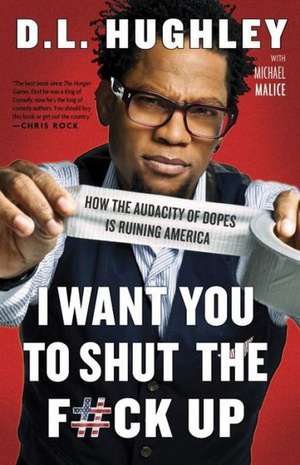

I Want You to Shut the F#ck Up: How the Audacity of Dopes Is Ruining America

Autor D. L. Hughley, Michael Maliceen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 aug 2013

“I believe America is the solution to the world’s problems.” —Rush Limbaugh

“SHUT THE F#CK UP.” —D. L. Hughley

The American dream is in dire need of a wake-up call. A f*cked up society is like an addict: if you are in denial, then things are going to keep getting worse until you hit bottom. According to D. L. Hughley, that's the direction in which America is headed.

In I Want You to Shut the F*ck Up, D.L. explains how we've become a nation of fat sissies playing Chicken Little, but in reverse: The sky is falling, but we're supposed to act like everything's fine. D.L. just points out the sobering facts: there is no standard of living by which we are the best. In terms of life expectancy, we're 36th--tied with Cuba; in terms of literacy, we're 20th--behind Kazakhstan. We sit here laughing at Borat, but the Kazakhs are sitting in their country reading.

Things are bad now and they're only going to get worse. Unless, of course, you sit down, shut the f*ck up, and listen to what D. L. Hughley has to say. I Want You to Shut the F*ck Up is a slap to the political senses, a much needed ass-kicking of the American sense of entitlement. In these pages, D. L. Hughley calls it like he sees it, offering his hilarious yet insightful thoughts on:

- Our supposedly post-racial society

- The similarities between America the superpower and the drunk idiot at the bar

- Why Bill Clinton is more a product of a black upbringing than Barack Obama

- That apologizing is not the answer to controversy, especially when you meant what you said

- Why civil rights leaders are largely to blame for black people not being represented on television

- Why getting your ghetto pass revoked should be seen as a good thing, not something to be ashamed of

- And how hard it is to be married to a black woman

Preț: 105.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.22€ • 21.03$ • 16.69£

20.22€ • 21.03$ • 16.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307986252

ISBN-10: 030798625X

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 030798625X

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Recenzii

“I Want You to Shut the F#ck Up is the best book since The Hunger Games. First he was a King of Comedy; now he's the king of comedy authors. You should buy this book or get out the country because D. L. stands for ‘don't lie,’ and he doesn't in his amazing new book.” --Chris Rock, CEO & President of NOTHING!

“I always knew it wouldn’t take a politician, a preacher, or even a scholar to solve the problems of this country. I knew it would take someone who used comedy, common sense, and a lot of cussing. D.L. has risen from a King of Comedy to a higher calling: D.L. for President 2016? Both he and this hilarious book on how to get past the B.S. get my vote!” —Tom Joyner

“[Hughley] has starred in shows on ABC (The Hughleys), CNN (D.L. Hughley Breaks the News) and HBO (Unapologetic) in addition to radio (The D.L. Hughley Morning Show), and now he finds a solid footing on yet another plateau as he makes an easy transition to the printed page….In the closing chapter, he concludes, “Comedy might not be able to change minds—but it can certainly expose truths and knock down fallacies.” Ditto for this book, which provides that much-needed wakeup call.” ߝPublishers Weekly

“Hughley’s a hard-line pragmatist whose brash opinions almost always transcend polarized black/white and liberal/conservative comfort zones. [I Want You to Shut the F#ck Up] is a solid combination of a street-tough attitude and a keen grasp of social and political hot-button issues.” --Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.

