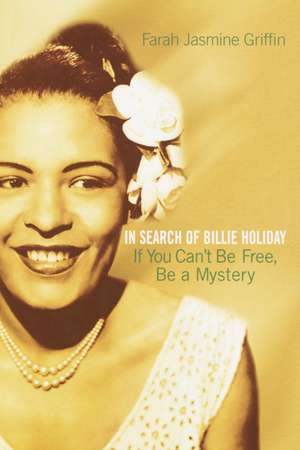

If You Can't Be Free, Be a Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday

Autor Farah Jasmine Griffinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2002

An intimate meditation on Holiday’s place in American culture and history, If You Can’t Be Free, Be A Mystery reveals Lady Day in all her complexity, humor and pain–a true jazz virtuoso whose passion and originality made every song she sang hers forever. Celebrated by poets, revered by recording artists from Frank Sinatra to Macy Gray, Billie Holiday is more popular and influential today than ever before. Now, thanks to this marvelous book, Holiday’s many fans can finally understand the singer and the woman they love.

Preț: 144.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 216

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.61€ • 30.00$ • 23.21£

27.61€ • 30.00$ • 23.21£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 17-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345449733

ISBN-10: 0345449738

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 141 x 207 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Book.

Editura: One World/Ballantine

ISBN-10: 0345449738

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 141 x 207 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Book.

Editura: One World/Ballantine

Notă biografică

A Billie Holiday fan for as long as she can remember, Farah Jasmine Griffin is currently a visiting professor at Columbia University. She is the author of “Who Set You Flowin’?”: The African American Migration Narrative.

Extras

Lady of the Day

My students love Mary J. Blige. I purchase her CDs, dance to the songs from the first one. I like her sass, appreciate her beauty, am charmed by her ghetto girl shyness, but I do not share their adoration of her. Two former students, Nikki and Malik, are especially passionate about her. Nikki cherishes what she sees as the honesty of her lyrics. "She's our Billie Holiday," Malik states emphatically. "Oh, please!" I think but do not say. Another, Salamishah, explains: "She captures all those moments in your life, like when you break up with someone. You feel her pain. You think 'Thank God; my pain isn't as bad as hers.' Each album is closer to what she wants to be, closer to what you want for her, closer to where you want to be too."

I love my students partly because they never stop believing in my capacity for growth. I have come to think when they speak about Mary J. Blige as their Billie Holiday, even more than the music, they mean the life; more than the voice, they refer to Holiday's life as they know it. And in this sense she may very well be their Billie Holiday. "She is one of ours, we want her to be happy, she sings for us, through us, to us." Does this comparison come out of any real sense of Holiday's life and the enormity of her talent or is it one that is constantly made for them in most media coverage of Blige's struggles?

Hip-hop journalist dream hampton has written of both Mary J. Blige and another contemporary black female vocalist, Erykah Badu, as artists with the potential to be modern-day Billie Holidays. Of Badu she writes, "Once you feel the vibration from the timbre of Erykah Badu's voice, you will understand immediately [the comparison] is no marketing ploy. In fact, a comparison to Billie could bear weight that no new singer would want to inherit. The expectations soar. The tragic life that was Lady Day's haunts." Here, Billie Holiday is a revered ancestor; however, the weight of being named her heir is doubly heavy: first because of the expectations of artistic achievement, and second because of the fear of the dire circumstances of her life and death.

In the case of Blige, hampton asserts, "practically everyone I poll says that Mary reminds them of Billie Holiday." Blige, however, is quick to distinguish herself from Holiday. When hampton asks her what word immediately comes to mind when she mentions Holiday, Blige responds: "Dead. Like Phyllis Hyman. Dead." She goes on:

I know that's hard. But the reason Phyllis and Billie are dead is 'cause they thought they could turn to a man or a drug for the love they needed. I'm not trying to preach, but that love, the love that makes you able to look in the mirror and be happy, that love comes from God.

It seems the more Blige tries to distance herself from Holiday, the more the media insists on making the comparison. At the end of the last century Notorious, the magazine published by Sean "Puffy" Combs, asked young contemporary artists to comment upon major celebrities of the twentieth century. Asked to comment on Holiday, Blige writes:

Our voices are similar in terms of style and the truth and the sadness in our music. But I refuse to be compared to Billie Holiday. Please compare me to the living. Don't compare me to the dead . . . I've seen the Diana Ross movie about her life and I have a collection of her music.

