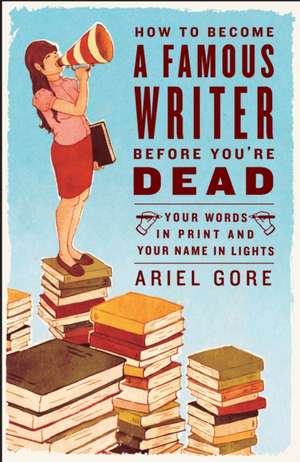

How to Become a Famous Writer Before You're Dead: Your Words in Print and Your Name in Lights

Autor Ariel Goreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2007

If you find yourself writing when you should be sleeping and scribbling notes on odd pieces of paper at every stoplight, you might as well enjoy the fruits of your labor. How to Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead is an irreverent yet practical guide that combines solid writing advice with guerrilla marketing and promotion techniques guaranteed to launch you into print—and into the limelight. You’ll learn how to:

• Reimagine yourself as a buzz-worthy artist and entrepreneur

• Get your work and your name out in the world where other people can read it

• Be an anthology slut and a brazen self-promoter

• Apply real-world advice and experience from lit stars like Dave Barry, Susie Bright, and Dave Eggers to your own career

Cheaper than an M.F.A. but just as informative, How to Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead is your catapult to lit stardom. Just don’t forget to thank Ariel Gore for her inspiring, hands-on plan in the acknowledgments page of your first novel!

Preț: 105.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.21€ • 21.95$ • 16.98£

20.21€ • 21.95$ • 16.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307346483

ISBN-10: 030734648X

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 030734648X

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Ariel Gore is the author of The Hip Mama Survival Guide, The Mother Trip, and Atlas of the Human Heart, as well as the novel The Traveling Death and Resurrection Show. She lives with her family in Portland, Oregon.

Extras

Write

Creativity comes from trust. Trust your instincts. And never hope more than you work.

--Rita Mae Brown

Everybody knows it because Virginia Woolf said it: You need money and a room of your own if you're going to write. But I've written five books, edited three anthologies, published hundreds of articles and short stories, and put out thirty-five issues of my zine without either one. If I'd waited for money and a room, I'd still be an unpublished welfare mom--except they would have cut my welfare off by now. It might be nice to have money and a room (or it might be suicidally depressing--who knows?), but all you really need is a blank page, a pen, and a little bit of time.

Maybe it goes without saying that if you want to become a famous writer before you're dead, you'll have to write something. But the folks in my classes with the biggest ideas and the best publicity shots ready to grace the back covers of their best-selling novels are also usually the ones who aren't holding any paper. They've got plans, lemme tell ya, and their book is going to be better than yours. Too bad it's written entirely on the sheaves of their imagination.

I don't know all the reasons folks pay good money to take my classes and still don't write, but often it has to do with their own high expectations of themselves and wild notions about genius. They think stories should spring fully formed like goddesses from their Zeus-heads. They read novels by masters and imagine their own books snuggling up with the classics at the bookstore. They can't fathom the reality that all these masterpieces were once messy scrawls across ripped pages. First drafts of masterpieces are rarely recognizable as such--and good writers don't leave the price tags on their work. Inspiration comes mythic-magical, but an annoying thing happens in the transmission from inspiration to worldly draft: Things come out a little fuzzy. Introductions are clunky, transitions are awkward, dialogue sounds forced, and sensory details are wholly lacking. A writer's privilege is that she can fix it later. And then fix it again. There's magic in the first raw draft of a story, but the real alchemy happens in rewriting.

It doesn't take a world of discipline to put words to paper--plenty of writers are famously undisciplined procrastinators--but it does take a commitment bordering on obsession, and it takes some humility.

It's Thursday evening and my dreamy student walks in and takes her seat, empty-handed.

"Didn't get a chance to write anything this week?" I ask.

She shakes her head, looks down at her lap. "I didn't have time."

And I nod.

"When do you have time to write?" she asks.

And I answer as honestly as I can: If I'm on deadline, I write furiously. A chapter a day. One of my best writing teachers, Ms. Sarah Pollock back at Mills College, taught me that it isn't the most talented writers who are widely published, but rather the ones who meet their deadlines. So I've always met my deadlines.

