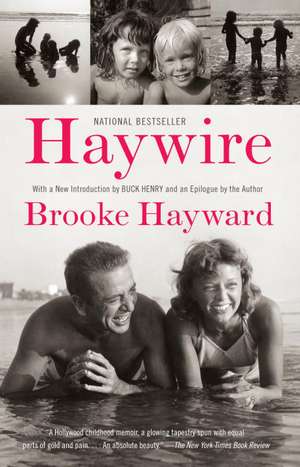

Haywire

Autor Brooke Hayward Buck Henryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2011

Brooke Hayward was born into the most enviable of circumstances. The daughter of a famous actress and a successful Hollywood agent, she was beautiful, wealthy, and living at the very center of the most privileged life America had to offer. Yet at twenty-three her family was ripped apart. Who could have imagined that this magical life could shatter, so conclusively, so destructively? Brooke Hayward tells the riveting story of how her family went haywire.

Preț: 100.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.22€ • 19.85$ • 15.99£

19.22€ • 19.85$ • 15.99£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307739599

ISBN-10: 0307739597

Pagini: 329

Ilustrații: 7 PHOTOS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307739597

Pagini: 329

Ilustrații: 7 PHOTOS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Brooke Hayward lives in New York.

Extras

1

Endings

She had called me late the night before.

Looking back, I recall (or invent?) an urgency to her tone, but really all she'd said was "Can you have breakfast tomorrow?"

"Hmm. What time? Do you have the proper ingredients? English muffins? Marmalade, et cetera?" We'd never shaken the habit of testing one another.

"Of course, you spoiled brat. Come at ten, you shall have ginger marmalade from Bloomingdale's, fresh orange juice I shall squeeze personally, boiled eggs—your customary five and a half minutes. And of course there will be fascinating conversation."

"Might I have a clue?" We'd also become adept at approaching each other with oblique, occasionally fake, courtesy.

Silence, as I'd expected. Then: "Okay, do you have a good gynecologist?"

My silence. "Of course. What for?"

"Brooke, listen." She was suddenly singing. "I have never ever been so happy in my life—I think I'm pregnant."

"What?" I was predictably stunned, but less by that possibility than by her confiding in me. "How the hell did you get pregnant?"

"Oh," she said, giggling, "probably from a toilet seat."

"Bridget. For God's sake, have you gone mad? I mean, how can you possibly be twenty-one years old and reasonably, one hopes, reasonably intelligent and not have been to a—"

"Brooke, listen." She was positively frenzied with elation. "Listen, it's entirely possible that I want to get married, I'm so in love. Do you hear me? Married!"

This conversation was moving just out of my reach, like a smoke ring. All I could say was "Yes. I see what you mean about breakfast—yes, indeed. Might one ask who the expectant father is? No, never mind."

"Ten o'clock tomorrow. What's he like, is he nice, does he hurt?" I knew she meant the gynecologist.

"Yes, no, never mind. Actually he's from India—nice blend of exotic and imperturbable. Forget it, go to sleep."

"Okay, see you in the morning. Farewell." Farewell. Nobody but Bridget ever said goodbye to me like that; all her beginnings and endings where I was concerned were unpredictable, and most of the dialogue in between was enigmatic, a foreign language to any outsider. But for my benefit she talked in her own private shorthand, and what farewell meant was that she wanted me to button up my overcoat and take good care of myself until ten in the morning, because she would miss me in a way that would take far too much sentimental effort to express. I knew what she meant. Often I missed her while we were in the same room together.

I contemplated the phone for some time. Never had I heard her so oddly gay and forthright; as a matter of fact, we hadn't discussed sex since adolescence. Her entire inner life was secretive and mysterious, and no one dared violate it. She sent out powerful "No Trespassing" signals and I had learned to honor them. It crossed my mind that my sister was drunk.