Death. Pain. Sadness. This is what Holiday signifies for this young artist, and she is terrified of the comparison. Her understanding of Holiday's life and legacy is formed by her interactions with the Diana Ross film and the dominant portrayals of her, so that Blige has every reason to be fearful. Elements of Holiday's life have been used to create a story that defines other black women artists such as Abbey Lincoln, Chaka Khan and Phyllis Hyman.

The one-dimensional Holiday with which Blige is familiar is a dangerous one. When an article on Chaka Khan opens by telling us that she sits beneath a poster of Billie Holiday, it is with the expectation that readers will conjure images of enormous talent, voracious appetites for drugs and self-destruction, even if these images are false ones. When a poet writes a tribute to Phyllis Hyman, who committed suicide, with allusions to Billie Holiday, we are asked to make similar connections.

How sad for us that this is all we believe we've inherited from Lady Day. The means by which these interpretations of her life are transmitted--movies, anecdotes, books--are all so powerful as to make this particular version seem ubiquitous.

Who was Billie Holiday? Why do we think of her only in terms of tragedy and failure? Are alternative interpretations of her life possible?

i.

The real musician is not the man who can knock your eyeballs out with fast, difficult runs. He's a real musician if he can make the simple songs vibrate and sparkle with the life that is within them.

--Julius Lester

For all the praise that Billie Holiday gets as a vocal stylist, she's seldom acknowledged as a musical genius. She was the first to prove that you could make soft sounds and still have a powerful emotional impact. She was understanding jazz long before Miles ever stuck a mute in his horn; she was the true "birth of cool."

--Cassandra Wilson

A people do not throw their geniuses away.

--Alice Walker

Billie Holiday was a musical genius. Until the recent celebrations of Nobel Prize Laureate Toni Morrison, few were willing to grant black women the title genius.6 Since the earliest days of our nation, black women were thought to be incapable of possessing genius; their achievements were considered the very opposite of intellectual accomplishment. All persons of African descent were thought to be unfit for advanced intellectual endeavor. Black women in particular were body, feeling, emotion and sexuality. This holds true even in comparison to white women; if white women's abilities were questioned and debated, their humanity was not.

Witness the case of Phillis Wheatley, the young slave girl born in West Africa. Reared by a master and mistress who taught her to read and write, she began writing poetry as a young teen and published her first book of verse, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston, in New England in 1773. It was the first book published by an African American. Wheatley demonstrated intellectual precociousness shortly after she was purchased at the age of seven. She quickly learned to read English and Latin, and she studied history and geography. Within four years of learning to speak English, she began to write poetry. Her book was introduced by a preface written by white sponsors, offering documents to authenticate her and to legitimize her poetry. Despite international acclaim, Wheatley's abilities were challenged by many, including Thomas Jefferson, who thought blacks capable only of passion, the basest of emotions, and at best, mimicry.

Billie Holiday was a poet of a different sort. If music is a language, then Holiday's careful juxtaposition of chosen notes structured into phrases that give both beauty and meaning, makes her a poet. Unlike Wheatley, however, Holiday wasn't doing something that black women just didn't do. She didn't enter into an arena where her right and ability to sing would be questioned. No, for many Americans it would have been no surprise that a colored girl could sing; couldn't they all? And unlike Wheatley, blacks did not try to play catch-up in the musical world Holiday inhabited; they set the standards. Still, the word "genius" applied to a black woman? For years jazz was not considered a "serious" art form. Once its seriousness was granted, only male musicians were considered geniuses. Few today would deny the "genius" of Charlie Parker or Miles Davis. After Holiday's death a small group of white male jazz critics began to discuss her talent in similar terms. For them, her genius was undisciplined, and sacrificed for her insatiable appetites; furthermore, these writers all suggest that Holiday herself had no understanding of her own gifts. Following the Holiday of these portraits there emerged a Holiday who was semiliterate, read only comic books, and was barely capable of understanding the meaning of the song "Strange Fruit."

I want to qualify my use of the word "genius." At times I exchange it with the word "brilliance," which seems to be a less loaded term. But I am not using genius in the romantic sense of that tormented yet inspired individual who stands above the rest of humanity. By genius I mean the special quality of mind and aptitudes that some individuals have innately for specific tasks or kinds of work. I also want to emphasize the intellectual nature of Holiday's talent, and the word "genius" helps me to do that. Contrary to what some observers would have you believe, she was not an idiot savant, capable of profound work in one artistic area but otherwise an intellectual imbecile. It is impossible for a gifted jazz musician to lack intelligence. Artistic success in this form requires talent, intelligence and discipline.

