I spoke with him." Shay slipped his hand into his pocket, produced a calling card, and read, "Alastair Stykem. You know him?"

"I've never met him, but I know he's got an office on Birch Avenue."

"He's real anxious to talk to you."

"About what?"

Handing Tom the card, Shay shrugged. "Hell if I know. I told him you were expected back today. He pressed me for a time, so I gave him one. You've got a two o'clock appointment at his office."

Tom swore beneath his breath. "What time is it?"

Shay took a watch out of his vest pocket. "Two-ten."

Gazing at Tom, he said, "I figured you'd be in by noon."

"We got that cougar just before lunch, and we had to pack it."

"You'd better get on over there. I'll handle things here."

Tom put a thumb to his hat brim and pushed back then rubbed the grit off his brow. "Stykem didn't tell you what this was all about?"

"No. He just said he needed to talk to you. And that it was important."

Undoing the buckle of his gun belt, Tom looped the leather strap holstering his revolver over the saddle horn; he slung his chaps across the seat.

To the dog, Tom instructed, "Wait," then to Shay he said, "Whatever this is, it'd better not take long."

Leaving the livery behind, Tom walked down Main for a block, giving cursory glances to the post office, Storman's Feed and Fuel, and Buskala's Boarding House. He had become accustomed to the business buildings being brick rather than the wood that was the norm where he and Shay hailed from. Nearly all were two stories and had canvas awnings of various shapes and heights that overhung the high board sidewalks. The corner supported the Blue Flame Saloon. A turn on Birch Avenue and he passed the barbershop, the druggist's, Treber's Men's Clothing store, and the Brooks House Hotel.

He'd rather have been going in the opposite direction so that he could take a look at the warehouse on Old Oak Road. A vacant lot away from the blacksmith's, but at least not across the railroad tracks by the lumberyard and flour mill; stood the building he'd bought from Murphy Magee. The interior measured a good-size, comfortable enough to stock his merchandise and display his trophies and still have plenty of aisle room. For the past few months, he'd spent nearly all his income on sporting goods to fill his store. Tom had been taking men on hunting trips for the better part of a year. The trial period was over. His advertisements in eastern papers had proved to be successful in attracting suit-and-collar types out West for camping adventures they couldn't experience in the big cities.

Tom felt at ease in the woods, but the boisterous antics of dandies grated on him after the first day out. Being isolated with men sporting handlebar mustaches and rifles with superfine sights -- front and rear -- to guarantee a sure shot was not his idea of a challenge. Real gamesmen had to actually work at stalking their prey; not be so out of shape they were unable to hike up hill. Nor would they pine over the loss of forbidden flasks of brandy; Tom allowed no liquor in the campsites.

But now that Shay had arrived, Tom would stay behind in the store, letting the would-be hunters buy as many gadgets as they pleased while his partner took them out on the trail. Tom wasn't opposed to all the newfangled gadgets that helped a man bag his game with relative ease; he just preferred not to use them.

Grasping the handle of a door, Tom let himself inside a lobby that had the faint scent of ink. He crossed the granite floor tiles to a narrow stairwell on his right. At a single hall featured two doors. In gold letters the first had ALASTAIR STYKEM, ATTORNEY AT LAW spelled out. Tom went in the office.

A young woman in a high-buttoned blouse sat behind desk, plucking at keys of a typewriter with one finger. On his intrusion, she looked up and down, then up again; then left and right as if she planned on fleeing. A pair of wire bow spectacles perched on her nose. Black ink smudged her forehead and chin. But it wasn't the ink that made him stare at her -- it was the color of her hair. A vivid red-orange. Like Indian paintbrush petals.

"M-may I h-help you?" she stammered, not meeting his gaze while pushing her glasses farther up her nose. an ink smear across the freckled bridge.

"I have a two-o'clock appointment."

"M-Mr. W-Wolcott?"

His nod went ignored because she refused to lift her head. He had to resort to saying, "Yes."

"Th-they've been waiting for you."

They?

The woman stood, kept her gaze pinned to the carpet's cabbage rose pattern, and took a few steps to the paneled door. Knocking, she stuck her head through the crack she'd opened. "Mr. Wolcott is here," she announced in a clear, smooth voice.

"Good. Send him in." An exasperated breath punctuated the man's next words. "Crescencia, wipe that type-writer ink off your face."

"Yes, Papa."

Crescencia withdrew, then backed toward the desk so Tom couldn't see her face -- as if he hadn't already. Mumbling into the hankie she'd produced from a fold in her skirt, she said, "Y-you may go in, M-Mr. W-Wolcott."

Tom slipped by the desk and nudged the interior door the rest of the way open with his shoulder.

Alastair Stykem sat with his back to the window, sheer curtains deflecting the intensity. of afternoon sun. Upon Tom's entrance, the lawyer rose from behind a massive oak desk and extended his hand. Tom had to step farther into the room to grasp it. After the formality, he felt a presence to his right, and looked down at the occupant in the chair. A pair of pale, mint-colored eyes leveled on him. The woman had rich mahogany hair swept away from her oval face. Huge bows ran around the band of her hat, which sprouted a large, blue chrysanthemum

The lawyer's voice pulled Tom's gaze away. "Mr. Wolcott."

"Stykem," Tom said in acknowledgment.

"You know Miss Huntington?"

Unbidden, Tom's glance once again landed on the seated woman. "I've seen her around." But he had never inquired after her. There was an old-maidish air to the way she carried herself. He would have guessed her to be ten years older than him. But up this close, he could see he'd been mistaken. He had to have had her by at least five.

"Well then, please sit down, Mr. Wolcott."

Tom lowered himself onto one of the plump leather chairs, but he didn't feel at ease in the cushioned depths. Anxiousness made him reach for the half-pack of Richmonds in his front pants pocket, but he stopped himself midway when he saw the disapproval on Miss Huntington's face.

"I see no reason for preamble," Alastair continued. "Miss Huntington has known about the situation for a week, so I'll come right to the point." The lawyer steepled pudgy fingers against his paunch. "Murphy Magee is dead. He fell into a sewer hole last Monday night and sustained fatal injuries."

Tom regarded Alastair quizzically for a moment. Some sixth sense made him proceed with care. "I'm sorry to hear that. Murphy was a regular guy."

"Be that as it may, a problem has arisen that only Mr. Magee could have settled. Since he's not with us, the case has been brought to my attention by the county he recorder's offine in hope that I can mediate a peaceful conclusion to this unfortunate situation."

