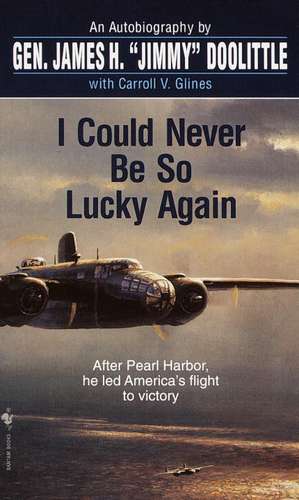

I Could Never Be So Lucky Again

Autor James Harold Doolittle Barry M. Goldwater Carroll V. Glinesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2001

General Doolittle is a giant of the twentieth century. He did it all.

As a stunt pilot, he thrilled the world with his aerial acrobatics. As a scientist, he pioneered the development of modern aviation technology.

During World War II, he served his country as a fearless and innovative air warrior, organizing and leading the devastating raid against Japan immortalized in the film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.

Now, for the first time, here is his life story — modest, revealing, and candid as only Doolittle himself can tell it.

Preț: 54.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 82

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.45€ • 11.36$ • 8.78£

10.45€ • 11.36$ • 8.78£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553584646

ISBN-10: 0553584642

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 107 x 173 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553584642

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 107 x 173 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Extras

April 18, 1942

The 16-ship Navy task force centered around the aircraft carriers Hornet and Enterprise had been steaming westward toward Japan all night. I had given my final briefing to the B-25 bomber crews on the Hornet the day before. Our job was to do what we could to put a crimp in the Japanese war effort with the 16 tons of bombs from our 16 B-25s. The bombs could do only a fraction of the damage the Japanese had inflicted on us at Pearl Harbor, but the primary purpose of the raid we were about to launch against the main island of Japan was psychological.

The Japanese people had been told they were invulnerable. Their leaders had told them Japan could never be invaded. Proof of this was the fact that Japan had been saved from invasion during the fifteenth century when a massive Chinese fleet set sail to attack Japan and was destroyed by a monsoon. From then on, the Japanese people had firmly believed they were forever protected by a “divine wind” — the kamikaze. An attack on the Japanese homeland would cause confusion in the minds of the Japanese people and sow doubt about the reliability of their leaders.

There was a second, and equally important, psychological reason for this attack. America and its allies had suffered one defeat after another in the Pacific and southern Asia. Besides the devastating surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had taken Wake Island and Guam and had driven American and Filipino forces to surrender on Bataan. Only a small force of Americans was left holding out on the island of Corregidor. America had never seen darker days. Americans badly needed a morale boost. I hoped we could give them that by a retaliatory surprise attack against the enemy’s home islands launched from a carrier, precisely as the Japanese had done at Pearl Harbor. It would be the kind of touché the Japanese military would understand. An air strike would certainly be a blow to their national morale and, furthermore, should cause the Japanese to divert aircraft and equipment from offensive operations to the defense of the home islands.

The basic plan for the raid against Japan was simple. If the Navy task force could get us within 400 to 500 miles of the Japanese coast, the B-25 medium Army bombers aboard the Hornet would launch, with carefully trained crews, against the enemy’s largest cities. Although the carrier’s deck seemed too short to allow the takeoff of a loaded B-25 land-based Army bomber, I was confident it could be done. Two lightly loaded B-25s had made trial takeoffs the previous February from the Hornet off the Virginia coast before the carrier had joined the Pacific fleet. All of the pilots had practiced a number of short-field takeoffs at an auxiliary field near Eglin Field, Florida.

I would take off first so as to arrive over Tokyo at sunset. The other crews would leave the carrier at local sunset and head for their respective targets. I would drop four 50-pound incendiary bombs on a factory area in the center of Tokyo. The resulting fires in the highly inflammable structures in the area would light up the way for the succeeding planes and steer them toward their respective targets in the Tokyo-Yokohama area, Nagoya, and the Kobe-Osaka complex. The rest of the B-25s would be loaded with four 500-pound bombs each — two incendiaries and two demolition bombs. After launching the B-25s, the Navy task force was to retreat immediately and return to Hawaii.

We would not return to the Hornet. After bombing our targets, we were to escape to China. The planes would be turned over to the new Air Force units being formed in the China-Burma-India theater.

There were five crew members in each airplane — pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, and gunner. One crew had a physician aboard — Dr. (Lieutenant) Thomas R. White — who had volunteered and qualified as a gunner so he could go. This was a fortuitous choice, as it turned out, for four members of another crew.

The State Department had tried to get permission from the Soviets for us to land in Soviet territory for refueling. This flight would have been an easy 600 miles or so after bombing the Japanese targets. But permission was denied because the Soviets were neutral vis-à-vis Japan and did not want to have another Axis power at their back door invading their country from that direction.

Therefore, after dropping its bombs, each plane was to head generally southward along the Japanese coast, then westward to Chuchow, located about 70 miles inland and about 200 miles south of Shanghai. After refueling there, we were to proceed to Chungking, 800 miles farther inland. The greatest in-flight distance we would have to fly was 2,000 miles. With the fuel tank modifications we had made and extra gas in five-gallon cans, there was enough fuel on board to fly 2,400 miles, provided the crews used the long-range cruising techniques we had practiced.

Our planes had been positioned on the deck for takeoff the evening before. The mechanics had run up their engines and made last-minute adjustments. I wanted the crews to get a good night’s sleep, but few heeded the advice of an oldster who, at 45, was twice the age of most of them. Some of the officers played poker with the Navy pilots who had been unable to fly since leaving California because our planes took up all the space on the deck. The Navy pilots and our crews wanted to recoup their individual losses before we left.

