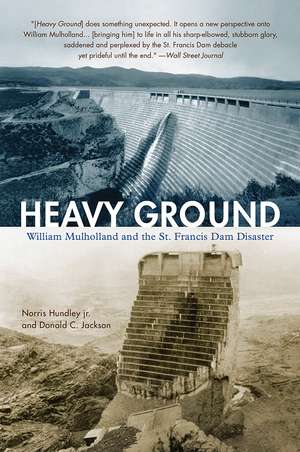

Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster

Autor Norris Hundley, Jr., Donald C. Jacksonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 7 dec 2020 – vârsta ani

Employing copious illustrations and intensive research, Heavy Ground traces the interwoven roles of politics and engineering in explaining how the St. Francis Dam came to be built and the reasons for its collapse. Hundley and Jackson also detail the terror and heartbreak brought by the flood, legal claims against the City of Los Angeles, efforts to restore the Santa Clara Valley, political factors influencing investigations of the failure, and the effect of the disaster on congressional approval of the future Hoover Dam. Underlying it all is a consideration of how the dam—and the disaster—were inextricably intertwined with the life and career of William Mulholland. Ultimately, this thoughtful and nuanced account of the dam’s failure reveals how individual and bureaucratic conceit fed Los Angeles’s desire to control vital water supplies in the booming metropolis of Southern California.

Preț: 427.65 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 641

Preț estimativ în valută:

81.86€ • 88.94$ • 68.80£

81.86€ • 88.94$ • 68.80£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781948908887

ISBN-10: 1948908883

Pagini: 440

Ilustrații: 151 B & W photos, 3 maps, 15 diagrams

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Ediția:Reissue

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

ISBN-10: 1948908883

Pagini: 440

Ilustrații: 151 B & W photos, 3 maps, 15 diagrams

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Ediția:Reissue

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Recenzii

"[Heavy Ground] does something unexpected. It opens a new perspective onto William Mulholland... [bringing him] to life in all his sharp-elbowed, stubborn glory, saddened and perplexed by the St. Francis Dam debacle yet prideful until the end."

—Wall Street Journal

“A meticulously researched… case study of the catastrophic failure north of Los Angeles in March 1928 of the St. Francis Dam that killed 400-450 people… [Heavy Ground] is exemplary for its use of previously unavailable original sources, particularly the L.A. Coroner’s Inquest report.”

—Pacific Historical Review

“A gripping account of this ill-fated dam and the person most directly responsible for its flawed design: William Mulholland.”

—Technology and Culture

"Carefully-crafted, exhaustively-researched, liberally-illustrated, and engagingly-written... an important and welcome addition to the pantheon of scholarship on California Water History."

—Southern California Quarterly

“Above all, [Hundley and Jackson] tell the story of the tragedy itself, the testimonies and recollections of survivors, the arguments over reparations for property damage and lives lost. Forget about Chinatown. This book sets a standard for scholarship that scholars will have to meet in their own research into Los Angeles’ controversial water history.”

—Western Historical Quarterly

“For its lucid explanation of the politics surrounding the [St. Francis] disaster, its minute-by-minute description of the dam’s final moments, and ensuing tidal wave that murderously swept down the valley, and its meticulous and careful analysis of the dam’s design, construction, and failure, Heavy Ground joins the list of [Hacker Prize] books displaying “exceptional scholarship” while reaching for readers “beyond the academy.” Additionally, the book superbly integrates the history of technology with social, cultural, and economic contexts.”

—Sally Hacker Prize citation

—Wall Street Journal

“A meticulously researched… case study of the catastrophic failure north of Los Angeles in March 1928 of the St. Francis Dam that killed 400-450 people… [Heavy Ground] is exemplary for its use of previously unavailable original sources, particularly the L.A. Coroner’s Inquest report.”

—Pacific Historical Review

“A gripping account of this ill-fated dam and the person most directly responsible for its flawed design: William Mulholland.”

