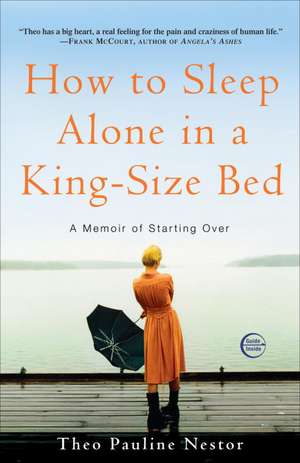

How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed: A Memoir of Starting Over

Autor Theo Pauline Nestoren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2009

Less than an hour after confronting her husband over his massive gambling losses, Theo banishes him from their home forever. With two young daughters to support and her life as a stay-at-home mother at an abrupt end, Nestor finds herself slipping from “middle-class grace” as she attends a court-ordered custody class, stumbles through job interviews, and–much to her surprise–falls in love once again. As Theo rebuilds her life and recovers her sense of self, she’s forced to confront her own family’s legacy of divorce. “I’m from a long line of stock market speculators, artists of unmarketable talents, and alcoholics,” writes Nestor. “The higher, harder road is not our road. We move, we divorce, we drink, or we disappear.”

Nestor’s journey takes her deep into her family’s past, to a tiny village in Mexico, where she discovers the truth about how her sister ended up living in a convent there after their parents divorced in the early sixties. What she learns ultimately brings her closer to understanding her own divorce and its impact on her two daughters. “I knew from experience that for children divorce means half the world is constantly eclipsed. When you’re with one parent, the other must always slip out of view,” Nestor writes.

Funny, openhearted, and brave, How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed will speak to anyone who has passed through the halls of divorce court or risked tenderness after loss. It marks the debut of an enchanting, deeply truthful voice.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 86.21 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 129

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.50€ • 17.64$ • 13.75£

16.50€ • 17.64$ • 13.75£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307346773

ISBN-10: 0307346773

Pagini: 278

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307346773

Pagini: 278

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

THEO PAULINE NESTOR teaches writing at the University of Washington. Her essay “The Chicken’s in the Oven, My Husband’s out the Door” was published in the New York Times “Modern Love” column and was the genesis of this book. She lives in Seattle, Washington, with her two daughters.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Things Fall Apart

Some marriages grind to a halt; two tired people lock down into a final frozen position like the wheels of rusty gears that refuse at last to mesh again. Other marriages, like mine, blow apart midflight, torn asunder by forces larger than themselves, viewers watching numbly as the networks broadcast the final surreal seconds over and over again.

It's late September, a time when Seattle always seems so easy and forgiving, as though you'll forever be padding barefoot out to the garden for a handful of basil and rosemary, as though the skies will never turn gray and close down around you. It's warm still, but past the last hot days of Indian summer. I've waited for this day for at least half the summer--a day cool enough to roast a chicken. When I put our five-pound chicken in the oven, a shower of fresh green herbs clinging to its breast, I am married. As far as I know, nothing is wrong, or at least not really wrong. By the time I pull this chicken out of the oven, I will have asked my husband to leave our house, and he'll have driven away with his green car stuffed with clothes slipping off their hangers.

Last night we went to sleep beside each other as we have for the last twelve years, neither of us knowing it would be for the last time. Could I have seen this coming? I ask myself this now, and I realize that I might have, had I been watching rather than living, had I not been scrambling to and from Jess's preschool and Natalie's science fair and the Children's Theater portrayal of Go, Dog. Go!, had I not been writing and teaching part-time at the university and squeezing in walks around Green Lake with my friends.

But even if I hadn't been busy with all that, I probably wouldn't have sat still, still enough to realize that something was wrong, to say to myself: There's a reason why you feel this way. That nagging feeling that you've misplaced something or that you're working too hard to hold the universe together--that's real. You've felt it before, long ago, when you were too young to know the words for all the ways that life could go wrong. You've gotten too used to that barely audible hum of doubt. And now, here it is again. Quiet. Listen. It's the voice of that part of you that hasn't missed a thing.

