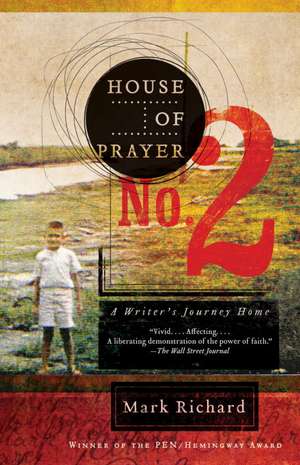

House of Prayer No. 2: A Writer's Journey Home

Autor Mark Richarden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2012

In this irresistible blend of history, travelogue, and personal reflection, Richard draws a remarkable portrait of a writer’s struggle with his faith, the evolution of his art, and the recognition of one’s singularity in the face of painful disability.

Preț: 119.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.87€ • 23.94$ • 18.93£

22.87€ • 23.94$ • 18.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400077779

ISBN-10: 140007777X

Pagini: 201

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 140007777X

Pagini: 201

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Mark Richard is the author of two award-winning short story collections, The Ice at the Bottom of the World and Charity, and the novel Fishboy. His short stories and journalism have appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire, Vogue, and GQ. He is the recipient of the PEN/Hemingway Award, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and a Whiting Foundation Writer’s Award. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and their three sons.

Extras

Say you have a "special child," which in the South means one between Down's and dyslexic. Birth him with his father away on Army maneuvers along East Texas bayous. Give him his only visitor in the military hospital his father's father, a sometime railroad man, sometime hired gun for Huey Long with a Louisiana Special Police badge. Take the infant to Manhattan, Kansas, in winter, where the only visitor is a Chinese Peeping Tom, little yellow face in the windows during the cold nights. Further frighten the mother, age twenty, with the child's convulsions. There's something "different" about this child, the doctors say.

Move the family to Kirbyville, Texas, where the father cruises timber in the big woods. Fill the back porch with things the father brings home: raccoons, lost bird dogs, stacks of saws, and machetes. Give the child a sandbox to play in, in which scorpions build nests. Let the mother cut the grass and run over rattlesnakes, shredding them all over the yard. Make the mother cry and miss her mother. Isolate her from the neighbors because she is poor and Catholic. For playmates, give the child a mongoloid girl who adores him. She is the society doctor's child and is scared of thunder. When it storms, she hides, and only the special child can find her. The doctor's wife comes to the house in desperation. Please help me find my daughter. Here she is, in the culvert, behind a bookcase, in a neighbor's paper tepee. Please come to a party, the doctor's wife sniffs, hugging her daughter. At the party, it goes well for the nervous mother and the forester father until their son bites the arm of a guest and the guest goes to the hospital for stitches and a tetanus shot. The special child can give no reason why.

Move the family to a tobacco county in Southside Virginia. It is the early sixties, and black families still get around on mule and wagon. Corn grows up to the backs of houses even in town. Crosses burn in yards of black families and Catholics. Crew cut the special child's hair in the barbershop where all the talk is of niggers and nigger-lovers. Give the child the responsibility of another playmate, the neighbor two houses down, Dr. Jim. When Dr. Jim was the child's age, Lee left his army at Appomattox. When Dr. Jim falls down between the corn rows he is always hoeing, the child must run for help. Sometimes the child just squats beside Dr. Jim sprawled in the corn and listens to Dr. Jim talking to the sun. Sometimes in the orange and grey dust when the world is empty, the child lies in the cold backyard grass and watches the thousands of starlings swarm Dr. Jim's chimneys, and the child feels like he is dying in an empty world.

The child is five years old.

Downstairs in the house the family shares is a rough redneck, a good man who brought a war bride home from Italy. The war bride thought the man was American royalty because his name was Prince. Prince was just the man's name. The Italian war bride is beautiful and has borne two daughters, the younger is the special child's age. The elder is a teenager who will soon die of a blood disease. The beautiful Italian wife and the special child's mother smoke Salems and drink Pepsi and cry together on the back steps. They both miss their mothers. In the evening Prince comes home from selling Pontiacs, and the forester father comes home from the forest, and they drink beer together and wonder about their wives. They take turns mowing the grass around the house.

The company the father works for is clearing the land of trees. The father finds himself clearing the forests off the old battlefields from the Civil War. The earthworks are still there, stuff is still just lying around. He comes home with his pockets full of minie balls. He buys a mine detector from an Army surplus store, and the family spends weekends way deep in the woods. One whole Sunday the father and the mother spend the day digging and digging, finally unearthing a cannon-sized piece of iron agate. The mother stays home after that. On Sunday nights she calls her mother in Louisiana and begs to come home. No, her mother says. You stay. She says this in Cajun French.

