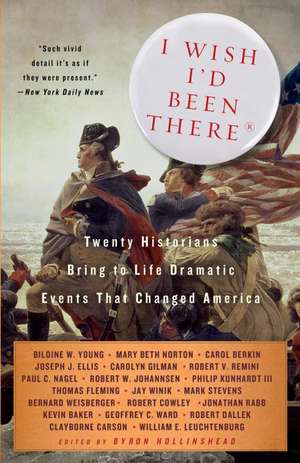

I Wish I'd Been There: Twenty Historians Bring to Life the Dramatic Events That Changed America

Editat de Byron Hollinsheaden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2007

Preț: 95.85 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 144

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.35€ • 18.91$ • 15.49£

18.35€ • 18.91$ • 15.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096541

ISBN-10: 1400096545

Pagini: 338

Ilustrații: 26 ILUSTRATIONS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400096545

Pagini: 338

Ilustrații: 26 ILUSTRATIONS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Byron Hollinshead is president of American Historical Publications, a producer of books in history for adults and for children. Previously, he was president of American Heritage Publishing Company and Oxford University Press, Inc. He was publisher of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History and Time Machine: American History for Kids. He is a former president of National History Day and, currently, vice-chair of The National Council for History Education. Hollinshead has been a consultant to several PBS documentaries in history including, most recently, Freedom: A History of US, a sixteen part series from Kunhardt Productions. As an editor and publisher, Mr. Hollinshead has worked with many of the authors in this anthology on their previous books and articles.

Extras

Biloine W. Young

A Day in Cahokia–AD 1030

Biloine (Billie) Young lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and is involved there in a number of cultural and civic activities. She is also the founder of Centro Colombo Americano, an educational and cultural center in Cali, Colombia. Among her published books are Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis; Mexican Odyssey: Our Search for the People’s Art; A Dream for Gilberto: An Immigrant Family’s Struggle to Become American; and Three Hundred Years on the Upper Mississippi. In this essay Billie Young takes an imaginary journey to the Mississippi River metropolis of Cahokia in the summer of 1030. It is an unforgettable experience.

***

A Day in Cahokia–AD 1030

One of the first discoveries made by the Spanish who came to the New World following Columbus was that the Americas were filled with people living in advanced civilizations. Cortez and his men were astounded, in 1519, at the sight of the Aztec Tenochtitlán, a city of 300,000 that was larger, cleaner, and more efficiently managed than any in Europe. The sight was so extraordinary that the superstitious soldiers thought they had been enchanted “on account of the great towers and pyramids and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry.” Houses, shaded with cotton awnings, were “well made of cut stone, cedar, and other fragrant woods, with great rooms and patios, all plastered and bright.”

The Europeans would have been even more amazed if they had known that five hundred years earlier the Indians of North America had also established a metropolis–a planned urban center housing tens of thousands. Located on the American Bottom, where the Missouri, the Illinois, and the Kankakee rivers flow into the Mississippi, the Indian city we call Cahokia culturally dominated a densely populated region from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Rockies to the Appalachians. Cahokia was based on corn agriculture, a compelling belief system, and a trading network that spanned half the continent.

Cahokia is unique in North America because of its geographic reach, the skills of its builders and astronomers, and the sophistication of its culture. Cahokia is one of the few places in the world where a complex level of social organization evolved without the impetus of outside conquest or diffusion. Strangely, the Toltecs of Mexico, the Anasazi of the American Southwest, and Cahokia have almost identical trajectories. All rose and fell at the same time but only the Toltecs were preceded by another complex civilization. Because the Anasazi left buildings of stone their culture may appear to have been more sophisticated than that of Cahokia. It was not. The Cahokia phenomenon was much greater.

Cahokia dominated the heart of North America for approximately four hundred years–from ad 900 to 1300. Yet the city had been abandoned for two centuries when the first Europeans arrived. Settlers saw only hundreds of mounds, some—despite centuries of erosion—still as high as ten-story buildings. They found it hard to believe these massive structures could have been built by the despised Indians and so theorized they had been constructed by someone else—the Spaniards, perhaps, or the Vikings or descendants of Canaanite refugees from Palestine!

Not until the second half of the twentieth century did archaeologists grasp the full extent of Cahokia—a Native American metropolis larger than any other city in North America until Philadelphia eclipsed it in 1800, a city whose downtown covered six and a half square miles with suburbs extending another fifteen miles in all directions, a city that was a destination for worshipping pilgrims.

While Cahokia was flourishing in North America, London and Paris were still villages, Ethelred II was bribing the Danes to cease their raids on England, Leif Eriksson was finding his way to Newfoundland, and the Visigoths and Moors were battling for control of Spain.

If I could visit Cahokia, I would choose to be present on the day in approximately 1030 when a great chief, his retainers, and his servants were buried at the site modern–day archaeologists have labeled Mound 72.

***

The air is humid, so saturated that the first rays of the sun cast a defused light over the landscape. I am standing on the bank of a river that drains over half the continent and for a moment the backlit rising mist gives the appearance that water and sky are one. Here, at its midpoint, the river flows steadily south through a mile-wide maze of islands, sloughs, eddies, and backwaters.

The stillness that greeted the rising of the sun is broken by the calls of hundreds of birds taking flight from the marshes. Turtles slip off floating logs into the water, fish break the surface to strike at hovering insects, and muskrats drop with distant splashes into the river. Though the sun has barely risen above the horizon, its heat is already oppressive.

To my left is the valley of the great river and to my right, in the far distance, is the escarpment of the vast eastern prairie. Between them lies a flat crescent of land, ten miles wide at its widest point and eighty miles long from north to south. This fertile bottomland is the cradle of Cahokia.

Other sounds now come from the river—the rhythmic strokes of canoe paddles, dipping and pulling through the water in measured cadences. Emerging through the mist, ghostlike, a fleet of a dozen high–prowed canoes, each carrying forty or more individuals, appears. The canoes move swiftly upriver toward the mouth of a smaller stream that empties into the river near where I am standing. Each canoe in the line makes the right turn into the smaller stream, heading northeast, and soon they have passed me by and are out of sight.

I am not alone. My companion is a youth, Anton, who is acting as my guide. We are among a throng of hundreds who, though it is still early in the morning, are striding purposefully toward Cahokia along this wide road topping the ridge bordering the stream. I had stepped aside to watch the passage of the canoes and to survey the landscape, but now I rejoin the crowd, jogging to catch up with Anton and his companions.

A short distance from where the stream empties into the river we come to some of the most dramatic features of the landscape— enormous mounds, rising like giant breasts on the flat land. The first group is a cluster of forty-five arranged in a semicircle over a mile in diameter. Anton laughs at my frustration as I try to estimate the size of the mounds—each one several hundred feet around its base, many bearing buildings on their summits. The tops of some of the mounds have been flattened into what look to be parade grounds so large that, if so ordered, hundreds of men could execute maneuvers on them.

