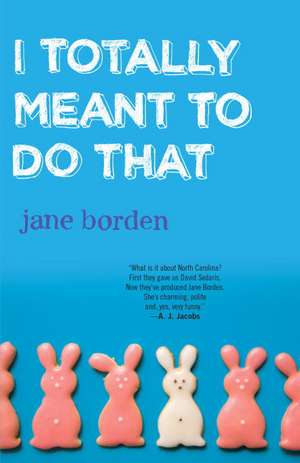

I Totally Meant to Do That: The Ultimate Guide to Surviving Your Teens And/Or Being Successful!

Autor Jane Bordenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2011

Anyone who has moved away from home or lived in (or dreamed of living in) New York will appreciate the hilarity of Jane's musings on the intersections of and altercations between Southern hospitality and Gotham cool.

Preț: 100.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.20€ • 19.84$ • 15.98£

19.20€ • 19.84$ • 15.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307464637

ISBN-10: 0307464636

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307464636

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

JANE BORDEN has contributed to Saturday Night Live, the New York Times Magazine, Comedy Central, VH1, Time Out New York, Modern Bride, and the New York Daily News. This is her first book; to find out where she lives, you'll have to read it.

Extras

Prologue: Waiting for the Raid Team

Shu-ku-ku-ku-CLANG! The last sliver of daylight disappeared as the metal gate shut me inside. I was trapped in one of those squalid knockoff handbag stores in Chinatown, alone, in the dark, and convinced I’d soon have this conversation: “So tell me, Jane, how were you sold into the sex- slave industry?” “Well, Svetlana, I tried to buy a fake Prada purse from a Canal Street stall with a Pokémon sheet for a door.”

That sheet was now on the other side of a very solid shutter. It click- locked to the ground and my knees went weak. Great: When they found my body, I’d have tee- teed all over my matching denim outfit. The store, if you can call it that, was no bigger than my minivan and it stunk of fishy noodle soup. I’d probably have to eat the vendor’s leftovers to stay alive. I knocked on the barrier and cried, “Hello? What’s happ’nin’?” No one answered.

I had come to town to see a Broadway show, eat at Tavern on the Green, and bring back a dozen knockoffs for my girlfriends in Raleigh. I had not come to pursue a career in a Chinese Mafia sweatshop. There was shouting outside. It had to be the cops. “Let me out of here!” I screamed. “I promise I wuh- int gonna buy nuthin!”

Lord Jesus, I didn’t want to go to jail. What would my book club think? What would I tell my husband, the contractor who was currently dove- hunting with the boys at Currituck? Or my twin sister, the one who had the cash for the bags, but couldn’t be there today because she’d taken the kids to the Hershey’s store in Times Square? Or my bible study leader, who’s a closeted homosexual, but . . . Wait, why am I lying to you? You’re not a counterfeiter. Sorry; old habits die hard.

Here’s the truth: I was trapped. And I was definitely wearing matching denim, but it was a disguise. I do not own a minivan or a wedding ring. I’ve never eaten at Tavern on the Green. And I wasn’t afraid; I’d been locked inside filthy Canal Street stalls before. It was part of my job description as a spy. My employer was Holmes Hi- Tech, a private- investigation firm that’s now defunct (otherwise I wouldn’t write this chapter; I may have been a spy, but I’m no rat). Our clients were Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Rolex, Polo, and other luxury- goods purveyors protecting their trademarks from the sale of illegal knockoffs. New York City’s Chinatown is one of the biggest counterfeiting centers in the world.

So even though Customs, the police, and the FBI are responsible for busting the illicit trade, a multibillion- dollar industry flourishes regardless, leaving a niche plenty big for our small, spunky Midtown office. When I first interviewed for the secret- shopper position, and mentioned it to my mother, she forbade me to accept the job. She actually used the word “forbid,” a tactic previously unemployed, I suppose, because it had never been necessary. The closest thing to crime rings in Greensboro were the hippie drum circles on the UNC- G campus. And anyway, my parents typically let me make my own mistakes. Although I wish she’d forbidden my eighth- grade perm, going undercover in Chinatown was where she drew the line. Years later, when I confessed to disobeying her, she shot me a look that could have curled hair without chemicals. Honestly, though, I never felt unsafe in Chinatown; I had anonymity. My boss was the one who received death threats. He was also the one shouting with the vendor outside the Pokémon stall, which I of course knew; I’d been expecting his arrival. Here’s how it went down.

A week prior, another of my fellow “spotters” had cased the same location, looking for fake versions of our clients’ products. While she fingered purses and scarves, tried on sunglasses, and generally pretended to shop, she was actually memorizing all of the brands being sold, the kinds of items within each brand, in which part of the store each was displayed or behind which secret remote- controlled doors each could be found— multiplied by however many other locations she’d been assigned to visit before she could leave that section of Canal Street and safely purge her brain via pen and paper in a restaurant bathroom. The elderly should pursue this line of work as an exercise to stave off Alzheimer’s. With this intelligence my boss had obtained a warrant to confiscate Pokémon’s contraband. He’d surprise the vendor by rolling in with a raid team of off- duty cops and fire fighters. But first, they needed confirmation that the goods remained on- site. Enter me.

By 11:00 a.m. on a Saturday, almost every square foot of Canal Street, including parts of the road, is occupied by merchandise. Items spill out of stores onto the sidewalk: card tables whose legs splay under the weight of backpacks and wallets, buckets that brim with baby turtles crawling to the top of a mound of themselves. Food carts sell dumplings and noodles curbside. Women wheel jerry- rigged carts stacked with pirated DVDs. Adolescent boys hawk water and soda from coolers on wheelbarrows. Be careful not to trip over one of the dozen or so varieties of motorized toy that flip, flop, slither, and writhe through the squares of municipal concrete just beyond the cash registers that could make them your own. Invisible hand of the market? If Adam Smith could wander modern Chinatown, he’d have seen it plain as day. And people call the Chinese communists.

I hit our target, near Baxter on Canal, in my tasteless denim ensemble, around 11:10 and immediately saw what I was after: counterfeit purses. They were on display, so I didn’t need to weasel my way through a back room, down a secret staircase, or into a crawl space in the ceiling. It’s the little perks that matter. At that point I acted as if I felt my phone vibrating. When I flipped it open, pretending to answer, I punched the last- number dialed button.

“Hello?” I said.

Ringing.

“Hey Carol! What’s happ’nin’?”

Ringing.

“Not much. I’m shopp— ”

“Jane?” answered my manager at Holmes Hi- Tech.

“— ing. Yep.”

“Are you at the location?”

“Yes. Dinner tonight; y’all should definitely come!”

“So the bags are there?”

“You got it!”

“Great, I’ll send the raid team now.”

“No, you’re beautiful!” (That last part was just for me.)

I put my phone back in a pocket and moved through the store slowly, regarding every item, taking time so as not to run out of merchandise to inspect. I couldn’t leave until the guys arrived; the knockoffs were the evidence my boss took to court, so without them we had no case, and therefore no profession. If Pokémon got spooked for some reason and pulled the illegal bags from the floor, I had to know where he put them, whether in one of the aforementioned hiding spots, or in another location on another block, an outcome I feared, as it would require me to follow, and I was uncomfortable tailing criminals through the streets of Chinatown. I am not a subtle person.

But this vendor wasn’t worried about getting busted by a spy. Neither was he concerned about lying to customers. While I modeled scarves, another woman in the stall pointed to a pocketbook without a label and asked, “Is this Gucci?” Without pausing, the merchant answered, “Yes.” To trained eyes such as mine or those of a Madison Avenue doyenne, the item in question was clearly patterned after Louis Vuitton. I assumed the vendor was mistaken, until another woman, a few minutes later, grabbed the same purse and asked, “Is this Chanel?” to which he also responded, “Yes.” Whatever it takes to make a sale; tell them what they want to hear. Where the hell was the raid team? It had been almost fifteen minutes. No one spends that much time in a store the size of a minivan unless considering a major purchase, in which case I probably would have approached the salesman by now. But I didn’t want to engage him for fear he’d later suspect my involvement, and then, suddenly, oh my God I was the only other person in the store, but, phew, he went outside, and . . .

Shu- ku- ku- ku- CLANG!