The little girl downstairs is named Debbie. The special child and Debbie play under the big pecan tree where the corn crowds the yard. One day the special child makes nooses and hangs all of Debbie's dolls from the lower limbs of the tree. Debbie runs crying inside. Estelle, the big black maid, shouts from the back door at the special child to cut the baby dolls down, but she doesn't come out in the yard to make him do this and he does not. She is frightened of the special child, and he knows this. If he concentrates hard enough, he can make it rain knives on people's heads.

Maybe it would be best if something were done with the special child. The mother and father send him to kindergarten across town, where the good folk live. The father has saved his money and has bought a lot to build a house there, across from the General Electric Appliance dealer. Because he spent all his money on the lot, the father has to clear the land himself. He borrows a bulldozer from the timber company and "borrows" some dynamite. One Saturday he accidentally sets the bulldozer on fire. One Sunday he uses too much dynamite to clear a stump and cracks the foundation of the General Electric Appliance dealer's house. The father decides not to build in that neighborhood after all.

In the kindergarten in that part of town there are records the teacher whom the special child calls Miss Perk lets him play over and over. When the other kids lie on rugs for their naps, she lets him look at her books. During reading hour he sits so close to her that she has to wrap him in her arms while she holds the book. The best stories are the ones Miss Perk tells the class herself. About the little girl whose family was murdered on a boat and the criminals tried to sink the boat. The little girl saw water coming in the portholes, but she thought the criminals were just mopping the decks and doing a sloppy job. Miss Perk told about the car wreck she saw that was so bloody she dropped a pen on the floor of her car for her son to fetch so he wouldn't have to see the man with the top of his head ripped off like he had been scalped. On Fridays is Show-and-Tell, and the special child always brings the same thing in for Show-and-Tell, his cat Mr. Priss. Mr. Priss is a huge, mean tomcat that kills other cats and only lets the special child near him. The special child dresses Mr. Priss in Debbie's baby doll clothes, especially a yellow raincoat and yellow sou'wester-style rain hat. Then the special child carries Mr. Priss around for hours in a small suitcase. When his mother asks if he has the cat in the suitcase again, the special child always says, No, ma'am.

Miss Perk says the way the other children follow the special child around, that the special child will be something someday, but she doesn't say what.

The father and the mother meet some new people. There is a new barber and his wife. The new barber plays the guitar in the kitchen and sings Smoke! Smoke! Smoke that cigarette! He is handsome and wears so much oil in his hair that it stains the sofa when he throws back his head to laugh. He likes to laugh a lot. His wife teaches the mother how to dance, how to do the Twist. There is another new couple in town, a local boy, sort of a black sheep, from country folk, who went away to Southeast Asia to be a flight surgeon and is back with his second or third wife, nobody knows for sure. At the reckless doctor's apartment, they drink beer and do the Twist and listen to Smothers Brothers albums. They burn candles stuck in Chianti bottles. The special child is always along because there is no money for a babysitter and Estelle will not babysit the special child. One night the special child pulls down a book off the doctor's shelf and begins to slowly read aloud from it. The party stops. It is a college book about chemicals. In two more months the child will start first grade.

At first, first grade is empty. Most of the children are bringing in the tobacco harvest. The ones who show up are mostly barefoot and dirty and sleep with their heads on the desk all day. A lot of them have fleas and head lice. Most of them have been up all night tying tobacco sticks, their hands are stained black with nicotine.

At first, first grade makes no sense to the special child. The child wants to get to the books, but the books are for later, the teacher tells him. You must learn the alphabet first. But the child has learned the alphabet already; Miss Perk taught him the letters perched in her lap at her desk when the other children napped, and he taught himself how they fit together to make words sitting close to her as she read from children's books and Life magazine. The special child thought the tobacco children had the right idea, so he put his head on his desk and slept through the As and the Bs and the Cs.

He won't learn, he doesn't learn, he can't learn, the teachers tell the mother. He talks back to his teachers, tries to correct their speech. He was rude to kind Mr. Clary when he came to show the class some magic tricks. You better get him tested. He might be retarded. And he runs funny.

The special child is supposed to be playing at the General Electric Appliance dealer's house with his son David. The son has a tube you blow into and a Mercury capsule shoots up in the air and floats down on a plastic parachute. The special child may have to steal it, but first he decides to go to visit Miss Perk's. Maybe she has a book or something. Miss Perk does not disappoint. She is glad to see the special child. She tells him that the Russians send men up in Mercury-capsule things and don't let them come back down. She says if you tune your radio in just right, you can hear their heartbeats stop. She says if you ever see a red light in the night sky, it's a dead Russian circling the earth forever. Can I come back and be in your school, Miss Perk? No, you're too big now. Go home.

