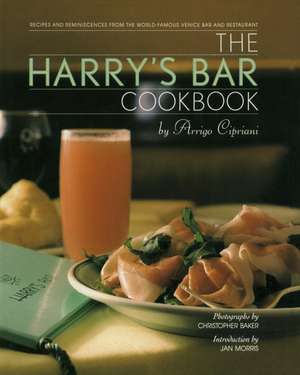

Harry's Bar Cookbook

Autor Arrigo Cipriani, Harry Cipriani Fotografii de Christopher Bakeren Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 sep 1991

Harry’s Bar above all, is a bar. Its distinctive mixed drinks were created by its founder, Arrigo’s father, Giuseppe Cipriani, and they remain the social center of the establishment. Therefore, you’ll find careful instructions for making the world-famous Belini—the frosty, frothy combination of rose-colored peach elixir and Prosecco (the Italian champagne)—and the secret of making the Montgomery, named by Hemingway himself, which is nothing less than the driest, most delicious martini in the world.

Harry’s Bar is also famous for its sandwiches–mouth-watering, overstuffed, unique concoctions: pale yellow egg sandwiches spiked with anchovies; chunks of freshly poached chicken or shrimp bound with creamy, newly made mayonnaise. The Harry’s Bar club sandwich is a legend in itself, knife-and fork food that’s simply superb.

But the bar’s famous risottos and the dozens of pasta dishes—including ravioli, cannelloni, and tagliolini—are the house specialties. Potato gnocchi and simple country food such as polenta, squid, baccala, and beans are transformed into elegant dishes by skillful chefs. Cipriani also invented the sublime dish known as carpaccio and the glorious risotto alla primavera, brilliant ideas that have been imitated all over the world; the original appear here for the first time.

The secret of Harry’s Bar is not only its great drinks and magnificent food, but also its extraordinary atmosphere, in which high spirits pour forth happily. Arrigo Cipriani captures this spirit and tradition, and delivers it all in his own inimitable style. Opinionated and full of surprises, Cipriani ultimately reveals not only the secrets of his kitchen and bar but also the lavish, full color photographs by Christopher Baker make the feast a visual one as well. The Harry’s Bar Cookbook is much more than a cookbook: it’s a enduring experience to be savored and enjoyed.

Preț: 312.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 469

Preț estimativ în valută:

59.85€ • 64.00$ • 49.90£

59.85€ • 64.00$ • 49.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553070309

ISBN-10: 0553070304

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 210 x 264 x 21 mm

Greutate: 1.13 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553070304

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 210 x 264 x 21 mm

Greutate: 1.13 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Harry Cipriani is the son of Giuseppe Cipriani, founder of the original Harry's Bar in Venice. He is also the owner of the New York restaurants, Bellini and Harry Cipriani.

Extras

DRINKS

It's Harry's Bar–we mustn't forget it; it's not Harry's Restaurant. The drinks we serve, the bar itself, the people gathered around it, often in so many layers that they completely block both doorways . . . these are the essence of the place. Dark-lacquered wood, gray marble, Art Deco ashtrays. A large glass bowl of blood oranges. A huge, beautifully shaped glass carafe in which we still make my father's martini: a whole bottle of chilled gin and a little vermouth. Stir and pour into 18 glasses and put them in the freezer. When you serve the martini, this glass frosts like no other.

Sit at the bar and watch the bartender make 24 Bellinis for the party upstairs. Bottle after bottle of cold, rosy peach puree, into the cocktail shaker with bottle after bottle of cold Prosecco. Twenty-four Bellini glasses filled with ice, lined up on a tray. Dump out the ice, pour in the rosy Bellini until the glass is full, with a quarter-inch of foam on top. It's been our most popular drink since my father invented it sometime in the thirties. It didn't have a name until he christened it in honor of the artist for the big Giovanni Bellini exposition in Venice in 1948.