At four-thirty, the chicken's in the oven, and I'm waiting for Kevin to return with Natalie from soccer practice. Jessica is sitting at the counter, mashing Play-Doh into patties, while I pace around the kitchen trying to figure out something I'm refusing to see. I have this sinking feeling something is wrong, and it has to do with money. It's odd how I can be obsessed with a problem--scouring bank statements and frantically pawing through bills--yet blind to the real source of the trouble. The thing is, Kevin has been very busy with his real estate business these past few months, but he still hasn't made any real money. It's nothing we haven't seen before in his business--a deal falls apart, a commission is unexpectedly reduced--but this time things just don't add up; the busier he gets, the less money he seems to make. But every time I try to crack the code of where all the money is going, one of the kids asks whether we can go for ice cream or to the park and the facts and numbers slip back into the fuzzy abyss that I've come to consider Kevin's half of our family's concerns.

I decide to call the bank once again to confirm the balance on my checking account. A hundred dollars was withdrawn from a nearby ATM two nights before at midnight. But I know that's impossible--we were all in bed on Sunday at midnight. I remembered we all watched Daddy Day Care in the big bed and had the kids asleep in their bunks by nine. So I cancel the card and ask the nice customer service person to start a fraud report. Then I look again in my wallet. How can the card be in my wallet if someone else used it? Does someone have my bank card number? Is it identity theft? My mother sends me at least one article a week on identity theft, which I promptly recycle, and I've always suspected that my punishment for not reading them would eventually be to have my identity stolen.

At 4:53 I'm staring at the broken red lines of the numbers on the microwave clock when a cold knowledge floods through me like a glacial thawing. I know now that this has to do with Kevin. Sunday night starts to come back to me in patches. I'd gone to sleep right after the kids, but Kevin had gone downstairs to watch TV. Like many nights, I had no idea what time he'd crawled into bed beside me. He's always been a night owl, and lately going to bed at separate times has seemed like a brilliant arrangement, as there's been this constant low-level friction between us. The least little irritating comment by one of us, things we might've shaken off years ago, can ignite a hopeless argument that is simultaneously about nothing and about everything, both shockingly trivial and terrifyingly serious. But in a long marriage, it gets pretty hard to tell what's serious and what's not: what's you, what's the other person, and what's just life. Sometimes we get along really well, and sometimes we don't. The bad stretches are misery, but it's the kind of ordinary misery that you'd expect from any marathon endeavor, the price of togetherness. We came close to breaking up once years ago and weathered that, so I've always assumed that--unless something terrible happens--we'll be married at least until the kids are grown. With two kids still in elementary school, I don't have the presence of mind to fathom what life might look like after their high school graduations. It's like life on other planets; maybe it's there, but you really can't picture it.

But now I know that it was after midnight on Sunday when he came to bed, probably well after. I don't know the details yet, but I feel the enormity of the situation with my whole body.

When they finally arrive, at ten after five, Natalie clomps up the front stairs first in her soccer cleats. She wants to know if she can watch Arthur. As I nod yes to her and she scrambles upstairs, I stare at Kevin. I'm thinking that if I stare hard enough I might be able to see right through him to the secrets he's been keeping, but I can't. A poker face, they call it. He's trained himself to bluff and not show it--at the card table and with me.

"We need to talk," I say in an ominous tone, hoping I can scare a confession out of him. But I've grossly underestimated how long and how deeply he's held this secret, and how determined he is to hang on to it.

We walk back into our daughters' room and I close the door. I sit on the desk chair and he's hunched over on the bottom bunk. Behind him, pensive fairies in gossamer gowns float by on the wallpaper, a persistent promise of security from a world where picking a cabbage rose is the tallest order of the day. Wallpapering the girls' room was the first thing we did four years ago when we bought this hundred-year-old house.

"I think you have something to tell me," I begin.

"No, I don't," he says quickly.

This seems like a strange and suspicious reply. Wouldn't an innocent person say something more like, "What in the hell are you talking about?" I notice that there are very dark circles under his eyes. I realize now that I've seen them before but not registered them, in that peculiar way you can see but not register changes on those faces you know exceedingly well, like your own or the face of the person to whom you've been married for more than a decade.

I confront him with the withdrawal from the bank and he denies knowing anything about it. His face, though, looks ashen and drawn, and suddenly I realize that my hunch is right. I know, too, that there's a lot more to this--more than I want to know.

I know that he remembers what I said to him five years ago, when I opened a credit card bill for $5,000 he'd secretly gambled away. I was pregnant with our younger daughter, Jessica, then, and I told him that was the last time I could endure a break in trust. If it happened again, I said, I would have to get a divorce. To save our marriage and try to rebuild trust, we went to couples therapy and set up new "safety measures": He'd give me his commission checks to keep in a separate account, and he'd call me more often to tell me where he was and when he'd be home.