Cahokia, Anton explains, has men who are mathematicians, engineers, and materials specialists whose task it is to design and supervise all construction. Once a mound is designed and its location approved by the priests, everyone participates in its building, carrying basket load after basket load of soil to the site. Anton points to one of the mounds and tells me his relatives helped build it.

There is tension in the air and Anton makes no attempt to hide his excitement. Drums have been beating for many days, he tells me, hunters have brought food for thousands to the city, and enormous storage pits of grains have been opened in preparation for the ceremonies that will soon take place. A powerful chief has died and today he will be buried. The leaders of Indian communities for hundreds of miles up and down the river, along with their retainers and nobles, have come to Cahokia to participate.

Some will have brought tribute to be interred with the fallen leader—a politically significant acknowledgment of Cahokia’s dominance over the region.

The men around me wear brightly colored tunics of woven cloth and the women short skirts wrapped around their waists. Many of the garments are ornamented with pink and white shell beads so finely crafted that it takes twenty-four hundred beads to fill a quart measure. All wear leather foot gear and most carry packs of provisions on their backs. Many of the men also carry spears, bundles of bows and arrows, and deerskin pouches filled with arrow points. A few wear long capes embroidered with thousands of beads and these individuals are treated with respect, bordering on reverence, by others.

Around us the bottomland is planted in corn mingled with varieties of tomatoes, beans, squash, and peppers, the vines of the beans twisting around the cornstalks in an exuberant embrace. Punctuating the fields are occasional houses, the walls made of sticks sunk into the ground and plastered with mud and straw. The steeply pitched roofs are covered with mats of thatch. Paths, like long stems, connect the houses to the road on which hundreds of us are now walking.

As we pass one field Anton steps to the side and picks two tomatoes. Plucking off the stem, he hands one to me with a grin and sinks his teeth into the other. I take a bite and we stride on, juice dripping off our wrists.

***

Canoe landing areas, broad leveled sections of stream bank, appear frequently. Just ahead of me a line of laden canoes pulls up at the bank. People of all ages disembark, hand up bundles of cargo, and then stand together in groups, waiting until everyone is ashore before continuing the journey. The high pitch of their voices betrays their anticipation. At a signal from a leader, they move off.

We come upon more mounds, spaced at regular intervals, fires blazing on their summits, that form a ceremonial entrance to the city. I turn off the road onto a path leading to the summit of a mound to get a better view and there, lying before me for as far as I can see, are the tightly packed residences of Cahokia, the Indian metropolis. Its suburbs extend for leagues beyond in every direction.

We pass another enormous mound. I interrupt our progress to pace it off and find it measures more than three hundred feet long, its height at least fifty feet. Anton tells me ancestors of Cahokia are buried near its summit. We are now part of a river of people that flows around the base of the mound like water around an island in a stream.

We have entered the city from the east and are in a neighborhood where the houses are lined up, side by side, with only a few feet between each residence. At each house women are cooking food over a fire. I sniff appreciatively as smoke from a thousand cooking fires rises in the still morning air bearing the fragrance of roasting meat.

Children race about, adults call to one another, penned-up turkeys gobble, and in the background is the ever–present sound of drumming and the haunting tones of notes blown through instruments made from seashells.

***

Walking due west we emerge from the confines of the neighborhood and come to a circle of forty-eight massive posts, each one about thirty feet high and set deep into the ground. The posts are arranged in a perfect circle over four hundred feet in diameter. Anton approaches the circle with solemnity and makes some gestures that I interpret as signs of reverence. The area inside is covered with a layer of fine white sand and I am struck by the fact that, except for the tracks made by birds or a running animal, the sand is undisturbed. No one, not even an errant child, walks inside the circle of posts. This is sacred space.

Anton has more to tell me. If I had a high place on which to stand so that I could look across the expanse of downtown Cahokia, he says, I would see that there are four of these giant place-marking sacred circles, one at each of the cardinal points of the compass–North, South, East, and West. The mound that I can see ahead of us in the distance rises at the point where lines from the four circles cross. This, one of the largest earthen constructions in the Western Hemisphere, is the Great Mound on which stands the residence of the Lord of Cahokia.

The log circles, Anton explains, reflect the plan of the city. The people of Cahokia envision their cosmos as a great circle with an east-west axis representing the pathway of the sun. We are at the circle representing the East. The North, believed to be Sky World, is represented by a circle monument far to my right, across the stream and near another cluster of mounds and houses. The South is Earth World, where many of today’s ceremonies will take place, adjacent to the consecrated ground of the south circle. Cahokia is laid out as a mirror of the cosmos.

Careful to walk around and not across the sacred circle, we approach the central precinct of downtown Cahokia encircled by a massive log palisade. Inside the palisade is the Great Mound, the Grand Plaza, and the residences of the elite of Cahokia. The log palisade, plastered inside and out, stands thirty feet high with bastions located at regular intervals. I gape at it in astonishment. At least twenty thousand logs had to have gone into the construction of this palisade, most of them measuring almost three feet in diameter. “How did they ever cut these logs?” I ask Anton. In reply he pulls his hatchet from his bag. It is edged with sharp black obsidian, the volcanic glass from the Rocky Mountains.

Guards standing on platforms within the bastions scrutinize us as we approach. After an initial hesitation they recognize Anton and wave us through. We step out onto the Grand Plaza of Cahokia. Before us is a 200-acre expanse, five times the size of St. Peter’s Square in Rome, that has been reclaimed from the ridge and swale topography of the river bottomland and raised three feet to create this giant, perfectly flat ceremonial space. I am staggered at the labor involved in constructing it. I give Anton a questioning look and he pantomimes dumping a basket of soil on the ground.

On my right, at the north side of the plaza, standing more than a hundred feet high and broader at its base than the great pyramid of Egypt, is the Great Mound of Cahokia. It covers sixteen acres, contains twenty-two million cubic feet of earth, and rises through four terraces to its summit, where the Lord of Cahokia lives in his grand residence. A broad stairway leads from the plaza to the top of the mound.

Seventeen additional mounds are enclosed within the walls of the palisade. Fifteen mounds are arranged in rows along the east and west sides of the plaza, while twin mounds guard the southern end. Some mounds have buildings on their summits, others blaze with fires that are never extinguished.

The sun is high in the sky and, despite my midmorning snack of tomatoes, I am growing hungry. Anton invites me into his home within the palisade to eat. His residence consists of a complex of five buildings surrounding a courtyard where a tall post, painted in colors, flies a standard. When I step down into one of the houses—the floor is almost eight inches below the level of the courtyard—and leave the brilliant noonday sun it takes my eyes a minute to adjust to the dim light. I am in a rectangular room measuring about thirty square yards and covered with a high thatch roof. This building, like all the other buildings in Cahokia, is oriented to the cardinal directions with the long axis running east to west.