The pleather purses are manufactured for pennies, either in China or in sweatshops, and, obviously, not taxed. Markups can reach eight thousand percent. Salesmen, leases, aliases, and passports are all a dime a dozen; the crooks only cared about the bags— not for their actual worth, but rather their potential, imagined worth. In this never- ending battle, the contraband was our Jerusalem: All sides revolved around it, gained definition from it, and, therefore, assigned it a value far greater than its face.

That’s why I was locked inside. Vendors protected their holy crap. They were familiar with raids, so if they saw the team approach— it’s hard to miss six beefy mustachioed Irish dudes rolling out of a white van like a clown car of sports announcers— they’d immediately close shop, regardless of patrons inside. Occasionally I was trapped with other confused women, sometimes by myself, but never for long: Warrants trump locks. When the gates inevitably rose on the other side of the Pokémon sheet— which was, by the way, counterfeit itself— I scurried out like a frightened tourist, careful to avoid eye contact with the guys. I could congratulate them later over beers but couldn’t blow my cover at the moment because a couple of days later, I’d be back in Chinatown canvassing the same stretch of junk. My income hinged on my ability to be multiple people. Problem was: I’m not much of an actor.

In the spring of my senior year in high school, I took a season off sports to broaden my artistic horizons. I played Miss Bessom in our theater department’s production of Shirley Jackson’s adaptation of The Lottery. All you need to know about the play is that everyone wears gray and people die, but then again you’re probably familiar with the story after seeing your high school drama club production. I don’t know why this brutally dark play is so popular with adolescents . . . oh wait, yeah I do. Anyway, I was horrible. I had a handful of lines and delivered each like a kid who bowls by holding the ball between her legs, and then while squatting, thrusts it down the lane. I am also a bad

bowler. Our director said to smile and project. Apparently I understood that to mean grimace and shout. I’d have been hailed as a star had the stage directions for Miss Bessom read, “played as a man with hearing loss and hemorrhoids.” Actually, for my portrayal to have been believable, the description would have needed to read, “played as Jane with hearing loss and hemorrhoids,” for I was never actually in character. While the line “I declare, it’s been a month of Sundays since I’ve seen you!” came out of my mouth, running through my head was: “Who talks that way? Why not just say, ‘it’s been a month’? The Sundays are implied.”

The only point in each performance when I felt the slightest association with how Miss Bessom might think and feel was when the Mrs. Dunbar character said to Bessom/me, “They told me you were gettin’ real fleshy.” Bottom line: I couldn’t act my way out of a paper bag if it were made of me- sized holes. Whatever, no biggie— except that every other spotter at Holmes Hi- Tech was an actor. In fact, it was a thespian friend of mine who’d introduced me to the gig. Actors liked the work because, in addition to the flexible hours, it allowed them to practice their craft. I pursued the job because it sounded cool, the closest to clandestine this suburban girl could get. I wish I were able to reveal to you a deeper, more complicated motivation— a consuming desire to serve justice, a fascination with Chinese culture, a lurid role- playing fetish. “It sounded cool” is a lame provocation, but there it is nonetheless. I’ve grown accustomed to the disappointment engendered by that response. People prefer a good story.

My actor coworkers wrote new narratives every morning. After exchanging flyer postcards for various low- budget blackbox- theater one- acts, they’d transform themselves. I remember this brunette who earned the moniker “chameleon.” She left the office once as a Canadian- accented tourist and returned that afternoon a Goth teenager, replete with pale makeup and ripped skull- and- crossbones tights. I didn’t even recognize her.

She was one of only a few who switched from one identity to another beyond the office. Our manager discouraged the practice because there was nowhere safe to do it. She also warned us not to take notes anywhere, not even in a bank or pizza shop, and not to leave information on voice mails within earshot of anyone. She’d lost two spotters that way, one who’d blown his cover in front of an employee at Pearl Paint, and another who’d done so next to an elderly man playing mah- jongg in Columbus Park. Our manager said everyone in Chinatown was involved, “Everyone is in on it.” Obviously, that’s egregious hyperbole, but I think what she meant to say was that there was no establishment at which we could be certain no one was involved. Indeed, I once happened across a multi- thousand- dollar phony- Rolex deal while hitting the loo at the Lafayette Street Holiday Inn.

The most convincing performers scored the respected roles. One time, during assignments, our manager told this guy Henry that she’d be helping with his disguise that morning. Authenticity was critical, as they needed him to case a location for four straight hours, to monitor who came and went. So Henry became a junkie. He passed the afternoon sitting or standing on the curb, intermittently nodding off. Back at the office, while demonstrating the smackhead lean, wherein the body reaches an angle nearly 45 degrees but somehow, Newton defyingly, does not fall, he explained that he’d delivered a depiction so convincing, it’d attracted the attention of both a cop, who told him he was disorderly and threatened to arrest him, and a born- again Christian, who told him about Jesus and threatened to save his soul.

And then there was I, approaching the disguise closet each time with only this question: Which wig today, the brown one that resembles my actual hair? Or the brown one that’s exactly like my actual hair? After the great Miss Bessom debacle, I knew better than to try to act like someone else. Also, I’m a terrible vocal mimic. I can’t even ape midwestern, and that’s the O- negative blood type of accents: It can flow through anyone. It’s the Bill Cosby impression of accents. And I am also bad at those . . . unless what’s been requested is “Bill Cosby doing a Japanese man.”

So only two characters lived on my résumé. One was me, and the other was a heightened version of me, the me I imagined I’d be if I’d stayed in North Carolina. Alterna- Me had, for starters, a much thicker drawl, which I could pull off because rather than “doing an accent,” I merely tapped into the way I sound when I’ve had too much to drink. She was young, married, and applying to law schools near her home in Raleigh. She wore pearls and belonged to things like supper clubs and congregations. She grocery shopped at the Harris Teeter and ate lunch on Sundays at the Carolina Country Club. If ever questioned, I could have recited her biography easily. I knew everything about her, even though I am not the one who created her.

“Don’t you want to come home and go to law school?” my uncle Lucius used to ask nearly every time we spoke. “Raleigh’s nice, you know. It’s ranked on the list of most livable cities.”

“I’ll throw a luncheon for you!” Aunt Jane, for whom I am named, would add, having picked up another phone in the house. “And get you into all the clubs.”

“You can join the Episcopal Church.”

And then my aunt would shout, “I’ll give you all my jewelry!”

So, yeah, this girl was a big part of my life. And somehow, she worked. I canvassed Canal Street three, occasionally four times a week, always wearing a shade of the same person, and got away with it. I didn’t need to be a chameleon because the counterfeiters bought me. Eventually, I developed a theory regarding why. Since they knew how we operated, merchants were suspicious of every potential customer, scrutinized each for tells that he or she might be a spy. I noticed them paying special attention to certain people while ignoring others, whomever they could quickly disregard as guileless. I never needed to become a different person, as long as the original was consistently overlooked. And as I’ve come to understand, people— from, apparently, either hemisphere— assume Southerners are innocent.

It was a wondrous thing to witness. Salesmen eyed me warily until the moment I purred, “Y’all got Gucci?” when they’d instantly drop their guards and either lift a sheet, pull a trash bag from a desk, or open a concealed door in a false wall. It’s not as if we were suddenly pals; there were no smiles or secret handshakes. What happened was a dismissal. They dismissed me, shifted mentally from looking at me to looking beyond me, over my shoulder for the next potential threat.

Astute readers would argue that any accent could have put them at ease. And for the most part that’s true. Counterfeiters trust tourists. But I’m telling you, there’s something foolproof about the drawl. Unlike some of the other spotters, I was almost never denied access. I can only posit that Barney Fife and Elly Mae Clampett exist in the collective unconscious, because I don’t think Mao fed his starving republic on a diet of TV Land classics. Which is to say that maybe it was more than the accent; maybe it was also my accompanying wide eyes and gullible smile. Come to think of it, maybe it was I who worked like a Southern charm.

Once, I asked a peddler if he had “LV” in the store and he whispered, “Not now.”

“Why?” I responded vapidly. He nodded toward another woman. “Come back later when she’s gone. She pretends to shop, but she’s a spy.”