How did we get to this desolate place? How did I lose this person who once was my closest friend?

I decide to bluff. "The woman at the bank said that when they run the fraud report, they can bring up photos from the ATM. They'll be able to tell who used my card last Sunday at midnight."

He holds his breath for a second and then says, "Okay, so big deal. I took the money from your account."

I look at him, trying to record these new facts: A few nights ago he waited for me to go to sleep, went downstairs, took the bank card from my purse, drove to the bank, entered my PIN, withdrew the hundred dollars, then came home and returned the card to my purse, and went to sleep beside me.

I can't. And I can't believe that this is the person I'm married to. But some part of me knows it's true and knows that there's more bad news ahead. She's the one who says, "You're gambling again."

He admits that he is, but he won't admit the details or how much he's lost. It will be days before I learn that he has charged tens of thousands of dollars we don't have to charge cards I knew nothing about, that the cards are stashed in the glove compartment of his car and the bills sent to another address, and by then he will be holed up in a motel a few miles away, never coming back to live in our house again. In fact, he will be gone before I even have time to absorb what has happened, even before the juice from the thigh of the chicken "no longer runs pink," to quote one of my favorite cookbooks.

At 6:00 p.m., with the September sun on the wane, the roasted chicken--burnt rosemary stems like black twigs now scoring the breast--sits neglected on the counter. The chicken feeds only one person that night--our nine-year-old daughter, Natalie. I'm not hungry anymore. In fact, the chicken looks strangely unfamiliar, a dinner dropped into my kitchen by aliens perhaps.

Our five-year-old daughter, Jessie, says she won't eat a chicken that looks like a chicken, but would possibly eat five chicken nuggets from the box in the freezer. For once, I don't argue, "But all this good food is going to waste." The waste has already happened. I take the red box from the freezer, pluck out five tawny nuggets and place them on a plate, heat them for forty-seven seconds in the microwave, and set them with a fork and napkin in front of Jessie, who believes that her father has gone to meet a friend downtown and that the two of them will be leaving tonight on an impromptu car trip. It is a ludicrous story. A last-minute trip with a friend who lives two thousand miles away but has, apparently, just arrived downtown unexpectedly? Yet the children believe me, and I hate myself a little already. "Dad will come home in a week," I tell them. But I know he won't. He won't ever come home.

How did you lose your husband? I ask myself.

At first slowly and then all at once.

2

The Girl and Her Mother

One of the first calls I make is to my mother. I call her before I can talk myself out of it, punch in her numbers so quickly and so instinctively that I'm a little startled when she actually answers.

I tell her something is horribly wrong but the children are okay.

"What is it?" she asks, and I can feel her holding her breath and I know--because I am also a mother--how afraid she is of what will come next.

"We're getting divorced," I say. The word comes out long and mangled, a high-pitched animal sound.

"Are you sure?" she asks.

I say I am.

"Okay, then," she says. "You're going to be okay, dear. You really will be."

I'm surprised to find myself believing this the way a child believes her mother when she tells her the skinned knee will heal or that she'll someday forget about the boy who turned her down. I wait for her to talk me out of it, to say maybe things can be worked out, or the dreaded refrain of "men will be men," but she doesn't, and my relief is instant. She just takes me at my word. If I say it's over, then it must be.

In some ways it's as if we're on equal footing at last. Marriage on the rocks--this is her territory, and her role has transformed in the last two minutes from outsider to guide, a role neither of us thought she'd fill again for me. But the change isn't just in her; in the instant that I know she has heard and accepted my decision, I feel something shift in me. It's as though tectonic plates are converging, and a new landscape, as yet imperceptible, has begun forming. Ten million years might pass before there's a mountain range here, but deep below ground the earth changes irrevocably each time continents collide. And some part of me has begun to trust my mother to help me.

My graduate school and professional days behind me--and now my life as a married woman as well--I'm finally about to enter into the kind of life my mother can understand. It makes sense that the daughter's life should look like the mother's, that the daughter has not outstripped her mother. I may not like it, but there's a primal logic to it. By the time my mom was my age--forty-two--she had three kids and was on the verge of her third marriage, which would eventually end, like the others, in divorce. She knows what it's like to pay the bills alone, go to bed alone, and get up in the night alone to feed the baby. She knows what it's like to watch things fall apart.