In spite of differing opinions regarding her intellectual capacities, most informed commentators agree that Holiday's musicianship was superb. Nonetheless, people less familiar with jazz often question her status as a "great" singer. Lady Day did not have the "pure," "pretty" voice of Ella or the incredible vocal range of Sarah. (While considered better singers, the genius of even these singers has gone unrecognized. Similarly, Aretha Franklin, who was a piano prodigy at the age of two, is rarely referred to as a genius.) She didn't scat, so it's harder for people to understand what it means when one says "Holiday sang like a horn" or that she was the "consummate jazz singer." Sassy's fans might say "Listen to Sarah trading fours with Clifford Brown, Paul Quinichette, Herbie Mann and others on 'Lullaby of Birdland' if you want to know what the voice as horn sounds like." Yes, I agree. I will not make claims about who was best; I like all three. However, I am partial to Lady for reasons I've explained. All three were queens, founding mothers of modern jazz singing. Each set a standard that has yet to be surpassed. But no one has to explain why Ella is so good, why Sarah is so good. It doesn't take much to recognize the sheer enormity of their talent, nor do you have to "understand" jazz to fully appreciate their art. It is a little harder for folks to get Lady Day.

All three women were extraordinary, but Lady was first, and her art and genius were so subtle and the choices she made so fine, so minute, that they often go unrecognized. Lady's singing style says "I'm going to take my time, be cool, laid back, ease on through, and I will still get there on time without sweating." She subtly redefined and recomposed as she worked, passing her songs first through her brain, then through her heart, and finally through her mouth as a gift for all of us to hear. Billie Holiday's sound was unique; while she modeled herself after Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith, she did not sound like them. Though she shared the clarity and diction of Ethel Waters, she doesn't sound like her either. So, while Holiday lacked Sarah Vaughan's range, Ella Fitzgerald's virtuosity and Bessie Smith's power, among them she had a unique sensitivity, timing, subtlety and fragility. Technically, she possessed the ability to bend notes exquisitely and she had an impeccable rhythmic sense: here she pushes the tempo, there she delays the entrance of a phrase. And she does so without ever losing momentum. After Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday was the next "major innovator" of jazz singing.

In addition, Billie Holiday sang lyrics with impeccable diction and clarity. Musical historian Eileen Southern notes early travelers' observations of black American women who mesmerized white children and adults with their story-telling. Holiday was a twentieth-century version of these women. She painted pictures and told stories through the songs she sang, spellbinding her audiences. In performance her charisma made each member of her audience feel as though she were singing directly to them, expressing exactly what they were feeling. Even during the final years of her life, when her voice was practically gone, Holiday was still capable of rendering a lyric with profound meaning and drama. Shirley Horn says, "Billie Holiday helped to show me that lyrics have got to mean something, have got to paint a picture, tell a story." There is a reason why we play her later recordings when we are feeling sad and lonely. Her voice seems to be in touch with our deepest emotions.

It is especially revealing to listen to the words of musicians who worked with Holiday, and to writers who have written about her craft. They best express how she created the music and they do so without technical jargon. They help explain what it is that makes her so unique, so important. These are the very reasons why we came to know her anyway.

Throughout her career, Billie Holiday worked with major jazz musicians, all of whom praised her musicianship and her artistry. They were among those who most appreciated the subtlety of her musical achievement. In many ways, she was a jazz musician's vocalist. Her early recordings in the thirties were with Teddy Wilson, a highly respected, classically trained jazz musician. Since Holiday, at the time, was a relative unknown outside of Harlem, these were released under Wilson's name. Even at this stage of her professional career, Wilson made note of her gifts. His description of their rehearsals suggests that, contrary to popular belief, Holiday did not just sit in front of a microphone and sing what she "felt":

I would get together with Billie first, and we would take a stack of music, maybe thirty, forty songs, and go through them, and pick out the ones that would appeal to her--the lyric, the melody. And after we picked them, we'd concentrate on the ones we were going to record. And we rehearsed them until she had a very good idea of them in her mind, in her ear. . . . Her ear was phenomenal, but she had to get a song into her ear so she could do her own style on it. She would invent different little phrases that would be different melody notes from the ones that were written.