Left to my own inspirations, I write in spurts and stops--sometimes every day for hours and sometimes not at all. Weeks pass. I think I'm blocked. What does that mean, "blocked"? I decide I'm empty. With some relief and some nostalgia, I think it's over--this need to put thoughts to words and words to paper. I consider other jobs, like carpentry or bartending. I romanticize more physical hobbies like weight lifting or cooking. I forget all about it. I get distracted. And then one day I wake up from a strange dream of elephants stampeding over bridges and I sit down to a blank page and see what comes of it.

That doesn't answer my student's question, of course. The answer is that I write when I can.

As a teenager, I traveled all over Asia and Europe, almost never enrolled in school, almost never punctuated my days with a regular job. I didn't have much money, so I slept in hostels, squats, train stations, and doorways. I had all the time in the world. Sometimes I sat in near-empty caf*s, bored out of my mind. Aside from a cork-covered journal that took me four years to fill and an hour to burn, I wrote nothing.

I've never been more productive than I was in my early twenties. I had a baby, took a full load of college classes, worked part-time, spent a day out of every week dealing with bureaucracies at the welfare office, the financial aid office, or family court. Still, my daughter's infancy lent an urgency to my days. I wanted to be a writer. Even if I produced nothing publishable or otherwise presentable to the world, I had to write. Something. Every day. Sketches. Observations. Whatever. I wanted to be a writer, so I became one. How? I wrote things down.

Later, when I finished grad school and my daughter started elementary, I wrote every day from nine A.M. to one P.M. Four hours seemed a goodly chunk of time, but I kept to a leisurely pace. No mad-rushing, computer-key-banging, scribbling-across-a-blank-page-just-to-fill-it dash through the night toward the inevitable moment when the baby would wake, hungry and demanding a tit, pulling me away from the kitchen table and into the bedroom we shared, forcing me, finally, to lie down, to feed her, to fall asleep. And dream. Nine A.M. to one P.M.

Then I invited a partner to come and live with us. Nine A.M. to one P.M. But wouldn't it be nicer to go out to breakfast than to write? Wouldn't it be just as well to sit and talk?

I'll write nights, I decided, before I go to bed. Night: The sun sets, painting things orange. My daughter needs help with her homework. She needs to be tucked in. Kiss me good night, Mama. Tell me another story in the dark. At last she's asleep. Or she's not asleep and I leave her with instructions to count porcupines. From the dark of her room to the flickering light of the living room . . . there's a trashy Lifetime movie on TV and we've got some cheap wine. My neck hurts. The chiropractor says it's because I use the wrong muscles to move my arms. Oh, well. Weary eyes, tired of focusing. I've seen this movie before. I take out my contacts and change into my pajamas, jot a few blurry lines across the top of a yellow legal pad. Should I get my glasses? No. Turn out the light, dear. You can write tomorrow.

And so it goes. There are children to be raised, money to be earned, wine to drink, movies to watch, lovers to kiss.

When do I write? I write when I can. I've learned that I work best on deadline, so I invent my own closing dates and trick myself into believing something bad will happen if I don't have, say, twelve pages by Tuesday. I write during the day when my daughter is at school. I write at night when everyone else is sleeping. I write in the morning before they get up. I write in the afternoon when my daughter is on the phone. I bought a blue velvet couch at a garage sale and put it out on the covered porch and it became my office. I've picked up the pace. If I get an hour, I can write five pages. It's nothing Kerouac would have been proud of. Fuck Kerouac.

I write while I'm driving. This is probably rather dangerous. Worse than being on the cell phone, really. But I try to be careful. I write in my head and then I speak it out loud so I won't forget and then I jot it down at red lights.

This is why I do not take the freeway.

