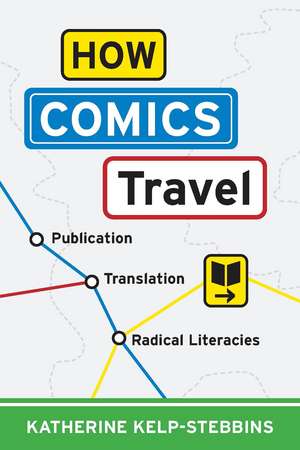

How Comics Travel: Publication, Translation, Radical Literacies: Studies in Comics and Cartoons

Autor Katherine Kelp-Stebbinsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 mar 2022

Honorable Mention, 2023 CSS Charles Hatfield Book Prize

In How Comics Travel: Publication, Translation, Radical Literacies, Katherine Kelp-Stebbins challenges the clichéd understanding of comics as a “universal” language, circulating without regard for cultures or borders. Instead, she develops a new methodology of reading for difference. Kelp-Stebbins’s anticolonial, feminist, and antiracist analytical framework engages with comics as sites of struggle over representation in a diverse world. Through comparative case studies of Metro, Tintin, Persepolis, and more, she explores the ways in which graphic narratives locate and dislocate readers in every phase of a transnational comic’s life cycle according to distinct visual, linguistic, and print cultures. How Comics Travel disengages from the constrictive pressures of nationalism and imperialism, both in comics studies and world literature studies more broadly, to offer a new vision of how comics depict and enact the world as a transcultural space.

Din seria Studies in Comics and Cartoons

-

Preț: 353.84 lei

Preț: 353.84 lei -

Preț: 352.08 lei

Preț: 352.08 lei -

Preț: 270.71 lei

Preț: 270.71 lei -

Preț: 280.83 lei

Preț: 280.83 lei -

Preț: 270.34 lei

Preț: 270.34 lei -

Preț: 273.46 lei

Preț: 273.46 lei -

Preț: 306.24 lei

Preț: 306.24 lei -

Preț: 336.74 lei

Preț: 336.74 lei -

Preț: 332.26 lei

Preț: 332.26 lei -

Preț: 356.60 lei

Preț: 356.60 lei -

Preț: 319.84 lei

Preț: 319.84 lei -

Preț: 255.27 lei

Preț: 255.27 lei -

Preț: 272.32 lei

Preț: 272.32 lei -

Preț: 296.95 lei

Preț: 296.95 lei -

Preț: 295.72 lei

Preț: 295.72 lei -

Preț: 260.07 lei

Preț: 260.07 lei -

Preț: 256.00 lei

Preț: 256.00 lei -

Preț: 278.27 lei

Preț: 278.27 lei

Preț: 266.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 400

Preț estimativ în valută:

51.05€ • 52.98$ • 42.67£

51.05€ • 52.98$ • 42.67£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814258231

ISBN-10: 0814258239

Pagini: 238

Ilustrații: 19 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Studies in Comics and Cartoons

ISBN-10: 0814258239

Pagini: 238

Ilustrații: 19 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Studies in Comics and Cartoons

Recenzii

“In focusing on place in comics, Kelp-Stebbins generates beautifully situated readings, carefully contextualized by bringing background issues such as publishing practices, translatability, and creators’ commentary to bear. This demonstration of how to interpret comics in a global context is one step toward decolonizing the discipline. This book is a pleasure to read, with revelations in every chapter.” —Barbara Postema, author of Narrative Structure in Comics: Making Sense of Fragments

“Kelp-Stebbins presents a refreshing new analysis filled with nuance and depth, which takes a comparative approach to comics from one national context to another. An extraordinary, groundbreaking work that should inspire a global audience of comics scholars.” —Martha B. Kuhlman, coeditor of The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing Is a Way of Thinking

“Kelp-Stebbins presents a refreshing new analysis filled with nuance and depth, which takes a comparative approach to comics from one national context to another. An extraordinary, groundbreaking work that should inspire a global audience of comics scholars.” —Martha B. Kuhlman, coeditor of The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing Is a Way of Thinking

Notă biografică

Katherine Kelp-Stebbins is Assistant Professor and Associate Director of the Comics Studies Program in the Department of English at the University of Oregon.

Extras

The world is being redrawn. Lines that divide places and pages into discrete units likewise articulate relations of proximity and distance. Whether it be where the panel meets the gutter or where two nations rub against each other, a border is a meeting place. Yet, in an age of global pandemic, climate collapse, and massive human displacement, conventional epistemologies of place are in urgent need of new methodologies. Enter comics. This book contends that comics provide alternative mapping tools and methods for reading the world in its mutability. Instead of reading comics for how they bridge cultures and offer seemingly universal meanings, I propose a new methodological practice of reading transnational comics for difference. Reading for difference means not only looking at how comics are successfully translated both within and between national contexts but also examining points of disorientation and disjuncture among source and target texts. This approach, I contend, offers anticolonial, feminist, antiracist literacies that help us redraw the world as a means of reworlding.

