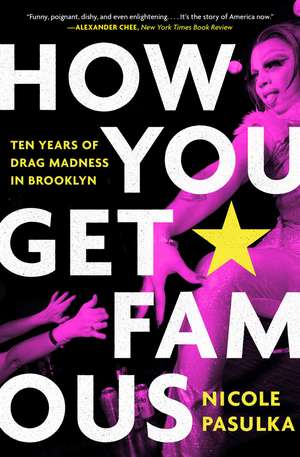

How You Get Famous: Ten Years of Drag Madness in Brooklyn

Autor Nicole Pasulkaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 iul 2023

In How You Get Famous, journalist Nicole Pasulka raucously documents the rebirth of the New York drag scene, following a group of iconoclastic performers with undeniable charisma, talent, and a hell of a lot to prove. In the past decade, drag has become a place where edgy, competitive showoffs can find security in a callous and over priced city, a shot at real money, and a level of recognition queer people rarely achieve. But can drag keep its edge as it travels from the backroom to the main stage?

A “joyful and scrappy” (Esquire) portrait of the 21st-century search for celebrity and community, How You Get Famous is “dripping in plush detail and drama” (Mother Jones) and “stitched together with great respect and love” (The Guardian). It’s the story of an aimless coat check worker who sweet-talked his way into hosting a drag show at a Brooklyn dive bar, a pair of teenagers sneaking into clubs and pocketing tips to help support their families, and eclectic performers who have managed to land a spot on TV and millions of followers…all colliding in an unprecedented account of a subculture on the brink of becoming a cultural phenomenon.

“If you like to have a good time, you want to read this book!”—BuzzFeed

Preț: 103.48 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.80€ • 20.46$ • 16.48£

19.80€ • 20.46$ • 16.48£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Livrare express 18-22 februarie pentru 37.97 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982115807

ISBN-10: 1982115807

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 8-page 4-C Insert

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982115807

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 8-page 4-C Insert

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Nicole Pasulka writes about gender, activism, and criminal justice for publications such as New York magazine, Harper’s Magazine, Mother Jones, VICE, and The Believer. The recipient of numerous prestigious fellowships, her writing has been anthologized in the Best American series and featured on NPR’s All Things Considered. How You Get Famous is her first book.

Extras

Chapter One: Welcome to New York City

“Don’t you fall,” Aja warned, rushing Esai Andino toward the J train, their high heels scraping along the pavement. Putting Esai in the shoes had been a risk. Even in sneakers, the fourteen-year-old boy tripped—over curbs, steps, nothing at all—pretty much every day. The fat cans of Four Loko they’d polished off while getting ready in Aja’s room hadn’t helped Esai’s composure. As soon as their makeup was dry, seventeen-year-old Aja had rushed Esai out the door and into the cold night: two Brooklyn teenagers in search of attention, cash, and adventure in the big city.

Then the pair turned a corner and, sure enough, Esai’s ankle rolled. He screeched and keeled over. Fall 2011 had been mild, but in the evening chill his breath was visible in small puffs. Esai leaned on Aja as they hobbled into the station and up the stairs.

It was their first night out in Manhattan as drag queens. Their first night trying the thing they’d been talking about for months. Earlier that day, Aja had earned fifteen dollars reading a woman’s tarot cards and used the money to buy Esai a pair of gold sparkly heels. Esai paced on the train platform, shivering and limping slightly. He had on black tights and a star-print skirt over a polka-dot bathing suit. Aja, who had been raised as a boy but prefers the pronouns “she” or “they,” was wearing a floral shirt she’d made for a class project at the High School of Fashion Industries.

They arrived at Bar-Tini on Tenth Avenue in Hell’s Kitchen early, to avoid getting carded. A drag queen named Holly Dae, who’d recently changed her name from Holly Caust, was hosting a competition for newcomers called Beat That Face! In the drag world, “beat” could be a noun or a verb meaning a face of makeup or the act of applying makeup. Esai had chosen a drag name: Naya Kimora, because he loved Kimora Lee Simmons, the fashion designer and former wife of hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons. Aja’s name came from the chorus of a catchy Bollywood song. The other queens there had on long dresses and shiny, blond, expensive-looking wigs. Aja and Esai should have felt out of place—conspicuously underage and unpolished—but alcohol had steadied their nerves.

The bar filled up. When it was Esai’s turn to perform, he collected himself at the center of the stage and waited for the DJ to cue his music. The drums began, and Esai started swinging his hips, turning slowly in a circle.

Esai lip-synched as JLo sang, “Let all the heat pour doooown.”

The shoes chewed into Esai’s feet. The beat hit. He ignored the throbbing in his ankle, kicked his leg in front of him, pivoted, and began to twerk. People in the room tittered and politely cheered.

“Dance for your man,” JLo commanded. “Put your hands up in the air-air-air—whoa oh-oh-oh,” she sang. It was a good thing the words were simple, because he had not practiced. Esai left the stage panting and joined Aja, who had performed “Judas” by Lady Gaga, a song about toxic love, with dark synths and a wailing chorus.

Brave and foolish, these two New York City children had done something many older, wiser, and more experienced queers would never dare attempt. They’d gotten into drag, walked into a bar, and jumped onstage, without hesitation and with very little concern for the consequences. They were new, and they were rough around the edges, but even in this utterly amateur moment they had the priceless combination of guts and hunger that helped seemingly small people do big, scary things. Kicking and twirling while lip-synching in front of an audience felt like flying.

Aja lived with her mom on Hopkins and Throop in Brooklyn, where hipster Williamsburg met working-class Bushwick. She was adopted and her father had moved out when she was young. “I was wild,” she would later say about her childhood. At seven, she ran away from the babysitter, and when the police found her on the playground, Aja lied and told the cops her mother had left her there. Later, when Aja locked the door to her bedroom, her mom kicked it in. As a teenager, she dyed the family pug, Gizmo, blue with a spray bottle full of Kool-Aid and once threw an ice cube into a deep fryer in a manic desire to see what would happen. What happened was third-degree burns on her face that healed into bumpy pink scars.

People were always coming for Aja over her scars, her asthmatic wheezing, her swishy walk. Even old ladies on the street would offer unsolicited recommendations for clearer skin. “It’s not acne,” Aja would try to explain, and then sigh, “Oh, never mind.” But Aja could give as good as she got. Bigger boys threw punches and skateboards, Aja threw them back.

Aja was a pariah but talented. By twelve she was hanging out on the East River piers, where queer kids from across the borough gathered to listen to music, trade insults, and dance. Aja was a natural, quickly learning to vogue, kick, and duck-walk as the other kids cheered her on. When Aja wasn’t running the streets, she’d stay up all night perfecting sketches of Pokémon and Mortal Kombat characters. She could read a bitch to tears.