Back at the General Electric Appliance dealer's house there's nobody home. It is too far to walk home, so the child lies in the cold grass and watches the grey and orange dusk. At dark, his life will be over. There is a gunshot off in a clay field a ways away, and something like a rocket-fast bumblebee whizzes through the air and thuds into the ground beside the special child. He stays real still. There's not another one. The child is beginning to learn that things can happen to you that would upset the world if you told about them. He doesn't tell anyone about the thing that buzzed and thumped into the ground by his head.

Y'all should do something with that child, people say. The mother takes the child to Cub Scouts. For the talent show, the mother makes a wig out of brown yarn, and the special child memorizes John F. Kennedy's inaugural speech. They laugh at the child in the wig at the show until he begins his speech. Afterward, there's a lecture on drinking water from the back of the toilet after an atom bomb lands on your town, and everybody practices crawling under tables. For weeks afterward, people stop the child and ask him to do the Kennedy thing until finally somebody shoots Kennedy in Texas and the child doesn't have to perform at beer parties and on the sidewalk in front of the grocery store anymore.

The mother starts crying watching the Kennedy funeral on the big TV the father bought to lift her spirits. She doesn't stop. The mother won't get out of bed except to cry while she makes little clothes on her sewing machine. She keeps losing babies, and her mother still won't let her come home. The father sends for the mother's sister. They pack a Thanksgiving lunch and drive to Appomattox to look at the battlefields. It rains and then snows, and they eat turkey and drink wine in the battlefield parking lot. The mother is happy, and the father buys the special child a Confederate hat. After the sister leaves, the mother loses another baby. The father brings the special child another beagle puppy home. The first one, Mud Puddle, ran away in Texas after the father drove it from Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Kirbyville, Texas, strapped to the roof of the car. He had sedated it, he tried to tell people who were nosy along the way. When they got to Texas, there were bugs stuck all in its front teeth like a car grille. When the dog woke completely up, it ran away.

This new dog, in Virginia, the special child calls Hamburger. The mother cries when she sees it in the paper sack. Maybe we need to meet some more friends, the father tells the mother. Okay, the mother says, and wipes her eyes. She always does what her husband tells her to do. She is trying to be a good wife.

There's the big German, Gunther, with the thick accent and his wife who manage the dairy on the edge of town. They have a German shepherd named Blitz who does whatever Gunther tells it to do. The special child is frightened of the vats of molasses Gunther uses to feed the cows. The child is more interested in the caricatures down in the cellar of Gunther's old house. Gunther's old house was a speakeasy, and someone drew colorful portraits of the clandestine drinkers on the plaster wall behind the bar. They look like people in town, says the special child. It's because the cartoons are the fathers of people in town, says his father.

Gunther's wife finds the special child lying in the cold grass of a pasture watching the sun dissolve in the orange and grey dusk. You shouldn't do that, she tells him. If an ant crawls in your ear, it'll build a nest and your brain will be like an ant farm and it'll make you go insane.

Later, Gunther falls into a silage bin, and his body is shredded into pieces the size a cow could chew as cud.

The timber company gives the father a partner so they can reseed the thousands of acres of forests they are clear-cutting down to nothing. Another German. The German knows everything, just ask him, the father says. The German and his wife have two children the special child is supposed to play with. Freddie was the boy’s name. Once, when the special child was spending the night, a hurricane came, and Freddie wet the bed and blamed it on the special child. After that, the special child broke a lot of expensive windup cars and trains from the Old Country.

From the helicopter the father uses to reseed the forests farther south, you can still see Sherman’s March to the Sea, the old burnage in new-growth trees, the bright cities that have sprung from the towns the drunken Federal troops torched. Yah, yah, zat iss in der past, says the German, you must let it go.

The father and the German are in North Carolina cutting timber in the bottom of a lake; the dam to make the lake isn’t finished yet. The father and the German have become good friends. Sometimes they do their work way back in the deep country away from company supervisors, and sometimes they walk through empty old houses on land their company has bought for timber rights. In the attics they fi nd rare books, old stamps, Confederate money. One day eating lunch in the bottom of the lake, the father and the German fi gure how much more timber has to be cut before the water will reach the shore. The father then says, You know, if you were able to figure exactly where the shoreline will be, and buy that land, you could make a small fortune.

On the weekends, they break their promises to picnic with their families at Indian caves they have found and ride everybody around on the bush motorcycles they use to put out forest fires. Instead, the father and the German spend every extra hour of daylight cutting sight lines with machetes, dragging “borrowed” surveying equipment, and measuring chains around the edge of the empty lake.

The money they give the old black sharecropper for the secret shoreline is all the money they can scrape out of their

savings and their banks. The old black sharecropper accepts the first offer the father and the German make on the land left to him by his daddy. Most of the shoreline property they buy from the timber company, but they need an access road through the old black sharecropper’s front yard, past his shack. Everyone knows the lake is coming, but the father and the German don’t tell the black sharecropper the size of their shoreline purchase, just as the sharecropper doesn’t tell them he has also eyeballed where the shoreline will appear and is going to use their money to build the state’s fi rst black marina with jukeboxes and barbeque pits right next to their subdivision. He doesn’t tell them they just gave him the seed money to build H. W. Huff ’s Marina and Playland.

