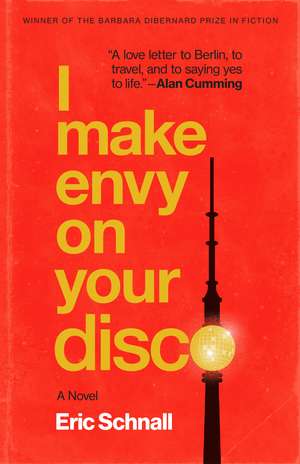

I Make Envy on Your Disco: A Novel: Zero Street Fiction

Autor Eric Schnallen Limba Engleză Paperback – mai 2024

"A funny and moving debut."—Charles Arrowsmith, The Washington Post

“A love letter to Berlin, to travel, and to saying yes to life.”—Alan Cumming

It’s the new millennium and the anxiety of midlife is creeping up on Sam Singer, a thirty-seven-year-old art advisor. Fed up with his partner and his life in New York, Sam flies to Berlin to attend a gallery opening. There he finds a once-divided city facing an identity crisis of its own. In Berlin the past is everywhere: the graffiti-stained streets, the candlelit cafés and techno clubs, the astonishing mash-up of architecture, monuments, and memorials.

A trip that begins in isolation evolves into one of deep connection and possibility. In an intensely concentrated series of days, Sam finds himself awash in the city, stretched in limbo between his own past and future—in nightclubs with Jeremy, a lonely wannabe DJ; navigating a flirtation with Kaspar, an East Berlin artist he meets at a café; and engaged in a budding relationship with Magda, the enigmatic and icy manager of Sam’s hotel, whom Sam finds himself drawn to and determined to thaw. I Make Envy on Your Disco is at once a tribute to Berlin, a novel of longing and connection, and a coming-of-middle-age story about confronting the person you were and becoming the person you want to be.

Preț: 121.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 182

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.24€ • 24.85$ • 19.38£

23.24€ • 24.85$ • 19.38£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Livrare express 13-19 martie pentru 62.52 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496239013

ISBN-10: 1496239016

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Zero Street Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496239016

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Zero Street Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Eric Schnall has worked on and off Broadway as a producer and marketing director for more than twenty-five years. He won a Tony Award for the Broadway revival of Hedwig and the Angry Inch and a Lucille Lortel Award for Fleabag. He has also written about techno and electronic music for Billboard and Revolution, profiling DJs and musicians from around the world.

Extras

Nothing Translates

Everything is a puzzle. The windows open differently here, from the top,

the corners slanting inward. There’s no radio, no clock in the room, yet

the floors in the bathroom are heated by a switch next to the door. To

flush the toilet, I must step on a metal lever. There is no UP or DOWN

button on the panel beside the elevator. Instead, I punch in the number

of the floor I’m going to. I’m on the third floor, but I press 0 to get to

the street. When I ride the train, I buy my ticket from one machine and

get it stamped by another, but no one checks my ticket. I just get on

the train and sit. When the train reaches my stop, I push a button so

the door slides open and I can exit. I’ve forgotten to do this a few times

already and have twice missed my stop. Though I have no use for warm

marble floors, I’ll leave them on for the length of my stay, because they’re

there, I’m paying for them, and they’re controlled by the one button in

Berlin I seem to understand.

Some hotels overlook mountains or the sea. My hotel sits at the end

of a tramline, tucked away on a side street, hidden from the bustle

of Mitte. My room has its own peculiar view: one window faces the

street, its slim glass doors opening to a balcony just big enough to

step outside for a cigarette, if I still smoked. A cluster of yellow trams

sleep below and a maze of wire dangles a few yards from my window,

feeding power to the machines. Across the street, an apartment building

is covered entirely in graffiti, and in big red letters: FUCK BUSH.

And in the distance stands the Fernsehturm, the TV Tower that hovers

over Alexanderplatz like a giant steel dandelion.

The other side of my room overlooks a courtyard. Strands of flowering

vines crawl up walls, defying the October chill. A small koi pond

is lit from below. A few tables and chairs are scattered in the yard, but

it’s hard to imagine they’ve gotten much use. It’s been cold and rainy

since I arrived in Berlin rather suddenly, less than two days ago.

I go down to the breakfast room. A wall of windows faces the courtyard.

German tourists and businessmen sit at square tables eating cake,

salami, and muesli. Outside it’s gray and drizzly and the wind is gusty,

but they all seem used to it. Most of them, like me, have blue eyes.

The hotel is staffed almost entirely by young women dressed in

black. They are all very beautiful. “Guten Morgen,” one says as she leads

me to a table. Her name tag reads Astrid. “Kaffee?” she asks, tilting

her head to the side. I nod. As Astrid pours the coffee, her blond hair

drifts down her shoulder and she sighs, “Soooo . . .” Everyone says this

to me. I eventually discover that it means here you go, but not quite.