How Comics Travel explores the challenges and benefits of thinking through the idea of world comics as objects of analysis and as tools for epistemological intervention. This project reflects a burgeoning interest in framing and defining comics as a global medium. As a testament to such efforts, in 2018 no less an authority than The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel avowed that “at the time of publication, the idea of a world literature for the graphic novel is gaining momentum” (1). What would a world literature for the graphic novel look like? Rather than presuming the givenness of both world literature and world comics, I propose that we draw from long-standing debates in world literary studies to read world comics according to their differences from—as well as similarities to—world literature. As a paradigm, world literature encourages readers to feel connected to other locations and cultures and to ignore the commercial practices that grant them or deny them access to foreign texts. Comics, on the other hand, are acutely indicative of the uneven flows of globalization as well as the fluctuating business of international comics. This book explores how divergent cultures of comics production, translation, reading, and circulation locate readers according to differential frameworks of expectation, understanding, commercial interests, and publishing industries.

The historical context for this book is based in market logics and academic critique. A marked increase in the production of graphic novels—as indicated by the existence of an entire edited Cambridge volume on their history—has led to overlap between spaces of comics and those of text-only books. In the US, literary publishers such as Pantheon and Norton have added many graphic novels to their lists in the last decade, and bookstores have also taken to shelving image-texts alongside text-texts. However, the commercial proximity and shared print form of the book should not conceal the visual, formal, and economic distinctions between comics and literature, especially in a worldly cast. As Michael Allan asserts, world literature “shares in common a normative definition of literature linked to a particular semiotic ideology” (7); that is, world literature assumes both a definite set of objects and a way of engaging them. Without discounting nuanced work that so many of the literary theorists cited in this book undertake to destabilize the boundaries of the literary and to suggest new reading practices, the binary of literacy and illiteracy remains. Comics, often satirized as indicators of illiteracy, are not so cohesive in their anatomy, literacies, or milieu. Putting literary and translation theorists such as Emily Apter, Aamir Mufti, Rebecca Walkowitz, Pheng Cheah, and Rey Chow into conversation with comics theorists such as Thierry Groensteen, Bart Beaty, Rebecca Wanzo, Ann Miller, Hillary Chute, and Frederick Aldama, I argue that global comics both complements and challenges the precepts of world literature along three areas of divergence: translation, form, and print cultures.

How Comics Travel explores the challenges and benefits of thinking through the idea of world comics as objects of analysis and as tools for epistemological intervention. This project reflects a burgeoning interest in framing and defining comics as a global medium. As a testament to such efforts, in 2018 no less an authority than The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel avowed that “at the time of publication, the idea of a world literature for the graphic novel is gaining momentum” (1). What would a world literature for the graphic novel look like? Rather than presuming the givenness of both world literature and world comics, I propose that we draw from long-standing debates in world literary studies to read world comics according to their differences from—as well as similarities to—world literature. As a paradigm, world literature encourages readers to feel connected to other locations and cultures and to ignore the commercial practices that grant them or deny them access to foreign texts. Comics, on the other hand, are acutely indicative of the uneven flows of globalization as well as the fluctuating business of international comics. This book explores how divergent cultures of comics production, translation, reading, and circulation locate readers according to differential frameworks of expectation, understanding, commercial interests, and publishing industries.

The historical context for this book is based in market logics and academic critique. A marked increase in the production of graphic novels—as indicated by the existence of an entire edited Cambridge volume on their history—has led to overlap between spaces of comics and those of text-only books. In the US, literary publishers such as Pantheon and Norton have added many graphic novels to their lists in the last decade, and bookstores have also taken to shelving image-texts alongside text-texts. However, the commercial proximity and shared print form of the book should not conceal the visual, formal, and economic distinctions between comics and literature, especially in a worldly cast. As Michael Allan asserts, world literature “shares in common a normative definition of literature linked to a particular semiotic ideology” (7); that is, world literature assumes both a definite set of objects and a way of engaging them. Without discounting nuanced work that so many of the literary theorists cited in this book undertake to destabilize the boundaries of the literary and to suggest new reading practices, the binary of literacy and illiteracy remains. Comics, often satirized as indicators of illiteracy, are not so cohesive in their anatomy, literacies, or milieu. Putting literary and translation theorists such as Emily Apter, Aamir Mufti, Rebecca Walkowitz, Pheng Cheah, and Rey Chow into conversation with comics theorists such as Thierry Groensteen, Bart Beaty, Rebecca Wanzo, Ann Miller, Hillary Chute, and Frederick Aldama, I argue that global comics both complements and challenges the precepts of world literature along three areas of divergence: translation, form, and print cultures.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction Graphic Positioning Systems

Chapter 1 The Adventures of Three Readers in the World of Tintin

Chapter 2 Graphic Disorientations: Metro and Translation

Chapter 3 Persepolis and the Cultural Currency of the Graphic Novel

Chapter 4 Border Thinking and Decolonial Mapping in Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’s Haida Manga

Chapter 5 Samandal and Translational Transnationalism

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Introduction Graphic Positioning Systems

Chapter 1 The Adventures of Three Readers in the World of Tintin

Chapter 2 Graphic Disorientations: Metro and Translation

Chapter 3 Persepolis and the Cultural Currency of the Graphic Novel

Chapter 4 Border Thinking and Decolonial Mapping in Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’s Haida Manga

Chapter 5 Samandal and Translational Transnationalism

Bibliography

Index

Descriere

Engages with comics as sites of struggle over representation by developing a new methodology of reading for difference in transnational contexts.