The Enterprise launched scout planes at daybreak for 200-mile searches, and fighters were sent up as cover for the task force. The weather, which had been moderately rough during the night, worsened. There was a low overcast and visibility was limited. Frequent rain squalls swept over the ships, and the sea began to heave into 30-foot crests. Gusty winds tore off the tops of the waves and blew heavy spray across the ships, drenching the deck crews. At 6:00 A.M., a scout plane returned to the Enterprise and the pilot dropped a bean bag container on the deck with a message saying he had sighted a small enemy fishing vessel and believed he had been seen by the enemy.

Admiral William F. Halsey immediately ordered all ships to swing left to avoid detection. Had the enemy vessel seen the aircraft? No one knew. The question was answered about 7:30 A.M. when another patrol vessel was sighted from the Hornet only 20,000 yards away. A Japanese radio message was intercepted by the Hornet’s radio operator from close by. One of the scout planes then sighted another small vessel 12,000 yards away. A light could be seen bobbing in the rough sea. Halsey ordered the cruiser Nashville to sink it.

Unknown to us, the Japanese had stationed a line of radio-equipped picket boats about 650 nautical miles out from the coast to warn of the approach of American ships. I went to the bridge where Captain Marc A. Mitscher briefed me on what had happened. “It looks like you’re going to have to be on your way soon,” he said. “They know we’re here.” I shook hands with Mitscher and rushed to my cabin to pack, spreading the word as I went.

Some of the B-25 crews had finished breakfast and were lounging in their cabins; others were shaving and getting ready to eat; several may have still been dozing. A few had packed their bags, but I think many were completely surprised because they thought they would not be taking off until late afternoon.

At 8:00 A.M., Admiral Halsey flashed a message to the Hornet: LAUNCH PLANES X TO COL DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU.

The ear-shattering klaxon horn sounded and a booming voice ordered: “Now hear this! Now hear this! Army pilots, man your planes!”

The weather had steadily continued to worsen. The Hornet plunged into mountainous waves that sent water cascading down the deck. Rain pelted us as we ran toward our aircraft. It was not an ideal day for a mission like this one.

The well-disciplined Navy crews and our enlisted men, some of whom had slept on deck near their planes, knew what to do. Slipping and sliding on the wet deck, they ripped off engine and gun turret covers and stuffed them inside the rear hatches. Fuel tanks were topped. The mechanics pulled the props through. Cans of gasoline were filled and handed up to the gunners through the rear hatches. Ropes were unfastened and wheel chocks pu11ed away so the Navy deck handlers could maneuver the B-25s into takeoff position.

Meanwhile, the Hornet picked up speed as best it could in the rough sea and turned into the wind. The 20-knot speed of the carrier and the 30-knot wind blowing directly down the deck meant that we should be airborne safely and quickly. This ability of an aircraft carrier to turn its “airfield” into the wind is a distinct advantage. Rarely do Navy pilots have to worry about cross-wind takeoffs and landings. However, a rough sea such as the one in front of us could ruin a pilot’s day if he ignored the signals of the deck officer and tried a takeoff when the bow of the ship was heading into the waves. It was like riding a seesaw that plunged deep into the water each time the bow dipped downward.

Lieutenant Henry L. “Hank” Miller, the naval officer assigned to us at Eglin Field, Florida, to teach us how to take off in minimum distances, said good-bye to each crew. He told us to watch a blackboard he would be holding up near the ship’s “island” to give us last-minute instructions and the carrier’s heading so our navigators could compare our planes’ compasses with the ship’s heading and set their directional gyros. The navigators were very concerned about our magnetic compasses. After more than two weeks on the carrier, they would be way off calibration, especially on those planes that were tied down close to the carrier’s metal structure. With an overcast sky, the navigators wouldn’t be able to take shots of the sun or stars with their sextants. It would be dead reckoning all the way to the Japanese coast. A check on the accuracy of the compasses was essential.

My crew emerged quickly from their quarters below decks. Sergeant Paul J. Leonard, our crew chief, was one of those skilled mechanics who knew instinctively what to do. Me already had his barracks bag and toolbox stowed in the rear and was helping the deck crews get our ship into takeoff position. In the air, he would be the top turret gunner. During our training at Eglin, he had proven he was a marksman with the twin .50s. Born in 1912, he had dropped out of high school in Roswell, New Mexico, and enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1931, at the start of the Depression. He was one of those rare individuals who applied himself and became one of the most outstanding mechanics with whom I ever served. Men like him were the backbone of the nation’s air service when war began and were highly regarded for their dedication and expertise. They set high standards for the enlisted men who served with them.

Sergeant Fred A. Braemer, of Seattle, Washington, was another “old-timer.” He had joined the infantry in 1935 and transferred to the Air Corps in 1939. He had completed both bombardier and navigator training but was serving on our crew as the bombardier.

Our copilot was Lieutenant Richard E. “Dick” Cole, from Dayton, Ohio, who had completed pilot training in July 1941. Dick was a quietly competent pilot who had attended Ohio University for two years before enlisting as a Flying Cadet. If anything happened to me, I was confident that he would take over the controls of the aircraft and the leadership of the crew without hesitation.

Lieutenant Henry A. “Hank” Potter, of Pierre, South Dakota, was our navigator. Like so many young men in those days, he had also completed two years of college, the minimum for entry into flying training, and had graduated from navigator school in 1941.