From the Hardcover edition.

Things Fall Apart

Some marriages grind to a halt; two tired people lock down into a final frozen position like the wheels of rusty gears that refuse at last to mesh again. Other marriages, like mine, blow apart midflight, torn asunder by forces larger than themselves, viewers watching numbly as the networks broadcast the final surreal seconds over and over again.

It's late September, a time when Seattle always seems so easy and forgiving, as though you'll forever be padding barefoot out to the garden for a handful of basil and rosemary, as though the skies will never turn gray and close down around you. It's warm still, but past the last hot days of Indian summer. I've waited for this day for at least half the summer--a day cool enough to roast a chicken. When I put our five-pound chicken in the oven, a shower of fresh green herbs clinging to its breast, I am married. As far as I know, nothing is wrong, or at least not really wrong. By the time I pull this chicken out of the oven, I will have asked my husband to leave our house, and he'll have driven away with his green car stuffed with clothes slipping off their hangers.

Last night we went to sleep beside each other as we have for the last twelve years, neither of us knowing it would be for the last time. Could I have seen this coming? I ask myself this now, and I realize that I might have, had I been watching rather than living, had I not been scrambling to and from Jess's preschool and Natalie's science fair and the Children's Theater portrayal of Go, Dog. Go!, had I not been writing and teaching part-time at the university and squeezing in walks around Green Lake with my friends.

But even if I hadn't been busy with all that, I probably wouldn't have sat still, still enough to realize that something was wrong, to say to myself: There's a reason why you feel this way. That nagging feeling that you've misplaced something or that you're working too hard to hold the universe together--that's real. You've felt it before, long ago, when you were too young to know the words for all the ways that life could go wrong. You've gotten too used to that barely audible hum of doubt. And now, here it is again. Quiet. Listen. It's the voice of that part of you that hasn't missed a thing.

At four-thirty, the chicken's in the oven, and I'm waiting for Kevin to return with Natalie from soccer practice. Jessica is sitting at the counter, mashing Play-Doh into patties, while I pace around the kitchen trying to figure out something I'm refusing to see. I have this sinking feeling something is wrong, and it has to do with money. It's odd how I can be obsessed with a problem--scouring bank statements and frantically pawing through bills--yet blind to the real source of the trouble. The thing is, Kevin has been very busy with his real estate business these past few months, but he still hasn't made any real money. It's nothing we haven't seen before in his business--a deal falls apart, a commission is unexpectedly reduced--but this time things just don't add up; the busier he gets, the less money he seems to make. But every time I try to crack the code of where all the money is going, one of the kids asks whether we can go for ice cream or to the park and the facts and numbers slip back into the fuzzy abyss that I've come to consider Kevin's half of our family's concerns.

I decide to call the bank once again to confirm the balance on my checking account. A hundred dollars was withdrawn from a nearby ATM two nights before at midnight. But I know that's impossible--we were all in bed on Sunday at midnight. I remembered we all watched Daddy Day Care in the big bed and had the kids asleep in their bunks by nine. So I cancel the card and ask the nice customer service person to start a fraud report. Then I look again in my wallet. How can the card be in my wallet if someone else used it? Does someone have my bank card number? Is it identity theft? My mother sends me at least one article a week on identity theft, which I promptly recycle, and I've always suspected that my punishment for not reading them would eventually be to have my identity stolen.

At 4:53 I'm staring at the broken red lines of the numbers on the microwave clock when a cold knowledge floods through me like a glacial thawing. I know now that this has to do with Kevin. Sunday night starts to come back to me in patches. I'd gone to sleep right after the kids, but Kevin had gone downstairs to watch TV. Like many nights, I had no idea what time he'd crawled into bed beside me. He's always been a night owl, and lately going to bed at separate times has seemed like a brilliant arrangement, as there's been this constant low-level friction between us. The least little irritating comment by one of us, things we might've shaken off years ago, can ignite a hopeless argument that is simultaneously about nothing and about everything, both shockingly trivial and terrifyingly serious. But in a long marriage, it gets pretty hard to tell what's serious and what's not: what's you, what's the other person, and what's just life. Sometimes we get along really well, and sometimes we don't. The bad stretches are misery, but it's the kind of ordinary misery that you'd expect from any marathon endeavor, the price of togetherness. We came close to breaking up once years ago and weathered that, so I've always assumed that--unless something terrible happens--we'll be married at least until the kids are grown. With two kids still in elementary school, I don't have the presence of mind to fathom what life might look like after their high school graduations. It's like life on other planets; maybe it's there, but you really can't picture it.