Twenty acres of waterfront property, two points with a long, clay, slippery cove between them when the dam closes and the lake floods. The German gets his choice of which half of the property is his because he was somehow able to put up ten percent more money at the last minute. He chooses the largest point, the one with sandy beaches all around it. The father gets the wet, slippery clay bank and muddy point. The father tells the mother it is time to meet some new friends.

Meet the American Oil dealer, the one with the pretty wife from Coinjock, North Carolina, a wide grin, and a Big Daddy

next door. Down in the basement of his brand- new brick home on a brick mantel the oil dealer has a little ship he put together in college. Most people, if they were even guessing, foot up near the fire, glass leaning with bourbon, take the little model to be a Viking ship. It is not a Viking ship even though little fur-tuniced men seated along both rails pull oars beneath a colorful sail. Who is that man tied to the mast? asks the special child. Upstairs the adults play Monopoly in the kitchen and drink beer until the father drinks a lot of beer and begins to complain about Sherman’s March, and Germans, and it is time to go home.

Later on, the special child is guarding his house with his Confederate hat and wooden musket while his mother and father are at the hospital having a baby. The oil dealer drives over in his big car and spends the afternoon with the special child. He has a paper sack full of Japanese soldiers you shoot into the air with a slingshot and they parachute into the shrubbery. He shows the special child how to make a throw-down bomb with matchheads and two bolts, but best of all, in a shoe box he has brought the special child the little ship off the brick mantel and tells him who

Ulysses was. It is a good story. The only part of the story the child does not quite believe is that somehow Ulysses was older than Jesus. He doesn’t say anything to the oil dealer, because the oil dealer was being nice, but he will have to ask Miss Perk about that later.

Here’s some pieces that have come off the ship over the years, the oil dealer says. There are a couple of Ulysses’ men in his shirt pocket. Thank you, says the child. The child spends the weekend at the oil dealer’s house with his wife and children waiting for his mother and father to come home from the hospital empty-handed again.

From the Hardcover edition.

Move the family to Kirbyville, Texas, where the father cruises timber in the big woods. Fill the back porch with things the father brings home: raccoons, lost bird dogs, stacks of saws, and machetes. Give the child a sandbox to play in, in which scorpions build nests. Let the mother cut the grass and run over rattlesnakes, shredding them all over the yard. Make the mother cry and miss her mother. Isolate her from the neighbors because she is poor and Catholic. For playmates, give the child a mongoloid girl who adores him. She is the society doctor's child and is scared of thunder. When it storms, she hides, and only the special child can find her. The doctor's wife comes to the house in desperation. Please help me find my daughter. Here she is, in the culvert, behind a bookcase, in a neighbor's paper tepee. Please come to a party, the doctor's wife sniffs, hugging her daughter. At the party, it goes well for the nervous mother and the forester father until their son bites the arm of a guest and the guest goes to the hospital for stitches and a tetanus shot. The special child can give no reason why.

Move the family to a tobacco county in Southside Virginia. It is the early sixties, and black families still get around on mule and wagon. Corn grows up to the backs of houses even in town. Crosses burn in yards of black families and Catholics. Crew cut the special child's hair in the barbershop where all the talk is of niggers and nigger-lovers. Give the child the responsibility of another playmate, the neighbor two houses down, Dr. Jim. When Dr. Jim was the child's age, Lee left his army at Appomattox. When Dr. Jim falls down between the corn rows he is always hoeing, the child must run for help. Sometimes the child just squats beside Dr. Jim sprawled in the corn and listens to Dr. Jim talking to the sun. Sometimes in the orange and grey dust when the world is empty, the child lies in the cold backyard grass and watches the thousands of starlings swarm Dr. Jim's chimneys, and the child feels like he is dying in an empty world.

The child is five years old.

Downstairs in the house the family shares is a rough redneck, a good man who brought a war bride home from Italy. The war bride thought the man was American royalty because his name was Prince. Prince was just the man's name. The Italian war bride is beautiful and has borne two daughters, the younger is the special child's age. The elder is a teenager who will soon die of a blood disease. The beautiful Italian wife and the special child's mother smoke Salems and drink Pepsi and cry together on the back steps. They both miss their mothers. In the evening Prince comes home from selling Pontiacs, and the forester father comes home from the forest, and they drink beer together and wonder about their wives. They take turns mowing the grass around the house.