Tending bar is a fine art, and my father was an artist par excellence. He smiled all the time because he was enjoying what he was doing. At the same time he was effortlessly making one perfect drink after another. Here as elsewhere, simplicity was his trademark. He knew that almost everyone who comes into a bar wants one of the most common drinks–there are perhaps 20 of them–and those are the ones he had at his fingertips. Once in a while a customer would ask for something very esoteric or fancy. He would always say, gently and courteously, "Can you tell me how it is made? Then I can make it for you."

The basic drinks are simple and are all variations of five kinds of spirits–gin, vodka, rum, whiskey, and brandy–combined with sparkling water, fruit, vermouth, or liqueurs. Most of the drinks we sell are one or another of these combinations.

But people's tastes do change, and the sales at the bar naturally reflect this. Just as in times of crisis or anxiety people always return to sweet, heavy traditional cooking, so there are moments for certain drinks. Sometimes gin is in; sometimes it's vodka. Some years people like sweet drinks; sometimes they won't touch them. Recently there's been a revival of the classic old sweet liqueurs such as Chartreuse and Cointreau. I can still remember the days when old Mr. Cointreau, well into his eighties, would drink seven or right of his own liqueurs every day.

It's important to keep the atmosphere pleasant in a bar. I think that's easier to do in Italy than in the United States because in the United States people go to bars primarily to drink and perhaps get a little drunk. In Italy it's a social occasion–to have a drink or two and to see people. Of course, once in a while you're having such a good time seeing people that you find yourself getting a little drunk. . . .

But I'm always careful; if anybody drinks too many martinis, I intervene.

My father set a standard for good drinks that we still try to meet. A good drink is very cold and strong enough that you know you're drinking something. I don't like it when bars serve a little splash in a big glass–or when they put in too much ice to make it look like more.

To keep drinks from getting watery, we always use large ice cubes instead of the small ones so many people seem to prefer. Ice machines that make large cubes are not so easy to find, but we insist on it. We keep bottles of gin, vodka, and vermouth in the refrigerator and always chill our glasses.

The proportions of a drink are all-important. We have standard proportions for all our drinks–but we also know how to adjust them to please certain customers.

But I think it's mostly the people–and the atmosphere in the bar–that make our drinks taste so good. People always ask for our drink recipes, and of course I'm giving them to you now, but please don't expect them to transport you to Harry's Bar. You'll have to use a more conventional vehicle for that.

THE BELLINI

Like so many things in "the good old days," making the white peach juice for Bellinis was a lengthy and tedious process. We had a man who did nothing all day but cut up and pit small white peaches and squeeze them with his hands to extract the juice. The juice and pulp were then forced through a chinois–a fine, cone-shaped sieve–to form the rose-colored elixir that is mixed with Prosecco to make Bellinis. Prosecco is the Italian version of champagne and comes from the region around Treviso. The Bellini was a seasonal drink then, available from June through September. Now we are lucky–we can get excellent frozen white peach purée from France and serve Bellinis year-round.

Never use yellow peaches to make a Bellini and never puree the peaches by machine. If you can't find the frozen puree, you'll just have to produce it the old-fashioned way.

Use a food mill or meat grinder to make the pulp and then force it through a fine sieve. If the peach purée is very tart, sweeten it with just a little sugar syrup (see sorbet recipe, page 278). Refrigerate the purée until it is very cold. Mix it with very cold, dry Prosecco in the proportion of 1 part peach puree to 3 parts wine or, for each drink, 1 ounce (30 ml) peach puree and 3 ounces (100 ml) wine. Pour the mixture into well-chilled glasses.

Variations:

A Tiziano is a Bellini made with grape juice instead of peach purée. It is special grape juice made from uva fragola, the same grapes that are used to make strawberry wine, a local specialty that is not even sold in stores. Use 1 part chilled grape juice to 3 parts chilled Prosecco.