Whoever she was, she didn’t work for us. Possibly she reported to Customs, but I doubt it. Either way, a moment later he threw her out of the store so that I, the spy, could shop. Not only did he fail to suspect me, he shared delicate information! My countenance and personality telegraphed a prodigious naïveté. It’s a circumstance discouraging and frustrating, and I didn’t mind at all using it against them. Still, even with my airtight Hee Haw avatar, I couldn’t get cocky. A couple of times during my stint with the firm, coworkers returned from a day on the streets and heard, when the elevator opened, “You’ve been burned.” Our manager knew immediately because she had informants on the inside. That was a spotter’s worst day of work and also his or her last. It’s kind of like accidentally firing yourself.

Typically, though, the response was, “I figured.” An agent knows when the jig is up. If you approach a shop and it closes its gates, you’ve been burned. If you turn around and a shopkeeper you’ve been watching is following to see where you’re going, you’ve been burned. If passing one of the sentinel lookouts, who stand on stools at major intersections in Chinatown during the highly trafficked weekends, leads him to reach for his mobile phone and set off a chain reaction of cellular warnings that runs down Canal Street like those mountaintop bonfires in The Return of the King, you’ve been burned.

Game over.

In other words, I couldn’t work every day. But it was summer, and in your twenties, that means weddings, which require plane tickets, gifts, and for me, that summer, two bridesmaids dresses. I was behooved by teal-green ruffles to seek supplementary employment. I picked up temp work here and there. And because I had experience waiting tables in college at a wing joint called Pantana Bob’s— for which I wore a T- shirt that read “Bob’s Got a Big Deck!”— I scored one shift a week at the legendary West Village brewpub Chumley’s.

It was cush. The owner promised a set amount each shift, so if my tips were short, he’d pay out the difference from his pocket; decent guy. He rarely had to, though. The place stayed packed. Both locals and tourists competed to sit in a booth that might have been occupied by John Steinbeck, Jack Kerouac, Simone de Beauvoir, F. Scott Fitzgerald, J. D. Salinger, Willa Cather, e.e. cummings, William Burroughs, Norman Mailer, Ernest Hemingway, Edna St. Vincent Millay, or any other of the dozens of literary luminaries who are said to have haunted the windowless speakeasy either during or after its Prohibition heyday. It didn’t matter that flies swarmed the back room, the jukebox featured only opera, or that sawdust inevitably found its way into your overpriced shepherd’s pie and frequently flat beer. With a pedigree such as that, derelictions are deemed charming. I agreed. I loved the joint.

I discovered the venerable institution through Lou, the elder of my two older sisters, who lived in the West Village when I arrived in New York. She and her friends, many of whom went to college with her, took me under their collective wing as the kid sister they knew me to be— emphasis on kid. Lou and I are seven years apart, so those college pals hadn’t seen me since the perm. Actually, Lou and I hadn’t seen much of each other either. She left for boarding school when I was eight. Of course, we visited over holidays and family vacations, but we didn’t have a relationship outside of the family unit. It was different with my middle sister, Tucker, but with Lou . . . I spent more of my cognitive childhood imagining her than experiencing her.

I remember trying to picture her New York apartment. In my mind, it had a tree- lined street and simple concrete stoop. I’d visualize ascending a dark and steep stairwell; I could see myself opening the door. I knew the layout of the fictional furniture and the color of the imaginary couch.

Of course, her real apartment was completely different, and hilariously smaller— particularly when, in addition to her and her roommate, I was there, which was all of the time. I’d come over to watch TV, or have a glass of wine, or just because I could. The first time we ordered takeout, I painstakingly separated out the duplicate menus in order to beef up my collection uptown, before Lou explained that New York restaurants don’t deliver beyond their immediate area: “Did you think they’d get on the subway with your pad thai?”

She teased me a lot, but mostly she mothered me, which I guess I needed at the time because why else would I think it was OK to sleep over in her tiny double bed, like, once or twice a week? I would have hated me. She gave me a key, and occasionally I’d let myself in at three in the morning, when they were both asleep, have a snack, open Lou’s door, and ask her to “scoot over.” But most of the times that I stayed were on nights when we’d been out together carousing in her neighborhood joints. Everywhere in the West Village was legendary. We went to Corner Bistro for the best burgers in the city, and to the White Horse Tavern, where Dylan Thomas drank himself to death. Lou and I stood in line for cupcakes at Magnolia Bakery and caught a scene of Sex and the City being shot on her block.

When my lease was up in August, I decided to move to the corner of Perry and Hudson streets. My friends thought I was crazy; the apartment on Eighty- Seventh was a block from Central Park, had a private garden with a tree and a hammock, and my portion was $300 less a month than I’d be paying on Perry. Why was I moving to the West Village?

“I don’t know,” I said and shrugged my shoulders. “Sounds cool.”

Unfortunately, Lou wasn’t there anymore. She’d moved back to North Carolina the month prior. She lived in New York for seven years, but we overlapped for only one. Oh well, at least she’d had a chance to show me the ropes, for example, how to get into

Chumley’s.

The main entrance was hidden in the back of a courtyard on Barrow Street, and the back door was unmarked at 86 Bedford; during Prohibition, when a bribed cop called to warn the barkeep of an ensuing raid through the courtyard, the crowd was instructed to exit on Bedford, or to “ eighty- six it,” which is the origin of that famous idiom. Patrons could also escape through a secret bookcase that led to an alley. Apparently, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre consummated their marriage in one of the booths. And it’s where James Joyce wrote Ulysses.

Oh geez, oops: I’m lying again. Sorry: you’re not diners. I guess, while working there, it became second nature. Those stories, and a dozen others phonier than a character in The Catcher in the Rye, were tossed to patrons thirsty for more than a pint. I heard some of them from other servers, a few from the walking- tour and bar- crawl guides who led their keeps inside, and most from curious patrons who’d picked up the apocryphal trivia elsewhere: travel books, blogs, drunkards at other neighborhood haunts. Everyone was in on it.

Here’s the truth. There is an entrance at 86 Bedford, but the phrase “eighty-six it” had been in use— and in print— long before Chumley’s opened. There was also a secret bookcase, but it went to the kitchen. And it’s pretty well documented that James Joyce wrote Ulysses in Zurich and Paris. As for the young Fitzgeralds . . . I can’t prove they didn’t . . . and they were married in New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral . . . but still, sometimes you have to trust your gut, and mine thinks even Gatsby and Daisy wouldn’t have boinked in a pub. As one of the walking- tour guides put it, “Writers are known to get drunk and embellish.”

No one set out to spread distortions. It started innocently. In fact, I believed the tales myself until a fellow employee laughed at one of my questions and asked, “You do know that half of those stories are false?” But then, it became hard to stop— particularly when customers asked leading questions. One wanted to know if the ladies’ room had once been a dumbwaiter that carried people to a gambling den on the second floor. Another had heard that, actually, the dumbwaiter went to the basement and was how they carried the booze inside. Or, according to someone else, that’s what the trapdoor was for, since it connected to a tunnel that led to the rum- delivering boats. Still others pointed to that door in the floor and told their friends, “Runaway slaves used to climb through that hole because when this was a blacksmith’s shop, it was a stop on the Underground Railroad.”

And then they’d look up at me, all of them, with eager eyes, and ask, “Isn’t that right?”

Um, er, thwlllpb, “Sure is! Neat, huh?” Tell them what they want to hear. The only time I didn’t play along, I instantly regretted it. While I distributed menus, a father told his children that this had been where Dylan Thomas died.

“Actually,” I piped in, “you’re thinking of the White Horse.” His face sank, and so did his children’s. What had I achieved? What mattered more: verifying a useless fact or giving them a memorable meal— one whose imagined worth exceeded the menu’s prices? Besides, I can’t say for sure that Thomas didn’t stop by Chumley’s for one round before heading to the White Horse, just as it’s impossible to prove that the blacksmith shop wasn’t part of the Underground Railroad, or that the bookcase hadn’t, at one point, led to the street. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “Sometimes I don’t know whether Zelda and I are real or whether we are characters in one of my novels.”

And anyway, Dylan Thomas died in St. Vincent’s Hospital. So from that point forward, I just said yes to all of the legends. “I heard Fitzgerald wrote Gatsby here.” He sure did, and in fact, you are sitting in the same booth. “Is it true that R.F.K. sketched out his

presidential campaign platform in this bar?” Yeah, and would you believe it was in this exact booth! You could have asked me anything. Did William Burroughs name Naked Lunch after Chumley’s BLT? Is that the barstool where e.e. cummings gave up capital letters? Is this where a blind John Milton dictated Paradise Lost to his amanuensis? You bet, and I don’t want to blow your mind, but it was in this very booth.