—Technology and Culture

"Carefully-crafted, exhaustively-researched, liberally-illustrated, and engagingly-written... an important and welcome addition to the pantheon of scholarship on California Water History."

—Southern California Quarterly

“Above all, [Hundley and Jackson] tell the story of the tragedy itself, the testimonies and recollections of survivors, the arguments over reparations for property damage and lives lost. Forget about Chinatown. This book sets a standard for scholarship that scholars will have to meet in their own research into Los Angeles’ controversial water history.”

—Western Historical Quarterly

“For its lucid explanation of the politics surrounding the [St. Francis] disaster, its minute-by-minute description of the dam’s final moments, and ensuing tidal wave that murderously swept down the valley, and its meticulous and careful analysis of the dam’s design, construction, and failure, Heavy Ground joins the list of [Hacker Prize] books displaying “exceptional scholarship” while reaching for readers “beyond the academy.” Additionally, the book superbly integrates the history of technology with social, cultural, and economic contexts.”

—Sally Hacker Prize citation

Notă biografică

Norris Hundley (1935–2013) was an author and leader in the history of the American West and in the nascent field of water history. He was a was long time member of the History Department at UCLA and served as president of both the Western History Association and the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association.

Donald C. Jackson is the Cornelia F. Hugel Professor of History at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. He has authored many books and articles on the history of dams and hydraulic engineering.

Donald C. Jackson is the Cornelia F. Hugel Professor of History at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. He has authored many books and articles on the history of dams and hydraulic engineering.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

Mulholland: A Man and an Aqueduct

One of many sad truths about the St. Francis Dam disaster is that residents of the Santa Clara Valley—the people who bore the brunt of suffering and death—played essentially no role in the Conception or operation of the dam. Th e vast bulk of the floodwater was artificially fed into the Santa Clara River watershed with no intention that it would ever benefit citizens of the valley. True, some water in the reservoir originated within the thirty-seven square miles of foothills lying above the dam, but far more fell to earth as rain and snow 200 miles to the north, along the lofty eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada. This imported water entered San Francisquito Creek through an astounding feat of human ingenuity and technological bravado, underwritten by individuals with little interest in the people or prosperity of the Santa Clara Valley. To them, the valley was a mere corridor and way station for

an aqueduct carrying water to Los Angeles.

The use of San Francisquito Canyon for a major reservoir was largely an accident of history, a by-product of decisions and initiatives undertaken by Los Angeles officials over a period of twenty years. St. Francis

The dam was but one component of a much larger project—the Los Angeles Aqueduct—designed to slake the thirst and light the homes of the rapidly growing city. Stretching over 230 miles from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley, the Los Angeles Aqueduct still holds great prominence in the public mind because of its role in defining the political economy of Southern California’s premier city. To appreciate how the St. Francis Dam came to be built requires an understanding of both the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the man most responsible for its construction.

As the aqueduct’s chief engineer and its public face, William Mulholland stood as a colossus over early twentieth-century Los Angeles.

Diverting the flow of the Owens River across desert wasteland and through mountain escarpment, the aqueduct created the hydraulic Foundation of a world-class city. By bringing copious quantities of fresh water to the arid coastal plain, Mulholland led the way to long-term survival and prosperity for the citizenry of a rapidly growing Los Angeles. Of course, for people living outside the city—especially the farmers in the Owens and Santa Clara river valleys—his attitude could appear imperious and even abusive. But to those in his adopted home city, and to many who held no particular stake in Southern California water quarrels, his efforts stood as a paragon of technological achievement and progressive efficiency.