A Mimosa is a Bellini using 1 part freshly squeezed orange juice with a little fresh tangerine juice to 3 parts chilled Prosecco. We used to serve it only in the winter, when Bellinis were out of season.

A Rossini is a Bellini using 1 part fresh strawberry purée to 3 parts chilled Prosecco.

GIN DRINKS

There are three famous gin drinks sold at Harry's Bar: one dry, one sweet, and one bitter. Along with the Bellini, they are bottled and sold all over Europe and the United States.

The Montgomery is our dry martini. It was named by Ernest Hemingway in honor of the British general who, he claimed, would fight the enemy only if he had 15 soldiers to their one. That was the proportion of gin to dry vermouth in the martinis Hemingway ordered. At Harry's Bar the proportion we use is actually 10 parts gin to 1 part dry vermouth. The martinis are frozen in their glasses before serving.

A Doge combines 2 parts gin with 1 part sweet vermouth. Carpano is the vermouth we use at Harry's Bar.

The Cardinale is a combination of 6 parts gin to 1 part dry vermouth and 3 parts campari.

WINE

First of all, I think wine should always be decanted into a glass pitcher. However impressive the label is, it can't compare to the pleasure of seeing the actual wine. When you pour the wine into the pitcher and see a little foam, that means the wine is alive.

Then there's the question of glasses. To hold a feather-light octagonal Murano glass in your hand is always a moving experience, but drinking out of it is something else. The same is true of color. If wine is to be tasted in all its full-bodied essence, it needs to be looked at first, naked as a beautiful woman. I don't like glasses that are too big, because they are very often just exercises in virtuosity. Our wineglasses at Harry's Bar are quite small and plain and well balanced–they don't get in the way of one's enjoyment of the wine.

I think people make a bit of a fetish about wine. They worry about drinking the "wrong" wine and are afraid their ignorance will be exposed. I think wine is to be enjoyed with food, and you should drink the wine you like. You can tell when you've found the right wine for you–the more of it you drink, the more you want! You can easily find a good wine to fit any budget–you shouldn't feel you have to choose an expensive wine.

For this reason my father always insisted that we have a good house wine in Harry's Bar. Eighty percent of the wine we sell is the house wine, in glass pitchers. The white is a soave from Verona; the red is a cabernet from Friuli. It's important that the white wines be young, and the reds not more than a couple of seasons old–otherwise the wines will be too heavy and they'll overpower the food, which is basically light.

As with anything else, there are people who have made a special study–a very pleasant one, I should think–of wine. For those people who know what they want and are prepared to pay for it, we have a relatively small, carefully selected list of fine wines. We present the wine list only when someone asks for it–we don't want to force people to order from the wine list. We've suggested Italian and American wines for the dishes we serve, but we also think you can't go wrong with a good red and a good white, your own version of the house wines. I suspect that often the wines from the list are chosen in an effort to impress a guest rather than for their own merits.

Certainly one of my most paralyzing memories is what I now refer to as the champagne affair. Every September one of our regular customers, a very wealthy Italian, would arrive on his yacht for his annual stay in Venice. He was a man in his sixties and, like many Italians, a great Anglophile. One morning he arrived at Harry's Bar with a special bottle of champagne he wanted to serve at a party he was holding that night for some important guests. The champagne was a vintage Krug he had purchased in England–only the nonvintage variety was sold in Italy.

He arrived punctually that evening with his guests. As they sat down at their table, I went over to Ruggero, the bartender, to tell him to take out the bottle of champagne.

"What bottle?" asked Ruggero.

To my horror, I found that the bottle was gone. There had been a dreadful mistake; it had been sold to another customer during the afternoon. And now my wealthy Italian was waving me across the room.

"Cipriani, bring me my special champagne."

I didn't have the courage to tell him the truth. Quickly Ruggero produced a bottle of nonvintage Krug. We wrapped it in a white napkin, and I proceeded to the table carrying a tray of iced glasses, Ruggero following with the champagne. As we approached, I heard the customer saying to his guests, "This is a very special champagne. You will taste the difference."