“I always knew it wouldn’t take a politician, a preacher, or even a scholar to solve the problems of this country. I knew it would take someone who used comedy, common sense, and a lot of cussing. D.L. has risen from a King of Comedy to a higher calling: D.L. for President 2016? Both he and this hilarious book on how to get past the B.S. get my vote!” —Tom Joyner

“[Hughley] has starred in shows on ABC (The Hughleys), CNN (D.L. Hughley Breaks the News) and HBO (Unapologetic) in addition to radio (The D.L. Hughley Morning Show), and now he finds a solid footing on yet another plateau as he makes an easy transition to the printed page….In the closing chapter, he concludes, “Comedy might not be able to change minds—but it can certainly expose truths and knock down fallacies.” Ditto for this book, which provides that much-needed wakeup call.” ߝPublishers Weekly

“Hughley’s a hard-line pragmatist whose brash opinions almost always transcend polarized black/white and liberal/conservative comfort zones. [I Want You to Shut the F#ck Up] is a solid combination of a street-tough attitude and a keen grasp of social and political hot-button issues.” --Kirkus

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

D.L. HUGHLEY is one of the most popular and highly recognized standup comedians on the road today. D.L. serves as a weekly contributor to The Tom Joyner Morning Show. D.L. hosted his own late night talk show on CNN, D.L. Hughley Breaks the News. Recently, D.L. starred in his own one-hour special (his fourth for HBO) entitled Unapologetic. As the star and producer of his namesake television show that ran on ABC and UPN, The Hughleys, D.L. is also well known as one of the standout comedians on the hit comedy docu-film The Original Kings of Comedy. He is a regular on the late-night talk show circuit, including appearances on Real Time with Bill Maher, The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and Conan. He has even guest-hosted on such shows as The View and Live with Regis & Kelly.

Extras

chapter 1

Let us begin by committing ourselves to the truth to see it like it is, and tell it like it is.

—Richard Nixon

If only Uncle Sam could see us now.

He’d roll up his sleeves, ball his hands into fists, and knock some sense into this nation of ours. But he’s not around, so someone else has to take the mantle. Some other proud American has to tell this country what it needs to hear. Everyone else is telling it what it wants to hear—and that’s not the path to progress.

When I was growing up, there used to be simple rules that we’ve now forgotten. The rules served us well, and they were easy to understand and follow. You do this, and you get that. You don’t do this, and you don’t get that. It was just a matter of quid pro quo.

My mother constantly used to tell us, “Don’t nobody owe you shit. You think the world revolve around you? It don’t,” or, “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” When’s the last time an American missed a meal? When did he doubt that he was the center of the universe? If I came home and told my mother that I was hungry, she’d inevitably ask me what I did that day.

“Nothing,” I’d admit.

“Well strangely, that’s what’s for dinner!” To hell with pork; nothing was the other white meat for me.

Back then, it was experience that was the best teacher. Parents used to say, “I can show you better than I can tell you.” When we were growing up and went by the stairs, all you would hear is Bump, bump, boom! And your mother would go, “Uh-huh. A hard head makes a soft ass.” Meaning: Being a stubborn troublemaker leads to many a spanking—paternal or gravitational. But these days, parents spend a lot of time babyproofing their homes. They put foam on corners, a gate by the stairs, and plastic over the outlets. The kids don’t learn what it means to fall down and hurt themselves.

Every black adult I know has a scar from doing some shit they weren’t supposed to be doing or from fucking with something they weren’t supposed to be fucking with. I was jumping up and down on the bed when I was about five years old. Sure enough, I fell and split my eyebrow open. My mother came into the room and saw me wounded. All she said was, “You know now, don’t you?”

“Mama, I’m bleeding!”

“Blood lets you know when you fucked up.” There was no wringing of hands, no “Oh, my poor baby!” No, my mother was mad. “Now I gotta take your silly ass to the hospital. If you had just listened to me and settled the fuck down, I could have been making us dinner!” I was hurt, but I learned. Our communities are hurting, but they sure as fuck ain’t learning. From an early age, we’re not even being taught how to learn.