Still, the next morning—a warm October day in 1960—I stood outside her apartment door, nonplussed by the stack of mail and the furled New York Times propped against it. The door itself was slowly getting on my nerves. It didn't open when I rang the doorbell for the fifth or sixth time. It didn't have a crack underneath big enough for a worthwhile view of the interior, although idiotically I'd got down on my hands and knees and looked anyway. Nor did I have a key to unlock it. Even if she had been drunk the night before, which was unlikely—besides, I prided myself on being able to interpret at least her external behavior—she would have been incapable of losing track of her invitation; she was a creature of infuriating compulsion, particularly in matters of time and place, always fussing about my lack of regard for either. Ever since she'd moved from her one-room, third-floor apartment (to which I had possessed a key, much used) to the comparative luxury of an apartment one floor higher with an actual separate bedroom and view (of the building across the street), I'd felt vaguely displaced and surly. For the last year, I'd though of that little one-room apartment as mine, an irrational attachment, since I was not exactly homeless. Until a month before, I'd been living not only in a commodious house in Greenwich, Connecticut, but also, during the week, in a pied-á-terre on East Seventy-second Street. My marriage to Michael Thomas, art historian and budding investment banker, so blithely undertaken during undergraduate days at Vassar and Yale, had, when removed from the insular academic atmosphere of New Haven, fallen apart. We were no longer wrapped in cotton wool; I was no longer a child bride. Now that our divorce was final, I'd moved our two small children into New York and into my own spacious apartment on Central Park West. I continued, however, to drop by Bridget's whenever I had five minutes between modeling jobs and interviews. "Just checking out my make-up," I'd announce breezily, or, "Gotta use your phone." The idea of telling my sister I'd really come to see her would never have crossed my mind.

Her new quarters did have certain advantages: twice the closet space for her warehouses of clothes and shoes, and a fully mirrored bathroom, very handy for looking at oneself from all angles while sitting on the cosmetics-crammed counter and conversing with Bridget submerged in the tub as she tested some new bubble bath. But I had never acquired the same proprietary feelings about this setup. It just didn't have the smell and cozy inconvenience of the old. And now I cursed myself for neglecting to collect the duplicate key she'd had made for me weeks ago. Becoming more and more exasperated with both of us, I rang fiercely four times in a row. Actually I felt like kicking the door. Then I though I heard a sound from where the bedroom ought to be. Of course, it was possible that she might still be asleep. Or, more interesting, asleep with an as yet undisclosed lover. But wouldn't she have left a characteristically humorous note to that effect, right where the bills from Con Ed and Jax were now lying? I began to punch the doorbell to the rhythm of "Yankee Doodle Dandy." During countless afternoon naps when we were young, we'd invented out of boredom what we thought was this highly original game, whereby we would take turns tapping out an unidentified song with our fingernails on the wooden headboards of our twin beds; the object was to determine who was better at guessing it or tapping it, or even choosing it if it was particularly esoteric. We both became fairly skillful, but this time the old signal got no response. I decided that the noise was either imagined or my stomach growling. Fresh orange juice and an English muffin with crisp bacon at Stark's around the corner on Lexington became increasingly crucial. I scribbled her a note and went on down in the elevator, trying to feel philosophical about the whole wasted half-hour. Clearly some matter of extreme urgency was to blame. At this very moment she was certainly racing back to meet me, caught between subways, maybe, wonder of wonders, even springing for a cab.

I galloped across the lobby toward the heavy glass doors and sunlight. Behind the streamlined reception desk, more appropriate to a luxury liner than an apartment building, was a ruddy-faced doorman.

"Hi. Did you see my sister go out today?"

"No, Miss," he answered in a thick brogue, "but then I only come on at eight."

"Ah." I hesitated with a charming smile. "Well. Tell me something." (I tried Mother's ingratiating imperative.) "Um, what time does the mail get delivered? I mean, to the people in the building?"

"Oh, Miss, maybe just over half an hour ago."

"And the newspaper?"

"Oh, somewhere around six or seven. Just a minute, Miss." He moved to the door to let in an elderly couple with a poodle and a Gristede's shopping bag, then bolted the door open so that all the sounds of the morning spewed in. A battle of simultaneous desires was shaping up; whether to go out or stay and satisfy my curiosity. After some consideration I followed him to the immense tropical plant at the entrance. It was embarrassing—even melodramatic—to ask for a key to apartment 403, but I did anyway.

"No problem, Miss. I'll ring Pete and ask him to take you up. He's in the basement."