I poured out the champagne, and as I was about to leave the table he called me back.

"Cipriani. Here, taste it." I cautiously sipped the champagne.

"What do you think?" he asked me seriously.

"Delicious," I whispered.

"What did I tell you?" he said triumphantly. "There is no comparison. This champagne is fantastic."

But still the torture was not over.

"What is the date?" he asked.

I pretended to look underneath the napkin, and remembering the date I had seen on the bottle that morning, I gave him the year.

"Great vintage, great vintage," he chuckled as Ruggero and I hurried to pour out the rest of the champagne and remove the incriminating evidence as fast as we could.

You have to be quick-thinking to run a bar!

APPETIZERS

Contrary to popular opinion, appetizers have nothing to do with stimulating the appetite. In Italy appetizers are called antipasti. The word ante in Latin means "before"–before the meal. But one could also think of it as anti, or against, the meal, and this interpretation could be closer to the truth. So take care: unless the meal is a relatively light one, serve just a little of these tempting dishes.

Talking About Prosciutto

Before the refrigerator people found many ingenious ways to preserve food. Fish, meat, fruits, and vegetables were pickled, smoked, salted, spiced, immersed in oil, and dried. Salt, sugar, vinegar, and spices helped to preserve the food and to enhance its flavor. Often the results were disappointing–the food was safe to eat but unappealing. But occasionally, as in the case of prosciutto, something extraordinary was produced.

Prosciutto is still made by the traditional process of salting a ham and hanging it to dry in the open air for at least a year. Most prosciutto is produced in two areas of Italy–at San Daniele in Friuli and at Langhirano near Parma. Friuli pigs roam hills covered with oak trees and feed mainly on acorns. Parma pigs live in fertile farmland and are fed the whey that is a by-product of Parmesan cheese manufacture. In San Daniele they tell you the prosciutto of San Daniele is sweeter; in Parma they tell you that Parma ham is less salty. When the prosciutto is good, which these days is not all that often, I like both of them. The prosciutto of San Daniele is a little drier and very delicate, while that of Parma has a more decided taste, which I prefer. Parma is the prosciutto we serve at Harry's Bar.

Italian prosciutto is not always available in the United States–you will probably have to go to a store that specializes in Italian products. Most American prosciutto is not as good as imported Italian–it hasn't been aged long enough, and it tends to be very salty. But try the best American prosciutto: Daniel, Volpe, and Citterio. I like Daniel best. But you should taste them before buying and see what you think.

Prosciutto is good by itself, with ruccola, with mozzarella, or with melon, and it is wonderful with sweet, juicy figs, a gift of the autumn along with truffles and wild mushrooms. Prosciutto should be sliced very thin immediately before serving; it is at its best only for about an hour after slicing.

PROSCIUTTO E RUCCOLA

Prosciutto with Arugula

When I first came to the United States, the name arugula struck me as very strange. This peppery Mediterranean green used to grow wild in fields and hedgerows, but is now cultivated. It is called ruccola or rughetta in Italian, and only in pure Sicilian dialect is it called arugula. So I think that if ruccola is now on every good table in the United States, we have to thank the Sicilians, who brought it here for the first time.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

2 to 3 bunches arugula, coarsely chopped (6 cups/1,500 ml)

1/2 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced (225 g)

Wash the arugula very carefully and dry it well. Tear or chop it and mound it on 6 salad plates. Drape the prosciutto over the arugula to cover it completely.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Tocai–Livio Felluga

American: Sauvignon Blanc–B.V.