I only stumbled upon how to learn when I was in fifth grade. That’s when I had a hippie teacher named Mr. Boston. He had long hair, a beard, and drove a Volkswagen. Mr. Boston loved listening to fucking hippie music, and he told us all about it. He loved karate, which he taught to us kids. I don’t know how effective karate was supposed to be in a neighborhood where everyone is coming heavy, but it sure gave him peace of mind. Whether it was the martial arts or the shitty songs, he wasn’t scared of our neighborhood.

Mr. Boston was one of those teachers that always went the extra mile. Unfortunately, that was often actually the case. He would drive out of his way to kids’ parents’ houses and tell on all the shit that was going down at Avalon Gardens Elementary. Every time I’d get in trouble, he’d be over. My father would have his van parked, and then Mr. Boston would park his little Volkswagen as far up as he could get it on the driveway. Whenever I saw the edge of that Volkswagen sticking out of the driveway, I knew shit was going to get fucked with. He would tell on me all the time.

One day I couldn’t follow what Mr. Boston was talking about during the lesson. I raised my hand to ask him what he meant. As soon as my arm was up in the air, I remembered how my mother yelled at me when she grew sick of my pestering her. “Oh, I’m not supposed to ask you why,” I said, under my breath. The comment was meant more for myself than anybody else, but Mr. Boston heard me.

“Always ask why,” he told me and the entire class. “You can always ask why. Any time you don’t know something, you’re supposed to ask why. Always question what somebody tells you.”

It was the most empowering thing I had ever heard in my life up until that point. My mother may have given me life, but Mr. Boston gave me thought—or rather, he gave me permission to think. He taught me the basis of learning, and it sure as fuck ain’t opening your mouth before you know the facts. From that day and even until now, it was like a switch was flicked in my mind. I knew that I had something. I didn’t know what and I couldn’t tell what would happen as a consequence, but I knew that something had gotten unlocked.

So when I hear someone spouting nonsense, I don’t just disagree—I ask why they’re doing that. When I witness Americans choosing self-destruction, I ask why. Why is this country on the wrong track? Why are we repeating the same mistakes over and over? Why are we so oblivious? It was my MO my entire life. That in itself was enough—until I became a father myself.

# # #

I was working sales at the Los Angeles Times in 1986 when my wife, LaDonna, got pregnant. My $4.75 an hour wasn’t going to cut it, so I needed a raise. Getting a promotion to sales manager required a college degree. Having just gotten my GED, a college degree was not an option. I did the next best thing: I hustled. A dude I knew had connections in the dean’s office at Long Beach State. I paid him $200, and he got me a sterling letter on official letterhead claiming that I was just a few credits away from getting my diploma.

My supervisor, a cat by the name of Ron Wolf, knew that I was full of shit and that the letter was a lie. But he took a chance on me and made me an assistant sales manager anyway, earning $30,000 a year. That was as much as a cop. I excelled so much at my gig that nine months later, they made me a full-fledged manager. A year and a half after that, they put me down in Ventura as the sales manager. I was in charge of the telephone managers, the assistant managers, and the detail clerks. In total I had eight managers and a sales staff of three hundred overseeing Ventura, Santa Barbara, Lompoc, and Santa Maria. In other words: white, ivory, vanilla, and snow white.

My region was known as the “goal post,” since it had never made goal when it came to sales. I was the youngest sales manager in the history of the Times, and the first one to be black. I guess they thought I could do something different. But apparently some of the staff didn’t want to do something different. When I walked into my office on my very first day, there was one of those black mannequin heads for displaying wigs. In case I didn’t get the message, the note attached said, go home nigger. I wasn’t shocked. Hell, I’d been called a nigger all my life. What shocks me is when people think we’re a post-racial society. Obama’s election was fueled by his race. The opposition to him is fueled by race—and the deference to him by his own people is also fueled by race.

