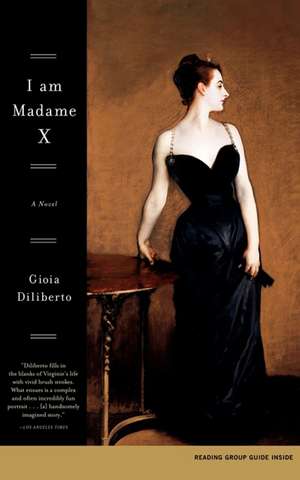

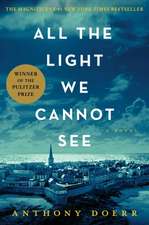

I Am Madame X: A Novel

Autor Gioia Dilibertoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 iul 2004

Preț: 104.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.98€ • 21.70$ • 16.79£

19.98€ • 21.70$ • 16.79£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743456807

ISBN-10: 0743456807

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: 1

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

ISBN-10: 0743456807

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: 1

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Notă biografică

Gioia Diliberto has written biographies of Jane Addams, Hadley Hemingway, and Brenda Frazier, as well as the critically acclaimed novels I Am Madame X and The Collection. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her family.

Extras

Chapter One

Recently, whenever I talk in my sleep -- which has been quite often lately -- I speak English. It's odd, since I've only spoken the language occasionally in half a century. But just last week, I woke Henri with some nocturnal gibberish. He roused me and repeated my mumblings as best he could, and I realized I was singing a few lines from "Oft in the Stilly Night," an old song Grandmère's servant Alzea had taught me before we fled Parlange, our sugar plantation in Louisiana. Fully awake, I can still recall a verse:

Oft in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain hath bound me,

Fond memory brings the light

Of other days around me,

The smiles, the tears, of girlhood's years,

The words of love then spoken,

The eyes that shone, now dimmed and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain hath bound me,

Sad memory brings the light

of other days around me.

Dr. Freud is right. There really is an "unconscious" mind. Perhaps mine lives in the Old South.

I'd been dreaming of Tante Julie's wedding day, of watching her glide across the wide gallery at Parlange, her pale face streaked with sweat, the pink rosebuds braided through her hair turning limp and brown in the steaming heat. She was dressed in heavy cream satin -- an old ball gown that Grandmère had dug out of a trunk the day before. Alzea had stayed up all night altering the sleeves and neckline, and I had sat beside her in the flickering candlelight of the kitchenhouse, sobbing like a baby.

I did not want Tante Julie to marry. Her fiancé, Lieutenant Lucas Rochilieu, was a short, fat toad of a man, with an ugly mole on the tip of his nose and a bloody patch over one eye from a wound he had received when he accidentally shot himself while cleaning his gun four months earlier. But I would have hated him even if he had been tall and handsome. He was stealing Tante Julie, the person I loved most in the world -- more than my baby sister Valentine, more than Mama and Papa, I'm ashamed to say.

It was August 1861, the first summer of the war. I was six. Papa, a lawyer in New Orleans, had left to fight with the mostly Creole Louisiana Regiment, and Mama, Valentine, and I had joined Grandmère at Parlange, thirty-five miles west of New Orleans on False River.

Though the adults had strictly forbidden it, I slipped off to the fields after breakfast to cut myself an armload of sugarcane. For an hour, I sat on the front lawn in the gray shade of a magnolia, peeling and eating the sweet stalks as carriages rolled up the alley of oaks. A few guests had already gathered in the parlor, and I could see them through the tall French windows talking and sipping drinks under dark portraits of my ancestors.

Most of Grandmère's slaves had run off, and there was no time to make elaborate wedding preparations. Alzea had baked some cakes and hauled the last crates of wine and champagne up from the cellar. Mama and I fashioned bouquets from the few garden flowers that hadn't shriveled in the scalding sun, and we arranged them in vases in the parlor.

The air was heavy with smoke. Some of the neighbors had taken to burning their cotton to keep it out of enemy hands, and my head began to ache from the foul air and the heat. I decided to go to the gallery to cool off and talk to Julie.

The gallery was my favorite place at Parlange. The wide porch surrounded the entire green-shuttered house and provided enough space to accommodate a small orchestra and twenty dancing couples on Saturday evenings. The back portion looked out on the colorful garden and beyond, to endless fields of waving cane. At night, the twanging notes of banjos wafted through the treetops from the Negro quarters, which were screened by a tall fence. The front gallery held a collection of wicker tables and chairs. Julie and I spent hours there talking and reading.

Like all the women in our family, Julie was small and narrow-waisted. Her straight black hair hung like curtains from a center part and framed a gentle, oval face. At twenty-eight, she was two years younger than Mama, though she seemed closer to my age. It wasn't only her uncoiffed hair. There was something childlike about her flat chest and stick arms. She had a lovely singing voice, and she painted beautifully, in a distinctive style marked by insightful realism. Years later, many artists would ask me -- beg me -- to pose for them. But Julie was the first to notice my potential. "Mimi, you have exquisite lines, and your hair! I've never seen such a glorious copper color, like the kitchenhouse kettles," she told me. She did many studies of me -- asleep on the brocade settee in the parlor, bathing in front of the fireplace in my room, on the swing in the garden -- but she refused to display these pictures or any others that she did. She stashed her canvases under her bed, unsigned, and she scrawled on the back, "Not to be shown to anyone."

Julie grew up at Parlange and never left. She was content with her quiet life and once told me she had no desire to marry, the chief point of a Creole woman's existence.

"Men are bothersome beings. I don't want to spend my days worrying about one," she said.

"But don't you want babies?" I asked.

"Chérie, if I ever had a child, I'd want it to be exactly like you. In fact, I'd want it to come into the world exactly like you, a spirited little red-haired girl who reads and converses -- and not a naked, screaming infant."

I don't remember any beaux calling on Julie. So I was surprised one evening when a portly Rebel soldier ambled up the alley of oaks, then mounted the steps. "Is Miss de Ternant, Miss Julie de Ternant, receiving this afternoon?" he asked. It was Rochilieu. He had taken the steamboat from New Orleans and he smelled of the cigars and brandy he had enjoyed on the trip.

That evening, I saw him sitting in the parlor with Grandmère and Julie. My aunt was perched stiffly on an armless "lady's" chair with billowing skirts draped around her, while Rochilieu and Grandmère talked on and on. The next morning, Grandmère announced that the marriage would take place in two days.

Now, as I approached the house, I saw that Julie was reciting her Rosary. She paced back and forth on the cypress floor of the second-floor gallery, twice stopping to lean against the railing, fifteen feet above the ground. She gazed off in the distance, over my head, as if expecting to see some far-off sail on False River. I'm certain she never noticed me. Suddenly she dropped her amber beads on the floor. Holding fistfuls of cream satin at her hips, she grabbed a white pillar and hoisted herself atop the railing. She posed there for a moment, like a ship's caryatid, her eyes closed and her chin to the sky. I thought she had resigned herself to her marriage, and this was her way of saying good-bye to maidenhood. But suddenly she let go of the pillar and slowly tumbled forward, swanning, then flipping once in the air, her dress ballooning out above her knees. By the time I jerked forward, instinctively moving to catch her with my childish arms, she had hit the ground with a dull thud.

A group of chattering adults rounding the corner of the house from the garden gasped to see the pile of satin on the lawn. Grandmère, her coffee-dyed brown hair tucked under a straw hat, ran to Julie, knocking over a butler's tray holding brown-sugar lemonade and a cornmeal pound cake. Others followed, hovering, crying. Someone called for Dr. Porter. The priest approached, but Grandmère pushed him away with her wiry arms. "Keep back!" she cried.

I stood frozen on the lawn, until a soft voice whispered in my ear, "Come with me." It was Charles, Julie and Mama's half brother. His eyes were red and filling with tears. Clasping my hand tightly, Charles led me past the murmuring circle of dark figures and up a back staircase to his room in the garçonnière. He removed a checkerboard and a box of checkers from a mahogany bookcase and arranged a game on a wicker table. "Let's play," he said.

Charles was a large boy, with a big head and a smooth, intelligent face. His blue eyes were fringed with curly black lashes the color of his straight hair -- Julie's hair -- and his mouth was a red bow. All his clothes came from Paris, and though I'm sure at times he wore homespun flannel like the other planters' sons, I recall him only in fancy breeches, broadcloth waistcoats, and stiff white linen collars. He was just six years older than I, but he had a sure sense of self and a serious manner that made him seem beyond his years. "You first," he said.