The words county recorder's office cautioned Tom into silence. Resting his foot on a dusty knee, he pressed his back into the chair and depicted a comfort he didn't feel. Before he'd left Tuesday morning, he'd slipped the receipt Murphy had given him beneath the door to the recorder's office so that he could pick up the deed when he got back into town. Obviously something had gone wrong. Maybe the clerk needed more information. Maybe Murphy hadn't written out the bill of sale correctly. The man had been drunk when they'd made the transaction at the Blue Flame. Even if Murphy had messed up, why was Miss Huntington sitting primly in the chair next to him?

Alastair opened a folder before him and produced two documents. He held them out for Tom to see. "As you can read, the warehouse at 47 Old Oak Road is deeded to both you and Miss Huntington. The clerk had recorded Miss Huntington's title on a Monday afternoon, and yours on a Tuesday morning. For legality's sake, it doesn't really matter whose was recorded first or last. Both are binding. If Mr. Magee was here with us, he could explain how he happened to sell both of you his warehouse. By his taking money twice, he's committed fraud" -- the lawyer gave a slight shrug -- "but who can prosecute a dead man?" After a chuckle, he answered himself. "My late wife would say I would if I could recover something.

Tom saw no humor in that. Accentuating the annoyance he felt with Stykem, Murphy, and Miss Huntington, who had begun to rummage through her purse, Tom brought his foot down hard on the floor and leaned forward. "What are you trying to tell me, Stykem?"

"You and Miss Huntington are both the legal owners of the parcel known as lot four, block two."

A cold knot formed in Tom's gut. Muscles on hisforearms bunched as he took hold of the chair's arms and gripped the padded leather. If Murphy, Magee weren't dead already, he'd go for the man's throat. He should have known better than to do business with a man basted with whiskey. But Tom hadn't wanted to leave for the week without having secured the warehouse, so the transaction had taken place in the saloon.

He heard a dainty cough and sniff, then glared at Miss Huntington. "What do you have to say about this?"

Miss Huntington had brought out a hunk of lacy stuff and lifted the edge to her nostrils. "Mr. Stykem, I find I'm feeling a little light-headed. Could you please open the window for ventilation?"

"Open the window?" Tom echoed. "You've known about this for a week. If anyone is sick, it's me!"

She kept her eyes forward. Curved lashes caught his attention; they were softly fringed and the exact shade of her hair. His gaze lowered. A kind of feathery blue fabric gently outlined her figure, cutting in at her narrow, sashed waist. He knew enough about ladies' fashions to appreciate that she wore pleats, bows, and trims in all the right places. As his eyes lingered on the controlled rise and fall of her breasts as she breathed into her handkerchief, he became aware of what he was doing. With a silent curse, he instantly stopped his appraisal of her.

Tom laid his palms on his thighs. "What now?"

The curtains fell back into place after Alastair unlatched the window lock and lifted the sash. He took his seat and pointedly gazed at the both of them. "Mr. Magee died on the installment plan. Meaning he owed people money." A shuffle of papers, and Stykem came up with a long list that he beganto read from. "Eight dollars and forty-two cents to one Madame Beauchaine of Tut Tut, Louisiana for astrological readings, ten cents to Dutch's Poolroom for dill pickles, three hundred and twenty-two dollars and four cents to the Blue Flame for a bar bill" Alastair waved his hand over the paper and set it down. "Et cetera, et cetera. Frankly, I don't know why he held on to the warehouse as long as he did. He could have used the revenue."

"What are you getting at?" Tom questioned.

"Mr. Magee's estate can't give a refund to either of you. After debtors get hold of what he has left of the money you gave him, there'll barely be enough to cover my fees." Stykem bent his fingers and cracked the knuckles in succession from pinkie to thumb. "I didn't want to suggest this without your being together, but one of you could buy the other out. Of course, that will mean you're paying twice for the property. You'll, have to ask yourself how badly do you want it." Wiry brows arched as he waited for their reaction. Neither of them moved; so the lawyer continued. "Miss Huntington, you pay Mr Wolcott five hundred dollars and the warehouse is yours. Or, Mr. Wolcott, you pay Miss Huntington four hundred and fifty dollars, and the warehouse goes to you."

"Four hundred and fifty?" came an indignant female squeak. "Mr. Stykem, I paid Mr. Magee five hundred dollars for the property."

"Yes, my dear, that is true. But the deal Mr Wolcott worked out with Mr. Magee allowed him to buy the property for fifty dollars less than you paid."

Miss Huntington's rose-colored mouth thinned, and a blush crept up the ivory column of her neck. She was either highly embarrassed or angered to the boiling point. Tom couldn't tell for sure. He didn't really care. All he knew was he didn't have an extra four hundred and fifty dollars with which to buy her out. Nor, couuld he afford for her to pay him five hundred for the right of ownership. No other site could enhance his store the way Magee's's place could.

The warehouse on Old Oak Road was tailor-made for his needs. It was tucked away from the town's populace, and the area surrounding it was semiwooded. A vacant lot sat on either side and to the rear of the building. He'd planned on setting up a target practice area out back, along with extension traps. Since stray clay pigeons and bullets would be no threat to another business or other persons, he didn't need a permit for open firearms other than the formality of an intent notice filed with the police department. He couldn't have that luxury in another building within Harmony's town limits.

"Well, hell," Tom said at length, exhaling. "That buyout idea doesn't work for me."

"Miss Huntington?" Alastair queried.

"My business adviser would caution me against it. My funds are tied up and cannot be released to buy the building a second time." The piece of lace had been lowered onto her lap. She wound a corner of the handkerchief around her slender forefinger, then unwound it. Wind, unwind. Wind, unwind.

"There ought to be some kind of law that says the warehouse is mine," Tom argued.

Miss Huntington cleared her throat. "Excuse me, but I paid for it first. After all, it was recorded to me on a Monday, and you on a Tuesday." Then, ignoring him, she spoke directly to the lawyer. "Mr. Stykem, don't take this the wrong way, but can't we approach a judge who has a higher definition of the law than you? Surely he could settle this as legally as possible."

"I've already consulted with Judge Redvers, in Butte. When it comes to hard cases, he's got a reputation for using common sense as much as law." A toothpick rolled from the edges of Stykem's mountain ofdocuments, and he absently fiddled with it. "Judge Redvers said he'd rule on any action like King Solomon. He'd cut the baby in half."

"We aren't fighting over a baby," Tom grumbled.