I learned to write while driving when my daughter was small and her car seat provided the only respite before sleep. Later she got a plastic car and tooled around our concrete backyard muttering half-lines of poetry as she turned the wheel because she understood that this was how to drive--you mutter and then you write at red lights. I don't even look down at the notebook in my lap as I scribble, because if I do, the person behind me inevitably starts raging on his horn when the light turns green and I don't budge. I keep my eye on the signal, hoping it will stay red just a little bit longer, and I write in a shorthand that's part English, part Chinese, and part random symbolism. Arrows and circles and plus signs and ankhs and a cursive that would make my third-grade penmanship teacher weep serve as my first draft. It's pretty hard to decipher it all when I get home, but I do the best I can.

"But I don't have any time to write," my student says. And I don't ask her how it is, then, that she has time to come to class. I'm glad to have her, even empty-handed. Instead, I offer some suggestions: If you don't have time to write, stop answering the phone. Change your e-mail address. Kill your television. If you don't have a baby, have one. If you have a baby, get a sitter. If you work too much, work more. If you don't work enough, work less. If there's a problem, exaggerate it. If you're broke, go to the food bank. If you have too much money, give it away. If you're north, go south. If you're south, go north. If you don't drink, start. If you drink, sober up. If you're in school, drop out. If you're out of school, drop in. If you believe you have a year to live, imagine you have a hundred. If you believe you have a hundred years to live, imagine you only have one. If you're sane, go crazy. If you're crazy, snap out of it. If you've got a partner, break up. If you're single, find a lover! The shock of the new--shake yourself awake. There is only this moment, this night, this remembrance rolling toward you from the distant past, this blank page, this inspiration yielding itself to you. Will you meet it?

You don't need money and a room of your own, you need pen and paper, and my gift to you now is Marcy Sheiner's most excellent poem, "I Write in the Laundromat."

I write in the Laundromat.

I am a woman

and between wash & dry cycles

I write.

I write while the beans soak

and with children's voices in my ear.

I spell out words for scrabble

while I am writing.

I write as I drive to the office

where I type a man's letters

and when he goes to lunch

I write.

When the kids go out the door

on Saturday I write

and while the frozen dinners thaw

I write.

I write on the toilet

and in the bathtub

and when I appear to be talking

I am often writing.

I write in the Laundromat

while the kids soak

with scrabbled ears

and beans in the office

and frozen toilets

and in the car

between wash and dry.

And your words

and my words

and her words

and their words

and I am a woman

and I write in the Laundromat.

Virginia Woolf had a point with all her talk about money and a room. I catch her drift. We all need a level of emotional and practical autonomy if we're going to write. Within authoritarian relationships, the creative life becomes taboo. But here and now in this millennium, to continue to believe that we need money and a room suggests that the creative life is some kind of luxury we may never be able to afford. I reject that. My experience rejects that. I've noticed that female authors and mothers are the ones most frequently asked how we find time to write. It is assumed that men and folks without kids aren't having to make up excuses about why the dishes aren't done. But this attitude does a disservice to us all. Male or female, responsible for five children and two dogs or just for ourselves, we've all been conditioned, pressured, and bullied into believing that our creative lives are selfish nonsense. We want to be good, so we put creativity at the end of our to-do lists:

Wake up

Shower

Make breakfast

Take kids to school

Walk dogs

Do laundry

Call Dad and tell him I got a real job

Go to work

Write memos: "Enclosed please find

the enclosed enclosure."

Pick up kids

Pay bills

Feed dogs

Watch evening news

Get paranoid

Go to Safeway to buy salad kits and

pre-marinated chicken

Make dinner

Write novel

And then we kick ourselves because the novel isn't written. We look down at our laps and blush when our writing teacher asks us if we got a chance to write this week. Of course we didn't get a chance to write--it was the last thing on our list. We had a glass of wine with dinner. We got sleepy. I'm going to tell you something, and it is something I want you to remember: No one ever does the last thing on their to-do list.

Grab a pen and paper, and if you're going to use them to write a to-do list, make sure you give yourself time to write way up there at the top.

Dream

To build any creative life you need two things: dreams and action. It's true that even if you can visualize in perfect detail a published book, it ain't never going to happen without daily work. But if you can't imagine the life you desire, no amount of squirreling around is going to get you there.

