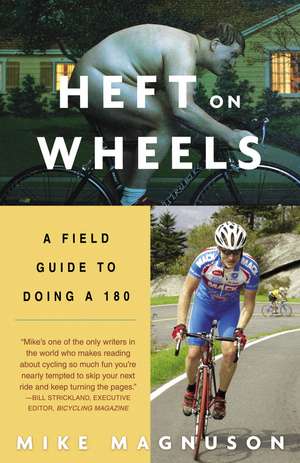

Heft on Wheels: A Field Guide to Doing a 180

Autor Mike Magnusonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2005

Not that long ago, Mike Magnuson was a self-described lummox with a bicycle. In the space of three months, he lost seventy-five pounds, quit smoking, stopped drinking, and morphed from the big guy at the back of the pack into a lean, mean cycling machine. Today, Mike is a 175-pound athlete competing in some of the most difficult one-day racing events in America. This irreverent and inspiring memoir charts every hilarious detail of his transformation, from the horrors of skin-tight XXL biking shorts to the miseries of nicotine withdrawal.

Heft on Wheels is an unforgettable book about getting from one place to another, in more ways than one.

Preț: 104.81 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.05€ • 20.94$ • 16.56£

20.05€ • 20.94$ • 16.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400052417

ISBN-10: 1400052416

Pagini: 252

Ilustrații: 20 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400052416

Pagini: 252

Ilustrații: 20 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Mike Magnuson teaches creative writing at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale and has written for Esquire, GQ, and Bicycling. He is the author of two novels and a memoir.

Extras

A truck will hit me.

I'm forty years old, the age of doom coming on and regret setting in, et cetera, but hey, I'm not caught up in all that. I'm happy. I'm not overweight anymore. I don't drink anymore or smoke anymore, and, imagine this, I'm not depressed anymore. I'm completely having a great time being healthier now than I've ever been and totally stronger, which is unbelievable sometimes to me. I mean, I expected, when I reached this age, that my athletic life's peak would occur on a Sunday afternoon in January, slamming pitchers of beer and eating peanuts and watching the NFL playoffs with my buddies at the sports bar, but I didn't go that way, I guess, or I didn't stay that way.

Instead, a couple of years ago, I spent twenty-five hundred bucks of my professor's salary on a race bicycle and started showing up three nights a week for a fast group road ride here in southern Illinois, at Carbondale Cycle, and three nights a week the group handed me my proverbial fat ass on a platter, which stood to reason. Back then, I smoked a pack a day and drank a case or two of beer a week and did shots of tequila or bourbon or kamikazes or you-name-it regularly at the bar with my graduate students. I weighed, suited up in a skintight XXL cycling jersey and shorts, 255 pounds. Five feet ten inches tall, 255 pounds. I shouldn't have shown up for group ride in that condition. I could have been hurt. Seriously. The group was just too much, too fast, flat-out beating the crap out of me every time. It's a miracle I didn't have a heart attack or a stroke or something trying to keep up.

I kept coming back for more, though, because I needed the crap beaten out of me. That's right. I needed atonement. I'm sure my associates at the bar in those days would agree. And, ah, how atonement comes with the group riding out of Carbondale on Dogwood Road into the mobile-home-littered hills and chip-and-seal roads of the Shawnee National Forest and hammering for forty-five miles, pounding over the hills, working inhumanely hard to spit each other off the back of the draftline and make each other suffer the way dropped cyclists have always suffered, like dogs. Man, back in my heavy days, I'd think if I could stay within sight of the group, even for short sections of the ride, I'd be scoring an extra-large moral and metaphorical victory. I win, I'd think, just because I'm participating. The big unhealthy man rides with the local fit fast road-bike group and gets dropped, the inspiring part being the odd truth: He doesn't get dropped as badly as you'd think he'd get dropped. Isn't it terrific the big guy can even stay close to those little bike racers?

But metaphor only goes so far in this world. Two hundred fifty-five fat drunken pounds: You ride road bikes with people who are a hundred times as fit and a hundred pounds lighter, they kick your ass. It's that simple.

Two years, twenty thousand miles of training and racing later, I weigh 173 pounds, and my lungs are as clear as my head is free of booze.

Speaking of metaphors, check out this one: If I used to go on group ride at Carbondale Cycle because I needed the crap beaten out of me, these days, I go on group ride because I possess the need and the ability to beat the crap out of others.

Let that be lesson number one.