"I know that," Stykem cut in. "The baby is a hypothetical. The judge would rule to divide the warehouse, so there's no point in wasting time bringing the case to him when we already know what he'd say."

Miss Huntington's next query held a note of crispness. "So now what?"

"Now we'll have to proceed the only other way." Stykem went to yet another folder and, produced a bid form. "I've taken the liberty of having Mr. Trussel look at the property. For a moderate fee, he can construct a wall that will evenly divide the building. And he can frame in another entry door on the east side. You both would have your own entrances; however, he advised me that the storage room in the rear that runs the length of the building cannot be altered. Several of its posts are supports to the roof and tampering with them could be detrimental to the building's soundness. You would each have your own access to the area, only it wouldn't be sectioned in two like the main interior."

Tom mulled over the possibilities. He'd have to make everything fit in half the space. Perhaps he could still stock the same amount, but the aisles would be cramped. If he had to overload the walkways, where would he put his grizz? The bear had, weighed six hundred pounds before he'd stuffed it. There had to be room for his mammoth eight-point bull elk and the lynx he'd, gotten last winter. He had an endless amount of taxidermic fowl and small rodents that required counter space. Hunters liked to see trophies on display. And Tom had a shitload of them.

Massaging his temple, he fought against the idea of sharing the building with a woman who had a flower on her hat bigger than a moose's butt. He didn't like the thought of having to compromise with her. But it seemed to be the only choice he had.

"Forgive me saying so, Mr. Stykem, but I shouldn't have to pay half."

Tom gave the lawyer no opportunity to respond. "Sure you'll pay half."

Her gaze landed on his. "I shouldn't have to yield another cent." The tuft of lace resumed residency at her nostrils, and she spoke through the weblike pattern. "Already you've gotten your part of the building for fifty dollars less than me."

Alastair cut in. "I'm sorry, Miss Huntington, but the fact of the matter is, it doesn't matter if he paid one penny and you paid one thousand for the place. You both negotiated separate deals that have nothing to do with one another -- except that they're for the same property."

She straightened. "Then my side should be at least a foot wider than his."

"There again, Miss Huntington, you can't measure against the original cost of the building. Both halves will have to be equivalent." A gold signet ring reflected light as Alastair twirled it on his finger. "So, are we all in agreement?"

"I'm afraid you leave us no other choice." Miss Huntington took the words right out of Tom's mouth.

"Mr. Wolcott?"

"It's like the lady said."

"Good, then everything is settled." Stykem tidied the documents on his desk. "It will be up to both of you to inform the postmaster that you'll each be getting your own mail. Miss Huntington, your address will be 47-A Old Oak Road, and Mr. Wolcott, your address will be 47-B Old Oak Road. I'll speak with Mr. Trussel and have him get started with the renovations right away."

Miss Huntington stood, then walked stiffly around the back of her chair to the umbrella stand and retrieved a folded parasol. "Good day, Mr. Stykem."

She'd gone out the door when Tom went to his feet and shoved his left hand in his pocket. "Stykem, I can't say it's been a pleasure."

The lawyer laughed. "I hear that a lot."

Tom stepped into the receiving office, where Miss Huntington and Crescencia were exchanging words. As soon as he came into the room, they shut up. He went past them, Crescencia saying, "G-good day, M-Mr. W-Wolcott."

"Yeah, same to you." He let himself out, thinking he heard Miss Huntington say something like, "Don't you fret about it, dear. You shall overcome, I assure you." Whatever that meant.

Once down on the street level, Tom went for his cigarettes and lit one while he stood on the boardwalk. As he waved out a match, Miss Huntington exited the building. She gave him a quick gaze, then proceeded. He had to go in her direction, so he trailed her. At the corner, they were forced to wait before crossing while the Harmony Fire Department backed its No. 1 engine into the firehouse.

He stood behind her. In height, he had at least ten inches on her, so he had an aerial view of the top of her hat. The air was as fresh as it could get out here, yet she started up with the handkerchief routine again. Then the reason hit him, dragging his pride down a notch. She thought he stunk. Hell, he knew he did. No wonder she'd had Stykem open the window.

On the toes of her proper shoes, Miss Huntington inched her way toward the curb. What did she think he was? A pig? He didn't like to be this in need of a bath, but when had there been time to put on his coattails before delivering himself to her presence?

Now that he realized she was bothered by him, he cut the distance between them. His chest nearly pressed against her shoulder blades. He would have gone in even further if his jaw hadn't been in jeopardy of being rim through by the lethal pin sticking out of her hat.

When she moved again, she went a bit too far and teetered. He grabbed her by the elbow before she could fall into the street.

"What's the matter, Miss Huntington?"

"Nothing." She'd swung her body halfway around so that she could gaze at his face. Exotic green eyes held onto him as physically as his hand held onto her arm. It was a damn shame such pretty eyes belonged to a guardian of morality.

The silkiness of her dress felt, good beneath his fingertips, so he didn't readily release her. Because he'd been so bogged down in his business, it had been a while since he'd held a woman and explored the delights of perfumed skin. He wouldn't have guessed that by touching her elbow he could become aroused. But damn if he wasn't.

What had started out as teasing her was teasing him.

He let her go, then took a deep pull on his cigarette.

"What are you going to do with your side?"

Her voice intruded in his head. Regaining a sense of indifference, he replied, "Sell sporting goods."

Speculation filled her gaze. "Oh..."

He felt obligated -- not that he wasn't curious -- to ask, "What are you going to do with your side?"

"Open a finishing school for ladies."

"What for?"

"To educate them in the rules, usages, and ceremonies of good society."

"You mean to make them like you."

Her chin lifted, and for a minute he thought she might jab him with the point of her unopened parasol. "I should hope."

The boardwalk traffic began to move, but Miss Huntington stayed. "By the way, I hope you aren't allergic." She said the word as if she wished he was. "I'll be bringing my cat."

After giving her an uneven smile, he crossed the street and called over his shoulder, "No problem. I have a dog who loves cats."

Edwina stood on the corner watching Mr. Wolcott disappear from her view. She made a mental list of all his offenses in the presence of her company.

Number one: Not removing his hat.

Number two: Reaching for cigarettes.

Number three. Not practicing personal hygiene.

Number four Openly staring at her without her invitation.

Number five. Using a swear word.

And number six: Verbally insulting her good character.