I stepped out of my office and called out to the entire sales floor. “I don’t know who you all think you’re scaring,” I said, “but I’m not leaving. I’m not scared. I’m going to step out. When I come back, I want this wig head off my desk.”

I did just like I said, and when I came back, the wig head was off my desk. The Times sent its security force down from L.A. to investigate. “I got it,” I told them. “I’m fine.” And I was fine. I had a kid to take care of, and a new house. I just had to hustle that much harder. Three months after I started, the area made goal for the first time. For the next year straight, we kept making goal. As a reward, the paper sent me on free trips—with all these old white Times dudes who hated me. It was a gas.

I was psyched that I could come through after Ron took a chance on promoting me. But he never got excited. “Don’t get drunk on the numbers,” he told me. “Don’t ever believe it. You’re never as good as you think you are, or as bad as people say you are.” Ron always had these little sayings. It was like Yoda and Confucius had a kid who happened to be a middle-aged white dude.

This is around the time when I started doing stand-up. I would do my job in Ventura, then drive to host comedy shows in the suit and tie I wore for work—and I never stopped wearing them to this day. The thing is, these comedy clubs were not in white Ventura or in ivory Lompoc. I had to drive about three hours each way to get there. Obviously it was going to catch up to me at some point—which is why I passed out onstage one night, between Jamie Foxx and a bunch of other young comedians.

Immediately they took me to the doctor. “You didn’t pass out,” the doctor told me. “You fell asleep. You’re not getting any REM sleep, and you’re exhausted. You need to take some time off of work to rest.”

I was a manager so I still got my salary—and still did my shows. I came back to the doctor after a while, still out of it. “You still haven’t gotten your sleep,” he told me. “I’m going to take you off another couple of weeks.”

I got put on long-term disability at work, which meant that I’d be able to collect my salary for six months as long as I checked in with the doctor. That gave me time to focus on my stand‑up career. Even though I was still getting a check from the Times, LaDonna and I now had a new kid to feed. Buying a house had taken all of our money. The only place that was regularly hiring black comics at the time was not-so-white Atlanta.

One day, Ron called my wife to check up on me when I was across the country performing. LaDonna is the worst fucking liar ever. She tried to make excuses, but Ron saw right through it. Hell, he saw through my college-letter bullshit, so LaDonna didn’t really stand a chance. “Darryl’s not there, is he?”

“No!” LaDonna blurted out—and hung up the phone.

When I came back to work to report what was happening with my disability, Ron took me aside. He knew that I had been doing stand-up, and that I was just trying to do what I could to launch my career while taking care of my family at the same time. He knew all this, and he understood. “I’m going to keep your benefits alive for a year,” he told me, “and I’m going to keep your salary alive for a year.” He did all that and more. My bonus should have $20,000, but Ron upped it to $30,000 for making goal. If there were any issues at work, Ron ran interference for me while I was gone pursuing my dreams. That window of time was what I needed to make it as a successful stand‑up comedian, and the rest was history—or so I thought.

In 2005, I was playing a gig in Canyon Country. Ron came with his new wife. I hadn’t seen him in years, so it was really cool to catch up after all that time had passed. When he went to get us a round of drinks, his wife could not help but gush. “He is so proud of you,” she told me.

I admit it, that made me smile. “Man, that is so nice.”

“You know, he lost his job because he gave you that bonus.”

I could not believe what she was telling me. “What? He did?”

“Yeah. He got fired because he gave you that discretionary bonus and because he kept your benefits alive for that long. Then he got divorced. He totally hit rock bottom. It was a while before he got back on his feet.”

I was in shock. When Ron came back to the table with our drinks, I had to find out what happened. “Ron, my man, did you lose your gig because of me?”

“Forget all that. Let’s talk about something else.” And that was that.

From then on, Ron and I stayed in touch and would talk on the phone from time to time. Eventually, though, I had to find out the truth. “Man,” I said, “I gotta ask you why you did that.”

“Why I did what?”

“Why did you jeopardize your career, your marriage, your everything for me?”

