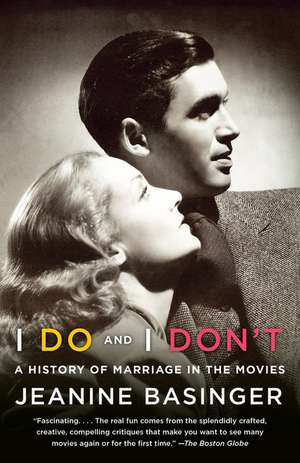

I Do and I Don't: A History of Marriage in the Movies

Autor Jeanine Basingeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 mar 2014

As long as there have been feature movies there have been marriage movies, and yet Hollywood has always been cautious about how to label them—perhaps because, unlike any other genre of film, the marriage movie resonates directly with the experience of almost every adult coming to see it. Here is “happily ever after”—except when things aren't happy, and when “ever after” is abruptly terminated by divorce, tragedy . . . or even murder. With her large-hearted understanding of how movies—and audiences—work, Jeanine Basinger traces the many ways Hollywood has tussled with this tricky subject, explicating the relationships of countless marriages from Blondie and Dagwood to the heartrending couple in the Iranian A Separation, from Tracy and Hepburn to Laurel and Hardy (a marriage if ever there was one) to Coach and his wife in Friday Night Lights.

A treasure trove of insight and sympathy, illustrated with scores of wonderfully telling movie stills, posters, and ads.

Preț: 114.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.87€ • 22.88$ • 18.17£

21.87€ • 22.88$ • 18.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780804169745

ISBN-10: 0804169748

Pagini: 395

Ilustrații: 139 PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 207 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0804169748

Pagini: 395

Ilustrații: 139 PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 207 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Jeanine Basinger is the chair of film studies at Wesleyan University and the curator of the cinema archives there. She has written nine other books on film, including A Woman’s View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930ߝ1960; Silent Stars, winner of the William K. Everson Film History Award; Anthony Mann; The World War II Combat Film: Anatomy of a Genre; and American Cinema: One Hundred Years of Filmmaking, the companion book for a ten-part PBS series.

Extras

Part 1

In the silent-film era, movies told the story of marriage straightforwardly, as a familiar situation—and audiences cheerfully accepted it as such. The idea that marriage might be unappealing at the box office, or perhaps a depressing plot development, didn’t seem to exist in the same way it did later, in the studio-system years. Silent-film makers presented marriage as something audiences could and would recognize, and therefore enjoy seeing on the screen. In embracing the subject, they had available current history, past history, imaginary history . . . different tones, attitudes, moods . . . myriad events and characters . . . the works. Although it was a rigid or fixed social event, marriage could still be used flexibly. It could be the main event, the comic relief, or the tragic subplot. And, of course, it could always be linked to the surefire box-office concept of love.

Unlike in later decades, many silent movies openly carried the concept in the title: The Marriage of William Ashe (1921); The Marriage Maker (1921); Man, Woman, Marriage (1921); The Marriage Chance (1922); Married People (1922); The Married Flapper (1922); The Marriage Market (1923); Marriage Morals (1923); The Marriage Cheat (1924); Marry in Haste (1924); Married Flirts (1924); The Marriage Circle (1924); Marriage in Transit (1925); Marry Me (1925); The Marriage Whirl (1925); Married? (1926); Marriage License (1926); The Marriage Clause (1926); Marriage (1927); Married Alive (1927); Marriage by Contract (1928); Marry the Poor Girl (1928); The Marriage Playground (1929); and Married in Hollywood (1929); etc. And this doesn’t include titles with the words “bride,” “groom,” “wife,” and “husband.”

The marriage film found its basic definition in the silent era, and had no trouble doing so. Why would it? All anyone had to do to tell a story about marriage was to present a couple in love, get them married in the first scene (or open with them already married), set them up in a home of some sort, give them a recognizable problem, make the problem worse, and then resolve it. Couple, situation, problem, resolution: this is the pattern silent audiences saw and embraced, and their responses to it were clear. They would laugh at it. Or they would cry over it. Silent films were a beautiful art, and they were never simpleminded, but many of them often presented marriage in a basic mode, happy or sad. They went bipolar: raucous comedy or stark tragedy.