A half-dozen demerits. She would have counted touching her if his gesture hadn't been somewhat of a valiant attempt to keep her from falling into the street. But then he'd forced her into moving too far off the boardwalk.

Number seven: Unacceptable bodily contact.

In spite of herself, faint tingles rushed to the spot he'd touched. His fingers had been firm yet gentle when he'd held her elbow. Crystal blue eyes had scowled at her beneath down-turned brows. A mane of tawny hair laid in a disarray across unscrupulously- wide shoulders. At first his gaze had been bright with humor, but then it had changed to a dark, unfathomable hue. She didn't want, to think about what he'd been thinking about.

The man was a toad. She had to give today's women the opportunity to choose the right husband for themselves and not settle for whoever lived in Harmony's tight-knit circle. Ironically, Mr. Wolcott had unwittingly been her helper.

She had been aware that he entertained Eastern-gentleman by taking them on hunting jaunts. The steady visits of well-bred clientele had given her an idea this past summer.

Harmony's eligible young ladies should be introduced to men of respectable professions -- not that the selection in town was dire. But those who stayed after graduating the normal school rarely set their sights beyond a trade or working at Kennison's Hardware Emporium. And the handful who had aspirations of bright futures left for college and didn't often return once they saw what the outside world had to offer them.

While in Chicago attending business college, Edwina had fallen in love with a man-about-town. Their relationship had been chocked with spontaneity, but it hadn't resulted in marriage. Smarter now, she realized she lost herself to a beau who heeded his mother's opinions rather than his heart. By enlightening girls about the facets of courtship -- especially the do's and don'ts -- she hoped to empower them to know the difference between real love and passing affections. There were good men who came from large cities, and just because Edwina had chosen the wrong one didn't mean that she thought all Easterners were molly-coddled. On the contrary, those who sought the West for recreation were of a different breed. She saw them as adventure-seekers.

Where Mr. Wolcott had thought of a way to bring gentlemen to their small Montana town, Edwina had thought of a way to show those very gentlemen that charming women didn't necessarily reside only on city streets. Perhaps her students would impress the men into staying, and those marriages could add a diversity to the community.

Edwina crossed the street, then proceeded on Main toward her residence on Sycamore Drive. Sugar maples shaded the walkway, their leaves showing vague signs of the autumn change. The season hadn't taken hold yet. Though nights brought a shivering chill, days could be warm beneath the buttery sunshine.

She had a seven-o'clock meeting that evening at her home. A cake needed to be baked and the silver tea service brought out. Tonight was an important night. Everything had to be perfect. The afternoon had upset her, but at least she'd been apprised of the, situation before Mr. Wolcott had come to the law office.

When she'd first learned about Mr. Magee's selling the warehouse twice, she'd wanted to give him a stern piece of her mind. But immediately thereafter, she'd been informed that he had died in an accident, and she'd felt horrible for having wished he would have one. Only in her mind, he hadn't died... merely suffered some blood loss with a fracture. Or two.

She could hardly bear to think that she'd spent what precious little money she had left in the bank -- just over five hundred dollars -- much less being asked to come up with another five hundred with which to buy out Mr. Wolcott. To add insult to injury, when she found out that she'd paid fifty dollars more than him -- for the exact same property -- she'd felt as if Mr. Magee had made a mockery of womankind. He must have thought females pretty stupid when it came to business deals.

Edwina's lips curved down. Well, she'd been stupid enough, but right now that was a moot point.

Of course she didn't have a business adviser. But after finding out that she'd been made a fool of once, she wasn't about to be one twice. Especially not in front of Mr. Wolcott. He needn't know that she couldn't afford to buy him out.

She wouldn't have had this trouble if she'd taken that quaint suite in the Ellis building. But the deposit and monthly rent would have sent her to the poorhouse even quicker than she was already headed.

Turning down a sycamore-lined street with Queen Anne homes, expansive lawns, and multitudes of color in both trim and landscape, Edwina clicked the tip of her parasol on the hard-packed ground.

Sporting goods. Why did he need to sell that nonsense? The Sears and Roebuck catalogue sold the basics a man needed, and even then, the few items she'd seen while flipping to the ladies' section had looked rather silly.

A mere wall dividing them would surely not be enough. Among other things, his remark that his dog would eat her cat had cinched that. She'd take a waffle iron to that mongrel if it harmed so much as one hair of her precious Honey Tiger's fur.

But for the good of all the marriageable young ladies, Edwina would endure any inconvenience she had to. She longed to see happy homes with loving husbands, celebrating christenings, birthdays, and anniversaries. Of course, that wasn't to be for her...No gentleman would ever marry her if he knew the truth.

So Edwina Huntington had to pretend to be an unapproachable old maid, uninterested in affections. Because she had a deep, dark secret. One that she'd rather take to a presumed spinster's grave than ever -- ever -- reveal.

Copyright © 1997 by Stef Ann Holm

As Tom Wolcott rode his piebald into Harmony, a party of six exhausted but satisfied men fell in behind him on plodding horses. Their duckcloth hunting suits, spanking new a week ago, now bore smatterings of mud, dung, and blood. But they'd gotten their great outdoors thrill in Montana, having bagged between them two elks, a cougar, and a half-dozen hares.

Cutting across Main Street toward Hess's Livery, Tom spied Shay Dufresne lounging in the sunlit double-wide doorway. Seeing his old friend and new partner, Tom sat taller in the saddle and his mood lightened. They'd known each other since boyhood, having grown up in the same Texas town. After turning eighteen, they'd traveled the western countryside together. They separated for a while, each trying their hand at different ventures, but now Tom had convinced Shay to come to Montana from Idaho. This would be the last time he had to take a group of greenhorn Easterners on a hunting trip. From now on, Shay would be in charge of the expeditions while Tom got his arms-and-tackle store off the ground.

"Hey, partner," Tom said in a greeting, reigning in and dismounting. He,held onto the bridle leathers with one gloved hand while gripping his friend's hand in the other. "When'd you get in?"

"Three days ago." Shay gave him a warm smile, laugh lines etching creases at the corners of his eyes. His face was a bit angular, his nose a little too pointed; but he had a gaze that bespoke loyalty and trust.

Tom spoke around the cigarette in his mouth. "Max put you up?"

"As best he could." Shay withdrew his hand. "With all the crates and boxes you have stacked to the rafters, there's barely a free inch left to put up a cot."

Aside from stabling over two dozen riding and packhorses with Max Hess, Tom had been using the livery as his warehouse and temporary business quarters.