I was proud of my crew and all the other volunteers who were willing to lay their lives on the line for a risky mission that I could not tell them about until we were on the carrier. Every man had proven his competence during our training at Eglin. I felt completely comfortable and confident as our B-25 was placed in takeoff position and the wheels chocked.

I knew hundreds of eyes were watching me, especially those of the B-25 crews who were to follow. If I didn’t get off successfully, I’m sure, many thought they wouldn’t be able to make it either. But I knew they would try.

I started the engines, warmed them up, and checked the magnetos. When satisfied, I gave the thumbs-up sign to the deck launching officer holding the checkered flag. As the chocks were pulled, he looked toward the bow and began to wave the flag in circles as a signal for me to push the throttles forward to the stops. At the instant the deck was beginning an upward movement, he gave me the “go” signal and I released the brakes. The B-25 followed the two white guide lines painted on the deck and we were off with feet to spare as the deck reached its maximum pitch.

We left the Hornet at 8:20 A.M. ship time. The carrier’s position was about 824 statute miles from the center of Tokyo. Its position: latitude 35º43’N, longitude 153º25’E.

I signaled Dick for wheels up and as the plane gained flying speed, I leveled off and made a 360-degree turn to come over the carrier. This gave Hank Potter a chance to compare the magnetic heading of the carrier with our compass and align the axis of the carrier with the drift sight. The course of the Hornet was displayed in large figures from the gun turret near the island. Through the use of the airplane’s compass and directional gyro, we were able to set a fairly accurate course for Tokyo.

As we headed toward Japan at low altitude, I thought about how easy the takeoff had been. If everyone followed instructions, they should have no trouble. A night takeoff would have been easy and practicable. That was something I wanted to report to Washington when I got home. It might be useful for future operations.

I began to wonder about the arrangements in China. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, China’s ruler, had not wanted us to land in China after bombing Japan for fear of extensive retaliation against his people by the Japanese, who had occupied China’s coastal areas and Manchuria for several years. The Chinese had been slaughtered by the thousands whenever marauding Japanese troops invaded an area. American military personnel in China reported that leaks of classified information were common; we were told that secrecy was almost impossible to maintain in Chiang’s headquarters. As a result, it was decided in Washington that he would not be informed of our plans until we were at sea and the mission could not be recalled.

As we droned on at about 200 feet above the water, Dick Cole and I took turns at the controls. We were all concerned about gas consumption, and everyone on the flight deck was continually checking the gauges against our estimates. A half hour after takeoff we were joined by the second B-25 to depart, which flew a loose formation with us. It was piloted by Lieutenant Travis Hoover. About an hour later, we sighted a camouflaged Japanese ship that we thought might be a light cruiser. About two hours out we flew directly under an enemy flying boat that just loomed at us suddenly out of the mist. We don’t think they saw us. It was heading directly toward the task force.

The weather improved gradually as we got closer to Japan. We changed course briefly several times to avoid various civil and naval-surface craft until we made landfall north of Inubo Shima, about 80 miles north of Tokyo. This was the first time Hank Potter was able to get an accurate fix on our position. Trav Hoover promptly turned off toward his target area.

Since we were somewhat north of our desired course, I decided to take advantage of our position and approach the target area from a northerly direction, thus avoiding anticipated antiaircraft batteries and fighter planes located in the western part of the city. We stayed as low as we could and saw many flying fields interspersed among the beautiful scenery. People on the ground waved at us. There were many planes in the air, mostly small biplanes, apparently trainers.

It was shortly after noon in Tokyo. About 10 miles north of the city we saw nine enemy fighters in three flights of three. Dick Cole kept Paul Leonard advised of the enemy aircraft he could see ahead and at one time counted 80. The fighters didn’t attack us, but flak from antiaircraft ground batteries shook us up a little and might have put a few holes in the fuselage.

When we spotted the large factory buildings in our target area, I pulled up to 1,200 feet and called for bomb doors open. Fred Braemer toggled off the four incendiaries in rapid succession. It was 12:30 P.M. Tokyo time.

I dropped down to rooftop level again and slid over the western outskirts of the city into low haze and smoke, then turned south and out to sea. We saw many barrage balloons over east centra1 Tokyo and passed over a small aircraft factory with a dozen or so completed planes on the flying line. Unfortunately, we had no bombs left and I didn’t want anyone to do any strafing with our machine guns. If we had done that and were downed for any reason, we would surely have been dealt with severely by our captors.

As we sped toward the coast, we saw five fighter planes converging on us from above. There were two little hills ahead. I swung very quickly around the hills in an S turn. The fighters turned also, but apparently they didn’t see the second half of my S. The last time I saw them, they were going off in the opposite direction from us.

We stayed low off the coast and Hank Potter plotted a perfect course to Yaku-shima. The ceiling gradually lowered along the route and got down to about 600 feet. We then turned west over the China Sea and encountered a headwind. Hank Potter estimated we would run out of gas about 135 miles from the Chinese coast. We began to make preparations for ditching. I saw sharks basking in the water below and didn’t think ditching among them would be very appealing. Also saw three naval vessels and many small fishing vessels. None of them fired, so they probably didn’t see us.

Fortunately, the Lord was with us. What had been a headwind slowly turned into a tailwind of about 25 miles per hour and eased our minds about ditching. Trav Hoover had followed us nearly all the way to the Chinese coast. However, he left us as the weather deteriorated and it began to get dark. Visibility was reduced drastically by fog and light rain. As we crossed the Chinese coast, I went on instruments and pulled up to 8,000 feet through the overcast. Our maps showed the mountains to be about 5,000 feet above sea level, but the maps were probably inaccurate. We saw dim lights below occasionally through cloud breaks but had to remain on instruments.