"No, no, no, thanks, that's too much trouble." Ridiculous. For instance, what if she had had to meet Bill Francisco, a young director at the Yale Drama School (and romantic interest), for whom she was doing some kind of production work? She had probably left a message on my service. A telephone was clearly indicated. Again, Stark's. Besides, Bridget was so intensely ferocious about her privacy there was no telling what she'd do if she knew I'd go to such lengths to break into her sanctuary. Although Bridget was a year and a half younger, I was afraid of her. "Listen, do me a favor—when you see her, tell her I came by and rang but there was no answer and I'll call her later. Okay?"

He nodded and started to lift his hand, but I was already out the door, feeling infinitely better, and striding toward Lexington.

By the time I'd downed my O.J., read the paper, checked Belles for a negative on messages, and gone to the ladies room, the grand superstructure of the day had begun to disintegrate. Out of perverseness, I jumped on the subway and went down to a sound stage on Fourth Street to watch the shooting of Kay Doubleday's big strip scene in Mad Dog Coll, a gangster film that can still, to my embarrassment, be seen occasionally on late-night TV. (It was the first movie I'd ever been in; I had many difficult thing to do, like play the violin and get raped by Vincent [Mad Dog] Coll, played by a young actor named John Chandler, who, on completion of the movie, decided to become a priest.) Kay Doubleday was in my class at Lee Strasberg's; it was in the interest of art, I told myself, to watch her prance down a ramp, singing and stripping her heart out.

I then ate a huge heavy lunch at Moscowitz & Lupowitz with the art director Dick Sylbert. Over coffee, he smoked his pipe and patiently tried to explain the difference between champlevé and cloisonné enamel. This meandered into a discussion of etching techniques. Having killed the afternoon to m thorough satisfaction, I took a slow but up Madison Avenue in order to read Time magazine. It was an absolutely beautiful four o'clock, the best in months, and when the bus got as afar as Fifty-fourth Street, I decided to disembark, fetch Bridget after first giving her hell, and buy a new pair of shoes.

About a block away from her building, a strange thing happened. I was seized by what seemed to be a virulent case of the flu. My temperature rose and fell five degrees in as many seconds. Hot underground springs of scalding perspiration seeped out everywhere, and yet I was shaking with cold, frostbitten inside and out. There was nothing reassuring about the pavement under my feet; I couldn't move forward on it. Well, I thought, by way of helpful explanation, I should be getting home anyway. Besides, after the screw-up this morning she owes me the next move; either this is repressed anger or pre-menstrual tension, but in any case how virtuous and rich I shall feel for not having bought a pair of shoes this afternoon.

I hailed a cab fast, so that I wouldn't have to waste time squatting on Fifty-fourth Street at rush hour with my head between my legs. Ah, well, I thought feverishly, "I grow old . . . I grow old . . . I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled," an ague hath my ham; marrow fatigue, not enough exercise, no tennis, badminton, swimming, fencing, volleyball, modern dance, any dance. I missed school gymnasiums, horseback riding; all I did now was tramp concrete sidewalks and wooden stages and Central Park on weekends. Middle age was phasing out into senility. I fooled the cabdriver, though, by smiling at him so he wouldn't notice all the change I dropped as we pulled up to 15 West Eighty-first Street, across from the Hayden Planetarium. Dark and cool, its dingy Moorish fountained-and-tiled lobby always welcomed me home from the wars. I rose in the elevator, gratefully trying to snuggle against its ancient varnished paneling, and finally stood with ossified feet in the small hall outside my door. The hall was semiprivate; unfortunately it provided wizened old Mrs. Rosenbaum and myself with a common meeting ground, ours being the only two apartments opening off it. She endowed it richly with a perpetual odor of cabbage, and I with an expensive new lay or wallpaper to distract from her barbaric cuisine.

Endings

She had called me late the night before.

Looking back, I recall (or invent?) an urgency to her tone, but really all she'd said was "Can you have breakfast tomorrow?"

"Hmm. What time? Do you have the proper ingredients? English muffins? Marmalade, et cetera?" We'd never shaken the habit of testing one another.

"Of course, you spoiled brat. Come at ten, you shall have ginger marmalade from Bloomingdale's, fresh orange juice I shall squeeze personally, boiled eggs—your customary five and a half minutes. And of course there will be fascinating conversation."