With a shaky index finger, I pushed a black checker forward. Charles responded with a red. For five minutes, we stared at the board and moved checkers silently. Finally I found the strength to ask, "Do you think Tante Julie is dead?"

"Probably," said Charles. He was trying to act manly, to speak flatly and show no emotion. But his voice came out in gulps. "The heat must have made her crazy. It's always horrible on the feast of Sainte Claire."

Charles was obsessed with the weather. He watched every change and spent hours studying the sky and the clouds. Several times a day, he consulted his Almanach français -- the American Almanac was worthless, he said -- which gave the saints' feast days and, he insisted, provided clues to weather patterns.

"Then we'll see her in heaven," I said hopefully. I knew from The Gates Ajar, an American book Papa read to me, that the gates of heaven were always open to welcome new arrivals. When I died, I would be reunited there with my lost loved ones. We would be happy angels, an unbroken circle of love, the book said, free from all trouble and harm.

Charles slid a red checker forward with two square fingers. "If only Julie had waited a few days, cooler weather would have come with the Feast of Chantal, and then she would have felt better," he said.

I placed my finger on a fat black checker, but this time I couldn't move it. The thought of waiting until my own death to see Julie -- impossibly distant, I assumed -- had stolen my resolve.

"Mimi, go on!" snapped Charles, fighting for his equilibrium.

My tears erupted in a single burst. I ran from the room, down to the end of the hallway, and hid in the large linen closet, intoxicating myself with the cool, soft linen sheets and the deep, sharp fragrance of vetiver sachets.

Parlange was Grandmère. She had won it, and she had willed it to survive. Even today, more than fifty years later, though it still stands and she is long gone, no one who lived through those times can think of the plantation without conjuring an image of her.

Grandmère's parents were Canadian immigrants who died in one of the many yellow-fever epidemics that raged through Louisiana with the summer heat. She was adopted by the plantation's original owner, Marquis Vincent de Ternant III, the descendant of a French nobleman, and his childless wife. Soon the wife died, and a few months later de Ternant married Grandmère. She was barely fourteen.

She quickly had four children -- Mama was the first. But Grandmère was an indifferent mother and thought nothing of leaving her babies behind to go off to Paris for the social season. People still talk about the stir she caused boarding steamers in New Orleans, corseted nearly to suffocation in a brocaded gown and trailed by ten slaves dressed like African royalty in silk turbans and robes. In Paris, she kept an apartment at 30, rue Miromesnil and went to theaters and the opera, where her box was next to the box of Charles Parlange, one of Napoléon's colonels. After the marquis dropped dead of a heart attack one evening in the middle of dinner, his head falling into a plate of oysters, Grandmère married Colonel Parlange and brought him to Louisiana. She renamed the plantation in his honor.

The colonel didn't last long in the choking Louisiana heat. He died two years after the wedding, leaving Grandmère with another baby, Charles. After losing two husbands, Grandmère set out to run the plantation herself. During the next year, though two of her middle children -- a boy and a girl -- died, she didn't let grief stop her from learning everything there was to know: she pored over the plantation's ledgers and diaries at night, studied weather patterns, repaired the levees and irrigation canals, and organized the army of slaves for the fall harvest.

Grandmère considered herself French, but when it came to slavery, she was an American Southerner to the marrow of her bones. She did not believe slavery was evil, even though it had been outlawed in France. She thought Negroes were ignorant savages incapable of living on their own, and she took pleasure in the failures of those who had run away from Parlange or managed to buy their freedom.

She drove her slaves hard, though she was not gratuitously cruel. She wouldn't have dreamed of selling a mother away from her children, as some planters did, and she reserved beatings for serious offenses like stealing. She rewarded industry and once sent a slave who showed a talent for carpentry to New Orleans to apprentice with a famous ébéniste. He returned to make Grandmère's massive, intricately carved bed and most of the armoires in the house. Grandmère took care of her slaves when they were sick, fed and clothed them well, and gave them Saturday nights and Sundays off.

Grandmère and Mama were only fifteen years apart. They looked like sisters, both small and wiry, with pale skin, delicate features, and masses of dark hair. By the time I came along, Grandmère's hair had turned a dull, muddy brown, the result of rinsing it once a week in coffee, and there was a hardness around her mouth and eyes, as if her determination had finally etched itself on her face.

Mama and Julie were raised at Parlange and took lessons from a French tutor. They didn't learn to speak English until they were adolescents, and they never learned to read or write it well. Of the sisters, Mama was the more robust, but Julie was the one who enjoyed roaming the fields and playing with the dogs that were always lounging on the grounds. Mama disdained the slow, uneventful pace of plantation life. "Even as a child I was bored by it," she confessed to me once. "I was born sophisticated."

During frequent trips into New Orleans with Grandmère and Julie, Mama walked on the narrow banquettes of the French Quarter, past the rows of old houses with their lacy wrought-iron balconies. She was dazzled by the gaslights, the expensive trinkets behind the glass storefronts, and the elegant couples she glimpsed through carriage windows and hotel doorways.

When Mama was eighteen and Julie sixteen, Grandmère bought a house on Burgundy Street, a headquarters from which she launched her daughters into Creole society. She hosted teas and dinners and took the girls to the opera, where they sat sipping champagne in a loge lined with red velvet. Julie was indifferent to the social hurly-burly and often declined invitations to parties. But Mama never missed one.

At a dance at the St. Louis Hotel, she met Papa. She said they fell in love the moment their eyes locked across the ballroom. The orchestra was playing a waltz, and candlelight from two enormous crystal chandeliers flickered over the twirling couples.

Papa was perhaps the most eligible bachelor in town -- tall and handsome, with flashing dark eyes and auburn hair that rippled from his forehead in glossy ridges. He was also brilliant, having studied the law and set up a practice on Camp Street by age twenty. And he was rich. His father, Philippe Avegno, had arrived in New Orleans from Italy in 1823, already wealthy from his Italian shipbuilding operation. After marrying the daughter of one of the city's most prominent Creole families, he amassed a new fortune in real estate and built a high-ceilinged mansion on Toulouse Street. The couple had ten children; Papa was the seventh.

He married Mama two months after they met, and took her to live in his father's house. "I felt like I was home for the first time in my life," Mama told me later.

It's hard to imagine what Papa saw in Mama, beyond her beauty. She was gorgeous -- with large black eyes, flawless white skin, and a slender, graceful figure. But she was prickly and prone to imagining disasters. She also was a relentless complainer, always snapping and picking at Papa. Frequently, he lost his temper with her. I'd often awake in the morning to their loud, violent shouting. I remember the servants scurrying down the hall away from my parents' bedroom, the slammed doors, and my mother's pathetic crying when the storm was over.

Decades later, long after my parents' death, I was astounded to find a copy of divorce papers in Mama's desk. A few months after Valentine was born, she'd sought to end her marriage -- an almost unthinkable act for a Catholic Creole. According to the court papers, during one of their arguments, Papa had socked Mama in the eye, drawing blood, and Mama had fled her father-in-law's home, taking Valentine and me to live in Grandmère's townhouse on Burgundy Street.

I vaguely recall moving there after Christmas one year, but I have no recollection of Papa not joining us. In fact, I have a distinct memory of him playing with me on the parlor carpet. He always was gentle and affectionate with his children. I don't believe he ever once spanked me.

Before anything could come of the divorce, the war broke out, and Papa left to fight. Grandmère thought we'd be safer at Parlange, so Mama agreed to join her.

But she didn't fit easily into the role of adult daughter living in her childhood home. Mama took no interest in helping Grandmère run the plantation, and she spent most of her time sitting on the back gallery, rocking Valentine's cradle with her foot and complaining loudly about the dearth of "congenial people" to call on or to pay calls on us. She had more grievances: the mosquitoes, the killing heat, the paucity of servants to help with the children.

Then Rochilieu arrived. With the excitement of the wedding, Mama perked up and helped eagerly with preparations, selecting the china and crystal to be used during the reception and dressing Julie's hair a few hours before the nuptials. I didn't understand why Mama was so happy about marrying Julie off to a fat, ugly old soldier. "Julie doesn't even like him!" I pointed out to Mama as I helped her collect plates from the cupboard in the dining room on the morning of the wedding. Mama looked at me sternly and said, "In the name of our family Julie must make a good match."