“Well, first off,” he said, “if I had known that was going to happen, I wouldn’t have done it. But I just knew you had something. I knew you did.”

“Man, I can’t thank you enough. I was grateful then and I am grateful now.”

Then Ron, the middle-aged white dude who happened to be the son of Yoda and Confucius, dropped another one of his sayings. “Every time you’re onstage,” he told me, “you have the obligation to tell the truth. Be truthful, be straightforward. Never be afraid for people not to like you.”

Even though Ron had gotten hired back at the Times and had found a new wife, for a while the dude had lost it all because he believed in me. That’s why I take what I do so seriously and say what I mean and mean what I say. That’s why it’s not enough for me to ask why. It may sound funny, but to me this shit ain’t no joke. When I’m onstage, when I’m on the radio, when I’m doing an interview, I have to call it like I see it.

Let us begin by committing ourselves to the truth to see it like it is, and tell it like it is.

—Richard Nixon

If only Uncle Sam could see us now.

He’d roll up his sleeves, ball his hands into fists, and knock some sense into this nation of ours. But he’s not around, so someone else has to take the mantle. Some other proud American has to tell this country what it needs to hear. Everyone else is telling it what it wants to hear—and that’s not the path to progress.

When I was growing up, there used to be simple rules that we’ve now forgotten. The rules served us well, and they were easy to understand and follow. You do this, and you get that. You don’t do this, and you don’t get that. It was just a matter of quid pro quo.

My mother constantly used to tell us, “Don’t nobody owe you shit. You think the world revolve around you? It don’t,” or, “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” When’s the last time an American missed a meal? When did he doubt that he was the center of the universe? If I came home and told my mother that I was hungry, she’d inevitably ask me what I did that day.

“Nothing,” I’d admit.

“Well strangely, that’s what’s for dinner!” To hell with pork; nothing was the other white meat for me.

Back then, it was experience that was the best teacher. Parents used to say, “I can show you better than I can tell you.” When we were growing up and went by the stairs, all you would hear is Bump, bump, boom! And your mother would go, “Uh-huh. A hard head makes a soft ass.” Meaning: Being a stubborn troublemaker leads to many a spanking—paternal or gravitational. But these days, parents spend a lot of time babyproofing their homes. They put foam on corners, a gate by the stairs, and plastic over the outlets. The kids don’t learn what it means to fall down and hurt themselves.

Every black adult I know has a scar from doing some shit they weren’t supposed to be doing or from fucking with something they weren’t supposed to be fucking with. I was jumping up and down on the bed when I was about five years old. Sure enough, I fell and split my eyebrow open. My mother came into the room and saw me wounded. All she said was, “You know now, don’t you?”

“Mama, I’m bleeding!”

“Blood lets you know when you fucked up.” There was no wringing of hands, no “Oh, my poor baby!” No, my mother was mad. “Now I gotta take your silly ass to the hospital. If you had just listened to me and settled the fuck down, I could have been making us dinner!” I was hurt, but I learned. Our communities are hurting, but they sure as fuck ain’t learning. From an early age, we’re not even being taught how to learn.

I only stumbled upon how to learn when I was in fifth grade. That’s when I had a hippie teacher named Mr. Boston. He had long hair, a beard, and drove a Volkswagen. Mr. Boston loved listening to fucking hippie music, and he told us all about it. He loved karate, which he taught to us kids. I don’t know how effective karate was supposed to be in a neighborhood where everyone is coming heavy, but it sure gave him peace of mind. Whether it was the martial arts or the shitty songs, he wasn’t scared of our neighborhood.

Mr. Boston was one of those teachers that always went the extra mile. Unfortunately, that was often actually the case. He would drive out of his way to kids’ parents’ houses and tell on all the shit that was going down at Avalon Gardens Elementary. Every time I’d get in trouble, he’d be over. My father would have his van parked, and then Mr. Boston would park his little Volkswagen as far up as he could get it on the driveway. Whenever I saw the edge of that Volkswagen sticking out of the driveway, I knew shit was going to get fucked with. He would tell on me all the time.