We tried to contact the field at Chuchow on 4495 kilocycles. No answer. This meant that the chance of any of our crews getting to the destination safely was just about nil: Chuchow was situated in a valley about two miles wide and 12 miles long. Without a ground radio station to home in on, there was no way we could find it. All we could do was fly a dead-reckoning course in the direction of Chuchow, abandon ship in midair, and hope that we came down in Chinese-held territory.

When the gas gauges read near zero, I put the B-25 on automatic pilot and told the men in which order to jump: Braemer, Potter, Leonard, and Cole. If we all jumped in a straight line, it would be easier to find one another when we got on the ground. As Dick Cole left, I shut off both gas valves and squeezed quickly after him through the forward hatch. It was about 9:30 P.M. ship time. We had been in the air for 13 hours. We might have had enough fuel left for about another half hour of flight, but the right front tank gauge showed empty, and fuel gauges, even today, are notoriously inaccurate when registering near the zero mark. We had covered about 2,250 miles, mostly at low speed, but about an hour at moderate high speed had more than doubled the consumption during that time.

As I dropped into the rainy darkness, I suddenly realized that I should have put the flaps down before we bailed out. It would have slowed down the landing speed, reduced the impact, and shortened the glide.

This was my third parachute jump to save my hide. It was impossible to see anything below, so all I could do was wait until I hit the ground. My concern as I floated down was about my ankles, which had been broken in South America in 1926. Anticipating a sudden encounter with the ground, I bent my knees to take the shock. When I hit, there wasn’t much impact. I had landed in a rice paddy and fallen into a sitting position in a not-too-fragrant mixture of water and “night soil.”

I stood up, unhurt and thoroughly disgusted with my situation and the smell, unhooked my parachute harness, and looked around. I saw a light and approached what looked like a small farmhouse. I knocked on the door and shouted, “Lushu hoo megwa fugi” (“I am an American”). This was the Chinese phrase we had been taught aboard the carrier by Lieutenant Commander Stephen Jurika, who had served in the Far East before the war. But I must have used the wrong dialect. I heard movement inside, then the sound of a bolt sliding into place. The light went out and there was dead silence.

It was cold and I was shivering. I stumbled on in the darkness and came to a sort of warehouse. Inside, two sawhorses held a large box that was occupied by a very dead Chinese gentleman. It must have been the local morgue. I left and found a water mill, which got me out of the rain, but I was thoroughly chilled. I lay down but couldn’t sleep, so spent most of the night doing light calisthenics to stave off the cold. I stayed there until dawn and then followed a well-worn path toward a small village, where I came upon a Chinese who spoke no English. I drew a picture of a train on a piece of paper. He smiled, nodded, and started off. I followed him to a military headquarters where a Chinese major who spoke a little English gestured for me to hand over my .45-caliber automatic pistol. I refused and explained that I was an American and had parachuted during the night into a rice paddy nearby. He didn’t seem to believe me, so I told him that I would take him to the spot and show him the parachute.

The officer, surrounded by about a dozen armed soldiers, escorted me to the rice paddy where I had landed, but the ‘chute was gone. I said the people in the house must have heard our plane and could verify that I had knocked on their door the night before. However, when the farmer, his wife, and two children were questioned, they denied everything. The major said, “They say they heard no noise during the night. They say they heard no plane. They say they saw no parachute. They say you lie.”

The soldiers started toward me to relieve me of the .45. It was not a comfortable situation. I protested and was saved from having to tussle with them when two soldiers emerged from the house with the parachute. The major smiled and extended his hand in friendship, and I was thus admitted officially to China. He led me back to his headquarters for a warm meal and a much-needed bath. I dried out my uniform but the stench remained intact.

Meanwhile, the major’s men found all four of my crew. It was a relief to see that they were in reasonably good shape. The only minor injury was suffered by Hank Potter, who had sprained an ankle on the bailout.

When the soldiers found our plane, Paul Leonard and I went to the crash site to see what we could salvage. There is no worse sight to an aviator than to see his plane smashed to bits. Ours was spread out over several acres of mountaintop. I fished around the debris for my belongings and found my oil-stained uniform blouse. Some enterprising scavenger had already stripped it of all the brass buttons. There was nothing left of our personal belongings that was worth carrying away.

I sat down beside a wing and looked around at the thousands of pieces of shattered metal that had once been a beautiful airplane. I felt lower than a frog’s posterior. This was my first combat mission. I had planned it from the beginning and led it. I was sure it was my last. As far as I was concerned, it was a failure, and I felt there could be no future for me in uniform now. Even if we had successfully accomplished the first half of our mission, the second half had been to deliver the B-25s to our units in the China-Burma-India theater of operations.

My main concern was for my men. What had happened to my crew probably had happened to the others. If so, they had to be scattered all over a considerable area of China. How many had survived? Had any been taken prisoner by the Japanese? Did any have to ditch in the China Sea?

As I sat there, Paul Leonard took my picture and then, seeing how badly I felt, tried to cheer me up. He asked, “What do you think will happen when you go home, Colonel?”

I answered, “Well, I guess they’ll court-martial me and send me to prison at Fort Leavenworth.”

Paul said, “No, sir. I’ll tell you what will happen. They’re going to make you a general.”

