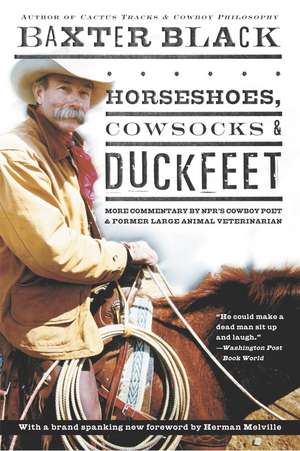

Horseshoes, Cowsocks & Duckfeet: More Commentary by NPR's Cowboy Poet & Former Large Animal Veterinarian

Autor Baxter Blacken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2003

Drawn in part from Baxter’s wildly popular NPR commentaries and syndicated columns, Horseshoes, Cowsocks & Duckfeet offers a generous helping of his tender yet irreverent, sage-as-sagebrush take on everything from ranching, roping, Wrangler jeans, and rodeos to weddings and romance, the love of a good dog, dancing, parenting, cooking up trouble, and talking about the weather. If you haven’t ridden with Baxter before, find out what more than a million dedicated fans are laughing about inside and outside the corral.

Preț: 109.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 164

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.98€ • 21.82$ • 17.32£

20.98€ • 21.82$ • 17.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400049431

ISBN-10: 1400049431

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 16 PIECES LINE ART

Dimensiuni: 156 x 235 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400049431

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 16 PIECES LINE ART

Dimensiuni: 156 x 235 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

BAXTER BLACK is an NPR commentator whose syndicated column appears in more than 100 newspapers. He appears regularly on television and radio and at dozens of agricultural functions and the occasional urban gathering. He will not let himself be described as America’s best-loved cowboy poet, but will agree to be referred to as the tallest, scrawniest, most left-handed one. He lives in Arizona among the catclaw and Gila monsters.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Several years ago I had a job in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It coincided with my first big loss in the stock market. Thank goodness it was still less than my accumulated cattlefeeding losses or the first divorce. I drove west on I-10 to Acadiana to see if Cajuns were real. I got as far north as Fred's in Mamou and as far south as Cypremort Point on the gulf. I reveled in the culture, wallowed in its strangeness, and was swallowed up by the natives. I forgot Wall Street.

I have returned often. It is one of the few foreign countries I enjoy visiting.

CAJUN DANCE

"Deez gurls ken dance."

He was right. I was flat in the middle of a magic place . . . Whiskey River Landing on the levee of the Atchafalaya Swamp in "sout' Looziana."

The floor was givin' underneath the dancers. The Huval family band was drivin' Cajun music into every crevice and cranny, every pore and fiber, every pop, tinkle, and nail hole till the room itself seemed to expand under the pressure.

The slippers glided, stomped, kicked, and clacked. They stood on their toes, rocked on their heels, they moved like water skippers on the top of a chocolate swamp. Pausing, sliding, setting, pirouetting, leaping from a starting block, braking to a smooth stop, heaving to boatlike against a floating pier.

Then off again into the blur of circling bare legs, boot tops, and bon temps all in perfect rhythm to the beating of the bayou heart.

I have lived a fairly long time. I have been places. I have seen bears mate, boats sink, and gila monsters scurry. I have danced till I couldn't stand up and stood up till I couldn't dance. I've eaten bugs, broccoli, and things that crawl on the seafloor. I have seen as far back as Mayan temples, as far away as Betelgeuse, and as deep down as Tom Robbins. I have been on Johnny Carson, the cover of USA Today, and fed the snakes at the Dixie Chicken.

I have held things in my hand that will be here a million years beyond my own existence.

Yet, on that dance floor, I felt a ripple in the universe, a time warp moment when the often unspectacular human race threw its head back and howled at the moon.

Thank you, Napoleon; thank you, Canadiens; and thank you, Shirley Cormier and the all-girl Cajun band. It was a crawfish crabmeat carousel, a seafood boudin Creole belle, an Acadian accordian, heavy water gumbo etouffee, Spanish moss jambalaya, and a Tabasco Popsicle where you suck the head and eat the tail.