One day I couldn’t follow what Mr. Boston was talking about during the lesson. I raised my hand to ask him what he meant. As soon as my arm was up in the air, I remembered how my mother yelled at me when she grew sick of my pestering her. “Oh, I’m not supposed to ask you why,” I said, under my breath. The comment was meant more for myself than anybody else, but Mr. Boston heard me.

“Always ask why,” he told me and the entire class. “You can always ask why. Any time you don’t know something, you’re supposed to ask why. Always question what somebody tells you.”

It was the most empowering thing I had ever heard in my life up until that point. My mother may have given me life, but Mr. Boston gave me thought—or rather, he gave me permission to think. He taught me the basis of learning, and it sure as fuck ain’t opening your mouth before you know the facts. From that day and even until now, it was like a switch was flicked in my mind. I knew that I had something. I didn’t know what and I couldn’t tell what would happen as a consequence, but I knew that something had gotten unlocked.

So when I hear someone spouting nonsense, I don’t just disagree—I ask why they’re doing that. When I witness Americans choosing self-destruction, I ask why. Why is this country on the wrong track? Why are we repeating the same mistakes over and over? Why are we so oblivious? It was my MO my entire life. That in itself was enough—until I became a father myself.

# # #

I was working sales at the Los Angeles Times in 1986 when my wife, LaDonna, got pregnant. My $4.75 an hour wasn’t going to cut it, so I needed a raise. Getting a promotion to sales manager required a college degree. Having just gotten my GED, a college degree was not an option. I did the next best thing: I hustled. A dude I knew had connections in the dean’s office at Long Beach State. I paid him $200, and he got me a sterling letter on official letterhead claiming that I was just a few credits away from getting my diploma.

My supervisor, a cat by the name of Ron Wolf, knew that I was full of shit and that the letter was a lie. But he took a chance on me and made me an assistant sales manager anyway, earning $30,000 a year. That was as much as a cop. I excelled so much at my gig that nine months later, they made me a full-fledged manager. A year and a half after that, they put me down in Ventura as the sales manager. I was in charge of the telephone managers, the assistant managers, and the detail clerks. In total I had eight managers and a sales staff of three hundred overseeing Ventura, Santa Barbara, Lompoc, and Santa Maria. In other words: white, ivory, vanilla, and snow white.

My region was known as the “goal post,” since it had never made goal when it came to sales. I was the youngest sales manager in the history of the Times, and the first one to be black. I guess they thought I could do something different. But apparently some of the staff didn’t want to do something different. When I walked into my office on my very first day, there was one of those black mannequin heads for displaying wigs. In case I didn’t get the message, the note attached said, go home nigger. I wasn’t shocked. Hell, I’d been called a nigger all my life. What shocks me is when people think we’re a post-racial society. Obama’s election was fueled by his race. The opposition to him is fueled by race—and the deference to him by his own people is also fueled by race.

I stepped out of my office and called out to the entire sales floor. “I don’t know who you all think you’re scaring,” I said, “but I’m not leaving. I’m not scared. I’m going to step out. When I come back, I want this wig head off my desk.”

I did just like I said, and when I came back, the wig head was off my desk. The Times sent its security force down from L.A. to investigate. “I got it,” I told them. “I’m fine.” And I was fine. I had a kid to take care of, and a new house. I just had to hustle that much harder. Three months after I started, the area made goal for the first time. For the next year straight, we kept making goal. As a reward, the paper sent me on free trips—with all these old white Times dudes who hated me. It was a gas.

I was psyched that I could come through after Ron took a chance on promoting me. But he never got excited. “Don’t get drunk on the numbers,” he told me. “Don’t ever believe it. You’re never as good as you think you are, or as bad as people say you are.” Ron always had these little sayings. It was like Yoda and Confucius had a kid who happened to be a middle-aged white dude.