Both types could be shaped into cautionary tales. The comedy version provided audiences with release as they laughed at their own problem in a safe form, and the tragic one warned them things could be much, much worse. In other words, the pattern for stories about marriages was simple enough: Was it going to be a yes or a no version? Was it “I do” or “I don’t”? Would it divert or warn?

This “bipolar” approach to the basic setup (couple, wedding, home, problems) was a useful business discovery. It was one thing to treat marriage as a joke—that was predictable. The really significant thing was to accept it as a failed enterprise. Once it became clear that viewers had no trouble accepting the idea that marriages could turn into problems, that romance could fail, movies could show marriage as a disappointment without offending married couples. Up there on the screen, marriage didn’t have to be sacred. Entering a movie theater apparently was an absolution. Long before they had arrived in their seats, boy had met girl, boy had got girl, and boy had married girl. That part was over, and they apparently felt it was now okay for all hell to break loose on the screen. Nosy neighbors, hideous in-laws, naughty children, snotty and ungrateful children, interfering children, lost children, kidnapped children, crippled children, evil children. Uppity cooks, oversexed maids, lippy gardeners, and butlers with more class than their employers, because, lord knows, you just couldn’t get good help. Adultery, competition, bankruptcy, arson, death, murder, and suicide. Incest. War and plague. Earthquakes and typhoons and a household of terrible furniture never fully paid for. Marriage on film could be a world of woe, all the direct result of merely saying two words: “I do.” Marriage could be—and was—accepted as a hangover, the “after” of the happily-ever-after.

The hilarious comedy version was common in two-reelers, where lampooning marriage had great appeal for audiences. For filmmakers, it was an easy shorthand with which to connect to what men and women knew—and get them to laugh about it. In particular, Mack Sennett comedy shorts made use of marital conflicts between two incompatible mates. (Bring on the rolling pin and the mother-in-law jokes!) The mockery of marriage liberated everybody—audiences, who roared at what they recognized, and moviemakers, who rolled freely over its sacredness in all directions. Two great examples from Sennett star the wonderful team of Fatty Arbuckle and Mabel Normand, talented clowns of the silent era. In 1915, Fatty and Mabel made two gems, That Little Band of Gold and Fatty and Mabel’s Married Life. In the former, an entire romantic comedy is neatly wrapped up with one single title card: “A Kiss, A Pledge, A Ring.” (So much for the meet-cute.) Immediately following, after the marriage, trouble arrives. Another title card says it all: “And now she waits for him.” A few frames later, she’s being told “Your husband is sipping wine with a strange woman”—and suddenly it’s “all over but the alimony.” Mabel’s mother is very helpful in this brief but eloquent scenario. With no need for a title card, she is seen clearly mouthing the traditional words “I told you so” to Mabel when Fatty begins to misbehave.

Fatty and Mabel’s Married Life, a self-labeled “farce comedy,” lays out what would always be a typical conflict in movies about marriage: the man goes out to work, and the woman is left home alone. When he comes back at night, he sits and smokes his cigar, and she has nothing to do but sew. Progress in their relationship is depicted by Mabel getting mad and throwing things and by Fatty falling down a lot. In the end, the police arrive and the neighbors are shocked. Crammed into the brief two reels of running time are such further developments as kisses and promises, mistakes and misunderstandings, apologies and accusations, tears and laughter—not to mention some gunfire, an organ grinder, and a monkey. All these things are pretty much what will become the basic elements of the marriage movies of the future, only with more gunfire and no organ grinder. (The monkey stays in the picture.)