My gosh, you can say it again: "Deez gurls ken dance."

It is difficult to find, except in academic circles, practicing veterinarians who have lost their humility. I think it is because of the company we keep. Animals are not respecters of good looks, intelligence, prestigious honors, or fashion sense.

They remind us regularly of our real place in the food chain.

A COLD CALL

Through rain or sleet or snow or hail, the vet's on call to . . . pull it or push it or stop it or start it or pump it or bump it, to hose it or nose it, to stay the course till wellness doth prevail.

It was a cold winter in southern Michigan: -3 degrees. Dr. Lynn the veterinarian got the call after supper from a good client. Their four horses had illegally gained entrance to the tack room and eaten 150 pounds of grain.

She drove out to the magnificently refurbished, snow-covered countryside horse farm of the couple, a pair of upscale twenty-something Internet millionaires. The three crunched their way back to the rustic, unimproved forty-year-old barn where the horses were now in various poses of drooling gastric distress.

A quick auscultation showed no intestinal movement and membranes the color of strawberry-grape Popsicle tongue. Lynn began her work under the one lightbulb. There was no door, but at -3 degrees, who cares. The Banamine was as thick as Miracle Whip, her stomach hose was as rigid as PVC pipe, and her hand stuck to the stainless steel pump. It was so cold her shadow cracked when she stepped on it.

She pumped her patients' stomachs with Epsom salts and mineral oil. One of the horses, however, did not respond. She instructed the couple to walk the horses while she went up to the house to call the surgeon at the vet school. (Even her cell phone had frozen and would only dial odd numbers.)

As she stepped through the back door of the main house, she remembered that the couple had a pair of Akitas named Whiskey and Bear. Surely the dogs aren't loose in the house, Lynn thought, or they would have said something. She dialed the phone on the kitchen wall. As it was ringing, she heard the click-click-click of toenails on the hardwood floor. Around the corner came a massive beast big as a Ford tractor. His sled dog ruff stood straight up on his neck. The curled tail never moved and the gaze was level. "Good dog, Whiskey, good dog . . . I'm just borrowing the phone here. . . ."

Dogs often remember their vet the way children remember their dentist. Whiskey sniffed Lynn's leg.

"Good dog . . . oh, yes, I'd like to speak to--YEOW!"

The au pair staying with the young millionaires heard a screaming clatter. She stepped around the door to be met by Whiskey dragging the good doctor down the hallway by a Carhartt leg, her arms flailing, trailing stethoscope, gloves, stocking cap, syringes, and steamed-up glasses like chum from a trawler. They were stopped when the phone cord came tight.

"Let the nice vet go, Whiskey," the au pair said in a Scandinavian accent. "She's only trying to help."

The difference between city and country can be as gray as a country-pop crossover hit or as black and white as five-buckle overshoes versus tasseled loafers. But when the twain shall meet, you can hear the rubbing of cultural tectonic plates.

AIN'T SEEN NUTHIN' YET

Mick owned a gas station alongside Interstate 80 in Hershey, Nebraska. It was to supplement his "agricultural habit," as he called his farming operation.

One hot afternoon, a sporty vehicle with Massachusetts plates pulled in to gas up. The driver unwound himself from the bucket seat, stood on the gravel, and stretched. He let his gaze travel the full circumference of the horizon around him.

"My gosh!" he said, somewhat overwhelmed, "what do you do out here in the middle of nowhere?"

"We jis' scratch around in the dirt and try to get by," answered Mick.

"This is the most desolate place I've ever been! There's nuthin' here!"

"Where ya goin'?" asked Mick.

"San Francisco."

"On I-80?"

"Yep."

"Well," said Mick, "you ain't seen nuthin' yet."

Where, exactly, is "nuthin'"? According to Mick, it waited for this pilgrim on down the road. It is 638 miles from Hershey to Salt Lake City, the next city with smog on I-80.