Aja met Esai, whose family occupied a crowded one-bedroom apartment a few blocks away, about a year before that first night out in drag. All the gay boys from the neighborhood crossed paths eventually. At the time, Esai was dating Timothy, a kid Aja knew from Fashion Industries. It wasn’t really Aja’s business, but she liked Esai and she couldn’t stand the thought of him going out with someone with a boxy face, bad skin, and terrible breath. When Timothy heard Aja had been talking shit and threatened to fight her, Aja’s response was a cool “Bitch, you’re nothing more than gum on the street to me.” Aja was not faking. Anyone who’d spent sixteen years disobeying a no-bullshit, always-yelling Puerto Rican mother wouldn’t be scared of much either.

After a few months, Aja’s dogged campaign against Timothy paid off. Esai showed up at Aja’s house to talk about his “boy troubles” (some kid had sent Esai a Facebook message saying he’d been sleeping with Timothy, too) and they bonded over their disgust for Esai’s—now ex—boyfriend. Aja felt protective of Esai. No one seemed to be looking out for him. Some of his close family members were moody and unpredictable—raging one day and sulking the next. Others were like ghosts in the house; the only signs of life were the liquor bottles they hid in the couches and cabinets. Esai’s grandmother, who was from the Dominican Republic, tried to look out for him as best she could, but Esai, feminine and quiet, was basically on his own. Before he was old enough to grow facial hair, he was taking the train to gay house parties in the Bronx where he’d lie about his age and guzzle alcohol. Esai and Aja started hooking up. They’d both been with guys before, but this felt different. Aja wasn’t used to being with someone so young. She thought she could help Esai avoid some of the struggle and drama she’d gone through.

For a while, they were a good match. While Aja sometimes tried to butch up, Esai never hid his girlishness. “I did not give a shit what anyone had to say,” Esai later said about those early years. Ever since he was a little boy, he loved lip gloss and short shorts. His mother would buy him oversized pants and, by the time he was twelve, he was having friends with sewing machines tailor them to show off his ass and thighs. He wondered if he liked rainbows and sparkly clothes because he was actually a woman. In seventh grade, he asked a gynecologist about a prescription for female hormones. The doctor referred him to a therapist. Esai later said this was how he figured out that, no, he wasn’t a woman, he just “wanted to look so soft and cunt” and, to him, that meant manicured nails, crop tops, and a big rhinestone Victoria’s Secret bag.

As a kid, Aja would sometimes steal her cousin’s skirt and line her lips in dark red to do a furious impression of the crass, no-nonsense former supermodel and America’s Next Top Model judge Janice Dickinson falling down the stairs. Aja loved people like Janice Dickinson and Tiffany Pollard, who were fun to watch on TV. “I was always very thoroughly entertained by people who just didn’t really give a fuck,” she later said. The impression had her family howling with laughter and Aja basked in the attention. But it wasn’t until 2011, after Aja and Esai had been hanging out for about six months, that she began to consider calling herself a drag queen. One of the trans girls at the piers told Aja that drag queens made money giving lip sync shows at gay bars in Manhattan. Aja and Esai had both heard of drag queens—men who dressed up as women and performed songs onstage—but they had never really paid them much attention. Now, Aja was intrigued. Money was always tight at home, but it had gotten especially so lately. A few years before, bullies had broken Aja’s arm, and her mom had stayed with her in the hospital, missing so much work she lost her job. They lived close to the poverty line, but what set them apart from many other families in the neighborhood was the fact that Aja’s mom owned her house. It was the foundation of their security and their relationship, the thing that protected them when Aja’s dad left. After her mom lost her job she couldn’t afford her storage space, and so she moved what felt like fifty Tupperware containers full of holiday decorations and old clothes into the house. These hoarding tendencies, her mom’s refusal to throw away something she’d paid money for, had caught up with them and, just as they were at their poorest, they were surrounded by stuff. At one point, Aja came home to find that the lights had been shut off. On another occasion, she and her mom had to make an order of pork fried rice and chicken wings last for several days. Her mother made it clear that once Aja was eighteen she was going to have to support herself. Feeling overwhelmed and powerless, Aja messaged strangers on the internet, chased bullies in city parks, danced with friends at the piers, while, thanks to what Aja thought of as “the grace of higher energies,” her mom managed to hold on to her house. Esai had started crashing with them more regularly, and Aja was desperate to bring in some cash, but hated the idea of a normal job. While voguing had originated in the queer ballroom scene, where kids of color found community and solace competing in categories like “face,” “realness,” and “body,” being a drag queen meant entertaining other gays in bars and nightclubs. Those ballroom queens who ventured into the drag world found they could make real money with their fierce attitude and dance skills, but they were expected to dress accordingly—wigs, makeup, and stylish looks that sold the fantasy of a diva, tough girl, or pop princess. Drag required an outsized alter ego that had the power to make an audience laugh, cry, or get excited—that made them feel something. Drag in bars, as Aja and Esai would learn, existed at the intersection of commerce and art and consisted of doing things Aja loved—lip-synching, dancing, looking cute—but for money. It sounded too good to be true.

Esai was already used to wearing girls’ clothes, so it made sense to dress him up, too. Though Esai was more naturally feminine on the streets, Aja was the one who knew how to paint to look really female. Posing for photos outside the house, Esai looked like a girl on her way to church: button-down floral shirt, pleated skirt, white tights. Esai didn’t have any money for makeup, and no way was he going to ask his father to buy him some, so he mopped it from a local Rite Aid. Aja showed him how to use the stolen foundation and concealer, then they snuck into Aja’s brother’s house to borrow her sister-in-law’s tiny skirts and dresses.

In the regular world, full of tired, yelling, frustrated people, Aja was treated like a nuisance, a person to be controlled or ignored. But dressed up in drag, Aja felt like someone else entirely. She felt special, not because of scars, or a lisp, or asthma, but because she was fabulous, glamorous, or shocking. In drag, Aja was strong and beautiful in ways she hadn’t thought a boy could be. For the first time ever, Aja didn’t want to hide. She wanted to be out in the world. This was a superhero cape complete with mystical powers. The teens hosted a drag show in Aja’s living room. Fifty kids whooped, hollered, and jumped on the furniture as they lip-synched with abandon. Eager to test the moneymaking potential of this fabulous new persona, Aja scoured Facebook looking for drag shows and parties at Manhattan gay bars. For Esai, drag had become his escape from the gloomy atmosphere of his grandmother’s house. He was happiest, in his words, “all pumped and perused,” dressed up like a stylish woman. He wasn’t going to be left behind. He asked Aja—the only other person he knew who did drag—to be his drag mother and take him out. Aja took to the role; it felt natural to be in charge.

