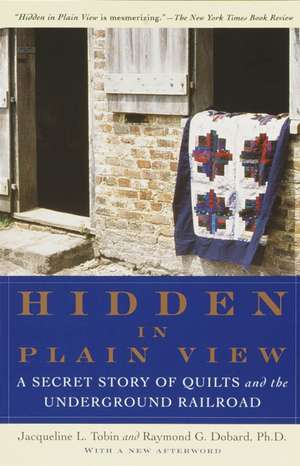

Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad

Autor Jacqueline L. Tobin, Raymond G. Dobard Cuesta Benberryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 1999

"A groundbreaking work."--Emerge

In Hidden in Plain View, historian Jacqueline Tobin and scholar Raymond Dobard offer the first proof that certain quilt patterns, including a prominent one called the Charleston Code, were, in fact, essential tools for escape along the Underground Railroad. In 1993, historian Jacqueline Tobin met African American quilter Ozella Williams amid piles of beautiful handmade quilts in the Old Market Building of Charleston, South Carolina. With the admonition to "write this down," Williams began to describe how slaves made coded quilts and used them to navigate their escape on the Underground Railroad. But just as quickly as she started, Williams stopped, informing Tobin that she would learn the rest when she was "ready." During the three years it took for Williams's narrative to unfold--and as the friendship and trust between the two women grew--Tobin enlisted Raymond Dobard, Ph.D., an art history professor and well-known African American quilter, to help unravel the mystery.

Part adventure and part history, Hidden in Plain View traces the origin of the Charleston Code from Africa to the Carolinas, from the low-country island Gullah peoples to free blacks living in the cities of the North, and shows how three people from completely different backgrounds pieced together one amazing American story.

Preț: 78.81 lei

Preț vechi: 100.73 lei

-22% Nou

Puncte Express: 118

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.09€ • 16.39$ • 12.68£

15.09€ • 16.39$ • 12.68£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385497671

ISBN-10: 0385497679

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 2-8 PG COL INS, LINE DR THRGHT

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385497679

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 2-8 PG COL INS, LINE DR THRGHT

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

JACQUELINE TOBIN is a teacher, collector, and writer of women's stories. She lives in Colorado. RAYMOND DOBARD, Ph.D., is an art history professor at Howard University and a nationally known African-American quilter. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Extras

"Write This Down"

In 1994 I traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, to learn more about the sweet-grass baskets unique to this area and to hear the stories of the African American craftswomen who make them. Charleston is rich in history. A port city, where the Ashley River meets the Cooper to form (as locals like to say) the beginnings of the Atlantic Ocean, Charleston today is a place whose buildings and culture reflect the combined and separate histories of American and African American peoples. It is unique as the location where black slaves first set foot on American soil and once outnumbered the white population four to one.

A walk through the historic district of Charleston is like a walk through the corridors of American Southern history. Here, one is confronted by all the hustle and bustle of the retentions and re-creations of a bygone era. At the heart of historic Charleston is an imposing brick enclosure with open sides, known as The Old Marketplace. It looks very much as it did over one hundred years ago, as it still defines the length of the district. As it was in years gone by, the Marketplace is still the center of commerce for the area. Under the roof of the structure, long wooden cables, laid end-to-end, go on for blocks to create two narrow avenues for selling wares. As early as 1841 it was a marketplace for fresh vegetables, fish, meats, and ocher goods brought to Charleston from the surrounding farms and plantations and other coastal ports and faraway lands; it is still a vendor's market, but with stark contrasts between the old and the new. African American women sit by pails of sweet grass and weave baskets much as their African ancestors did over a hundred years ago. But these craftswomen, many of them descendants of slaves, are now surrounded by merchants of flea market trinkets, Southern memorabilia, and newer, cheaper baskets from China and Thailand.

The smell of the daily ocean catch or freshly slaughtered meats is no longer the predominant early morning smell of the Marketplace. Today the aroma of freshly baked cookies and newly ground coffee beans from the gourmet shops surrounding the area compete for attention. Certain sounds can still be heard; the din of tourists and locals alike crowding the streets and trying to avoid the horses, their hooves providing the percussive rhythm for this city as they clop loudly over original cobblestone streets. Carriages are drawn around the district, past the Custom House and on toward the Battery, where decorative wrought-iron fences accentuate the largess of old historic homes. Taverns and brothels have given way to fern bars and upscale hotels touting Southern hospitality and cuisine. Newly restored, on a lesser traveled street, is the original slave mart, now a historical museum, whose presence jars us into remembering a less civil piece of the history of this Southern port city.