Even comics such as Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, who created their own specific and original universes on film, used wretched marital behavior as basic material. In Spite Marriage (1929) Keaton becomes the victim of a sophisticated stage actress (Dorothy Sebastian) who marries him only after she’s been jilted, hence the film’s title. Keaton, a pants presser by trade, is then stuck with a tantrum-throwing bride who gets dead drunk on their wedding night and creates an awful scene in a nightclub. In My Wife’s Relations (1922), Keaton is yoked to an unloving Polish wife who has four huge and horrible brothers who constantly torment him physically and mentally and, despite everything, hilariously. Keaton is, in fact, a kind of house slave. Things change when the brothers mistakenly think Keaton’s inherited a fortune. “He’s rich,” one grouses. “Now we’ll have to be nice to him.” Another brother is more cerebral: “Let’s murder him first and then kill him.” When it came to marriage, Keaton’s character was snakebit. He and his new bride are happy in One Week (1920), but when they try to work together and assemble their prefab little house, nothing goes right.

Harold Lloyd made a charming two-reeler called I Do in 1921, in which he and his beloved surreptitiously elope, never realizing that her parents, who are dying to get them married, are facilitating their sneaky actions all the way. Lloyd’s best film about marriage is feature-length: Hot Water (1924). As the movie begins, the audience is treated to the following title card:

Married life is like dandruff—it falls heavily upon your shoulders—you get a lot of free advice about it—but up to date nothing has been found to cure it.

As the plot gets under way, Lloyd’s character says no matter what he’ll never exchange his freedom for marriage, but bang! He spots the lovely Jobyna Ralson, and his life is suddenly defined as: “A honeymoon—then rent to pay.” Lloyd has to support not only his wife but also her hideous family: a lazy lout of an older brother, a Dennis-the-Menace younger one (an artist with a pea shooter), and one of film’s most horrific mothers-in-law, played by Josephine Crowell. Crowell is described as having “the nerve of a book agent, the disposition of a dyspeptic landlord, and the heart of a traffic cop.” (And what’s more, she sleepwalks.) Lloyd earns a living for the sponging brood, runs their errands, puts up with their insults, and endures comic interludes that include his struggle to bring a live turkey home on a crowded streetcar as well as a terrifying ride with the family in his new automobile (“the Butterfly Six”). With help from his in-laws, the car is totaled.

The Keaton and Lloyd films are very funny, but if you described the events happening onscreen to a blind man, he’d probably weep. Most silent comedy presented marriage as hell. What made it work was that although the movies were saying “marriage is a disaster,” they were also winking and adding, “but it’s our disaster.” The comedy was empathic. It touched on issues that plagued ordinary people—in-laws, money, infidelity, misunderstandings—and exaggerated them into comic excess. There was a jaunty quality to the horror, an almost jolly sense of shared entrapment, with an underlying agreement that it may have happened to you, but it’s happened to all of us. The slapstick marriage comedy of the silent era had camaraderie on sale, and audiences bought it happily.

The wonderful thing about such rollicking cartoons was that although they were about marriage, you didn’t have to be married to enjoy them. They were just funny, with a wide appeal. Inside the brief twenty minutes of comic chaos was a solid honesty: kitchens, sofas, rocking chairs, dining tables, and bedrooms. Ordinary things such as furniture and mealtimes were juxtaposed with exaggerated details and unexpected twists. Marriage was marriage, with its daily routines, but added to it would be a round of burglaries, a monstrous mother-in-law, a set of misunderstandings, a matched pair of incompatible desires (he wants to smoke and read, she wants some excitement), and hand-to-hand combat with rolling pins, humidors, and frying pans—and a monkey. It was the marriage film made both comic and active, a marriage on its feet, up and running.

The cautionary-tale approach became the most typical of the marriage-movie plots. It could warn about any sort of topical problem; it maintained current morality; and it provided an opportunity to get around censorship or prudery by punishing whatever sin it decided to depict. Best of all, it reassured audiences. It showed them their troubles, but put them to rights. Its canny pattern of establishing normalcy (and proper values), following with a visual depiction of sinful behavior (pushed as far as the movies dared to go), and concluding with a restoration of the original family values, became the golden mean of marriage movies.