The floor is hard-packed dirt covered with woven mats; the walls, benches, interior screens, and stools are of wood–hickory, oak, red cedar, bald ypress, and cottonwood. Although there is a cooking hearth inside, the cook, perhaps because the day is hot, is working under a cooking shelter outside. Venison is frying in a shallow ceramic skillet over a charcoal fire, and dried corn, mixed with squash and peppers, is simmering in a pot. The aroma wafts to where I am resting on a bench in the cool shade inside. From time to time the cook comes into the house to get ingredients from an assortment of ceramic storage jars semiburied in the floor of the house.

I am impressed by the size of the containers. While the cook is out I examine her storage facilities and discover one massive ceramic pot with a capacity of at least 110 liters. On a shelf are dozens of ceramic bowls of different sizes with incised designs. In a corner are limestone and sandstone slabs of rock used for grinding seeds into meal and an assortment of hoes, made with mussel shells tied onto wood shafts. Skins of bear and other furs lie in a heap in a corner.

When the woman calls me to eat I go outside to join Anton and other members of his family in the courtyard, where I am offered a piece of meat from the haunch of a white-tailed deer, some boiled bones with the flesh of birds attached, and a clay bowl of soup. The meat is tender and Anton explains that his family is brought only the best parts of the deer. The implication is clear. Those living within the palisade are the aristocrats of Cahokia, maintained in their position by a complex hierarchical system. Anton’s family does not hunt for its own meat. Because of his parents’ status, only the choicest game is brought to them.

We have finished eating and are chewing at the bones, when my male companions suddenly tense and get to their feet. The tempo of the drumming has changed. Anton pulls me to my feet, telling me we must join the throngs now streaming through the gates of the palisade to stand in expectant ranks facing the Great Mound. Soon the entire plaza is filled with men, women, and children, shifting from foot to foot, eyes fixed on the summit of the pyramid.

For a long time nothing happens. Then a hush falls over the crowd as a dozen men wearing long capes and carrying spears step to the edge of the upper terrace. They descend a few steps and pause. Behind them, in the center of the mound, a man suddenly appears. He is wearing a tall feathered headdress, a copper plate on his chest, and a long beaded cape that falls to his feet. The shells on his cape glisten in the sun and his polished breast plate reflects the rays like a mirror. For a moment the man stands alone at the top of the mound, the sun shining directly down on him. Then he raises his bracelet-lined arms over his head. The crowd gasps, then roars its approval as the Lord of Cahokia acknowledges the greeting and begins his slow descent to the plaza.

The twelve warriors who preceded the chief down the steps are joined by thirty more who form a phalanx to escort the chief and his attendants to the ceremonies. Accompanying them are musicians blowing on shell horns, drummers, and dancers shaking rattles. Other officials appear from the crowd wearing beaded emblems of their office, expertly clearing the way for the chief.

Their task is not difficult. The crowd parts and falls back as the officials approach. Those closest make signs of reverence. Only after the officials are well past does the throng fall in behind to walk the length of the Grand Plaza, pass between the twin mounds at the southern end and through the bastions in the palisade wall, to gather near the circle of logs representing the Earth World. Anton grabs my arm, tugs me through the crowd, and places me, with him, in the front rank of the spectators.

The Lord of Cahokia takes his position within the sacred circle. When he is seated, surrounded by his courtiers, attention shifts to the large shallow pit that has been dug just inside the circle of logs. The warriors clear a path as a procession of litter bearers come out of a nearby charnel house bearing the body of a young man that is placed, facedown, in the pit. When the body is in position, other officials appear carrying a robe, almost six feet long, embroidered with twenty thousand shell beads to form the shape of a falcon. The work is so fine I can see the wings and tail feathers delineated in the beadwork. A murmur of admiration goes up from the crowd when the robe is held up for all to see.

Four men step into the shallow pit and carefully spread the falcon robe over the body of the young man. The crowd falls silent with expectation. Then drumming begins and bearers appear carrying the body of a man dressed in long robes. At sight of the body the crowd begins to moan and cry out in a ritual display of grief. To the beating of drums the litter bearers slowly approach the grave. Men wearing ceremonial capes lower the body onto the beaded falcon robe and carefully arrange the limbs, arms down to the sides, the head just below and to the left of the falcon’s, the feet touching the tail feathers.

As the wailing continues, bundles of human bones are brought from the charnel house to place in the grave. Some bundles contain only leg bones, others have the bones of ribs or of arms. These, Anton whispers to me, are the bones of the chief’s ancestors and relatives, picked clean of flesh and kept until the time when they can be interred as part of this prestigious burial.

Now a more ominous sight appears. Three men and three women, all in their middle years, are led up to the grave. They were servants of the chief, Anton whispers again, and they must now follow him in death. The six do not resist and appear, if not to welcome, to accept their fate. While a few individuals in the crowd of observers wail and beat their chests, a man with a strong cord wrapped around his hands steps behind each victim, swiftly loops the cord around the neck, and chokes each one to death. As they die their bodies are lifted into the grave and placed beside that of their master.

Once the six have been killed, the tempo changes. A parade of rulers, some of whom have come long distances to pay tribute to the dead chief step forward. One bears a three-foot-long sheet of rolled-up beaten copper that could only have come from the region around Lake Superior. With great ceremony he places it in the grave. Another chief steps up and, at his nod, bearers bring forth baskets of precious mica–totaling several bushels full—that came from near the Atlantic Ocean. This too goes into the grave.

Chiefs and subchiefs come forward carrying bundles of arrows tipped with stone points as finely crafted as jewelry. Some of the arrow points are of black chert from Arkansas and Oklahoma, others are of kaolin chert from southern Illinois, while still more are of stone from Tennessee and Wisconsin. I try to count the number of new shafted arrows that go into the grave and give up when the number reaches over a thousand.

The last objects placed in the grave are fifteen polished double-concave stone discs made of granite. Five inches in diameter, the rare stones are used in sporting events. These discs are among the most prized possessions of ruling chiefs and their tribes. This gift is a near unbelievable gesture of fealty to Cahokia’s gods. I glance at Anton for an explanation but he is staring at the discs as if mesmerized.

I realize that I am watching a fortune, a king’s ransom, being buried with this chief. Only the most powerful of leaders can command such a conspicuous consumption of grave goods. I think the event is over, but it is not. Again the mood changes. The murmuring has stopped and the crowd has fallen silent. I note that the bodies of the chief, those of the six murdered retainers, and the elaborate gifts do not begin to fill the excavated space and I wonder what other kind of tribute will be offered to demonstrate submission to the power of Cahokia and cement alliances with its powerful lord.

I do not have long to wait. The drumming resumes. A few cry out. There is a brief struggle and then two men appear from the crowd holding a young woman between them. She is made to stand at the edge of the pit while more young women are brought to stand beside her. When ten have been gathered, they are turned to face the grave. Then the man with the garrote goes down the line, quickly strangling each in turn. They struggle very little, as if resigned to their fate. As they die, their bodies are laid carefully in the grave, each one placed neatly next to her sister victim.