This is around the time when I started doing stand-up. I would do my job in Ventura, then drive to host comedy shows in the suit and tie I wore for work—and I never stopped wearing them to this day. The thing is, these comedy clubs were not in white Ventura or in ivory Lompoc. I had to drive about three hours each way to get there. Obviously it was going to catch up to me at some point—which is why I passed out onstage one night, between Jamie Foxx and a bunch of other young comedians.

Immediately they took me to the doctor. “You didn’t pass out,” the doctor told me. “You fell asleep. You’re not getting any REM sleep, and you’re exhausted. You need to take some time off of work to rest.”

I was a manager so I still got my salary—and still did my shows. I came back to the doctor after a while, still out of it. “You still haven’t gotten your sleep,” he told me. “I’m going to take you off another couple of weeks.”

I got put on long-term disability at work, which meant that I’d be able to collect my salary for six months as long as I checked in with the doctor. That gave me time to focus on my stand‑up career. Even though I was still getting a check from the Times, LaDonna and I now had a new kid to feed. Buying a house had taken all of our money. The only place that was regularly hiring black comics at the time was not-so-white Atlanta.

One day, Ron called my wife to check up on me when I was across the country performing. LaDonna is the worst fucking liar ever. She tried to make excuses, but Ron saw right through it. Hell, he saw through my college-letter bullshit, so LaDonna didn’t really stand a chance. “Darryl’s not there, is he?”

“No!” LaDonna blurted out—and hung up the phone.

When I came back to work to report what was happening with my disability, Ron took me aside. He knew that I had been doing stand-up, and that I was just trying to do what I could to launch my career while taking care of my family at the same time. He knew all this, and he understood. “I’m going to keep your benefits alive for a year,” he told me, “and I’m going to keep your salary alive for a year.” He did all that and more. My bonus should have $20,000, but Ron upped it to $30,000 for making goal. If there were any issues at work, Ron ran interference for me while I was gone pursuing my dreams. That window of time was what I needed to make it as a successful stand‑up comedian, and the rest was history—or so I thought.

In 2005, I was playing a gig in Canyon Country. Ron came with his new wife. I hadn’t seen him in years, so it was really cool to catch up after all that time had passed. When he went to get us a round of drinks, his wife could not help but gush. “He is so proud of you,” she told me.

I admit it, that made me smile. “Man, that is so nice.”

“You know, he lost his job because he gave you that bonus.”

I could not believe what she was telling me. “What? He did?”

“Yeah. He got fired because he gave you that discretionary bonus and because he kept your benefits alive for that long. Then he got divorced. He totally hit rock bottom. It was a while before he got back on his feet.”

I was in shock. When Ron came back to the table with our drinks, I had to find out what happened. “Ron, my man, did you lose your gig because of me?”

“Forget all that. Let’s talk about something else.” And that was that.

From then on, Ron and I stayed in touch and would talk on the phone from time to time. Eventually, though, I had to find out the truth. “Man,” I said, “I gotta ask you why you did that.”

“Why I did what?”

“Why did you jeopardize your career, your marriage, your everything for me?”

“Well, first off,” he said, “if I had known that was going to happen, I wouldn’t have done it. But I just knew you had something. I knew you did.”

“Man, I can’t thank you enough. I was grateful then and I am grateful now.”

Then Ron, the middle-aged white dude who happened to be the son of Yoda and Confucius, dropped another one of his sayings. “Every time you’re onstage,” he told me, “you have the obligation to tell the truth. Be truthful, be straightforward. Never be afraid for people not to like you.”

Even though Ron had gotten hired back at the Times and had found a new wife, for a while the dude had lost it all because he believed in me. That’s why I take what I do so seriously and say what I mean and mean what I say. That’s why it’s not enough for me to ask why. It may sound funny, but to me this shit ain’t no joke. When I’m onstage, when I’m on the radio, when I’m doing an interview, I have to call it like I see it.