An example of the cautionary tale as a high-stakes drama is Cecil B. DeMille’s 1915 version of The Cheat, starring Fannie Ward and Sessue Hayakawa. The Cheat teaches audiences that there is passion out there, and danger, and delicious exotic “otherness”—but suggests they should experience it only at the movies, for the sake of their own flesh and the safety of their families. The Cheat’s social-butterfly wife is the treasurer of a charity, and when she wants to buy some expensive clothes she can’t afford, she uses the charity’s money to gamble on Wall Street. She loses. Unwilling to admit her indiscretion to her straitlaced husband, she accepts a loan from a “rich Oriental” (Hayakawa) in return for her “affections.” Her husband then unexpectedly (and conveniently) earns the same sum of money on his own, more successful speculations and gives it to his wife to spend as she wishes. When she happily takes the money to Hayakawa to cancel their arrangement, he calls her a “cheat.” To make his point, he spectacularly burns his brand on her naked shoulder, marking her as his property because he “bought” her. She then does what a silent-film woman is supposed to do: she shoots him. Unfortunately, her husband shows up and is arrested for the crime.

This tale of a cheating wife whose flesh gets burned is beyond cautionary. It is an outright warning, and it’s far more effective than it sounds. (A brief plot description cannot do full justice to the movie.) Hayakawa is exotic, and overtly presented as a sexually exciting Asian male. (He was reviewed in Variety as “the best Japanese heavy man that has been utilized in this fashion.”) The movie suggests that whereas the wife’s misuse of funds is unacceptably naughty indeed, her sexual excitement is thoroughly understandable. She’s a bored woman wed to a husband Variety describes as “one of the milk and water sop sort of husbands who really doesn’t know enough to assert himself as master of his own ménage.” Their marriage is correctly upper-class, but dull. The “loan” and the “arrangement” are alluring—hot stuff for the times—and anyone can understand why the wife falls under the almost hypnotic control of her exotic lover. DeMille’s use of editing to connect his lovers across time and space, as well as for the presentation of a sense of psychological space, is considered an important moment in his career as well as in the development of film language.

Audiences embraced The Cheat. It was a cautionary tale that struck close to home. Flesh branding they may not have experienced, but dull husbands they knew. The Cheat was so popular that it was remade twice, in 1923 with Pola Negri and in 1931 with Tallulah Bankhead. Since the audience knew what was required by the rules of marriage, the same basic story could be repeated with slight adjustments to reflect changing morality. In the 1923 version, Pola Negri’s would-be lover was no longer Asian, only a “fake Hindu prince.” The racial elements were totally abandoned. In 1931, Bankhead merely got a scoundrel, played by the lackluster Irving Pichel. Instead of being from an exotic culture, Pichel was “just back from the Orient,” a traveler to mysterious areas, rather than a mystery. What was directly connected to an audience’s sense of morality and racism in 1915 had been toned down in 1923. By 1931, the film openly treated the material as dated, as if women were branded weekly around the old small-town campfire. (Variety said, “Something of an ancient complexion clings to the story.”) The villain no longer has the power to hypnotize a naïve wife into submission—he just chases her around some cavernous sets as if he were trying to get a prom date. (With Bankhead playing her, who was to believe in her innocent inexperience?) And yet the film did well, because its fundamental excitement lay in a wife daring to be unfaithful but learning her lesson—which was a lesson for everyone. Some things went out of style, but caution was always smart.

In the silent-film era, movies told the story of marriage straightforwardly, as a familiar situation—and audiences cheerfully accepted it as such. The idea that marriage might be unappealing at the box office, or perhaps a depressing plot development, didn’t seem to exist in the same way it did later, in the studio-system years. Silent-film makers presented marriage as something audiences could and would recognize, and therefore enjoy seeing on the screen. In embracing the subject, they had available current history, past history, imaginary history . . . different tones, attitudes, moods . . . myriad events and characters . . . the works. Although it was a rigid or fixed social event, marriage could still be used flexibly. It could be the main event, the comic relief, or the tragic subplot. And, of course, it could always be linked to the surefire box-office concept of love.