No sooner are the ten strangled and placed in the grave than ten more are lined up, and then ten more. The garroting does not stop until fifty young women, all between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three, have been killed. There is not enough room to line them all up in the grave so the bodies are stacked carefully on top of one another in layers. I am told that none of the young women are from Cahokia. All are tribute paid to the city by a distant chief.

The sun is near to setting when the last bodies are brought out of the charnel house. Four male corpses are lowered into the grave and positioned, side by side, with their arms overlapping in a comradely fashion. The puzzling aspect of their burial is that all four are missing their heads and hands.

As the sun sets and the air turns cooler, I sit alone by the river and ponder the meaning of what I have seen. The chief buried on the robe of beads in the shape of a falcon may represent the Sky World because raptors are powerful symbols of the sky. The man buried beneath him, facedown, may symbolize the Earth World. Can the four headless men represent the four directions, a number universally significant to the Indians of North America?

I wonder if the conspicuous display of gifts placed in the grave was competition among chieftains for the favor of the Lord of Cahokia. But who won the competition and what of the ritual deaths? Impressive as were the tributes of copper, mica, polished stones, and arrows, how can they compare with the gift of human lives? I pitch a stone into the black water and hope the young women believed themselves honored to have been selected to accompany the great chief on his journey to another life.

Both political and religious power, I decide, rules Cahokia– power that profoundly influences, if not controls, life over the region marked by the Mississippi River and its many tributaries. Some of Cahokia’s power comes from the fact that it is the first large population center to exist in North America. Its size alone, coupled with its trading network, impacts regions far beyond its apparent domain.

On this day in the year 1030 of the Common Era, Cahokia reigns as North America’s Rome, the locus of skilled agronomists, astronomer priests, engineers of enormous earthworks and stockades–the destination of awestruck worshippers who travel for hundreds of miles to see the sacred fires burning on the hilltops of the gods.

***

Mary Beth Norton

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

Mary Beth Norton, the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of American History at Cornell University, has written a number of books in early American history. Among them are The British-Americans; Liberty’s Daughters; Founding Mothers and Fathers, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; and In the Devil’s Snare, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in history and winner of the Ambassador Book Award in American Studies. Professor Norton is an elected fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In this essay Mary Beth Norton takes herself, and the reader, back to the Salem witch trials. In telling her story she dispels some myths and she tries to discover a few things that go beyond the existing historical evidence.

***

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

While I was researching and writing In the Devil’s Snare, my book on the Salem witch trials of 1692, I became utterly obsessed with witchcraft. Others have had analogous experiences, as John Demos, for example, reports in the preface of his 1982 book, Entertaining Satan. Some nights, I was so overwhelmed by the material I was reading that I tossed and turned sleeplessly for hours. For several years, every conversation I had with another historian seemed to end up being about witchcraft. During January through June of one year, I also thought it perfectly logical to compose a different message for my telephone answering machine each week, briefly explaining what had happened in Essex County, Massachusetts, on the same dates in 1692.

Only in retrospect have I realized how fully “bewitched” by my topic I was and come to understand that my friends had a point when they remarked that they found my ever-changing historical outgoing messages strange. (Other friends, though, fed my obsession by calling the house when they knew I’d be out, to obtain their weekly update on the latest news from 1692 Salem.)

Thus, not surprisingly, the historical event I would most like to have observed in person is the witchcraft crisis, especially the months between mid-January and late October 1692. Living through those months would surely have been emotionally draining, but such an experience would have answered many questions for modern scholars. Despite the hundreds of pages of surviving documents and many books by dedicated researchers, there is still much we don’t know about those days–and will probably never know, absent major new documentary discoveries.

***

To most Americans, the Salem witch trials serve today as a negative reference point–an example of hysterical fear blown out of all proportion to reality. In our collective consciousness, the trials have primarily become something to avoid replicating. Thus critics of, for instance, the impeachment of Bill Clinton or the 1980s charges against day-care providers for child sexual abuse have likened those prosecutions to witch hunts and specifically to the Salem trials. Arthur Miller’s well-known 1953 play, The Crucible, now frequently assigned in high school literature courses, inextricably linked the 1692 trials to the spate of anti-Communist hearings conducted in the early 1950s by the House Un-American Activities Committee and senators like Joseph McCarthy.

The seemingly modern relevance of the trials, coupled with past studies including ax grinding of a particular sort, have created a number of mistaken impressions of the trials in Americans’ minds. Scenes wholly from Miller’s imagination, for example, inform many Americans’ views of the events of 1692. Although such moments are vividly depicted in The Crucible, neither naked girls dancing in the woods while practicing voodoo nor an adulterous affair between Miller’s hero, John Proctor, and the Reverend Parris’s niece, Abigail Williams, appear anywhere in the surviving records. There is also no evidence that the witchcraft accusations represented an attempt by some people to steal other people’s land. Some descendants of convicted witches have contended that their ancestors were victimized by conspiracies of vengeful neighbors seeking to line their own pockets. Judging by questions I often receive after my lectures, one false notion is widely held: the belief that successful accusers of witches were rewarded by being given their victims’ landed estates. True, colonial officials could—but did not always—confiscate the personal property of executed witches, but any proceeds were to go to the crown, not to accusers. (In 1692, a greedy sheriff seized some personal property, but it is not clear what he did with it, nor was he involved in the initial accusations.) Lands and houses were not confiscated but instead descended to the heirs of those executed. Moreover, since many of the people hanged in 1692 were married women, they could not own property under coverture laws—when a woman married, all

her property passed to her husband. Thus an executed wife had no property that could have been turned over to anyone else, and in only one family were both husband and wife executed.

To understand the witchcraft crisis and what I would have gained by witnessing it, therefore, the first focus should be to recover what happened in 1692, ignoring the overlays of subsequent interpretations.(*)

From the Hardcover edition.

A Day in Cahokia–AD 1030

Biloine (Billie) Young lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and is involved there in a number of cultural and civic activities. She is also the founder of Centro Colombo Americano, an educational and cultural center in Cali, Colombia. Among her published books are Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis; Mexican Odyssey: Our Search for the People’s Art; A Dream for Gilberto: An Immigrant Family’s Struggle to Become American; and Three Hundred Years on the Upper Mississippi. In this essay Billie Young takes an imaginary journey to the Mississippi River metropolis of Cahokia in the summer of 1030. It is an unforgettable experience.

***

A Day in Cahokia–AD 1030

One of the first discoveries made by the Spanish who came to the New World following Columbus was that the Americas were filled with people living in advanced civilizations. Cortez and his men were astounded, in 1519, at the sight of the Aztec Tenochtitlán, a city of 300,000 that was larger, cleaner, and more efficiently managed than any in Europe. The sight was so extraordinary that the superstitious soldiers thought they had been enchanted “on account of the great towers and pyramids and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry.” Houses, shaded with cotton awnings, were “well made of cut stone, cedar, and other fragrant woods, with great rooms and patios, all plastered and bright.”