In the fall of 2011, hours before their first Manhattan performances, they’d sat in Aja’s bedroom, chugging their Four Lokos while Aja painted Esai’s face and noticed that the gap between the younger boy’s two front teeth made him look even more girlish.

After their performances, Holly, the host at Bar-Tini, called all the contestants up for the judging. Aja and Esai bounded onto the stage and stood next to the other competitors. All the others were aiming for what they called “fishiness,” an arguably disparaging term that describes passable femininity—looking, moving, and talking like a woman. It reminded Esai of what he’d heard about drag pageants, where queens competed in categories like “evening gown,” “swimsuit,” and “talent,” and the crown went to the most poised and put-together queen.

Despite Aja’s efforts, Esai’s makeup was thick and cracked. Their chins were square and reddish, like the shape and texture of a brick. “Grawlick chinnula” was how Esai and Aja sometimes insulted each other when their faces looked particularly busted. They were dressed in polyester skirts that covered too much of their legs and looked much more like schoolgirls than superstars.

None of this was lost on the judges.

“I loved your energy,” said one judge. “But your outfit. Oooh, girl.”

“Your performance was good,” said another. “But you look…” She trailed off.

“You look just horrible,” said a third.

Aja understood that they were long shots—it was their first time out, after all—but she hadn’t been prepared to fail so spectacularly. She’d tried to create the illusion of a flat crotch with duct tape, what’s known as “tucking.” During the judging, the other queens made sure to point out that the silver of the tape was visible. Embarrassed by the reception and annoyed with themselves for giving a fuck, Esai and Aja left the club and jumped the turnstile for a silent ride back to Brooklyn.

Aja would later describe that night as both the beginning of her drag career and a continuation of all her troubles. Yet another sign that, no matter how hard she tried, no matter what she did, people would never accept her and would always stand in her way.

Aja and Esai, like so many Brooklyn drag performers who got their start during the second decade of the twenty-first century, were striving to make money as artists during an unprecedented moment in gay culture. A cadre of drag performers that included Thorgy Thor, Merrie Cherry, Horrorchata, Switch n’ Play, and Sasha Velour—would be the engine of this influential and innovative scene. Drag had long brought queer people moments of acceptance and rejection, but now it would also confer respect and visibility in the wider world. What Aja sensed back in 2011, before she was old enough to vote or even drive a car in New York State, was the growing power and influence of gay people—especially gay people in New York City—to make a performer’s dreams come true.

Not that these opportunities would be equally—or fairly—distributed. Any truly ambitious performer had a rough road to stardom.… Years later, recounting her defeat at the Manhattan show, Aja was still bitter. As her emotions got hotter, her voice grew raspier and her Brooklyn accent thicker. “These bitches never made it easy for me,” she would gripe, and Esai would laugh.

“Girl, your face was a brick,” he said. “We looked horrible.”

A stage is a stage, no matter how small. For as long as there have been gay bars, there have been people who elbowed their way to the front of the room to find self-esteem, confidence, and opportunity by dancing, singing a song, or telling some jokes. If they were good, they became figureheads of the scene. From Alabama to Alaska, these performers brought glamour, excitement, and entertainment to the often maligned or ignored subcultures that formed in tiny rooms and dingy queer bars. On those nights when they were the flashiest creatures in the room, they found a certain type of fame among a crowd that hadn’t yet been represented on Broadway stages, television, or in Hollywood. If they cultivated an alluring personality, gave good shows, and put the time in, they were recognized and respected by the network of friends, lovers, and acquaintances who made up the gay world in their particular city or town. Fame doesn’t always mean your face on a Times Square billboard; it can just as easily be friends of friends you’ve never met, whose names you do not know, telling stories about your exploits and adventures. Unnoticed by the wider world, the gay community had quietly been forging stars like this for generations. Now, it was about to mint a few more.

On a chilly November evening in 2011, Jason Daniels was nursing a beer at Metropolitan in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood when one of the owners mentioned they needed someone to work coat check over the winter. Jason perked up. He had moved to New York City two years earlier from Berkeley, California, with two suitcases and three months of rent money, hoping to be somebody. He wasn’t sure who, exactly, but somebody. Now, at twenty-eight years old, he found himself wasting his days in a windowless office, entering numbers into spreadsheets for a nonprofit alongside an overbearing boss and a bunch of uptight coworkers. He was living like a nobody in the most important place on earth, paying too much rent for too little space on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Even while people partied, screwed, and got rich all around him, Jason was friendless, bored, and broke. It sucked. Coat check seemed a step up, however small, plus he could use the money.

In Berkeley, he’d been raised mostly by his grandmother Ruth, who knew he liked boys but rarely talked about it. An only child, Jason spent a lot of time alone imagining a world where people wanted to get to know him. In these fantasies, he lived on Long Island—a place he’d heard about on TV—and belonged to the wealthiest Black family in the world. Everyone was fascinated by his rich, stylish parents, and all of Jason’s friends were rich and stylish, too. Jason imagined that he had a twin sister, Jessica, who became a famous pop star after Michael Jackson overheard her singing in the bathroom and cast her in his video for “Scream” instead of Janet. In reality, Jason’s life was considerably lonelier.

Once, when Jason was around ten, he put on his grandmother’s slip intending to “do a little show.” His uncle walked in as Jason was mid-pirouette and made him change. As Jason got older, he got bigger—“two hundred and mumble mumble pounds”—and gayer, though he wasn’t sure anyone could tell. Then, one day, Jason was hanging out with his cousin and their friends, when he noticed they were watching him closely. Studying him.

“Yes,” his cousin said. “Yes. No. No. No. Yes. YES.”

“What are you doing?” Jason asked.

“I’m saying when you’re acting like a girl and when you’re not,” his cousin explained.

Jason hadn’t realized he seemed feminine to other people. He’d never really thought about his gender as a performance—a show. To fit in, he let his cousin coach him on how to be more manly.

Overall, life wasn’t bad—he got to go to summer camp and Disneyland, and his grandmother loved him—but there was lots of crying and slammed doors and frustration. In high school, he started going out with some cool kids, smoking weed, and downing beers. He went away to school in Boston but was kicked out for partying. He moved back in with Grandma Ruth and went out every night. Once, he was so confused and foggy from all the partying, he left the house for that night’s adventure wearing two different shoes. He was suffocating in his grandmother’s comfortable house. She knew it, too. One day, when he was twenty-six years old, he came home after yet another night spent dancing until five in the morning. “I love you for staying with me,” Grandma Ruth said. “But you need to live your life.”