The Ladder of Authority

William Mulholland’s prominence and renown sprang from inauspicious beginnings. Born in Ireland in 1855, he joined the British merchant marine in the late 1860s but, after four years as a sailor before the mast, he recognized that a mariner’s life “would get him nowhere in a material way.” Coming ashore in New York City in 1874 he headed west to work on a Great Lakes steamer and in a Michigan logging camp. Joined by his brother Hugh, he moved to Pittsburgh to work for an uncle at a dry goods emporium. When two of his uncle’s children died of tuberculosis, the extended family left for California in late 1876, seeking a more salutary

climate. Passage across the Isthmus of Panama and a horseback trip from San Francisco brought Mulholland to Los Angeles in January 1877.3

Apparently unimpressed by Southern California, Mulholland headed for the port of San Pedro to ship out. Along the way he met Manuel Dominguez, grandson of the original owner of Rancho San Pedro, who offered him a job drilling artesian wells near the town of Compton, a few miles south of downtown Los Angeles. Mulholland accepted and, while working his first well, discovered fossil remains that, he later claimed, “changed the whole course of my life...These things fired my curiosity. I wanted to know how they got there and so I got hold of Joseph Le Conte’s book on the geology of this country. Right there I decided to become an engineer.”4

For whatever reason, he did not immediately act upon this apparent epiphany. Instead, he trekked to Arizona Territory in search of gold. But riches proved elusive, and Army troops warned of hostile Apaches. Concluding that “presence of mind was best secured by absence of body,” he returned to Los Angeles by the spring of 1877. Once back, he joined a ditch gang as a laborer for the Los Angeles City Water Company. Following from his aspiration to become an engineer, his unlikely employment as a lowly ditch digger nonetheless proved to be a major turning point both in his life and in the city’s history.5

As in many towns and cities in nineteenth-century America, Los Angeles leaders looked to private capital to finance a municipal water supply system. After some faltering short-lived arrangements, in 1868 the city entered into what appeared a more promising agreement. For the privilege of building and operating a complex of pumps, pipes, valves, ditches, and small distribution reservoirs, the Los Angeles City Water Company paid the city 1,500 a year (soon reduced to 400 in exchange for building a plaza fountain). In return the company received a thirty-year lease protecting it from competition and allowing it to charge residents a usage fee set by the city, the key restriction being that the fee could never fall below what was authorized in 1868. To safeguard the city’s claims to water in the Los Angeles River (the so-called pueblo right), the lease prohibited the company from taking more than ten miner’s inches directly from the river. (As calculated in Southern California, fifty miner’s inches equals a flow of one cubic foot per second, so ten miner’s inches is an exceedingly small amount.) The assumption

was that additional water needed by the company would be taken from Crystal Springs, a swampy tract near the river with a high water table.6

Mulholland’s future employers determined that ten miner’s inches, even when combined with water from Crystal Springs, fell far short of what they needed to prosper. To protect itself, the company secretly drove a tunnel into the riverbed capable of drawing upwards of 1,500 miner’s inches—150 times more than authorized by the lease. Several years passed before the ploy became public and, as Vincent Ostrom has noted, “the city was at a loss as to what to do about it.” To shut down the company would be to shut off the city’s domestic water supply. City leaders and residents seethed, all the more when they discovered another unsavory gambit: the company had created a subsidiary corporation that claimed a right to the Los Angeles River on grounds that, as a separate entity, it was not bound by the lease. With growing anger, the city fought these and similar subterfuges, winning some battles and losing others. For its part, the company resisted public scrutiny of its corporate affairs and valued employees who protected this insularity.7

In a story later recounted by Mulholland’s colleagues, his early tenure with the water company found its defining moment in an unanticipated confrontation with its president, William Perry. Riding by a zanja (ditch) where the new employee was clearing debris, Perry noticed the single-minded attention Mulholland brought to his job. Asked what he was doing, the future chief engineer kept his head down and growled: “It’s none of your damned business!” Perry backed off, but he liked what he saw in Mulholland’s attitude and soon promoted him to foreman.