All doing and no dreaming makes Ariel a dull, stressed-out busybody. And so I dream. I imagine, for example, that this book is already done. My imagination doesn't make me lazy (Oh, yeah, I already finished that), but it relieves me of all the stress and struggle about whether it will ever be finished. I imagine it finished. And then I work.

Imagine a few of the things you intend to write in this lifetime. Imagine the stories or the books or the plays. Imagine the process of writing them. Imagine late nights at the computer and sunrise inspirations. Imagine the products of your creation. Imagine the satisfaction of completion. Picture your byline in the magazine, the dog-eared books, the opening night. Close your eyes and see the reader on his couch turning pages. Imagine the audience sitting in the dark. Imagine your book in the library--a bridge beyond time and death.

First there was the word, it says in the Bible.

We are here to create.

But "it takes a heap of loafing to write a book," Gert-rude Stein said.

It's true that planning to write a book is not writing.

Creativity comes from trust. Trust your instincts. And never hope more than you work.

--Rita Mae Brown

Everybody knows it because Virginia Woolf said it: You need money and a room of your own if you're going to write. But I've written five books, edited three anthologies, published hundreds of articles and short stories, and put out thirty-five issues of my zine without either one. If I'd waited for money and a room, I'd still be an unpublished welfare mom--except they would have cut my welfare off by now. It might be nice to have money and a room (or it might be suicidally depressing--who knows?), but all you really need is a blank page, a pen, and a little bit of time.

Maybe it goes without saying that if you want to become a famous writer before you're dead, you'll have to write something. But the folks in my classes with the biggest ideas and the best publicity shots ready to grace the back covers of their best-selling novels are also usually the ones who aren't holding any paper. They've got plans, lemme tell ya, and their book is going to be better than yours. Too bad it's written entirely on the sheaves of their imagination.

I don't know all the reasons folks pay good money to take my classes and still don't write, but often it has to do with their own high expectations of themselves and wild notions about genius. They think stories should spring fully formed like goddesses from their Zeus-heads. They read novels by masters and imagine their own books snuggling up with the classics at the bookstore. They can't fathom the reality that all these masterpieces were once messy scrawls across ripped pages. First drafts of masterpieces are rarely recognizable as such--and good writers don't leave the price tags on their work. Inspiration comes mythic-magical, but an annoying thing happens in the transmission from inspiration to worldly draft: Things come out a little fuzzy. Introductions are clunky, transitions are awkward, dialogue sounds forced, and sensory details are wholly lacking. A writer's privilege is that she can fix it later. And then fix it again. There's magic in the first raw draft of a story, but the real alchemy happens in rewriting.

It doesn't take a world of discipline to put words to paper--plenty of writers are famously undisciplined procrastinators--but it does take a commitment bordering on obsession, and it takes some humility.

It's Thursday evening and my dreamy student walks in and takes her seat, empty-handed.

"Didn't get a chance to write anything this week?" I ask.

She shakes her head, looks down at her lap. "I didn't have time."

And I nod.

"When do you have time to write?" she asks.

And I answer as honestly as I can: If I'm on deadline, I write furiously. A chapter a day. One of my best writing teachers, Ms. Sarah Pollock back at Mills College, taught me that it isn't the most talented writers who are widely published, but rather the ones who meet their deadlines. So I've always met my deadlines.

Left to my own inspirations, I write in spurts and stops--sometimes every day for hours and sometimes not at all. Weeks pass. I think I'm blocked. What does that mean, "blocked"? I decide I'm empty. With some relief and some nostalgia, I think it's over--this need to put thoughts to words and words to paper. I consider other jobs, like carpentry or bartending. I romanticize more physical hobbies like weight lifting or cooking. I forget all about it. I get distracted. And then one day I wake up from a strange dream of elephants stampeding over bridges and I sit down to a blank page and see what comes of it.

That doesn't answer my student's question, of course. The answer is that I write when I can.

As a teenager, I traveled all over Asia and Europe, almost never enrolled in school, almost never punctuated my days with a regular job. I didn't have much money, so I slept in hostels, squats, train stations, and doorways. I had all the time in the world. Sometimes I sat in near-empty caf*s, bored out of my mind. Aside from a cork-covered journal that took me four years to fill and an hour to burn, I wrote nothing.