"It'll all be moved out tomorrow." Over his piebald's rump, Tom called to the grin-happy city slickers. "Gentlemen, move those horses into the stables and Max will see, to them. Unhitch your gear and trophies. There's a butcher on Hackberry Way who'll dress the meat, and if you want those horns mounted, I'm the man to see."

"By jinks, I want the whole head and neck on a lacquered wall plaque," came a jovial reply from the Bostonian banker.

"I can do that." Just as Tom tethered his horse on the branch of the only tree in front of the, livery, a droopy looking bloodhound came trotting up. The dog shook off and shot his owner with Evergreen Creek water "Dammit, Barkly, you could have done that elsewhere."

Barkly sat on his haunches; wet, loose skin hung in folds about his head and neck. His nose lifted toward Tom, and he made a grunting noise through his black nostrils.

"Don't tell me anything I don't know," Tom said off-handedly to the canine. "Shay, you think you can help them undo those diamond hitches? They're liable to take their knives to the ropes if they can't work the knots loose." With a flick of his wrist, Tom tossed his smoke on the ground and crushed the butt with the instep of his boot. "I need to make myself feel human again."

Tired and dirty, Tom longed to shed the navy lace-up-at-the-throat sweater that hugged his shoulders. Dust-coated Levi's and chaps encased his legs. His knee-high boots bore the nicks of twigs and pine needles. The stub-bib phase of a beard had lapsed into grubby; and he smelled like campfire smoke, game, and wet dog. He wanted nothing more than to soak in a hot sudsy tub, 'then slip into a fresh set of clothes.

"Making yourself human will have to wait. A lawyer came by twice while you were gone. Last Tuesday he talked with Max, then yesterday I spoke with him." Shay slipped his hand into his pocket, produced a calling card, and read, "Alastair Stykem. You know him?"

"I've never met him, but I know he's got an office on Birch Avenue."

"He's real anxious to talk to you."

"About what?"

Handing Tom the card, Shay shrugged. "Hell if I know. I told him you were expected back today. He pressed me for a time, so I gave him one. You've got a two o'clock appointment at his office."

Tom swore beneath his breath. "What time is it?"

Shay took a watch out of his vest pocket. "Two-ten."

Gazing at Tom, he said, "I figured you'd be in by noon."

"We got that cougar just before lunch, and we had to pack it."

"You'd better get on over there. I'll handle things here."

Tom put a thumb to his hat brim and pushed back then rubbed the grit off his brow. "Stykem didn't tell you what this was all about?"

"No. He just said he needed to talk to you. And that it was important."

Undoing the buckle of his gun belt, Tom looped the leather strap holstering his revolver over the saddle horn; he slung his chaps across the seat.

To the dog, Tom instructed, "Wait," then to Shay he said, "Whatever this is, it'd better not take long."

Leaving the livery behind, Tom walked down Main for a block, giving cursory glances to the post office, Storman's Feed and Fuel, and Buskala's Boarding House. He had become accustomed to the business buildings being brick rather than the wood that was the norm where he and Shay hailed from. Nearly all were two stories and had canvas awnings of various shapes and heights that overhung the high board sidewalks. The corner supported the Blue Flame Saloon. A turn on Birch Avenue and he passed the barbershop, the druggist's, Treber's Men's Clothing store, and the Brooks House Hotel.

He'd rather have been going in the opposite direction so that he could take a look at the warehouse on Old Oak Road. A vacant lot away from the blacksmith's, but at least not across the railroad tracks by the lumberyard and flour mill; stood the building he'd bought from Murphy Magee. The interior measured a good-size, comfortable enough to stock his merchandise and display his trophies and still have plenty of aisle room. For the past few months, he'd spent nearly all his income on sporting goods to fill his store. Tom had been taking men on hunting trips for the better part of a year. The trial period was over. His advertisements in eastern papers had proved to be successful in attracting suit-and-collar types out West for camping adventures they couldn't experience in the big cities.

Tom felt at ease in the woods, but the boisterous antics of dandies grated on him after the first day out. Being isolated with men sporting handlebar mustaches and rifles with superfine sights -- front and rear -- to guarantee a sure shot was not his idea of a challenge. Real gamesmen had to actually work at stalking their prey; not be so out of shape they were unable to hike up hill. Nor would they pine over the loss of forbidden flasks of brandy; Tom allowed no liquor in the campsites.

But now that Shay had arrived, Tom would stay behind in the store, letting the would-be hunters buy as many gadgets as they pleased while his partner took them out on the trail. Tom wasn't opposed to all the newfangled gadgets that helped a man bag his game with relative ease; he just preferred not to use them.

Grasping the handle of a door, Tom let himself inside a lobby that had the faint scent of ink. He crossed the granite floor tiles to a narrow stairwell on his right. At a single hall featured two doors. In gold letters the first had ALASTAIR STYKEM, ATTORNEY AT LAW spelled out. Tom went in the office.

A young woman in a high-buttoned blouse sat behind desk, plucking at keys of a typewriter with one finger. On his intrusion, she looked up and down, then up again; then left and right as if she planned on fleeing. A pair of wire bow spectacles perched on her nose. Black ink smudged her forehead and chin. But it wasn't the ink that made him stare at her -- it was the color of her hair. A vivid red-orange. Like Indian paintbrush petals.

"M-may I h-help you?" she stammered, not meeting his gaze while pushing her glasses farther up her nose. an ink smear across the freckled bridge.

"I have a two-o'clock appointment."

"M-Mr. W-Wolcott?"

His nod went ignored because she refused to lift her head. He had to resort to saying, "Yes."

"Th-they've been waiting for you."

They?

The woman stood, kept her gaze pinned to the carpet's cabbage rose pattern, and took a few steps to the paneled door. Knocking, she stuck her head through the crack she'd opened. "Mr. Wolcott is here," she announced in a clear, smooth voice.

"Good. Send him in." An exasperated breath punctuated the man's next words. "Crescencia, wipe that type-writer ink off your face."

"Yes, Papa."

Crescencia withdrew, then backed toward the desk so Tom couldn't see her face -- as if he hadn't already. Mumbling into the hankie she'd produced from a fold in her skirt, she said, "Y-you may go in, M-Mr. W-Wolcott."

Tom slipped by the desk and nudged the interior door the rest of the way open with his shoulder.