Unlike in later decades, many silent movies openly carried the concept in the title: The Marriage of William Ashe (1921); The Marriage Maker (1921); Man, Woman, Marriage (1921); The Marriage Chance (1922); Married People (1922); The Married Flapper (1922); The Marriage Market (1923); Marriage Morals (1923); The Marriage Cheat (1924); Marry in Haste (1924); Married Flirts (1924); The Marriage Circle (1924); Marriage in Transit (1925); Marry Me (1925); The Marriage Whirl (1925); Married? (1926); Marriage License (1926); The Marriage Clause (1926); Marriage (1927); Married Alive (1927); Marriage by Contract (1928); Marry the Poor Girl (1928); The Marriage Playground (1929); and Married in Hollywood (1929); etc. And this doesn’t include titles with the words “bride,” “groom,” “wife,” and “husband.”

The marriage film found its basic definition in the silent era, and had no trouble doing so. Why would it? All anyone had to do to tell a story about marriage was to present a couple in love, get them married in the first scene (or open with them already married), set them up in a home of some sort, give them a recognizable problem, make the problem worse, and then resolve it. Couple, situation, problem, resolution: this is the pattern silent audiences saw and embraced, and their responses to it were clear. They would laugh at it. Or they would cry over it. Silent films were a beautiful art, and they were never simpleminded, but many of them often presented marriage in a basic mode, happy or sad. They went bipolar: raucous comedy or stark tragedy.

Both types could be shaped into cautionary tales. The comedy version provided audiences with release as they laughed at their own problem in a safe form, and the tragic one warned them things could be much, much worse. In other words, the pattern for stories about marriages was simple enough: Was it going to be a yes or a no version? Was it “I do” or “I don’t”? Would it divert or warn?

This “bipolar” approach to the basic setup (couple, wedding, home, problems) was a useful business discovery. It was one thing to treat marriage as a joke—that was predictable. The really significant thing was to accept it as a failed enterprise. Once it became clear that viewers had no trouble accepting the idea that marriages could turn into problems, that romance could fail, movies could show marriage as a disappointment without offending married couples. Up there on the screen, marriage didn’t have to be sacred. Entering a movie theater apparently was an absolution. Long before they had arrived in their seats, boy had met girl, boy had got girl, and boy had married girl. That part was over, and they apparently felt it was now okay for all hell to break loose on the screen. Nosy neighbors, hideous in-laws, naughty children, snotty and ungrateful children, interfering children, lost children, kidnapped children, crippled children, evil children. Uppity cooks, oversexed maids, lippy gardeners, and butlers with more class than their employers, because, lord knows, you just couldn’t get good help. Adultery, competition, bankruptcy, arson, death, murder, and suicide. Incest. War and plague. Earthquakes and typhoons and a household of terrible furniture never fully paid for. Marriage on film could be a world of woe, all the direct result of merely saying two words: “I do.” Marriage could be—and was—accepted as a hangover, the “after” of the happily-ever-after.

The hilarious comedy version was common in two-reelers, where lampooning marriage had great appeal for audiences. For filmmakers, it was an easy shorthand with which to connect to what men and women knew—and get them to laugh about it. In particular, Mack Sennett comedy shorts made use of marital conflicts between two incompatible mates. (Bring on the rolling pin and the mother-in-law jokes!) The mockery of marriage liberated everybody—audiences, who roared at what they recognized, and moviemakers, who rolled freely over its sacredness in all directions. Two great examples from Sennett star the wonderful team of Fatty Arbuckle and Mabel Normand, talented clowns of the silent era. In 1915, Fatty and Mabel made two gems, That Little Band of Gold and Fatty and Mabel’s Married Life. In the former, an entire romantic comedy is neatly wrapped up with one single title card: “A Kiss, A Pledge, A Ring.” (So much for the meet-cute.) Immediately following, after the marriage, trouble arrives. Another title card says it all: “And now she waits for him.” A few frames later, she’s being told “Your husband is sipping wine with a strange woman”—and suddenly it’s “all over but the alimony.” Mabel’s mother is very helpful in this brief but eloquent scenario. With no need for a title card, she is seen clearly mouthing the traditional words “I told you so” to Mabel when Fatty begins to misbehave.