The Europeans would have been even more amazed if they had known that five hundred years earlier the Indians of North America had also established a metropolis–a planned urban center housing tens of thousands. Located on the American Bottom, where the Missouri, the Illinois, and the Kankakee rivers flow into the Mississippi, the Indian city we call Cahokia culturally dominated a densely populated region from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Rockies to the Appalachians. Cahokia was based on corn agriculture, a compelling belief system, and a trading network that spanned half the continent.

Cahokia is unique in North America because of its geographic reach, the skills of its builders and astronomers, and the sophistication of its culture. Cahokia is one of the few places in the world where a complex level of social organization evolved without the impetus of outside conquest or diffusion. Strangely, the Toltecs of Mexico, the Anasazi of the American Southwest, and Cahokia have almost identical trajectories. All rose and fell at the same time but only the Toltecs were preceded by another complex civilization. Because the Anasazi left buildings of stone their culture may appear to have been more sophisticated than that of Cahokia. It was not. The Cahokia phenomenon was much greater.

Cahokia dominated the heart of North America for approximately four hundred years–from ad 900 to 1300. Yet the city had been abandoned for two centuries when the first Europeans arrived. Settlers saw only hundreds of mounds, some—despite centuries of erosion—still as high as ten-story buildings. They found it hard to believe these massive structures could have been built by the despised Indians and so theorized they had been constructed by someone else—the Spaniards, perhaps, or the Vikings or descendants of Canaanite refugees from Palestine!

Not until the second half of the twentieth century did archaeologists grasp the full extent of Cahokia—a Native American metropolis larger than any other city in North America until Philadelphia eclipsed it in 1800, a city whose downtown covered six and a half square miles with suburbs extending another fifteen miles in all directions, a city that was a destination for worshipping pilgrims.

While Cahokia was flourishing in North America, London and Paris were still villages, Ethelred II was bribing the Danes to cease their raids on England, Leif Eriksson was finding his way to Newfoundland, and the Visigoths and Moors were battling for control of Spain.

If I could visit Cahokia, I would choose to be present on the day in approximately 1030 when a great chief, his retainers, and his servants were buried at the site modern–day archaeologists have labeled Mound 72.

***

The air is humid, so saturated that the first rays of the sun cast a defused light over the landscape. I am standing on the bank of a river that drains over half the continent and for a moment the backlit rising mist gives the appearance that water and sky are one. Here, at its midpoint, the river flows steadily south through a mile-wide maze of islands, sloughs, eddies, and backwaters.

The stillness that greeted the rising of the sun is broken by the calls of hundreds of birds taking flight from the marshes. Turtles slip off floating logs into the water, fish break the surface to strike at hovering insects, and muskrats drop with distant splashes into the river. Though the sun has barely risen above the horizon, its heat is already oppressive.

To my left is the valley of the great river and to my right, in the far distance, is the escarpment of the vast eastern prairie. Between them lies a flat crescent of land, ten miles wide at its widest point and eighty miles long from north to south. This fertile bottomland is the cradle of Cahokia.

Other sounds now come from the river—the rhythmic strokes of canoe paddles, dipping and pulling through the water in measured cadences. Emerging through the mist, ghostlike, a fleet of a dozen high–prowed canoes, each carrying forty or more individuals, appears. The canoes move swiftly upriver toward the mouth of a smaller stream that empties into the river near where I am standing. Each canoe in the line makes the right turn into the smaller stream, heading northeast, and soon they have passed me by and are out of sight.

I am not alone. My companion is a youth, Anton, who is acting as my guide. We are among a throng of hundreds who, though it is still early in the morning, are striding purposefully toward Cahokia along this wide road topping the ridge bordering the stream. I had stepped aside to watch the passage of the canoes and to survey the landscape, but now I rejoin the crowd, jogging to catch up with Anton and his companions.

A short distance from where the stream empties into the river we come to some of the most dramatic features of the landscape— enormous mounds, rising like giant breasts on the flat land. The first group is a cluster of forty-five arranged in a semicircle over a mile in diameter. Anton laughs at my frustration as I try to estimate the size of the mounds—each one several hundred feet around its base, many bearing buildings on their summits. The tops of some of the mounds have been flattened into what look to be parade grounds so large that, if so ordered, hundreds of men could execute maneuvers on them.

Cahokia, Anton explains, has men who are mathematicians, engineers, and materials specialists whose task it is to design and supervise all construction. Once a mound is designed and its location approved by the priests, everyone participates in its building, carrying basket load after basket load of soil to the site. Anton points to one of the mounds and tells me his relatives helped build it.

There is tension in the air and Anton makes no attempt to hide his excitement. Drums have been beating for many days, he tells me, hunters have brought food for thousands to the city, and enormous storage pits of grains have been opened in preparation for the ceremonies that will soon take place. A powerful chief has died and today he will be buried. The leaders of Indian communities for hundreds of miles up and down the river, along with their retainers and nobles, have come to Cahokia to participate.

Some will have brought tribute to be interred with the fallen leader—a politically significant acknowledgment of Cahokia’s dominance over the region.

The men around me wear brightly colored tunics of woven cloth and the women short skirts wrapped around their waists. Many of the garments are ornamented with pink and white shell beads so finely crafted that it takes twenty-four hundred beads to fill a quart measure. All wear leather foot gear and most carry packs of provisions on their backs. Many of the men also carry spears, bundles of bows and arrows, and deerskin pouches filled with arrow points. A few wear long capes embroidered with thousands of beads and these individuals are treated with respect, bordering on reverence, by others.

Around us the bottomland is planted in corn mingled with varieties of tomatoes, beans, squash, and peppers, the vines of the beans twisting around the cornstalks in an exuberant embrace. Punctuating the fields are occasional houses, the walls made of sticks sunk into the ground and plastered with mud and straw. The steeply pitched roofs are covered with mats of thatch. Paths, like long stems, connect the houses to the road on which hundreds of us are now walking.

As we pass one field Anton steps to the side and picks two tomatoes. Plucking off the stem, he hands one to me with a grin and sinks his teeth into the other. I take a bite and we stride on, juice dripping off our wrists.

***

Canoe landing areas, broad leveled sections of stream bank, appear frequently. Just ahead of me a line of laden canoes pulls up at the bank. People of all ages disembark, hand up bundles of cargo, and then stand together in groups, waiting until everyone is ashore before continuing the journey. The high pitch of their voices betrays their anticipation. At a signal from a leader, they move off.

We come upon more mounds, spaced at regular intervals, fires blazing on their summits, that form a ceremonial entrance to the city. I turn off the road onto a path leading to the summit of a mound to get a better view and there, lying before me for as far as I can see, are the tightly packed residences of Cahokia, the Indian metropolis. Its suburbs extend for leagues beyond in every direction.

