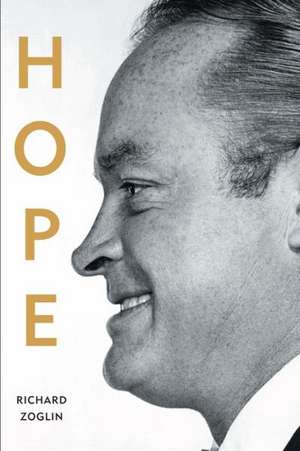

Hope: Entertainer of the Century

Autor Richard Zoglinen Limba Engleză Hardback – 24 feb 2015

Born in 1903, and until his death in 2003, Bob Hope was the only entertainer to achieve top-rated success in every major mass-entertainment medium, from vaudeville to television and everything in between. He virtually invented modern stand-up comedy. His tours to entertain US troops and patriotic radio broadcasts, along with his all-American, brash-but-cowardly movie character, helped to ease the nation's jitters during the stressful days of World War II. He helped redefine the very notion of what it means to be a star: a savvy businessman, pioneer of the brand extension (churning out books, writing a newspaper column, hosting a golf tournament), and public-spirited entertainer whose Christmas military tours and tireless work for charity set the standard for public service in Hollywood. But he became a polarizing figure during the Vietnam War, and the book sheds new light on his close relationship with President Richard Nixon during those embattled years.

Bob Hope is a household name. However, as Richard Zoglin shows in this revelatory biography, there is still much to be learned about this most public of figures, from his secret first marriage and his stint in reform school, to his indiscriminate womanizing and his ambivalent relationship with Bing Crosby and Johnny Carson. Hope could be cold, self-centered, tight with a buck, and perhaps the least introspective man in Hollywood. But he was also a dogged worker, gracious with fans, and generous with friends.

"Hope" is both a celebration of an entertainer whose vast contribution has never been properly appreciated, and a complex portrait of a gifted but flawed man, who, unlike many Hollywood stars, truly loved being famous, appreciated its responsibilities, and handled celebrity with extraordinary grace.

Preț: 274.16 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 411

Preț estimativ în valută:

52.47€ • 54.71$ • 43.60£

52.47€ • 54.71$ • 43.60£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781410475213

ISBN-10: 1410475212

Pagini: 806

Dimensiuni: 145 x 218 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.9 kg

Ediția:Text mare

Editura: Thorndike Press Large Print

ISBN-10: 1410475212

Pagini: 806

Dimensiuni: 145 x 218 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.9 kg

Ediția:Text mare

Editura: Thorndike Press Large Print

Notă biografică

Richard Zoglin is a contributor to Time magazine and the author of Hope: Entertainer of the Century, Comedy at the Edge: How Stand-up in the 1970s Changed America, and Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show. A native of Kansas City, Zoglin currently lives in New York City.

Extras

Hope

On a balmy October morning in 2010, one hundred people were gathered on a dock in Battery Park at the foot of Manhattan Island. They were a well-dressed group—the men in jackets and ties, the women in business suits. Many were quite old and needed help climbing into the boat that had been chartered to ferry them across New York Harbor to Ellis Island. Once there, they made their way to the second floor of the cavernous Immigration Museum building, where rows of chairs had been set up in a long, book-lined room, which was about to be dedicated as the Bob Hope Memorial Library.

Linda Hope, the late comedian’s seventy-one-year-old daughter, stepped to the microphone to emcee the ceremony. She introduced the smattering of celebrities on hand—actress Arlene Dahl, baseball legend Yogi Berra, two US congressmen—and several clip reels highlighting Bob’s life and career: his childhood years in England, where he was born in 1903, and Cleveland, Ohio, where he and his family emigrated when he was four and a half; scenes from his movies and TV shows; excerpts from his tours to entertain US troops around the globe. His granddaughter, Miranda, accompanying herself on guitar, sang a folk ballad called “Immigrant Eyes.” Dick Cavett popped up from the audience to tell a couple of impromptu stories about Hope, whom he had befriended in the comedian’s later years. Michael Feinstein, the cabaret singer and musical archivist, closed the event with a wistful solo rendition of Bob’s theme song, “Thanks for the Memory.”

It was another chapter in what has surely been the most determined campaign of legacy building in Hollywood history. A few months before the Ellis Island ceremony, Hope’s family and friends gathered in Washington, DC, to inaugurate a new Hope-centric exhibit on political humor at the Library of Congress, where the comedian’s voluminous letters and papers are stored. A year earlier, the Hope legacy tour made a stop on the deck of the USS Midway in San Diego Harbor to mark the introduction of a postage stamp bearing Hope’s likeness. Memorials to Hope have proliferated across the American landscape. You can walk down streets named for Bob Hope in El Paso, Texas, Miami, Florida, and Branson, Missouri; cross the Cuyahoga River on the Hope Memorial Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio; and bypass the congestion at Los Angeles International by flying into the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, California. Hope’s name is memorialized on hospitals, theaters, chapels, schools, performing arts centers, and American Legion posts from Miami to Okinawa. The US Air Force named a transport plane for him, and the Navy christened a cargo ship in his honor. Bob Hope Village, in Shalimar, Florida, provides a home for retired members of the Air Force and their surviving spouses. The World Golf Hall of Fame, in St. Augustine, Florida, features an exhibit celebrating Hope’s passion for the game, “Bob Hope: Shanks for the Memory.” A dozen colleges offer scholarships in Hope’s name. Another dozen organizations give out awards in his honor, among them the Air Force’s annual Spirit of Hope Award and the Bob Hope Humanitarian Award, presented by the Academy of Television Arts & Science.

His punchy, two-syllable name, so emblematic of the optimistic American spirit; the unmistakable profile, with its jutting chin and famously ski-slope-shaped nose; the indelible images of Hope performing for throngs of cheering GIs in World War II and Vietnam—it was once impossible to imagine a time when the first question that needed to be answered about the most popular comedian in American history would be: Who was Bob Hope, and why did he matter?

By the time he died—on July 27, 2003, two months after his hundredth birthday—Hope’s reputation was already fading, tarnished, or being actively disparaged. He had, unfortunately, stuck around too long. The comedian of the century, who began his vaudeville career in the 1920s and was still headlining TV specials in the 1990s, continued performing well into his dotage, and a younger generation knew him mainly as a cue-card-reading antique, cracking dated jokes about buxom beauty queens and Gerald Ford’s golf game. “World’s Last Bob Hope Fan Dies of Old Age,” the Onion’s fake headline announced a year before his death. Writer Christopher Hitchens expressed the disaffection of many of the baby-boom generation in an online dismissal of Hope just a few days after his passing: “To be paralyzingly, painfully, hopelessly unfunny is a serious drawback, even lapse, in a comedian. And the late Bob Hope devoted a fantastically successful and well-remunerated lifetime to showing that a truly unfunny man can make it as a comic. There is a laugh here, but it is on us.”

Hope never recovered from the Vietnam years, when his hawkish defense of the war, close ties to President Nixon (who actively courted Hope’s help in selling his Vietnam policies to the American people), and the country-club smugness of his gibes about antiwar protesters and long-haired hippies, all made him a political pariah for the peace-and-love generation. His tours to entertain US troops during World War II had made him a national hero. By the turbulent 1960s, he was a court-approved jester, the Establishment’s comedian—hardly a badge of honor in an era when hipper, more subversive comics, from Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce to George Carlin and Richard Pryor, were showing that stand-up comedy could be a vehicle for personal expression, social criticism, and political protest. Even before Hope became a doddering relic, he had become an anachronism.

Yet the scope of Hope’s achievement, viewed from the distance of a few years, is almost unimaginable. By nearly any measure, he was the most popular entertainer of the twentieth century, the only one who achieved success—often No. 1–rated success—in every major genre of mass entertainment in the modern era: vaudeville, Broadway, movies, radio, television, popular song, and live concerts. He virtually invented stand-up comedy in the form we know it today. His face, voice, and stage mannerisms (the nose, the lopsided smile, the confident, sashaying walk, and the ever-present golf club) made him more recognizable to more people than any other entertainer since Charlie Chaplin. A tireless stage performer who traveled the country and the world for more than half a century doing live shows for audiences in the thousands, he may well have been seen in person by more people than any other human being in history.