I smiled weakly and he tried again. “And they’re going to give you the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

I smiled again and he made a final effort. “Colonel, I know they’re going to give you another airplane and when they do, I’d like to fly with you as your crew chief.”

It was then that tears came to my eyes. It was the supreme compliment that a mechanic could give a pilot. It meant he was so sure of the skills of the pilot that he would fly anywhere with him under any circumstances. I thanked him and said that if I ever had another airplane and he wanted to be my crew chief, he surely could.

While I deeply appreciated Paul’s supportive remarks, I was sure that when the outcome of this mission was known back home, either I would be court-martialed or the military powers that be would see to it that I would sit out the war flying a desk. I had never felt lower in my life.

The 16-ship Navy task force centered around the aircraft carriers Hornet and Enterprise had been steaming westward toward Japan all night. I had given my final briefing to the B-25 bomber crews on the Hornet the day before. Our job was to do what we could to put a crimp in the Japanese war effort with the 16 tons of bombs from our 16 B-25s. The bombs could do only a fraction of the damage the Japanese had inflicted on us at Pearl Harbor, but the primary purpose of the raid we were about to launch against the main island of Japan was psychological.

The Japanese people had been told they were invulnerable. Their leaders had told them Japan could never be invaded. Proof of this was the fact that Japan had been saved from invasion during the fifteenth century when a massive Chinese fleet set sail to attack Japan and was destroyed by a monsoon. From then on, the Japanese people had firmly believed they were forever protected by a “divine wind” — the kamikaze. An attack on the Japanese homeland would cause confusion in the minds of the Japanese people and sow doubt about the reliability of their leaders.

There was a second, and equally important, psychological reason for this attack. America and its allies had suffered one defeat after another in the Pacific and southern Asia. Besides the devastating surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had taken Wake Island and Guam and had driven American and Filipino forces to surrender on Bataan. Only a small force of Americans was left holding out on the island of Corregidor. America had never seen darker days. Americans badly needed a morale boost. I hoped we could give them that by a retaliatory surprise attack against the enemy’s home islands launched from a carrier, precisely as the Japanese had done at Pearl Harbor. It would be the kind of touché the Japanese military would understand. An air strike would certainly be a blow to their national morale and, furthermore, should cause the Japanese to divert aircraft and equipment from offensive operations to the defense of the home islands.

The basic plan for the raid against Japan was simple. If the Navy task force could get us within 400 to 500 miles of the Japanese coast, the B-25 medium Army bombers aboard the Hornet would launch, with carefully trained crews, against the enemy’s largest cities. Although the carrier’s deck seemed too short to allow the takeoff of a loaded B-25 land-based Army bomber, I was confident it could be done. Two lightly loaded B-25s had made trial takeoffs the previous February from the Hornet off the Virginia coast before the carrier had joined the Pacific fleet. All of the pilots had practiced a number of short-field takeoffs at an auxiliary field near Eglin Field, Florida.

I would take off first so as to arrive over Tokyo at sunset. The other crews would leave the carrier at local sunset and head for their respective targets. I would drop four 50-pound incendiary bombs on a factory area in the center of Tokyo. The resulting fires in the highly inflammable structures in the area would light up the way for the succeeding planes and steer them toward their respective targets in the Tokyo-Yokohama area, Nagoya, and the Kobe-Osaka complex. The rest of the B-25s would be loaded with four 500-pound bombs each — two incendiaries and two demolition bombs. After launching the B-25s, the Navy task force was to retreat immediately and return to Hawaii.

We would not return to the Hornet. After bombing our targets, we were to escape to China. The planes would be turned over to the new Air Force units being formed in the China-Burma-India theater.

There were five crew members in each airplane — pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, and gunner. One crew had a physician aboard — Dr. (Lieutenant) Thomas R. White — who had volunteered and qualified as a gunner so he could go. This was a fortuitous choice, as it turned out, for four members of another crew.

The State Department had tried to get permission from the Soviets for us to land in Soviet territory for refueling. This flight would have been an easy 600 miles or so after bombing the Japanese targets. But permission was denied because the Soviets were neutral vis-à-vis Japan and did not want to have another Axis power at their back door invading their country from that direction.

Therefore, after dropping its bombs, each plane was to head generally southward along the Japanese coast, then westward to Chuchow, located about 70 miles inland and about 200 miles south of Shanghai. After refueling there, we were to proceed to Chungking, 800 miles farther inland. The greatest in-flight distance we would have to fly was 2,000 miles. With the fuel tank modifications we had made and extra gas in five-gallon cans, there was enough fuel on board to fly 2,400 miles, provided the crews used the long-range cruising techniques we had practiced.

Our planes had been positioned on the deck for takeoff the evening before. The mechanics had run up their engines and made last-minute adjustments. I wanted the crews to get a good night’s sleep, but few heeded the advice of an oldster who, at 45, was twice the age of most of them. Some of the officers played poker with the Navy pilots who had been unable to fly since leaving California because our planes took up all the space on the deck. The Navy pilots and our crews wanted to recoup their individual losses before we left.

The Enterprise launched scout planes at daybreak for 200-mile searches, and fighters were sent up as cover for the task force. The weather, which had been moderately rough during the night, worsened. There was a low overcast and visibility was limited. Frequent rain squalls swept over the ships, and the sea began to heave into 30-foot crests. Gusty winds tore off the tops of the waves and blew heavy spray across the ships, drenching the deck crews. At 6:00 A.M., a scout plane returned to the Enterprise and the pilot dropped a bean bag container on the deck with a message saying he had sighted a small enemy fishing vessel and believed he had been seen by the enemy.

