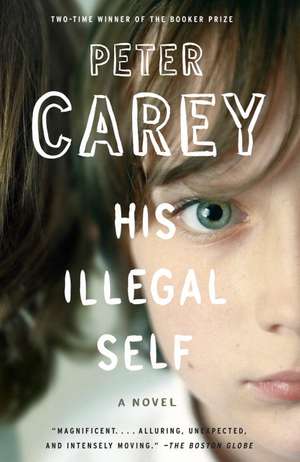

His Illegal Self: A Love Story

Autor Peter Stafford Careyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2009

Preț: 80.41 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 121

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.39€ • 16.02$ • 13.01£

15.39€ • 16.02$ • 13.01£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307276490

ISBN-10: 030727649X

Pagini: 271

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 030727649X

Pagini: 271

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Peter Carey is the author of ten novels, and has twice received the Booker Prize. His other honors include the Commonwealth Writer's Prize and the

Miles Franklin Literary Award. Born in Australia, he now lives in New York City.

Miles Franklin Literary Award. Born in Australia, he now lives in New York City.

Extras

Chapter 1

There were no photographs of the boy's father in the house upstate. He had been persona non grata since Christmas 1964, six months before the boy was born. There were plenty of pictures of his mom. There she was with short blond hair, her eyes so white against her tan. And that was her also, with black hair, not even a sister to the blonde girl, although maybe they shared a kind of bright attention.

She was an actress like her grandma, it was said. She could change herself into anyone. The boy had no reason to disbelieve this, not having seen his mother since the age of two. She was the prodigal daughter, the damaged saint, like the icon that Grandpa once brought back from Athens—shining silver, musky incense—although no one had ever told the boy how his mother smelled.

Then, when the boy was almost eight, a woman stepped out of the elevator into the apartment on East Sixty-second Street and he recognized her straightaway. No one had told him to expect it.

That was pretty typical of growing up with Grandma Selkirk. You were some kind of lovely insect, expected to know things through your feelers, by the kaleidoscope patterns in the others' eyes. No one would dream of saying, Here is your mother returned to you. Instead his grandma told him to put on his sweater. She collected her purse, found her keys and then all three of them walked down to Bloomingdale's as if it were a deli. This was normal life. Across Park, down Lex. The boy stood close beside the splendid stranger with the lumpy khaki pack strapped onto her back. That was her blood, he could hear it now, pounding in his ears. He had imagined her a wound-up spring, light, bright, blonde, like Grandma in full whir. She was completely different; she was just the same. By the time they were in Bloomingdale's she was arguing about his name.

What did you just call Che? she asked the grandma.

His name, replied Grandma Selkirk, ruffling the boy's darkening summer hair. That's what I called him. She gave the mother a bright white smile. The boy thought, Oh, oh!

It sounded like Jay, the mother said.

The grandma turned sharply to the shopgirl who was busy staring at the hippie mother.

Let me try the Artemis.

Grandma Selkirk was what they call an Upper East Side woman—cheekbones, tailored gray hair—but that was not what she called herself. I am the last bohemian, she liked to say, to the boy, particularly, meaning that no one told her what to do, at least not since Pa Selkirk had thrown the Buddha out the window and gone to live with the Poison Dwarf.

Grandpa had done a whole heap of other things besides, like giving up his board seat, like going spiritual. When Grandpa moved out, Grandma moved out too. The Park Avenue apartment was hers, always had been, but now they used it maybe once a month. Instead they spent their time on Kenoza Lake near Jeffersonville, New York, a town of 400 where "no one" lived. Grandma made raku pots and rowed a heavy clinker boat. The boy hardly saw his grandpa after that, except sometimes there were postcards with very small handwriting. Buster Selkirk could fit a whole ball game on a single card.