But what was his life? Jason loved fashion, celebrities, and money. He had always dreamed about living in the biggest city, with the baddest, most important people. Soon after he arrived in New York, he reconnected with a rich girl he’d met studying graphic design in San Francisco. She and her friends were the kind of people Jason wanted to be around, the kind who regularly spent one thousand five hundred dollars on bottle service in a nightclub and vacationed in the Caribbean when the weather got cold. Jason soon fell into a routine. After work, he’d go to Metropolitan in Williamsburg for happy hour. He’d discovered it after fleeing some terrible bar full of straight people playing video games. He ran three blocks in the pouring rain and entered a dingy room full of sparkling, sexy gay men dancing to *NSYNC. At Metropolitan, he’d have a couple of beers most nights and then end up in Manhattan clubbing with his posh friends. It was a borrowed glamour, but it was glamorous nonetheless. For his birthday, they had taken him for drinks at the Jane Hotel in the West Village. He wore a silk canary-yellow button-down shirt, a gauzy blue fascinator, and a swipe of eyeshadow. The music was good, and so he lost all six foot four inches of his gay self on the dance floor. As he danced, a crowd slowly collected around him. There was no one who looked like him in the club, and he could sense that people were taking pictures. It was the same feeling he’d had when he burst into spontaneous song-and-dance numbers at summer camp. He loved people’s eyes on him, to see that he was making them laugh. But he didn’t know how to hold their attention for longer than a song or a joke. He thought he was special, but he didn’t know what to do about it. He sometimes danced or showed off while waiting for the bus, to try to get people to pay attention to him, and because he believed dancing made the bus come faster. But that was hardly a talent.

While Jason was scheming on how to rise up in the world, everything came crashing down. One night, he was so sloppy drunk he pissed off his friend’s boyfriend. They stopped inviting him to the clubs. Suddenly, he had no crew, no bottle service, and very little money. What he did have, though, was Metropolitan.

Metro, as it’s known to locals, was the biggest, busiest gay bar in Brooklyn. Unassuming, on a residential street, it welcomed Jason with open arms. During the week, regulars gathered at the bar or pool table. In the summer, chatty groups of gay men and lesbians ate burgers and smoked cigarettes in the massive backyard. It was a dive, not a destination, and after a few months, the other regulars knew Jason’s name, asked about his day and his grandmother’s health, and bought him beers. As he plotted his return to the splendor of Manhattan nightlife, Jason took refuge among his fellow salty queers.

That winter, four evenings a week, Jason hung coats and handed out tickets. He didn’t make a lot of money, but he met so many people—some of them celebrities, like clothing designer Alexander Wang. He was offered so many drugs. He loved it. He was still nobody, but the proximity to fame—and the pills and powders—made him feel one step closer to being somebody. In the Bay Area, Jason had sometimes dressed in drag for house parties and made people call him Jacquèline Baptiste. Just for fun, he started showing up to work coat check with a shimmery arch painted across his eyelids.

“Ooooh, you’re wearing eyeshadow, I love it,” people cooed as they handed him their coats—and left noticeably bigger tips.

You like this? Jason thought to himself. How about if I come wearing lipstick, too?

One night before he went to the bar, Jason had a friend do his makeup, and, an hour into his shift, a very drunk woman tipped him fifty dollars. Real money. This is something I could get into, Jason realized, and from then on he always worked coat check in makeup. Over the course of the winter, he added a wig, a tiny top hat, a bright red boa, and an obscene amount of glitter to his look. One night, Jason ran into a guy he’d slept with a few months earlier.

“Hello, Merry Cherry.” The man came over to greet him with his coat.

“Merry Cherry?” Jason asked.

The man laughed, “I don’t remember your name, but you were wearing red the last time I saw you and just seemed so happy. So I think of you as ‘Merry Cherry.’?” Jason waved his hand in front of the man and made a motion to snatch some imaginary object. “I’m taking that name,” he announced.

Jason began introducing himself as Merrie Cherry whenever he was out. The handle was both sincere—he was merry—and satirical. “Mary” being a long-standing term of endearment and sometimes ridicule among gay men. He thought it was the perfect drag name.

Spring was approaching and, with it, the end of coat check, but Jason wasn’t ready to go back to being a bored regular trapped in a day job, and he certainly didn’t want to give up the extra cash. Jason thought of how much more excited people were when he wore makeup and a wig. In his final week, he cornered one of the bar’s owners and pitched him an idea. He wanted to host a drag competition. The owner looked doubtful. Sometimes drag queens came in to meet up with friends after a gig in Manhattan, but there were no drag shows at Metropolitan. The New York City drag scene had waxed and waned in size and popularity over the past hundred years. In some eras, shows had been wild; in others, artfully restrained. Performances popped up in dive bars, nightclubs, dance halls, and theaters. But there had never been much drag in Brooklyn. In 2012, most shows took place at well-established Manhattan gay bars where a group of experienced performers and promoters determined who was good, who got booked, and who got paid. But Jason was adamant. His secret talent, he’d realized, was getting people to pay attention to him: on the dance floor, at the bar, even while hanging up their coats. If he could entertain that easily, then why couldn’t he draw a crowd to Brooklyn for a drag show? Jason pushed and prodded, and the owner relented.

“You have one chance,” he said. “But if it isn’t successful, it’s going to be a one-time thing.” He agreed to give Jason one hundred dollars to host and organize, one hundred to pay a DJ, and fifty bucks for the winner. Jason left Metro and walked out into the cool spring night, a queer man, in the early years of a new millennium, in search of the holy trinity of show business: steady money, good times, and a stage.

Drag was fun, no question. And the relative newness of drag in Brooklyn created an opportunity for creative expression that was rare in a city overflowing with competitive, talented show-offs. But could it pay the rent and provide a meaningful artistic outlet? Could it give performers the supportive community they’d need when times—inevitably—got tough? And could drag do this for everyone, or only a privileged—or lucky—few? Maybe, just maybe, it could make some people’s dreams come true.…

Soon, these local performers would find the possibility of true celebrity beyond the grimy back rooms and raucous dive bars. RuPaul’s Drag Race, at first just a small show with a niche following, would become a platform capable of launching drag queens to previously unfathomable heights of fame and fortune. After decades in the shadows, these performers would step onto a much bigger stage. It would be up to them to pack the house.

CHAPTER ONE Welcome to New York City

“Don’t you fall,” Aja warned, rushing Esai Andino toward the J train, their high heels scraping along the pavement. Putting Esai in the shoes had been a risk. Even in sneakers, the fourteen-year-old boy tripped—over curbs, steps, nothing at all—pretty much every day. The fat cans of Four Loko they’d polished off while getting ready in Aja’s room hadn’t helped Esai’s composure. As soon as their makeup was dry, seventeen-year-old Aja had rushed Esai out the door and into the cold night: two Brooklyn teenagers in search of attention, cash, and adventure in the big city.