But now I know that it was after midnight on Sunday when he came to bed, probably well after. I don't know the details yet, but I feel the enormity of the situation with my whole body.

When they finally arrive, at ten after five, Natalie clomps up the front stairs first in her soccer cleats. She wants to know if she can watch Arthur. As I nod yes to her and she scrambles upstairs, I stare at Kevin. I'm thinking that if I stare hard enough I might be able to see right through him to the secrets he's been keeping, but I can't. A poker face, they call it. He's trained himself to bluff and not show it--at the card table and with me.

"We need to talk," I say in an ominous tone, hoping I can scare a confession out of him. But I've grossly underestimated how long and how deeply he's held this secret, and how determined he is to hang on to it.

We walk back into our daughters' room and I close the door. I sit on the desk chair and he's hunched over on the bottom bunk. Behind him, pensive fairies in gossamer gowns float by on the wallpaper, a persistent promise of security from a world where picking a cabbage rose is the tallest order of the day. Wallpapering the girls' room was the first thing we did four years ago when we bought this hundred-year-old house.

"I think you have something to tell me," I begin.

"No, I don't," he says quickly.

This seems like a strange and suspicious reply. Wouldn't an innocent person say something more like, "What in the hell are you talking about?" I notice that there are very dark circles under his eyes. I realize now that I've seen them before but not registered them, in that peculiar way you can see but not register changes on those faces you know exceedingly well, like your own or the face of the person to whom you've been married for more than a decade.

I confront him with the withdrawal from the bank and he denies knowing anything about it. His face, though, looks ashen and drawn, and suddenly I realize that my hunch is right. I know, too, that there's a lot more to this--more than I want to know.

I know that he remembers what I said to him five years ago, when I opened a credit card bill for $5,000 he'd secretly gambled away. I was pregnant with our younger daughter, Jessica, then, and I told him that was the last time I could endure a break in trust. If it happened again, I said, I would have to get a divorce. To save our marriage and try to rebuild trust, we went to couples therapy and set up new "safety measures": He'd give me his commission checks to keep in a separate account, and he'd call me more often to tell me where he was and when he'd be home.

How did we get to this desolate place? How did I lose this person who once was my closest friend?

I decide to bluff. "The woman at the bank said that when they run the fraud report, they can bring up photos from the ATM. They'll be able to tell who used my card last Sunday at midnight."

He holds his breath for a second and then says, "Okay, so big deal. I took the money from your account."

I look at him, trying to record these new facts: A few nights ago he waited for me to go to sleep, went downstairs, took the bank card from my purse, drove to the bank, entered my PIN, withdrew the hundred dollars, then came home and returned the card to my purse, and went to sleep beside me.

I can't. And I can't believe that this is the person I'm married to. But some part of me knows it's true and knows that there's more bad news ahead. She's the one who says, "You're gambling again."

He admits that he is, but he won't admit the details or how much he's lost. It will be days before I learn that he has charged tens of thousands of dollars we don't have to charge cards I knew nothing about, that the cards are stashed in the glove compartment of his car and the bills sent to another address, and by then he will be holed up in a motel a few miles away, never coming back to live in our house again. In fact, he will be gone before I even have time to absorb what has happened, even before the juice from the thigh of the chicken "no longer runs pink," to quote one of my favorite cookbooks.

At 6:00 p.m., with the September sun on the wane, the roasted chicken--burnt rosemary stems like black twigs now scoring the breast--sits neglected on the counter. The chicken feeds only one person that night--our nine-year-old daughter, Natalie. I'm not hungry anymore. In fact, the chicken looks strangely unfamiliar, a dinner dropped into my kitchen by aliens perhaps.