The company the father works for is clearing the land of trees. The father finds himself clearing the forests off the old battlefields from the Civil War. The earthworks are still there, stuff is still just lying around. He comes home with his pockets full of minie balls. He buys a mine detector from an Army surplus store, and the family spends weekends way deep in the woods. One whole Sunday the father and the mother spend the day digging and digging, finally unearthing a cannon-sized piece of iron agate. The mother stays home after that. On Sunday nights she calls her mother in Louisiana and begs to come home. No, her mother says. You stay. She says this in Cajun French.

The little girl downstairs is named Debbie. The special child and Debbie play under the big pecan tree where the corn crowds the yard. One day the special child makes nooses and hangs all of Debbie's dolls from the lower limbs of the tree. Debbie runs crying inside. Estelle, the big black maid, shouts from the back door at the special child to cut the baby dolls down, but she doesn't come out in the yard to make him do this and he does not. She is frightened of the special child, and he knows this. If he concentrates hard enough, he can make it rain knives on people's heads.

Maybe it would be best if something were done with the special child. The mother and father send him to kindergarten across town, where the good folk live. The father has saved his money and has bought a lot to build a house there, across from the General Electric Appliance dealer. Because he spent all his money on the lot, the father has to clear the land himself. He borrows a bulldozer from the timber company and "borrows" some dynamite. One Saturday he accidentally sets the bulldozer on fire. One Sunday he uses too much dynamite to clear a stump and cracks the foundation of the General Electric Appliance dealer's house. The father decides not to build in that neighborhood after all.

In the kindergarten in that part of town there are records the teacher whom the special child calls Miss Perk lets him play over and over. When the other kids lie on rugs for their naps, she lets him look at her books. During reading hour he sits so close to her that she has to wrap him in her arms while she holds the book. The best stories are the ones Miss Perk tells the class herself. About the little girl whose family was murdered on a boat and the criminals tried to sink the boat. The little girl saw water coming in the portholes, but she thought the criminals were just mopping the decks and doing a sloppy job. Miss Perk told about the car wreck she saw that was so bloody she dropped a pen on the floor of her car for her son to fetch so he wouldn't have to see the man with the top of his head ripped off like he had been scalped. On Fridays is Show-and-Tell, and the special child always brings the same thing in for Show-and-Tell, his cat Mr. Priss. Mr. Priss is a huge, mean tomcat that kills other cats and only lets the special child near him. The special child dresses Mr. Priss in Debbie's baby doll clothes, especially a yellow raincoat and yellow sou'wester-style rain hat. Then the special child carries Mr. Priss around for hours in a small suitcase. When his mother asks if he has the cat in the suitcase again, the special child always says, No, ma'am.

Miss Perk says the way the other children follow the special child around, that the special child will be something someday, but she doesn't say what.

The father and the mother meet some new people. There is a new barber and his wife. The new barber plays the guitar in the kitchen and sings Smoke! Smoke! Smoke that cigarette! He is handsome and wears so much oil in his hair that it stains the sofa when he throws back his head to laugh. He likes to laugh a lot. His wife teaches the mother how to dance, how to do the Twist. There is another new couple in town, a local boy, sort of a black sheep, from country folk, who went away to Southeast Asia to be a flight surgeon and is back with his second or third wife, nobody knows for sure. At the reckless doctor's apartment, they drink beer and do the Twist and listen to Smothers Brothers albums. They burn candles stuck in Chianti bottles. The special child is always along because there is no money for a babysitter and Estelle will not babysit the special child. One night the special child pulls down a book off the doctor's shelf and begins to slowly read aloud from it. The party stops. It is a college book about chemicals. In two more months the child will start first grade.

At first, first grade is empty. Most of the children are bringing in the tobacco harvest. The ones who show up are mostly barefoot and dirty and sleep with their heads on the desk all day. A lot of them have fleas and head lice. Most of them have been up all night tying tobacco sticks, their hands are stained black with nicotine.

At first, first grade makes no sense to the special child. The child wants to get to the books, but the books are for later, the teacher tells him. You must learn the alphabet first. But the child has learned the alphabet already; Miss Perk taught him the letters perched in her lap at her desk when the other children napped, and he taught himself how they fit together to make words sitting close to her as she read from children's books and Life magazine. The special child thought the tobacco children had the right idea, so he put his head on his desk and slept through the As and the Bs and the Cs.

He won't learn, he doesn't learn, he can't learn, the teachers tell the mother. He talks back to his teachers, tries to correct their speech. He was rude to kind Mr. Clary when he came to show the class some magic tricks. You better get him tested. He might be retarded. And he runs funny.

The special child is supposed to be playing at the General Electric Appliance dealer's house with his son David. The son has a tube you blow into and a Mercury capsule shoots up in the air and floats down on a plastic parachute. The special child may have to steal it, but first he decides to go to visit Miss Perk's. Maybe she has a book or something. Miss Perk does not disappoint. She is glad to see the special child. She tells him that the Russians send men up in Mercury-capsule things and don't let them come back down. She says if you tune your radio in just right, you can hear their heartbeats stop. She says if you ever see a red light in the night sky, it's a dead Russian circling the earth forever. Can I come back and be in your school, Miss Perk? No, you're too big now. Go home.