As it turned out, Julie did not die. She survived, though in very bad shape, with two broken legs, several cracked ribs, and a severely strained back. Each morning, Alzea picked her up and carried her from her bed to the parlor settee or to a wicker chaise on the front gallery, where Grandmère gave her the responsibility to watch for Yankee soldiers. At night, Alzea carried Julie back to bed. One day, one of the Negroes staked a pole with a white towel tacked to it on the road near our front gate, a signal to old Dr. Porter to come up to the house when he passed on his daily rounds. He fitted Julie with an elaborate steel brace that she wore under her clothes. The awful contraption chafed her skin, causing terrible sores that had to be washed twice a day.

I spent hours by her side, holding old copies of La Vie Parisienne up to her face so she could read it to me. Julie never complained about her infirmity, and seemed as cheerful and playful as ever. She composed a little English verse, which she recited to me every day:

A six-year-old child,

A six-year-old child

Is a wonderful thing to behold.

I love you, Mimi,

My six-year-old child.

Please never, ever grow old!

There was no more talk of marrying her off to Lucas Rochilieu, who had left grumpily the day after the aborted wedding.

Forever afterward, Grandmère and Mama spoke of Julie's leap from the gallery only as "a terrible accident." One day, Mama took me aside. "You must never say a word to anyone about Tante Julie's accident," she warned. "And you must never, ever ask Tante Julie about it."

Of course, I had already asked Julie why she did it. She looked at me ruefully and sighed. "Someday you'll understand, Mimi," she said. "There are things worse than death."

Though Julie's spirits stayed high, to the rest of the household her suicide attempt seemed a gloomy presage of future disaster. Even as a child, I knew that trouble was coming, that life was changing. Though the war hadn't yet stretched beyond New Orleans, Grandmère believed it was only a matter of time before Yankee soldiers marched through Parlange. Alzea made a French flag out of some old dresses and hung it from a cypress post on the front gallery as a signal of our neutrality. Still, Grandmère buried four metal chests full of cash in the garden and hid her best jewels in the hollow of an ornately carved bedpost. And she started carrying a large dagger in her belt.

Our tutor, a young man who lived in one of the pigeonniers on the front lawn, had enlisted in the Confederate Army when the war started, and no one bothered anymore with our lessons. Charles and I were left on our own most of the day to roam the woods and meadows. Sometimes we'd ride in the cane wagon out to the most distant fields and watch the workers, their backs bent against the sun as they sliced cane knives through the tall reeds. We'd go to the garden for picnics of peaches and smoked ham prepared by Alzea. Afterward we'd try to catch frogs in the stream by the side of the house. Or we'd spend hours playing with our pets at the barn. I had two chickens, which I had named Sanspareil and Papillon. Charles's pet was a brown bear cub he called Rossignol, who was chained to a thick post outside the barn. A slave had killed Rossignol's mother with a scythe after she wandered into the fields one day. Another Negro caught the cub and gave him to Charles.

The most tempting diversion of all, particularly on brutally hot days, was to sneak off to False River, a narrow ribbon-shaped lake that had formed from a bend in the vast Mississippi centuries ago. Mama had forbidden us to go near the water, even though we were good swimmers. She worried that we'd get eaten by alligators. But one day, when I was light-headed from the heat, I suggested to Charles that we go for a swim. Charles studied the sky, sniffed the air, and said, "There's no need to swim. I'm sure it's going to rain. Mama's corns were killing her this morning."

"If you won't go, I'll go by myself. You just don't want to swim because you know I'm a better swimmer than you."

"Mimi, you're a deluded child," he said in the formal, supercilious manner he used with everyone. "But if you want to be humiliated in a race, fine."

We ran down the straight driveway, across the main road, and up the bank to False River. "We'll see who's faster," I said. I pointed out a starting point near a large oak and indicated a spot about fifty yards down the bank as the finish line. We stripped down to our drawers and chemises, jumped in the water, and swam as fast as we could, furiously churning our arms.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a female figure striding toward us. Her stiff broadcloth skirt swung like a bell, and the wide ribbons of her bonnet flapped around her shoulders. At first I thought it was Mama, but as the figure drew closer I heard Grandmère's scratchy bark and saw the glistening dagger in her belt.

Charles had seen her, too, and now we stood in the muddy water up to our waists, shivering from fear under the burning white sky.

"Get out right now and put your clothes on!" Grandmère shouted. We scrambled into our things, and Grandmère pushed us up the levee, a bony, blue-veined hand on each of our backs.

When we got to the house, she took one of the long, thin keys that hung from a large ring on her belt and unlocked a door under the front stairwell. "Get in," she ordered. As soon as we were inside, she slammed the door shut and turned the key. The square enclosure was just big enough for the two of us. It smelled of damp wood. A shaft of sunlight slid under the door, providing enough light for us to see clusters of spiders and bugs.

"Mimi, you're always getting us in trouble," hissed Charles.

"And you're so perfect," I snapped.

For the next twenty minutes, we bickered and poked and nudged each other. Just when I thought I couldn't stand another second of it, I heard a rapping on the ceiling, followed by a loud plink. In the slice of sunlight at the door, I saw a key on the ground. Grandmère had left it on the table next to Julie's chaise, and Julie had pushed it off the gallery. By lying flat on my stomach, I could stretch my hand under the door and finger the cool metal key. Another scraping push, and I had it. As Charles and I freed ourselves and ran to the garden to hide, we heard Julie chirping above. "You're free, chéris! Free, free."

Our swimming adventure had put Grandmère in a particularly foul mood, and for the next week or so Charles and I stayed close to the house. One afternoon, we made a book for Julie, from a serialized novel in yellowed copies of L'Abeille, the Creole newspaper. We were cutting out the pages and sewing them together when a pale boy tore up to the house on horseback. He tied his mare to a cypress post and stomped up the steps. I went with Mama to answer the bell. The boy said nothing, but he handed her a white sheet of paper bordered in black. I couldn't read the words, but I saw the drawing of a tombstone and a weeping willow, and I knew immediately what it meant. Papa was dead.

Mama read the note with frightened eyes, then crushed the paper in her fist and fell to her knees. We both sobbed loudly, chokingly. Despite her broken relationship with Papa, or, perhaps, because of it, Mama was devastated. Grandmère, who was in the dining room helping Alzea set the table for lunch, heard us and ran in. "Papa! My papa is dead!" I cried. Grandmère crossed herself and knelt down to pray.

I ran out of the house and down the steps and the alley of oaks. I ran and ran -- so hard that my lungs swallowed my sobs -- along the banks of False River. It was a gray day, unusually cool for April, and the yellow anemones shivered along the river's edge. Eventually I came upon two farm boys fishing. Their bright blue calico shirts were the same color as their eyes, and they were dangling their feet in the sluggish water. "My papa is dead!" I cried and dropped to my knees, sobbing.

One of the boys laid down his fishing rod and rushed to my side. "There, there, little girl," he said, patting my shoulder with a hand reeking of fish. "My father is dead, too."

I later learned that Papa had been shot in the left leg on the second day of the Battle at Shiloh, and was put on a train bound for New Orleans. En route, his condition worsened and he was taken off at Camp Moore in Amite, Louisiana, where his leg was amputated above the knee. An hour later, he died.

That afternoon, Mama, Grandmère, Charles, Valentine, and I took the steamer for New Orleans. Julie stayed behind with Alzea. We arrived at Grandmère's house on Burgundy Street in late evening. Papa's coffin was in the high-ceilinged parlor, surrounded by dripping candles and white chrysanthemums. A prie-dieu stood before the casket. A line of mourners, some of them Papa's clients from his Camp Street law practice, surrounded the casket. When Mama and I entered, everyone dropped back to make room. Papa looked like he was asleep, his freckled white hands crossed over his chest and a gray blanket covering him to the waist to conceal his empty pant leg. Mama and I had been dry-eyed on the steamer, but now we both wailed uncontrollably. Grandmère pulled a nail scissors from her purse and clipped a tuft of Papa's hair, which she later had made into a bracelet for Mama.