Alastair Stykem sat with his back to the window, sheer curtains deflecting the intensity. of afternoon sun. Upon Tom's entrance, the lawyer rose from behind a massive oak desk and extended his hand. Tom had to step farther into the room to grasp it. After the formality, he felt a presence to his right, and looked down at the occupant in the chair. A pair of pale, mint-colored eyes leveled on him. The woman had rich mahogany hair swept away from her oval face. Huge bows ran around the band of her hat, which sprouted a large, blue chrysanthemum

The lawyer's voice pulled Tom's gaze away. "Mr. Wolcott."

"Stykem," Tom said in acknowledgment.

"You know Miss Huntington?"

Unbidden, Tom's glance once again landed on the seated woman. "I've seen her around." But he had never inquired after her. There was an old-maidish air to the way she carried herself. He would have guessed her to be ten years older than him. But up this close, he could see he'd been mistaken. He had to have had her by at least five.

"Well then, please sit down, Mr. Wolcott."

Tom lowered himself onto one of the plump leather chairs, but he didn't feel at ease in the cushioned depths. Anxiousness made him reach for the half-pack of Richmonds in his front pants pocket, but he stopped himself midway when he saw the disapproval on Miss Huntington's face.

"I see no reason for preamble," Alastair continued. "Miss Huntington has known about the situation for a week, so I'll come right to the point." The lawyer steepled pudgy fingers against his paunch. "Murphy Magee is dead. He fell into a sewer hole last Monday night and sustained fatal injuries."

Tom regarded Alastair quizzically for a moment. Some sixth sense made him proceed with care. "I'm sorry to hear that. Murphy was a regular guy."

"Be that as it may, a problem has arisen that only Mr. Magee could have settled. Since he's not with us, the case has been brought to my attention by the county he recorder's offine in hope that I can mediate a peaceful conclusion to this unfortunate situation."

The words county recorder's office cautioned Tom into silence. Resting his foot on a dusty knee, he pressed his back into the chair and depicted a comfort he didn't feel. Before he'd left Tuesday morning, he'd slipped the receipt Murphy had given him beneath the door to the recorder's office so that he could pick up the deed when he got back into town. Obviously something had gone wrong. Maybe the clerk needed more information. Maybe Murphy hadn't written out the bill of sale correctly. The man had been drunk when they'd made the transaction at the Blue Flame. Even if Murphy had messed up, why was Miss Huntington sitting primly in the chair next to him?

Alastair opened a folder before him and produced two documents. He held them out for Tom to see. "As you can read, the warehouse at 47 Old Oak Road is deeded to both you and Miss Huntington. The clerk had recorded Miss Huntington's title on a Monday afternoon, and yours on a Tuesday morning. For legality's sake, it doesn't really matter whose was recorded first or last. Both are binding. If Mr. Magee was here with us, he could explain how he happened to sell both of you his warehouse. By his taking money twice, he's committed fraud" -- the lawyer gave a slight shrug -- "but who can prosecute a dead man?" After a chuckle, he answered himself. "My late wife would say I would if I could recover something.

Tom saw no humor in that. Accentuating the annoyance he felt with Stykem, Murphy, and Miss Huntington, who had begun to rummage through her purse, Tom brought his foot down hard on the floor and leaned forward. "What are you trying to tell me, Stykem?"

"You and Miss Huntington are both the legal owners of the parcel known as lot four, block two."

A cold knot formed in Tom's gut. Muscles on hisforearms bunched as he took hold of the chair's arms and gripped the padded leather. If Murphy, Magee weren't dead already, he'd go for the man's throat. He should have known better than to do business with a man basted with whiskey. But Tom hadn't wanted to leave for the week without having secured the warehouse, so the transaction had taken place in the saloon.

He heard a dainty cough and sniff, then glared at Miss Huntington. "What do you have to say about this?"

Miss Huntington had brought out a hunk of lacy stuff and lifted the edge to her nostrils. "Mr. Stykem, I find I'm feeling a little light-headed. Could you please open the window for ventilation?"

"Open the window?" Tom echoed. "You've known about this for a week. If anyone is sick, it's me!"

She kept her eyes forward. Curved lashes caught his attention; they were softly fringed and the exact shade of her hair. His gaze lowered. A kind of feathery blue fabric gently outlined her figure, cutting in at her narrow, sashed waist. He knew enough about ladies' fashions to appreciate that she wore pleats, bows, and trims in all the right places. As his eyes lingered on the controlled rise and fall of her breasts as she breathed into her handkerchief, he became aware of what he was doing. With a silent curse, he instantly stopped his appraisal of her.

Tom laid his palms on his thighs. "What now?"

The curtains fell back into place after Alastair unlatched the window lock and lifted the sash. He took his seat and pointedly gazed at the both of them. "Mr. Magee died on the installment plan. Meaning he owed people money." A shuffle of papers, and Stykem came up with a long list that he beganto read from. "Eight dollars and forty-two cents to one Madame Beauchaine of Tut Tut, Louisiana for astrological readings, ten cents to Dutch's Poolroom for dill pickles, three hundred and twenty-two dollars and four cents to the Blue Flame for a bar bill" Alastair waved his hand over the paper and set it down. "Et cetera, et cetera. Frankly, I don't know why he held on to the warehouse as long as he did. He could have used the revenue."

"What are you getting at?" Tom questioned.

"Mr. Magee's estate can't give a refund to either of you. After debtors get hold of what he has left of the money you gave him, there'll barely be enough to cover my fees." Stykem bent his fingers and cracked the knuckles in succession from pinkie to thumb. "I didn't want to suggest this without your being together, but one of you could buy the other out. Of course, that will mean you're paying twice for the property. You'll, have to ask yourself how badly do you want it." Wiry brows arched as he waited for their reaction. Neither of them moved; so the lawyer continued. "Miss Huntington, you pay Mr Wolcott five hundred dollars and the warehouse is yours. Or, Mr. Wolcott, you pay Miss Huntington four hundred and fifty dollars, and the warehouse goes to you."

"Four hundred and fifty?" came an indignant female squeak. "Mr. Stykem, I paid Mr. Magee five hundred dollars for the property."

"Yes, my dear, that is true. But the deal Mr Wolcott worked out with Mr. Magee allowed him to buy the property for fifty dollars less than you paid."

Miss Huntington's rose-colored mouth thinned, and a blush crept up the ivory column of her neck. She was either highly embarrassed or angered to the boiling point. Tom couldn't tell for sure. He didn't really care. All he knew was he didn't have an extra four hundred and fifty dollars with which to buy her out. Nor, couuld he afford for her to pay him five hundred for the right of ownership. No other site could enhance his store the way Magee's's place could.