"Might I have a clue?" We'd also become adept at approaching each other with oblique, occasionally fake, courtesy.

Silence, as I'd expected. Then: "Okay, do you have a good gynecologist?"

My silence. "Of course. What for?"

"Brooke, listen." She was suddenly singing. "I have never ever been so happy in my life—I think I'm pregnant."

"What?" I was predictably stunned, but less by that possibility than by her confiding in me. "How the hell did you get pregnant?"

"Oh," she said, giggling, "probably from a toilet seat."

"Bridget. For God's sake, have you gone mad? I mean, how can you possibly be twenty-one years old and reasonably, one hopes, reasonably intelligent and not have been to a—"

"Brooke, listen." She was positively frenzied with elation. "Listen, it's entirely possible that I want to get married, I'm so in love. Do you hear me? Married!"

This conversation was moving just out of my reach, like a smoke ring. All I could say was "Yes. I see what you mean about breakfast—yes, indeed. Might one ask who the expectant father is? No, never mind."

"Ten o'clock tomorrow. What's he like, is he nice, does he hurt?" I knew she meant the gynecologist.

"Yes, no, never mind. Actually he's from India—nice blend of exotic and imperturbable. Forget it, go to sleep."

"Okay, see you in the morning. Farewell." Farewell. Nobody but Bridget ever said goodbye to me like that; all her beginnings and endings where I was concerned were unpredictable, and most of the dialogue in between was enigmatic, a foreign language to any outsider. But for my benefit she talked in her own private shorthand, and what farewell meant was that she wanted me to button up my overcoat and take good care of myself until ten in the morning, because she would miss me in a way that would take far too much sentimental effort to express. I knew what she meant. Often I missed her while we were in the same room together.

I contemplated the phone for some time. Never had I heard her so oddly gay and forthright; as a matter of fact, we hadn't discussed sex since adolescence. Her entire inner life was secretive and mysterious, and no one dared violate it. She sent out powerful "No Trespassing" signals and I had learned to honor them. It crossed my mind that my sister was drunk.

Still, the next morning—a warm October day in 1960—I stood outside her apartment door, nonplussed by the stack of mail and the furled New York Times propped against it. The door itself was slowly getting on my nerves. It didn't open when I rang the doorbell for the fifth or sixth time. It didn't have a crack underneath big enough for a worthwhile view of the interior, although idiotically I'd got down on my hands and knees and looked anyway. Nor did I have a key to unlock it. Even if she had been drunk the night before, which was unlikely—besides, I prided myself on being able to interpret at least her external behavior—she would have been incapable of losing track of her invitation; she was a creature of infuriating compulsion, particularly in matters of time and place, always fussing about my lack of regard for either. Ever since she'd moved from her one-room, third-floor apartment (to which I had possessed a key, much used) to the comparative luxury of an apartment one floor higher with an actual separate bedroom and view (of the building across the street), I'd felt vaguely displaced and surly. For the last year, I'd though of that little one-room apartment as mine, an irrational attachment, since I was not exactly homeless. Until a month before, I'd been living not only in a commodious house in Greenwich, Connecticut, but also, during the week, in a pied-á-terre on East Seventy-second Street. My marriage to Michael Thomas, art historian and budding investment banker, so blithely undertaken during undergraduate days at Vassar and Yale, had, when removed from the insular academic atmosphere of New Haven, fallen apart. We were no longer wrapped in cotton wool; I was no longer a child bride. Now that our divorce was final, I'd moved our two small children into New York and into my own spacious apartment on Central Park West. I continued, however, to drop by Bridget's whenever I had five minutes between modeling jobs and interviews. "Just checking out my make-up," I'd announce breezily, or, "Gotta use your phone." The idea of telling my sister I'd really come to see her would never have crossed my mind.