Admiral William F. Halsey immediately ordered all ships to swing left to avoid detection. Had the enemy vessel seen the aircraft? No one knew. The question was answered about 7:30 A.M. when another patrol vessel was sighted from the Hornet only 20,000 yards away. A Japanese radio message was intercepted by the Hornet’s radio operator from close by. One of the scout planes then sighted another small vessel 12,000 yards away. A light could be seen bobbing in the rough sea. Halsey ordered the cruiser Nashville to sink it.

Unknown to us, the Japanese had stationed a line of radio-equipped picket boats about 650 nautical miles out from the coast to warn of the approach of American ships. I went to the bridge where Captain Marc A. Mitscher briefed me on what had happened. “It looks like you’re going to have to be on your way soon,” he said. “They know we’re here.” I shook hands with Mitscher and rushed to my cabin to pack, spreading the word as I went.

Some of the B-25 crews had finished breakfast and were lounging in their cabins; others were shaving and getting ready to eat; several may have still been dozing. A few had packed their bags, but I think many were completely surprised because they thought they would not be taking off until late afternoon.

At 8:00 A.M., Admiral Halsey flashed a message to the Hornet: LAUNCH PLANES X TO COL DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU.

The ear-shattering klaxon horn sounded and a booming voice ordered: “Now hear this! Now hear this! Army pilots, man your planes!”

The weather had steadily continued to worsen. The Hornet plunged into mountainous waves that sent water cascading down the deck. Rain pelted us as we ran toward our aircraft. It was not an ideal day for a mission like this one.

The well-disciplined Navy crews and our enlisted men, some of whom had slept on deck near their planes, knew what to do. Slipping and sliding on the wet deck, they ripped off engine and gun turret covers and stuffed them inside the rear hatches. Fuel tanks were topped. The mechanics pulled the props through. Cans of gasoline were filled and handed up to the gunners through the rear hatches. Ropes were unfastened and wheel chocks pu11ed away so the Navy deck handlers could maneuver the B-25s into takeoff position.

Meanwhile, the Hornet picked up speed as best it could in the rough sea and turned into the wind. The 20-knot speed of the carrier and the 30-knot wind blowing directly down the deck meant that we should be airborne safely and quickly. This ability of an aircraft carrier to turn its “airfield” into the wind is a distinct advantage. Rarely do Navy pilots have to worry about cross-wind takeoffs and landings. However, a rough sea such as the one in front of us could ruin a pilot’s day if he ignored the signals of the deck officer and tried a takeoff when the bow of the ship was heading into the waves. It was like riding a seesaw that plunged deep into the water each time the bow dipped downward.

Lieutenant Henry L. “Hank” Miller, the naval officer assigned to us at Eglin Field, Florida, to teach us how to take off in minimum distances, said good-bye to each crew. He told us to watch a blackboard he would be holding up near the ship’s “island” to give us last-minute instructions and the carrier’s heading so our navigators could compare our planes’ compasses with the ship’s heading and set their directional gyros. The navigators were very concerned about our magnetic compasses. After more than two weeks on the carrier, they would be way off calibration, especially on those planes that were tied down close to the carrier’s metal structure. With an overcast sky, the navigators wouldn’t be able to take shots of the sun or stars with their sextants. It would be dead reckoning all the way to the Japanese coast. A check on the accuracy of the compasses was essential.

My crew emerged quickly from their quarters below decks. Sergeant Paul J. Leonard, our crew chief, was one of those skilled mechanics who knew instinctively what to do. Me already had his barracks bag and toolbox stowed in the rear and was helping the deck crews get our ship into takeoff position. In the air, he would be the top turret gunner. During our training at Eglin, he had proven he was a marksman with the twin .50s. Born in 1912, he had dropped out of high school in Roswell, New Mexico, and enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1931, at the start of the Depression. He was one of those rare individuals who applied himself and became one of the most outstanding mechanics with whom I ever served. Men like him were the backbone of the nation’s air service when war began and were highly regarded for their dedication and expertise. They set high standards for the enlisted men who served with them.

Sergeant Fred A. Braemer, of Seattle, Washington, was another “old-timer.” He had joined the infantry in 1935 and transferred to the Air Corps in 1939. He had completed both bombardier and navigator training but was serving on our crew as the bombardier.

Our copilot was Lieutenant Richard E. “Dick” Cole, from Dayton, Ohio, who had completed pilot training in July 1941. Dick was a quietly competent pilot who had attended Ohio University for two years before enlisting as a Flying Cadet. If anything happened to me, I was confident that he would take over the controls of the aircraft and the leadership of the crew without hesitation.

Lieutenant Henry A. “Hank” Potter, of Pierre, South Dakota, was our navigator. Like so many young men in those days, he had also completed two years of college, the minimum for entry into flying training, and had graduated from navigator school in 1941.

I was proud of my crew and all the other volunteers who were willing to lay their lives on the line for a risky mission that I could not tell them about until we were on the carrier. Every man had proven his competence during our training at Eglin. I felt completely comfortable and confident as our B-25 was placed in takeoff position and the wheels chocked.

I knew hundreds of eyes were watching me, especially those of the B-25 crews who were to follow. If I didn’t get off successfully, I’m sure, many thought they wouldn’t be able to make it either. But I knew they would try.