I've tried all these years not to remember Papa as a corpse, to recall him as he looked when I saw him last. He was dressed in the uniform of the Louisiana Zouaves -- brilliant red cap, dark-blue serge jacket with gold braid on the sleeves, and baggy silk trousers. Tears spilled from his eyes as he bent to kiss me on the New Orleans wharf before he marched up a gangplank and disappeared into a large transport ship with a thousand other soldiers. As the vessel pulled out, hundreds of handkerchiefs waved from the shore, and the violent shriek of the steam whistle drowned the shouts and cries of the loved ones left behind. r

Mama and I held hands on the long carriage ride to St. Louis Cemetery, where Papa was interred in a large marble tomb next to his parents. For days afterward, Mama stayed up all night, pacing the galleries -- I could hear her muffled sobs through the walls. In the morning, she had purple circles under her eyes and walked around like a ghost, clutching a torn linen handkerchief.

The next month passed in a blur of humid, rainy days. Grandmère convinced Mama she'd feel better if she got busy, so Mama began tending to Valentine and even helping Alzea a bit with the housework -- something I had never seen her do before. Charles spent much of his time walking through the house, looking out the windows and watching the sky for climatic changes. Julie and I read and reread every book in the library. Sometimes neighbors called, sitting in the parlor on chairs pushed against the walls. Alzea would distribute palmetto fans, and people would fan themselves and chat over red wine and cornmeal cake.

Meanwhile, Grandmère worked nonstop. Though the war had caused land values to plummet, and the blockaded ports meant she couldn't sell her sugar, she was determined to keep Parlange going. She was up every morning before dawn and pacing the back gallery and reciting her Rosary, her thick heels clomping on the cypress floors. Sometimes she'd stop and curse loudly at one of the slaves who had stayed on the plantation; then she'd clasp her beads and start pacing again. Afterward she'd pin her skirt up to her knees, don a pair of men's cowhide boots, and tromp out to the fields to supervise the workers. In the evening, she balanced the ledgers by candlelight in her "office," a corner of the back gallery where she had set up an old table as her desk. She hired laborers -- poor bedraggled white men -- to replace the slaves who had left, and every Saturday morning they came to collect their wages. Grandmère would arrange several whiskey bottles and glasses on the table, and as each man approached, she would pour him a drink and place a few coins in his outstretched hand.

Doing a man's job had coarsened Grandmère and exacerbated her bad temper. She was always yelling at somebody about something, and I knew to stay out of her way.

Nothing infuriated her more than hearing a member of her household speak English. She had banned all use of "les mots Yanquis" at Parlange. In Grandmère's view, English was "la langue des voleurs," the language of thieves, because all the words were stolen from other languages, chiefly, of course, from French.

She claimed that the few times she was forced to speak English she almost dislocated her jaw, which you'd understand if you heard her pronounce, say, "biscuit" or "potato." In Grandmère's mouth, they sounded like "bee-skeet" and "pah-taht."

Only Alzea, who had been raised on an American plantation before Grandmère bought her on a New Orleans auction block, was allowed to speak English. Papa had also known English, and, unbeknownst to Grandmère, he and Alzea had taught Charles and me some of the language. But we never dared breathe a word of it in front of Grandmère.

On her birthday, Charles and I prepared a little French poem to recite to her after dinner, before the cutting of the cake. We stood in front of her chair in the parlor while Mama played softly on the dainty Pleyel piano. I was waiting for Charles to nod, our agreed-upon signal to start reciting "Oh, notre chère grandmère, oh, que nous sommes fiers."

I looked at Julie crumpled under an old shawl on the settee. She looked so sad it broke my heart. I wanted to cheer her up, so I blurted out a fragment of an English verse:

Rats, they killed the dogs and chased the cats,

And ate the cheese right out of the vats.

Mama's playing halted, and I heard Julie laugh softly behind her shawl. Grandmère stared at me with bright blue eyes. She rose slowly from her chair, walked up to me, and slapped me across the face. I ran to my room and stayed there for the rest of the evening.

I dreaded facing Grandmère the next morning at breakfast, but when I entered the dining room, it was obvious she had more important matters on her mind. Julie's former fiancé, Lucas Rochilieu, was sitting at the table, dressed in frayed, grubby grays. He had grown desperately thin in the eight months since I had seen him last, and his brown hair hung over his collar in scraggly grayish strands.

He had fought at the Battle of Shiloh with Papa, I later learned, and then gone to Vera Cruz, Mexico, on orders from President Jefferson Davis, to buy guns. He was to rejoin his regiment in Richmond, but instead he deserted, bolting for Louisiana, traveling mostly by horseback through back roads and swamps. It took him two weeks to reach his plantation in Plaquemine, where he collected some money and valuables. Now he was on his way to the Gulf of Mexico. He hoped to flag down a foreign ship to take him to France. But he had heard that Yankee troops were in the area and decided to stop off at Parlange to warn us.

"Friends, you will be attacked for sure if you stay," he said heavily. "You don't know the danger! The Yankees have been shooting women and children in their beds." Rochilieu opened his square linen napkin and draped it dramatically across his lap. He tucked into the plate of beignets Alzea had placed in front of him. His mustache moved up and down as he chewed, and I considered the large mole on his nose. If Julie hadn't thrown herself over the gallery, she'd probably have to kiss that mole every day, I thought with a shudder.

From the opposite side of the table, Mama listened intently, with her long-fingered hands folded on the table. Her engagement ring, a diamond surrounded by six small rubies, sparkled in the sunlight streaming through the windows. I thought of Papa, and my chest tightened.

"Well, I'm in favor of going with you," Mama said.

Grandmère dropped her coffee cup onto its saucer, and a spray of tan liquid splashed onto her knobby hand. "You're not leaving Par-lange!" she hissed.

"I'm not staying here and risking my daughters' deaths. Or worse, having them grow up to be country bumpkins like the Cabanel girls," Mama countered. Eulalie and Nanette Cabanel lived with their parents on a nearby plantation and were notorious for never wearing corsets, not even to pay calls or to attend church.

Ever since Papa's death, Mama had dreamed of Paris. She knew several women -- Creole war widows like herself -- who had moved to the City of Light and found, if not prosperity and happiness, at least a relative peace.

The argument that day was never resolved. But the next evening, while Charles and I were playing backgammon on the gallery, a shell whirled past the house. We looked up and saw a group of Yankee soldiers and a cannon in the middle of the road. The adults were in the parlor talking, and they ran outside when they heard the shell's high screech and, moments later, the explosion as it crashed in the garden, striking and killing one of the dogs. "My God, they're at our front door!" Grandmère cried. Mama wanted to leave at once. Instead we spent the night on mattresses in the basement. Rochilieu and Grandmère snored, and the rest of us didn't get much sleep.

The lone shell was apparently just a warning. Still, the next morning, Rochilieu said it was no longer safe for him at Parlange. If caught by the Federals, he'd be taken prisoner; if caught by the Rebels, he'd be shot as a deserter. "I'm leaving tonight, whether you come with me or not," he said.

He spent the day reading in the parlor, biding his time until night fell. No one said anything about our going with him, and I went to bed as usual at nine.

Grandmère awoke me at midnight. Holding a lighted candle, she led me through the darkened house, past the bedrooms where Charles and Julie were sleeping, and outside to the front gallery. Rochilieu and Mama, with Valentine swaddled against her chest, were inkblots on the lawn below. Beside them, the horses moved restlessly under a magnolia tree. "You're going with your mama and Lieutenant Rochilieu," Grandmère said. "Julie and Charles are staying with me." I ran to the barn to say good-bye to my chickens, Papillon and Sanspareil. Outside, Charles's bear, Rossignol, was tethered to his post, asleep. "Farewell, Rossignol," I sighed, feeling terrible that I had not had a chance to say good-bye to Charles himself.

Back at the house, Grandmère tied a gunnysack around my waist. It was heavy and pulled at my abdomen whenever I took a step. "Mimi, this is very important," she said. "There are enough gold coins in here to provide for you and your mother and sister in Paris, and you must never let it out of your sight, ever. Tu comprends? If the soldiers stop you, they will not search a child."

She kissed me on the forehead, then embraced Mama. In all my days at Parlange, I had never seen them touch each other. In fact, if I didn't know they were mother and daughter, I would have assumed they disliked each other, so chilly and formal were their relations. Yet now they gripped each other with a fierceness that frightened me.

I started to cry. "What's this? What's this?" groused Rochilieu. "We can't have crying. You'll bring the armies down on us." Mama and Grandmère broke apart. Their faces were wet.

We mounted our horses and trotted along the path by the cane fields, away from the house. The moon looked like a pearl button above the roof, and the air was sweet with the perfume of magnolias and jasmine.