Then the pair turned a corner and, sure enough, Esai’s ankle rolled. He screeched and keeled over. Fall 2011 had been mild, but in the evening chill his breath was visible in small puffs. Esai leaned on Aja as they hobbled into the station and up the stairs.

It was their first night out in Manhattan as drag queens. Their first night trying the thing they’d been talking about for months. Earlier that day, Aja had earned fifteen dollars reading a woman’s tarot cards and used the money to buy Esai a pair of gold sparkly heels. Esai paced on the train platform, shivering and limping slightly. He had on black tights and a star-print skirt over a polka-dot bathing suit. Aja, who had been raised as a boy but prefers the pronouns “she” or “they,” was wearing a floral shirt she’d made for a class project at the High School of Fashion Industries.

They arrived at Bar-Tini on Tenth Avenue in Hell’s Kitchen early, to avoid getting carded. A drag queen named Holly Dae, who’d recently changed her name from Holly Caust, was hosting a competition for newcomers called Beat That Face! In the drag world, “beat” could be a noun or a verb meaning a face of makeup or the act of applying makeup. Esai had chosen a drag name: Naya Kimora, because he loved Kimora Lee Simmons, the fashion designer and former wife of hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons. Aja’s name came from the chorus of a catchy Bollywood song. The other queens there had on long dresses and shiny, blond, expensive-looking wigs. Aja and Esai should have felt out of place—conspicuously underage and unpolished—but alcohol had steadied their nerves.

The bar filled up. When it was Esai’s turn to perform, he collected himself at the center of the stage and waited for the DJ to cue his music. The drums began, and Esai started swinging his hips, turning slowly in a circle.

Esai lip-synched as JLo sang, “Let all the heat pour doooown.”

The shoes chewed into Esai’s feet. The beat hit. He ignored the throbbing in his ankle, kicked his leg in front of him, pivoted, and began to twerk. People in the room tittered and politely cheered.

“Dance for your man,” JLo commanded. “Put your hands up in the air-air-air—whoa oh-oh-oh,” she sang. It was a good thing the words were simple, because he had not practiced. Esai left the stage panting and joined Aja, who had performed “Judas” by Lady Gaga, a song about toxic love, with dark synths and a wailing chorus.

Brave and foolish, these two New York City children had done something many older, wiser, and more experienced queers would never dare attempt. They’d gotten into drag, walked into a bar, and jumped onstage, without hesitation and with very little concern for the consequences. They were new, and they were rough around the edges, but even in this utterly amateur moment they had the priceless combination of guts and hunger that helped seemingly small people do big, scary things. Kicking and twirling while lip-synching in front of an audience felt like flying.

Aja lived with her mom on Hopkins and Throop in Brooklyn, where hipster Williamsburg met working-class Bushwick. She was adopted and her father had moved out when she was young. “I was wild,” she would later say about her childhood. At seven, she ran away from the babysitter, and when the police found her on the playground, Aja lied and told the cops her mother had left her there. Later, when Aja locked the door to her bedroom, her mom kicked it in. As a teenager, she dyed the family pug, Gizmo, blue with a spray bottle full of Kool-Aid and once threw an ice cube into a deep fryer in a manic desire to see what would happen. What happened was third-degree burns on her face that healed into bumpy pink scars.

People were always coming for Aja over her scars, her asthmatic wheezing, her swishy walk. Even old ladies on the street would offer unsolicited recommendations for clearer skin. “It’s not acne,” Aja would try to explain, and then sigh, “Oh, never mind.” But Aja could give as good as she got. Bigger boys threw punches and skateboards, Aja threw them back.

Aja was a pariah but talented. By twelve she was hanging out on the East River piers, where queer kids from across the borough gathered to listen to music, trade insults, and dance. Aja was a natural, quickly learning to vogue, kick, and duck-walk as the other kids cheered her on. When Aja wasn’t running the streets, she’d stay up all night perfecting sketches of Pokémon and Mortal Kombat characters. She could read a bitch to tears.

Aja met Esai, whose family occupied a crowded one-bedroom apartment a few blocks away, about a year before that first night out in drag. All the gay boys from the neighborhood crossed paths eventually. At the time, Esai was dating Timothy, a kid Aja knew from Fashion Industries. It wasn’t really Aja’s business, but she liked Esai and she couldn’t stand the thought of him going out with someone with a boxy face, bad skin, and terrible breath. When Timothy heard Aja had been talking shit and threatened to fight her, Aja’s response was a cool “Bitch, you’re nothing more than gum on the street to me.” Aja was not faking. Anyone who’d spent sixteen years disobeying a no-bullshit, always-yelling Puerto Rican mother wouldn’t be scared of much either.

After a few months, Aja’s dogged campaign against Timothy paid off. Esai showed up at Aja’s house to talk about his “boy troubles” (some kid had sent Esai a Facebook message saying he’d been sleeping with Timothy, too) and they bonded over their disgust for Esai’s—now ex—boyfriend. Aja felt protective of Esai. No one seemed to be looking out for him. Some of his close family members were moody and unpredictable—raging one day and sulking the next. Others were like ghosts in the house; the only signs of life were the liquor bottles they hid in the couches and cabinets. Esai’s grandmother, who was from the Dominican Republic, tried to look out for him as best she could, but Esai, feminine and quiet, was basically on his own. Before he was old enough to grow facial hair, he was taking the train to gay house parties in the Bronx where he’d lie about his age and guzzle alcohol. Esai and Aja started hooking up. They’d both been with guys before, but this felt different. Aja wasn’t used to being with someone so young. She thought she could help Esai avoid some of the struggle and drama she’d gone through.

For a while, they were a good match. While Aja sometimes tried to butch up, Esai never hid his girlishness. “I did not give a shit what anyone had to say,” Esai later said about those early years. Ever since he was a little boy, he loved lip gloss and short shorts. His mother would buy him oversized pants and, by the time he was twelve, he was having friends with sewing machines tailor them to show off his ass and thighs. He wondered if he liked rainbows and sparkly clothes because he was actually a woman. In seventh grade, he asked a gynecologist about a prescription for female hormones. The doctor referred him to a therapist. Esai later said this was how he figured out that, no, he wasn’t a woman, he just “wanted to look so soft and cunt” and, to him, that meant manicured nails, crop tops, and a big rhinestone Victoria’s Secret bag.