Her new quarters did have certain advantages: twice the closet space for her warehouses of clothes and shoes, and a fully mirrored bathroom, very handy for looking at oneself from all angles while sitting on the cosmetics-crammed counter and conversing with Bridget submerged in the tub as she tested some new bubble bath. But I had never acquired the same proprietary feelings about this setup. It just didn't have the smell and cozy inconvenience of the old. And now I cursed myself for neglecting to collect the duplicate key she'd had made for me weeks ago. Becoming more and more exasperated with both of us, I rang fiercely four times in a row. Actually I felt like kicking the door. Then I though I heard a sound from where the bedroom ought to be. Of course, it was possible that she might still be asleep. Or, more interesting, asleep with an as yet undisclosed lover. But wouldn't she have left a characteristically humorous note to that effect, right where the bills from Con Ed and Jax were now lying? I began to punch the doorbell to the rhythm of "Yankee Doodle Dandy." During countless afternoon naps when we were young, we'd invented out of boredom what we thought was this highly original game, whereby we would take turns tapping out an unidentified song with our fingernails on the wooden headboards of our twin beds; the object was to determine who was better at guessing it or tapping it, or even choosing it if it was particularly esoteric. We both became fairly skillful, but this time the old signal got no response. I decided that the noise was either imagined or my stomach growling. Fresh orange juice and an English muffin with crisp bacon at Stark's around the corner on Lexington became increasingly crucial. I scribbled her a note and went on down in the elevator, trying to feel philosophical about the whole wasted half-hour. Clearly some matter of extreme urgency was to blame. At this very moment she was certainly racing back to meet me, caught between subways, maybe, wonder of wonders, even springing for a cab.

I galloped across the lobby toward the heavy glass doors and sunlight. Behind the streamlined reception desk, more appropriate to a luxury liner than an apartment building, was a ruddy-faced doorman.

"Hi. Did you see my sister go out today?"

"No, Miss," he answered in a thick brogue, "but then I only come on at eight."

"Ah." I hesitated with a charming smile. "Well. Tell me something." (I tried Mother's ingratiating imperative.) "Um, what time does the mail get delivered? I mean, to the people in the building?"

"Oh, Miss, maybe just over half an hour ago."

"And the newspaper?"

"Oh, somewhere around six or seven. Just a minute, Miss." He moved to the door to let in an elderly couple with a poodle and a Gristede's shopping bag, then bolted the door open so that all the sounds of the morning spewed in. A battle of simultaneous desires was shaping up; whether to go out or stay and satisfy my curiosity. After some consideration I followed him to the immense tropical plant at the entrance. It was embarrassing—even melodramatic—to ask for a key to apartment 403, but I did anyway.

"No problem, Miss. I'll ring Pete and ask him to take you up. He's in the basement."

"No, no, no, thanks, that's too much trouble." Ridiculous. For instance, what if she had had to meet Bill Francisco, a young director at the Yale Drama School (and romantic interest), for whom she was doing some kind of production work? She had probably left a message on my service. A telephone was clearly indicated. Again, Stark's. Besides, Bridget was so intensely ferocious about her privacy there was no telling what she'd do if she knew I'd go to such lengths to break into her sanctuary. Although Bridget was a year and a half younger, I was afraid of her. "Listen, do me a favor—when you see her, tell her I came by and rang but there was no answer and I'll call her later. Okay?"

He nodded and started to lift his hand, but I was already out the door, feeling infinitely better, and striding toward Lexington.

By the time I'd downed my O.J., read the paper, checked Belles for a negative on messages, and gone to the ladies room, the grand superstructure of the day had begun to disintegrate. Out of perverseness, I jumped on the subway and went down to a sound stage on Fourth Street to watch the shooting of Kay Doubleday's big strip scene in Mad Dog Coll, a gangster film that can still, to my embarrassment, be seen occasionally on late-night TV. (It was the first movie I'd ever been in; I had many difficult thing to do, like play the violin and get raped by Vincent [Mad Dog] Coll, played by a young actor named John Chandler, who, on completion of the movie, decided to become a priest.) Kay Doubleday was in my class at Lee Strasberg's; it was in the interest of art, I told myself, to watch her prance down a ramp, singing and stripping her heart out.

I then ate a huge heavy lunch at Moscowitz & Lupowitz with the art director Dick Sylbert. Over coffee, he smoked his pipe and patiently tried to explain the difference between champlevé and cloisonné enamel. This meandered into a discussion of etching techniques. Having killed the afternoon to m thorough satisfaction, I took a slow but up Madison Avenue in order to read Time magazine. It was an absolutely beautiful four o'clock, the best in months, and when the bus got as afar as Fifty-fourth Street, I decided to disembark, fetch Bridget after first giving her hell, and buy a new pair of shoes.