I started the engines, warmed them up, and checked the magnetos. When satisfied, I gave the thumbs-up sign to the deck launching officer holding the checkered flag. As the chocks were pulled, he looked toward the bow and began to wave the flag in circles as a signal for me to push the throttles forward to the stops. At the instant the deck was beginning an upward movement, he gave me the “go” signal and I released the brakes. The B-25 followed the two white guide lines painted on the deck and we were off with feet to spare as the deck reached its maximum pitch.

We left the Hornet at 8:20 A.M. ship time. The carrier’s position was about 824 statute miles from the center of Tokyo. Its position: latitude 35º43’N, longitude 153º25’E.

I signaled Dick for wheels up and as the plane gained flying speed, I leveled off and made a 360-degree turn to come over the carrier. This gave Hank Potter a chance to compare the magnetic heading of the carrier with our compass and align the axis of the carrier with the drift sight. The course of the Hornet was displayed in large figures from the gun turret near the island. Through the use of the airplane’s compass and directional gyro, we were able to set a fairly accurate course for Tokyo.

As we headed toward Japan at low altitude, I thought about how easy the takeoff had been. If everyone followed instructions, they should have no trouble. A night takeoff would have been easy and practicable. That was something I wanted to report to Washington when I got home. It might be useful for future operations.

I began to wonder about the arrangements in China. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, China’s ruler, had not wanted us to land in China after bombing Japan for fear of extensive retaliation against his people by the Japanese, who had occupied China’s coastal areas and Manchuria for several years. The Chinese had been slaughtered by the thousands whenever marauding Japanese troops invaded an area. American military personnel in China reported that leaks of classified information were common; we were told that secrecy was almost impossible to maintain in Chiang’s headquarters. As a result, it was decided in Washington that he would not be informed of our plans until we were at sea and the mission could not be recalled.

As we droned on at about 200 feet above the water, Dick Cole and I took turns at the controls. We were all concerned about gas consumption, and everyone on the flight deck was continually checking the gauges against our estimates. A half hour after takeoff we were joined by the second B-25 to depart, which flew a loose formation with us. It was piloted by Lieutenant Travis Hoover. About an hour later, we sighted a camouflaged Japanese ship that we thought might be a light cruiser. About two hours out we flew directly under an enemy flying boat that just loomed at us suddenly out of the mist. We don’t think they saw us. It was heading directly toward the task force.

The weather improved gradually as we got closer to Japan. We changed course briefly several times to avoid various civil and naval-surface craft until we made landfall north of Inubo Shima, about 80 miles north of Tokyo. This was the first time Hank Potter was able to get an accurate fix on our position. Trav Hoover promptly turned off toward his target area.

Since we were somewhat north of our desired course, I decided to take advantage of our position and approach the target area from a northerly direction, thus avoiding anticipated antiaircraft batteries and fighter planes located in the western part of the city. We stayed as low as we could and saw many flying fields interspersed among the beautiful scenery. People on the ground waved at us. There were many planes in the air, mostly small biplanes, apparently trainers.

It was shortly after noon in Tokyo. About 10 miles north of the city we saw nine enemy fighters in three flights of three. Dick Cole kept Paul Leonard advised of the enemy aircraft he could see ahead and at one time counted 80. The fighters didn’t attack us, but flak from antiaircraft ground batteries shook us up a little and might have put a few holes in the fuselage.

When we spotted the large factory buildings in our target area, I pulled up to 1,200 feet and called for bomb doors open. Fred Braemer toggled off the four incendiaries in rapid succession. It was 12:30 P.M. Tokyo time.

I dropped down to rooftop level again and slid over the western outskirts of the city into low haze and smoke, then turned south and out to sea. We saw many barrage balloons over east centra1 Tokyo and passed over a small aircraft factory with a dozen or so completed planes on the flying line. Unfortunately, we had no bombs left and I didn’t want anyone to do any strafing with our machine guns. If we had done that and were downed for any reason, we would surely have been dealt with severely by our captors.

As we sped toward the coast, we saw five fighter planes converging on us from above. There were two little hills ahead. I swung very quickly around the hills in an S turn. The fighters turned also, but apparently they didn’t see the second half of my S. The last time I saw them, they were going off in the opposite direction from us.

We stayed low off the coast and Hank Potter plotted a perfect course to Yaku-shima. The ceiling gradually lowered along the route and got down to about 600 feet. We then turned west over the China Sea and encountered a headwind. Hank Potter estimated we would run out of gas about 135 miles from the Chinese coast. We began to make preparations for ditching. I saw sharks basking in the water below and didn’t think ditching among them would be very appealing. Also saw three naval vessels and many small fishing vessels. None of them fired, so they probably didn’t see us.

Fortunately, the Lord was with us. What had been a headwind slowly turned into a tailwind of about 25 miles per hour and eased our minds about ditching. Trav Hoover had followed us nearly all the way to the Chinese coast. However, he left us as the weather deteriorated and it began to get dark. Visibility was reduced drastically by fog and light rain. As we crossed the Chinese coast, I went on instruments and pulled up to 8,000 feet through the overcast. Our maps showed the mountains to be about 5,000 feet above sea level, but the maps were probably inaccurate. We saw dim lights below occasionally through cloud breaks but had to remain on instruments.

We tried to contact the field at Chuchow on 4495 kilocycles. No answer. This meant that the chance of any of our crews getting to the destination safely was just about nil: Chuchow was situated in a valley about two miles wide and 12 miles long. Without a ground radio station to home in on, there was no way we could find it. All we could do was fly a dead-reckoning course in the direction of Chuchow, abandon ship in midair, and hope that we came down in Chinese-held territory.