I've never been more productive than I was in my early twenties. I had a baby, took a full load of college classes, worked part-time, spent a day out of every week dealing with bureaucracies at the welfare office, the financial aid office, or family court. Still, my daughter's infancy lent an urgency to my days. I wanted to be a writer. Even if I produced nothing publishable or otherwise presentable to the world, I had to write. Something. Every day. Sketches. Observations. Whatever. I wanted to be a writer, so I became one. How? I wrote things down.

Later, when I finished grad school and my daughter started elementary, I wrote every day from nine A.M. to one P.M. Four hours seemed a goodly chunk of time, but I kept to a leisurely pace. No mad-rushing, computer-key-banging, scribbling-across-a-blank-page-just-to-fill-it dash through the night toward the inevitable moment when the baby would wake, hungry and demanding a tit, pulling me away from the kitchen table and into the bedroom we shared, forcing me, finally, to lie down, to feed her, to fall asleep. And dream. Nine A.M. to one P.M.

Then I invited a partner to come and live with us. Nine A.M. to one P.M. But wouldn't it be nicer to go out to breakfast than to write? Wouldn't it be just as well to sit and talk?

I'll write nights, I decided, before I go to bed. Night: The sun sets, painting things orange. My daughter needs help with her homework. She needs to be tucked in. Kiss me good night, Mama. Tell me another story in the dark. At last she's asleep. Or she's not asleep and I leave her with instructions to count porcupines. From the dark of her room to the flickering light of the living room . . . there's a trashy Lifetime movie on TV and we've got some cheap wine. My neck hurts. The chiropractor says it's because I use the wrong muscles to move my arms. Oh, well. Weary eyes, tired of focusing. I've seen this movie before. I take out my contacts and change into my pajamas, jot a few blurry lines across the top of a yellow legal pad. Should I get my glasses? No. Turn out the light, dear. You can write tomorrow.

And so it goes. There are children to be raised, money to be earned, wine to drink, movies to watch, lovers to kiss.

When do I write? I write when I can. I've learned that I work best on deadline, so I invent my own closing dates and trick myself into believing something bad will happen if I don't have, say, twelve pages by Tuesday. I write during the day when my daughter is at school. I write at night when everyone else is sleeping. I write in the morning before they get up. I write in the afternoon when my daughter is on the phone. I bought a blue velvet couch at a garage sale and put it out on the covered porch and it became my office. I've picked up the pace. If I get an hour, I can write five pages. It's nothing Kerouac would have been proud of. Fuck Kerouac.

I write while I'm driving. This is probably rather dangerous. Worse than being on the cell phone, really. But I try to be careful. I write in my head and then I speak it out loud so I won't forget and then I jot it down at red lights.

This is why I do not take the freeway.

I learned to write while driving when my daughter was small and her car seat provided the only respite before sleep. Later she got a plastic car and tooled around our concrete backyard muttering half-lines of poetry as she turned the wheel because she understood that this was how to drive--you mutter and then you write at red lights. I don't even look down at the notebook in my lap as I scribble, because if I do, the person behind me inevitably starts raging on his horn when the light turns green and I don't budge. I keep my eye on the signal, hoping it will stay red just a little bit longer, and I write in a shorthand that's part English, part Chinese, and part random symbolism. Arrows and circles and plus signs and ankhs and a cursive that would make my third-grade penmanship teacher weep serve as my first draft. It's pretty hard to decipher it all when I get home, but I do the best I can.

"But I don't have any time to write," my student says. And I don't ask her how it is, then, that she has time to come to class. I'm glad to have her, even empty-handed. Instead, I offer some suggestions: If you don't have time to write, stop answering the phone. Change your e-mail address. Kill your television. If you don't have a baby, have one. If you have a baby, get a sitter. If you work too much, work more. If you don't work enough, work less. If there's a problem, exaggerate it. If you're broke, go to the food bank. If you have too much money, give it away. If you're north, go south. If you're south, go north. If you don't drink, start. If you drink, sober up. If you're in school, drop out. If you're out of school, drop in. If you believe you have a year to live, imagine you have a hundred. If you believe you have a hundred years to live, imagine you only have one. If you're sane, go crazy. If you're crazy, snap out of it. If you've got a partner, break up. If you're single, find a lover! The shock of the new--shake yourself awake. There is only this moment, this night, this remembrance rolling toward you from the distant past, this blank page, this inspiration yielding itself to you. Will you meet it?