In this description, Wilson reveals several important aspects of Holiday's artistry. Like the best instrumentalists, Holiday patiently rehearsed songs as they were written so that she could have them in her head and her ear. She was later able to improvise on the melody because she knew the song so well. Holiday would remember all of the songs they rehearsed--not an easy feat. In addition to her talent, the passage reveals her sense of discipline and practice.

My students love Mary J. Blige. I purchase her CDs, dance to the songs from the first one. I like her sass, appreciate her beauty, am charmed by her ghetto girl shyness, but I do not share their adoration of her. Two former students, Nikki and Malik, are especially passionate about her. Nikki cherishes what she sees as the honesty of her lyrics. "She's our Billie Holiday," Malik states emphatically. "Oh, please!" I think but do not say. Another, Salamishah, explains: "She captures all those moments in your life, like when you break up with someone. You feel her pain. You think 'Thank God; my pain isn't as bad as hers.' Each album is closer to what she wants to be, closer to what you want for her, closer to where you want to be too."

I love my students partly because they never stop believing in my capacity for growth. I have come to think when they speak about Mary J. Blige as their Billie Holiday, even more than the music, they mean the life; more than the voice, they refer to Holiday's life as they know it. And in this sense she may very well be their Billie Holiday. "She is one of ours, we want her to be happy, she sings for us, through us, to us." Does this comparison come out of any real sense of Holiday's life and the enormity of her talent or is it one that is constantly made for them in most media coverage of Blige's struggles?

Hip-hop journalist dream hampton has written of both Mary J. Blige and another contemporary black female vocalist, Erykah Badu, as artists with the potential to be modern-day Billie Holidays. Of Badu she writes, "Once you feel the vibration from the timbre of Erykah Badu's voice, you will understand immediately [the comparison] is no marketing ploy. In fact, a comparison to Billie could bear weight that no new singer would want to inherit. The expectations soar. The tragic life that was Lady Day's haunts." Here, Billie Holiday is a revered ancestor; however, the weight of being named her heir is doubly heavy: first because of the expectations of artistic achievement, and second because of the fear of the dire circumstances of her life and death.

In the case of Blige, hampton asserts, "practically everyone I poll says that Mary reminds them of Billie Holiday." Blige, however, is quick to distinguish herself from Holiday. When hampton asks her what word immediately comes to mind when she mentions Holiday, Blige responds: "Dead. Like Phyllis Hyman. Dead." She goes on:

I know that's hard. But the reason Phyllis and Billie are dead is 'cause they thought they could turn to a man or a drug for the love they needed. I'm not trying to preach, but that love, the love that makes you able to look in the mirror and be happy, that love comes from God.

It seems the more Blige tries to distance herself from Holiday, the more the media insists on making the comparison. At the end of the last century Notorious, the magazine published by Sean "Puffy" Combs, asked young contemporary artists to comment upon major celebrities of the twentieth century. Asked to comment on Holiday, Blige writes:

Our voices are similar in terms of style and the truth and the sadness in our music. But I refuse to be compared to Billie Holiday. Please compare me to the living. Don't compare me to the dead . . . I've seen the Diana Ross movie about her life and I have a collection of her music.

Death. Pain. Sadness. This is what Holiday signifies for this young artist, and she is terrified of the comparison. Her understanding of Holiday's life and legacy is formed by her interactions with the Diana Ross film and the dominant portrayals of her, so that Blige has every reason to be fearful. Elements of Holiday's life have been used to create a story that defines other black women artists such as Abbey Lincoln, Chaka Khan and Phyllis Hyman.

The one-dimensional Holiday with which Blige is familiar is a dangerous one. When an article on Chaka Khan opens by telling us that she sits beneath a poster of Billie Holiday, it is with the expectation that readers will conjure images of enormous talent, voracious appetites for drugs and self-destruction, even if these images are false ones. When a poet writes a tribute to Phyllis Hyman, who committed suicide, with allusions to Billie Holiday, we are asked to make similar connections.

How sad for us that this is all we believe we've inherited from Lady Day. The means by which these interpretations of her life are transmitted--movies, anecdotes, books--are all so powerful as to make this particular version seem ubiquitous.

Who was Billie Holiday? Why do we think of her only in terms of tragedy and failure? Are alternative interpretations of her life possible?

i.

The real musician is not the man who can knock your eyeballs out with fast, difficult runs. He's a real musician if he can make the simple songs vibrate and sparkle with the life that is within them.