Nothing is what it seems here. Nothing translates. The word bitte

means please and you’re welcome and may I help you? When I walk

around the city, streets don’t have names like 14th Street or Avenue

A. My hotel is between Grosse Präsidentenstrasse and Oranienburger

Strasse. That’s two streets and sixteen syllables.

I’ve come to Berlin to see an exhibit at Klaus Beckmann’s Zukunftsgalerie,

curated by the owner himself. The latest show at the “gallery

of the future” is all about the past. Its theme is Ostalgie, the nostalgia

for the products, objects, and way of life that disappeared from the

East almost overnight, after the Wall fell, less than fifteen years ago.

I’m an art advisor in New York. I specialize in contemporary art

and tell people what to buy. Sometimes I consult for corporations,

but mostly I deal with private collectors, which means that these days,

I spend a lot of time with the newly wealthy—hedgefunders,

trophy wives, Europeans, that sort of thing. I often find myself trapped in

their cavernous apartments or strolling arm in arm with them through

galleries in Chelsea, dining out with their families, making small talk,

just hoping to close a sale.

Walking around Mitte, the neighborhood that bridges east and west,

I see graffiti everywhere. But it’s not fuck-you graffiti. It’s beautiful,

the wild bursts of color and ridiculous taglines. Art is everywhere—painted

on buildings, stenciled on doorways, plastered on pipes. It is

raw and, like much of Berlin, reminds me of New York in the seventies

and early eighties, the city of my youth.

I picture Times Square: the crowds, the lights, television screens

and scrolling headlines, the stock quotes, kidnappings, and natural

disasters. Endless information pouring across pixilated walls. It’s the

core of my city now, an advertisement for everything and nothing, the

void filled with a million things.

There’s nothing about Berlin that’s on similar display. It’s a cagey

peacock with its dazzling tail spread, walking away from you while

looking backward. It seems an insular and introspective culture, happy

to be on its own, connected by the dark threads of its knotty history.

Daniel would say that I’ve got it all wrong. A city unfolds, takes its

time. “Sleep,” he’d tell me. Because first impressions are never right.

Everything is a puzzle. The windows open differently here, from the top,

the corners slanting inward. There’s no radio, no clock in the room, yet

the floors in the bathroom are heated by a switch next to the door. To

flush the toilet, I must step on a metal lever. There is no UP or DOWN

button on the panel beside the elevator. Instead, I punch in the number

of the floor I’m going to. I’m on the third floor, but I press 0 to get to

the street. When I ride the train, I buy my ticket from one machine and

get it stamped by another, but no one checks my ticket. I just get on

the train and sit. When the train reaches my stop, I push a button so

the door slides open and I can exit. I’ve forgotten to do this a few times

already and have twice missed my stop. Though I have no use for warm

marble floors, I’ll leave them on for the length of my stay, because they’re

there, I’m paying for them, and they’re controlled by the one button in

Berlin I seem to understand.

Some hotels overlook mountains or the sea. My hotel sits at the end

of a tramline, tucked away on a side street, hidden from the bustle

of Mitte. My room has its own peculiar view: one window faces the

street, its slim glass doors opening to a balcony just big enough to

step outside for a cigarette, if I still smoked. A cluster of yellow trams

sleep below and a maze of wire dangles a few yards from my window,

feeding power to the machines. Across the street, an apartment building

is covered entirely in graffiti, and in big red letters: FUCK BUSH.

And in the distance stands the Fernsehturm, the TV Tower that hovers

over Alexanderplatz like a giant steel dandelion.

The other side of my room overlooks a courtyard. Strands of flowering

vines crawl up walls, defying the October chill. A small koi pond

is lit from below. A few tables and chairs are scattered in the yard, but

it’s hard to imagine they’ve gotten much use. It’s been cold and rainy

since I arrived in Berlin rather suddenly, less than two days ago.

I go down to the breakfast room. A wall of windows faces the courtyard.

German tourists and businessmen sit at square tables eating cake,

salami, and muesli. Outside it’s gray and drizzly and the wind is gusty,

but they all seem used to it. Most of them, like me, have blue eyes.

The hotel is staffed almost entirely by young women dressed in

black. They are all very beautiful. “Guten Morgen,” one says as she leads

me to a table. Her name tag reads Astrid. “Kaffee?” she asks, tilting

her head to the side. I nod. As Astrid pours the coffee, her blond hair

drifts down her shoulder and she sighs, “Soooo . . .” Everyone says this

to me. I eventually discover that it means here you go, but not quite.