For these last five years it had been just Grandma and the boy together and she threaded the squirming live bait to hook the largemouth bass and, also, called him Jay instead of Che. There were no kids to play with. There were no pets because Grandma was allergic. But in fall there were Cox's pippins, wild storms, bare feet, warm mud and the crushed-glass stars spilling across the cooling sky. You can't learn these things anywhere, the grandma said. She said she planned to bring him up Victorian. It was better than "all this."

He was christened Che, right?

Grandma's wrist was pale and smooth as a flounder's belly. The sunny side of her arm was brown but she had dabbed the perfume on the white side—blue blood, that's what he thought, looking at the veins.

Christened? His father is a Jew, the grandma said. This fragrance is too old for her, she told the Bloomingdale's woman who raised a cautious eyebrow at the mother. The mother shrugged as if to say, What are you going to do? Too floral, Grandma Selkirk said without doubting she would know.

So it's Jay?

Grandma spun around and the boy's stomach gave a squishy sort of lurch. Why are you arguing with me? she whispered. Are you emotionally tone-deaf?

The salesgirl pursed her lips in violent sympathy.

Give me the Chanel, said Grandma Selkirk. While the salesgirl wrapped the perfume, Grandma Selkirk wrote a check. Then she took her pale kid gloves from the glass countertop. The boy watched as she drew them onto each finger, thick as eel skin. He could taste it in his mouth.

You want me to call him Che in Bloomingdale's, his grandma hissed, finally presenting the gift to the mother.

Shush, the mother said.

The grandma raised her eyebrows violently.

Go with the flow, said the mother. The boy petted her on the hip and found her soft, uncorseted.

The flow? The grandma had a bright, fright smile and angry light blue eyes. Go with the flow!

Thank you, the girl said, for shopping at Bloomingdale's.

The grandma's attention was all on the mother. Is that what Communists believe? Che, she cried, waving her gloved hand as in charades.

I'm not a Communist. OK?

The boy wanted only peace. He followed up behind, his stomach churning.

Che, Che! Go with the flow! Look at you! Do you think you could make yourself a tiny bit more ridiculous?

The boy considered his illegal mother. He knew who she was although no one would say it outright. He knew her the way he was used to knowing everything important, from hints and whispers, by hearing someone talking on the phone, although this particular event was so much clearer, had been since the minute she blew into the apartment, the way she held him in her arms and squeezed the air from him and kissed his neck. He had thought of her so many nights and here she was, exactly the same, completely different—honey-colored skin and tangled hair in fifteen shades. She had Hindu necklaces, little silver bells around her ankles, an angel sent by God.

Grandma Selkirk plucked at the Hindu beads. What is this? This is what the working class is wearing now?

I am the working class, she said. By definition.

The boy squeezed the grandma's hand but she snatched it free. Where's his father? They keep showing his face on television. Is he going with the flow as well?

The boy burped quietly in his hand. No one could have heard him but Grandma brushed at the air, as if grabbing at a fly. I called him Jay because I was worried for you, she said at last. Maybe it should have been John Doe. God help me, she cried, and the crowds parted before her. Now I understand I was an idiot to worry.

The mother raised her eyebrows at the boy and, finally, reached to take his hand. He was pleased by how it folded around his, soothing, comfortable. She tickled his palm in secret. He smiled up. She smiled down. All around them Grandma raged.

For this, we paid for Harvard. She sighed. Some Rosenbergs.

The boy was deaf, in love. By now they were out on Lexington Avenue and his grandma was looking for a taxi. The first cab would be theirs, always was. Except that now his hand was inside his true mother's hand and they were marsupials running down into the subway, laughing.

In Bloomingdale's everything had been so white and bright with glistening brass. Now they raced down the steps. He could have flown.

At the turnstiles she released his hand and pushed him under. She slipped off her pack. He was giddy, giggling. She was laughing too. They had entered another planet, and as they pushed down to the platform the ceiling was slimed with alien rust and the floor was flecked and speckled with black gum—so this was the real world that had been crying to him from beneath the grating up on Lex.