Back at the General Electric Appliance dealer's house there's nobody home. It is too far to walk home, so the child lies in the cold grass and watches the grey and orange dusk. At dark, his life will be over. There is a gunshot off in a clay field a ways away, and something like a rocket-fast bumblebee whizzes through the air and thuds into the ground beside the special child. He stays real still. There's not another one. The child is beginning to learn that things can happen to you that would upset the world if you told about them. He doesn't tell anyone about the thing that buzzed and thumped into the ground by his head.

Y'all should do something with that child, people say. The mother takes the child to Cub Scouts. For the talent show, the mother makes a wig out of brown yarn, and the special child memorizes John F. Kennedy's inaugural speech. They laugh at the child in the wig at the show until he begins his speech. Afterward, there's a lecture on drinking water from the back of the toilet after an atom bomb lands on your town, and everybody practices crawling under tables. For weeks afterward, people stop the child and ask him to do the Kennedy thing until finally somebody shoots Kennedy in Texas and the child doesn't have to perform at beer parties and on the sidewalk in front of the grocery store anymore.

The mother starts crying watching the Kennedy funeral on the big TV the father bought to lift her spirits. She doesn't stop. The mother won't get out of bed except to cry while she makes little clothes on her sewing machine. She keeps losing babies, and her mother still won't let her come home. The father sends for the mother's sister. They pack a Thanksgiving lunch and drive to Appomattox to look at the battlefields. It rains and then snows, and they eat turkey and drink wine in the battlefield parking lot. The mother is happy, and the father buys the special child a Confederate hat. After the sister leaves, the mother loses another baby. The father brings the special child another beagle puppy home. The first one, Mud Puddle, ran away in Texas after the father drove it from Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Kirbyville, Texas, strapped to the roof of the car. He had sedated it, he tried to tell people who were nosy along the way. When they got to Texas, there were bugs stuck all in its front teeth like a car grille. When the dog woke completely up, it ran away.

This new dog, in Virginia, the special child calls Hamburger. The mother cries when she sees it in the paper sack. Maybe we need to meet some more friends, the father tells the mother. Okay, the mother says, and wipes her eyes. She always does what her husband tells her to do. She is trying to be a good wife.

There's the big German, Gunther, with the thick accent and his wife who manage the dairy on the edge of town. They have a German shepherd named Blitz who does whatever Gunther tells it to do. The special child is frightened of the vats of molasses Gunther uses to feed the cows. The child is more interested in the caricatures down in the cellar of Gunther's old house. Gunther's old house was a speakeasy, and someone drew colorful portraits of the clandestine drinkers on the plaster wall behind the bar. They look like people in town, says the special child. It's because the cartoons are the fathers of people in town, says his father.

Gunther's wife finds the special child lying in the cold grass of a pasture watching the sun dissolve in the orange and grey dusk. You shouldn't do that, she tells him. If an ant crawls in your ear, it'll build a nest and your brain will be like an ant farm and it'll make you go insane.

Later, Gunther falls into a silage bin, and his body is shredded into pieces the size a cow could chew as cud.

The timber company gives the father a partner so they can reseed the thousands of acres of forests they are clear-cutting down to nothing. Another German. The German knows everything, just ask him, the father says. The German and his wife have two children the special child is supposed to play with. Freddie was the boy’s name. Once, when the special child was spending the night, a hurricane came, and Freddie wet the bed and blamed it on the special child. After that, the special child broke a lot of expensive windup cars and trains from the Old Country.

From the helicopter the father uses to reseed the forests farther south, you can still see Sherman’s March to the Sea, the old burnage in new-growth trees, the bright cities that have sprung from the towns the drunken Federal troops torched. Yah, yah, zat iss in der past, says the German, you must let it go.

The father and the German are in North Carolina cutting timber in the bottom of a lake; the dam to make the lake isn’t finished yet. The father and the German have become good friends. Sometimes they do their work way back in the deep country away from company supervisors, and sometimes they walk through empty old houses on land their company has bought for timber rights. In the attics they fi nd rare books, old stamps, Confederate money. One day eating lunch in the bottom of the lake, the father and the German fi gure how much more timber has to be cut before the water will reach the shore. The father then says, You know, if you were able to figure exactly where the shoreline will be, and buy that land, you could make a small fortune.

On the weekends, they break their promises to picnic with their families at Indian caves they have found and ride everybody around on the bush motorcycles they use to put out forest fires. Instead, the father and the German spend every extra hour of daylight cutting sight lines with machetes, dragging “borrowed” surveying equipment, and measuring chains around the edge of the empty lake.