Under Rochilieu's plan, we would make our way to Port Hudson on the east side of the Mississippi, then follow the Old County Road to New Orleans. From there we would take the last leg of the river to the Gulf of Mexico and the open sea, where we would flag down a French or English ship.

As we rode through the forest, Valentine stayed as still as death. But Mama, who hated horseback riding, complained constantly about her mount, her saddle, her aching back. "Shut up!" grunted Rochilieu. "For all we know, the Yanks or the Rebels are behind the next grove of trees." He wiped the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief. Once, when a rabbit ran across the path, he clutched his chest and yelped. Mama was relying on God to see us through, and she mumbled prayers all night.

At daybreak, we reached the Mississippi, where a rickety skiff was waiting on the bank. We piled into the leaky boat and pushed off. Rochilieu did the rowing. Mama held Valentine, and I lay against Mama's legs with her shawl enfolding me. I fell asleep, and when I awoke, smoke from burning cotton on the levees rose against the pink sky. A pool of water from the boat's leaky bottom had risen and soaked my shoes.

After a while, the baby began to cry. "Will you hold her a moment?" Mama said. As I stood to take Valentine from her arms, a square of sunlight broke through the trees and blinded me momentarily. The boat rocked; I stumbled. The sack of gold slid from my waist, vanishing into the muddy water with a loud plop and narrowly missing the black, scaly head of an alligator lurking nearby.

Copyright © 2003 by Gioia Diliberto

Recently, whenever I talk in my sleep -- which has been quite often lately -- I speak English. It's odd, since I've only spoken the language occasionally in half a century. But just last week, I woke Henri with some nocturnal gibberish. He roused me and repeated my mumblings as best he could, and I realized I was singing a few lines from "Oft in the Stilly Night," an old song Grandmère's servant Alzea had taught me before we fled Parlange, our sugar plantation in Louisiana. Fully awake, I can still recall a verse:

Oft in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain hath bound me,

Fond memory brings the light

Of other days around me,

The smiles, the tears, of girlhood's years,

The words of love then spoken,

The eyes that shone, now dimmed and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain hath bound me,

Sad memory brings the light

of other days around me.

Dr. Freud is right. There really is an "unconscious" mind. Perhaps mine lives in the Old South.

I'd been dreaming of Tante Julie's wedding day, of watching her glide across the wide gallery at Parlange, her pale face streaked with sweat, the pink rosebuds braided through her hair turning limp and brown in the steaming heat. She was dressed in heavy cream satin -- an old ball gown that Grandmère had dug out of a trunk the day before. Alzea had stayed up all night altering the sleeves and neckline, and I had sat beside her in the flickering candlelight of the kitchenhouse, sobbing like a baby.

I did not want Tante Julie to marry. Her fiancé, Lieutenant Lucas Rochilieu, was a short, fat toad of a man, with an ugly mole on the tip of his nose and a bloody patch over one eye from a wound he had received when he accidentally shot himself while cleaning his gun four months earlier. But I would have hated him even if he had been tall and handsome. He was stealing Tante Julie, the person I loved most in the world -- more than my baby sister Valentine, more than Mama and Papa, I'm ashamed to say.

It was August 1861, the first summer of the war. I was six. Papa, a lawyer in New Orleans, had left to fight with the mostly Creole Louisiana Regiment, and Mama, Valentine, and I had joined Grandmère at Parlange, thirty-five miles west of New Orleans on False River.

Though the adults had strictly forbidden it, I slipped off to the fields after breakfast to cut myself an armload of sugarcane. For an hour, I sat on the front lawn in the gray shade of a magnolia, peeling and eating the sweet stalks as carriages rolled up the alley of oaks. A few guests had already gathered in the parlor, and I could see them through the tall French windows talking and sipping drinks under dark portraits of my ancestors.

Most of Grandmère's slaves had run off, and there was no time to make elaborate wedding preparations. Alzea had baked some cakes and hauled the last crates of wine and champagne up from the cellar. Mama and I fashioned bouquets from the few garden flowers that hadn't shriveled in the scalding sun, and we arranged them in vases in the parlor.

The air was heavy with smoke. Some of the neighbors had taken to burning their cotton to keep it out of enemy hands, and my head began to ache from the foul air and the heat. I decided to go to the gallery to cool off and talk to Julie.

The gallery was my favorite place at Parlange. The wide porch surrounded the entire green-shuttered house and provided enough space to accommodate a small orchestra and twenty dancing couples on Saturday evenings. The back portion looked out on the colorful garden and beyond, to endless fields of waving cane. At night, the twanging notes of banjos wafted through the treetops from the Negro quarters, which were screened by a tall fence. The front gallery held a collection of wicker tables and chairs. Julie and I spent hours there talking and reading.

Like all the women in our family, Julie was small and narrow-waisted. Her straight black hair hung like curtains from a center part and framed a gentle, oval face. At twenty-eight, she was two years younger than Mama, though she seemed closer to my age. It wasn't only her uncoiffed hair. There was something childlike about her flat chest and stick arms. She had a lovely singing voice, and she painted beautifully, in a distinctive style marked by insightful realism. Years later, many artists would ask me -- beg me -- to pose for them. But Julie was the first to notice my potential. "Mimi, you have exquisite lines, and your hair! I've never seen such a glorious copper color, like the kitchenhouse kettles," she told me. She did many studies of me -- asleep on the brocade settee in the parlor, bathing in front of the fireplace in my room, on the swing in the garden -- but she refused to display these pictures or any others that she did. She stashed her canvases under her bed, unsigned, and she scrawled on the back, "Not to be shown to anyone."

Julie grew up at Parlange and never left. She was content with her quiet life and once told me she had no desire to marry, the chief point of a Creole woman's existence.

"Men are bothersome beings. I don't want to spend my days worrying about one," she said.

"But don't you want babies?" I asked.

"Chérie, if I ever had a child, I'd want it to be exactly like you. In fact, I'd want it to come into the world exactly like you, a spirited little red-haired girl who reads and converses -- and not a naked, screaming infant."

I don't remember any beaux calling on Julie. So I was surprised one evening when a portly Rebel soldier ambled up the alley of oaks, then mounted the steps. "Is Miss de Ternant, Miss Julie de Ternant, receiving this afternoon?" he asked. It was Rochilieu. He had taken the steamboat from New Orleans and he smelled of the cigars and brandy he had enjoyed on the trip.

That evening, I saw him sitting in the parlor with Grandmère and Julie. My aunt was perched stiffly on an armless "lady's" chair with billowing skirts draped around her, while Rochilieu and Grandmère talked on and on. The next morning, Grandmère announced that the marriage would take place in two days.

Now, as I approached the house, I saw that Julie was reciting her Rosary. She paced back and forth on the cypress floor of the second-floor gallery, twice stopping to lean against the railing, fifteen feet above the ground. She gazed off in the distance, over my head, as if expecting to see some far-off sail on False River. I'm certain she never noticed me. Suddenly she dropped her amber beads on the floor. Holding fistfuls of cream satin at her hips, she grabbed a white pillar and hoisted herself atop the railing. She posed there for a moment, like a ship's caryatid, her eyes closed and her chin to the sky. I thought she had resigned herself to her marriage, and this was her way of saying good-bye to maidenhood. But suddenly she let go of the pillar and slowly tumbled forward, swanning, then flipping once in the air, her dress ballooning out above her knees. By the time I jerked forward, instinctively moving to catch her with my childish arms, she had hit the ground with a dull thud.

A group of chattering adults rounding the corner of the house from the garden gasped to see the pile of satin on the lawn. Grandmère, her coffee-dyed brown hair tucked under a straw hat, ran to Julie, knocking over a butler's tray holding brown-sugar lemonade and a cornmeal pound cake. Others followed, hovering, crying. Someone called for Dr. Porter. The priest approached, but Grandmère pushed him away with her wiry arms. "Keep back!" she cried.

I stood frozen on the lawn, until a soft voice whispered in my ear, "Come with me." It was Charles, Julie and Mama's half brother. His eyes were red and filling with tears. Clasping my hand tightly, Charles led me past the murmuring circle of dark figures and up a back staircase to his room in the garçonnière. He removed a checkerboard and a box of checkers from a mahogany bookcase and arranged a game on a wicker table. "Let's play," he said.