Fatty and Mabel’s Married Life, a self-labeled “farce comedy,” lays out what would always be a typical conflict in movies about marriage: the man goes out to work, and the woman is left home alone. When he comes back at night, he sits and smokes his cigar, and she has nothing to do but sew. Progress in their relationship is depicted by Mabel getting mad and throwing things and by Fatty falling down a lot. In the end, the police arrive and the neighbors are shocked. Crammed into the brief two reels of running time are such further developments as kisses and promises, mistakes and misunderstandings, apologies and accusations, tears and laughter—not to mention some gunfire, an organ grinder, and a monkey. All these things are pretty much what will become the basic elements of the marriage movies of the future, only with more gunfire and no organ grinder. (The monkey stays in the picture.)

Even comics such as Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, who created their own specific and original universes on film, used wretched marital behavior as basic material. In Spite Marriage (1929) Keaton becomes the victim of a sophisticated stage actress (Dorothy Sebastian) who marries him only after she’s been jilted, hence the film’s title. Keaton, a pants presser by trade, is then stuck with a tantrum-throwing bride who gets dead drunk on their wedding night and creates an awful scene in a nightclub. In My Wife’s Relations (1922), Keaton is yoked to an unloving Polish wife who has four huge and horrible brothers who constantly torment him physically and mentally and, despite everything, hilariously. Keaton is, in fact, a kind of house slave. Things change when the brothers mistakenly think Keaton’s inherited a fortune. “He’s rich,” one grouses. “Now we’ll have to be nice to him.” Another brother is more cerebral: “Let’s murder him first and then kill him.” When it came to marriage, Keaton’s character was snakebit. He and his new bride are happy in One Week (1920), but when they try to work together and assemble their prefab little house, nothing goes right.

Harold Lloyd made a charming two-reeler called I Do in 1921, in which he and his beloved surreptitiously elope, never realizing that her parents, who are dying to get them married, are facilitating their sneaky actions all the way. Lloyd’s best film about marriage is feature-length: Hot Water (1924). As the movie begins, the audience is treated to the following title card:

Married life is like dandruff—it falls heavily upon your shoulders—you get a lot of free advice about it—but up to date nothing has been found to cure it.

As the plot gets under way, Lloyd’s character says no matter what he’ll never exchange his freedom for marriage, but bang! He spots the lovely Jobyna Ralson, and his life is suddenly defined as: “A honeymoon—then rent to pay.” Lloyd has to support not only his wife but also her hideous family: a lazy lout of an older brother, a Dennis-the-Menace younger one (an artist with a pea shooter), and one of film’s most horrific mothers-in-law, played by Josephine Crowell. Crowell is described as having “the nerve of a book agent, the disposition of a dyspeptic landlord, and the heart of a traffic cop.” (And what’s more, she sleepwalks.) Lloyd earns a living for the sponging brood, runs their errands, puts up with their insults, and endures comic interludes that include his struggle to bring a live turkey home on a crowded streetcar as well as a terrifying ride with the family in his new automobile (“the Butterfly Six”). With help from his in-laws, the car is totaled.

The Keaton and Lloyd films are very funny, but if you described the events happening onscreen to a blind man, he’d probably weep. Most silent comedy presented marriage as hell. What made it work was that although the movies were saying “marriage is a disaster,” they were also winking and adding, “but it’s our disaster.” The comedy was empathic. It touched on issues that plagued ordinary people—in-laws, money, infidelity, misunderstandings—and exaggerated them into comic excess. There was a jaunty quality to the horror, an almost jolly sense of shared entrapment, with an underlying agreement that it may have happened to you, but it’s happened to all of us. The slapstick marriage comedy of the silent era had camaraderie on sale, and audiences bought it happily.