We pass another enormous mound. I interrupt our progress to pace it off and find it measures more than three hundred feet long, its height at least fifty feet. Anton tells me ancestors of Cahokia are buried near its summit. We are now part of a river of people that flows around the base of the mound like water around an island in a stream.

We have entered the city from the east and are in a neighborhood where the houses are lined up, side by side, with only a few feet between each residence. At each house women are cooking food over a fire. I sniff appreciatively as smoke from a thousand cooking fires rises in the still morning air bearing the fragrance of roasting meat.

Children race about, adults call to one another, penned-up turkeys gobble, and in the background is the ever–present sound of drumming and the haunting tones of notes blown through instruments made from seashells.

***

Walking due west we emerge from the confines of the neighborhood and come to a circle of forty-eight massive posts, each one about thirty feet high and set deep into the ground. The posts are arranged in a perfect circle over four hundred feet in diameter. Anton approaches the circle with solemnity and makes some gestures that I interpret as signs of reverence. The area inside is covered with a layer of fine white sand and I am struck by the fact that, except for the tracks made by birds or a running animal, the sand is undisturbed. No one, not even an errant child, walks inside the circle of posts. This is sacred space.

Anton has more to tell me. If I had a high place on which to stand so that I could look across the expanse of downtown Cahokia, he says, I would see that there are four of these giant place-marking sacred circles, one at each of the cardinal points of the compass–North, South, East, and West. The mound that I can see ahead of us in the distance rises at the point where lines from the four circles cross. This, one of the largest earthen constructions in the Western Hemisphere, is the Great Mound on which stands the residence of the Lord of Cahokia.

The log circles, Anton explains, reflect the plan of the city. The people of Cahokia envision their cosmos as a great circle with an east-west axis representing the pathway of the sun. We are at the circle representing the East. The North, believed to be Sky World, is represented by a circle monument far to my right, across the stream and near another cluster of mounds and houses. The South is Earth World, where many of today’s ceremonies will take place, adjacent to the consecrated ground of the south circle. Cahokia is laid out as a mirror of the cosmos.

Careful to walk around and not across the sacred circle, we approach the central precinct of downtown Cahokia encircled by a massive log palisade. Inside the palisade is the Great Mound, the Grand Plaza, and the residences of the elite of Cahokia. The log palisade, plastered inside and out, stands thirty feet high with bastions located at regular intervals. I gape at it in astonishment. At least twenty thousand logs had to have gone into the construction of this palisade, most of them measuring almost three feet in diameter. “How did they ever cut these logs?” I ask Anton. In reply he pulls his hatchet from his bag. It is edged with sharp black obsidian, the volcanic glass from the Rocky Mountains.

Guards standing on platforms within the bastions scrutinize us as we approach. After an initial hesitation they recognize Anton and wave us through. We step out onto the Grand Plaza of Cahokia. Before us is a 200-acre expanse, five times the size of St. Peter’s Square in Rome, that has been reclaimed from the ridge and swale topography of the river bottomland and raised three feet to create this giant, perfectly flat ceremonial space. I am staggered at the labor involved in constructing it. I give Anton a questioning look and he pantomimes dumping a basket of soil on the ground.

On my right, at the north side of the plaza, standing more than a hundred feet high and broader at its base than the great pyramid of Egypt, is the Great Mound of Cahokia. It covers sixteen acres, contains twenty-two million cubic feet of earth, and rises through four terraces to its summit, where the Lord of Cahokia lives in his grand residence. A broad stairway leads from the plaza to the top of the mound.

Seventeen additional mounds are enclosed within the walls of the palisade. Fifteen mounds are arranged in rows along the east and west sides of the plaza, while twin mounds guard the southern end. Some mounds have buildings on their summits, others blaze with fires that are never extinguished.

The sun is high in the sky and, despite my midmorning snack of tomatoes, I am growing hungry. Anton invites me into his home within the palisade to eat. His residence consists of a complex of five buildings surrounding a courtyard where a tall post, painted in colors, flies a standard. When I step down into one of the houses—the floor is almost eight inches below the level of the courtyard—and leave the brilliant noonday sun it takes my eyes a minute to adjust to the dim light. I am in a rectangular room measuring about thirty square yards and covered with a high thatch roof. This building, like all the other buildings in Cahokia, is oriented to the cardinal directions with the long axis running east to west.

The floor is hard-packed dirt covered with woven mats; the walls, benches, interior screens, and stools are of wood–hickory, oak, red cedar, bald ypress, and cottonwood. Although there is a cooking hearth inside, the cook, perhaps because the day is hot, is working under a cooking shelter outside. Venison is frying in a shallow ceramic skillet over a charcoal fire, and dried corn, mixed with squash and peppers, is simmering in a pot. The aroma wafts to where I am resting on a bench in the cool shade inside. From time to time the cook comes into the house to get ingredients from an assortment of ceramic storage jars semiburied in the floor of the house.

I am impressed by the size of the containers. While the cook is out I examine her storage facilities and discover one massive ceramic pot with a capacity of at least 110 liters. On a shelf are dozens of ceramic bowls of different sizes with incised designs. In a corner are limestone and sandstone slabs of rock used for grinding seeds into meal and an assortment of hoes, made with mussel shells tied onto wood shafts. Skins of bear and other furs lie in a heap in a corner.

When the woman calls me to eat I go outside to join Anton and other members of his family in the courtyard, where I am offered a piece of meat from the haunch of a white-tailed deer, some boiled bones with the flesh of birds attached, and a clay bowl of soup. The meat is tender and Anton explains that his family is brought only the best parts of the deer. The implication is clear. Those living within the palisade are the aristocrats of Cahokia, maintained in their position by a complex hierarchical system. Anton’s family does not hunt for its own meat. Because of his parents’ status, only the choicest game is brought to them.

We have finished eating and are chewing at the bones, when my male companions suddenly tense and get to their feet. The tempo of the drumming has changed. Anton pulls me to my feet, telling me we must join the throngs now streaming through the gates of the palisade to stand in expectant ranks facing the Great Mound. Soon the entire plaza is filled with men, women, and children, shifting from foot to foot, eyes fixed on the summit of the pyramid.

For a long time nothing happens. Then a hush falls over the crowd as a dozen men wearing long capes and carrying spears step to the edge of the upper terrace. They descend a few steps and pause. Behind them, in the center of the mound, a man suddenly appears. He is wearing a tall feathered headdress, a copper plate on his chest, and a long beaded cape that falls to his feet. The shells on his cape glisten in the sun and his polished breast plate reflects the rays like a mirror. For a moment the man stands alone at the top of the mound, the sun shining directly down on him. Then he raises his bracelet-lined arms over his head. The crowd gasps, then roars its approval as the Lord of Cahokia acknowledges the greeting and begins his slow descent to the plaza.