Our five-year-old daughter, Jessie, says she won't eat a chicken that looks like a chicken, but would possibly eat five chicken nuggets from the box in the freezer. For once, I don't argue, "But all this good food is going to waste." The waste has already happened. I take the red box from the freezer, pluck out five tawny nuggets and place them on a plate, heat them for forty-seven seconds in the microwave, and set them with a fork and napkin in front of Jessie, who believes that her father has gone to meet a friend downtown and that the two of them will be leaving tonight on an impromptu car trip. It is a ludicrous story. A last-minute trip with a friend who lives two thousand miles away but has, apparently, just arrived downtown unexpectedly? Yet the children believe me, and I hate myself a little already. "Dad will come home in a week," I tell them. But I know he won't. He won't ever come home.

How did you lose your husband? I ask myself.

At first slowly and then all at once.

2

The Girl and Her Mother

One of the first calls I make is to my mother. I call her before I can talk myself out of it, punch in her numbers so quickly and so instinctively that I'm a little startled when she actually answers.

I tell her something is horribly wrong but the children are okay.

"What is it?" she asks, and I can feel her holding her breath and I know--because I am also a mother--how afraid she is of what will come next.

"We're getting divorced," I say. The word comes out long and mangled, a high-pitched animal sound.

"Are you sure?" she asks.

I say I am.

"Okay, then," she says. "You're going to be okay, dear. You really will be."

I'm surprised to find myself believing this the way a child believes her mother when she tells her the skinned knee will heal or that she'll someday forget about the boy who turned her down. I wait for her to talk me out of it, to say maybe things can be worked out, or the dreaded refrain of "men will be men," but she doesn't, and my relief is instant. She just takes me at my word. If I say it's over, then it must be.

In some ways it's as if we're on equal footing at last. Marriage on the rocks--this is her territory, and her role has transformed in the last two minutes from outsider to guide, a role neither of us thought she'd fill again for me. But the change isn't just in her; in the instant that I know she has heard and accepted my decision, I feel something shift in me. It's as though tectonic plates are converging, and a new landscape, as yet imperceptible, has begun forming. Ten million years might pass before there's a mountain range here, but deep below ground the earth changes irrevocably each time continents collide. And some part of me has begun to trust my mother to help me.

My graduate school and professional days behind me--and now my life as a married woman as well--I'm finally about to enter into the kind of life my mother can understand. It makes sense that the daughter's life should look like the mother's, that the daughter has not outstripped her mother. I may not like it, but there's a primal logic to it. By the time my mom was my age--forty-two--she had three kids and was on the verge of her third marriage, which would eventually end, like the others, in divorce. She knows what it's like to pay the bills alone, go to bed alone, and get up in the night alone to feed the baby. She knows what it's like to watch things fall apart.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Theo has a big heart, a real feeling for the pain and craziness of human life."

—Frank McCourt, author of Angela's Ashes

“Theo Nestor has an uncommon ability to evoke common yet very intense emotions. How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed is smart, astringent, funny, precise, candid, and possesses not an ounce of self-pity.”

—David Shields, author of The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead

“Heartbreakingly honest, wryly funny, and revelatory . . . [Nestor’s] clever and relatable prose makes her tale endearing and insightful, and she sidesteps the clichés of a woman wounded with bittersweet honesty.”

—LadiesHomeJournal.com

“A divorced mother’s funny, chatty, revealing take on Splitsville–with just enough anguish and sadness to be utterly believable...An unexpected treat here is a vivid portrait of the author's thrice-married, utterly nonmaternal but generous mother...Women going through the pain and turmoil of separation and divorce will appreciate Nestor’s candor and wit. Not another slick how-to, but a comforting reminder that life goes on after the spouse is gone.” —Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.

—Frank McCourt, author of Angela's Ashes

“Theo Nestor has an uncommon ability to evoke common yet very intense emotions. How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed is smart, astringent, funny, precise, candid, and possesses not an ounce of self-pity.”

—David Shields, author of The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead

“Heartbreakingly honest, wryly funny, and revelatory . . . [Nestor’s] clever and relatable prose makes her tale endearing and insightful, and she sidesteps the clichés of a woman wounded with bittersweet honesty.”

—LadiesHomeJournal.com

“A divorced mother’s funny, chatty, revealing take on Splitsville–with just enough anguish and sadness to be utterly believable...An unexpected treat here is a vivid portrait of the author's thrice-married, utterly nonmaternal but generous mother...Women going through the pain and turmoil of separation and divorce will appreciate Nestor’s candor and wit. Not another slick how-to, but a comforting reminder that life goes on after the spouse is gone.” —Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.