About a block away from her building, a strange thing happened. I was seized by what seemed to be a virulent case of the flu. My temperature rose and fell five degrees in as many seconds. Hot underground springs of scalding perspiration seeped out everywhere, and yet I was shaking with cold, frostbitten inside and out. There was nothing reassuring about the pavement under my feet; I couldn't move forward on it. Well, I thought, by way of helpful explanation, I should be getting home anyway. Besides, after the screw-up this morning she owes me the next move; either this is repressed anger or pre-menstrual tension, but in any case how virtuous and rich I shall feel for not having bought a pair of shoes this afternoon.

I hailed a cab fast, so that I wouldn't have to waste time squatting on Fifty-fourth Street at rush hour with my head between my legs. Ah, well, I thought feverishly, "I grow old . . . I grow old . . . I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled," an ague hath my ham; marrow fatigue, not enough exercise, no tennis, badminton, swimming, fencing, volleyball, modern dance, any dance. I missed school gymnasiums, horseback riding; all I did now was tramp concrete sidewalks and wooden stages and Central Park on weekends. Middle age was phasing out into senility. I fooled the cabdriver, though, by smiling at him so he wouldn't notice all the change I dropped as we pulled up to 15 West Eighty-first Street, across from the Hayden Planetarium. Dark and cool, its dingy Moorish fountained-and-tiled lobby always welcomed me home from the wars. I rose in the elevator, gratefully trying to snuggle against its ancient varnished paneling, and finally stood with ossified feet in the small hall outside my door. The hall was semiprivate; unfortunately it provided wizened old Mrs. Rosenbaum and myself with a common meeting ground, ours being the only two apartments opening off it. She endowed it richly with a perpetual odor of cabbage, and I with an expensive new lay or wallpaper to distract from her barbaric cuisine.

Recenzii

“Haywire is a Hollywood childhood memoir, a glowing tapestry spun with equal parts of gold and pain. . . . An absolute beauty.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Moving and brave and beautifully written. . . . [Hayward] has told it as Fitzgerald might have—with the glow and the glamour, and finally, the heartbreak.” —Newsday

“One of the most extraordinary personal memoirs I've ever read. It has great honesty and charm and humor and beauty, and it is deeply moving.” —Truman Capote

“Exquisite.” —Vanity Fair

“[A] masterpiece in the genre of harrowing autobiographical tell-all.” —W

“Elegant and moving.” —Gore Vidal

“A sort of glorious fable from American mythology. . . . A gripping and eloquent memoir by a courageous and classy writer.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“She has modeled and acted and written: she writes, in fact, marvelously. Haywire mesmerizes. May it cauterize as well.” —The New York Times

“An incredible achievement!” —Lauren Bacall

“One of those rare books which seem to alter your perception of things. It is specific and true in dealing with lives that might have served as models for Fitzgerald’s fiction.” —Mike Nicols

“Brave, honest, intelligent and greatly moving.” —Newsweek

“Engrossing, intimate, moving. . . . Brooke Hayward writes like an angel.” —Cosmopolitan

“Moving and brave and beautifully written. . . . [Hayward] has told it as Fitzgerald might have—with the glow and the glamour, and finally, the heartbreak.” —Newsday

“One of the most extraordinary personal memoirs I've ever read. It has great honesty and charm and humor and beauty, and it is deeply moving.” —Truman Capote

“Exquisite.” —Vanity Fair

“[A] masterpiece in the genre of harrowing autobiographical tell-all.” —W

“Elegant and moving.” —Gore Vidal

“A sort of glorious fable from American mythology. . . . A gripping and eloquent memoir by a courageous and classy writer.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“She has modeled and acted and written: she writes, in fact, marvelously. Haywire mesmerizes. May it cauterize as well.” —The New York Times

“An incredible achievement!” —Lauren Bacall

“One of those rare books which seem to alter your perception of things. It is specific and true in dealing with lives that might have served as models for Fitzgerald’s fiction.” —Mike Nicols

“Brave, honest, intelligent and greatly moving.” —Newsweek

“Engrossing, intimate, moving. . . . Brooke Hayward writes like an angel.” —Cosmopolitan