So this Monday group ride in June, I'm the strongest rider. I'm not bragging or presenting myself as twice the man I really am. It's simply true. I'm the strongest. Another guy in town, my buddy Darren, we train together a lot and race for Team Mack Racing in the Masters 35-45 division and basically ride bikes way more than we should, he's much stronger than me and way more experienced and can and will obliterate me on the road whenever the situation warrants, like when I'm bragging about being the strongest rider on group ride, but shoot, he's not along for the festivities tonight. That means, and I vow to bear this responsibility with maturity and style, I'm the boss.

You can see me there, up front, in all my glory, setting the tempo and the vibe. I'm the guy in the Team Mack racing uniform--red, white, and pale blue--riding the battle-scarred Trek 5200 and wearing the loud red helmet and those stupid football-coach, sports-bar-goer glasses that I know look stupid but are important for me to wear, a small reminder of who I used to be before cycling. You will note, too, that I'm pulling our snaky dozen-rider group-ride phalanx at a comfortable, social, conversational pace, making sure we stay together and keep it mellow and have a positive experience in the early part of the ride, which isn't a corny thing to have, a positive experience.

I don't know why, incidentally, I used to think having a positive experience was somehow saccharine and wrong and inexcusable.

You know? Get over it. Be happy. Chat about this-and-that-type things, the awesome sunny weather, the big century ride coming up this weekend, the two-for-one sale on PowerBars at Kroger's. Have a few yuks. Let out a few not-very-serious groans. Cyclists are just so, so much happier than the drunks are at the bar. Cyclists are always saying awesome or exactly or that's cool or that's excellent, always praising each other's feats and encouraging each other to dig deep inside and find the thing that makes us work harder and care more and tune in to the frequency that makes us strong and happy and confident.

We ride east for the Carbondale town line on Dogwood Road, the roadside architecture beside which crumbles, along with the quality of the road surface, from new surgeon's homes to squalor and chickens scratching at the front-yard dirt. This is six in the evening, temperature in the high eighties, a golden slant-light behind us, not much traffic, once in a while a car up or a car back, no wind to speak of, couldn't be a better evening for cycling.

Out a ways, redbud trees and old scrub oaks, fallow fields, beat-up sheds and trailers and, near a long dirt driveway, a handpainted billboard warns of trouble afoot in our souls. The billboard depicts a sad-looking man reading a Bible with a skeleton figure leaning over his shoulder and making his life miserable; flames consume the background, but over the years the sun's faded them into cold white voids in the Old Testament distance. The scripture, from Ezekiel 18:31: "Why will ye die?"

Past the billboard, the road becomes a false flat rising over a series of badly filled potholes and, beyond that, around a rutted corner and down a steep S-curve descent at the bottom of which, what we've all been waiting for, the first sharp climb of the evening, the first attack of the night.

A cyclist at the rear yells Car Back, and the Car Back passes from one rider's voice to the next forward, all the way to the front, to me (ain't it cool it's me up front?), and I yell it, too, Car Back, to let everybody know I've heard the warning and will heed it. Our bikes make a whizzing noise, a popping noise over the chip-and-seal, tires over the loose pebbles, pebbles pinging the spokes, a loose shifter lever rattling here, a water bottle clattering its cage there, chains clicking through the gears' metal teeth, something low and terrified and heaving within cyclists' lungs. A car back.

It comes by, and cool, we're fine, the driver's one of us, a fellow cyclist, Christina, who just got done teaching a Spinning class at Great Shapes Fitness Center in Carbondale. She's heading home, a half-mile from here, at the end of a dirt road called Robin Lane. She's driving a huge 1991 Buick Roadmaster Estate Wagon with a Yakima roof rack on it, the biggest model Yakima makes, big enough to hold nine bikes, rods extending a full foot beyond the roof on each side. Christina, she totally understands how to pass a group of cyclists; she gives us space. She slows appropriately and swings wide around us, and we're all waving and like hey, Christina. After she's around us and disappearing into the S-curve ahead, we're like she's great. She's a really strong rider. She's so awesome.

Everybody's positive. It's so cool we're this way.

We've got a car back again and voices passing Car Back forward, and a Dodge pickup goes by, faster than Christina, wilder, closer to us, but then again, the road's narrowing and getting potholed and nasty with more pebbles and rising dust. A vehicle moving at any speed, under these conditions, could appear to be moving faster than it's actually moving, what with the high-pitched waterfall noise the bikes make in the gravel and the closeness of the trees, but it's okay, the truck's gone around the corner and down the S-turn ahead of the group and way out of sight.