Wait a second, the fictional you is thinking, Milton died before the West Village existed. Sure, but didn’t you know that the dumbwaiter in Chumley’s was once a time machine? After escaping entrapment in the Pokémon- sheet cave, I cut down a block and moved swiftly on Walker Street toward the center of Chinatown, intuiting that my next assignment would be on the west end of Canal, where no one had seen me yet, and knowing that I’d need to reach it before the news of the last raid did.

I called the office for the target and sure enough, it was still several blocks away. When I arrived, the goods on display were all anonymous, legal. I feared it was too late, but I milled about regardless. A middle- aged woman standing nearby solicited advice about a wallet she considered.

“I can’t believe it’s real leather for this cheap,” she giggled in a thick Long Island accent.

“It’s not real,” I told her, maintaining my harmless Southern drawl, but unable to disguise the skepticism.

“But it says so on the wallet,” she said incredulously.

“That doesn’t mean anything.” I don’t know why I chose this battle. I guess, sometimes I was bothered less by the counterfeiters—even though they annually steal around one billion tax dollars from New York City, support a system of illegal-immigrant indentured servitude, and occasionally fund terrorism— than I was by the willful naïveté of the bargain hunters. How could she believe that piece of junk was real? Were we looking at the same wallet? It had a plastic sheen. The stitching wasn’t even in straight lines. At this point, she shouted across the store to the vendor, intent on settling the dispute: “Is it real?”

“Of course,” he said, “it says so on the label.”

She looked up at me and actually said, “I told you so.”

Whatever, I thought. You are not my child. Then I saw a man walk out of the back room with a thirty-gallon trash bag slung over his shoulder, and instantly stopped caring about the fool from Long Island. It wasn’t too late after all. They’d merely removed the contraband from the front room; only now were they excising it from the premises. I felt my heartbeat accelerate as I casually spun my back to him, a move that also allowed me to see which way he turned outside the door— I would have to follow. Then I flipped through the “real” wallets one more time, giving him a several- second head start, and pursued the tail.

Following people was the only time I didn’t feel completely confident and comfortable on the job. When gathering intelligence, I could come and go as I pleased, depending on who was or wasn’t looking. But while tailing a mark, I couldn’t cut my own path. And I feared that would draw suspicion, betray me; no two people follow the exact same path. I maintained a generous distance between us as we headed east, and I called the office to alert the raid team of a change in plans. On the other side of Broadway, he crossed south on Canal and then did what I’d feared he would seconds earlier: took a right on Cortland Alley. No one walks through Cortland Alley. It’s a narrow passage that spans two blocks and has no storefronts. You might recognize it from appearing in movies whose scripts call for an alley that no one walks through. It is not the sort of grimy, dark, vermin- infested, less- traveled road down which a prim, tomato- pie- making, y’ allspewing gal from the sticks would, on a whim, mosey.

True to its nature, this morning Cortland Alley was empty. I lingered on the corner of Canal before turning, aiming to diminish the amount of time we’d be alone on the block, but I had to enter: The distance to the next intersection is long enough that if I waited until he arrived at it, and he turned, he’d have had an opportunity to turn again before I arrived, and I would’ve lost him for good. So I joined.

He never looked back. I reminded myself that criminals are dumb. After a few more blocks, he led me not to another handbag store, which was typically the case as ringleaders control several locations, nor to a warehouse- like storage facility, which is how we made the occasional major bust, but to a small innocuous food market on a side street. Everyone is in on it.

He nodded to a guy, who nodded back and then led him through a door behind the counter. I grabbed a produce baggie. The room was redolent of fish alive, dead, dried, and dying. Every piece of text contained within was written or printed in Chinese. I was the only Caucasian inside and desperately tried to appear as if I had a reason to be, as if I’d come for something specific. That ended up being three stocky white root vegetables, the least unfamiliar items for sale. Burdock? Parsnip? I have no idea what I fried and ate that night.

Confident that the contraband would not move again, I left the market and called in its address to my manager. When I met the team that night at the Irish pub, I heard they’d rolled into the grocery with a warrant an hour after I left. The bags were exactly where I’d said they’d be. Somebody bought me a beer.

The next day I worked at Chumley’s, slinging burgers and returning beers when they became flies’ watery graves. But the day after that I was back in Chinatown. I should’ve waited longer, let things cool. I cased a few stalls: usual shtick, usual scores. And then, near the intersection of Canal and Centre, a man in a baseball cap caught my eye and held it for a millisecond longer than I expected him to.

I felt it immediately. I continued in the same direction at a casual pace for a block and a half, and then looked over my shoulder. Sure enough, he was behind me— talking on his cell phone. To confirm what I already knew, I popped into another storefront or two, but, wouldn’t you know: No one was selling knockoffs anymore that day, not even when I batted my eyelashes, drew out my “i”s, and talked about Jesus.

Returning to the office, I expected a burn notice, but when the elevator doors opened all I heard was, “Hey Jane.” It’s possible I was wrong but . . . there’s no way I was wrong. An agent knows. I must’ve blown my cover in the grocery; Baseball Cap must have been in that market.

On Canal Street, I drew no suspicion, because I looked like a tourist, sure, but also because the salesmen had an incentive to believe I was who I said I was: They wanted to sell bags. Just like the fool from Long Island believed the wallets were real because she wanted to have found a deal on a luxury item. It was the incentive that had made me a good spy— not my own work— and no one in the grocery store had it. They saw my syrupy Southern- tourist persona for what it was: a knockoff unraveling at its haphazardly stitched seams.

I was too ashamed to tell my boss, so instead I removed my name from the remainder of the schedule and left. Not long after that, upon entering my apartment building on the corner of Hudson and Perry, I walked upstairs and stuck my key in the lock, but it wouldn’t turn. Duh, I thought, as I instantly realized my gaffe: wrong floor. I deduced the error quickly because I was familiar with the mistake; I made it about once a week that year. It was a strange and annoying affliction that has never struck me in any other of my many dwellings.

My place was on the third floor, first door at the top of the stairs. Sometimes I stuck my key in the right lock. Other times I tried to open the corresponding door on the second floor, and sometimes even the one on the fourth. My neighbors never said anything; I was mostly a nuisance to myself.

In this particular instance, however, after recently being burned, the pattern played out a little differently. When I yelled at myself in my head— Geez, it’s like you’re a tourist in your own home!— I saw that I was. The West Village wasn’t home. I realized that I didn’t even like it that much. In fact, I generally hung out in the bars and restaurants of other neighborhoods. I’d hardly decorated my room.

The apartment felt counterfeit. So I started thinking backward. If this seemed obvious now, but I hadn’t noticed any of it before, then my ignorance must have been willful, which means I’d had an incentive— one whose imagined worth was so great, I’d gone more than $4,000 in debt paying rent in a neighborhood I couldn’t afford.

OK, here is where I tell you that I lied one last time. The truth is this: I do know why I moved to the West Village. I was chasing Lou. Finally, finally I’d reached her, and suddenly she was gone again. But in the legendary West Village, I could retrace her steps. Whenever I fancied, I could pop into Magnolia for a chocolate cupcake or go dancing at Automatic Slims. I could eat burgers at Corner Bistro and tell myself with eager eyes, “I bet Lou sat here once . . .in this very booth!”

I had spent so many years imagining her before, it was easy to slip back into the habit. But I wasn’t chasing her; I was chasing her narrative, trying to consume her authentic experience— an inherently inauthentic pursuit. No two people follow the exact same path. And I couldn’t even be certain the narrative was true. I’d cobbled the account together from anecdotes apocryphal and embellished by drink. I had the right key but it was in the wrong lock. If the world is made of narratives, then it was time I write my own.

And I may as well start from the beginning.

Shu-ku-ku-ku-CLANG! The last sliver of daylight disappeared as the metal gate shut me inside. I was trapped in one of those squalid knockoff handbag stores in Chinatown, alone, in the dark, and convinced I’d soon have this conversation: “So tell me, Jane, how were you sold into the sex- slave industry?” “Well, Svetlana, I tried to buy a fake Prada purse from a Canal Street stall with a Pokémon sheet for a door.”