In contrast, I-95 runs 430 miles from Boston to Washington, D.C. In between, it passes through Providence, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, all of which are bigger than Salt Lake City.

But after this poor traveler got his transfusion in Salt Lake, nuthin' waited for him farther down the road. Picture 525 miles on I-80 west to Reno with nuthin' but Nevada in between.

Some folks say you might see nuthin' on I-10 from Junction to El Paso, or nuthin' on Hwy. 200 from Great Falls to Glendive, or nuthin' on I-40 on from Flagstaff to Barstow, or Hwy. 20 from Boise to Bend, or nuthin' on Hwy. 43 from Edmonton to Grande Prairie.

In my ramblings, I've seen a lot of nuthin'. It appeals to me; breathin' room, big sky. Matter of fact I've seen nuthin' in busy places like south New Jersey, the Appalachian Trail, the Ozarks, the U.P., or outside Gallipolis. You gotta look a little harder, but it's there. Nuthin', that is.

Mick sold the gas station, but he still lives in Hershey. He says it feels like home.

Feels that way to me, too. There's somethin' about nuthin' I like.

Cowboy stories are strewn with wrecks. Horse wrecks, cow wrecks, financial wrecks, Rex Allen, and Tyrannoeohippus Rex. And although one could make them up, it's not necessary. They are a daily occurrence.

WHEN NATURE CALLS

Russell asked me if I'd ever heard of a flyin' mule. "You mean parachuting Democrats?" I asked.

He and a neighbor had hired a couple of day work cowboys to help round up cows on the Black Range in southeastern Arizona. Billy, one of the cowboys, brought a young mule to "tune up" durin' the weeklong gather. When they had ridden the saddled mule through the Willcox auction ring, he'd looked pretty good. But afterward when Billy went to load him, he got his first inkling that all was not as it appeared.

The sale barn guys had the mule stretched out and lyin' down between a post and a heel rope. "To take the saddle off," they explained. "He's fine once yer mounted, but you can't get near him when yer on the ground!"

First morning of the roundup, Billy managed to get Jughead saddled. He had to rope him and tie a foot up to get it done. Then they all sat around for two hours drinkin' coffee till sunup.

As they left the headquarters at daylight, Billy made arrangements to meet Russell at a visible landmark. With all that coffee he'd been drinkin', he knew a "call of nature" was imminent and he'd need help gettin' back on Jughead.

Billy gathered a handful of critters but missed the landmark. By then his kidneys were floating.

The country was rough and brushy. He spotted a ten-foot scraggly pine on the edge of a four-foot embankment. It gave Billy an idea. Not a good idea, but remember, he was desperate and he was a cowboy.

He dropped his lasso around the saddle horn and rode up next to the tree. He passed the rope around the trunk and dallied onto the horn. The plan was to snug Jughead up close, get off, do his business, then remount.

The plan went awry.

Jughead started buckin' around the tree on the long tether. He made two passes before Billy lost his dally. Brush and cactus, pine boughs, and colorful epithets filled the air! With each ever-tightening circle, the rope climbed higher up the trunk. The higher they climbed, the more time they spent airborne.

Jughead was hoppin' like a kangaroo when the treetop bent and the uppermost coils peeled off. Mule and cowboy were midair when they hit the end of the line. Jughead went down and Billy spilled into the arroyo.

Almost on cue, Russell came crashin' up outta the creek bottom, "Mount up, Billy. We need help!"

Billy's hat was down around his ears, and he looked like he'd bitten off the end of his nose.

"Uh, go ahead and shake the dew off your lily," said Russell generously. "I guess we've got time."

Billy labored to one knee. "Never mind," he said, "I went in flight."

Some commentators just can't leave well enough alone.

ONLY EWES CAN PREVENT WILDFIRE

We have long known the sheep to be a two-purpose animal: meat and wool. Now the Nevada Extension Service is finding another purpose: fire control.

Practicing a technique successfully used in California and British Columbia, the Nevadans are using high-density, short-duration grazing to mow the fire-prone grass and sagebrush.