His achievements as an entertainer, however, only hint at the breadth and depth of his impact. For the way he marketed himself, managed his celebrity, cultivated his brand, and converted his show-business fame into a larger, more consequential role for himself on the public stage, Bob Hope was the most important entertainer of the century. Viewed from the largest historical perspective—the way he intersects with the grand themes of the century, from the Greatest Generation’s crusade to preserve democracy in World War II, to the social, political, and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s—one could argue, without too much exaggeration, that he was the only important entertainer.

His life almost perfectly spanned the century, and to recount his career is to recapitulate the history of modern American show business. He began in vaudeville, first as a song-and-dance man and then as an emcee and comedian, working his way up from the amateur shows of his Cleveland hometown to headlining at New York’s legendary Palace Theatre. He segued to Broadway, where he costarred in some of the era’s classic musicals, appeared with legends such as Fanny Brice and Ethel Merman, and introduced standards by great American composers such as Jerome Kern and Cole Porter. Hope became a national star on radio, hosting a weekly comedy show on NBC that was America’s No. 1–rated radio program for much of the early 1940s and remained in the top five for more than a decade.

He came relatively late to Hollywood, making his feature-film debut, at age thirty-four, in The Big Broadcast of 1938, where he sang “Thanks for the Memory”—which became his universally identifiable, infinitely adaptable theme song and the first of many pop standards that, almost as a sideline, he introduced in movies. With an almost nonstop string of box-office hits such as The Cat and the Canary, Caught in the Draft, Monsieur Beaucaire, The Paleface, and the popular Road pictures with Bing Crosby, Hope ranked among Hollywood’s top ten box-office stars for a decade, reaching the No. 1 spot in 1949.

Hope brought a new kind of character and attitude to the movies. He was the brash but self-mocking wise guy, a braggart who turned chicken in the face of danger, a skirt chaser who quivered like Jell-O when the skirt chased back. “I grew up loving him, emulating him, and borrowing from him,” said Woody Allen, one of the few comics to acknowledge how much he was influenced by Hope—though nearly everyone was. Hope played variations on his cowardly character in spy comedies, ghost stories, costume epics, Westerns—but always with a winking nod to the audience, an acknowledgment that he was an actor playing a role. Especially in his interplay with Crosby in the Road films, Hope often spoke directly to the camera or stepped out of character to make cracks about the studio, his career, and his Hollywood friends. This improvisational, fourth-wall-breaking spirit was a radical break from the stylized sophistication of the 1930s romantic comedies, or the artifice of other vaudeville comics who transitioned into movies, such as W. C. Fields or the Marx Brothers. And it perfectly met the psychological needs of a nation at a time of war and world crisis. As the newsreels broadcast scenes of thundering European dictators, jackbooted military troops, and docile, mindlessly cheering crowds, Hope’s humor was both an escape and an affirmation of the American spirit: feisty, independent, indomitable.

When television came in, Hope was there too. Others, such as Milton Berle, preceded him. But after starring in his first NBC special on Easter Sunday in 1950, Hope began an unparalleled reign as NBC’s most popular comedy star that lasted for nearly four decades. Other comedians who made the move into television—Berle, Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Jackie Gleason, Danny Thomas, even Lucille Ball—had their heyday on TV and then faded; Hope alone remained a major star headlining top-rated TV shows well into his eighties. His 1970 Christmas special from Vietnam was the most watched television program of all time up to that point, seen in a now-unthinkable 46.6 percent of all TV homes in the country. (The final episodes of Dallas, M*A*S*H, and Roots are the only entertainment shows ever to beat it.)

That would have been enough for most performers, but not Hope. Along with his radio, TV, and movie work, he traveled for personal appearances at a pace matched by no other major star. He was just one of many performers who went overseas on USO-sponsored tours to entertain the troops during World War II. Unlike most of the others, he didn’t stop when the war ended. Starting with a trip to Berlin during a Cold War crisis in 1948, he launched an annual tradition of entertaining US troops around the world at Christmas—in wartime and peacetime, from forlorn outposts in Alaska to the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. Stateside, he was just as indefatigable, making as many as 250 personal appearances a year, manning the microphone at charity benefits, trade shows, state fairs, testimonial dinners, hospital dedications, Boy Scout jamborees, Kiwanis Club luncheons, and seemingly any event that could pack a thousand people into a ballroom on the promise that Bob Hope would be there to deliver the one-liners.

On a podium, no one could touch him. He was host or cohost of the Academy Awards ceremony a record nineteen times—the first in 1940, when Gone With the Wind was the big winner, and the last in 1978, when Star Wars and Annie Hall were the hot films. His suave unflappability—no one ever looked better in a tuxedo—and tart insider wisecracks (“This is the night when war and politics are forgotten, and we find out who we really hate”) helped turn a relatively low-key industry dinner into the most obsessively tracked and massively watched event of the Hollywood year.

The modern stand-up comedy monologue was essentially his creation. There were comedians in vaudeville before Hope, but they mostly worked in pairs or did prepackaged, jokebook gags that played on ethnic stereotypes and other familiar comedy tropes. Hope, working as an emcee and ad-libbing jokes about the acts he introduced, developed a more freewheeling and spontaneous monologue style, which he later honed and perfected in radio. To keep his material fresh, he hired a team of writers and told them to come up with jokes about the news of the day—presidential politics, Hollywood gossip, California weather, as well as his own life, work, travels, golf game, and show-business friends.

This was something of a revolution. When Hope made his debut on NBC in 1938, the popular comedians on radio all inhabited self-contained worlds, playing largely invented comic characters: Jack Benny’s effete tightwad, Edgar Bergen and his uppity dummy, Charlie McCarthy, the daffy-wife/exasperated-husband interplay of George Burns and Gracie Allen. Hope’s monologues brought something new to radio: a connection between the comedian and the outside world.

Hope was not the first comedian to do jokes about current events. Will Rogers, the Oklahoma-born humorist who offered folksy and often pointed commentary on politics and the American scene, achieved huge popularity in vaudeville, movies, and radio in the 1920s and 1930s, before his death in a plane crash in 1935. Fred Allen, the frog-voiced radio satirist, was aiming acerbic and literate barbs at the potentates of both Washington and his own network while Hope was still apprenticing. But Hope was the first to combine topical subject matter with the rapid-fire gag rhythms of the vaudeville quipster. His monologues became the template for Johnny Carson and nearly every late-night TV host who followed him, and the foundation stone for all stand-up comics, even those who rebelled against him.

Hope wasn’t a political satirist. His jokes never hit hard, cut deep, or betrayed any political viewpoint. Mostly they took personalities and events from the news and lampooned them for superficial things, or with clever wordplay—an ironic juxtaposition or unexpected twist or jokey hyperbole. “Not much has been happening back home,” Hope told a crowd of servicemen after the 1960 presidential election. “Hawaii and Alaska joined the union, and the Republicans left it.” He poked fun at new California governor Ronald Reagan for his Hollywood pedigree, not his conservative politics: “California’s back to a two-party system: the Democrats and the Screen Actors Guild.” When Bobby Kennedy was thinking of running for president, Hope joked about the candidate’s growing brood of kids: “He may win the next election without leaving the house.” On hot-button issues such as gay rights, Hope’s gags amiably skirted any potential land mines: “In California homosexuality is legal. I’m getting out before they make it mandatory.”

He was the first comedian to openly acknowledge that he used writers—as many as a dozen at a time, turning out hundreds of potential jokes for each monologue. He saved them all, the keepers and the castoffs, in a fireproof vault in the office wing of his home in Toluca Lake, California—more than a million of them by the end of his career, all filed alphabetically according to subject matter (“Fairs, Fans, Finance, Firemen, Fishing . . .”). The jokes were rarely memorable, trenchant, or even very funny, and his dependence on writers would later be scorned by younger comedians, who mostly wrote their own material. Yet the jokes were always the weakest part of his act; his impeccable delivery is what put them across. The lamest formula gags could get laughs through the sheer force of his style and stage presence: the confident manner, the rat-a-tat pace and clarion tone of his voice, the perfect weight and balance given to each word, the way he barreled through a punch line and began the next setup (“But I wanna tell ya . . .”) until the laughter caught up with him—a technique that both bullied the audience into laughing and congratulated it for keeping up.