When the gas gauges read near zero, I put the B-25 on automatic pilot and told the men in which order to jump: Braemer, Potter, Leonard, and Cole. If we all jumped in a straight line, it would be easier to find one another when we got on the ground. As Dick Cole left, I shut off both gas valves and squeezed quickly after him through the forward hatch. It was about 9:30 P.M. ship time. We had been in the air for 13 hours. We might have had enough fuel left for about another half hour of flight, but the right front tank gauge showed empty, and fuel gauges, even today, are notoriously inaccurate when registering near the zero mark. We had covered about 2,250 miles, mostly at low speed, but about an hour at moderate high speed had more than doubled the consumption during that time.

As I dropped into the rainy darkness, I suddenly realized that I should have put the flaps down before we bailed out. It would have slowed down the landing speed, reduced the impact, and shortened the glide.

This was my third parachute jump to save my hide. It was impossible to see anything below, so all I could do was wait until I hit the ground. My concern as I floated down was about my ankles, which had been broken in South America in 1926. Anticipating a sudden encounter with the ground, I bent my knees to take the shock. When I hit, there wasn’t much impact. I had landed in a rice paddy and fallen into a sitting position in a not-too-fragrant mixture of water and “night soil.”

I stood up, unhurt and thoroughly disgusted with my situation and the smell, unhooked my parachute harness, and looked around. I saw a light and approached what looked like a small farmhouse. I knocked on the door and shouted, “Lushu hoo megwa fugi” (“I am an American”). This was the Chinese phrase we had been taught aboard the carrier by Lieutenant Commander Stephen Jurika, who had served in the Far East before the war. But I must have used the wrong dialect. I heard movement inside, then the sound of a bolt sliding into place. The light went out and there was dead silence.

It was cold and I was shivering. I stumbled on in the darkness and came to a sort of warehouse. Inside, two sawhorses held a large box that was occupied by a very dead Chinese gentleman. It must have been the local morgue. I left and found a water mill, which got me out of the rain, but I was thoroughly chilled. I lay down but couldn’t sleep, so spent most of the night doing light calisthenics to stave off the cold. I stayed there until dawn and then followed a well-worn path toward a small village, where I came upon a Chinese who spoke no English. I drew a picture of a train on a piece of paper. He smiled, nodded, and started off. I followed him to a military headquarters where a Chinese major who spoke a little English gestured for me to hand over my .45-caliber automatic pistol. I refused and explained that I was an American and had parachuted during the night into a rice paddy nearby. He didn’t seem to believe me, so I told him that I would take him to the spot and show him the parachute.

The officer, surrounded by about a dozen armed soldiers, escorted me to the rice paddy where I had landed, but the ‘chute was gone. I said the people in the house must have heard our plane and could verify that I had knocked on their door the night before. However, when the farmer, his wife, and two children were questioned, they denied everything. The major said, “They say they heard no noise during the night. They say they heard no plane. They say they saw no parachute. They say you lie.”

The soldiers started toward me to relieve me of the .45. It was not a comfortable situation. I protested and was saved from having to tussle with them when two soldiers emerged from the house with the parachute. The major smiled and extended his hand in friendship, and I was thus admitted officially to China. He led me back to his headquarters for a warm meal and a much-needed bath. I dried out my uniform but the stench remained intact.

Meanwhile, the major’s men found all four of my crew. It was a relief to see that they were in reasonably good shape. The only minor injury was suffered by Hank Potter, who had sprained an ankle on the bailout.

When the soldiers found our plane, Paul Leonard and I went to the crash site to see what we could salvage. There is no worse sight to an aviator than to see his plane smashed to bits. Ours was spread out over several acres of mountaintop. I fished around the debris for my belongings and found my oil-stained uniform blouse. Some enterprising scavenger had already stripped it of all the brass buttons. There was nothing left of our personal belongings that was worth carrying away.

I sat down beside a wing and looked around at the thousands of pieces of shattered metal that had once been a beautiful airplane. I felt lower than a frog’s posterior. This was my first combat mission. I had planned it from the beginning and led it. I was sure it was my last. As far as I was concerned, it was a failure, and I felt there could be no future for me in uniform now. Even if we had successfully accomplished the first half of our mission, the second half had been to deliver the B-25s to our units in the China-Burma-India theater of operations.

My main concern was for my men. What had happened to my crew probably had happened to the others. If so, they had to be scattered all over a considerable area of China. How many had survived? Had any been taken prisoner by the Japanese? Did any have to ditch in the China Sea?

As I sat there, Paul Leonard took my picture and then, seeing how badly I felt, tried to cheer me up. He asked, “What do you think will happen when you go home, Colonel?”

I answered, “Well, I guess they’ll court-martial me and send me to prison at Fort Leavenworth.”

Paul said, “No, sir. I’ll tell you what will happen. They’re going to make you a general.”

I smiled weakly and he tried again. “And they’re going to give you the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

I smiled again and he made a final effort. “Colonel, I know they’re going to give you another airplane and when they do, I’d like to fly with you as your crew chief.”

It was then that tears came to my eyes. It was the supreme compliment that a mechanic could give a pilot. It meant he was so sure of the skills of the pilot that he would fly anywhere with him under any circumstances. I thanked him and said that if I ever had another airplane and he wanted to be my crew chief, he surely could.

While I deeply appreciated Paul’s supportive remarks, I was sure that when the outcome of this mission was known back home, either I would be court-martialed or the military powers that be would see to it that I would sit out the war flying a desk. I had never felt lower in my life.