While perhaps apocryphal, the anecdote underscores the distinctive relationship forged between Mulholland and the water company. It also highlights two fundamental attributes at the core of Mulholland’s professional character: a willingness to work hard in the service of his employers and a disposition to resist (perhaps even resent) outside review of his work. The latter would prove particularly significant when it came time to build the St. Francis Dam.8

Over the next several years, Mulholland’s field promotion to foreman was followed by steady professional advancement. Th e first significant step up the ladder came in 1880 when he took charge of a major pipe- laying project in the Buena Vista district near downtown. This move also brought him close to the city’s public library, where he embarked on a journey of self-education. He voraciously read texts on civil engineering, hydraulics, geology, and mathematics, as well as Shakespeare, Pope, Carlyle, and other classics, and later famously exclaimed, “Damn a man who doesn’t read books...Th e test of a man’s mind is his knowledge of humanity, of the politics of human life, his comprehension of the things that move men.” This hunger for self-education was motivated by a lack of schooling. Unlike many civil and hydraulic engineers who later worked with him and attained prominence in the early twentieth century—including his colleagues Arthur P. Davis, John R. Freeman, and J. B. Lippincott—Mulholland was essentially self-taught. His hydraulic engineering knowledge derived from a reading of technical books and articles combined with extensive on-the-job experience. To bring it all together, he relied upon a quick mind and a remarkable memory.9

At Buena Vista, Mulholland honed his skills by overseeing expansion of the pipeline and reservoir and, two years later, by supervising a large crew in building a major flume and ditch. After a brief sojourn in 1884 when he and his brother visited the state of Washington “to study

rivers” and an equally brief stint as an independent contractor working on city construction projects, he returned to work for Perry and the private water company. In 1885, Perry sent him to Ventura County to help build an irrigation system for the town of Fillmore. In itself this assignment was not particularly noteworthy, but the job brought him into the Santa Clara Valley. If in his off hours he took time to investigate the upper reaches of the watershed, he may have made his first visit to San Francisquito Canyon and the future site of the St. Francis Dam.10

When the Fillmore job ended, he returned to Los Angeles to supervise flume- and tunnel-building at Crystal Springs. By this time, Mulholland’s technical knowledge and his acumen in managing workers were much appreciated by company officials. Thus, when the superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Company died suddenly in November 1886, the way opened for advancement. A younger employee serving as assistant superintendent allegedly declined to step up, averring that Mulholland was better qualified for the post. Perry agreed, and the one-time ditch digger was promoted to superintendent of the city’s water works. A mere decade had passed since he first set foot in Los Angeles.11

When Mulholland started his new job, Southern California was exulting in a major land boom. Ignited by the Santa Fe Railway’s arrival in late 1885, which offered competition to the Southern Pacific, the real estate frenzy was stoked by cheap transcontinental fares. Easterners swarmed into the region, and within three years the population of Los Angeles more than quadrupled, from 11,000 to 50,000. The newcomers, as well as local boosters and real estate developers, expected a reliable water supply in their newfound Eden. Mulholland met the challenge by replacing antiquated water mains and extending water pipes to new neighborhoods and commercial districts. When torrential rains hit hard during the winter of 1889–90, the Los Angeles River threatened to jump its banks and knock out the water system. Working long shifts, Mulholland and his devoted crew kept the system from collapse. As a reward, the water company bestowed upon him a gold watch—material evidence of his value to the shareholders.12

Through the 1890s, Mulholland’s stature continued to grow, but changes loomed as the water company’s thirty-year franchise neared expiration. As in many other cities in the United States during the Progressive Era, a powerful political reform movement had emerged in Los Angeles. A key reform sought by civic leaders focused on restoring municipal control over the water system. Perry and the water company resisted divestiture by eminent domain and, for several years, delayed municipal takeover. Nonetheless, the tide finally turned and, in 1902, the water system came under direct city control. At this juncture, Mulholland could have remained with the company’s owners and pursued other water projects financed by their capital, but he was loath to relinquish control over the system he had worked so hard to create. Steadfastly loyal to the water company while in its camp, he now transferred his allegiance to the city of Los Angeles.13