The twelve warriors who preceded the chief down the steps are joined by thirty more who form a phalanx to escort the chief and his attendants to the ceremonies. Accompanying them are musicians blowing on shell horns, drummers, and dancers shaking rattles. Other officials appear from the crowd wearing beaded emblems of their office, expertly clearing the way for the chief.

Their task is not difficult. The crowd parts and falls back as the officials approach. Those closest make signs of reverence. Only after the officials are well past does the throng fall in behind to walk the length of the Grand Plaza, pass between the twin mounds at the southern end and through the bastions in the palisade wall, to gather near the circle of logs representing the Earth World. Anton grabs my arm, tugs me through the crowd, and places me, with him, in the front rank of the spectators.

The Lord of Cahokia takes his position within the sacred circle. When he is seated, surrounded by his courtiers, attention shifts to the large shallow pit that has been dug just inside the circle of logs. The warriors clear a path as a procession of litter bearers come out of a nearby charnel house bearing the body of a young man that is placed, facedown, in the pit. When the body is in position, other officials appear carrying a robe, almost six feet long, embroidered with twenty thousand shell beads to form the shape of a falcon. The work is so fine I can see the wings and tail feathers delineated in the beadwork. A murmur of admiration goes up from the crowd when the robe is held up for all to see.

Four men step into the shallow pit and carefully spread the falcon robe over the body of the young man. The crowd falls silent with expectation. Then drumming begins and bearers appear carrying the body of a man dressed in long robes. At sight of the body the crowd begins to moan and cry out in a ritual display of grief. To the beating of drums the litter bearers slowly approach the grave. Men wearing ceremonial capes lower the body onto the beaded falcon robe and carefully arrange the limbs, arms down to the sides, the head just below and to the left of the falcon’s, the feet touching the tail feathers.

As the wailing continues, bundles of human bones are brought from the charnel house to place in the grave. Some bundles contain only leg bones, others have the bones of ribs or of arms. These, Anton whispers to me, are the bones of the chief’s ancestors and relatives, picked clean of flesh and kept until the time when they can be interred as part of this prestigious burial.

Now a more ominous sight appears. Three men and three women, all in their middle years, are led up to the grave. They were servants of the chief, Anton whispers again, and they must now follow him in death. The six do not resist and appear, if not to welcome, to accept their fate. While a few individuals in the crowd of observers wail and beat their chests, a man with a strong cord wrapped around his hands steps behind each victim, swiftly loops the cord around the neck, and chokes each one to death. As they die their bodies are lifted into the grave and placed beside that of their master.

Once the six have been killed, the tempo changes. A parade of rulers, some of whom have come long distances to pay tribute to the dead chief step forward. One bears a three-foot-long sheet of rolled-up beaten copper that could only have come from the region around Lake Superior. With great ceremony he places it in the grave. Another chief steps up and, at his nod, bearers bring forth baskets of precious mica–totaling several bushels full—that came from near the Atlantic Ocean. This too goes into the grave.

Chiefs and subchiefs come forward carrying bundles of arrows tipped with stone points as finely crafted as jewelry. Some of the arrow points are of black chert from Arkansas and Oklahoma, others are of kaolin chert from southern Illinois, while still more are of stone from Tennessee and Wisconsin. I try to count the number of new shafted arrows that go into the grave and give up when the number reaches over a thousand.

The last objects placed in the grave are fifteen polished double-concave stone discs made of granite. Five inches in diameter, the rare stones are used in sporting events. These discs are among the most prized possessions of ruling chiefs and their tribes. This gift is a near unbelievable gesture of fealty to Cahokia’s gods. I glance at Anton for an explanation but he is staring at the discs as if mesmerized.

I realize that I am watching a fortune, a king’s ransom, being buried with this chief. Only the most powerful of leaders can command such a conspicuous consumption of grave goods. I think the event is over, but it is not. Again the mood changes. The murmuring has stopped and the crowd has fallen silent. I note that the bodies of the chief, those of the six murdered retainers, and the elaborate gifts do not begin to fill the excavated space and I wonder what other kind of tribute will be offered to demonstrate submission to the power of Cahokia and cement alliances with its powerful lord.

I do not have long to wait. The drumming resumes. A few cry out. There is a brief struggle and then two men appear from the crowd holding a young woman between them. She is made to stand at the edge of the pit while more young women are brought to stand beside her. When ten have been gathered, they are turned to face the grave. Then the man with the garrote goes down the line, quickly strangling each in turn. They struggle very little, as if resigned to their fate. As they die, their bodies are laid carefully in the grave, each one placed neatly next to her sister victim.

No sooner are the ten strangled and placed in the grave than ten more are lined up, and then ten more. The garroting does not stop until fifty young women, all between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three, have been killed. There is not enough room to line them all up in the grave so the bodies are stacked carefully on top of one another in layers. I am told that none of the young women are from Cahokia. All are tribute paid to the city by a distant chief.

The sun is near to setting when the last bodies are brought out of the charnel house. Four male corpses are lowered into the grave and positioned, side by side, with their arms overlapping in a comradely fashion. The puzzling aspect of their burial is that all four are missing their heads and hands.

As the sun sets and the air turns cooler, I sit alone by the river and ponder the meaning of what I have seen. The chief buried on the robe of beads in the shape of a falcon may represent the Sky World because raptors are powerful symbols of the sky. The man buried beneath him, facedown, may symbolize the Earth World. Can the four headless men represent the four directions, a number universally significant to the Indians of North America?

I wonder if the conspicuous display of gifts placed in the grave was competition among chieftains for the favor of the Lord of Cahokia. But who won the competition and what of the ritual deaths? Impressive as were the tributes of copper, mica, polished stones, and arrows, how can they compare with the gift of human lives? I pitch a stone into the black water and hope the young women believed themselves honored to have been selected to accompany the great chief on his journey to another life.

Both political and religious power, I decide, rules Cahokia– power that profoundly influences, if not controls, life over the region marked by the Mississippi River and its many tributaries. Some of Cahokia’s power comes from the fact that it is the first large population center to exist in North America. Its size alone, coupled with its trading network, impacts regions far beyond its apparent domain.

On this day in the year 1030 of the Common Era, Cahokia reigns as North America’s Rome, the locus of skilled agronomists, astronomer priests, engineers of enormous earthworks and stockades–the destination of awestruck worshippers who travel for hundreds of miles to see the sacred fires burning on the hilltops of the gods.

***

Mary Beth Norton

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

Mary Beth Norton, the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of American History at Cornell University, has written a number of books in early American history. Among them are The British-Americans; Liberty’s Daughters; Founding Mothers and Fathers, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; and In the Devil’s Snare, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in history and winner of the Ambassador Book Award in American Studies. Professor Norton is an elected fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In this essay Mary Beth Norton takes herself, and the reader, back to the Salem witch trials. In telling her story she dispels some myths and she tries to discover a few things that go beyond the existing historical evidence.