That sheet was now on the other side of a very solid shutter. It click- locked to the ground and my knees went weak. Great: When they found my body, I’d have tee- teed all over my matching denim outfit. The store, if you can call it that, was no bigger than my minivan and it stunk of fishy noodle soup. I’d probably have to eat the vendor’s leftovers to stay alive. I knocked on the barrier and cried, “Hello? What’s happ’nin’?” No one answered.

I had come to town to see a Broadway show, eat at Tavern on the Green, and bring back a dozen knockoffs for my girlfriends in Raleigh. I had not come to pursue a career in a Chinese Mafia sweatshop. There was shouting outside. It had to be the cops. “Let me out of here!” I screamed. “I promise I wuh- int gonna buy nuthin!”

Lord Jesus, I didn’t want to go to jail. What would my book club think? What would I tell my husband, the contractor who was currently dove- hunting with the boys at Currituck? Or my twin sister, the one who had the cash for the bags, but couldn’t be there today because she’d taken the kids to the Hershey’s store in Times Square? Or my bible study leader, who’s a closeted homosexual, but . . . Wait, why am I lying to you? You’re not a counterfeiter. Sorry; old habits die hard.

Here’s the truth: I was trapped. And I was definitely wearing matching denim, but it was a disguise. I do not own a minivan or a wedding ring. I’ve never eaten at Tavern on the Green. And I wasn’t afraid; I’d been locked inside filthy Canal Street stalls before. It was part of my job description as a spy. My employer was Holmes Hi- Tech, a private- investigation firm that’s now defunct (otherwise I wouldn’t write this chapter; I may have been a spy, but I’m no rat). Our clients were Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Rolex, Polo, and other luxury- goods purveyors protecting their trademarks from the sale of illegal knockoffs. New York City’s Chinatown is one of the biggest counterfeiting centers in the world.

So even though Customs, the police, and the FBI are responsible for busting the illicit trade, a multibillion- dollar industry flourishes regardless, leaving a niche plenty big for our small, spunky Midtown office. When I first interviewed for the secret- shopper position, and mentioned it to my mother, she forbade me to accept the job. She actually used the word “forbid,” a tactic previously unemployed, I suppose, because it had never been necessary. The closest thing to crime rings in Greensboro were the hippie drum circles on the UNC- G campus. And anyway, my parents typically let me make my own mistakes. Although I wish she’d forbidden my eighth- grade perm, going undercover in Chinatown was where she drew the line. Years later, when I confessed to disobeying her, she shot me a look that could have curled hair without chemicals. Honestly, though, I never felt unsafe in Chinatown; I had anonymity. My boss was the one who received death threats. He was also the one shouting with the vendor outside the Pokémon stall, which I of course knew; I’d been expecting his arrival. Here’s how it went down.

A week prior, another of my fellow “spotters” had cased the same location, looking for fake versions of our clients’ products. While she fingered purses and scarves, tried on sunglasses, and generally pretended to shop, she was actually memorizing all of the brands being sold, the kinds of items within each brand, in which part of the store each was displayed or behind which secret remote- controlled doors each could be found— multiplied by however many other locations she’d been assigned to visit before she could leave that section of Canal Street and safely purge her brain via pen and paper in a restaurant bathroom. The elderly should pursue this line of work as an exercise to stave off Alzheimer’s. With this intelligence my boss had obtained a warrant to confiscate Pokémon’s contraband. He’d surprise the vendor by rolling in with a raid team of off- duty cops and fire fighters. But first, they needed confirmation that the goods remained on- site. Enter me.

By 11:00 a.m. on a Saturday, almost every square foot of Canal Street, including parts of the road, is occupied by merchandise. Items spill out of stores onto the sidewalk: card tables whose legs splay under the weight of backpacks and wallets, buckets that brim with baby turtles crawling to the top of a mound of themselves. Food carts sell dumplings and noodles curbside. Women wheel jerry- rigged carts stacked with pirated DVDs. Adolescent boys hawk water and soda from coolers on wheelbarrows. Be careful not to trip over one of the dozen or so varieties of motorized toy that flip, flop, slither, and writhe through the squares of municipal concrete just beyond the cash registers that could make them your own. Invisible hand of the market? If Adam Smith could wander modern Chinatown, he’d have seen it plain as day. And people call the Chinese communists.

I hit our target, near Baxter on Canal, in my tasteless denim ensemble, around 11:10 and immediately saw what I was after: counterfeit purses. They were on display, so I didn’t need to weasel my way through a back room, down a secret staircase, or into a crawl space in the ceiling. It’s the little perks that matter. At that point I acted as if I felt my phone vibrating. When I flipped it open, pretending to answer, I punched the last- number dialed button.

“Hello?” I said.

Ringing.

“Hey Carol! What’s happ’nin’?”

Ringing.

“Not much. I’m shopp— ”

“Jane?” answered my manager at Holmes Hi- Tech.

“— ing. Yep.”

“Are you at the location?”

“Yes. Dinner tonight; y’all should definitely come!”

“So the bags are there?”

“You got it!”

“Great, I’ll send the raid team now.”

“No, you’re beautiful!” (That last part was just for me.)

I put my phone back in a pocket and moved through the store slowly, regarding every item, taking time so as not to run out of merchandise to inspect. I couldn’t leave until the guys arrived; the knockoffs were the evidence my boss took to court, so without them we had no case, and therefore no profession. If Pokémon got spooked for some reason and pulled the illegal bags from the floor, I had to know where he put them, whether in one of the aforementioned hiding spots, or in another location on another block, an outcome I feared, as it would require me to follow, and I was uncomfortable tailing criminals through the streets of Chinatown. I am not a subtle person.

But this vendor wasn’t worried about getting busted by a spy. Neither was he concerned about lying to customers. While I modeled scarves, another woman in the stall pointed to a pocketbook without a label and asked, “Is this Gucci?” Without pausing, the merchant answered, “Yes.” To trained eyes such as mine or those of a Madison Avenue doyenne, the item in question was clearly patterned after Louis Vuitton. I assumed the vendor was mistaken, until another woman, a few minutes later, grabbed the same purse and asked, “Is this Chanel?” to which he also responded, “Yes.” Whatever it takes to make a sale; tell them what they want to hear. Where the hell was the raid team? It had been almost fifteen minutes. No one spends that much time in a store the size of a minivan unless considering a major purchase, in which case I probably would have approached the salesman by now. But I didn’t want to engage him for fear he’d later suspect my involvement, and then, suddenly, oh my God I was the only other person in the store, but, phew, he went outside, and . . .

Shu- ku- ku- ku- CLANG!

The pleather purses are manufactured for pennies, either in China or in sweatshops, and, obviously, not taxed. Markups can reach eight thousand percent. Salesmen, leases, aliases, and passports are all a dime a dozen; the crooks only cared about the bags— not for their actual worth, but rather their potential, imagined worth. In this never- ending battle, the contraband was our Jerusalem: All sides revolved around it, gained definition from it, and, therefore, assigned it a value far greater than its face.

That’s why I was locked inside. Vendors protected their holy crap. They were familiar with raids, so if they saw the team approach— it’s hard to miss six beefy mustachioed Irish dudes rolling out of a white van like a clown car of sports announcers— they’d immediately close shop, regardless of patrons inside. Occasionally I was trapped with other confused women, sometimes by myself, but never for long: Warrants trump locks. When the gates inevitably rose on the other side of the Pokémon sheet— which was, by the way, counterfeit itself— I scurried out like a frightened tourist, careful to avoid eye contact with the guys. I could congratulate them later over beers but couldn’t blow my cover at the moment because a couple of days later, I’d be back in Chinatown canvassing the same stretch of junk. My income hinged on my ability to be multiple people. Problem was: I’m not much of an actor.