The wonderful thing about such rollicking cartoons was that although they were about marriage, you didn’t have to be married to enjoy them. They were just funny, with a wide appeal. Inside the brief twenty minutes of comic chaos was a solid honesty: kitchens, sofas, rocking chairs, dining tables, and bedrooms. Ordinary things such as furniture and mealtimes were juxtaposed with exaggerated details and unexpected twists. Marriage was marriage, with its daily routines, but added to it would be a round of burglaries, a monstrous mother-in-law, a set of misunderstandings, a matched pair of incompatible desires (he wants to smoke and read, she wants some excitement), and hand-to-hand combat with rolling pins, humidors, and frying pans—and a monkey. It was the marriage film made both comic and active, a marriage on its feet, up and running.

The cautionary-tale approach became the most typical of the marriage-movie plots. It could warn about any sort of topical problem; it maintained current morality; and it provided an opportunity to get around censorship or prudery by punishing whatever sin it decided to depict. Best of all, it reassured audiences. It showed them their troubles, but put them to rights. Its canny pattern of establishing normalcy (and proper values), following with a visual depiction of sinful behavior (pushed as far as the movies dared to go), and concluding with a restoration of the original family values, became the golden mean of marriage movies.

An example of the cautionary tale as a high-stakes drama is Cecil B. DeMille’s 1915 version of The Cheat, starring Fannie Ward and Sessue Hayakawa. The Cheat teaches audiences that there is passion out there, and danger, and delicious exotic “otherness”—but suggests they should experience it only at the movies, for the sake of their own flesh and the safety of their families. The Cheat’s social-butterfly wife is the treasurer of a charity, and when she wants to buy some expensive clothes she can’t afford, she uses the charity’s money to gamble on Wall Street. She loses. Unwilling to admit her indiscretion to her straitlaced husband, she accepts a loan from a “rich Oriental” (Hayakawa) in return for her “affections.” Her husband then unexpectedly (and conveniently) earns the same sum of money on his own, more successful speculations and gives it to his wife to spend as she wishes. When she happily takes the money to Hayakawa to cancel their arrangement, he calls her a “cheat.” To make his point, he spectacularly burns his brand on her naked shoulder, marking her as his property because he “bought” her. She then does what a silent-film woman is supposed to do: she shoots him. Unfortunately, her husband shows up and is arrested for the crime.

This tale of a cheating wife whose flesh gets burned is beyond cautionary. It is an outright warning, and it’s far more effective than it sounds. (A brief plot description cannot do full justice to the movie.) Hayakawa is exotic, and overtly presented as a sexually exciting Asian male. (He was reviewed in Variety as “the best Japanese heavy man that has been utilized in this fashion.”) The movie suggests that whereas the wife’s misuse of funds is unacceptably naughty indeed, her sexual excitement is thoroughly understandable. She’s a bored woman wed to a husband Variety describes as “one of the milk and water sop sort of husbands who really doesn’t know enough to assert himself as master of his own ménage.” Their marriage is correctly upper-class, but dull. The “loan” and the “arrangement” are alluring—hot stuff for the times—and anyone can understand why the wife falls under the almost hypnotic control of her exotic lover. DeMille’s use of editing to connect his lovers across time and space, as well as for the presentation of a sense of psychological space, is considered an important moment in his career as well as in the development of film language.

Audiences embraced The Cheat. It was a cautionary tale that struck close to home. Flesh branding they may not have experienced, but dull husbands they knew. The Cheat was so popular that it was remade twice, in 1923 with Pola Negri and in 1931 with Tallulah Bankhead. Since the audience knew what was required by the rules of marriage, the same basic story could be repeated with slight adjustments to reflect changing morality. In the 1923 version, Pola Negri’s would-be lover was no longer Asian, only a “fake Hindu prince.” The racial elements were totally abandoned. In 1931, Bankhead merely got a scoundrel, played by the lackluster Irving Pichel. Instead of being from an exotic culture, Pichel was “just back from the Orient,” a traveler to mysterious areas, rather than a mystery. What was directly connected to an audience’s sense of morality and racism in 1915 had been toned down in 1923. By 1931, the film openly treated the material as dated, as if women were branded weekly around the old small-town campfire. (Variety said, “Something of an ancient complexion clings to the story.”) The villain no longer has the power to hypnotize a naïve wife into submission—he just chases her around some cavernous sets as if he were trying to get a prom date. (With Bankhead playing her, who was to believe in her innocent inexperience?) And yet the film did well, because its fundamental excitement lay in a wife daring to be unfaithful but learning her lesson—which was a lesson for everyone. Some things went out of style, but caution was always smart.