As I walked the aisles of the Marketplace, I found myself standing in front of a stall lined with quilts of all sizes, colors, and patterns. I was drawn in by these piles of quilts, as long-forgotten memories of my grandmother's quilt box, filled with her handmade quilts, were brought to mind. Before I could do much looking or reminiscing, an elderly African American woman, dressed in brightly colored, geometrically patterned African garb, slowly walked up to me from the back of the stall. She motioned me to follow her to the back, where an old metal folding chair sat surrounded by more quilts. "Look," she said. She chose one of the quilts from the pile, unrolled it, and while pointing to it said, "Did you know these quilts were used by slaves to communicate on the Underground Railroad?" The old quilter continued to speak but I could not hear her clearly in the midst of the noise of the Marketplace around us. I wasn't sure why she was telling me, a complete stranger, this unusual story. I listened politely for a short while. When I didn't ask any questions, she stopped talking. I purchased a beautiful, hand-tied quilt and left with her flyer advertising "historic Charleston Marketplace" quilts.

I returned home with my quilt and memories of Charleston. I hung my quilt and laid my memories aside. I didn't think too much about my conversation with this quilter until several months later when I came across her flyer again. I remembered the story she had started to tell me and I wondered about it. I had never heard such a story or read about it in any books. Was there more to the story? The flyer listed the quilter's name and phone number. I decided to call Mrs. Ozella McDaniel Williams and see if she would be willing to tell me more. When she answered the phone, I reminded her of who I was and asked if I might hear more about how quilts were used on the Underground Railroad. She told me curtly to call back the next evening, which I did. At that time she said, "I can't speak to you about this right now." When I tried pressing her, she laughed quietly and whispered into the phone, "Don't worry, you'll get the story when you are ready." And then she hung up.

Ozella had now added an element of intrigue to the already fascinating story. I was hooked. What did she mean by "you'll get the story when you're ready"? I felt I had to explore the story further. If she wouldn't talk, perhaps others would. I began to contact every African American quilter and quilt scholar I could find. I traveled down the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans, stopping to visit quilters and scholars. I toured plantations and slave quarters, looking for clues. Before long, I was speaking to a fairly close-knit circle of people that included art historians, African American quilters, African textile experts, and folklorists. Most of them had heard that quilts had been used as a means of secret communication on the Underground Railroad, but none were exactly sure how. Some referenced particular quilt patterns, some mentioned the stitching, and others cited specific colors. I was not able to find any slave quilts that could verify these stories. Most quilt scholars agreed that few slave quilts had survived the constant strain of excessive use, the poor quality of fabric they had probably been sewn from, and the continual washing in harsh lye soap that would eventually cause them to disintegrate.

As a white person conducting research into African American scholarship, I was hesitant at times to continue. Some people were reluctant to share family stories with me. At one point I suggested that Dr. Raymond Dobard, one of the scholars I was conversing with, continue my research by contacting Ozella himself. I was hoping that she would speak more freely to another African American. Raymond, an art history professor at Howard University, a renowned quilter, and a known expert on African American quilts as they relate to the Underground Railroad, seemed to me to be the perfect person to pursue this research with Ozella. However, when I made my suggestion, Raymond insisted that I was the one with whom Ozella felt comfortable telling the story initially and thus should be the one to pursue it. He told me to be patient and that I would indeed get the story when I was ready. With his encouragement I continued my research.

Three years after first hearing the story, I had come full circle with my research, but there were still missing pieces. I could add nothing new to the information that was already out there. Still lacking was an elaboration of the story connecting quilts and the Underground Railroad. I was hoping for a final link connecting all the quilt stories with details. My intuition told me that Ozella knew more than what she'd already told me. The only way to find out would be to return to Charleston and see if she would speak to me again.

Without contacting her first, I arranged a return visit to Charleston. If Ozella was reluctant to speak, I didn't wane to give her any time to think about it and turn me down without my ability to plead my case in person. Besides, I had done my homework, and maybe, I thought, I was now "ready" to receive the story in full. Armed with information and questions, I felt the time was right.

Upon my arrival, I took a carriage tour around the historic Charleston district. I wanted to immerse myself once again in the flavor of the Old South before attempting to talk with Ozella. As the carriage passed the Marketplace, I turned to look, my eyes straining to recognize my quilter friend's face. I recognized her immediately, sitting in the same location, amidst her cables of quilts, just as I had seen her three years prior. Today she was dressed all in white. She had on white slacks and a white blouse decorated with a huge lavender flower hand-painted on the front. She wore a large straw hat with a white band that had the same lavender flower painted on it as well.