--Julius Lester

For all the praise that Billie Holiday gets as a vocal stylist, she's seldom acknowledged as a musical genius. She was the first to prove that you could make soft sounds and still have a powerful emotional impact. She was understanding jazz long before Miles ever stuck a mute in his horn; she was the true "birth of cool."

--Cassandra Wilson

A people do not throw their geniuses away.

--Alice Walker

Billie Holiday was a musical genius. Until the recent celebrations of Nobel Prize Laureate Toni Morrison, few were willing to grant black women the title genius.6 Since the earliest days of our nation, black women were thought to be incapable of possessing genius; their achievements were considered the very opposite of intellectual accomplishment. All persons of African descent were thought to be unfit for advanced intellectual endeavor. Black women in particular were body, feeling, emotion and sexuality. This holds true even in comparison to white women; if white women's abilities were questioned and debated, their humanity was not.

Witness the case of Phillis Wheatley, the young slave girl born in West Africa. Reared by a master and mistress who taught her to read and write, she began writing poetry as a young teen and published her first book of verse, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston, in New England in 1773. It was the first book published by an African American. Wheatley demonstrated intellectual precociousness shortly after she was purchased at the age of seven. She quickly learned to read English and Latin, and she studied history and geography. Within four years of learning to speak English, she began to write poetry. Her book was introduced by a preface written by white sponsors, offering documents to authenticate her and to legitimize her poetry. Despite international acclaim, Wheatley's abilities were challenged by many, including Thomas Jefferson, who thought blacks capable only of passion, the basest of emotions, and at best, mimicry.

Billie Holiday was a poet of a different sort. If music is a language, then Holiday's careful juxtaposition of chosen notes structured into phrases that give both beauty and meaning, makes her a poet. Unlike Wheatley, however, Holiday wasn't doing something that black women just didn't do. She didn't enter into an arena where her right and ability to sing would be questioned. No, for many Americans it would have been no surprise that a colored girl could sing; couldn't they all? And unlike Wheatley, blacks did not try to play catch-up in the musical world Holiday inhabited; they set the standards. Still, the word "genius" applied to a black woman? For years jazz was not considered a "serious" art form. Once its seriousness was granted, only male musicians were considered geniuses. Few today would deny the "genius" of Charlie Parker or Miles Davis. After Holiday's death a small group of white male jazz critics began to discuss her talent in similar terms. For them, her genius was undisciplined, and sacrificed for her insatiable appetites; furthermore, these writers all suggest that Holiday herself had no understanding of her own gifts. Following the Holiday of these portraits there emerged a Holiday who was semiliterate, read only comic books, and was barely capable of understanding the meaning of the song "Strange Fruit."

I want to qualify my use of the word "genius." At times I exchange it with the word "brilliance," which seems to be a less loaded term. But I am not using genius in the romantic sense of that tormented yet inspired individual who stands above the rest of humanity. By genius I mean the special quality of mind and aptitudes that some individuals have innately for specific tasks or kinds of work. I also want to emphasize the intellectual nature of Holiday's talent, and the word "genius" helps me to do that. Contrary to what some observers would have you believe, she was not an idiot savant, capable of profound work in one artistic area but otherwise an intellectual imbecile. It is impossible for a gifted jazz musician to lack intelligence. Artistic success in this form requires talent, intelligence and discipline.

In spite of differing opinions regarding her intellectual capacities, most informed commentators agree that Holiday's musicianship was superb. Nonetheless, people less familiar with jazz often question her status as a "great" singer. Lady Day did not have the "pure," "pretty" voice of Ella or the incredible vocal range of Sarah. (While considered better singers, the genius of even these singers has gone unrecognized. Similarly, Aretha Franklin, who was a piano prodigy at the age of two, is rarely referred to as a genius.) She didn't scat, so it's harder for people to understand what it means when one says "Holiday sang like a horn" or that she was the "consummate jazz singer." Sassy's fans might say "Listen to Sarah trading fours with Clifford Brown, Paul Quinichette, Herbie Mann and others on 'Lullaby of Birdland' if you want to know what the voice as horn sounds like." Yes, I agree. I will not make claims about who was best; I like all three. However, I am partial to Lady for reasons I've explained. All three were queens, founding mothers of modern jazz singing. Each set a standard that has yet to be surpassed. But no one has to explain why Ella is so good, why Sarah is so good. It doesn't take much to recognize the sheer enormity of their talent, nor do you have to "understand" jazz to fully appreciate their art. It is a little harder for folks to get Lady Day.