This was more than just the triumph of style over substance. Like the great pop and jazz singers of the pre-rock era, who performed songs written by others (before the Beatles came along, and singers had to become songwriters too), Hope was not a creator but a great interpreter. He didn’t necessarily say funny things, but he said them funny. Larry Gelbart, who wrote for Hope on radio for four years, before creating the hit TV series M*A*S*H, recalled watching Hope onstage at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre in 1948 and being surprised at the belly laughs he got for a joke whose punch line mentioned a motel.

“Do you think anybody here knows what the word motel means?” Gelbart asked the pretty British girl he was with.

“No,” she replied.

“Then why were you laughing?”

“Because he’s so funny.”

Hope sold an attitude: brash, irreverent, upbeat. He was a product of Middle America—“the unabashed show-off, the card, the snappy guy who gets off hot ones at shoe salesmen’s conventions while they’re waiting for the girls to show up,” as humorist Leo Rosten once put it—who eased the country’s anxieties through complex and difficult times. The message of his comedy was that no issue was so troubling, no public figure so imposing, no foreign threat so intimidating, that it couldn’t be cut down to size by some good old American razzing. Hope’s comedy punctured pomposity and fed a healthy skepticism of politics and public figures. It helped Americans process changing mores, from new roles for women during World War II to the counterculture revolution of the 1960s. If the jokes were sometimes corny, even reactionary, Hope could be excused. He transcended comedy; he was the nation’s designated mood-lifter. No one else could perform that role; few even tried. Comedians for years did impressions of Jack Benny, Groucho Marx, George Burns, and other classic clowns. Almost no one did Bob Hope. His ordinariness was inimitable.

• • •

The machinelike impersonality of Hope’s comedy mirrored the impenetrability of Hope the man. Even to intimates and people who worked with him for years, he remained largely a cipher. He was not given to introspection or burdened with inner angst. He was the last person in Hollywood one could imagine walking into a therapist’s office. He never read books or went to art museums, unless he was dedicating the building. “Bob had no intellectual curiosity,” said a younger writer who befriended him in his later years. “If it didn’t concern him, he didn’t care.” He had just one hobby, golf—which provided him with access to presidents, corporate titans, and other power brokers, as well as the material for endless jokes. He authored several memoirs, but all were ghostwritten and filled with one-liners rather than revelations about his inner life.

In public he could be charming, charismatic, and surprisingly approachable. Always attentive to fans, he rarely turned down an autograph request or failed to acknowledge a compliment. He had a photographic memory for names and faces—people he had met at fund-raising events or on the golf course, even the officers of army units he had once entertained. In social gatherings, the room would galvanize around him. “Everybody came to attention when he walked into the room or when they were engaged in conversation with him,” said Sam McCullagh, his former son-in-law. “He had a bright spirit—the way you say a saxophonist has a bright sound. The room lit up. His personality beckoned you.”

He was funny even without his writers. Unlike some comedians, driven by insecurity and a need for constant attention, Hope was not always “on,” rattling off one-liners in normal conversation. Yet he had a natural, unforced, possibly brilliant wit. His writers could see it in the material they didn’t write for him. “He was funnier than the monologues,” said Larry Gelbart. “He was original. He would rather die than call you by your real name—he called me Fringe because I used to have a very short haircut. He spoke the way Johnny Mercer wrote lyrics, always colorful, with a twist.”

His TV and radio audiences could glimpse it in the ad-libs that popped so easily from him when slipups occurred on the air—the wisecrack after a fumbled line or missed cue, which made those now-clichéd “blooper reels” funnier than the sketches they supposedly ruined. Friends and colleagues saw it in his ability to respond in the moment, in ways no script could predict. A Times of London reader, in a letter to the editor a few days after Hope’s death, recalled sitting behind Hope on a shuttle flight between New York and Boston in the 1960s, when hijackings to Cuba were in the news. Though it was an utterly routine one-hour flight, a starstruck stewardess fawned over her celebrity passenger. “Mr. Hope,” she cooed, “I hope you will save your ticket and boarding pass, because I mean to make this one of your most memorable airline flights ever.” Hope’s dry response: “My God, not Havana again.” A family member marveled at Hope’s opening line at a luncheon for the Catholic diocese of St. Louis in the early 1970s. The bishop who was to introduce Hope launched unexpectedly into a long comedy routine of his own, cracking up the room. Finally the prelate wrapped up his monologue and introduced the comedian who was the guest of honor. Hope walked to the microphone and began soberly, “Let us pray.”

Yet his personality had an essential coldness, a wall that prevented outsiders from getting behind the flip, impenetrable surface. For the writers who worked for him, he was an affable, good-humored boss, one of the boys. But the narcissism could be oppressive. He expected them to be on call at any hour of the day or night; he was known for his late-night phone calls, to suggest a new topic for jokes he needed by morning or simply to repeat a funny story he had just heard (often a dirty one). “Once you worked for Hope, you were his property, and just on loan to the rest of the world,” said Hal Kanter, who wrote for him off and on for forty years. He was notoriously tight with a dollar, a boss who could complain about reimbursing employees for the cost of a cab ride. Yet he was generous with relatives and friends who were down on their luck, many of whom he quietly helped out financially for years.

He surrounded himself with a battalion of lawyers, agents, public relations men, and assistants of various kinds, who helped manage his public image and protected him from the rough edges of everyday life. Once he called up a neighborhood movie theater and asked what time the feature started. The theater manager replied, “What time can you get here?” He never wore a watch—others could tell Bob Hope the time. He never apologized and rarely said thank you. His longtime publicist Frank Liberman recalled Hope’s unhappiness at the lack of press coverage for a special he was set to host at Madison Square Garden in the 1960s. Finally Liberman landed Hope a coveted interview with the New York Times. The star’s only response: “Now you’re talkin’.”

For journalists, he was a frustrating interview, glib and stubbornly unrevealing. J. Anthony Lukas, who wrote a profile of Hope for the New York Times Magazine in 1970, at the height of the embattled Vietnam years, recounted a telling anecdote from one of Hope’s publicists. A magazine reporter, interviewing Hope on an airplane, grew increasingly frustrated with his flip responses to her questions about what motivated him as a performer. When she got up to go to the bathroom, the publicist took Hope aside and told him, “Bob, this gal comes from New York, where they’re very big on psychoanalysis. The only way to stop her is to tell her you work so hard because you’re the fifth of seven sons and you had to compete for your mother’s attention.” When the reporter returned, Hope repeated the publicist’s answer almost word for word. The reporter smiled happily, and her story wound up quoting his revelation—made “in a rare moment of introspective analysis.”

It’s not just that Hope was closed off. He seemed to regard the details of his biography and private life as fungible particulars, to be shaped and rewritten as needed for public consumption. He had one of the longest-running and most celebrated marriages in Hollywood—for sixty-nine years, to former nightclub singer Dolores Reade. But he was a lifelong womanizer, carrying on a string of extramarital affairs that were an open secret to friends and colleagues, but largely kept under wraps by his entourage and the press. He had a secret, short-lived first marriage, to his former vaudeville partner, which he never publicly acknowledged. And he almost certainly fudged the date and place of his marriage to Dolores—which, since there is no record of it, some family members suspected may never have taken place at all.

Yet it was, in its fashion, a good marriage. Bob depended on Dolores, a smart, strong-willed Catholic, for counsel, support, and the proper image of Hollywood domesticity. She ran the household, raised their four adopted children, and organized his social life. Hope was a playful, not uncaring, but distant and frequently absent father—a fleeting presence at family dinners, who would typically arrive late and dash off early, always running to appointments. His children had fond memories of their limited time with him, but also varying degrees of trouble coping with the burden of having Bob Hope as a father. It may have weighed most heavily on his youngest daughter, Nora, who broke with the family entirely after a dispute with her mother in the 1980s and remained estranged for the rest of her parents’ lives.