The money they give the old black sharecropper for the secret shoreline is all the money they can scrape out of their

savings and their banks. The old black sharecropper accepts the first offer the father and the German make on the land left to him by his daddy. Most of the shoreline property they buy from the timber company, but they need an access road through the old black sharecropper’s front yard, past his shack. Everyone knows the lake is coming, but the father and the German don’t tell the black sharecropper the size of their shoreline purchase, just as the sharecropper doesn’t tell them he has also eyeballed where the shoreline will appear and is going to use their money to build the state’s fi rst black marina with jukeboxes and barbeque pits right next to their subdivision. He doesn’t tell them they just gave him the seed money to build H. W. Huff ’s Marina and Playland.

Twenty acres of waterfront property, two points with a long, clay, slippery cove between them when the dam closes and the lake floods. The German gets his choice of which half of the property is his because he was somehow able to put up ten percent more money at the last minute. He chooses the largest point, the one with sandy beaches all around it. The father gets the wet, slippery clay bank and muddy point. The father tells the mother it is time to meet some new friends.

Meet the American Oil dealer, the one with the pretty wife from Coinjock, North Carolina, a wide grin, and a Big Daddy

next door. Down in the basement of his brand- new brick home on a brick mantel the oil dealer has a little ship he put together in college. Most people, if they were even guessing, foot up near the fire, glass leaning with bourbon, take the little model to be a Viking ship. It is not a Viking ship even though little fur-tuniced men seated along both rails pull oars beneath a colorful sail. Who is that man tied to the mast? asks the special child. Upstairs the adults play Monopoly in the kitchen and drink beer until the father drinks a lot of beer and begins to complain about Sherman’s March, and Germans, and it is time to go home.

Later on, the special child is guarding his house with his Confederate hat and wooden musket while his mother and father are at the hospital having a baby. The oil dealer drives over in his big car and spends the afternoon with the special child. He has a paper sack full of Japanese soldiers you shoot into the air with a slingshot and they parachute into the shrubbery. He shows the special child how to make a throw-down bomb with matchheads and two bolts, but best of all, in a shoe box he has brought the special child the little ship off the brick mantel and tells him who

Ulysses was. It is a good story. The only part of the story the child does not quite believe is that somehow Ulysses was older than Jesus. He doesn’t say anything to the oil dealer, because the oil dealer was being nice, but he will have to ask Miss Perk about that later.

Here’s some pieces that have come off the ship over the years, the oil dealer says. There are a couple of Ulysses’ men in his shirt pocket. Thank you, says the child. The child spends the weekend at the oil dealer’s house with his wife and children waiting for his mother and father to come home from the hospital empty-handed again.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Vivid. . . . Affecting. . . . A liberating demonstration of the power of faith.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“An absorbing account of growing up in the 1960s South, living with a disability, becoming a writer and finding faith. Richard’s book attests to the power of words (and the Word) in shaping a life. . . . Richard is a fiercely gifted writer. . . . [His] special childhood results in considerable powers of observation, empathy and imagination.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“So varied, dramatic, and, at times, incredible that it is bound to leave almost every reader with the feeling that they haven’t lived at all.”

—The New Yorker

“Entrancing. . . . A surprising page turner. . . . Richard’s prose is gorgeous—and hits with a force that sometimes stuns. . . . Where other memoirists—evangelical and/or literary—just bluff and brag, he makes art.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Amazing. . . . You’ll know just after two pages of Richard’s effortlessly killer prose that he’s special all right. . . . Grade: A.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Mark Richard’s memoir, House of Prayer No.2, is the finest book he’s ever written. No one writes like him. His prose style is both hammerblow and shrapnel. He has written the book of his life.”

—Pat Conroy

“A lyrical distillation of observations from Richard’s boyhood in and out of southern charity hospitals to his becoming a writer and father in search of faith.”

—Vanity Fair

“Hauntingly beautiful. . . . A quintessentially American story.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A surreal and poetic memoir about faith, self-discovery and forming an artistic inner life.”

—The Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, VA)

“A humorous and heartfelt memoir, never tedious and often lyrical.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“This book is the extraordinary story of a special child who grew up to be a writer, and who may yet—I’m guessing—become a preacher or a priest. There are similar life stories in the South and elsewhere. But few will be written with Richard’s powerful talent, his genius.”

—Clyde Edgerton, Garden & Gun

“Gritty and engrossing. . . . His is an account, at times exquisite, of a youth laced with pain, surgeries, body casts, beatings, fear, drinking, isolation, rebellion. With flashes of brilliance. With mysticism and the supernatural and strokes of what many would call luck. . . . An interesting, well-crafted narrative girded with compassion and feeling, this is a good read.”

—The Virginian-Pilot

“Lovely. . . . Richard captures what is often misunderstood about the Southerner’s intimate parlay with God. Appearances to the contrary, it is not about certainty. . . . A fascinating journey.”