I completed my carriage ride and walked slowly down the aisles of the Marketplace. I was nervous about meeting her again. Would she remember me? I wondered. What if I had come this far and she still wouldn't speak to me? Or, worse yet, what if she really didn't know anything more than she had already told me? With notebook in hand I took a deep breath and hesitantly approached her. Her back was turned to me as she stood quietly arranging her quilts. I cleared my throat to get her attention. When she turned, I tried to hand her my business card and started to explain who I was and why I was there. With a wave of her hand, brushing my card away, she interrupted me and said, "I don't care who you is. You is people and that is all that matters. Bring over some of those quilts and make a seat for yourself beside me. Get yourself comfortable. "

I hesitated, but only briefly. If she was ready to talk, I was ready to listen. I was concerned about sitting on her handmade works of art, but she didn't seem to care. She positioned herself on the metal folding chair, moving quilts to either side of her and around her. I chose several rolled quilts and brought them over in front of her. After placing them on the ground, I sat down in from of her. From this position I was looking directly up into Ozella's face. She pulled her folding chair even closer to me. I became aware that she was now physically creating a space around us, obviously meant only for her and me. After seating herself on the folding chair she leaned down coward me, one hand resting on her knee, her index finger pointing to my notepad. She pushed her straw hat farther back on her head and with her other hand she directed me, "Write this down."

In 1994 I traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, to learn more about the sweet-grass baskets unique to this area and to hear the stories of the African American craftswomen who make them. Charleston is rich in history. A port city, where the Ashley River meets the Cooper to form (as locals like to say) the beginnings of the Atlantic Ocean, Charleston today is a place whose buildings and culture reflect the combined and separate histories of American and African American peoples. It is unique as the location where black slaves first set foot on American soil and once outnumbered the white population four to one.

A walk through the historic district of Charleston is like a walk through the corridors of American Southern history. Here, one is confronted by all the hustle and bustle of the retentions and re-creations of a bygone era. At the heart of historic Charleston is an imposing brick enclosure with open sides, known as The Old Marketplace. It looks very much as it did over one hundred years ago, as it still defines the length of the district. As it was in years gone by, the Marketplace is still the center of commerce for the area. Under the roof of the structure, long wooden cables, laid end-to-end, go on for blocks to create two narrow avenues for selling wares. As early as 1841 it was a marketplace for fresh vegetables, fish, meats, and ocher goods brought to Charleston from the surrounding farms and plantations and other coastal ports and faraway lands; it is still a vendor's market, but with stark contrasts between the old and the new. African American women sit by pails of sweet grass and weave baskets much as their African ancestors did over a hundred years ago. But these craftswomen, many of them descendants of slaves, are now surrounded by merchants of flea market trinkets, Southern memorabilia, and newer, cheaper baskets from China and Thailand.

The smell of the daily ocean catch or freshly slaughtered meats is no longer the predominant early morning smell of the Marketplace. Today the aroma of freshly baked cookies and newly ground coffee beans from the gourmet shops surrounding the area compete for attention. Certain sounds can still be heard; the din of tourists and locals alike crowding the streets and trying to avoid the horses, their hooves providing the percussive rhythm for this city as they clop loudly over original cobblestone streets. Carriages are drawn around the district, past the Custom House and on toward the Battery, where decorative wrought-iron fences accentuate the largess of old historic homes. Taverns and brothels have given way to fern bars and upscale hotels touting Southern hospitality and cuisine. Newly restored, on a lesser traveled street, is the original slave mart, now a historical museum, whose presence jars us into remembering a less civil piece of the history of this Southern port city.

As I walked the aisles of the Marketplace, I found myself standing in front of a stall lined with quilts of all sizes, colors, and patterns. I was drawn in by these piles of quilts, as long-forgotten memories of my grandmother's quilt box, filled with her handmade quilts, were brought to mind. Before I could do much looking or reminiscing, an elderly African American woman, dressed in brightly colored, geometrically patterned African garb, slowly walked up to me from the back of the stall. She motioned me to follow her to the back, where an old metal folding chair sat surrounded by more quilts. "Look," she said. She chose one of the quilts from the pile, unrolled it, and while pointing to it said, "Did you know these quilts were used by slaves to communicate on the Underground Railroad?" The old quilter continued to speak but I could not hear her clearly in the midst of the noise of the Marketplace around us. I wasn't sure why she was telling me, a complete stranger, this unusual story. I listened politely for a short while. When I didn't ask any questions, she stopped talking. I purchased a beautiful, hand-tied quilt and left with her flyer advertising "historic Charleston Marketplace" quilts.

I returned home with my quilt and memories of Charleston. I hung my quilt and laid my memories aside. I didn't think too much about my conversation with this quilter until several months later when I came across her flyer again. I remembered the story she had started to tell me and I wondered about it. I had never heard such a story or read about it in any books. Was there more to the story? The flyer listed the quilter's name and phone number. I decided to call Mrs. Ozella McDaniel Williams and see if she would be willing to tell me more. When she answered the phone, I reminded her of who I was and asked if I might hear more about how quilts were used on the Underground Railroad. She told me curtly to call back the next evening, which I did. At that time she said, "I can't speak to you about this right now." When I tried pressing her, she laughed quietly and whispered into the phone, "Don't worry, you'll get the story when you are ready." And then she hung up.