For the city’s political leaders there were practical reasons to welcome Mulholland into municipal employment. Paramount among them was the knowledge he brought to his job. When the city bought the Los Angeles City Water Company, detailed design and construction records were not always available. Mulholland compensated for the gaps by having memorized many features of the complex distribution system. When challenged during the purchase negotiations, Mulholland reportedly called for a map and identified details about pipes

throughout the city. Th is only prompted new challenges. Mulholland responded with a call for excavations that, when carried out, corroborated his testimony. This show of bravado—perhaps embellished in later retellings—helped ensure his continuation as superintendent

after the municipal takeover. Knowledge often translates into power and, as he later wryly commented, “the city bought the works and me

with it.”14

From the beginning of his tenure as municipal superintendent in 1902, Mulholland held the respect—if not the absolute deference—of his nominal superiors. Over the years he reported to a series of supervisory groups whose names and responsibilities may have changed, but whose managerial authority derived from the Los Angeles City Charter. Following acquisition of the water system, the Board of Water Commissioners became his first boss; then in 1911 the Board of Public Service Commissioners succeeded to that role; fourteen years later—while construction of the St. Francis Dam was underway—authority passed yet again, this time to the newly formed Board of Water and Power Commissioners.15

No matter who was nominally in charge, or how they were designated, from 1902 through 1928 Mulholland exercised almost unfettered control over the city’s network of water supply and distribution.

Once in charge of the public water system, Mulholland moved rapidly to make improvements and take on new initiatives. In concert with reduced water rates, he installed meters as a way to precisely record use and encourage conservation. Within two years water consumption had fallen by a third and, despite nominally lower rates, the proliferation of meters actually raised revenue. This income allowed him to rebuild much of the water system in his first three years on the city payroll. With the water system turning a profit (some 1.5 million in four years), he expanded the pumping capacity at Buena Vista, built Solano Reservoir, and purchased the West Los Angeles Water Company (a remnant of the former Los Angeles City Water Company). Public acclaim for these accomplishments set the stage for a sympathetic response when he announced plans for a major new source of municipal water supply.

Mulholland: A Man and an Aqueduct

One of many sad truths about the St. Francis Dam disaster is that residents of the Santa Clara Valley—the people who bore the brunt of suffering and death—played essentially no role in the Conception or operation of the dam. Th e vast bulk of the floodwater was artificially fed into the Santa Clara River watershed with no intention that it would ever benefit citizens of the valley. True, some water in the reservoir originated within the thirty-seven square miles of foothills lying above the dam, but far more fell to earth as rain and snow 200 miles to the north, along the lofty eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada. This imported water entered San Francisquito Creek through an astounding feat of human ingenuity and technological bravado, underwritten by individuals with little interest in the people or prosperity of the Santa Clara Valley. To them, the valley was a mere corridor and way station for

an aqueduct carrying water to Los Angeles.

The use of San Francisquito Canyon for a major reservoir was largely an accident of history, a by-product of decisions and initiatives undertaken by Los Angeles officials over a period of twenty years. St. Francis

The dam was but one component of a much larger project—the Los Angeles Aqueduct—designed to slake the thirst and light the homes of the rapidly growing city. Stretching over 230 miles from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley, the Los Angeles Aqueduct still holds great prominence in the public mind because of its role in defining the political economy of Southern California’s premier city. To appreciate how the St. Francis Dam came to be built requires an understanding of both the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the man most responsible for its construction.

As the aqueduct’s chief engineer and its public face, William Mulholland stood as a colossus over early twentieth-century Los Angeles.

Diverting the flow of the Owens River across desert wasteland and through mountain escarpment, the aqueduct created the hydraulic Foundation of a world-class city. By bringing copious quantities of fresh water to the arid coastal plain, Mulholland led the way to long-term survival and prosperity for the citizenry of a rapidly growing Los Angeles. Of course, for people living outside the city—especially the farmers in the Owens and Santa Clara river valleys—his attitude could appear imperious and even abusive. But to those in his adopted home city, and to many who held no particular stake in Southern California water quarrels, his efforts stood as a paragon of technological achievement and progressive efficiency.