In the spring of my senior year in high school, I took a season off sports to broaden my artistic horizons. I played Miss Bessom in our theater department’s production of Shirley Jackson’s adaptation of The Lottery. All you need to know about the play is that everyone wears gray and people die, but then again you’re probably familiar with the story after seeing your high school drama club production. I don’t know why this brutally dark play is so popular with adolescents . . . oh wait, yeah I do. Anyway, I was horrible. I had a handful of lines and delivered each like a kid who bowls by holding the ball between her legs, and then while squatting, thrusts it down the lane. I am also a bad

bowler. Our director said to smile and project. Apparently I understood that to mean grimace and shout. I’d have been hailed as a star had the stage directions for Miss Bessom read, “played as a man with hearing loss and hemorrhoids.” Actually, for my portrayal to have been believable, the description would have needed to read, “played as Jane with hearing loss and hemorrhoids,” for I was never actually in character. While the line “I declare, it’s been a month of Sundays since I’ve seen you!” came out of my mouth, running through my head was: “Who talks that way? Why not just say, ‘it’s been a month’? The Sundays are implied.”

The only point in each performance when I felt the slightest association with how Miss Bessom might think and feel was when the Mrs. Dunbar character said to Bessom/me, “They told me you were gettin’ real fleshy.” Bottom line: I couldn’t act my way out of a paper bag if it were made of me- sized holes. Whatever, no biggie— except that every other spotter at Holmes Hi- Tech was an actor. In fact, it was a thespian friend of mine who’d introduced me to the gig. Actors liked the work because, in addition to the flexible hours, it allowed them to practice their craft. I pursued the job because it sounded cool, the closest to clandestine this suburban girl could get. I wish I were able to reveal to you a deeper, more complicated motivation— a consuming desire to serve justice, a fascination with Chinese culture, a lurid role- playing fetish. “It sounded cool” is a lame provocation, but there it is nonetheless. I’ve grown accustomed to the disappointment engendered by that response. People prefer a good story.

My actor coworkers wrote new narratives every morning. After exchanging flyer postcards for various low- budget blackbox- theater one- acts, they’d transform themselves. I remember this brunette who earned the moniker “chameleon.” She left the office once as a Canadian- accented tourist and returned that afternoon a Goth teenager, replete with pale makeup and ripped skull- and- crossbones tights. I didn’t even recognize her.

She was one of only a few who switched from one identity to another beyond the office. Our manager discouraged the practice because there was nowhere safe to do it. She also warned us not to take notes anywhere, not even in a bank or pizza shop, and not to leave information on voice mails within earshot of anyone. She’d lost two spotters that way, one who’d blown his cover in front of an employee at Pearl Paint, and another who’d done so next to an elderly man playing mah- jongg in Columbus Park. Our manager said everyone in Chinatown was involved, “Everyone is in on it.” Obviously, that’s egregious hyperbole, but I think what she meant to say was that there was no establishment at which we could be certain no one was involved. Indeed, I once happened across a multi- thousand- dollar phony- Rolex deal while hitting the loo at the Lafayette Street Holiday Inn.

The most convincing performers scored the respected roles. One time, during assignments, our manager told this guy Henry that she’d be helping with his disguise that morning. Authenticity was critical, as they needed him to case a location for four straight hours, to monitor who came and went. So Henry became a junkie. He passed the afternoon sitting or standing on the curb, intermittently nodding off. Back at the office, while demonstrating the smackhead lean, wherein the body reaches an angle nearly 45 degrees but somehow, Newton defyingly, does not fall, he explained that he’d delivered a depiction so convincing, it’d attracted the attention of both a cop, who told him he was disorderly and threatened to arrest him, and a born- again Christian, who told him about Jesus and threatened to save his soul.

And then there was I, approaching the disguise closet each time with only this question: Which wig today, the brown one that resembles my actual hair? Or the brown one that’s exactly like my actual hair? After the great Miss Bessom debacle, I knew better than to try to act like someone else. Also, I’m a terrible vocal mimic. I can’t even ape midwestern, and that’s the O- negative blood type of accents: It can flow through anyone. It’s the Bill Cosby impression of accents. And I am also bad at those . . . unless what’s been requested is “Bill Cosby doing a Japanese man.”

So only two characters lived on my résumé. One was me, and the other was a heightened version of me, the me I imagined I’d be if I’d stayed in North Carolina. Alterna- Me had, for starters, a much thicker drawl, which I could pull off because rather than “doing an accent,” I merely tapped into the way I sound when I’ve had too much to drink. She was young, married, and applying to law schools near her home in Raleigh. She wore pearls and belonged to things like supper clubs and congregations. She grocery shopped at the Harris Teeter and ate lunch on Sundays at the Carolina Country Club. If ever questioned, I could have recited her biography easily. I knew everything about her, even though I am not the one who created her.

“Don’t you want to come home and go to law school?” my uncle Lucius used to ask nearly every time we spoke. “Raleigh’s nice, you know. It’s ranked on the list of most livable cities.”

“I’ll throw a luncheon for you!” Aunt Jane, for whom I am named, would add, having picked up another phone in the house. “And get you into all the clubs.”

“You can join the Episcopal Church.”

And then my aunt would shout, “I’ll give you all my jewelry!”

So, yeah, this girl was a big part of my life. And somehow, she worked. I canvassed Canal Street three, occasionally four times a week, always wearing a shade of the same person, and got away with it. I didn’t need to be a chameleon because the counterfeiters bought me. Eventually, I developed a theory regarding why. Since they knew how we operated, merchants were suspicious of every potential customer, scrutinized each for tells that he or she might be a spy. I noticed them paying special attention to certain people while ignoring others, whomever they could quickly disregard as guileless. I never needed to become a different person, as long as the original was consistently overlooked. And as I’ve come to understand, people— from, apparently, either hemisphere— assume Southerners are innocent.

It was a wondrous thing to witness. Salesmen eyed me warily until the moment I purred, “Y’all got Gucci?” when they’d instantly drop their guards and either lift a sheet, pull a trash bag from a desk, or open a concealed door in a false wall. It’s not as if we were suddenly pals; there were no smiles or secret handshakes. What happened was a dismissal. They dismissed me, shifted mentally from looking at me to looking beyond me, over my shoulder for the next potential threat.

Astute readers would argue that any accent could have put them at ease. And for the most part that’s true. Counterfeiters trust tourists. But I’m telling you, there’s something foolproof about the drawl. Unlike some of the other spotters, I was almost never denied access. I can only posit that Barney Fife and Elly Mae Clampett exist in the collective unconscious, because I don’t think Mao fed his starving republic on a diet of TV Land classics. Which is to say that maybe it was more than the accent; maybe it was also my accompanying wide eyes and gullible smile. Come to think of it, maybe it was I who worked like a Southern charm.

Once, I asked a peddler if he had “LV” in the store and he whispered, “Not now.”

“Why?” I responded vapidly. He nodded toward another woman. “Come back later when she’s gone. She pretends to shop, but she’s a spy.”

Whoever she was, she didn’t work for us. Possibly she reported to Customs, but I doubt it. Either way, a moment later he threw her out of the store so that I, the spy, could shop. Not only did he fail to suspect me, he shared delicate information! My countenance and personality telegraphed a prodigious naïveté. It’s a circumstance discouraging and frustrating, and I didn’t mind at all using it against them. Still, even with my airtight Hee Haw avatar, I couldn’t get cocky. A couple of times during my stint with the firm, coworkers returned from a day on the streets and heard, when the elevator opened, “You’ve been burned.” Our manager knew immediately because she had informants on the inside. That was a spotter’s worst day of work and also his or her last. It’s kind of like accidentally firing yourself.

Typically, though, the response was, “I figured.” An agent knows when the jig is up. If you approach a shop and it closes its gates, you’ve been burned. If you turn around and a shopkeeper you’ve been watching is following to see where you’re going, you’ve been burned. If passing one of the sentinel lookouts, who stand on stools at major intersections in Chinatown during the highly trafficked weekends, leads him to reach for his mobile phone and set off a chain reaction of cellular warnings that runs down Canal Street like those mountaintop bonfires in The Return of the King, you’ve been burned.

Game over.

In other words, I couldn’t work every day. But it was summer, and in your twenties, that means weddings, which require plane tickets, gifts, and for me, that summer, two bridesmaids dresses. I was behooved by teal-green ruffles to seek supplementary employment. I picked up temp work here and there. And because I had experience waiting tables in college at a wing joint called Pantana Bob’s— for which I wore a T- shirt that read “Bob’s Got a Big Deck!”— I scored one shift a week at the legendary West Village brewpub Chumley’s.

