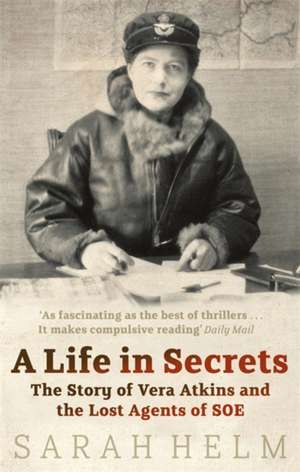

Helm, S: Life In Secrets

en Limba Engleză Paperback – iun 2006

During World War Two the Special Operation Executive's French Section sent more than 400 agents into Occupied France -- at least 100 never returned and were reported 'Missing Believed Dead' after the war. Twelve of these were women who died in German concentration camps -- some were tortured, some were shot, and some died in the gas chambers. Vera Atkins had helped prepare these women for their missions, and when the war was over she went out to Germany to find out what happened to them and the other agents lost behind enemy lines.

But while the woman who carried out this extraordinary mission appeared quintessentially English, she was nothing of the sort. Vera Atkins, who never married, covered her life in mystery so that even her closest family knew almost nothing of her past. In A LIFE IN SECRETS Sarah Helm has stripped away Vera's many veils and -- with unprecedented access to official and private papers, and the cooperation of Vera's relatives -- vividly reconstructed an extraordinary life.

Preț: 64.58 lei

Preț vechi: 83.53 lei

-23% Nou

12.36€ • 12.97$ • 10.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 martie-03 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0349119368

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: Section: 16, b/w

Dimensiuni: 130 x 197 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Locul publicării:United Kingdom