Their motto is "Only ewes can prevent wildfire."

When I first heard about using sheep in fire control, I had a moment's difficulty picturing the scene. Were they flying in low and dropping woolly beasts on hot spots? Were they fitting lambs with gas masks and shovels, then parachuting them into the forest? Or were sheep serving some useful function at the base camp? Waiting tables, perhaps nursing wounds, or simply offering comfort to the firefighters in the form of a shoulder or fleece to lean on?

No! Of course not. The sheep simply eats everything in sight so that nothing is left to burn.

Pretty clever, these Extension Service people. I understand they might apply for a grant to examine other alternative uses for sheep. I've come up with some possibilities they might test.

Need a replacement for the waterbed? Sleep on a bed of sheep. When trail riding or camping, just bring three or four head along. They can reduce fire danger and you can count them at night.

How about soundproofing? When a teenager pulls up beside you in traffic and his hi-fi-whale communicating car stereo is so loud it makes seismic waves in your 7-Eleven Styrofoam cup, you can immediately dial 922-BRING-A-EWE. An emergency crew will be dispatched to the scene and will stuff sheep inside the teen's car until the sound is properly muffled.

Or how 'bout a safety device in automobiles to replace the airbag? In the event of a crash, a Bag o' Sheep explodes from the dash, absorbing the impact, then escapes out the broken windows.

In a hurry at the airport, but don't have time for a shine? Try the Basque Sheep Buffer. Two strong people from Boise drag a ewe over your boot toes, side to side. They glisten with lanolin, and in a hot dance hall when the grease starts steaming, no tellin' what can happen.

Other things come to mind: sheep as large drain stoppers, self-propelled sponges, or a place to store your extra Velcro.

But the alternative use for sheep that may have the greatest potential: Q-tips for elephants.

There are fourteen definitions derived from this story explained in the glossary of this book.

COWBOY VOCABULARY MISCONCEPTIONS

This piece has an agricultural-cowboy slant. However, I am aware that urban people (Gentiles, I call them) read it as well. So when I lapse into my "cowboy vocabulary," I appreciate that some of my meanings could be unclear. Listed are some common misconceptions:

Statement: "My whole flock has keds."

Misinterpretation: Sheep are now endorsing tennis shoes.

Statement: "I'm looking to buy some replacement heifers, but I want only polled cattle."

Misinterpretation: His cows are being interviewed by George Gallup.

Statement: "I'm going to a gaited horse show."

Misinterpretation: A horse performance being held in an exclusive residential area.

Statement: "I work in a hog confinement facility."

Misinterpretation: She teaches classes in the campus jail at University of Arkansas.

Statement: "I prefer the Tarentaise over the Piedmontese."

Misinterpretation: He is picky about cheese.

Statement: "They've had a lot of blowouts at the turkey farm this year."

Misinterpretation: Sounds like they better change tire dealers.

Statement: "This mule is just a little owly."

Misinterpretation: His ears stick up? He's wise beyond his species limitation? No, wait, he looks like Benjamin Franklin or Wilford Brimley?

From the Hardcover edition.

I have returned often. It is one of the few foreign countries I enjoy visiting.

CAJUN DANCE

"Deez gurls ken dance."

He was right. I was flat in the middle of a magic place . . . Whiskey River Landing on the levee of the Atchafalaya Swamp in "sout' Looziana."

The floor was givin' underneath the dancers. The Huval family band was drivin' Cajun music into every crevice and cranny, every pore and fiber, every pop, tinkle, and nail hole till the room itself seemed to expand under the pressure.

The slippers glided, stomped, kicked, and clacked. They stood on their toes, rocked on their heels, they moved like water skippers on the top of a chocolate swamp. Pausing, sliding, setting, pirouetting, leaping from a starting block, braking to a smooth stop, heaving to boatlike against a floating pier.

Then off again into the blur of circling bare legs, boot tops, and bon temps all in perfect rhythm to the beating of the bayou heart.