It was cush. The owner promised a set amount each shift, so if my tips were short, he’d pay out the difference from his pocket; decent guy. He rarely had to, though. The place stayed packed. Both locals and tourists competed to sit in a booth that might have been occupied by John Steinbeck, Jack Kerouac, Simone de Beauvoir, F. Scott Fitzgerald, J. D. Salinger, Willa Cather, e.e. cummings, William Burroughs, Norman Mailer, Ernest Hemingway, Edna St. Vincent Millay, or any other of the dozens of literary luminaries who are said to have haunted the windowless speakeasy either during or after its Prohibition heyday. It didn’t matter that flies swarmed the back room, the jukebox featured only opera, or that sawdust inevitably found its way into your overpriced shepherd’s pie and frequently flat beer. With a pedigree such as that, derelictions are deemed charming. I agreed. I loved the joint.

I discovered the venerable institution through Lou, the elder of my two older sisters, who lived in the West Village when I arrived in New York. She and her friends, many of whom went to college with her, took me under their collective wing as the kid sister they knew me to be— emphasis on kid. Lou and I are seven years apart, so those college pals hadn’t seen me since the perm. Actually, Lou and I hadn’t seen much of each other either. She left for boarding school when I was eight. Of course, we visited over holidays and family vacations, but we didn’t have a relationship outside of the family unit. It was different with my middle sister, Tucker, but with Lou . . . I spent more of my cognitive childhood imagining her than experiencing her.

I remember trying to picture her New York apartment. In my mind, it had a tree- lined street and simple concrete stoop. I’d visualize ascending a dark and steep stairwell; I could see myself opening the door. I knew the layout of the fictional furniture and the color of the imaginary couch.

Of course, her real apartment was completely different, and hilariously smaller— particularly when, in addition to her and her roommate, I was there, which was all of the time. I’d come over to watch TV, or have a glass of wine, or just because I could. The first time we ordered takeout, I painstakingly separated out the duplicate menus in order to beef up my collection uptown, before Lou explained that New York restaurants don’t deliver beyond their immediate area: “Did you think they’d get on the subway with your pad thai?”

She teased me a lot, but mostly she mothered me, which I guess I needed at the time because why else would I think it was OK to sleep over in her tiny double bed, like, once or twice a week? I would have hated me. She gave me a key, and occasionally I’d let myself in at three in the morning, when they were both asleep, have a snack, open Lou’s door, and ask her to “scoot over.” But most of the times that I stayed were on nights when we’d been out together carousing in her neighborhood joints. Everywhere in the West Village was legendary. We went to Corner Bistro for the best burgers in the city, and to the White Horse Tavern, where Dylan Thomas drank himself to death. Lou and I stood in line for cupcakes at Magnolia Bakery and caught a scene of Sex and the City being shot on her block.

When my lease was up in August, I decided to move to the corner of Perry and Hudson streets. My friends thought I was crazy; the apartment on Eighty- Seventh was a block from Central Park, had a private garden with a tree and a hammock, and my portion was $300 less a month than I’d be paying on Perry. Why was I moving to the West Village?

“I don’t know,” I said and shrugged my shoulders. “Sounds cool.”

Unfortunately, Lou wasn’t there anymore. She’d moved back to North Carolina the month prior. She lived in New York for seven years, but we overlapped for only one. Oh well, at least she’d had a chance to show me the ropes, for example, how to get into

Chumley’s.

The main entrance was hidden in the back of a courtyard on Barrow Street, and the back door was unmarked at 86 Bedford; during Prohibition, when a bribed cop called to warn the barkeep of an ensuing raid through the courtyard, the crowd was instructed to exit on Bedford, or to “ eighty- six it,” which is the origin of that famous idiom. Patrons could also escape through a secret bookcase that led to an alley. Apparently, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre consummated their marriage in one of the booths. And it’s where James Joyce wrote Ulysses.

Oh geez, oops: I’m lying again. Sorry: you’re not diners. I guess, while working there, it became second nature. Those stories, and a dozen others phonier than a character in The Catcher in the Rye, were tossed to patrons thirsty for more than a pint. I heard some of them from other servers, a few from the walking- tour and bar- crawl guides who led their keeps inside, and most from curious patrons who’d picked up the apocryphal trivia elsewhere: travel books, blogs, drunkards at other neighborhood haunts. Everyone was in on it.

Here’s the truth. There is an entrance at 86 Bedford, but the phrase “eighty-six it” had been in use— and in print— long before Chumley’s opened. There was also a secret bookcase, but it went to the kitchen. And it’s pretty well documented that James Joyce wrote Ulysses in Zurich and Paris. As for the young Fitzgeralds . . . I can’t prove they didn’t . . . and they were married in New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral . . . but still, sometimes you have to trust your gut, and mine thinks even Gatsby and Daisy wouldn’t have boinked in a pub. As one of the walking- tour guides put it, “Writers are known to get drunk and embellish.”

No one set out to spread distortions. It started innocently. In fact, I believed the tales myself until a fellow employee laughed at one of my questions and asked, “You do know that half of those stories are false?” But then, it became hard to stop— particularly when customers asked leading questions. One wanted to know if the ladies’ room had once been a dumbwaiter that carried people to a gambling den on the second floor. Another had heard that, actually, the dumbwaiter went to the basement and was how they carried the booze inside. Or, according to someone else, that’s what the trapdoor was for, since it connected to a tunnel that led to the rum- delivering boats. Still others pointed to that door in the floor and told their friends, “Runaway slaves used to climb through that hole because when this was a blacksmith’s shop, it was a stop on the Underground Railroad.”

And then they’d look up at me, all of them, with eager eyes, and ask, “Isn’t that right?”

Um, er, thwlllpb, “Sure is! Neat, huh?” Tell them what they want to hear. The only time I didn’t play along, I instantly regretted it. While I distributed menus, a father told his children that this had been where Dylan Thomas died.

“Actually,” I piped in, “you’re thinking of the White Horse.” His face sank, and so did his children’s. What had I achieved? What mattered more: verifying a useless fact or giving them a memorable meal— one whose imagined worth exceeded the menu’s prices? Besides, I can’t say for sure that Thomas didn’t stop by Chumley’s for one round before heading to the White Horse, just as it’s impossible to prove that the blacksmith shop wasn’t part of the Underground Railroad, or that the bookcase hadn’t, at one point, led to the street. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “Sometimes I don’t know whether Zelda and I are real or whether we are characters in one of my novels.”

And anyway, Dylan Thomas died in St. Vincent’s Hospital. So from that point forward, I just said yes to all of the legends. “I heard Fitzgerald wrote Gatsby here.” He sure did, and in fact, you are sitting in the same booth. “Is it true that R.F.K. sketched out his

presidential campaign platform in this bar?” Yeah, and would you believe it was in this exact booth! You could have asked me anything. Did William Burroughs name Naked Lunch after Chumley’s BLT? Is that the barstool where e.e. cummings gave up capital letters? Is this where a blind John Milton dictated Paradise Lost to his amanuensis? You bet, and I don’t want to blow your mind, but it was in this very booth.

Wait a second, the fictional you is thinking, Milton died before the West Village existed. Sure, but didn’t you know that the dumbwaiter in Chumley’s was once a time machine? After escaping entrapment in the Pokémon- sheet cave, I cut down a block and moved swiftly on Walker Street toward the center of Chinatown, intuiting that my next assignment would be on the west end of Canal, where no one had seen me yet, and knowing that I’d need to reach it before the news of the last raid did.

I called the office for the target and sure enough, it was still several blocks away. When I arrived, the goods on display were all anonymous, legal. I feared it was too late, but I milled about regardless. A middle- aged woman standing nearby solicited advice about a wallet she considered.

“I can’t believe it’s real leather for this cheap,” she giggled in a thick Long Island accent.

“It’s not real,” I told her, maintaining my harmless Southern drawl, but unable to disguise the skepticism.

“But it says so on the wallet,” she said incredulously.

“That doesn’t mean anything.” I don’t know why I chose this battle. I guess, sometimes I was bothered less by the counterfeiters—even though they annually steal around one billion tax dollars from New York City, support a system of illegal-immigrant indentured servitude, and occasionally fund terrorism— than I was by the willful naïveté of the bargain hunters. How could she believe that piece of junk was real? Were we looking at the same wallet? It had a plastic sheen. The stitching wasn’t even in straight lines. At this point, she shouted across the store to the vendor, intent on settling the dispute: “Is it real?”