Charles was a large boy, with a big head and a smooth, intelligent face. His blue eyes were fringed with curly black lashes the color of his straight hair -- Julie's hair -- and his mouth was a red bow. All his clothes came from Paris, and though I'm sure at times he wore homespun flannel like the other planters' sons, I recall him only in fancy breeches, broadcloth waistcoats, and stiff white linen collars. He was just six years older than I, but he had a sure sense of self and a serious manner that made him seem beyond his years. "You first," he said.

With a shaky index finger, I pushed a black checker forward. Charles responded with a red. For five minutes, we stared at the board and moved checkers silently. Finally I found the strength to ask, "Do you think Tante Julie is dead?"

"Probably," said Charles. He was trying to act manly, to speak flatly and show no emotion. But his voice came out in gulps. "The heat must have made her crazy. It's always horrible on the feast of Sainte Claire."

Charles was obsessed with the weather. He watched every change and spent hours studying the sky and the clouds. Several times a day, he consulted his Almanach français -- the American Almanac was worthless, he said -- which gave the saints' feast days and, he insisted, provided clues to weather patterns.

"Then we'll see her in heaven," I said hopefully. I knew from The Gates Ajar, an American book Papa read to me, that the gates of heaven were always open to welcome new arrivals. When I died, I would be reunited there with my lost loved ones. We would be happy angels, an unbroken circle of love, the book said, free from all trouble and harm.

Charles slid a red checker forward with two square fingers. "If only Julie had waited a few days, cooler weather would have come with the Feast of Chantal, and then she would have felt better," he said.

I placed my finger on a fat black checker, but this time I couldn't move it. The thought of waiting until my own death to see Julie -- impossibly distant, I assumed -- had stolen my resolve.

"Mimi, go on!" snapped Charles, fighting for his equilibrium.

My tears erupted in a single burst. I ran from the room, down to the end of the hallway, and hid in the large linen closet, intoxicating myself with the cool, soft linen sheets and the deep, sharp fragrance of vetiver sachets.

Parlange was Grandmère. She had won it, and she had willed it to survive. Even today, more than fifty years later, though it still stands and she is long gone, no one who lived through those times can think of the plantation without conjuring an image of her.

Grandmère's parents were Canadian immigrants who died in one of the many yellow-fever epidemics that raged through Louisiana with the summer heat. She was adopted by the plantation's original owner, Marquis Vincent de Ternant III, the descendant of a French nobleman, and his childless wife. Soon the wife died, and a few months later de Ternant married Grandmère. She was barely fourteen.

She quickly had four children -- Mama was the first. But Grandmère was an indifferent mother and thought nothing of leaving her babies behind to go off to Paris for the social season. People still talk about the stir she caused boarding steamers in New Orleans, corseted nearly to suffocation in a brocaded gown and trailed by ten slaves dressed like African royalty in silk turbans and robes. In Paris, she kept an apartment at 30, rue Miromesnil and went to theaters and the opera, where her box was next to the box of Charles Parlange, one of Napoléon's colonels. After the marquis dropped dead of a heart attack one evening in the middle of dinner, his head falling into a plate of oysters, Grandmère married Colonel Parlange and brought him to Louisiana. She renamed the plantation in his honor.

The colonel didn't last long in the choking Louisiana heat. He died two years after the wedding, leaving Grandmère with another baby, Charles. After losing two husbands, Grandmère set out to run the plantation herself. During the next year, though two of her middle children -- a boy and a girl -- died, she didn't let grief stop her from learning everything there was to know: she pored over the plantation's ledgers and diaries at night, studied weather patterns, repaired the levees and irrigation canals, and organized the army of slaves for the fall harvest.

Grandmère considered herself French, but when it came to slavery, she was an American Southerner to the marrow of her bones. She did not believe slavery was evil, even though it had been outlawed in France. She thought Negroes were ignorant savages incapable of living on their own, and she took pleasure in the failures of those who had run away from Parlange or managed to buy their freedom.

She drove her slaves hard, though she was not gratuitously cruel. She wouldn't have dreamed of selling a mother away from her children, as some planters did, and she reserved beatings for serious offenses like stealing. She rewarded industry and once sent a slave who showed a talent for carpentry to New Orleans to apprentice with a famous ébéniste. He returned to make Grandmère's massive, intricately carved bed and most of the armoires in the house. Grandmère took care of her slaves when they were sick, fed and clothed them well, and gave them Saturday nights and Sundays off.

Grandmère and Mama were only fifteen years apart. They looked like sisters, both small and wiry, with pale skin, delicate features, and masses of dark hair. By the time I came along, Grandmère's hair had turned a dull, muddy brown, the result of rinsing it once a week in coffee, and there was a hardness around her mouth and eyes, as if her determination had finally etched itself on her face.

Mama and Julie were raised at Parlange and took lessons from a French tutor. They didn't learn to speak English until they were adolescents, and they never learned to read or write it well. Of the sisters, Mama was the more robust, but Julie was the one who enjoyed roaming the fields and playing with the dogs that were always lounging on the grounds. Mama disdained the slow, uneventful pace of plantation life. "Even as a child I was bored by it," she confessed to me once. "I was born sophisticated."

During frequent trips into New Orleans with Grandmère and Julie, Mama walked on the narrow banquettes of the French Quarter, past the rows of old houses with their lacy wrought-iron balconies. She was dazzled by the gaslights, the expensive trinkets behind the glass storefronts, and the elegant couples she glimpsed through carriage windows and hotel doorways.

When Mama was eighteen and Julie sixteen, Grandmère bought a house on Burgundy Street, a headquarters from which she launched her daughters into Creole society. She hosted teas and dinners and took the girls to the opera, where they sat sipping champagne in a loge lined with red velvet. Julie was indifferent to the social hurly-burly and often declined invitations to parties. But Mama never missed one.

At a dance at the St. Louis Hotel, she met Papa. She said they fell in love the moment their eyes locked across the ballroom. The orchestra was playing a waltz, and candlelight from two enormous crystal chandeliers flickered over the twirling couples.

Papa was perhaps the most eligible bachelor in town -- tall and handsome, with flashing dark eyes and auburn hair that rippled from his forehead in glossy ridges. He was also brilliant, having studied the law and set up a practice on Camp Street by age twenty. And he was rich. His father, Philippe Avegno, had arrived in New Orleans from Italy in 1823, already wealthy from his Italian shipbuilding operation. After marrying the daughter of one of the city's most prominent Creole families, he amassed a new fortune in real estate and built a high-ceilinged mansion on Toulouse Street. The couple had ten children; Papa was the seventh.

He married Mama two months after they met, and took her to live in his father's house. "I felt like I was home for the first time in my life," Mama told me later.

It's hard to imagine what Papa saw in Mama, beyond her beauty. She was gorgeous -- with large black eyes, flawless white skin, and a slender, graceful figure. But she was prickly and prone to imagining disasters. She also was a relentless complainer, always snapping and picking at Papa. Frequently, he lost his temper with her. I'd often awake in the morning to their loud, violent shouting. I remember the servants scurrying down the hall away from my parents' bedroom, the slammed doors, and my mother's pathetic crying when the storm was over.

Decades later, long after my parents' death, I was astounded to find a copy of divorce papers in Mama's desk. A few months after Valentine was born, she'd sought to end her marriage -- an almost unthinkable act for a Catholic Creole. According to the court papers, during one of their arguments, Papa had socked Mama in the eye, drawing blood, and Mama had fled her father-in-law's home, taking Valentine and me to live in Grandmère's townhouse on Burgundy Street.

I vaguely recall moving there after Christmas one year, but I have no recollection of Papa not joining us. In fact, I have a distinct memory of him playing with me on the parlor carpet. He always was gentle and affectionate with his children. I don't believe he ever once spanked me.

Before anything could come of the divorce, the war broke out, and Papa left to fight. Grandmère thought we'd be safer at Parlange, so Mama agreed to join her.

But she didn't fit easily into the role of adult daughter living in her childhood home. Mama took no interest in helping Grandmère run the plantation, and she spent most of her time sitting on the back gallery, rocking Valentine's cradle with her foot and complaining loudly about the dearth of "congenial people" to call on or to pay calls on us. She had more grievances: the mosquitoes, the killing heat, the paucity of servants to help with the children.

Then Rochilieu arrived. With the excitement of the wedding, Mama perked up and helped eagerly with preparations, selecting the china and crystal to be used during the reception and dressing Julie's hair a few hours before the nuptials. I didn't understand why Mama was so happy about marrying Julie off to a fat, ugly old soldier. "Julie doesn't even like him!" I pointed out to Mama as I helped her collect plates from the cupboard in the dining room on the morning of the wedding. Mama looked at me sternly and said, "In the name of our family Julie must make a good match."