I have lived a fairly long time. I have been places. I have seen bears mate, boats sink, and gila monsters scurry. I have danced till I couldn't stand up and stood up till I couldn't dance. I've eaten bugs, broccoli, and things that crawl on the seafloor. I have seen as far back as Mayan temples, as far away as Betelgeuse, and as deep down as Tom Robbins. I have been on Johnny Carson, the cover of USA Today, and fed the snakes at the Dixie Chicken.

I have held things in my hand that will be here a million years beyond my own existence.

Yet, on that dance floor, I felt a ripple in the universe, a time warp moment when the often unspectacular human race threw its head back and howled at the moon.

Thank you, Napoleon; thank you, Canadiens; and thank you, Shirley Cormier and the all-girl Cajun band. It was a crawfish crabmeat carousel, a seafood boudin Creole belle, an Acadian accordian, heavy water gumbo etouffee, Spanish moss jambalaya, and a Tabasco Popsicle where you suck the head and eat the tail.

My gosh, you can say it again: "Deez gurls ken dance."

It is difficult to find, except in academic circles, practicing veterinarians who have lost their humility. I think it is because of the company we keep. Animals are not respecters of good looks, intelligence, prestigious honors, or fashion sense.

They remind us regularly of our real place in the food chain.

A COLD CALL

Through rain or sleet or snow or hail, the vet's on call to . . . pull it or push it or stop it or start it or pump it or bump it, to hose it or nose it, to stay the course till wellness doth prevail.

It was a cold winter in southern Michigan: -3 degrees. Dr. Lynn the veterinarian got the call after supper from a good client. Their four horses had illegally gained entrance to the tack room and eaten 150 pounds of grain.

She drove out to the magnificently refurbished, snow-covered countryside horse farm of the couple, a pair of upscale twenty-something Internet millionaires. The three crunched their way back to the rustic, unimproved forty-year-old barn where the horses were now in various poses of drooling gastric distress.

A quick auscultation showed no intestinal movement and membranes the color of strawberry-grape Popsicle tongue. Lynn began her work under the one lightbulb. There was no door, but at -3 degrees, who cares. The Banamine was as thick as Miracle Whip, her stomach hose was as rigid as PVC pipe, and her hand stuck to the stainless steel pump. It was so cold her shadow cracked when she stepped on it.

She pumped her patients' stomachs with Epsom salts and mineral oil. One of the horses, however, did not respond. She instructed the couple to walk the horses while she went up to the house to call the surgeon at the vet school. (Even her cell phone had frozen and would only dial odd numbers.)

As she stepped through the back door of the main house, she remembered that the couple had a pair of Akitas named Whiskey and Bear. Surely the dogs aren't loose in the house, Lynn thought, or they would have said something. She dialed the phone on the kitchen wall. As it was ringing, she heard the click-click-click of toenails on the hardwood floor. Around the corner came a massive beast big as a Ford tractor. His sled dog ruff stood straight up on his neck. The curled tail never moved and the gaze was level. "Good dog, Whiskey, good dog . . . I'm just borrowing the phone here. . . ."

Dogs often remember their vet the way children remember their dentist. Whiskey sniffed Lynn's leg.

"Good dog . . . oh, yes, I'd like to speak to--YEOW!"

The au pair staying with the young millionaires heard a screaming clatter. She stepped around the door to be met by Whiskey dragging the good doctor down the hallway by a Carhartt leg, her arms flailing, trailing stethoscope, gloves, stocking cap, syringes, and steamed-up glasses like chum from a trawler. They were stopped when the phone cord came tight.

"Let the nice vet go, Whiskey," the au pair said in a Scandinavian accent. "She's only trying to help."

The difference between city and country can be as gray as a country-pop crossover hit or as black and white as five-buckle overshoes versus tasseled loafers. But when the twain shall meet, you can hear the rubbing of cultural tectonic plates.

AIN'T SEEN NUTHIN' YET

Mick owned a gas station alongside Interstate 80 in Hershey, Nebraska. It was to supplement his "agricultural habit," as he called his farming operation.