If any of this caused Hope serious angst, he kept it well hidden. A Los Angeles Times profile in 1941 called him “the world’s only happy comedian,” and it may not have been far from the truth. He was energized by performing, never seemed stressed, and kept up an exhausting work schedule well into his eighties. He refreshed himself with frequent catnaps, daily massages, and long walks every night before he went to bed, no matter how late the hour or unfamiliar the terrain (usually with a companion—and in later years a golf club for protection). Though one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood, he had a relatively unpretentious lifestyle, raising his family not in the ritzy enclaves of Beverly Hills or Bel Air, but in the San Fernando Valley bedroom community of Toluca Lake. He had a second home in the desert resort of Palm Springs, but it was a relatively modest three-bedroom retreat until the 1970s, when Dolores oversaw the construction of a giant, modernist showplace, with a dome-shaped roof that reminded many of the TWA terminal at New York’s JFK Airport.

He was on a first-name basis with presidents and generals, corporate leaders, and business titans. But his closest friends were the people he worked with—writers, old cronies from Cleveland, former vaudevillians, businessmen who joined him for golf and supplied him with clothes and other freebies. Until his later years he drove his own car—not a fancy Mercedes, but one of the middle-class Chryslers or Buicks given to him by his TV sponsors. Despite a busier travel schedule than practically any other star in Hollywood, he didn’t have a private plane until late in life, when his friend and San Diego Chargers owner Alex Spanos loaned him one. After seeing how much it cost to maintain, Hope gave it back.

To many he seemed hopelessly shallow: a gleaming perpetual-motion machine with a missing piece at the center. “Deep down inside, there is no Bob Hope,” writer Martin Ragaway once said. “He’s been playing Bob Hope for so long that everything else has been burned out of him. The man has become his image.” But what seemed shallowness was merely a sign of how effectively Hope was able to guard his private life, and the almost superhuman intensity of focus on his public one. His manager, Elliott Kozak, liked to say that every morning Bob Hope would get up, look in the mirror, and say to himself, “What can I do today to further my career?” That relentless dedication to his own stardom allowed Hope to virtually redefine the notion of stardom in the twentieth century. Indeed, there is hardly an element of our modern celebrity culture that Bob Hope did not invent, pioneer, or help to popularize. He was largely responsible, in the age of celebrity, for setting the parameters of what it means to be a celebrity:

THE STAR AS BUSINESSMAN. Like nearly every movie star of the 1930s and 1940s, Hope was initially a salaried employee, signing regular contracts with his studio, Paramount Pictures, for a specified number of films per year at a fixed fee. But in the mid-1940s, when he was churning out box-office hits like clockwork, Hope set up his own production company, so that he could have an ownership stake in his movies and keep more of the profits. A few years later he made a similar deal with NBC, becoming the producer of his own TV specials and charging the network a license fee for them—enabling him to own his shows in perpetuity. Hope wasn’t the first Hollywood star to become an entrepreneur of his own career; he patterned his Paramount deal after one that his friend Bing Crosby had made with the same studio a few years earlier. But his business arrangements were the most successful and highly publicized of his day, and a model for the production companies and packaging deals that have become routine for nearly every major star in Hollywood.

Hope’s business acumen became part of his legend. By the late 1940s he was making more than $1 million a year, when that was real money. He invested it shrewdly, first in oil and then in California real estate, buying up huge parcels of land in the San Fernando Valley and elsewhere; at one time he was reputed to be the largest private landowner in the state of California. Fortune magazine in 1968 estimated his net worth at over $150 million—making him the richest person in Hollywood, wealthier even than studio moguls. He was forever complaining that such estimates were too high, and he may have been right. After Forbes magazine put him on its list of America’s four hundred richest people in 1982, he challenged the magazine to prove it and got his net worth downgraded from over $200 million to a measly $115 million. Still, Hope was rich, a canny businessman, and a key figure in the gradual shift of power in Hollywood away from the studio and network moguls and toward the stars who kept them in business, and who began taking control of their own financial destiny.

THE STAR AS BRAND. Hope was voracious in seeking out new audiences, marketing his fame across what would today be called multiple platforms. He had been a movie and a radio star for only three years when he published his first book—a jokey, illustrated memoir (penned largely by his gag writers) called They Got Me Covered. It was a surprise bestseller, and Hope went on to author or coauthor eleven more books, including another, more substantial autobiography, memoirs of his travels during World War II and Vietnam, and books about golf and his encounters with presidents. He promoted all of them tirelessly, in personal appearances around the country, on his own TV specials, and in guest spots on other TV shows—an early demonstration of the power of show-business synergy.

He was Hollywood’s inventor of the brand extension. Along with the books, he had a daily syndicated newspaper column (ghosted, as always, by his writers), which began with dispatches from his World War II tours and continued for eight years afterward, into the early 1950s. He brought his name, prestige, and showbiz connections to a struggling Palm Springs golf tournament, renamed it the Bob Hope Desert Classic, and turned it into the most star-studded pro-am event on the PGA Tour. He was the star of a comic book: The Adventures of Bob Hope, launched in 1950 by DC Comics and published quarterly for the next eighteen years. He even had his own logo—the familiar line-drawn caricature of his concave-shape profile, instantly recognizable from Boston to Bangkok.

THE STAR AS PUBLIC CITIZEN. Hope was far from the only Hollywood star who used his talents to raise money for charitable causes. But no one else pursued his public-service mission so fervently or made it such an integral part of his image. He was awarded the first of five honorary Oscars in 1941, for being “the man who did the most for charity.” He was the most celebrated of the stars who toured the Pacific and European theaters to entertain the troops during World War II. Back home after the war, he became a ubiquitous fund-raiser, host of charity events, and supporter of patriotic causes, securing his reputation as Hollywood’s most tireless do-gooder.

All this had a careerist aspect, of course. Hope sincerely loved entertaining the troops, and it fed the patriotic pride of an immigrant who had lived a classic Horatio Alger success story. But his troop shows also provided him with huge, easy-to-please audiences, lofty TV ratings, and boundless good publicity. Still, no cynical view of his motives can diminish the impact that Hope had in setting a standard for public service in Hollywood. “Playing the European theater, or any theater of war, is a good thing for actors,” he wrote in I Never Left Home, the memoir of his World War II travels. “It’s a way of showing us that there’s something more important than billing; or how high your radio [rating] is; or breaking the house record in Denver.” Hope showed by example that Hollywood stars have an opportunity, even an obligation, to do more than just make movies, sign autographs, and buy oceanfront estates in Malibu. They can give back, do good, use their fame to make an impact in the public arena.

Hope’s particular causes and conservative political views, of course, were not the same as those of many of the stars who followed his example. But he opened the way for celebrities to have causes and political views—to work for endangered whales or starving children in Africa or hurricane victims in Louisiana. They may not acknowledge or even realize it, but a direct generational line connects Bob Hope to the globe-trotting activism of Angelina Jolie and George Clooney, Madonna and Oprah Winfrey. Hope made it safe for celebrities to be taken seriously as public citizens.

THE STAR AS INSPIRATION. Even as he golfed with presidents, entertained royalty, and became one of the most famous people in the world, Hope maintained an unusually powerful and personal connection with his fans. This relationship was qualitatively different from that of most stars and their public, an intimate link that illustrated the symbolic role celebrities can play in the inner lives of their fans. “It is painfully obvious to us that our communications with our celebrated favorites is all one-way,” wrote Richard Schickel in his book about fame, Intimate Strangers. “They send (and send and send) while all we do is receive (and receive and receive). They do not know we exist as individuals; they see us only as the components of the mass, the audience.” Bob Hope was different. When he went to do shows in a new town or college or military base, he would send advance men to scout the local scene—gathering information about the popular hangouts, names of local celebrities, and bits of local gossip. When he mentioned these in his monologue, the audience felt an instant bond. As an entertainer, he was the greatest grassroots politician of all time.