The Ladder of Authority

William Mulholland’s prominence and renown sprang from inauspicious beginnings. Born in Ireland in 1855, he joined the British merchant marine in the late 1860s but, after four years as a sailor before the mast, he recognized that a mariner’s life “would get him nowhere in a material way.” Coming ashore in New York City in 1874 he headed west to work on a Great Lakes steamer and in a Michigan logging camp. Joined by his brother Hugh, he moved to Pittsburgh to work for an uncle at a dry goods emporium. When two of his uncle’s children died of tuberculosis, the extended family left for California in late 1876, seeking a more salutary

climate. Passage across the Isthmus of Panama and a horseback trip from San Francisco brought Mulholland to Los Angeles in January 1877.3

Apparently unimpressed by Southern California, Mulholland headed for the port of San Pedro to ship out. Along the way he met Manuel Dominguez, grandson of the original owner of Rancho San Pedro, who offered him a job drilling artesian wells near the town of Compton, a few miles south of downtown Los Angeles. Mulholland accepted and, while working his first well, discovered fossil remains that, he later claimed, “changed the whole course of my life...These things fired my curiosity. I wanted to know how they got there and so I got hold of Joseph Le Conte’s book on the geology of this country. Right there I decided to become an engineer.”4

For whatever reason, he did not immediately act upon this apparent epiphany. Instead, he trekked to Arizona Territory in search of gold. But riches proved elusive, and Army troops warned of hostile Apaches. Concluding that “presence of mind was best secured by absence of body,” he returned to Los Angeles by the spring of 1877. Once back, he joined a ditch gang as a laborer for the Los Angeles City Water Company. Following from his aspiration to become an engineer, his unlikely employment as a lowly ditch digger nonetheless proved to be a major turning point both in his life and in the city’s history.5

As in many towns and cities in nineteenth-century America, Los Angeles leaders looked to private capital to finance a municipal water supply system. After some faltering short-lived arrangements, in 1868 the city entered into what appeared a more promising agreement. For the privilege of building and operating a complex of pumps, pipes, valves, ditches, and small distribution reservoirs, the Los Angeles City Water Company paid the city 1,500 a year (soon reduced to 400 in exchange for building a plaza fountain). In return the company received a thirty-year lease protecting it from competition and allowing it to charge residents a usage fee set by the city, the key restriction being that the fee could never fall below what was authorized in 1868. To safeguard the city’s claims to water in the Los Angeles River (the so-called pueblo right), the lease prohibited the company from taking more than ten miner’s inches directly from the river. (As calculated in Southern California, fifty miner’s inches equals a flow of one cubic foot per second, so ten miner’s inches is an exceedingly small amount.) The assumption

was that additional water needed by the company would be taken from Crystal Springs, a swampy tract near the river with a high water table.6

Mulholland’s future employers determined that ten miner’s inches, even when combined with water from Crystal Springs, fell far short of what they needed to prosper. To protect itself, the company secretly drove a tunnel into the riverbed capable of drawing upwards of 1,500 miner’s inches—150 times more than authorized by the lease. Several years passed before the ploy became public and, as Vincent Ostrom has noted, “the city was at a loss as to what to do about it.” To shut down the company would be to shut off the city’s domestic water supply. City leaders and residents seethed, all the more when they discovered another unsavory gambit: the company had created a subsidiary corporation that claimed a right to the Los Angeles River on grounds that, as a separate entity, it was not bound by the lease. With growing anger, the city fought these and similar subterfuges, winning some battles and losing others. For its part, the company resisted public scrutiny of its corporate affairs and valued employees who protected this insularity.7

In a story later recounted by Mulholland’s colleagues, his early tenure with the water company found its defining moment in an unanticipated confrontation with its president, William Perry. Riding by a zanja (ditch) where the new employee was clearing debris, Perry noticed the single-minded attention Mulholland brought to his job. Asked what he was doing, the future chief engineer kept his head down and growled: “It’s none of your damned business!” Perry backed off, but he liked what he saw in Mulholland’s attitude and soon promoted him to foreman.