One hot afternoon, a sporty vehicle with Massachusetts plates pulled in to gas up. The driver unwound himself from the bucket seat, stood on the gravel, and stretched. He let his gaze travel the full circumference of the horizon around him.

"My gosh!" he said, somewhat overwhelmed, "what do you do out here in the middle of nowhere?"

"We jis' scratch around in the dirt and try to get by," answered Mick.

"This is the most desolate place I've ever been! There's nuthin' here!"

"Where ya goin'?" asked Mick.

"San Francisco."

"On I-80?"

"Yep."

"Well," said Mick, "you ain't seen nuthin' yet."

Where, exactly, is "nuthin'"? According to Mick, it waited for this pilgrim on down the road. It is 638 miles from Hershey to Salt Lake City, the next city with smog on I-80.

In contrast, I-95 runs 430 miles from Boston to Washington, D.C. In between, it passes through Providence, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, all of which are bigger than Salt Lake City.

But after this poor traveler got his transfusion in Salt Lake, nuthin' waited for him farther down the road. Picture 525 miles on I-80 west to Reno with nuthin' but Nevada in between.

Some folks say you might see nuthin' on I-10 from Junction to El Paso, or nuthin' on Hwy. 200 from Great Falls to Glendive, or nuthin' on I-40 on from Flagstaff to Barstow, or Hwy. 20 from Boise to Bend, or nuthin' on Hwy. 43 from Edmonton to Grande Prairie.

In my ramblings, I've seen a lot of nuthin'. It appeals to me; breathin' room, big sky. Matter of fact I've seen nuthin' in busy places like south New Jersey, the Appalachian Trail, the Ozarks, the U.P., or outside Gallipolis. You gotta look a little harder, but it's there. Nuthin', that is.

Mick sold the gas station, but he still lives in Hershey. He says it feels like home.

Feels that way to me, too. There's somethin' about nuthin' I like.

Cowboy stories are strewn with wrecks. Horse wrecks, cow wrecks, financial wrecks, Rex Allen, and Tyrannoeohippus Rex. And although one could make them up, it's not necessary. They are a daily occurrence.

WHEN NATURE CALLS

Russell asked me if I'd ever heard of a flyin' mule. "You mean parachuting Democrats?" I asked.

He and a neighbor had hired a couple of day work cowboys to help round up cows on the Black Range in southeastern Arizona. Billy, one of the cowboys, brought a young mule to "tune up" durin' the weeklong gather. When they had ridden the saddled mule through the Willcox auction ring, he'd looked pretty good. But afterward when Billy went to load him, he got his first inkling that all was not as it appeared.

The sale barn guys had the mule stretched out and lyin' down between a post and a heel rope. "To take the saddle off," they explained. "He's fine once yer mounted, but you can't get near him when yer on the ground!"

First morning of the roundup, Billy managed to get Jughead saddled. He had to rope him and tie a foot up to get it done. Then they all sat around for two hours drinkin' coffee till sunup.

As they left the headquarters at daylight, Billy made arrangements to meet Russell at a visible landmark. With all that coffee he'd been drinkin', he knew a "call of nature" was imminent and he'd need help gettin' back on Jughead.

Billy gathered a handful of critters but missed the landmark. By then his kidneys were floating.

The country was rough and brushy. He spotted a ten-foot scraggly pine on the edge of a four-foot embankment. It gave Billy an idea. Not a good idea, but remember, he was desperate and he was a cowboy.

He dropped his lasso around the saddle horn and rode up next to the tree. He passed the rope around the trunk and dallied onto the horn. The plan was to snug Jughead up close, get off, do his business, then remount.

The plan went awry.

Jughead started buckin' around the tree on the long tether. He made two passes before Billy lost his dally. Brush and cactus, pine boughs, and colorful epithets filled the air! With each ever-tightening circle, the rope climbed higher up the trunk. The higher they climbed, the more time they spent airborne.