Hope got more fan mail than any other star of his day—thirty-eight thousand letters a week in 1944 by one estimate. That record may well have been broken in the age of rock idols and reality TV. But it’s hard to imagine any other entertainment personality—Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley or Justin Bieber—getting the volume of personal, heartfelt letters that Hope did. Servicemen thanking him for bringing a touch of home to a remote outpost during wartime. Parents of soldiers killed in action writing to thank Hope for providing a last glimpse of their son in the crowd at one of his Christmas shows. People who once met him or saw him onstage in vaudeville asking if he would stop by the house for dinner when he came through St. Louis. Old friends pouring out tales of woe and asking for loans or help in finding a job. Birthday greetings and get-well cards by the truckload. When he had eye problems that threatened his vision, dozens of people wrote to offer one of their own eyes so that Bob Hope could see. “I believe this operation can take place without newspapers or anyone finding out,” wrote one man, who said he had only months to live. “This will be my last gift to my fellow man.”

To read through Hope’s fan mail is to experience the sad drama of everyday human misfortune—illness, family problems, money troubles, disappointed dreams—and realize the beacon of inspiration, hope, and maybe even salvation that celebrities can represent. Hope must have understood this. He replied to an amazingly high proportion of his fan letters—with the help of a battery of assistants, to be sure, but with the kind of care and personal detail that only he could have supplied. Every letter from a serviceman who had seen him in World War II drew an attentive, individualized response—with a few jokes thrown in for good measure, something the letter writer could keep and cherish. A fan who sent a gift to Hope’s hotel room in Oklahoma City before a concert in 1974 got this charming response:

This is just to thank you for the lemon pie you sent to the hotel and to let you know I really enjoyed it. It gave me energy to fight off the cold I had and to go ahead and do the Stars and Stripes show. There are several ways to make a lemon pie and you have the proper format because it was just tart enough to be good, almost like my Mother used to bake, which is high praise.

For any other star the first sentence would have been enough, a pro forma thank-you that an assistant could easily have handled. But Hope himself had to add the details—his cold, the tartness—that doubtless earned him a fan for life, one of millions.

In 1967 Hope got this letter from the friend of a seven-year-old Wisconsin girl, whom he had met a year earlier when she was a poster child for cystic fibrosis. Now, the letter writer told him, the girl was dying:

She is in the hospital fighting for her life. The doctors give her about four months to live. She learned a few years ago that she was going to die, but the word “die” had no meaning to her. She recently began to understand what was going to happen. She is taking it hard, Mr. Hope, very hard. She falls apart at the word “die.” . . . It will help very much if you were to write a letter or note comforting her. I realize you are a very busy man and you don’t have time to answer every letter you get. But please, Mr. Hope. It might help so much.

Hope wrote this to the girl in response:

Dear Kelly:

Remember me? I had my picture taken with you last year in West Allis. I just heard that you were in the hospital and so I wanted to send you a little letter to tell you I’m hoping that you’re coming along all right and that you’re putting on a good fight so you can get out of there very soon.

I was in Madison, Wisconsin, the other night for a big show at the new auditorium. I did enjoy it and certainly wish I’d had a chance to see you. Anyway, I just wanted to let you know I’m thinking about you, hoping you will get a lot better and get out and enjoy the beautiful Wisconsin country.

A lot of people are praying for you. I am, too.

My best regards,

Bob Hope

It would take a hard-hearted celebrity to ignore a request like that, and an oafish one not to write a sensitive reply. But the delicacy of Hope’s response, its warmth and self-deprecating good humor (“Remember me?”), is a small work of art. Hope may have been a cold and driven man, a glutton for applause with an outsize ego. But he could also write a letter like that. In an era when stars routinely lament the tribulations of fame, complain about the loss of privacy, or lose their bearings to drugs and excess, Hope was one celebrity who loved being famous, appreciated its responsibilities, and handled it with extraordinary grace. His monumental role in our public life may have come at the expense of a private life that seemed, to many, stunted and incomplete. But for Hope, the sacrifice was worth it.

INTRODUCTION

On a balmy October morning in 2010, one hundred people were gathered on a dock in Battery Park at the foot of Manhattan Island. They were a well-dressed group—the men in jackets and ties, the women in business suits. Many were quite old and needed help climbing into the boat that had been chartered to ferry them across New York Harbor to Ellis Island. Once there, they made their way to the second floor of the cavernous Immigration Museum building, where rows of chairs had been set up in a long, book-lined room, which was about to be dedicated as the Bob Hope Memorial Library.

Linda Hope, the late comedian’s seventy-one-year-old daughter, stepped to the microphone to emcee the ceremony. She introduced the smattering of celebrities on hand—actress Arlene Dahl, baseball legend Yogi Berra, two US congressmen—and several clip reels highlighting Bob’s life and career: his childhood years in England, where he was born in 1903, and Cleveland, Ohio, where he and his family emigrated when he was four and a half; scenes from his movies and TV shows; excerpts from his tours to entertain US troops around the globe. His granddaughter, Miranda, accompanying herself on guitar, sang a folk ballad called “Immigrant Eyes.” Dick Cavett popped up from the audience to tell a couple of impromptu stories about Hope, whom he had befriended in the comedian’s later years. Michael Feinstein, the cabaret singer and musical archivist, closed the event with a wistful solo rendition of Bob’s theme song, “Thanks for the Memory.”

It was another chapter in what has surely been the most determined campaign of legacy building in Hollywood history. A few months before the Ellis Island ceremony, Hope’s family and friends gathered in Washington, DC, to inaugurate a new Hope-centric exhibit on political humor at the Library of Congress, where the comedian’s voluminous letters and papers are stored. A year earlier, the Hope legacy tour made a stop on the deck of the USS Midway in San Diego Harbor to mark the introduction of a postage stamp bearing Hope’s likeness. Memorials to Hope have proliferated across the American landscape. You can walk down streets named for Bob Hope in El Paso, Texas, Miami, Florida, and Branson, Missouri; cross the Cuyahoga River on the Hope Memorial Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio; and bypass the congestion at Los Angeles International by flying into the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, California. Hope’s name is memorialized on hospitals, theaters, chapels, schools, performing arts centers, and American Legion posts from Miami to Okinawa. The US Air Force named a transport plane for him, and the Navy christened a cargo ship in his honor. Bob Hope Village, in Shalimar, Florida, provides a home for retired members of the Air Force and their surviving spouses. The World Golf Hall of Fame, in St. Augustine, Florida, features an exhibit celebrating Hope’s passion for the game, “Bob Hope: Shanks for the Memory.” A dozen colleges offer scholarships in Hope’s name. Another dozen organizations give out awards in his honor, among them the Air Force’s annual Spirit of Hope Award and the Bob Hope Humanitarian Award, presented by the Academy of Television Arts & Science.

His punchy, two-syllable name, so emblematic of the optimistic American spirit; the unmistakable profile, with its jutting chin and famously ski-slope-shaped nose; the indelible images of Hope performing for throngs of cheering GIs in World War II and Vietnam—it was once impossible to imagine a time when the first question that needed to be answered about the most popular comedian in American history would be: Who was Bob Hope, and why did he matter?

By the time he died—on July 27, 2003, two months after his hundredth birthday—Hope’s reputation was already fading, tarnished, or being actively disparaged. He had, unfortunately, stuck around too long. The comedian of the century, who began his vaudeville career in the 1920s and was still headlining TV specials in the 1990s, continued performing well into his dotage, and a younger generation knew him mainly as a cue-card-reading antique, cracking dated jokes about buxom beauty queens and Gerald Ford’s golf game. “World’s Last Bob Hope Fan Dies of Old Age,” the Onion’s fake headline announced a year before his death. Writer Christopher Hitchens expressed the disaffection of many of the baby-boom generation in an online dismissal of Hope just a few days after his passing: “To be paralyzingly, painfully, hopelessly unfunny is a serious drawback, even lapse, in a comedian. And the late Bob Hope devoted a fantastically successful and well-remunerated lifetime to showing that a truly unfunny man can make it as a comic. There is a laugh here, but it is on us.”