The road seems clear to me, so all right already, I'll throw down the first attack and make it an emphatic one to boot. I get low in the handlebar drops now and slingshot through the corner and yell clear and lift out of the saddle and run on the pedals to the crest of the rise, piece of cake to put out this effort, hardly elevates my heart rate to do it. Right here, right now, I'm so aware and so grateful that my life has transformed into this magnificent thing I can do, feels like I'm flying on the road, as if I'll reach the top of the hill and keep rising, like E.T. past the open guts of the moon, twenty miles an hour at the top, accelerating over the blind crest and leaning forward on the bike to dive hard into the descent, passing through twenty-five miles per hour now.

A Dodge Dakota, green in the evening sun, fifty yards ahead of me, pulled to the left shoulder, wrong side of the road, driver's-side door next to a row of mailboxes--looks like the guy in the truck's checking his mail and his brakelights go off and he pulls forward and I just keep on pedaling and positioning myself to swing in behind him and draft up the next rise, keep the speed up over twenty-five easy, get a head start on spanking everybody over the next mile toward Spillway Road.

He's Robert, construction worker, home from framing in a set of master-bedroom doorways at a new half-million-dollar home at the Shawnee Hills Golf Community. He's thirty-three, a guy who's been, as he'll probably tell you, up and down the block a few times. He doesn't have any mail worth paying attention to, a couple of coupon circulars, nothing, no reason to turn right off Dogwood onto Robin Lane and go inside his house and set the mail on the kitchen table to let his old lady Cindy know he's been there, he's come home and proved he at least cares before cruising over to his friend Tom's trailer and hanging out till ten, but what the hell, he'll drive down to the house first, see if everything's okay. He pops the truck in reverse then forward and Ys into me, I'm like whoa and he's gonna hit me and thwack into his front fender and over the hood and spiraling through the air twenty-five feet, around and around and end over end like a skater doing a double axel with a three-quarter twist toward oblivion. The bike separates from my feet and soars due east down Dogwood, and I fly the direction my life's about to go for a while: south and into the ditch.

I land headfirst. I'll remember that forever: smashing headfirst into the roadside gravel, then the follow-through momentum into my shoulder, then flipping over onto my back, and okay, okay: I'm sitting upright in the weeds, elbows propped comfortably on my inner thighs, hands clasped together as if in prayer, as if God has lifted me off my bike and the obsessive life I've been living on the road and slammed me into the ground, upright, where I'll be in proper position to reflect.

God says, "Feel like praying now?"

I say, "As a matter of fact--"

My left leg is trashed. I know this because I can't seem to move it much or I don't think I should just yet. A lump's already rising in the shin's middle, and blood's emerging from an array of gashes on my inner leg at the knee. A dozen or so tiny grass flies have already settled in on the blood, they pop up off it and sink back in, and I can hear riders unclicking from their pedals around me, the sound of bicycle cleats walking on the road. I can see the truck, the guy in it, bearded guy with a flannel shirt and a feed cap and a ponytail, staring blankly forward into the gravel of Robin Lane.

From the Hardcover edition.

I'm forty years old, the age of doom coming on and regret setting in, et cetera, but hey, I'm not caught up in all that. I'm happy. I'm not overweight anymore. I don't drink anymore or smoke anymore, and, imagine this, I'm not depressed anymore. I'm completely having a great time being healthier now than I've ever been and totally stronger, which is unbelievable sometimes to me. I mean, I expected, when I reached this age, that my athletic life's peak would occur on a Sunday afternoon in January, slamming pitchers of beer and eating peanuts and watching the NFL playoffs with my buddies at the sports bar, but I didn't go that way, I guess, or I didn't stay that way.

Instead, a couple of years ago, I spent twenty-five hundred bucks of my professor's salary on a race bicycle and started showing up three nights a week for a fast group road ride here in southern Illinois, at Carbondale Cycle, and three nights a week the group handed me my proverbial fat ass on a platter, which stood to reason. Back then, I smoked a pack a day and drank a case or two of beer a week and did shots of tequila or bourbon or kamikazes or you-name-it regularly at the bar with my graduate students. I weighed, suited up in a skintight XXL cycling jersey and shorts, 255 pounds. Five feet ten inches tall, 255 pounds. I shouldn't have shown up for group ride in that condition. I could have been hurt. Seriously. The group was just too much, too fast, flat-out beating the crap out of me every time. It's a miracle I didn't have a heart attack or a stroke or something trying to keep up.