As it turned out, Julie did not die. She survived, though in very bad shape, with two broken legs, several cracked ribs, and a severely strained back. Each morning, Alzea picked her up and carried her from her bed to the parlor settee or to a wicker chaise on the front gallery, where Grandmère gave her the responsibility to watch for Yankee soldiers. At night, Alzea carried Julie back to bed. One day, one of the Negroes staked a pole with a white towel tacked to it on the road near our front gate, a signal to old Dr. Porter to come up to the house when he passed on his daily rounds. He fitted Julie with an elaborate steel brace that she wore under her clothes. The awful contraption chafed her skin, causing terrible sores that had to be washed twice a day.

I spent hours by her side, holding old copies of La Vie Parisienne up to her face so she could read it to me. Julie never complained about her infirmity, and seemed as cheerful and playful as ever. She composed a little English verse, which she recited to me every day:

A six-year-old child,

A six-year-old child

Is a wonderful thing to behold.

I love you, Mimi,

My six-year-old child.

Please never, ever grow old!

There was no more talk of marrying her off to Lucas Rochilieu, who had left grumpily the day after the aborted wedding.

Forever afterward, Grandmère and Mama spoke of Julie's leap from the gallery only as "a terrible accident." One day, Mama took me aside. "You must never say a word to anyone about Tante Julie's accident," she warned. "And you must never, ever ask Tante Julie about it."

Of course, I had already asked Julie why she did it. She looked at me ruefully and sighed. "Someday you'll understand, Mimi," she said. "There are things worse than death."

Though Julie's spirits stayed high, to the rest of the household her suicide attempt seemed a gloomy presage of future disaster. Even as a child, I knew that trouble was coming, that life was changing. Though the war hadn't yet stretched beyond New Orleans, Grandmère believed it was only a matter of time before Yankee soldiers marched through Parlange. Alzea made a French flag out of some old dresses and hung it from a cypress post on the front gallery as a signal of our neutrality. Still, Grandmère buried four metal chests full of cash in the garden and hid her best jewels in the hollow of an ornately carved bedpost. And she started carrying a large dagger in her belt.

Our tutor, a young man who lived in one of the pigeonniers on the front lawn, had enlisted in the Confederate Army when the war started, and no one bothered anymore with our lessons. Charles and I were left on our own most of the day to roam the woods and meadows. Sometimes we'd ride in the cane wagon out to the most distant fields and watch the workers, their backs bent against the sun as they sliced cane knives through the tall reeds. We'd go to the garden for picnics of peaches and smoked ham prepared by Alzea. Afterward we'd try to catch frogs in the stream by the side of the house. Or we'd spend hours playing with our pets at the barn. I had two chickens, which I had named Sanspareil and Papillon. Charles's pet was a brown bear cub he called Rossignol, who was chained to a thick post outside the barn. A slave had killed Rossignol's mother with a scythe after she wandered into the fields one day. Another Negro caught the cub and gave him to Charles.

The most tempting diversion of all, particularly on brutally hot days, was to sneak off to False River, a narrow ribbon-shaped lake that had formed from a bend in the vast Mississippi centuries ago. Mama had forbidden us to go near the water, even though we were good swimmers. She worried that we'd get eaten by alligators. But one day, when I was light-headed from the heat, I suggested to Charles that we go for a swim. Charles studied the sky, sniffed the air, and said, "There's no need to swim. I'm sure it's going to rain. Mama's corns were killing her this morning."

"If you won't go, I'll go by myself. You just don't want to swim because you know I'm a better swimmer than you."

"Mimi, you're a deluded child," he said in the formal, supercilious manner he used with everyone. "But if you want to be humiliated in a race, fine."

We ran down the straight driveway, across the main road, and up the bank to False River. "We'll see who's faster," I said. I pointed out a starting point near a large oak and indicated a spot about fifty yards down the bank as the finish line. We stripped down to our drawers and chemises, jumped in the water, and swam as fast as we could, furiously churning our arms.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a female figure striding toward us. Her stiff broadcloth skirt swung like a bell, and the wide ribbons of her bonnet flapped around her shoulders. At first I thought it was Mama, but as the figure drew closer I heard Grandmère's scratchy bark and saw the glistening dagger in her belt.

Charles had seen her, too, and now we stood in the muddy water up to our waists, shivering from fear under the burning white sky.

"Get out right now and put your clothes on!" Grandmère shouted. We scrambled into our things, and Grandmère pushed us up the levee, a bony, blue-veined hand on each of our backs.

When we got to the house, she took one of the long, thin keys that hung from a large ring on her belt and unlocked a door under the front stairwell. "Get in," she ordered. As soon as we were inside, she slammed the door shut and turned the key. The square enclosure was just big enough for the two of us. It smelled of damp wood. A shaft of sunlight slid under the door, providing enough light for us to see clusters of spiders and bugs.

"Mimi, you're always getting us in trouble," hissed Charles.

"And you're so perfect," I snapped.

For the next twenty minutes, we bickered and poked and nudged each other. Just when I thought I couldn't stand another second of it, I heard a rapping on the ceiling, followed by a loud plink. In the slice of sunlight at the door, I saw a key on the ground. Grandmère had left it on the table next to Julie's chaise, and Julie had pushed it off the gallery. By lying flat on my stomach, I could stretch my hand under the door and finger the cool metal key. Another scraping push, and I had it. As Charles and I freed ourselves and ran to the garden to hide, we heard Julie chirping above. "You're free, chéris! Free, free."

Our swimming adventure had put Grandmère in a particularly foul mood, and for the next week or so Charles and I stayed close to the house. One afternoon, we made a book for Julie, from a serialized novel in yellowed copies of L'Abeille, the Creole newspaper. We were cutting out the pages and sewing them together when a pale boy tore up to the house on horseback. He tied his mare to a cypress post and stomped up the steps. I went with Mama to answer the bell. The boy said nothing, but he handed her a white sheet of paper bordered in black. I couldn't read the words, but I saw the drawing of a tombstone and a weeping willow, and I knew immediately what it meant. Papa was dead.

Mama read the note with frightened eyes, then crushed the paper in her fist and fell to her knees. We both sobbed loudly, chokingly. Despite her broken relationship with Papa, or, perhaps, because of it, Mama was devastated. Grandmère, who was in the dining room helping Alzea set the table for lunch, heard us and ran in. "Papa! My papa is dead!" I cried. Grandmère crossed herself and knelt down to pray.

I ran out of the house and down the steps and the alley of oaks. I ran and ran -- so hard that my lungs swallowed my sobs -- along the banks of False River. It was a gray day, unusually cool for April, and the yellow anemones shivered along the river's edge. Eventually I came upon two farm boys fishing. Their bright blue calico shirts were the same color as their eyes, and they were dangling their feet in the sluggish water. "My papa is dead!" I cried and dropped to my knees, sobbing.

One of the boys laid down his fishing rod and rushed to my side. "There, there, little girl," he said, patting my shoulder with a hand reeking of fish. "My father is dead, too."

I later learned that Papa had been shot in the left leg on the second day of the Battle at Shiloh, and was put on a train bound for New Orleans. En route, his condition worsened and he was taken off at Camp Moore in Amite, Louisiana, where his leg was amputated above the knee. An hour later, he died.

That afternoon, Mama, Grandmère, Charles, Valentine, and I took the steamer for New Orleans. Julie stayed behind with Alzea. We arrived at Grandmère's house on Burgundy Street in late evening. Papa's coffin was in the high-ceilinged parlor, surrounded by dripping candles and white chrysanthemums. A prie-dieu stood before the casket. A line of mourners, some of them Papa's clients from his Camp Street law practice, surrounded the casket. When Mama and I entered, everyone dropped back to make room. Papa looked like he was asleep, his freckled white hands crossed over his chest and a gray blanket covering him to the waist to conceal his empty pant leg. Mama and I had been dry-eyed on the steamer, but now we both wailed uncontrollably. Grandmère pulled a nail scissors from her purse and clipped a tuft of Papa's hair, which she later had made into a bracelet for Mama.