As a kid, Aja would sometimes steal her cousin’s skirt and line her lips in dark red to do a furious impression of the crass, no-nonsense former supermodel and America’s Next Top Model judge Janice Dickinson falling down the stairs. Aja loved people like Janice Dickinson and Tiffany Pollard, who were fun to watch on TV. “I was always very thoroughly entertained by people who just didn’t really give a fuck,” she later said. The impression had her family howling with laughter and Aja basked in the attention. But it wasn’t until 2011, after Aja and Esai had been hanging out for about six months, that she began to consider calling herself a drag queen. One of the trans girls at the piers told Aja that drag queens made money giving lip sync shows at gay bars in Manhattan. Aja and Esai had both heard of drag queens—men who dressed up as women and performed songs onstage—but they had never really paid them much attention. Now, Aja was intrigued. Money was always tight at home, but it had gotten especially so lately. A few years before, bullies had broken Aja’s arm, and her mom had stayed with her in the hospital, missing so much work she lost her job. They lived close to the poverty line, but what set them apart from many other families in the neighborhood was the fact that Aja’s mom owned her house. It was the foundation of their security and their relationship, the thing that protected them when Aja’s dad left. After her mom lost her job she couldn’t afford her storage space, and so she moved what felt like fifty Tupperware containers full of holiday decorations and old clothes into the house. These hoarding tendencies, her mom’s refusal to throw away something she’d paid money for, had caught up with them and, just as they were at their poorest, they were surrounded by stuff. At one point, Aja came home to find that the lights had been shut off. On another occasion, she and her mom had to make an order of pork fried rice and chicken wings last for several days. Her mother made it clear that once Aja was eighteen she was going to have to support herself. Feeling overwhelmed and powerless, Aja messaged strangers on the internet, chased bullies in city parks, danced with friends at the piers, while, thanks to what Aja thought of as “the grace of higher energies,” her mom managed to hold on to her house. Esai had started crashing with them more regularly, and Aja was desperate to bring in some cash, but hated the idea of a normal job. While voguing had originated in the queer ballroom scene, where kids of color found community and solace competing in categories like “face,” “realness,” and “body,” being a drag queen meant entertaining other gays in bars and nightclubs. Those ballroom queens who ventured into the drag world found they could make real money with their fierce attitude and dance skills, but they were expected to dress accordingly—wigs, makeup, and stylish looks that sold the fantasy of a diva, tough girl, or pop princess. Drag required an outsized alter ego that had the power to make an audience laugh, cry, or get excited—that made them feel something. Drag in bars, as Aja and Esai would learn, existed at the intersection of commerce and art and consisted of doing things Aja loved—lip-synching, dancing, looking cute—but for money. It sounded too good to be true.

Esai was already used to wearing girls’ clothes, so it made sense to dress him up, too. Though Esai was more naturally feminine on the streets, Aja was the one who knew how to paint to look really female. Posing for photos outside the house, Esai looked like a girl on her way to church: button-down floral shirt, pleated skirt, white tights. Esai didn’t have any money for makeup, and no way was he going to ask his father to buy him some, so he mopped it from a local Rite Aid. Aja showed him how to use the stolen foundation and concealer, then they snuck into Aja’s brother’s house to borrow her sister-in-law’s tiny skirts and dresses.

In the regular world, full of tired, yelling, frustrated people, Aja was treated like a nuisance, a person to be controlled or ignored. But dressed up in drag, Aja felt like someone else entirely. She felt special, not because of scars, or a lisp, or asthma, but because she was fabulous, glamorous, or shocking. In drag, Aja was strong and beautiful in ways she hadn’t thought a boy could be. For the first time ever, Aja didn’t want to hide. She wanted to be out in the world. This was a superhero cape complete with mystical powers. The teens hosted a drag show in Aja’s living room. Fifty kids whooped, hollered, and jumped on the furniture as they lip-synched with abandon. Eager to test the moneymaking potential of this fabulous new persona, Aja scoured Facebook looking for drag shows and parties at Manhattan gay bars. For Esai, drag had become his escape from the gloomy atmosphere of his grandmother’s house. He was happiest, in his words, “all pumped and perused,” dressed up like a stylish woman. He wasn’t going to be left behind. He asked Aja—the only other person he knew who did drag—to be his drag mother and take him out. Aja took to the role; it felt natural to be in charge.

In the fall of 2011, hours before their first Manhattan performances, they’d sat in Aja’s bedroom, chugging their Four Lokos while Aja painted Esai’s face and noticed that the gap between the younger boy’s two front teeth made him look even more girlish.

After their performances, Holly, the host at Bar-Tini, called all the contestants up for the judging. Aja and Esai bounded onto the stage and stood next to the other competitors. All the others were aiming for what they called “fishiness,” an arguably disparaging term that describes passable femininity—looking, moving, and talking like a woman. It reminded Esai of what he’d heard about drag pageants, where queens competed in categories like “evening gown,” “swimsuit,” and “talent,” and the crown went to the most poised and put-together queen.

Despite Aja’s efforts, Esai’s makeup was thick and cracked. Their chins were square and reddish, like the shape and texture of a brick. “Grawlick chinnula” was how Esai and Aja sometimes insulted each other when their faces looked particularly busted. They were dressed in polyester skirts that covered too much of their legs and looked much more like schoolgirls than superstars.

None of this was lost on the judges.

“I loved your energy,” said one judge. “But your outfit. Oooh, girl.”

“Your performance was good,” said another. “But you look…” She trailed off.

“You look just horrible,” said a third.

Aja understood that they were long shots—it was their first time out, after all—but she hadn’t been prepared to fail so spectacularly. She’d tried to create the illusion of a flat crotch with duct tape, what’s known as “tucking.” During the judging, the other queens made sure to point out that the silver of the tape was visible. Embarrassed by the reception and annoyed with themselves for giving a fuck, Esai and Aja left the club and jumped the turnstile for a silent ride back to Brooklyn.

Aja would later describe that night as both the beginning of her drag career and a continuation of all her troubles. Yet another sign that, no matter how hard she tried, no matter what she did, people would never accept her and would always stand in her way.

Aja and Esai, like so many Brooklyn drag performers who got their start during the second decade of the twenty-first century, were striving to make money as artists during an unprecedented moment in gay culture. A cadre of drag performers that included Thorgy Thor, Merrie Cherry, Horrorchata, Switch n’ Play, and Sasha Velour—would be the engine of this influential and innovative scene. Drag had long brought queer people moments of acceptance and rejection, but now it would also confer respect and visibility in the wider world. What Aja sensed back in 2011, before she was old enough to vote or even drive a car in New York State, was the growing power and influence of gay people—especially gay people in New York City—to make a performer’s dreams come true.

Not that these opportunities would be equally—or fairly—distributed. Any truly ambitious performer had a rough road to stardom.… Years later, recounting her defeat at the Manhattan show, Aja was still bitter. As her emotions got hotter, her voice grew raspier and her Brooklyn accent thicker. “These bitches never made it easy for me,” she would gripe, and Esai would laugh.