I kept coming back for more, though, because I needed the crap beaten out of me. That's right. I needed atonement. I'm sure my associates at the bar in those days would agree. And, ah, how atonement comes with the group riding out of Carbondale on Dogwood Road into the mobile-home-littered hills and chip-and-seal roads of the Shawnee National Forest and hammering for forty-five miles, pounding over the hills, working inhumanely hard to spit each other off the back of the draftline and make each other suffer the way dropped cyclists have always suffered, like dogs. Man, back in my heavy days, I'd think if I could stay within sight of the group, even for short sections of the ride, I'd be scoring an extra-large moral and metaphorical victory. I win, I'd think, just because I'm participating. The big unhealthy man rides with the local fit fast road-bike group and gets dropped, the inspiring part being the odd truth: He doesn't get dropped as badly as you'd think he'd get dropped. Isn't it terrific the big guy can even stay close to those little bike racers?

But metaphor only goes so far in this world. Two hundred fifty-five fat drunken pounds: You ride road bikes with people who are a hundred times as fit and a hundred pounds lighter, they kick your ass. It's that simple.

Two years, twenty thousand miles of training and racing later, I weigh 173 pounds, and my lungs are as clear as my head is free of booze.

Speaking of metaphors, check out this one: If I used to go on group ride at Carbondale Cycle because I needed the crap beaten out of me, these days, I go on group ride because I possess the need and the ability to beat the crap out of others.

Let that be lesson number one.

So this Monday group ride in June, I'm the strongest rider. I'm not bragging or presenting myself as twice the man I really am. It's simply true. I'm the strongest. Another guy in town, my buddy Darren, we train together a lot and race for Team Mack Racing in the Masters 35-45 division and basically ride bikes way more than we should, he's much stronger than me and way more experienced and can and will obliterate me on the road whenever the situation warrants, like when I'm bragging about being the strongest rider on group ride, but shoot, he's not along for the festivities tonight. That means, and I vow to bear this responsibility with maturity and style, I'm the boss.

You can see me there, up front, in all my glory, setting the tempo and the vibe. I'm the guy in the Team Mack racing uniform--red, white, and pale blue--riding the battle-scarred Trek 5200 and wearing the loud red helmet and those stupid football-coach, sports-bar-goer glasses that I know look stupid but are important for me to wear, a small reminder of who I used to be before cycling. You will note, too, that I'm pulling our snaky dozen-rider group-ride phalanx at a comfortable, social, conversational pace, making sure we stay together and keep it mellow and have a positive experience in the early part of the ride, which isn't a corny thing to have, a positive experience.

I don't know why, incidentally, I used to think having a positive experience was somehow saccharine and wrong and inexcusable.

You know? Get over it. Be happy. Chat about this-and-that-type things, the awesome sunny weather, the big century ride coming up this weekend, the two-for-one sale on PowerBars at Kroger's. Have a few yuks. Let out a few not-very-serious groans. Cyclists are just so, so much happier than the drunks are at the bar. Cyclists are always saying awesome or exactly or that's cool or that's excellent, always praising each other's feats and encouraging each other to dig deep inside and find the thing that makes us work harder and care more and tune in to the frequency that makes us strong and happy and confident.

We ride east for the Carbondale town line on Dogwood Road, the roadside architecture beside which crumbles, along with the quality of the road surface, from new surgeon's homes to squalor and chickens scratching at the front-yard dirt. This is six in the evening, temperature in the high eighties, a golden slant-light behind us, not much traffic, once in a while a car up or a car back, no wind to speak of, couldn't be a better evening for cycling.

Out a ways, redbud trees and old scrub oaks, fallow fields, beat-up sheds and trailers and, near a long dirt driveway, a handpainted billboard warns of trouble afoot in our souls. The billboard depicts a sad-looking man reading a Bible with a skeleton figure leaning over his shoulder and making his life miserable; flames consume the background, but over the years the sun's faded them into cold white voids in the Old Testament distance. The scripture, from Ezekiel 18:31: "Why will ye die?"

Past the billboard, the road becomes a false flat rising over a series of badly filled potholes and, beyond that, around a rutted corner and down a steep S-curve descent at the bottom of which, what we've all been waiting for, the first sharp climb of the evening, the first attack of the night.

A cyclist at the rear yells Car Back, and the Car Back passes from one rider's voice to the next forward, all the way to the front, to me (ain't it cool it's me up front?), and I yell it, too, Car Back, to let everybody know I've heard the warning and will heed it. Our bikes make a whizzing noise, a popping noise over the chip-and-seal, tires over the loose pebbles, pebbles pinging the spokes, a loose shifter lever rattling here, a water bottle clattering its cage there, chains clicking through the gears' metal teeth, something low and terrified and heaving within cyclists' lungs. A car back.