They ran together to the local, and his heart was pounding and his stomach was filled with bubbles like an ice-cream float. She took his hand once more and kissed it, stumbling.

The 6 train carried him through the dark, wire skeins unraveling, his entire life changing all at once. He burped again. The cars swayed and screeched, thick teams of brutal cables showing in the windowed dark. And then he was in Grand Central first time ever and they set off underground again, hand in hand, slippery together as newborn goats.

Men lived in cardboard boxes. A blind boy rattled dimes and quarters in a tin. The S train waited, painted like a warrior, and they jumped together and the doors closed as cruel as traps, chop, chop, chop, and his face was pushed against his mother's jasmine dress. Her hand held the back of his head. He was underground, as Cameron in 5D had predicted. They will come for you, man. They'll break you out of here.

In the tunnels between Times Square and Port Authority a passing freak raised his fist. Right On! he called.

He knew you, right?

She made a face.

He's SDS?

She could not have expected that—he had been studying politics with Cameron.

PL? he asked.

She sort of laughed. Listen to you, she said. Do you know what SDS stands for?

Students for a Democratic Society, he said. PL is Progressive Labor. They're the Maoist fraction. See, you're famous. I know all about you.

I don't think so.

You're sort of like the Weathermen.

I'm what?

I'm pretty sure.

Wrong fraction, baby.

She was teasing him. She shouldn't. He had thought about her every day, forever, lying on the dock beside the lake, where she was burnished, angel sunlight. He knew his daddy was famous too, his face on television, a soldier in the fight. David has changed history.

They waited in line. There was a man with a suitcase tied with bright green rope. He had never been anyplace like this before.

Where are we going? There was a man whose face was cut by lines like string through Grandma's beeswax. He said, This bus going to Philly, little man.

The boy did not know what Philly was.

Stay here, the mother said, and walked away. He was by himself. He did not like that. The mother was across the hallway talking to a tall thin woman with an unhappy face. He went to see what was happening and she grabbed his arm and squeezed it hard. He cried out. He did not know what he had done.

You hurt me.

Shut up, Jay. She might as well have slapped his legs. She was a stranger, with big dark eyebrows twisted across her face.

You called me Jay, he cried.

Shut up. Just don't talk.

You're not allowed to say shut up.

Her eyes got big as saucers. She dragged him from the ticket line and when she released her hold he was still mad at her. He could have run away but he followed her through a beat-up swing door and into a long passage with white cinder blocks and the smell of pee everywhere and when she came to a doorway marked facility, she turned and squatted in front of him.

You've got to be a big boy, she said.

I'm only seven.

I won't call you Che. Don't you call me anything.

Don't you say shut up.

OK.

Can I call you Mom?

She paused, her mouth open, searching in his eyes for something.

You can call me Dial, she said at last, her color gone all high.

Dial?

Yes.

What sort of name is that. It's a nickname, baby. Now come along. She held him tight against her and he once more smelled her lovely smell. He was exhausted, a little sick feeling.

What is a nickname?

A secret name people use because they like you.

I like you, Dial. Call me by my nickname too.

I like you, Jay, she said. They bought the tickets and found the bus and soon they were crawling through the Lincoln Tunnel and out into the terrible misery of the New Jersey Turnpike. It was the first time he actually remembered being with his mother. He carried the Bloomingdale's bag cuddled on his lap, not thinking, just startled and unsettled to be given what he had wanted most of all.

From the Hardcover edition.

There were no photographs of the boy's father in the house upstate. He had been persona non grata since Christmas 1964, six months before the boy was born. There were plenty of pictures of his mom. There she was with short blond hair, her eyes so white against her tan. And that was her also, with black hair, not even a sister to the blonde girl, although maybe they shared a kind of bright attention.