While perhaps apocryphal, the anecdote underscores the distinctive relationship forged between Mulholland and the water company. It also highlights two fundamental attributes at the core of Mulholland’s professional character: a willingness to work hard in the service of his employers and a disposition to resist (perhaps even resent) outside review of his work. The latter would prove particularly significant when it came time to build the St. Francis Dam.8

Over the next several years, Mulholland’s field promotion to foreman was followed by steady professional advancement. Th e first significant step up the ladder came in 1880 when he took charge of a major pipe- laying project in the Buena Vista district near downtown. This move also brought him close to the city’s public library, where he embarked on a journey of self-education. He voraciously read texts on civil engineering, hydraulics, geology, and mathematics, as well as Shakespeare, Pope, Carlyle, and other classics, and later famously exclaimed, “Damn a man who doesn’t read books...Th e test of a man’s mind is his knowledge of humanity, of the politics of human life, his comprehension of the things that move men.” This hunger for self-education was motivated by a lack of schooling. Unlike many civil and hydraulic engineers who later worked with him and attained prominence in the early twentieth century—including his colleagues Arthur P. Davis, John R. Freeman, and J. B. Lippincott—Mulholland was essentially self-taught. His hydraulic engineering knowledge derived from a reading of technical books and articles combined with extensive on-the-job experience. To bring it all together, he relied upon a quick mind and a remarkable memory.9

At Buena Vista, Mulholland honed his skills by overseeing expansion of the pipeline and reservoir and, two years later, by supervising a large crew in building a major flume and ditch. After a brief sojourn in 1884 when he and his brother visited the state of Washington “to study

rivers” and an equally brief stint as an independent contractor working on city construction projects, he returned to work for Perry and the private water company. In 1885, Perry sent him to Ventura County to help build an irrigation system for the town of Fillmore. In itself this assignment was not particularly noteworthy, but the job brought him into the Santa Clara Valley. If in his off hours he took time to investigate the upper reaches of the watershed, he may have made his first visit to San Francisquito Canyon and the future site of the St. Francis Dam.10

When the Fillmore job ended, he returned to Los Angeles to supervise flume- and tunnel-building at Crystal Springs. By this time, Mulholland’s technical knowledge and his acumen in managing workers were much appreciated by company officials. Thus, when the superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Company died suddenly in November 1886, the way opened for advancement. A younger employee serving as assistant superintendent allegedly declined to step up, averring that Mulholland was better qualified for the post. Perry agreed, and the one-time ditch digger was promoted to superintendent of the city’s water works. A mere decade had passed since he first set foot in Los Angeles.11

When Mulholland started his new job, Southern California was exulting in a major land boom. Ignited by the Santa Fe Railway’s arrival in late 1885, which offered competition to the Southern Pacific, the real estate frenzy was stoked by cheap transcontinental fares. Easterners swarmed into the region, and within three years the population of Los Angeles more than quadrupled, from 11,000 to 50,000. The newcomers, as well as local boosters and real estate developers, expected a reliable water supply in their newfound Eden. Mulholland met the challenge by replacing antiquated water mains and extending water pipes to new neighborhoods and commercial districts. When torrential rains hit hard during the winter of 1889–90, the Los Angeles River threatened to jump its banks and knock out the water system. Working long shifts, Mulholland and his devoted crew kept the system from collapse. As a reward, the water company bestowed upon him a gold watch—material evidence of his value to the shareholders.12

Through the 1890s, Mulholland’s stature continued to grow, but changes loomed as the water company’s thirty-year franchise neared expiration. As in many other cities in the United States during the Progressive Era, a powerful political reform movement had emerged in Los Angeles. A key reform sought by civic leaders focused on restoring municipal control over the water system. Perry and the water company resisted divestiture by eminent domain and, for several years, delayed municipal takeover. Nonetheless, the tide finally turned and, in 1902, the water system came under direct city control. At this juncture, Mulholland could have remained with the company’s owners and pursued other water projects financed by their capital, but he was loath to relinquish control over the system he had worked so hard to create. Steadfastly loyal to the water company while in its camp, he now transferred his allegiance to the city of Los Angeles.13