Nothing is what it seems here. Nothing translates. The word bitte

means please and you’re welcome and may I help you? When I walk

around the city, streets don’t have names like 14th Street or Avenue

A. My hotel is between Grosse Präsidentenstrasse and Oranienburger

Strasse. That’s two streets and sixteen syllables.

I’ve come to Berlin to see an exhibit at Klaus Beckmann’s Zukunftsgalerie,

curated by the owner himself. The latest show at the “gallery

of the future” is all about the past. Its theme is Ostalgie, the nostalgia

for the products, objects, and way of life that disappeared from the

East almost overnight, after the Wall fell, less than fifteen years ago.

I’m an art advisor in New York. I specialize in contemporary art

and tell people what to buy. Sometimes I consult for corporations,

but mostly I deal with private collectors, which means that these days,

I spend a lot of time with the newly wealthy—hedgefunders,

trophy wives, Europeans, that sort of thing. I often find myself trapped in

their cavernous apartments or strolling arm in arm with them through

galleries in Chelsea, dining out with their families, making small talk,

just hoping to close a sale.

Walking around Mitte, the neighborhood that bridges east and west,

I see graffiti everywhere. But it’s not fuck-you graffiti. It’s beautiful,

the wild bursts of color and ridiculous taglines. Art is everywhere—painted

on buildings, stenciled on doorways, plastered on pipes. It is

raw and, like much of Berlin, reminds me of New York in the seventies

and early eighties, the city of my youth.

I picture Times Square: the crowds, the lights, television screens

and scrolling headlines, the stock quotes, kidnappings, and natural

disasters. Endless information pouring across pixilated walls. It’s the

core of my city now, an advertisement for everything and nothing, the

void filled with a million things.

There’s nothing about Berlin that’s on similar display. It’s a cagey

peacock with its dazzling tail spread, walking away from you while

looking backward. It seems an insular and introspective culture, happy

to be on its own, connected by the dark threads of its knotty history.

Daniel would say that I’ve got it all wrong. A city unfolds, takes its

time. “Sleep,” he’d tell me. Because first impressions are never right.

Recenzii

"[An] affecting debut. . . . Schnall succeeds at bringing the city's strange beauty to life. This will strike a chord with anyone who’s been touched by the magic of Berlin."—Publishers Weekly

"A funny and moving debut."—Charles Arrowsmith, The Washington Post

“This is a pendulum of a book, swinging between rolling in smoky Kreuzberg techno clubs and strolling the preppy lushness of New York’s Upper West Side, and never being quite sure when or where we’re going to slip off and land. A love letter to Berlin, to travel, and to saying yes to life.”—Alan Cumming

“Eric Schnall’s gorgeous debut is everything you want in a novel—perceptive and witty, melancholy and honest, kind and full of heart. Better yet, his story is populated with the most hilarious and singular characters you could hope to meet on the page.”—Jenny Jackson, New York Times best-selling author of Pineapple Street

“An amazing feat. Wonderful books are like foreign travel itself. You’re dropped someplace unfamiliar, lost in a new language. You begin to feel your way around, and in the hands of a skilled writer like Eric Schnall you slowly but surely fall in love with place, with character, with words, ultimately gaining a new sense of self. I finished I Make Envy on Your Disco completely enchanted, and I can’t wait to book a return trip to Schnall’s work.”—Steven Rowley, New York Times best-selling author of The Celebrants

“One of the most delightful, smart, surprising, and unexpectedly affirming books I’ve ever read. Not unlike protagonist Sam Singer—who has fled his life in New York for an exquisitely rendered Berlin—I fell in love with every character who crosses his path.”—Steve Adams, Pushcart Prize–winning author of Remember This

“What if a city and the people you meet there get so under your skin that you see once more that life is full of beauty and possibility? I Make Envy on Your Disco will remind you that growing older is not just about what you leave behind but also about new beginnings, new relationships, and new ways of living in the world.”—Anton Hur, National Book Award finalist and author of Toward Eternity

“The characters in this hilarious, wistful, and moving novel will live with you long after you’ve read the last, aching page. I Make Envy on Your Disco is pure pleasure—a celebration of the intense, even transcendent connections we can make when traveling far from home.”—Carolyn Turgeon, author of Godmother and Mermaid

“In Eric Schnall’s fast-paced and funny debut novel, a successful New York art advisor finds himself perpetually discombobulated on a short business trip to Berlin. Moment by moment, we tag along as he continually loses—and eventually recovers—himself in a city that comes as vividly to life as the eclectic cast of characters he meets along the way. I loved this sharply observed and deeply touching book.”—Bill Hayes, author of Insomniac City

Descriere

I Make Envy on Your Disco is the story of a thirty-seven-year-old art advisor who, fed up with his life in New York, flies to Berlin for a gallery opening and finds a once-divided city brimming with excitement and possibility, yet facing an identity crisis of its own.