She was an actress like her grandma, it was said. She could change herself into anyone. The boy had no reason to disbelieve this, not having seen his mother since the age of two. She was the prodigal daughter, the damaged saint, like the icon that Grandpa once brought back from Athens—shining silver, musky incense—although no one had ever told the boy how his mother smelled.

Then, when the boy was almost eight, a woman stepped out of the elevator into the apartment on East Sixty-second Street and he recognized her straightaway. No one had told him to expect it.

That was pretty typical of growing up with Grandma Selkirk. You were some kind of lovely insect, expected to know things through your feelers, by the kaleidoscope patterns in the others' eyes. No one would dream of saying, Here is your mother returned to you. Instead his grandma told him to put on his sweater. She collected her purse, found her keys and then all three of them walked down to Bloomingdale's as if it were a deli. This was normal life. Across Park, down Lex. The boy stood close beside the splendid stranger with the lumpy khaki pack strapped onto her back. That was her blood, he could hear it now, pounding in his ears. He had imagined her a wound-up spring, light, bright, blonde, like Grandma in full whir. She was completely different; she was just the same. By the time they were in Bloomingdale's she was arguing about his name.

What did you just call Che? she asked the grandma.

His name, replied Grandma Selkirk, ruffling the boy's darkening summer hair. That's what I called him. She gave the mother a bright white smile. The boy thought, Oh, oh!

It sounded like Jay, the mother said.

The grandma turned sharply to the shopgirl who was busy staring at the hippie mother.

Let me try the Artemis.

Grandma Selkirk was what they call an Upper East Side woman—cheekbones, tailored gray hair—but that was not what she called herself. I am the last bohemian, she liked to say, to the boy, particularly, meaning that no one told her what to do, at least not since Pa Selkirk had thrown the Buddha out the window and gone to live with the Poison Dwarf.

Grandpa had done a whole heap of other things besides, like giving up his board seat, like going spiritual. When Grandpa moved out, Grandma moved out too. The Park Avenue apartment was hers, always had been, but now they used it maybe once a month. Instead they spent their time on Kenoza Lake near Jeffersonville, New York, a town of 400 where "no one" lived. Grandma made raku pots and rowed a heavy clinker boat. The boy hardly saw his grandpa after that, except sometimes there were postcards with very small handwriting. Buster Selkirk could fit a whole ball game on a single card.

For these last five years it had been just Grandma and the boy together and she threaded the squirming live bait to hook the largemouth bass and, also, called him Jay instead of Che. There were no kids to play with. There were no pets because Grandma was allergic. But in fall there were Cox's pippins, wild storms, bare feet, warm mud and the crushed-glass stars spilling across the cooling sky. You can't learn these things anywhere, the grandma said. She said she planned to bring him up Victorian. It was better than "all this."

He was christened Che, right?

Grandma's wrist was pale and smooth as a flounder's belly. The sunny side of her arm was brown but she had dabbed the perfume on the white side—blue blood, that's what he thought, looking at the veins.

Christened? His father is a Jew, the grandma said. This fragrance is too old for her, she told the Bloomingdale's woman who raised a cautious eyebrow at the mother. The mother shrugged as if to say, What are you going to do? Too floral, Grandma Selkirk said without doubting she would know.

So it's Jay?

Grandma spun around and the boy's stomach gave a squishy sort of lurch. Why are you arguing with me? she whispered. Are you emotionally tone-deaf?

The salesgirl pursed her lips in violent sympathy.

Give me the Chanel, said Grandma Selkirk. While the salesgirl wrapped the perfume, Grandma Selkirk wrote a check. Then she took her pale kid gloves from the glass countertop. The boy watched as she drew them onto each finger, thick as eel skin. He could taste it in his mouth.

You want me to call him Che in Bloomingdale's, his grandma hissed, finally presenting the gift to the mother.

Shush, the mother said.

The grandma raised her eyebrows violently.

Go with the flow, said the mother. The boy petted her on the hip and found her soft, uncorseted.