—The Oregonian

“Hot damn! And Glory be! Both. This is a wonderful book.”

—Roy Blount, Jr.

“Supremely animated. . . . [Richard’s] spiritual journey, conducted in fits and starts and finally claimed in gorgeous hosannas of prose, forms the book’s narrative DNA.”

—Elle

“Richard’s story is inspirational not because of conventional redemption or simple answers to his struggle, but because he is so honest about both his doubt and his openness to a wide variety of God’s manifestations.”

—Darcey Steinke, Los Angeles Review of Books

“Affecting. . . . Fans who have been waiting to hear from him ever since [Charity] won’t be disappointed with his new memoir, which sees the welcome return of Richard’s charismatic prose style.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“The precision of the descriptions is marvelous in this memoir of growing up with infirmity. The depth of Richard’s heart is profound, exhilarating, frightening, instructive. House of Prayer

No. 2 is a work of high art.”

—Rick Bass

“Mark Richard says important things about finding one’s way, about love in action, about being a father, and he does so with the precision and grace of an artisan from another time. This is some of the finest writing you will ever read.”

—Amy Hempel

“If Mark Richard could not write, you could not read this. Since he can, you can’t not read it. It is unreal, and Mr. Richard has the wit to make it real.”

—Padgett Powell

—The Wall Street Journal

“An absorbing account of growing up in the 1960s South, living with a disability, becoming a writer and finding faith. Richard’s book attests to the power of words (and the Word) in shaping a life. . . . Richard is a fiercely gifted writer. . . . [His] special childhood results in considerable powers of observation, empathy and imagination.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“So varied, dramatic, and, at times, incredible that it is bound to leave almost every reader with the feeling that they haven’t lived at all.”

—The New Yorker

“Entrancing. . . . A surprising page turner. . . . Richard’s prose is gorgeous—and hits with a force that sometimes stuns. . . . Where other memoirists—evangelical and/or literary—just bluff and brag, he makes art.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Amazing. . . . You’ll know just after two pages of Richard’s effortlessly killer prose that he’s special all right. . . . Grade: A.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Mark Richard’s memoir, House of Prayer No.2, is the finest book he’s ever written. No one writes like him. His prose style is both hammerblow and shrapnel. He has written the book of his life.”

—Pat Conroy

“A lyrical distillation of observations from Richard’s boyhood in and out of southern charity hospitals to his becoming a writer and father in search of faith.”

—Vanity Fair

“Hauntingly beautiful. . . . A quintessentially American story.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A surreal and poetic memoir about faith, self-discovery and forming an artistic inner life.”

—The Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, VA)

“A humorous and heartfelt memoir, never tedious and often lyrical.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“This book is the extraordinary story of a special child who grew up to be a writer, and who may yet—I’m guessing—become a preacher or a priest. There are similar life stories in the South and elsewhere. But few will be written with Richard’s powerful talent, his genius.”

—Clyde Edgerton, Garden & Gun

“Gritty and engrossing. . . . His is an account, at times exquisite, of a youth laced with pain, surgeries, body casts, beatings, fear, drinking, isolation, rebellion. With flashes of brilliance. With mysticism and the supernatural and strokes of what many would call luck. . . . An interesting, well-crafted narrative girded with compassion and feeling, this is a good read.”

—The Virginian-Pilot

“Lovely. . . . Richard captures what is often misunderstood about the Southerner’s intimate parlay with God. Appearances to the contrary, it is not about certainty. . . . A fascinating journey.”

—The Oregonian

“Hot damn! And Glory be! Both. This is a wonderful book.”

—Roy Blount, Jr.

“Supremely animated. . . . [Richard’s] spiritual journey, conducted in fits and starts and finally claimed in gorgeous hosannas of prose, forms the book’s narrative DNA.”

—Elle

“Richard’s story is inspirational not because of conventional redemption or simple answers to his struggle, but because he is so honest about both his doubt and his openness to a wide variety of God’s manifestations.”

—Darcey Steinke, Los Angeles Review of Books

“Affecting. . . . Fans who have been waiting to hear from him ever since [Charity] won’t be disappointed with his new memoir, which sees the welcome return of Richard’s charismatic prose style.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“The precision of the descriptions is marvelous in this memoir of growing up with infirmity. The depth of Richard’s heart is profound, exhilarating, frightening, instructive. House of Prayer

No. 2 is a work of high art.”

—Rick Bass

“Mark Richard says important things about finding one’s way, about love in action, about being a father, and he does so with the precision and grace of an artisan from another time. This is some of the finest writing you will ever read.”

—Amy Hempel

“If Mark Richard could not write, you could not read this. Since he can, you can’t not read it. It is unreal, and Mr. Richard has the wit to make it real.”

—Padgett Powell