“Girl, your face was a brick,” he said. “We looked horrible.”

A stage is a stage, no matter how small. For as long as there have been gay bars, there have been people who elbowed their way to the front of the room to find self-esteem, confidence, and opportunity by dancing, singing a song, or telling some jokes. If they were good, they became figureheads of the scene. From Alabama to Alaska, these performers brought glamour, excitement, and entertainment to the often maligned or ignored subcultures that formed in tiny rooms and dingy queer bars. On those nights when they were the flashiest creatures in the room, they found a certain type of fame among a crowd that hadn’t yet been represented on Broadway stages, television, or in Hollywood. If they cultivated an alluring personality, gave good shows, and put the time in, they were recognized and respected by the network of friends, lovers, and acquaintances who made up the gay world in their particular city or town. Fame doesn’t always mean your face on a Times Square billboard; it can just as easily be friends of friends you’ve never met, whose names you do not know, telling stories about your exploits and adventures. Unnoticed by the wider world, the gay community had quietly been forging stars like this for generations. Now, it was about to mint a few more.

On a chilly November evening in 2011, Jason Daniels was nursing a beer at Metropolitan in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood when one of the owners mentioned they needed someone to work coat check over the winter. Jason perked up. He had moved to New York City two years earlier from Berkeley, California, with two suitcases and three months of rent money, hoping to be somebody. He wasn’t sure who, exactly, but somebody. Now, at twenty-eight years old, he found himself wasting his days in a windowless office, entering numbers into spreadsheets for a nonprofit alongside an overbearing boss and a bunch of uptight coworkers. He was living like a nobody in the most important place on earth, paying too much rent for too little space on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Even while people partied, screwed, and got rich all around him, Jason was friendless, bored, and broke. It sucked. Coat check seemed a step up, however small, plus he could use the money.

In Berkeley, he’d been raised mostly by his grandmother Ruth, who knew he liked boys but rarely talked about it. An only child, Jason spent a lot of time alone imagining a world where people wanted to get to know him. In these fantasies, he lived on Long Island—a place he’d heard about on TV—and belonged to the wealthiest Black family in the world. Everyone was fascinated by his rich, stylish parents, and all of Jason’s friends were rich and stylish, too. Jason imagined that he had a twin sister, Jessica, who became a famous pop star after Michael Jackson overheard her singing in the bathroom and cast her in his video for “Scream” instead of Janet. In reality, Jason’s life was considerably lonelier.

Once, when Jason was around ten, he put on his grandmother’s slip intending to “do a little show.” His uncle walked in as Jason was mid-pirouette and made him change. As Jason got older, he got bigger—“two hundred and mumble mumble pounds”—and gayer, though he wasn’t sure anyone could tell. Then, one day, Jason was hanging out with his cousin and their friends, when he noticed they were watching him closely. Studying him.

“Yes,” his cousin said. “Yes. No. No. No. Yes. YES.”

“What are you doing?” Jason asked.

“I’m saying when you’re acting like a girl and when you’re not,” his cousin explained.

Jason hadn’t realized he seemed feminine to other people. He’d never really thought about his gender as a performance—a show. To fit in, he let his cousin coach him on how to be more manly.

Overall, life wasn’t bad—he got to go to summer camp and Disneyland, and his grandmother loved him—but there was lots of crying and slammed doors and frustration. In high school, he started going out with some cool kids, smoking weed, and downing beers. He went away to school in Boston but was kicked out for partying. He moved back in with Grandma Ruth and went out every night. Once, he was so confused and foggy from all the partying, he left the house for that night’s adventure wearing two different shoes. He was suffocating in his grandmother’s comfortable house. She knew it, too. One day, when he was twenty-six years old, he came home after yet another night spent dancing until five in the morning. “I love you for staying with me,” Grandma Ruth said. “But you need to live your life.”

But what was his life? Jason loved fashion, celebrities, and money. He had always dreamed about living in the biggest city, with the baddest, most important people. Soon after he arrived in New York, he reconnected with a rich girl he’d met studying graphic design in San Francisco. She and her friends were the kind of people Jason wanted to be around, the kind who regularly spent one thousand five hundred dollars on bottle service in a nightclub and vacationed in the Caribbean when the weather got cold. Jason soon fell into a routine. After work, he’d go to Metropolitan in Williamsburg for happy hour. He’d discovered it after fleeing some terrible bar full of straight people playing video games. He ran three blocks in the pouring rain and entered a dingy room full of sparkling, sexy gay men dancing to *NSYNC. At Metropolitan, he’d have a couple of beers most nights and then end up in Manhattan clubbing with his posh friends. It was a borrowed glamour, but it was glamorous nonetheless. For his birthday, they had taken him for drinks at the Jane Hotel in the West Village. He wore a silk canary-yellow button-down shirt, a gauzy blue fascinator, and a swipe of eyeshadow. The music was good, and so he lost all six foot four inches of his gay self on the dance floor. As he danced, a crowd slowly collected around him. There was no one who looked like him in the club, and he could sense that people were taking pictures. It was the same feeling he’d had when he burst into spontaneous song-and-dance numbers at summer camp. He loved people’s eyes on him, to see that he was making them laugh. But he didn’t know how to hold their attention for longer than a song or a joke. He thought he was special, but he didn’t know what to do about it. He sometimes danced or showed off while waiting for the bus, to try to get people to pay attention to him, and because he believed dancing made the bus come faster. But that was hardly a talent.

While Jason was scheming on how to rise up in the world, everything came crashing down. One night, he was so sloppy drunk he pissed off his friend’s boyfriend. They stopped inviting him to the clubs. Suddenly, he had no crew, no bottle service, and very little money. What he did have, though, was Metropolitan.

Metro, as it’s known to locals, was the biggest, busiest gay bar in Brooklyn. Unassuming, on a residential street, it welcomed Jason with open arms. During the week, regulars gathered at the bar or pool table. In the summer, chatty groups of gay men and lesbians ate burgers and smoked cigarettes in the massive backyard. It was a dive, not a destination, and after a few months, the other regulars knew Jason’s name, asked about his day and his grandmother’s health, and bought him beers. As he plotted his return to the splendor of Manhattan nightlife, Jason took refuge among his fellow salty queers.

That winter, four evenings a week, Jason hung coats and handed out tickets. He didn’t make a lot of money, but he met so many people—some of them celebrities, like clothing designer Alexander Wang. He was offered so many drugs. He loved it. He was still nobody, but the proximity to fame—and the pills and powders—made him feel one step closer to being somebody. In the Bay Area, Jason had sometimes dressed in drag for house parties and made people call him Jacquèline Baptiste. Just for fun, he started showing up to work coat check with a shimmery arch painted across his eyelids.