Hope never recovered from the Vietnam years, when his hawkish defense of the war, close ties to President Nixon (who actively courted Hope’s help in selling his Vietnam policies to the American people), and the country-club smugness of his gibes about antiwar protesters and long-haired hippies, all made him a political pariah for the peace-and-love generation. His tours to entertain US troops during World War II had made him a national hero. By the turbulent 1960s, he was a court-approved jester, the Establishment’s comedian—hardly a badge of honor in an era when hipper, more subversive comics, from Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce to George Carlin and Richard Pryor, were showing that stand-up comedy could be a vehicle for personal expression, social criticism, and political protest. Even before Hope became a doddering relic, he had become an anachronism.

Yet the scope of Hope’s achievement, viewed from the distance of a few years, is almost unimaginable. By nearly any measure, he was the most popular entertainer of the twentieth century, the only one who achieved success—often No. 1–rated success—in every major genre of mass entertainment in the modern era: vaudeville, Broadway, movies, radio, television, popular song, and live concerts. He virtually invented stand-up comedy in the form we know it today. His face, voice, and stage mannerisms (the nose, the lopsided smile, the confident, sashaying walk, and the ever-present golf club) made him more recognizable to more people than any other entertainer since Charlie Chaplin. A tireless stage performer who traveled the country and the world for more than half a century doing live shows for audiences in the thousands, he may well have been seen in person by more people than any other human being in history.

His achievements as an entertainer, however, only hint at the breadth and depth of his impact. For the way he marketed himself, managed his celebrity, cultivated his brand, and converted his show-business fame into a larger, more consequential role for himself on the public stage, Bob Hope was the most important entertainer of the century. Viewed from the largest historical perspective—the way he intersects with the grand themes of the century, from the Greatest Generation’s crusade to preserve democracy in World War II, to the social, political, and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s—one could argue, without too much exaggeration, that he was the only important entertainer.

His life almost perfectly spanned the century, and to recount his career is to recapitulate the history of modern American show business. He began in vaudeville, first as a song-and-dance man and then as an emcee and comedian, working his way up from the amateur shows of his Cleveland hometown to headlining at New York’s legendary Palace Theatre. He segued to Broadway, where he costarred in some of the era’s classic musicals, appeared with legends such as Fanny Brice and Ethel Merman, and introduced standards by great American composers such as Jerome Kern and Cole Porter. Hope became a national star on radio, hosting a weekly comedy show on NBC that was America’s No. 1–rated radio program for much of the early 1940s and remained in the top five for more than a decade.

He came relatively late to Hollywood, making his feature-film debut, at age thirty-four, in The Big Broadcast of 1938, where he sang “Thanks for the Memory”—which became his universally identifiable, infinitely adaptable theme song and the first of many pop standards that, almost as a sideline, he introduced in movies. With an almost nonstop string of box-office hits such as The Cat and the Canary, Caught in the Draft, Monsieur Beaucaire, The Paleface, and the popular Road pictures with Bing Crosby, Hope ranked among Hollywood’s top ten box-office stars for a decade, reaching the No. 1 spot in 1949.

Hope brought a new kind of character and attitude to the movies. He was the brash but self-mocking wise guy, a braggart who turned chicken in the face of danger, a skirt chaser who quivered like Jell-O when the skirt chased back. “I grew up loving him, emulating him, and borrowing from him,” said Woody Allen, one of the few comics to acknowledge how much he was influenced by Hope—though nearly everyone was. Hope played variations on his cowardly character in spy comedies, ghost stories, costume epics, Westerns—but always with a winking nod to the audience, an acknowledgment that he was an actor playing a role. Especially in his interplay with Crosby in the Road films, Hope often spoke directly to the camera or stepped out of character to make cracks about the studio, his career, and his Hollywood friends. This improvisational, fourth-wall-breaking spirit was a radical break from the stylized sophistication of the 1930s romantic comedies, or the artifice of other vaudeville comics who transitioned into movies, such as W. C. Fields or the Marx Brothers. And it perfectly met the psychological needs of a nation at a time of war and world crisis. As the newsreels broadcast scenes of thundering European dictators, jackbooted military troops, and docile, mindlessly cheering crowds, Hope’s humor was both an escape and an affirmation of the American spirit: feisty, independent, indomitable.

When television came in, Hope was there too. Others, such as Milton Berle, preceded him. But after starring in his first NBC special on Easter Sunday in 1950, Hope began an unparalleled reign as NBC’s most popular comedy star that lasted for nearly four decades. Other comedians who made the move into television—Berle, Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Jackie Gleason, Danny Thomas, even Lucille Ball—had their heyday on TV and then faded; Hope alone remained a major star headlining top-rated TV shows well into his eighties. His 1970 Christmas special from Vietnam was the most watched television program of all time up to that point, seen in a now-unthinkable 46.6 percent of all TV homes in the country. (The final episodes of Dallas, M*A*S*H, and Roots are the only entertainment shows ever to beat it.)

That would have been enough for most performers, but not Hope. Along with his radio, TV, and movie work, he traveled for personal appearances at a pace matched by no other major star. He was just one of many performers who went overseas on USO-sponsored tours to entertain the troops during World War II. Unlike most of the others, he didn’t stop when the war ended. Starting with a trip to Berlin during a Cold War crisis in 1948, he launched an annual tradition of entertaining US troops around the world at Christmas—in wartime and peacetime, from forlorn outposts in Alaska to the battlefields of Korea and Vietnam. Stateside, he was just as indefatigable, making as many as 250 personal appearances a year, manning the microphone at charity benefits, trade shows, state fairs, testimonial dinners, hospital dedications, Boy Scout jamborees, Kiwanis Club luncheons, and seemingly any event that could pack a thousand people into a ballroom on the promise that Bob Hope would be there to deliver the one-liners.

On a podium, no one could touch him. He was host or cohost of the Academy Awards ceremony a record nineteen times—the first in 1940, when Gone With the Wind was the big winner, and the last in 1978, when Star Wars and Annie Hall were the hot films. His suave unflappability—no one ever looked better in a tuxedo—and tart insider wisecracks (“This is the night when war and politics are forgotten, and we find out who we really hate”) helped turn a relatively low-key industry dinner into the most obsessively tracked and massively watched event of the Hollywood year.

The modern stand-up comedy monologue was essentially his creation. There were comedians in vaudeville before Hope, but they mostly worked in pairs or did prepackaged, jokebook gags that played on ethnic stereotypes and other familiar comedy tropes. Hope, working as an emcee and ad-libbing jokes about the acts he introduced, developed a more freewheeling and spontaneous monologue style, which he later honed and perfected in radio. To keep his material fresh, he hired a team of writers and told them to come up with jokes about the news of the day—presidential politics, Hollywood gossip, California weather, as well as his own life, work, travels, golf game, and show-business friends.

This was something of a revolution. When Hope made his debut on NBC in 1938, the popular comedians on radio all inhabited self-contained worlds, playing largely invented comic characters: Jack Benny’s effete tightwad, Edgar Bergen and his uppity dummy, Charlie McCarthy, the daffy-wife/exasperated-husband interplay of George Burns and Gracie Allen. Hope’s monologues brought something new to radio: a connection between the comedian and the outside world.

Hope was not the first comedian to do jokes about current events. Will Rogers, the Oklahoma-born humorist who offered folksy and often pointed commentary on politics and the American scene, achieved huge popularity in vaudeville, movies, and radio in the 1920s and 1930s, before his death in a plane crash in 1935. Fred Allen, the frog-voiced radio satirist, was aiming acerbic and literate barbs at the potentates of both Washington and his own network while Hope was still apprenticing. But Hope was the first to combine topical subject matter with the rapid-fire gag rhythms of the vaudeville quipster. His monologues became the template for Johnny Carson and nearly every late-night TV host who followed him, and the foundation stone for all stand-up comics, even those who rebelled against him.

Hope wasn’t a political satirist. His jokes never hit hard, cut deep, or betrayed any political viewpoint. Mostly they took personalities and events from the news and lampooned them for superficial things, or with clever wordplay—an ironic juxtaposition or unexpected twist or jokey hyperbole. “Not much has been happening back home,” Hope told a crowd of servicemen after the 1960 presidential election. “Hawaii and Alaska joined the union, and the Republicans left it.” He poked fun at new California governor Ronald Reagan for his Hollywood pedigree, not his conservative politics: “California’s back to a two-party system: the Democrats and the Screen Actors Guild.” When Bobby Kennedy was thinking of running for president, Hope joked about the candidate’s growing brood of kids: “He may win the next election without leaving the house.” On hot-button issues such as gay rights, Hope’s gags amiably skirted any potential land mines: “In California homosexuality is legal. I’m getting out before they make it mandatory.”