PROSCIUTTO E MOZZARELLA

Prosciutto with Mozzarella

The best Italian mozzarella comes from the milk of the water buffaloes that graze on the plains near Naples. It's imported to the United States now, but it's expensive. However, fresh homemade mozzarella made from cow's milk is also delicious, and that is what we make at all my restaurants. The problem with making mozzarella at home is that the curd is not easy to obtain. So instead of making it yourself, try to find an Italian delicatessen that makes its own mozzarella. The mozzarella you find in the supermarket must always be avoided–it has a very rubbery consistency and almost no taste.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

1/2 pound mozzarella, cut into 6 equal rounds and then halved (225 g)

1/4 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced (110 g)

Arrange the mozzarella slices on 6 salad plates and drape the prosciutto over them.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Soave–Anselmi

American: Chardonnay–Guenoc Winery

PROSCIUTTO E MELONE

Prosciutto with Melon

Cantaloupes are the melons served in Italy; the best Italian cantaloupes are grown near Modena, not far from the town of Langhirano, where some of the finest Parma ham is cured and aged. And no doubt that is how the marriage first came about.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

1 medium-size ripe cantaloupe, Cranshaw, or honeydew melon

(about 3 pounds/1.350 g)

1/2 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced and cut into wide strips (225 g)

Halve the melon and scoop out the seeds. Cut each half into 6 slices and remove the rind. Place 2 slices of melon on each plate and drape the prosciutto slices over them. Serve immediately.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Pinot Grigio–Lungarotti

American: Chardonnay–Fetzer Vineyards "Reserve"

It's Harry's Bar–we mustn't forget it; it's not Harry's Restaurant. The drinks we serve, the bar itself, the people gathered around it, often in so many layers that they completely block both doorways . . . these are the essence of the place. Dark-lacquered wood, gray marble, Art Deco ashtrays. A large glass bowl of blood oranges. A huge, beautifully shaped glass carafe in which we still make my father's martini: a whole bottle of chilled gin and a little vermouth. Stir and pour into 18 glasses and put them in the freezer. When you serve the martini, this glass frosts like no other.

Sit at the bar and watch the bartender make 24 Bellinis for the party upstairs. Bottle after bottle of cold, rosy peach puree, into the cocktail shaker with bottle after bottle of cold Prosecco. Twenty-four Bellini glasses filled with ice, lined up on a tray. Dump out the ice, pour in the rosy Bellini until the glass is full, with a quarter-inch of foam on top. It's been our most popular drink since my father invented it sometime in the thirties. It didn't have a name until he christened it in honor of the artist for the big Giovanni Bellini exposition in Venice in 1948.

Tending bar is a fine art, and my father was an artist par excellence. He smiled all the time because he was enjoying what he was doing. At the same time he was effortlessly making one perfect drink after another. Here as elsewhere, simplicity was his trademark. He knew that almost everyone who comes into a bar wants one of the most common drinks–there are perhaps 20 of them–and those are the ones he had at his fingertips. Once in a while a customer would ask for something very esoteric or fancy. He would always say, gently and courteously, "Can you tell me how it is made? Then I can make it for you."

The basic drinks are simple and are all variations of five kinds of spirits–gin, vodka, rum, whiskey, and brandy–combined with sparkling water, fruit, vermouth, or liqueurs. Most of the drinks we sell are one or another of these combinations.

But people's tastes do change, and the sales at the bar naturally reflect this. Just as in times of crisis or anxiety people always return to sweet, heavy traditional cooking, so there are moments for certain drinks. Sometimes gin is in; sometimes it's vodka. Some years people like sweet drinks; sometimes they won't touch them. Recently there's been a revival of the classic old sweet liqueurs such as Chartreuse and Cointreau. I can still remember the days when old Mr. Cointreau, well into his eighties, would drink seven or right of his own liqueurs every day.

It's important to keep the atmosphere pleasant in a bar. I think that's easier to do in Italy than in the United States because in the United States people go to bars primarily to drink and perhaps get a little drunk. In Italy it's a social occasion–to have a drink or two and to see people. Of course, once in a while you're having such a good time seeing people that you find yourself getting a little drunk. . . .

But I'm always careful; if anybody drinks too many martinis, I intervene.