The flow? The grandma had a bright, fright smile and angry light blue eyes. Go with the flow!

Thank you, the girl said, for shopping at Bloomingdale's.

The grandma's attention was all on the mother. Is that what Communists believe? Che, she cried, waving her gloved hand as in charades.

I'm not a Communist. OK?

The boy wanted only peace. He followed up behind, his stomach churning.

Che, Che! Go with the flow! Look at you! Do you think you could make yourself a tiny bit more ridiculous?

The boy considered his illegal mother. He knew who she was although no one would say it outright. He knew her the way he was used to knowing everything important, from hints and whispers, by hearing someone talking on the phone, although this particular event was so much clearer, had been since the minute she blew into the apartment, the way she held him in her arms and squeezed the air from him and kissed his neck. He had thought of her so many nights and here she was, exactly the same, completely different—honey-colored skin and tangled hair in fifteen shades. She had Hindu necklaces, little silver bells around her ankles, an angel sent by God.

Grandma Selkirk plucked at the Hindu beads. What is this? This is what the working class is wearing now?

I am the working class, she said. By definition.

The boy squeezed the grandma's hand but she snatched it free. Where's his father? They keep showing his face on television. Is he going with the flow as well?

The boy burped quietly in his hand. No one could have heard him but Grandma brushed at the air, as if grabbing at a fly. I called him Jay because I was worried for you, she said at last. Maybe it should have been John Doe. God help me, she cried, and the crowds parted before her. Now I understand I was an idiot to worry.

The mother raised her eyebrows at the boy and, finally, reached to take his hand. He was pleased by how it folded around his, soothing, comfortable. She tickled his palm in secret. He smiled up. She smiled down. All around them Grandma raged.

For this, we paid for Harvard. She sighed. Some Rosenbergs.

The boy was deaf, in love. By now they were out on Lexington Avenue and his grandma was looking for a taxi. The first cab would be theirs, always was. Except that now his hand was inside his true mother's hand and they were marsupials running down into the subway, laughing.

In Bloomingdale's everything had been so white and bright with glistening brass. Now they raced down the steps. He could have flown.

At the turnstiles she released his hand and pushed him under. She slipped off her pack. He was giddy, giggling. She was laughing too. They had entered another planet, and as they pushed down to the platform the ceiling was slimed with alien rust and the floor was flecked and speckled with black gum—so this was the real world that had been crying to him from beneath the grating up on Lex.

They ran together to the local, and his heart was pounding and his stomach was filled with bubbles like an ice-cream float. She took his hand once more and kissed it, stumbling.

The 6 train carried him through the dark, wire skeins unraveling, his entire life changing all at once. He burped again. The cars swayed and screeched, thick teams of brutal cables showing in the windowed dark. And then he was in Grand Central first time ever and they set off underground again, hand in hand, slippery together as newborn goats.

Men lived in cardboard boxes. A blind boy rattled dimes and quarters in a tin. The S train waited, painted like a warrior, and they jumped together and the doors closed as cruel as traps, chop, chop, chop, and his face was pushed against his mother's jasmine dress. Her hand held the back of his head. He was underground, as Cameron in 5D had predicted. They will come for you, man. They'll break you out of here.

In the tunnels between Times Square and Port Authority a passing freak raised his fist. Right On! he called.

He knew you, right?

She made a face.

He's SDS?

She could not have expected that—he had been studying politics with Cameron.

PL? he asked.

She sort of laughed. Listen to you, she said. Do you know what SDS stands for?

Students for a Democratic Society, he said. PL is Progressive Labor. They're the Maoist fraction. See, you're famous. I know all about you.

I don't think so.

You're sort of like the Weathermen.

I'm what?

I'm pretty sure.

Wrong fraction, baby.

She was teasing him. She shouldn't. He had thought about her every day, forever, lying on the dock beside the lake, where she was burnished, angel sunlight. He knew his daddy was famous too, his face on television, a soldier in the fight. David has changed history.