He was the first comedian to openly acknowledge that he used writers—as many as a dozen at a time, turning out hundreds of potential jokes for each monologue. He saved them all, the keepers and the castoffs, in a fireproof vault in the office wing of his home in Toluca Lake, California—more than a million of them by the end of his career, all filed alphabetically according to subject matter (“Fairs, Fans, Finance, Firemen, Fishing . . .”). The jokes were rarely memorable, trenchant, or even very funny, and his dependence on writers would later be scorned by younger comedians, who mostly wrote their own material. Yet the jokes were always the weakest part of his act; his impeccable delivery is what put them across. The lamest formula gags could get laughs through the sheer force of his style and stage presence: the confident manner, the rat-a-tat pace and clarion tone of his voice, the perfect weight and balance given to each word, the way he barreled through a punch line and began the next setup (“But I wanna tell ya . . .”) until the laughter caught up with him—a technique that both bullied the audience into laughing and congratulated it for keeping up.

This was more than just the triumph of style over substance. Like the great pop and jazz singers of the pre-rock era, who performed songs written by others (before the Beatles came along, and singers had to become songwriters too), Hope was not a creator but a great interpreter. He didn’t necessarily say funny things, but he said them funny. Larry Gelbart, who wrote for Hope on radio for four years, before creating the hit TV series M*A*S*H, recalled watching Hope onstage at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre in 1948 and being surprised at the belly laughs he got for a joke whose punch line mentioned a motel.

“Do you think anybody here knows what the word motel means?” Gelbart asked the pretty British girl he was with.

“No,” she replied.

“Then why were you laughing?”

“Because he’s so funny.”

Hope sold an attitude: brash, irreverent, upbeat. He was a product of Middle America—“the unabashed show-off, the card, the snappy guy who gets off hot ones at shoe salesmen’s conventions while they’re waiting for the girls to show up,” as humorist Leo Rosten once put it—who eased the country’s anxieties through complex and difficult times. The message of his comedy was that no issue was so troubling, no public figure so imposing, no foreign threat so intimidating, that it couldn’t be cut down to size by some good old American razzing. Hope’s comedy punctured pomposity and fed a healthy skepticism of politics and public figures. It helped Americans process changing mores, from new roles for women during World War II to the counterculture revolution of the 1960s. If the jokes were sometimes corny, even reactionary, Hope could be excused. He transcended comedy; he was the nation’s designated mood-lifter. No one else could perform that role; few even tried. Comedians for years did impressions of Jack Benny, Groucho Marx, George Burns, and other classic clowns. Almost no one did Bob Hope. His ordinariness was inimitable.

• • •

The machinelike impersonality of Hope’s comedy mirrored the impenetrability of Hope the man. Even to intimates and people who worked with him for years, he remained largely a cipher. He was not given to introspection or burdened with inner angst. He was the last person in Hollywood one could imagine walking into a therapist’s office. He never read books or went to art museums, unless he was dedicating the building. “Bob had no intellectual curiosity,” said a younger writer who befriended him in his later years. “If it didn’t concern him, he didn’t care.” He had just one hobby, golf—which provided him with access to presidents, corporate titans, and other power brokers, as well as the material for endless jokes. He authored several memoirs, but all were ghostwritten and filled with one-liners rather than revelations about his inner life.

In public he could be charming, charismatic, and surprisingly approachable. Always attentive to fans, he rarely turned down an autograph request or failed to acknowledge a compliment. He had a photographic memory for names and faces—people he had met at fund-raising events or on the golf course, even the officers of army units he had once entertained. In social gatherings, the room would galvanize around him. “Everybody came to attention when he walked into the room or when they were engaged in conversation with him,” said Sam McCullagh, his former son-in-law. “He had a bright spirit—the way you say a saxophonist has a bright sound. The room lit up. His personality beckoned you.”

He was funny even without his writers. Unlike some comedians, driven by insecurity and a need for constant attention, Hope was not always “on,” rattling off one-liners in normal conversation. Yet he had a natural, unforced, possibly brilliant wit. His writers could see it in the material they didn’t write for him. “He was funnier than the monologues,” said Larry Gelbart. “He was original. He would rather die than call you by your real name—he called me Fringe because I used to have a very short haircut. He spoke the way Johnny Mercer wrote lyrics, always colorful, with a twist.”

His TV and radio audiences could glimpse it in the ad-libs that popped so easily from him when slipups occurred on the air—the wisecrack after a fumbled line or missed cue, which made those now-clichéd “blooper reels” funnier than the sketches they supposedly ruined. Friends and colleagues saw it in his ability to respond in the moment, in ways no script could predict. A Times of London reader, in a letter to the editor a few days after Hope’s death, recalled sitting behind Hope on a shuttle flight between New York and Boston in the 1960s, when hijackings to Cuba were in the news. Though it was an utterly routine one-hour flight, a starstruck stewardess fawned over her celebrity passenger. “Mr. Hope,” she cooed, “I hope you will save your ticket and boarding pass, because I mean to make this one of your most memorable airline flights ever.” Hope’s dry response: “My God, not Havana again.” A family member marveled at Hope’s opening line at a luncheon for the Catholic diocese of St. Louis in the early 1970s. The bishop who was to introduce Hope launched unexpectedly into a long comedy routine of his own, cracking up the room. Finally the prelate wrapped up his monologue and introduced the comedian who was the guest of honor. Hope walked to the microphone and began soberly, “Let us pray.”

Yet his personality had an essential coldness, a wall that prevented outsiders from getting behind the flip, impenetrable surface. For the writers who worked for him, he was an affable, good-humored boss, one of the boys. But the narcissism could be oppressive. He expected them to be on call at any hour of the day or night; he was known for his late-night phone calls, to suggest a new topic for jokes he needed by morning or simply to repeat a funny story he had just heard (often a dirty one). “Once you worked for Hope, you were his property, and just on loan to the rest of the world,” said Hal Kanter, who wrote for him off and on for forty years. He was notoriously tight with a dollar, a boss who could complain about reimbursing employees for the cost of a cab ride. Yet he was generous with relatives and friends who were down on their luck, many of whom he quietly helped out financially for years.

He surrounded himself with a battalion of lawyers, agents, public relations men, and assistants of various kinds, who helped manage his public image and protected him from the rough edges of everyday life. Once he called up a neighborhood movie theater and asked what time the feature started. The theater manager replied, “What time can you get here?” He never wore a watch—others could tell Bob Hope the time. He never apologized and rarely said thank you. His longtime publicist Frank Liberman recalled Hope’s unhappiness at the lack of press coverage for a special he was set to host at Madison Square Garden in the 1960s. Finally Liberman landed Hope a coveted interview with the New York Times. The star’s only response: “Now you’re talkin’.”

For journalists, he was a frustrating interview, glib and stubbornly unrevealing. J. Anthony Lukas, who wrote a profile of Hope for the New York Times Magazine in 1970, at the height of the embattled Vietnam years, recounted a telling anecdote from one of Hope’s publicists. A magazine reporter, interviewing Hope on an airplane, grew increasingly frustrated with his flip responses to her questions about what motivated him as a performer. When she got up to go to the bathroom, the publicist took Hope aside and told him, “Bob, this gal comes from New York, where they’re very big on psychoanalysis. The only way to stop her is to tell her you work so hard because you’re the fifth of seven sons and you had to compete for your mother’s attention.” When the reporter returned, Hope repeated the publicist’s answer almost word for word. The reporter smiled happily, and her story wound up quoting his revelation—made “in a rare moment of introspective analysis.”