Jughead was hoppin' like a kangaroo when the treetop bent and the uppermost coils peeled off. Mule and cowboy were midair when they hit the end of the line. Jughead went down and Billy spilled into the arroyo.

Almost on cue, Russell came crashin' up outta the creek bottom, "Mount up, Billy. We need help!"

Billy's hat was down around his ears, and he looked like he'd bitten off the end of his nose.

"Uh, go ahead and shake the dew off your lily," said Russell generously. "I guess we've got time."

Billy labored to one knee. "Never mind," he said, "I went in flight."

Some commentators just can't leave well enough alone.

ONLY EWES CAN PREVENT WILDFIRE

We have long known the sheep to be a two-purpose animal: meat and wool. Now the Nevada Extension Service is finding another purpose: fire control.

Practicing a technique successfully used in California and British Columbia, the Nevadans are using high-density, short-duration grazing to mow the fire-prone grass and sagebrush.

Their motto is "Only ewes can prevent wildfire."

When I first heard about using sheep in fire control, I had a moment's difficulty picturing the scene. Were they flying in low and dropping woolly beasts on hot spots? Were they fitting lambs with gas masks and shovels, then parachuting them into the forest? Or were sheep serving some useful function at the base camp? Waiting tables, perhaps nursing wounds, or simply offering comfort to the firefighters in the form of a shoulder or fleece to lean on?

No! Of course not. The sheep simply eats everything in sight so that nothing is left to burn.

Pretty clever, these Extension Service people. I understand they might apply for a grant to examine other alternative uses for sheep. I've come up with some possibilities they might test.

Need a replacement for the waterbed? Sleep on a bed of sheep. When trail riding or camping, just bring three or four head along. They can reduce fire danger and you can count them at night.

How about soundproofing? When a teenager pulls up beside you in traffic and his hi-fi-whale communicating car stereo is so loud it makes seismic waves in your 7-Eleven Styrofoam cup, you can immediately dial 922-BRING-A-EWE. An emergency crew will be dispatched to the scene and will stuff sheep inside the teen's car until the sound is properly muffled.

Or how 'bout a safety device in automobiles to replace the airbag? In the event of a crash, a Bag o' Sheep explodes from the dash, absorbing the impact, then escapes out the broken windows.

In a hurry at the airport, but don't have time for a shine? Try the Basque Sheep Buffer. Two strong people from Boise drag a ewe over your boot toes, side to side. They glisten with lanolin, and in a hot dance hall when the grease starts steaming, no tellin' what can happen.

Other things come to mind: sheep as large drain stoppers, self-propelled sponges, or a place to store your extra Velcro.

But the alternative use for sheep that may have the greatest potential: Q-tips for elephants.

There are fourteen definitions derived from this story explained in the glossary of this book.

COWBOY VOCABULARY MISCONCEPTIONS

This piece has an agricultural-cowboy slant. However, I am aware that urban people (Gentiles, I call them) read it as well. So when I lapse into my "cowboy vocabulary," I appreciate that some of my meanings could be unclear. Listed are some common misconceptions:

Statement: "My whole flock has keds."

Misinterpretation: Sheep are now endorsing tennis shoes.

Statement: "I'm looking to buy some replacement heifers, but I want only polled cattle."

Misinterpretation: His cows are being interviewed by George Gallup.

Statement: "I'm going to a gaited horse show."

Misinterpretation: A horse performance being held in an exclusive residential area.

Statement: "I work in a hog confinement facility."

Misinterpretation: She teaches classes in the campus jail at University of Arkansas.

Statement: "I prefer the Tarentaise over the Piedmontese."

Misinterpretation: He is picky about cheese.

Statement: "They've had a lot of blowouts at the turkey farm this year."

Misinterpretation: Sounds like they better change tire dealers.

Statement: "This mule is just a little owly."

Misinterpretation: His ears stick up? He's wise beyond his species limitation? No, wait, he looks like Benjamin Franklin or Wilford Brimley?

From the Hardcover edition.