The warehouse on Old Oak Road was tailor-made for his needs. It was tucked away from the town's populace, and the area surrounding it was semiwooded. A vacant lot sat on either side and to the rear of the building. He'd planned on setting up a target practice area out back, along with extension traps. Since stray clay pigeons and bullets would be no threat to another business or other persons, he didn't need a permit for open firearms other than the formality of an intent notice filed with the police department. He couldn't have that luxury in another building within Harmony's town limits.

"Well, hell," Tom said at length, exhaling. "That buyout idea doesn't work for me."

"Miss Huntington?" Alastair queried.

"My business adviser would caution me against it. My funds are tied up and cannot be released to buy the building a second time." The piece of lace had been lowered onto her lap. She wound a corner of the handkerchief around her slender forefinger, then unwound it. Wind, unwind. Wind, unwind.

"There ought to be some kind of law that says the warehouse is mine," Tom argued.

Miss Huntington cleared her throat. "Excuse me, but I paid for it first. After all, it was recorded to me on a Monday, and you on a Tuesday." Then, ignoring him, she spoke directly to the lawyer. "Mr. Stykem, don't take this the wrong way, but can't we approach a judge who has a higher definition of the law than you? Surely he could settle this as legally as possible."

"I've already consulted with Judge Redvers, in Butte. When it comes to hard cases, he's got a reputation for using common sense as much as law." A toothpick rolled from the edges of Stykem's mountain ofdocuments, and he absently fiddled with it. "Judge Redvers said he'd rule on any action like King Solomon. He'd cut the baby in half."

"We aren't fighting over a baby," Tom grumbled.

"I know that," Stykem cut in. "The baby is a hypothetical. The judge would rule to divide the warehouse, so there's no point in wasting time bringing the case to him when we already know what he'd say."

Miss Huntington's next query held a note of crispness. "So now what?"

"Now we'll have to proceed the only other way." Stykem went to yet another folder and, produced a bid form. "I've taken the liberty of having Mr. Trussel look at the property. For a moderate fee, he can construct a wall that will evenly divide the building. And he can frame in another entry door on the east side. You both would have your own entrances; however, he advised me that the storage room in the rear that runs the length of the building cannot be altered. Several of its posts are supports to the roof and tampering with them could be detrimental to the building's soundness. You would each have your own access to the area, only it wouldn't be sectioned in two like the main interior."

Tom mulled over the possibilities. He'd have to make everything fit in half the space. Perhaps he could still stock the same amount, but the aisles would be cramped. If he had to overload the walkways, where would he put his grizz? The bear had, weighed six hundred pounds before he'd stuffed it. There had to be room for his mammoth eight-point bull elk and the lynx he'd, gotten last winter. He had an endless amount of taxidermic fowl and small rodents that required counter space. Hunters liked to see trophies on display. And Tom had a shitload of them.

Massaging his temple, he fought against the idea of sharing the building with a woman who had a flower on her hat bigger than a moose's butt. He didn't like the thought of having to compromise with her. But it seemed to be the only choice he had.

"Forgive me saying so, Mr. Stykem, but I shouldn't have to pay half."

Tom gave the lawyer no opportunity to respond. "Sure you'll pay half."

Her gaze landed on his. "I shouldn't have to yield another cent." The tuft of lace resumed residency at her nostrils, and she spoke through the weblike pattern. "Already you've gotten your part of the building for fifty dollars less than me."

Alastair cut in. "I'm sorry, Miss Huntington, but the fact of the matter is, it doesn't matter if he paid one penny and you paid one thousand for the place. You both negotiated separate deals that have nothing to do with one another -- except that they're for the same property."

She straightened. "Then my side should be at least a foot wider than his."

"There again, Miss Huntington, you can't measure against the original cost of the building. Both halves will have to be equivalent." A gold signet ring reflected light as Alastair twirled it on his finger. "So, are we all in agreement?"

"I'm afraid you leave us no other choice." Miss Huntington took the words right out of Tom's mouth.

"Mr. Wolcott?"

"It's like the lady said."

"Good, then everything is settled." Stykem tidied the documents on his desk. "It will be up to both of you to inform the postmaster that you'll each be getting your own mail. Miss Huntington, your address will be 47-A Old Oak Road, and Mr. Wolcott, your address will be 47-B Old Oak Road. I'll speak with Mr. Trussel and have him get started with the renovations right away."

Miss Huntington stood, then walked stiffly around the back of her chair to the umbrella stand and retrieved a folded parasol. "Good day, Mr. Stykem."

She'd gone out the door when Tom went to his feet and shoved his left hand in his pocket. "Stykem, I can't say it's been a pleasure."

The lawyer laughed. "I hear that a lot."

Tom stepped into the receiving office, where Miss Huntington and Crescencia were exchanging words. As soon as he came into the room, they shut up. He went past them, Crescencia saying, "G-good day, M-Mr. W-Wolcott."

"Yeah, same to you." He let himself out, thinking he heard Miss Huntington say something like, "Don't you fret about it, dear. You shall overcome, I assure you." Whatever that meant.

Once down on the street level, Tom went for his cigarettes and lit one while he stood on the boardwalk. As he waved out a match, Miss Huntington exited the building. She gave him a quick gaze, then proceeded. He had to go in her direction, so he trailed her. At the corner, they were forced to wait before crossing while the Harmony Fire Department backed its No. 1 engine into the firehouse.

He stood behind her. In height, he had at least ten inches on her, so he had an aerial view of the top of her hat. The air was as fresh as it could get out here, yet she started up with the handkerchief routine again. Then the reason hit him, dragging his pride down a notch. She thought he stunk. Hell, he knew he did. No wonder she'd had Stykem open the window.

On the toes of her proper shoes, Miss Huntington inched her way toward the curb. What did she think he was? A pig? He didn't like to be this in need of a bath, but when had there been time to put on his coattails before delivering himself to her presence?

Now that he realized she was bothered by him, he cut the distance between them. His chest nearly pressed against her shoulder blades. He would have gone in even further if his jaw hadn't been in jeopardy of being rim through by the lethal pin sticking out of her hat.

When she moved again, she went a bit too far and teetered. He grabbed her by the elbow before she could fall into the street.

"What's the matter, Miss Huntington?"

"Nothing." She'd swung her body halfway around so that she could gaze at his face. Exotic green eyes held onto him as physically as his hand held onto her arm. It was a damn shame such pretty eyes belonged to a guardian of morality.