It’s not just that Hope was closed off. He seemed to regard the details of his biography and private life as fungible particulars, to be shaped and rewritten as needed for public consumption. He had one of the longest-running and most celebrated marriages in Hollywood—for sixty-nine years, to former nightclub singer Dolores Reade. But he was a lifelong womanizer, carrying on a string of extramarital affairs that were an open secret to friends and colleagues, but largely kept under wraps by his entourage and the press. He had a secret, short-lived first marriage, to his former vaudeville partner, which he never publicly acknowledged. And he almost certainly fudged the date and place of his marriage to Dolores—which, since there is no record of it, some family members suspected may never have taken place at all.

Yet it was, in its fashion, a good marriage. Bob depended on Dolores, a smart, strong-willed Catholic, for counsel, support, and the proper image of Hollywood domesticity. She ran the household, raised their four adopted children, and organized his social life. Hope was a playful, not uncaring, but distant and frequently absent father—a fleeting presence at family dinners, who would typically arrive late and dash off early, always running to appointments. His children had fond memories of their limited time with him, but also varying degrees of trouble coping with the burden of having Bob Hope as a father. It may have weighed most heavily on his youngest daughter, Nora, who broke with the family entirely after a dispute with her mother in the 1980s and remained estranged for the rest of her parents’ lives.

If any of this caused Hope serious angst, he kept it well hidden. A Los Angeles Times profile in 1941 called him “the world’s only happy comedian,” and it may not have been far from the truth. He was energized by performing, never seemed stressed, and kept up an exhausting work schedule well into his eighties. He refreshed himself with frequent catnaps, daily massages, and long walks every night before he went to bed, no matter how late the hour or unfamiliar the terrain (usually with a companion—and in later years a golf club for protection). Though one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood, he had a relatively unpretentious lifestyle, raising his family not in the ritzy enclaves of Beverly Hills or Bel Air, but in the San Fernando Valley bedroom community of Toluca Lake. He had a second home in the desert resort of Palm Springs, but it was a relatively modest three-bedroom retreat until the 1970s, when Dolores oversaw the construction of a giant, modernist showplace, with a dome-shaped roof that reminded many of the TWA terminal at New York’s JFK Airport.

He was on a first-name basis with presidents and generals, corporate leaders, and business titans. But his closest friends were the people he worked with—writers, old cronies from Cleveland, former vaudevillians, businessmen who joined him for golf and supplied him with clothes and other freebies. Until his later years he drove his own car—not a fancy Mercedes, but one of the middle-class Chryslers or Buicks given to him by his TV sponsors. Despite a busier travel schedule than practically any other star in Hollywood, he didn’t have a private plane until late in life, when his friend and San Diego Chargers owner Alex Spanos loaned him one. After seeing how much it cost to maintain, Hope gave it back.

To many he seemed hopelessly shallow: a gleaming perpetual-motion machine with a missing piece at the center. “Deep down inside, there is no Bob Hope,” writer Martin Ragaway once said. “He’s been playing Bob Hope for so long that everything else has been burned out of him. The man has become his image.” But what seemed shallowness was merely a sign of how effectively Hope was able to guard his private life, and the almost superhuman intensity of focus on his public one. His manager, Elliott Kozak, liked to say that every morning Bob Hope would get up, look in the mirror, and say to himself, “What can I do today to further my career?” That relentless dedication to his own stardom allowed Hope to virtually redefine the notion of stardom in the twentieth century. Indeed, there is hardly an element of our modern celebrity culture that Bob Hope did not invent, pioneer, or help to popularize. He was largely responsible, in the age of celebrity, for setting the parameters of what it means to be a celebrity:

THE STAR AS BUSINESSMAN. Like nearly every movie star of the 1930s and 1940s, Hope was initially a salaried employee, signing regular contracts with his studio, Paramount Pictures, for a specified number of films per year at a fixed fee. But in the mid-1940s, when he was churning out box-office hits like clockwork, Hope set up his own production company, so that he could have an ownership stake in his movies and keep more of the profits. A few years later he made a similar deal with NBC, becoming the producer of his own TV specials and charging the network a license fee for them—enabling him to own his shows in perpetuity. Hope wasn’t the first Hollywood star to become an entrepreneur of his own career; he patterned his Paramount deal after one that his friend Bing Crosby had made with the same studio a few years earlier. But his business arrangements were the most successful and highly publicized of his day, and a model for the production companies and packaging deals that have become routine for nearly every major star in Hollywood.

Hope’s business acumen became part of his legend. By the late 1940s he was making more than $1 million a year, when that was real money. He invested it shrewdly, first in oil and then in California real estate, buying up huge parcels of land in the San Fernando Valley and elsewhere; at one time he was reputed to be the largest private landowner in the state of California. Fortune magazine in 1968 estimated his net worth at over $150 million—making him the richest person in Hollywood, wealthier even than studio moguls. He was forever complaining that such estimates were too high, and he may have been right. After Forbes magazine put him on its list of America’s four hundred richest people in 1982, he challenged the magazine to prove it and got his net worth downgraded from over $200 million to a measly $115 million. Still, Hope was rich, a canny businessman, and a key figure in the gradual shift of power in Hollywood away from the studio and network moguls and toward the stars who kept them in business, and who began taking control of their own financial destiny.

THE STAR AS BRAND. Hope was voracious in seeking out new audiences, marketing his fame across what would today be called multiple platforms. He had been a movie and a radio star for only three years when he published his first book—a jokey, illustrated memoir (penned largely by his gag writers) called They Got Me Covered. It was a surprise bestseller, and Hope went on to author or coauthor eleven more books, including another, more substantial autobiography, memoirs of his travels during World War II and Vietnam, and books about golf and his encounters with presidents. He promoted all of them tirelessly, in personal appearances around the country, on his own TV specials, and in guest spots on other TV shows—an early demonstration of the power of show-business synergy.

He was Hollywood’s inventor of the brand extension. Along with the books, he had a daily syndicated newspaper column (ghosted, as always, by his writers), which began with dispatches from his World War II tours and continued for eight years afterward, into the early 1950s. He brought his name, prestige, and showbiz connections to a struggling Palm Springs golf tournament, renamed it the Bob Hope Desert Classic, and turned it into the most star-studded pro-am event on the PGA Tour. He was the star of a comic book: The Adventures of Bob Hope, launched in 1950 by DC Comics and published quarterly for the next eighteen years. He even had his own logo—the familiar line-drawn caricature of his concave-shape profile, instantly recognizable from Boston to Bangkok.

THE STAR AS PUBLIC CITIZEN. Hope was far from the only Hollywood star who used his talents to raise money for charitable causes. But no one else pursued his public-service mission so fervently or made it such an integral part of his image. He was awarded the first of five honorary Oscars in 1941, for being “the man who did the most for charity.” He was the most celebrated of the stars who toured the Pacific and European theaters to entertain the troops during World War II. Back home after the war, he became a ubiquitous fund-raiser, host of charity events, and supporter of patriotic causes, securing his reputation as Hollywood’s most tireless do-gooder.

All this had a careerist aspect, of course. Hope sincerely loved entertaining the troops, and it fed the patriotic pride of an immigrant who had lived a classic Horatio Alger success story. But his troop shows also provided him with huge, easy-to-please audiences, lofty TV ratings, and boundless good publicity. Still, no cynical view of his motives can diminish the impact that Hope had in setting a standard for public service in Hollywood. “Playing the European theater, or any theater of war, is a good thing for actors,” he wrote in I Never Left Home, the memoir of his World War II travels. “It’s a way of showing us that there’s something more important than billing; or how high your radio [rating] is; or breaking the house record in Denver.” Hope showed by example that Hollywood stars have an opportunity, even an obligation, to do more than just make movies, sign autographs, and buy oceanfront estates in Malibu. They can give back, do good, use their fame to make an impact in the public arena.

Hope’s particular causes and conservative political views, of course, were not the same as those of many of the stars who followed his example. But he opened the way for celebrities to have causes and political views—to work for endangered whales or starving children in Africa or hurricane victims in Louisiana. They may not acknowledge or even realize it, but a direct generational line connects Bob Hope to the globe-trotting activism of Angelina Jolie and George Clooney, Madonna and Oprah Winfrey. Hope made it safe for celebrities to be taken seriously as public citizens.