Recenzii

“A witty look at how films portray marriage, and how these onscreen contradictions mirror the institution itself.”

—O Magazine

“A breezy, fun excursion into Hollywood’s presentation of matrimony . . . deeply personal.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Fascinating . . . The real fun comes from the splendidly crafted, creative, compelling critiques that make you want to see many movies again or for the first time.”

—The Boston Globe

“Written by the esteemed Wesleyan University academic and cinematic soothsayer Jeanine Basinger . . . an insightful account of how films have represented wedlock, both holy and unholy, through the years . . . Basinger has a gift for zeroing in on tantalizing details that bring a visual medium to readable life.”

—USA Today

“Lively . . . knowing and illuminating . . . Hollywood movies of the studio era were not, as Basinger takes pains to point out, produced by naifs. Many of them convey sophisticated references to sexual intercourse, prostitution, even homosexuality—if you know how to interpret them. That some of us still do is often thanks to popular scholars like Basinger . . . hilarious, spot-on.”

—Salon

“[Basinger's] writing is strong, the vision clear . . . the amount of titles discussed and revisited are staggering . . . informative and witty . . . deft.”

—Slant Magazine

“A spikily opinionated voice congenial to a diverse readership: barbed observations for the casual fan and a hog heaven of footnotes for the tenure track cineaste.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Thanks to her impeccable research and thoroughly entertaining prose, Basinger provides a take on matrimony that is never less than fascinating. Nimbly moving through history, she illustrates the lengths to which Hollywood has gone in order to make the institution of marriage exciting enough to attract audiences looking for escapism . . . A riveting lesson in history and pop psychology, one that will appeal to film buffs of just about every stripe, not only those interested in happily ever after.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“[An] entertaining take on how the silver screen has portrayed wedded bliss and wedded misery . . . The main pleasure here is Basinger’s explication of how the movies and stars of the studio system years made all this work . . . fascinating, fact-filled.”

—Kirkus

—O Magazine

“A breezy, fun excursion into Hollywood’s presentation of matrimony . . . deeply personal.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Fascinating . . . The real fun comes from the splendidly crafted, creative, compelling critiques that make you want to see many movies again or for the first time.”

—The Boston Globe

“Written by the esteemed Wesleyan University academic and cinematic soothsayer Jeanine Basinger . . . an insightful account of how films have represented wedlock, both holy and unholy, through the years . . . Basinger has a gift for zeroing in on tantalizing details that bring a visual medium to readable life.”

—USA Today

“Lively . . . knowing and illuminating . . . Hollywood movies of the studio era were not, as Basinger takes pains to point out, produced by naifs. Many of them convey sophisticated references to sexual intercourse, prostitution, even homosexuality—if you know how to interpret them. That some of us still do is often thanks to popular scholars like Basinger . . . hilarious, spot-on.”

—Salon

“[Basinger's] writing is strong, the vision clear . . . the amount of titles discussed and revisited are staggering . . . informative and witty . . . deft.”

—Slant Magazine

“A spikily opinionated voice congenial to a diverse readership: barbed observations for the casual fan and a hog heaven of footnotes for the tenure track cineaste.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Thanks to her impeccable research and thoroughly entertaining prose, Basinger provides a take on matrimony that is never less than fascinating. Nimbly moving through history, she illustrates the lengths to which Hollywood has gone in order to make the institution of marriage exciting enough to attract audiences looking for escapism . . . A riveting lesson in history and pop psychology, one that will appeal to film buffs of just about every stripe, not only those interested in happily ever after.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“[An] entertaining take on how the silver screen has portrayed wedded bliss and wedded misery . . . The main pleasure here is Basinger’s explication of how the movies and stars of the studio system years made all this work . . . fascinating, fact-filled.”

—Kirkus