The silkiness of her dress felt, good beneath his fingertips, so he didn't readily release her. Because he'd been so bogged down in his business, it had been a while since he'd held a woman and explored the delights of perfumed skin. He wouldn't have guessed that by touching her elbow he could become aroused. But damn if he wasn't.

What had started out as teasing her was teasing him.

He let her go, then took a deep pull on his cigarette.

"What are you going to do with your side?"

Her voice intruded in his head. Regaining a sense of indifference, he replied, "Sell sporting goods."

Speculation filled her gaze. "Oh..."

He felt obligated -- not that he wasn't curious -- to ask, "What are you going to do with your side?"

"Open a finishing school for ladies."

"What for?"

"To educate them in the rules, usages, and ceremonies of good society."

"You mean to make them like you."

Her chin lifted, and for a minute he thought she might jab him with the point of her unopened parasol. "I should hope."

The boardwalk traffic began to move, but Miss Huntington stayed. "By the way, I hope you aren't allergic." She said the word as if she wished he was. "I'll be bringing my cat."

After giving her an uneven smile, he crossed the street and called over his shoulder, "No problem. I have a dog who loves cats."

Edwina stood on the corner watching Mr. Wolcott disappear from her view. She made a mental list of all his offenses in the presence of her company.

Number one: Not removing his hat.

Number two: Reaching for cigarettes.

Number three. Not practicing personal hygiene.

Number four Openly staring at her without her invitation.

Number five. Using a swear word.

And number six: Verbally insulting her good character.

A half-dozen demerits. She would have counted touching her if his gesture hadn't been somewhat of a valiant attempt to keep her from falling into the street. But then he'd forced her into moving too far off the boardwalk.

Number seven: Unacceptable bodily contact.

In spite of herself, faint tingles rushed to the spot he'd touched. His fingers had been firm yet gentle when he'd held her elbow. Crystal blue eyes had scowled at her beneath down-turned brows. A mane of tawny hair laid in a disarray across unscrupulously- wide shoulders. At first his gaze had been bright with humor, but then it had changed to a dark, unfathomable hue. She didn't want, to think about what he'd been thinking about.

The man was a toad. She had to give today's women the opportunity to choose the right husband for themselves and not settle for whoever lived in Harmony's tight-knit circle. Ironically, Mr. Wolcott had unwittingly been her helper.

She had been aware that he entertained Eastern-gentleman by taking them on hunting jaunts. The steady visits of well-bred clientele had given her an idea this past summer.

Harmony's eligible young ladies should be introduced to men of respectable professions -- not that the selection in town was dire. But those who stayed after graduating the normal school rarely set their sights beyond a trade or working at Kennison's Hardware Emporium. And the handful who had aspirations of bright futures left for college and didn't often return once they saw what the outside world had to offer them.

While in Chicago attending business college, Edwina had fallen in love with a man-about-town. Their relationship had been chocked with spontaneity, but it hadn't resulted in marriage. Smarter now, she realized she lost herself to a beau who heeded his mother's opinions rather than his heart. By enlightening girls about the facets of courtship -- especially the do's and don'ts -- she hoped to empower them to know the difference between real love and passing affections. There were good men who came from large cities, and just because Edwina had chosen the wrong one didn't mean that she thought all Easterners were molly-coddled. On the contrary, those who sought the West for recreation were of a different breed. She saw them as adventure-seekers.

Where Mr. Wolcott had thought of a way to bring gentlemen to their small Montana town, Edwina had thought of a way to show those very gentlemen that charming women didn't necessarily reside only on city streets. Perhaps her students would impress the men into staying, and those marriages could add a diversity to the community.

Edwina crossed the street, then proceeded on Main toward her residence on Sycamore Drive. Sugar maples shaded the walkway, their leaves showing vague signs of the autumn change. The season hadn't taken hold yet. Though nights brought a shivering chill, days could be warm beneath the buttery sunshine.

She had a seven-o'clock meeting that evening at her home. A cake needed to be baked and the silver tea service brought out. Tonight was an important night. Everything had to be perfect. The afternoon had upset her, but at least she'd been apprised of the, situation before Mr. Wolcott had come to the law office.

When she'd first learned about Mr. Magee's selling the warehouse twice, she'd wanted to give him a stern piece of her mind. But immediately thereafter, she'd been informed that he had died in an accident, and she'd felt horrible for having wished he would have one. Only in her mind, he hadn't died... merely suffered some blood loss with a fracture. Or two.

She could hardly bear to think that she'd spent what precious little money she had left in the bank -- just over five hundred dollars -- much less being asked to come up with another five hundred with which to buy out Mr. Wolcott. To add insult to injury, when she found out that she'd paid fifty dollars more than him -- for the exact same property -- she'd felt as if Mr. Magee had made a mockery of womankind. He must have thought females pretty stupid when it came to business deals.

Edwina's lips curved down. Well, she'd been stupid enough, but right now that was a moot point.

Of course she didn't have a business adviser. But after finding out that she'd been made a fool of once, she wasn't about to be one twice. Especially not in front of Mr. Wolcott. He needn't know that she couldn't afford to buy him out.

She wouldn't have had this trouble if she'd taken that quaint suite in the Ellis building. But the deposit and monthly rent would have sent her to the poorhouse even quicker than she was already headed.

Turning down a sycamore-lined street with Queen Anne homes, expansive lawns, and multitudes of color in both trim and landscape, Edwina clicked the tip of her parasol on the hard-packed ground.

Sporting goods. Why did he need to sell that nonsense? The Sears and Roebuck catalogue sold the basics a man needed, and even then, the few items she'd seen while flipping to the ladies' section had looked rather silly.

A mere wall dividing them would surely not be enough. Among other things, his remark that his dog would eat her cat had cinched that. She'd take a waffle iron to that mongrel if it harmed so much as one hair of her precious Honey Tiger's fur.

But for the good of all the marriageable young ladies, Edwina would endure any inconvenience she had to. She longed to see happy homes with loving husbands, celebrating christenings, birthdays, and anniversaries. Of course, that wasn't to be for her...No gentleman would ever marry her if he knew the truth.

So Edwina Huntington had to pretend to be an unapproachable old maid, uninterested in affections. Because she had a deep, dark secret. One that she'd rather take to a presumed spinster's grave than ever -- ever -- reveal.

Copyright © 1997 by Stef Ann Holm