“Of course,” he said, “it says so on the label.”

She looked up at me and actually said, “I told you so.”

Whatever, I thought. You are not my child. Then I saw a man walk out of the back room with a thirty-gallon trash bag slung over his shoulder, and instantly stopped caring about the fool from Long Island. It wasn’t too late after all. They’d merely removed the contraband from the front room; only now were they excising it from the premises. I felt my heartbeat accelerate as I casually spun my back to him, a move that also allowed me to see which way he turned outside the door— I would have to follow. Then I flipped through the “real” wallets one more time, giving him a several- second head start, and pursued the tail.

Following people was the only time I didn’t feel completely confident and comfortable on the job. When gathering intelligence, I could come and go as I pleased, depending on who was or wasn’t looking. But while tailing a mark, I couldn’t cut my own path. And I feared that would draw suspicion, betray me; no two people follow the exact same path. I maintained a generous distance between us as we headed east, and I called the office to alert the raid team of a change in plans. On the other side of Broadway, he crossed south on Canal and then did what I’d feared he would seconds earlier: took a right on Cortland Alley. No one walks through Cortland Alley. It’s a narrow passage that spans two blocks and has no storefronts. You might recognize it from appearing in movies whose scripts call for an alley that no one walks through. It is not the sort of grimy, dark, vermin- infested, less- traveled road down which a prim, tomato- pie- making, y’ allspewing gal from the sticks would, on a whim, mosey.

True to its nature, this morning Cortland Alley was empty. I lingered on the corner of Canal before turning, aiming to diminish the amount of time we’d be alone on the block, but I had to enter: The distance to the next intersection is long enough that if I waited until he arrived at it, and he turned, he’d have had an opportunity to turn again before I arrived, and I would’ve lost him for good. So I joined.

He never looked back. I reminded myself that criminals are dumb. After a few more blocks, he led me not to another handbag store, which was typically the case as ringleaders control several locations, nor to a warehouse- like storage facility, which is how we made the occasional major bust, but to a small innocuous food market on a side street. Everyone is in on it.

He nodded to a guy, who nodded back and then led him through a door behind the counter. I grabbed a produce baggie. The room was redolent of fish alive, dead, dried, and dying. Every piece of text contained within was written or printed in Chinese. I was the only Caucasian inside and desperately tried to appear as if I had a reason to be, as if I’d come for something specific. That ended up being three stocky white root vegetables, the least unfamiliar items for sale. Burdock? Parsnip? I have no idea what I fried and ate that night.

Confident that the contraband would not move again, I left the market and called in its address to my manager. When I met the team that night at the Irish pub, I heard they’d rolled into the grocery with a warrant an hour after I left. The bags were exactly where I’d said they’d be. Somebody bought me a beer.

The next day I worked at Chumley’s, slinging burgers and returning beers when they became flies’ watery graves. But the day after that I was back in Chinatown. I should’ve waited longer, let things cool. I cased a few stalls: usual shtick, usual scores. And then, near the intersection of Canal and Centre, a man in a baseball cap caught my eye and held it for a millisecond longer than I expected him to.

I felt it immediately. I continued in the same direction at a casual pace for a block and a half, and then looked over my shoulder. Sure enough, he was behind me— talking on his cell phone. To confirm what I already knew, I popped into another storefront or two, but, wouldn’t you know: No one was selling knockoffs anymore that day, not even when I batted my eyelashes, drew out my “i”s, and talked about Jesus.

Returning to the office, I expected a burn notice, but when the elevator doors opened all I heard was, “Hey Jane.” It’s possible I was wrong but . . . there’s no way I was wrong. An agent knows. I must’ve blown my cover in the grocery; Baseball Cap must have been in that market.

On Canal Street, I drew no suspicion, because I looked like a tourist, sure, but also because the salesmen had an incentive to believe I was who I said I was: They wanted to sell bags. Just like the fool from Long Island believed the wallets were real because she wanted to have found a deal on a luxury item. It was the incentive that had made me a good spy— not my own work— and no one in the grocery store had it. They saw my syrupy Southern- tourist persona for what it was: a knockoff unraveling at its haphazardly stitched seams.

I was too ashamed to tell my boss, so instead I removed my name from the remainder of the schedule and left. Not long after that, upon entering my apartment building on the corner of Hudson and Perry, I walked upstairs and stuck my key in the lock, but it wouldn’t turn. Duh, I thought, as I instantly realized my gaffe: wrong floor. I deduced the error quickly because I was familiar with the mistake; I made it about once a week that year. It was a strange and annoying affliction that has never struck me in any other of my many dwellings.

My place was on the third floor, first door at the top of the stairs. Sometimes I stuck my key in the right lock. Other times I tried to open the corresponding door on the second floor, and sometimes even the one on the fourth. My neighbors never said anything; I was mostly a nuisance to myself.

In this particular instance, however, after recently being burned, the pattern played out a little differently. When I yelled at myself in my head— Geez, it’s like you’re a tourist in your own home!— I saw that I was. The West Village wasn’t home. I realized that I didn’t even like it that much. In fact, I generally hung out in the bars and restaurants of other neighborhoods. I’d hardly decorated my room.

The apartment felt counterfeit. So I started thinking backward. If this seemed obvious now, but I hadn’t noticed any of it before, then my ignorance must have been willful, which means I’d had an incentive— one whose imagined worth was so great, I’d gone more than $4,000 in debt paying rent in a neighborhood I couldn’t afford.

OK, here is where I tell you that I lied one last time. The truth is this: I do know why I moved to the West Village. I was chasing Lou. Finally, finally I’d reached her, and suddenly she was gone again. But in the legendary West Village, I could retrace her steps. Whenever I fancied, I could pop into Magnolia for a chocolate cupcake or go dancing at Automatic Slims. I could eat burgers at Corner Bistro and tell myself with eager eyes, “I bet Lou sat here once . . .in this very booth!”

I had spent so many years imagining her before, it was easy to slip back into the habit. But I wasn’t chasing her; I was chasing her narrative, trying to consume her authentic experience— an inherently inauthentic pursuit. No two people follow the exact same path. And I couldn’t even be certain the narrative was true. I’d cobbled the account together from anecdotes apocryphal and embellished by drink. I had the right key but it was in the wrong lock. If the world is made of narratives, then it was time I write my own.

And I may as well start from the beginning.

Recenzii

"What is it about North Carolina? First they gave us David Sedaris. Now they’ve produced Jane Borden. She’s charming, polite and, yes, very funny."

—A.J. Jacobs

"The classic story of Country Club mouse meets City mouse, a sweet reminder of what it feels like to be new in New York."

—Amy Poehler

"If you took Mark Twain, shaved the mustache, added lady parts, and dropped him in present-day Manhattan, he’d wind up writing this fabulous book. Instead, the universe provided Jane Borden, who nailed it."

—Ed Helms

"Reading this charming and zany debut, I just wanted to hug Jane Borden. Out of all the North Carolina greenhorns who ever navigated the funky streets of 21st century New York, she may be my favorite. And she can write a sentence too!"

—Gary Shteyngart, author of Super Sad True Love Story

"I love how sincere Jane is while being every bit as funny as comedy writers who are detached and ironic. This is a deeply personal and hilarious love letter to both New York City and the south. I never thought I'd say those words."

—Mike Birbiglia, author of Sleepwalk with Me and Other Painfully True Stories

—A.J. Jacobs

"The classic story of Country Club mouse meets City mouse, a sweet reminder of what it feels like to be new in New York."

—Amy Poehler

"If you took Mark Twain, shaved the mustache, added lady parts, and dropped him in present-day Manhattan, he’d wind up writing this fabulous book. Instead, the universe provided Jane Borden, who nailed it."

—Ed Helms

"Reading this charming and zany debut, I just wanted to hug Jane Borden. Out of all the North Carolina greenhorns who ever navigated the funky streets of 21st century New York, she may be my favorite. And she can write a sentence too!"

—Gary Shteyngart, author of Super Sad True Love Story

"I love how sincere Jane is while being every bit as funny as comedy writers who are detached and ironic. This is a deeply personal and hilarious love letter to both New York City and the south. I never thought I'd say those words."

—Mike Birbiglia, author of Sleepwalk with Me and Other Painfully True Stories