***

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

While I was researching and writing In the Devil’s Snare, my book on the Salem witch trials of 1692, I became utterly obsessed with witchcraft. Others have had analogous experiences, as John Demos, for example, reports in the preface of his 1982 book, Entertaining Satan. Some nights, I was so overwhelmed by the material I was reading that I tossed and turned sleeplessly for hours. For several years, every conversation I had with another historian seemed to end up being about witchcraft. During January through June of one year, I also thought it perfectly logical to compose a different message for my telephone answering machine each week, briefly explaining what had happened in Essex County, Massachusetts, on the same dates in 1692.

Only in retrospect have I realized how fully “bewitched” by my topic I was and come to understand that my friends had a point when they remarked that they found my ever-changing historical outgoing messages strange. (Other friends, though, fed my obsession by calling the house when they knew I’d be out, to obtain their weekly update on the latest news from 1692 Salem.)

Thus, not surprisingly, the historical event I would most like to have observed in person is the witchcraft crisis, especially the months between mid-January and late October 1692. Living through those months would surely have been emotionally draining, but such an experience would have answered many questions for modern scholars. Despite the hundreds of pages of surviving documents and many books by dedicated researchers, there is still much we don’t know about those days–and will probably never know, absent major new documentary discoveries.

***

To most Americans, the Salem witch trials serve today as a negative reference point–an example of hysterical fear blown out of all proportion to reality. In our collective consciousness, the trials have primarily become something to avoid replicating. Thus critics of, for instance, the impeachment of Bill Clinton or the 1980s charges against day-care providers for child sexual abuse have likened those prosecutions to witch hunts and specifically to the Salem trials. Arthur Miller’s well-known 1953 play, The Crucible, now frequently assigned in high school literature courses, inextricably linked the 1692 trials to the spate of anti-Communist hearings conducted in the early 1950s by the House Un-American Activities Committee and senators like Joseph McCarthy.

The seemingly modern relevance of the trials, coupled with past studies including ax grinding of a particular sort, have created a number of mistaken impressions of the trials in Americans’ minds. Scenes wholly from Miller’s imagination, for example, inform many Americans’ views of the events of 1692. Although such moments are vividly depicted in The Crucible, neither naked girls dancing in the woods while practicing voodoo nor an adulterous affair between Miller’s hero, John Proctor, and the Reverend Parris’s niece, Abigail Williams, appear anywhere in the surviving records. There is also no evidence that the witchcraft accusations represented an attempt by some people to steal other people’s land. Some descendants of convicted witches have contended that their ancestors were victimized by conspiracies of vengeful neighbors seeking to line their own pockets. Judging by questions I often receive after my lectures, one false notion is widely held: the belief that successful accusers of witches were rewarded by being given their victims’ landed estates. True, colonial officials could—but did not always—confiscate the personal property of executed witches, but any proceeds were to go to the crown, not to accusers. (In 1692, a greedy sheriff seized some personal property, but it is not clear what he did with it, nor was he involved in the initial accusations.) Lands and houses were not confiscated but instead descended to the heirs of those executed. Moreover, since many of the people hanged in 1692 were married women, they could not own property under coverture laws—when a woman married, all

her property passed to her husband. Thus an executed wife had no property that could have been turned over to anyone else, and in only one family were both husband and wife executed.

To understand the witchcraft crisis and what I would have gained by witnessing it, therefore, the first focus should be to recover what happened in 1692, ignoring the overlays of subsequent interpretations.(*)

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Such vivid detail it’s as if they were present.”

—New York Daily News

“Fun. . . . Poses new and intriguing questions. . . . The essays are crammed with knowledge and are as thought-provoking as they are entertaining.”

—Buffalo News

“Provocative essays that both scholars and history buffs can enjoy.”

—Deseret Morning News

—New York Daily News

“Fun. . . . Poses new and intriguing questions. . . . The essays are crammed with knowledge and are as thought-provoking as they are entertaining.”

—Buffalo News

“Provocative essays that both scholars and history buffs can enjoy.”

—Deseret Morning News

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Introduction by Byron Hollinshead

BILOINE W. YOUNG

A Say in Cahokia—AD1030

MARY BETH NORTON

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

CAROL BERKIN

George Washington and the Newburgh Conspiracy

JOSEPH J. ELLIS

The McGillivray Moment

CAROLYN GILMAN

Meriwether Lewis on the Divide

ROBERT V. REMINI

The Corrupt Bargain

PAUL C. NAGEL

The Amistad Trial

ROBERT W. JOHANNSEN

James K. Polk and the 1844 Election

Philip B. Kunhardt III

Jenny Lind’s American Debut, 1850

Thomas Fleming

WIth John Brown at Harpers Ferry

JAY WINIK

The Day Lincoln Was Shot

MARK STEVENS

Chief Joseph Surrenders

BERNARD WEISBERGER

La Follette Speaks against the War—1917

ROBERT COWLEY

The Road to Butgneville—November 11, 1918

JONATHAN RABB

Trying John Scopes

KEVIN BAKER

Lost-Found Nation: The Last Meeting between Elijah Muhammad and W. D. Fard

Geoffrey C. Ward

The Sick Man in the White House

ROBERT DALLEK

JFK and RFK Meet about Vietnam

CLAYBORNE CARSON

Memory, History, and the March on Washington

WILLIAM E. LEUCHTENBURG

Lyndon Johnson Confronts George Wallace

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Introduction by Byron Hollinshead

BILOINE W. YOUNG

A Say in Cahokia—AD1030

MARY BETH NORTON

The Salem Witchcraft Trials

CAROL BERKIN

George Washington and the Newburgh Conspiracy

JOSEPH J. ELLIS

The McGillivray Moment

CAROLYN GILMAN

Meriwether Lewis on the Divide

ROBERT V. REMINI

The Corrupt Bargain

PAUL C. NAGEL

The Amistad Trial

ROBERT W. JOHANNSEN

James K. Polk and the 1844 Election

Philip B. Kunhardt III

Jenny Lind’s American Debut, 1850

Thomas Fleming

WIth John Brown at Harpers Ferry

JAY WINIK

The Day Lincoln Was Shot

MARK STEVENS

Chief Joseph Surrenders

BERNARD WEISBERGER

La Follette Speaks against the War—1917

ROBERT COWLEY

The Road to Butgneville—November 11, 1918

JONATHAN RABB

Trying John Scopes

KEVIN BAKER

Lost-Found Nation: The Last Meeting between Elijah Muhammad and W. D. Fard

Geoffrey C. Ward

The Sick Man in the White House

ROBERT DALLEK

JFK and RFK Meet about Vietnam

CLAYBORNE CARSON

Memory, History, and the March on Washington

WILLIAM E. LEUCHTENBURG

Lyndon Johnson Confronts George Wallace

Acknowledgments

Illustration Credits

Descriere

Twenty of the finest interpreters of American history have been asked which event they would like to have witnessed in history and why. The result is this collection of essays that trains a lens on crucial moments of the past and brings them to vivid life.