They waited in line. There was a man with a suitcase tied with bright green rope. He had never been anyplace like this before.

Where are we going? There was a man whose face was cut by lines like string through Grandma's beeswax. He said, This bus going to Philly, little man.

The boy did not know what Philly was.

Stay here, the mother said, and walked away. He was by himself. He did not like that. The mother was across the hallway talking to a tall thin woman with an unhappy face. He went to see what was happening and she grabbed his arm and squeezed it hard. He cried out. He did not know what he had done.

You hurt me.

Shut up, Jay. She might as well have slapped his legs. She was a stranger, with big dark eyebrows twisted across her face.

You called me Jay, he cried.

Shut up. Just don't talk.

You're not allowed to say shut up.

Her eyes got big as saucers. She dragged him from the ticket line and when she released her hold he was still mad at her. He could have run away but he followed her through a beat-up swing door and into a long passage with white cinder blocks and the smell of pee everywhere and when she came to a doorway marked facility, she turned and squatted in front of him.

You've got to be a big boy, she said.

I'm only seven.

I won't call you Che. Don't you call me anything.

Don't you say shut up.

OK.

Can I call you Mom?

She paused, her mouth open, searching in his eyes for something.

You can call me Dial, she said at last, her color gone all high.

Dial?

Yes.

What sort of name is that. It's a nickname, baby. Now come along. She held him tight against her and he once more smelled her lovely smell. He was exhausted, a little sick feeling.

What is a nickname?

A secret name people use because they like you.

I like you, Dial. Call me by my nickname too.