For the city’s political leaders there were practical reasons to welcome Mulholland into municipal employment. Paramount among them was the knowledge he brought to his job. When the city bought the Los Angeles City Water Company, detailed design and construction records were not always available. Mulholland compensated for the gaps by having memorized many features of the complex distribution system. When challenged during the purchase negotiations, Mulholland reportedly called for a map and identified details about pipes

throughout the city. Th is only prompted new challenges. Mulholland responded with a call for excavations that, when carried out, corroborated his testimony. This show of bravado—perhaps embellished in later retellings—helped ensure his continuation as superintendent

after the municipal takeover. Knowledge often translates into power and, as he later wryly commented, “the city bought the works and me

with it.”14

From the beginning of his tenure as municipal superintendent in 1902, Mulholland held the respect—if not the absolute deference—of his nominal superiors. Over the years he reported to a series of supervisory groups whose names and responsibilities may have changed, but whose managerial authority derived from the Los Angeles City Charter. Following acquisition of the water system, the Board of Water Commissioners became his first boss; then in 1911 the Board of Public Service Commissioners succeeded to that role; fourteen years later—while construction of the St. Francis Dam was underway—authority passed yet again, this time to the newly formed Board of Water and Power Commissioners.15

No matter who was nominally in charge, or how they were designated, from 1902 through 1928 Mulholland exercised almost unfettered control over the city’s network of water supply and distribution.

Once in charge of the public water system, Mulholland moved rapidly to make improvements and take on new initiatives. In concert with reduced water rates, he installed meters as a way to precisely record use and encourage conservation. Within two years water consumption had fallen by a third and, despite nominally lower rates, the proliferation of meters actually raised revenue. This income allowed him to rebuild much of the water system in his first three years on the city payroll. With the water system turning a profit (some 1.5 million in four years), he expanded the pumping capacity at Buena Vista, built Solano Reservoir, and purchased the West Los Angeles Water Company (a remnant of the former Los Angeles City Water Company). Public acclaim for these accomplishments set the stage for a sympathetic response when he announced plans for a major new source of municipal water supply.

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Preface 1

Prologue: “A Misty Haze over Everything” 5

Chapter 1: Mulholland: A Man and an Aqueduct 9

Chapter 2: Th e Dam: Site Selection and Design 37

Chapter 3: Th e Dam: Construction, Operation, Failure 81

Chapter 4: Disaster Unleashed 129

Chapter 5: Civic Responsibility and Reparations 201

Chapter 6: Th e Politics of Safety: Inquest and Investigations 233

Chapter 7: Dam Building after the Flood 311

Chapter 8: Postscript: William Mulholland 323

Appendix A: How Fast Could the Reservoir Have Been Lowered? 337

Appendix B: Was Failure Inevitable? 341

Acknowledgments 345

About the Authors 346

Notes 347

Index 425

Preface 1

Prologue: “A Misty Haze over Everything” 5

Chapter 1: Mulholland: A Man and an Aqueduct 9

Chapter 2: Th e Dam: Site Selection and Design 37

Chapter 3: Th e Dam: Construction, Operation, Failure 81

Chapter 4: Disaster Unleashed 129

Chapter 5: Civic Responsibility and Reparations 201

Chapter 6: Th e Politics of Safety: Inquest and Investigations 233

Chapter 7: Dam Building after the Flood 311

Chapter 8: Postscript: William Mulholland 323

Appendix A: How Fast Could the Reservoir Have Been Lowered? 337

Appendix B: Was Failure Inevitable? 341

Acknowledgments 345

About the Authors 346

Notes 347

Index 425

Descriere

Heavy Ground explores the social, political, and technological history of the St. Francis Dam Disaster in California, the worst civil engineering disaster in twentieth-century American History. Approximately 400 people died in March 1928, when the concrete gravity dam built by Los Angeles engineer William Mulholland suddenly and tragically collapsed, releasing over 12 billion gallons of water into the Santa Clara River Valley.