Ozella had now added an element of intrigue to the already fascinating story. I was hooked. What did she mean by "you'll get the story when you're ready"? I felt I had to explore the story further. If she wouldn't talk, perhaps others would. I began to contact every African American quilter and quilt scholar I could find. I traveled down the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans, stopping to visit quilters and scholars. I toured plantations and slave quarters, looking for clues. Before long, I was speaking to a fairly close-knit circle of people that included art historians, African American quilters, African textile experts, and folklorists. Most of them had heard that quilts had been used as a means of secret communication on the Underground Railroad, but none were exactly sure how. Some referenced particular quilt patterns, some mentioned the stitching, and others cited specific colors. I was not able to find any slave quilts that could verify these stories. Most quilt scholars agreed that few slave quilts had survived the constant strain of excessive use, the poor quality of fabric they had probably been sewn from, and the continual washing in harsh lye soap that would eventually cause them to disintegrate.

As a white person conducting research into African American scholarship, I was hesitant at times to continue. Some people were reluctant to share family stories with me. At one point I suggested that Dr. Raymond Dobard, one of the scholars I was conversing with, continue my research by contacting Ozella himself. I was hoping that she would speak more freely to another African American. Raymond, an art history professor at Howard University, a renowned quilter, and a known expert on African American quilts as they relate to the Underground Railroad, seemed to me to be the perfect person to pursue this research with Ozella. However, when I made my suggestion, Raymond insisted that I was the one with whom Ozella felt comfortable telling the story initially and thus should be the one to pursue it. He told me to be patient and that I would indeed get the story when I was ready. With his encouragement I continued my research.

Three years after first hearing the story, I had come full circle with my research, but there were still missing pieces. I could add nothing new to the information that was already out there. Still lacking was an elaboration of the story connecting quilts and the Underground Railroad. I was hoping for a final link connecting all the quilt stories with details. My intuition told me that Ozella knew more than what she'd already told me. The only way to find out would be to return to Charleston and see if she would speak to me again.

Without contacting her first, I arranged a return visit to Charleston. If Ozella was reluctant to speak, I didn't wane to give her any time to think about it and turn me down without my ability to plead my case in person. Besides, I had done my homework, and maybe, I thought, I was now "ready" to receive the story in full. Armed with information and questions, I felt the time was right.

Upon my arrival, I took a carriage tour around the historic Charleston district. I wanted to immerse myself once again in the flavor of the Old South before attempting to talk with Ozella. As the carriage passed the Marketplace, I turned to look, my eyes straining to recognize my quilter friend's face. I recognized her immediately, sitting in the same location, amidst her cables of quilts, just as I had seen her three years prior. Today she was dressed all in white. She had on white slacks and a white blouse decorated with a huge lavender flower hand-painted on the front. She wore a large straw hat with a white band that had the same lavender flower painted on it as well.

I completed my carriage ride and walked slowly down the aisles of the Marketplace. I was nervous about meeting her again. Would she remember me? I wondered. What if I had come this far and she still wouldn't speak to me? Or, worse yet, what if she really didn't know anything more than she had already told me? With notebook in hand I took a deep breath and hesitantly approached her. Her back was turned to me as she stood quietly arranging her quilts. I cleared my throat to get her attention. When she turned, I tried to hand her my business card and started to explain who I was and why I was there. With a wave of her hand, brushing my card away, she interrupted me and said, "I don't care who you is. You is people and that is all that matters. Bring over some of those quilts and make a seat for yourself beside me. Get yourself comfortable. "

I hesitated, but only briefly. If she was ready to talk, I was ready to listen. I was concerned about sitting on her handmade works of art, but she didn't seem to care. She positioned herself on the metal folding chair, moving quilts to either side of her and around her. I chose several rolled quilts and brought them over in front of her. After placing them on the ground, I sat down in from of her. From this position I was looking directly up into Ozella's face. She pulled her folding chair even closer to me. I became aware that she was now physically creating a space around us, obviously meant only for her and me. After seating herself on the folding chair she leaned down coward me, one hand resting on her knee, her index finger pointing to my notepad. She pushed her straw hat farther back on her head and with her other hand she directed me, "Write this down."

Recenzii

"Startling--intriguing."--The New York Times

Descriere

For the first time, the secret codes used in slave quilt patterns that served as maps to escape on the Underground Railroad are revealed--suggesting that there was an organized African-American resistance movement that predated the Abolitionist crusade. Two 8-page color photos inserts. Line drawings.