“Ooooh, you’re wearing eyeshadow, I love it,” people cooed as they handed him their coats—and left noticeably bigger tips.

You like this? Jason thought to himself. How about if I come wearing lipstick, too?

One night before he went to the bar, Jason had a friend do his makeup, and, an hour into his shift, a very drunk woman tipped him fifty dollars. Real money. This is something I could get into, Jason realized, and from then on he always worked coat check in makeup. Over the course of the winter, he added a wig, a tiny top hat, a bright red boa, and an obscene amount of glitter to his look. One night, Jason ran into a guy he’d slept with a few months earlier.

“Hello, Merry Cherry.” The man came over to greet him with his coat.

“Merry Cherry?” Jason asked.

The man laughed, “I don’t remember your name, but you were wearing red the last time I saw you and just seemed so happy. So I think of you as ‘Merry Cherry.’?” Jason waved his hand in front of the man and made a motion to snatch some imaginary object. “I’m taking that name,” he announced.

Jason began introducing himself as Merrie Cherry whenever he was out. The handle was both sincere—he was merry—and satirical. “Mary” being a long-standing term of endearment and sometimes ridicule among gay men. He thought it was the perfect drag name.

Spring was approaching and, with it, the end of coat check, but Jason wasn’t ready to go back to being a bored regular trapped in a day job, and he certainly didn’t want to give up the extra cash. Jason thought of how much more excited people were when he wore makeup and a wig. In his final week, he cornered one of the bar’s owners and pitched him an idea. He wanted to host a drag competition. The owner looked doubtful. Sometimes drag queens came in to meet up with friends after a gig in Manhattan, but there were no drag shows at Metropolitan. The New York City drag scene had waxed and waned in size and popularity over the past hundred years. In some eras, shows had been wild; in others, artfully restrained. Performances popped up in dive bars, nightclubs, dance halls, and theaters. But there had never been much drag in Brooklyn. In 2012, most shows took place at well-established Manhattan gay bars where a group of experienced performers and promoters determined who was good, who got booked, and who got paid. But Jason was adamant. His secret talent, he’d realized, was getting people to pay attention to him: on the dance floor, at the bar, even while hanging up their coats. If he could entertain that easily, then why couldn’t he draw a crowd to Brooklyn for a drag show? Jason pushed and prodded, and the owner relented.

“You have one chance,” he said. “But if it isn’t successful, it’s going to be a one-time thing.” He agreed to give Jason one hundred dollars to host and organize, one hundred to pay a DJ, and fifty bucks for the winner. Jason left Metro and walked out into the cool spring night, a queer man, in the early years of a new millennium, in search of the holy trinity of show business: steady money, good times, and a stage.

Drag was fun, no question. And the relative newness of drag in Brooklyn created an opportunity for creative expression that was rare in a city overflowing with competitive, talented show-offs. But could it pay the rent and provide a meaningful artistic outlet? Could it give performers the supportive community they’d need when times—inevitably—got tough? And could drag do this for everyone, or only a privileged—or lucky—few? Maybe, just maybe, it could make some people’s dreams come true.…

Soon, these local performers would find the possibility of true celebrity beyond the grimy back rooms and raucous dive bars. RuPaul’s Drag Race, at first just a small show with a niche following, would become a platform capable of launching drag queens to previously unfathomable heights of fame and fortune. After decades in the shadows, these performers would step onto a much bigger stage. It would be up to them to pack the house.

Recenzii

“Funny, poignant, dishy and even enlightening... it’s the story of America now.”

—Alexander Chee, The New York Times

“Takes us tumbling down a glittery rabbit hole... a vivid portrait of a singular subculture: joyful and scrappy.”

—Esquire

“Original and compelling… stitched together with great respect and love.”

—The Guardian

“If you thought you knew everything there was to know about drag in New York, think again. How You Get Famous tackles Brooklyn’s rich and often labyrinthine history of drag with journalistic precision. Never afraid to embrace chaos and nuance, this is a book that’s both informative and, like so many of the divas it takes as its subjects, wildly entertaining.”

—John Paul Brammer, author of Hola Papi

“Can a queer subculture hit the big time without losing its edge? In this richly reported account, Pasulka takes readers on a riotous tour through a spiky demimonde on the verge of breaking through.”

—Sara Marcus, author of Girls to the Front

“Nicole Pasulka brings the underground world of Brooklyn drag to fabulous life, exploring the triumphs, heartaches, compromises, and catastrophes of trying to achieve fame in a fishbowl—all reality, no television.”

—Hugh Ryan, author of When Brooklyn Was Queer

“Every generation moves to New York City for fame, fortune, and love; this one did it in heels. Nicole Pasulka has written a shady and fabulous history of our time.”

—Choire Sicha, author of Very Recent History

“Dripping in plush detail and drama.”

—Mother Jones

“If you like to have a good time, you want to read this book!”

—Buzzfeed

“Spills the hot-mess tea—then reads the leaves to divine the myriad things drag has meant and could be.”

—Jeremy Atherton Lin, author of Gay Bar

—Alexander Chee, The New York Times

“Takes us tumbling down a glittery rabbit hole... a vivid portrait of a singular subculture: joyful and scrappy.”

—Esquire

“Original and compelling… stitched together with great respect and love.”

—The Guardian

“If you thought you knew everything there was to know about drag in New York, think again. How You Get Famous tackles Brooklyn’s rich and often labyrinthine history of drag with journalistic precision. Never afraid to embrace chaos and nuance, this is a book that’s both informative and, like so many of the divas it takes as its subjects, wildly entertaining.”

—John Paul Brammer, author of Hola Papi

“Can a queer subculture hit the big time without losing its edge? In this richly reported account, Pasulka takes readers on a riotous tour through a spiky demimonde on the verge of breaking through.”

—Sara Marcus, author of Girls to the Front

“Nicole Pasulka brings the underground world of Brooklyn drag to fabulous life, exploring the triumphs, heartaches, compromises, and catastrophes of trying to achieve fame in a fishbowl—all reality, no television.”

—Hugh Ryan, author of When Brooklyn Was Queer

“Every generation moves to New York City for fame, fortune, and love; this one did it in heels. Nicole Pasulka has written a shady and fabulous history of our time.”

—Choire Sicha, author of Very Recent History

“Dripping in plush detail and drama.”

—Mother Jones

“If you like to have a good time, you want to read this book!”

—Buzzfeed

“Spills the hot-mess tea—then reads the leaves to divine the myriad things drag has meant and could be.”

—Jeremy Atherton Lin, author of Gay Bar

Descriere

A “funny, poignant, dishy, and even enlightening” adventure through a tight-knit world of drag performers making art, mayhem, and dreaming of making it big, this book is “the story of America now” (Alexander Chee, The New York Times).