I've tried all these years not to remember Papa as a corpse, to recall him as he looked when I saw him last. He was dressed in the uniform of the Louisiana Zouaves -- brilliant red cap, dark-blue serge jacket with gold braid on the sleeves, and baggy silk trousers. Tears spilled from his eyes as he bent to kiss me on the New Orleans wharf before he marched up a gangplank and disappeared into a large transport ship with a thousand other soldiers. As the vessel pulled out, hundreds of handkerchiefs waved from the shore, and the violent shriek of the steam whistle drowned the shouts and cries of the loved ones left behind. r

Mama and I held hands on the long carriage ride to St. Louis Cemetery, where Papa was interred in a large marble tomb next to his parents. For days afterward, Mama stayed up all night, pacing the galleries -- I could hear her muffled sobs through the walls. In the morning, she had purple circles under her eyes and walked around like a ghost, clutching a torn linen handkerchief.

The next month passed in a blur of humid, rainy days. Grandmère convinced Mama she'd feel better if she got busy, so Mama began tending to Valentine and even helping Alzea a bit with the housework -- something I had never seen her do before. Charles spent much of his time walking through the house, looking out the windows and watching the sky for climatic changes. Julie and I read and reread every book in the library. Sometimes neighbors called, sitting in the parlor on chairs pushed against the walls. Alzea would distribute palmetto fans, and people would fan themselves and chat over red wine and cornmeal cake.

Meanwhile, Grandmère worked nonstop. Though the war had caused land values to plummet, and the blockaded ports meant she couldn't sell her sugar, she was determined to keep Parlange going. She was up every morning before dawn and pacing the back gallery and reciting her Rosary, her thick heels clomping on the cypress floors. Sometimes she'd stop and curse loudly at one of the slaves who had stayed on the plantation; then she'd clasp her beads and start pacing again. Afterward she'd pin her skirt up to her knees, don a pair of men's cowhide boots, and tromp out to the fields to supervise the workers. In the evening, she balanced the ledgers by candlelight in her "office," a corner of the back gallery where she had set up an old table as her desk. She hired laborers -- poor bedraggled white men -- to replace the slaves who had left, and every Saturday morning they came to collect their wages. Grandmère would arrange several whiskey bottles and glasses on the table, and as each man approached, she would pour him a drink and place a few coins in his outstretched hand.

Doing a man's job had coarsened Grandmère and exacerbated her bad temper. She was always yelling at somebody about something, and I knew to stay out of her way.

Nothing infuriated her more than hearing a member of her household speak English. She had banned all use of "les mots Yanquis" at Parlange. In Grandmère's view, English was "la langue des voleurs," the language of thieves, because all the words were stolen from other languages, chiefly, of course, from French.

She claimed that the few times she was forced to speak English she almost dislocated her jaw, which you'd understand if you heard her pronounce, say, "biscuit" or "potato." In Grandmère's mouth, they sounded like "bee-skeet" and "pah-taht."

Only Alzea, who had been raised on an American plantation before Grandmère bought her on a New Orleans auction block, was allowed to speak English. Papa had also known English, and, unbeknownst to Grandmère, he and Alzea had taught Charles and me some of the language. But we never dared breathe a word of it in front of Grandmère.

On her birthday, Charles and I prepared a little French poem to recite to her after dinner, before the cutting of the cake. We stood in front of her chair in the parlor while Mama played softly on the dainty Pleyel piano. I was waiting for Charles to nod, our agreed-upon signal to start reciting "Oh, notre chère grandmère, oh, que nous sommes fiers."

I looked at Julie crumpled under an old shawl on the settee. She looked so sad it broke my heart. I wanted to cheer her up, so I blurted out a fragment of an English verse:

Rats, they killed the dogs and chased the cats,

And ate the cheese right out of the vats.

Mama's playing halted, and I heard Julie laugh softly behind her shawl. Grandmère stared at me with bright blue eyes. She rose slowly from her chair, walked up to me, and slapped me across the face. I ran to my room and stayed there for the rest of the evening.

I dreaded facing Grandmère the next morning at breakfast, but when I entered the dining room, it was obvious she had more important matters on her mind. Julie's former fiancé, Lucas Rochilieu, was sitting at the table, dressed in frayed, grubby grays. He had grown desperately thin in the eight months since I had seen him last, and his brown hair hung over his collar in scraggly grayish strands.

He had fought at the Battle of Shiloh with Papa, I later learned, and then gone to Vera Cruz, Mexico, on orders from President Jefferson Davis, to buy guns. He was to rejoin his regiment in Richmond, but instead he deserted, bolting for Louisiana, traveling mostly by horseback through back roads and swamps. It took him two weeks to reach his plantation in Plaquemine, where he collected some money and valuables. Now he was on his way to the Gulf of Mexico. He hoped to flag down a foreign ship to take him to France. But he had heard that Yankee troops were in the area and decided to stop off at Parlange to warn us.

"Friends, you will be attacked for sure if you stay," he said heavily. "You don't know the danger! The Yankees have been shooting women and children in their beds." Rochilieu opened his square linen napkin and draped it dramatically across his lap. He tucked into the plate of beignets Alzea had placed in front of him. His mustache moved up and down as he chewed, and I considered the large mole on his nose. If Julie hadn't thrown herself over the gallery, she'd probably have to kiss that mole every day, I thought with a shudder.

From the opposite side of the table, Mama listened intently, with her long-fingered hands folded on the table. Her engagement ring, a diamond surrounded by six small rubies, sparkled in the sunlight streaming through the windows. I thought of Papa, and my chest tightened.

"Well, I'm in favor of going with you," Mama said.

Grandmère dropped her coffee cup onto its saucer, and a spray of tan liquid splashed onto her knobby hand. "You're not leaving Par-lange!" she hissed.

"I'm not staying here and risking my daughters' deaths. Or worse, having them grow up to be country bumpkins like the Cabanel girls," Mama countered. Eulalie and Nanette Cabanel lived with their parents on a nearby plantation and were notorious for never wearing corsets, not even to pay calls or to attend church.

Ever since Papa's death, Mama had dreamed of Paris. She knew several women -- Creole war widows like herself -- who had moved to the City of Light and found, if not prosperity and happiness, at least a relative peace.

The argument that day was never resolved. But the next evening, while Charles and I were playing backgammon on the gallery, a shell whirled past the house. We looked up and saw a group of Yankee soldiers and a cannon in the middle of the road. The adults were in the parlor talking, and they ran outside when they heard the shell's high screech and, moments later, the explosion as it crashed in the garden, striking and killing one of the dogs. "My God, they're at our front door!" Grandmère cried. Mama wanted to leave at once. Instead we spent the night on mattresses in the basement. Rochilieu and Grandmère snored, and the rest of us didn't get much sleep.

The lone shell was apparently just a warning. Still, the next morning, Rochilieu said it was no longer safe for him at Parlange. If caught by the Federals, he'd be taken prisoner; if caught by the Rebels, he'd be shot as a deserter. "I'm leaving tonight, whether you come with me or not," he said.

He spent the day reading in the parlor, biding his time until night fell. No one said anything about our going with him, and I went to bed as usual at nine.

Grandmère awoke me at midnight. Holding a lighted candle, she led me through the darkened house, past the bedrooms where Charles and Julie were sleeping, and outside to the front gallery. Rochilieu and Mama, with Valentine swaddled against her chest, were inkblots on the lawn below. Beside them, the horses moved restlessly under a magnolia tree. "You're going with your mama and Lieutenant Rochilieu," Grandmère said. "Julie and Charles are staying with me." I ran to the barn to say good-bye to my chickens, Papillon and Sanspareil. Outside, Charles's bear, Rossignol, was tethered to his post, asleep. "Farewell, Rossignol," I sighed, feeling terrible that I had not had a chance to say good-bye to Charles himself.

Back at the house, Grandmère tied a gunnysack around my waist. It was heavy and pulled at my abdomen whenever I took a step. "Mimi, this is very important," she said. "There are enough gold coins in here to provide for you and your mother and sister in Paris, and you must never let it out of your sight, ever. Tu comprends? If the soldiers stop you, they will not search a child."

She kissed me on the forehead, then embraced Mama. In all my days at Parlange, I had never seen them touch each other. In fact, if I didn't know they were mother and daughter, I would have assumed they disliked each other, so chilly and formal were their relations. Yet now they gripped each other with a fierceness that frightened me.

I started to cry. "What's this? What's this?" groused Rochilieu. "We can't have crying. You'll bring the armies down on us." Mama and Grandmère broke apart. Their faces were wet.