All three women were extraordinary, but Lady was first, and her art and genius were so subtle and the choices she made so fine, so minute, that they often go unrecognized. Lady's singing style says "I'm going to take my time, be cool, laid back, ease on through, and I will still get there on time without sweating." She subtly redefined and recomposed as she worked, passing her songs first through her brain, then through her heart, and finally through her mouth as a gift for all of us to hear. Billie Holiday's sound was unique; while she modeled herself after Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith, she did not sound like them. Though she shared the clarity and diction of Ethel Waters, she doesn't sound like her either. So, while Holiday lacked Sarah Vaughan's range, Ella Fitzgerald's virtuosity and Bessie Smith's power, among them she had a unique sensitivity, timing, subtlety and fragility. Technically, she possessed the ability to bend notes exquisitely and she had an impeccable rhythmic sense: here she pushes the tempo, there she delays the entrance of a phrase. And she does so without ever losing momentum. After Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday was the next "major innovator" of jazz singing.

In addition, Billie Holiday sang lyrics with impeccable diction and clarity. Musical historian Eileen Southern notes early travelers' observations of black American women who mesmerized white children and adults with their story-telling. Holiday was a twentieth-century version of these women. She painted pictures and told stories through the songs she sang, spellbinding her audiences. In performance her charisma made each member of her audience feel as though she were singing directly to them, expressing exactly what they were feeling. Even during the final years of her life, when her voice was practically gone, Holiday was still capable of rendering a lyric with profound meaning and drama. Shirley Horn says, "Billie Holiday helped to show me that lyrics have got to mean something, have got to paint a picture, tell a story." There is a reason why we play her later recordings when we are feeling sad and lonely. Her voice seems to be in touch with our deepest emotions.

It is especially revealing to listen to the words of musicians who worked with Holiday, and to writers who have written about her craft. They best express how she created the music and they do so without technical jargon. They help explain what it is that makes her so unique, so important. These are the very reasons why we came to know her anyway.

Throughout her career, Billie Holiday worked with major jazz musicians, all of whom praised her musicianship and her artistry. They were among those who most appreciated the subtlety of her musical achievement. In many ways, she was a jazz musician's vocalist. Her early recordings in the thirties were with Teddy Wilson, a highly respected, classically trained jazz musician. Since Holiday, at the time, was a relative unknown outside of Harlem, these were released under Wilson's name. Even at this stage of her professional career, Wilson made note of her gifts. His description of their rehearsals suggests that, contrary to popular belief, Holiday did not just sit in front of a microphone and sing what she "felt":

I would get together with Billie first, and we would take a stack of music, maybe thirty, forty songs, and go through them, and pick out the ones that would appeal to her--the lyric, the melody. And after we picked them, we'd concentrate on the ones we were going to record. And we rehearsed them until she had a very good idea of them in her mind, in her ear. . . . Her ear was phenomenal, but she had to get a song into her ear so she could do her own style on it. She would invent different little phrases that would be different melody notes from the ones that were written.

In this description, Wilson reveals several important aspects of Holiday's artistry. Like the best instrumentalists, Holiday patiently rehearsed songs as they were written so that she could have them in her head and her ear. She was later able to improvise on the melody because she knew the song so well. Holiday would remember all of the songs they rehearsed--not an easy feat. In addition to her talent, the passage reveals her sense of discipline and practice.

Recenzii

“This exquisite look at Lady Day is priceless.”

–Essence

“DAZZLING . . . THIS BOOK CONTAINS WRITING AS HAUNTING AND EVOCATIVE AS BILLIE HOLIDAY’S VOICE.”

–ANN DOUGLAS

Author of Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s

“[AN] AMBITIOUS, FREE-RANGING MEDITATION ON THE SINGER’S LEGACY . . . Griffin’s prose is both sentimental and intellectual. . . . Her observations are sound and illuminating.”

–The Washington Post

–Essence

“DAZZLING . . . THIS BOOK CONTAINS WRITING AS HAUNTING AND EVOCATIVE AS BILLIE HOLIDAY’S VOICE.”

–ANN DOUGLAS

Author of Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s

“[AN] AMBITIOUS, FREE-RANGING MEDITATION ON THE SINGER’S LEGACY . . . Griffin’s prose is both sentimental and intellectual. . . . Her observations are sound and illuminating.”

–The Washington Post

Descriere

This fascinating meditation on Billie Holiday, her world, and how she is remembered at last liberates Lady Day from the mythology of the "tragic songstress" that has obscured both her life and her art.