You don't need money and a room of your own, you need pen and paper, and my gift to you now is Marcy Sheiner's most excellent poem, "I Write in the Laundromat."

I write in the Laundromat.

I am a woman

and between wash & dry cycles

I write.

I write while the beans soak

and with children's voices in my ear.

I spell out words for scrabble

while I am writing.

I write as I drive to the office

where I type a man's letters

and when he goes to lunch

I write.

When the kids go out the door

on Saturday I write

and while the frozen dinners thaw

I write.

I write on the toilet

and in the bathtub

and when I appear to be talking

I am often writing.

I write in the Laundromat

while the kids soak

with scrabbled ears

and beans in the office

and frozen toilets

and in the car

between wash and dry.

And your words

and my words

and her words

and their words

and I am a woman

and I write in the Laundromat.

Virginia Woolf had a point with all her talk about money and a room. I catch her drift. We all need a level of emotional and practical autonomy if we're going to write. Within authoritarian relationships, the creative life becomes taboo. But here and now in this millennium, to continue to believe that we need money and a room suggests that the creative life is some kind of luxury we may never be able to afford. I reject that. My experience rejects that. I've noticed that female authors and mothers are the ones most frequently asked how we find time to write. It is assumed that men and folks without kids aren't having to make up excuses about why the dishes aren't done. But this attitude does a disservice to us all. Male or female, responsible for five children and two dogs or just for ourselves, we've all been conditioned, pressured, and bullied into believing that our creative lives are selfish nonsense. We want to be good, so we put creativity at the end of our to-do lists:

Wake up

Shower

Make breakfast

Take kids to school

Walk dogs

Do laundry

Call Dad and tell him I got a real job

Go to work

Write memos: "Enclosed please find

the enclosed enclosure."

Pick up kids

Pay bills

Feed dogs

Watch evening news

Get paranoid

Go to Safeway to buy salad kits and

pre-marinated chicken

Make dinner

Write novel

And then we kick ourselves because the novel isn't written. We look down at our laps and blush when our writing teacher asks us if we got a chance to write this week. Of course we didn't get a chance to write--it was the last thing on our list. We had a glass of wine with dinner. We got sleepy. I'm going to tell you something, and it is something I want you to remember: No one ever does the last thing on their to-do list.

Grab a pen and paper, and if you're going to use them to write a to-do list, make sure you give yourself time to write way up there at the top.

Dream

To build any creative life you need two things: dreams and action. It's true that even if you can visualize in perfect detail a published book, it ain't never going to happen without daily work. But if you can't imagine the life you desire, no amount of squirreling around is going to get you there.

All doing and no dreaming makes Ariel a dull, stressed-out busybody. And so I dream. I imagine, for example, that this book is already done. My imagination doesn't make me lazy (Oh, yeah, I already finished that), but it relieves me of all the stress and struggle about whether it will ever be finished. I imagine it finished. And then I work.

Imagine a few of the things you intend to write in this lifetime. Imagine the stories or the books or the plays. Imagine the process of writing them. Imagine late nights at the computer and sunrise inspirations. Imagine the products of your creation. Imagine the satisfaction of completion. Picture your byline in the magazine, the dog-eared books, the opening night. Close your eyes and see the reader on his couch turning pages. Imagine the audience sitting in the dark. Imagine your book in the library--a bridge beyond time and death.

First there was the word, it says in the Bible.

We are here to create.

But "it takes a heap of loafing to write a book," Gert-rude Stein said.

It's true that planning to write a book is not writing.

Descriere

This irreverent and empowering guide helps aspiring writers turn themselves into buzzworthy authors.