My father set a standard for good drinks that we still try to meet. A good drink is very cold and strong enough that you know you're drinking something. I don't like it when bars serve a little splash in a big glass–or when they put in too much ice to make it look like more.

To keep drinks from getting watery, we always use large ice cubes instead of the small ones so many people seem to prefer. Ice machines that make large cubes are not so easy to find, but we insist on it. We keep bottles of gin, vodka, and vermouth in the refrigerator and always chill our glasses.

The proportions of a drink are all-important. We have standard proportions for all our drinks–but we also know how to adjust them to please certain customers.

But I think it's mostly the people–and the atmosphere in the bar–that make our drinks taste so good. People always ask for our drink recipes, and of course I'm giving them to you now, but please don't expect them to transport you to Harry's Bar. You'll have to use a more conventional vehicle for that.

THE BELLINI

Like so many things in "the good old days," making the white peach juice for Bellinis was a lengthy and tedious process. We had a man who did nothing all day but cut up and pit small white peaches and squeeze them with his hands to extract the juice. The juice and pulp were then forced through a chinois–a fine, cone-shaped sieve–to form the rose-colored elixir that is mixed with Prosecco to make Bellinis. Prosecco is the Italian version of champagne and comes from the region around Treviso. The Bellini was a seasonal drink then, available from June through September. Now we are lucky–we can get excellent frozen white peach purée from France and serve Bellinis year-round.

Never use yellow peaches to make a Bellini and never puree the peaches by machine. If you can't find the frozen puree, you'll just have to produce it the old-fashioned way.

Use a food mill or meat grinder to make the pulp and then force it through a fine sieve. If the peach purée is very tart, sweeten it with just a little sugar syrup (see sorbet recipe, page 278). Refrigerate the purée until it is very cold. Mix it with very cold, dry Prosecco in the proportion of 1 part peach puree to 3 parts wine or, for each drink, 1 ounce (30 ml) peach puree and 3 ounces (100 ml) wine. Pour the mixture into well-chilled glasses.

Variations:

A Tiziano is a Bellini made with grape juice instead of peach purée. It is special grape juice made from uva fragola, the same grapes that are used to make strawberry wine, a local specialty that is not even sold in stores. Use 1 part chilled grape juice to 3 parts chilled Prosecco.

A Mimosa is a Bellini using 1 part freshly squeezed orange juice with a little fresh tangerine juice to 3 parts chilled Prosecco. We used to serve it only in the winter, when Bellinis were out of season.

A Rossini is a Bellini using 1 part fresh strawberry purée to 3 parts chilled Prosecco.

GIN DRINKS

There are three famous gin drinks sold at Harry's Bar: one dry, one sweet, and one bitter. Along with the Bellini, they are bottled and sold all over Europe and the United States.

The Montgomery is our dry martini. It was named by Ernest Hemingway in honor of the British general who, he claimed, would fight the enemy only if he had 15 soldiers to their one. That was the proportion of gin to dry vermouth in the martinis Hemingway ordered. At Harry's Bar the proportion we use is actually 10 parts gin to 1 part dry vermouth. The martinis are frozen in their glasses before serving.

A Doge combines 2 parts gin with 1 part sweet vermouth. Carpano is the vermouth we use at Harry's Bar.

The Cardinale is a combination of 6 parts gin to 1 part dry vermouth and 3 parts campari.

WINE

First of all, I think wine should always be decanted into a glass pitcher. However impressive the label is, it can't compare to the pleasure of seeing the actual wine. When you pour the wine into the pitcher and see a little foam, that means the wine is alive.

Then there's the question of glasses. To hold a feather-light octagonal Murano glass in your hand is always a moving experience, but drinking out of it is something else. The same is true of color. If wine is to be tasted in all its full-bodied essence, it needs to be looked at first, naked as a beautiful woman. I don't like glasses that are too big, because they are very often just exercises in virtuosity. Our wineglasses at Harry's Bar are quite small and plain and well balanced–they don't get in the way of one's enjoyment of the wine.