It comes by, and cool, we're fine, the driver's one of us, a fellow cyclist, Christina, who just got done teaching a Spinning class at Great Shapes Fitness Center in Carbondale. She's heading home, a half-mile from here, at the end of a dirt road called Robin Lane. She's driving a huge 1991 Buick Roadmaster Estate Wagon with a Yakima roof rack on it, the biggest model Yakima makes, big enough to hold nine bikes, rods extending a full foot beyond the roof on each side. Christina, she totally understands how to pass a group of cyclists; she gives us space. She slows appropriately and swings wide around us, and we're all waving and like hey, Christina. After she's around us and disappearing into the S-curve ahead, we're like she's great. She's a really strong rider. She's so awesome.

Everybody's positive. It's so cool we're this way.

We've got a car back again and voices passing Car Back forward, and a Dodge pickup goes by, faster than Christina, wilder, closer to us, but then again, the road's narrowing and getting potholed and nasty with more pebbles and rising dust. A vehicle moving at any speed, under these conditions, could appear to be moving faster than it's actually moving, what with the high-pitched waterfall noise the bikes make in the gravel and the closeness of the trees, but it's okay, the truck's gone around the corner and down the S-turn ahead of the group and way out of sight.

The road seems clear to me, so all right already, I'll throw down the first attack and make it an emphatic one to boot. I get low in the handlebar drops now and slingshot through the corner and yell clear and lift out of the saddle and run on the pedals to the crest of the rise, piece of cake to put out this effort, hardly elevates my heart rate to do it. Right here, right now, I'm so aware and so grateful that my life has transformed into this magnificent thing I can do, feels like I'm flying on the road, as if I'll reach the top of the hill and keep rising, like E.T. past the open guts of the moon, twenty miles an hour at the top, accelerating over the blind crest and leaning forward on the bike to dive hard into the descent, passing through twenty-five miles per hour now.

A Dodge Dakota, green in the evening sun, fifty yards ahead of me, pulled to the left shoulder, wrong side of the road, driver's-side door next to a row of mailboxes--looks like the guy in the truck's checking his mail and his brakelights go off and he pulls forward and I just keep on pedaling and positioning myself to swing in behind him and draft up the next rise, keep the speed up over twenty-five easy, get a head start on spanking everybody over the next mile toward Spillway Road.

He's Robert, construction worker, home from framing in a set of master-bedroom doorways at a new half-million-dollar home at the Shawnee Hills Golf Community. He's thirty-three, a guy who's been, as he'll probably tell you, up and down the block a few times. He doesn't have any mail worth paying attention to, a couple of coupon circulars, nothing, no reason to turn right off Dogwood onto Robin Lane and go inside his house and set the mail on the kitchen table to let his old lady Cindy know he's been there, he's come home and proved he at least cares before cruising over to his friend Tom's trailer and hanging out till ten, but what the hell, he'll drive down to the house first, see if everything's okay. He pops the truck in reverse then forward and Ys into me, I'm like whoa and he's gonna hit me and thwack into his front fender and over the hood and spiraling through the air twenty-five feet, around and around and end over end like a skater doing a double axel with a three-quarter twist toward oblivion. The bike separates from my feet and soars due east down Dogwood, and I fly the direction my life's about to go for a while: south and into the ditch.

I land headfirst. I'll remember that forever: smashing headfirst into the roadside gravel, then the follow-through momentum into my shoulder, then flipping over onto my back, and okay, okay: I'm sitting upright in the weeds, elbows propped comfortably on my inner thighs, hands clasped together as if in prayer, as if God has lifted me off my bike and the obsessive life I've been living on the road and slammed me into the ground, upright, where I'll be in proper position to reflect.

God says, "Feel like praying now?"

I say, "As a matter of fact--"

My left leg is trashed. I know this because I can't seem to move it much or I don't think I should just yet. A lump's already rising in the shin's middle, and blood's emerging from an array of gashes on my inner leg at the knee. A dozen or so tiny grass flies have already settled in on the blood, they pop up off it and sink back in, and I can hear riders unclicking from their pedals around me, the sound of bicycle cleats walking on the road. I can see the truck, the guy in it, bearded guy with a flannel shirt and a feed cap and a ponytail, staring blankly forward into the gravel of Robin Lane.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Mike's one of the only writers in the world who makes reading about cycling so much fun you're nearly tempted to skip your next ride and keep turning the pages.” —Bill Strickland, executive editor, Bicycling magazine

“Forget Dr. Phil and the South Beach Diet. Forget Atkins and scary pills. Mike Magnuson found another, much more enjoyable way to shed pounds and get healthy: cycling.” —Chicago Sun-Times

“Forget Dr. Phil and the South Beach Diet. Forget Atkins and scary pills. Mike Magnuson found another, much more enjoyable way to shed pounds and get healthy: cycling.” —Chicago Sun-Times