I like you, Jay, she said. They bought the tickets and found the bus and soon they were crawling through the Lincoln Tunnel and out into the terrible misery of the New Jersey Turnpike. It was the first time he actually remembered being with his mother. He carried the Bloomingdale's bag cuddled on his lap, not thinking, just startled and unsettled to be given what he had wanted most of all.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Magnificent. . . . Alluring, unexpected, and intensely moving.” —The Boston Globe “Exhilarating. . . . Reading this novel is like peering at the human heart. . . . An adventure story for the modern, tormented soul.” —The New York Review of Books “A beautiful new novel. . . . Carey's stark language imbues the narrative with suspense, and his characters feel absolutely real. He's crafted an unconventional love story that's a striking portrait of the counterculture's dregs.”—People “Enthralling. . . . His close portrait of the relationship between one benighted woman and the child who depends on her is exquisite.” —The New York Times Book Review “His Illegal Self develops the kind of emotional impact that renders it enriching and satisfying . . . Carey is still the master . . . The genius of the novel is his portrayal of Che.”—Washington Post Book World“Carey’s often beautiful novel, one of his best recent works, has the bruising tang of all his fiction . . . The result is brilliantly vital . . . On the second page, we [are] caught by a voice, and held for the next two hundred pages . . . Funny and forlorn.”—James Wood, The New Yorker“Carey once again proves himself to be a master of perspective . . . Visceral and beautifully written . . . Carey reminds us of a time in America when people risked everything for a cause, for the dream of a better country. Ultimately, though, His Illegal Self is a love story–one between a young boy, longing for a love from his past, and a woman whose unexpected love for a boy forever alters her fate.”—San Francisco Chronicle“Carey is a prose Pied Piper, a dazzling stylist whose work possesses mythic elements. Once he launches into a tale, he’s always worth following . . . Carey enters fully into the character of Che, who is neither snarky nor cloying [but] utterly compelling . . . The story moves along at a thriller’s pace.”—Miami Herald“Reading this novel is like peering at the human heart, at the world itself, through the distorted precision of a magnifying glass–one carried in the pocket of a seven-year-old boy . . . One of the wonders of Carey’s work is that his great, urgent narratives, so turbulent, so dark, so grand, are at the same time animated by such conscious and playful craft, as well as by a profound comic awareness . . . His Illegal Self, like his other work, is an adventure story for the modern, tormented soul.”—Cathleen Schine, New York Review of Books“Carey is a thoroughly modern writer, smashing genre boundaries, ranging in tone from wild comedy to grim tragedy, viewing the past with a decidedly contemporary eye and firmly placing late 20th century adventures in social and cultural context. This breadth of experience and abilities enriches Carey’s latest novel.’”–Los Angeles Times Book Review “Carey has a matchless imagination. His novels are hallucinogenic in their visual intensity and breathtaking in their Dickensian plot twists . . . The supreme gift to the reader is Carey’s portrait of a scared little boy who becomes brave. [It’s] the best reason to pick up this novel, sit down and not get up until it’s done.”–Seattle Times“Carey’s gift for creating voices is so real that we can almost hear the words. This gift adds to our deep involvement with his characters, who are among the most sympathetic collection of ruffians, losers and damaged human beings in contemporary literature . . . He has once again created an elegant, touching and often funny story.” –Cleveland Plain Dealer“His Illegal Self [left] me brimming with admiration . . . What’s evident right from the start here is how vividly, and tenderly Carey has inhabited his central character . . . There are times when his ability to empathise with a small child recalls, and comes close to matching, David Copperfield . . . The result is a richly absorbing novel which can be relished for the beauties of its prose and the pertinence of its themes, as well as for the progressively taut pull that it exerts on the emotions.”–Sunday Telegraph (U.K.) “His Illegal Self is a wonderful novel, full of hard-won truths, which nevertheless leaves you with a warm and fuzzy feeling of immense satisfaction .”–The Evening Standard (U.K.)“Che is as convincing a child as any I have found in the pages of a book: beady as a boy scout; innocent and yet so knowing; brimming with watery nostalgia for states he has never even known.”–The Observer (U.K.)“Carey seems to invent himself fresh each time he publishes, finding a different (but always compelling and deeply idiosyncratic) narrative voice, filling each sentence with charm and skill, and utterly sucking a reader in. Here, he has done all that again . . . Carey’s achievement here, though, is of a larger order as well, in the way he identifies, creates, rounds out and refines for us the character of Che.”–Canberra Times (Australia)“A beautiful and emotionally compelling novel . . . There is in this book a fascinating and deeply intelligent evocation of late ‘60s, early ‘70s period detail, but at its core His Illegal Self is an ancient and magnificently eerie fairy tale, about a child wise beyond his years, stolen away to the forest, undergoing every kind of mortal trial, and surviving, in a surprising state of luminous grace.”–O Magazine“A psychologically astute and diabolically suspenseful novel . . . Carey has a gift for bringing to creepy-crawly and blistering life Australia’s jungle and desert wilds. His latest spectacularly involving and supremely well made novel of life on the edge begins in New York [and] ends up in Australia . . . Carey’s unique take on the conflict between the need to belong and the dream of freedom during the days of rage over the Vietnam War is at once terrifying and mythic.”–Booklist“Peter Carey is one of the great writers in English now. This book is further proof, a book in which he’s created a little boy who is neither too precious nor too wise, a little boy on a sad hard trip with his eyes wide open, watching everything and everyone around him. He makes you think of your own past life and all you felt when you were a kid being played upon and moved about by the adults of the world. This book is another triumph, among Carey’s other wonderful books. The man can write. He seems capable of anything.”–Kent Haruf“Carey’s mastery of tone and command of point of view are very much in evidence in his latest novel, which is less concerned with period-piece politics than with the essence of identity . . . This isn’t the first fictional work to explore the militant radical underground of the late 1960s and early ’70s, but it may well be the best.”–Kirkus Reviews (starred)

Descriere

Raised in isolated privilege by his New York grandmother, Che is the precocious son of radical student activists at Harvard in the late 1960s. Yearning for his famous outlaw parents, he bravely confronts his life, learning that nothing is what it seems.