I think people make a bit of a fetish about wine. They worry about drinking the "wrong" wine and are afraid their ignorance will be exposed. I think wine is to be enjoyed with food, and you should drink the wine you like. You can tell when you've found the right wine for you–the more of it you drink, the more you want! You can easily find a good wine to fit any budget–you shouldn't feel you have to choose an expensive wine.

For this reason my father always insisted that we have a good house wine in Harry's Bar. Eighty percent of the wine we sell is the house wine, in glass pitchers. The white is a soave from Verona; the red is a cabernet from Friuli. It's important that the white wines be young, and the reds not more than a couple of seasons old–otherwise the wines will be too heavy and they'll overpower the food, which is basically light.

As with anything else, there are people who have made a special study–a very pleasant one, I should think–of wine. For those people who know what they want and are prepared to pay for it, we have a relatively small, carefully selected list of fine wines. We present the wine list only when someone asks for it–we don't want to force people to order from the wine list. We've suggested Italian and American wines for the dishes we serve, but we also think you can't go wrong with a good red and a good white, your own version of the house wines. I suspect that often the wines from the list are chosen in an effort to impress a guest rather than for their own merits.

Certainly one of my most paralyzing memories is what I now refer to as the champagne affair. Every September one of our regular customers, a very wealthy Italian, would arrive on his yacht for his annual stay in Venice. He was a man in his sixties and, like many Italians, a great Anglophile. One morning he arrived at Harry's Bar with a special bottle of champagne he wanted to serve at a party he was holding that night for some important guests. The champagne was a vintage Krug he had purchased in England–only the nonvintage variety was sold in Italy.

He arrived punctually that evening with his guests. As they sat down at their table, I went over to Ruggero, the bartender, to tell him to take out the bottle of champagne.

"What bottle?" asked Ruggero.

To my horror, I found that the bottle was gone. There had been a dreadful mistake; it had been sold to another customer during the afternoon. And now my wealthy Italian was waving me across the room.

"Cipriani, bring me my special champagne."

I didn't have the courage to tell him the truth. Quickly Ruggero produced a bottle of nonvintage Krug. We wrapped it in a white napkin, and I proceeded to the table carrying a tray of iced glasses, Ruggero following with the champagne. As we approached, I heard the customer saying to his guests, "This is a very special champagne. You will taste the difference."

I poured out the champagne, and as I was about to leave the table he called me back.

"Cipriani. Here, taste it." I cautiously sipped the champagne.

"What do you think?" he asked me seriously.

"Delicious," I whispered.

"What did I tell you?" he said triumphantly. "There is no comparison. This champagne is fantastic."

But still the torture was not over.

"What is the date?" he asked.

I pretended to look underneath the napkin, and remembering the date I had seen on the bottle that morning, I gave him the year.

"Great vintage, great vintage," he chuckled as Ruggero and I hurried to pour out the rest of the champagne and remove the incriminating evidence as fast as we could.

You have to be quick-thinking to run a bar!

APPETIZERS

Contrary to popular opinion, appetizers have nothing to do with stimulating the appetite. In Italy appetizers are called antipasti. The word ante in Latin means "before"–before the meal. But one could also think of it as anti, or against, the meal, and this interpretation could be closer to the truth. So take care: unless the meal is a relatively light one, serve just a little of these tempting dishes.

Talking About Prosciutto

Before the refrigerator people found many ingenious ways to preserve food. Fish, meat, fruits, and vegetables were pickled, smoked, salted, spiced, immersed in oil, and dried. Salt, sugar, vinegar, and spices helped to preserve the food and to enhance its flavor. Often the results were disappointing–the food was safe to eat but unappealing. But occasionally, as in the case of prosciutto, something extraordinary was produced.

Prosciutto is still made by the traditional process of salting a ham and hanging it to dry in the open air for at least a year. Most prosciutto is produced in two areas of Italy–at San Daniele in Friuli and at Langhirano near Parma. Friuli pigs roam hills covered with oak trees and feed mainly on acorns. Parma pigs live in fertile farmland and are fed the whey that is a by-product of Parmesan cheese manufacture. In San Daniele they tell you the prosciutto of San Daniele is sweeter; in Parma they tell you that Parma ham is less salty. When the prosciutto is good, which these days is not all that often, I like both of them. The prosciutto of San Daniele is a little drier and very delicate, while that of Parma has a more decided taste, which I prefer. Parma is the prosciutto we serve at Harry's Bar.

Italian prosciutto is not always available in the United States–you will probably have to go to a store that specializes in Italian products. Most American prosciutto is not as good as imported Italian–it hasn't been aged long enough, and it tends to be very salty. But try the best American prosciutto: Daniel, Volpe, and Citterio. I like Daniel best. But you should taste them before buying and see what you think.

Prosciutto is good by itself, with ruccola, with mozzarella, or with melon, and it is wonderful with sweet, juicy figs, a gift of the autumn along with truffles and wild mushrooms. Prosciutto should be sliced very thin immediately before serving; it is at its best only for about an hour after slicing.

PROSCIUTTO E RUCCOLA

Prosciutto with Arugula

When I first came to the United States, the name arugula struck me as very strange. This peppery Mediterranean green used to grow wild in fields and hedgerows, but is now cultivated. It is called ruccola or rughetta in Italian, and only in pure Sicilian dialect is it called arugula. So I think that if ruccola is now on every good table in the United States, we have to thank the Sicilians, who brought it here for the first time.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

2 to 3 bunches arugula, coarsely chopped (6 cups/1,500 ml)

1/2 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced (225 g)

Wash the arugula very carefully and dry it well. Tear or chop it and mound it on 6 salad plates. Drape the prosciutto over the arugula to cover it completely.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Tocai–Livio Felluga

American: Sauvignon Blanc–B.V.

PROSCIUTTO E MOZZARELLA

Prosciutto with Mozzarella

The best Italian mozzarella comes from the milk of the water buffaloes that graze on the plains near Naples. It's imported to the United States now, but it's expensive. However, fresh homemade mozzarella made from cow's milk is also delicious, and that is what we make at all my restaurants. The problem with making mozzarella at home is that the curd is not easy to obtain. So instead of making it yourself, try to find an Italian delicatessen that makes its own mozzarella. The mozzarella you find in the supermarket must always be avoided–it has a very rubbery consistency and almost no taste.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

1/2 pound mozzarella, cut into 6 equal rounds and then halved (225 g)

1/4 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced (110 g)

Arrange the mozzarella slices on 6 salad plates and drape the prosciutto over them.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Soave–Anselmi

American: Chardonnay–Guenoc Winery

PROSCIUTTO E MELONE

Prosciutto with Melon

Cantaloupes are the melons served in Italy; the best Italian cantaloupes are grown near Modena, not far from the town of Langhirano, where some of the finest Parma ham is cured and aged. And no doubt that is how the marriage first came about.

SERVES 6 AS A FIRST COURSE

1 medium-size ripe cantaloupe, Cranshaw, or honeydew melon

(about 3 pounds/1.350 g)

1/2 pound prosciutto, thinly sliced and cut into wide strips (225 g)

Halve the melon and scoop out the seeds. Cut each half into 6 slices and remove the rind. Place 2 slices of melon on each plate and drape the prosciutto slices over them. Serve immediately.

WINE NOTES

Italian: Pinot Grigio–Lungarotti

American: Chardonnay–Fetzer Vineyards "Reserve"

Descriere

More than 200 recipes--from the world-famous Bellini cocktail to carpaccio to Risotto Primavera--make these first-time-ever-revealed secrets of the legendary restaurant and celebrity watering hole a culinary treasure. 125 color photographs.