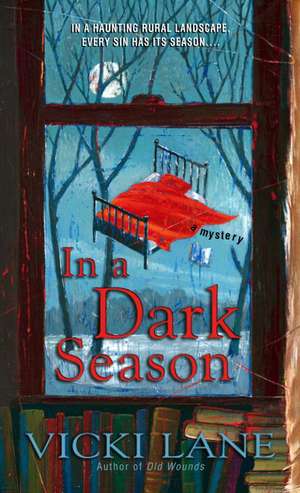

In a Dark Season: The Elizabeth Goodweather Appalachian Mysteries

Autor Vicki Laneen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Anthony Awards (2009)

Nola Barrett’s ancient, sprawling house is spewing a dark past: of depravity, scandal and murder. Her land is at the center of multiple mysteries, ranging from a suspicious death to the brutal rape of a young woman to the legend of a handsome youth hanged for murder. But with Nola recovering from her self-inflicted wounds, Elizabeth has inherited her mad, violent drama—while a killer has a perfect view of it all.…

Preț: 46.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.98€ • 9.48$ • 7.47£

8.98€ • 9.48$ • 7.47£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440243601

ISBN-10: 0440243602

Pagini: 430

Dimensiuni: 105 x 175 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Dell Publishing Company

Seria The Elizabeth Goodweather Appalachian Mysteries

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0440243602

Pagini: 430

Dimensiuni: 105 x 175 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Dell Publishing Company

Seria The Elizabeth Goodweather Appalachian Mysteries

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Notă biografică

Vicki Lane has lived with her family on a mountain farm in North Carolina since 1975. She is at work on an addition to the saga of Elizabeth’s Marshall County.

Extras

Chapter One

The Palimpsest

Friday, December 1

The madwoman whispered into the blue shadows of a wintry afternoon. Icy wind caught at her hair, loosing it to whip her cheeks and sting her half-closed eyes. Pushing aside the long black strands, she peered through the fragile railing of the upper porch. Below, the fieldstone walkway with its humped border of snow-hooded dark boxwoods curled about the house. Beyond the walkway the land sloped away, down to the railroad tracks and the gray river where icy foam spattered on black rocks and a perpetual roar filled the air.

Her hand clutching the flimsy balustrade and her gaze fixed on the stony path far below, the madwoman pulled herself to her feet. Behind her, a door rattled on its rusty hinges and slammed, only to creak open again.

She paused, aware of the loom of the house around her—feeling it waiting, crouching there on its ledge above the swift-flowing river. The brown skeletons of the kudzu that draped the walls and chimneys rustled in a dry undertone, the once lush vines shriveled to a delicate netting that meshed the peeling clapboards and spider-webbed the cracked and cloudy windowpanes. From every side, in small mutterings and rustlings, the old house spoke.

None escape. None.

As the verdict throbbed in her ears, marking time with the pulse of blood, the madwoman began to feel her cautious way along the uneven planks of the second-story porch. A loose board caught at her shoe and she staggered, putting out a thin hand to the wall where missing clapboards revealed a layer of brick-printed asphalt siding, the rough material curling back at an uncovered seam.

Compelled by some urgent desire, she caught at the torn edge, tugging, peeling it from the wood beneath, ripping away the siding to expose the heart of the house—the original structure beneath the accretions of later years.

She splayed her trembling fingers against the massive chestnut logs and squeezed her eyes shut. A palimpsest, layer hiding layer, wrong concealing wrong. If I could tear you down, board by board, log by log, would I ever discover where the evil lies . . . or where it began? Resting her forehead against the wood's immovable curve, she allowed the memories to fill her: the history of the house, the subtext of her life.

The logs have seen it all. Their story flowed into her, through her head and fingertips, as she leaned against them, breathing the dust-dry hint of fragrance. The men who felled the trees and built this house, the drovers who passed this way, the farmers, the travelers, the men who took their money, the women who lured them . . . and Belle, so much of Belle remains. Her dark spirit is in these logs, this house, this land. Why did I think that I and mine could escape?

No answer came, only the mocking echoes of memories. The thrum of blood in her ears grew louder and the madwoman turned her back on the exposed logs of the house wall to move to the railing. Leaning out, oblivious to the cutting wind, she fixed her eyes on the stony path thirty feet below. Far enough? She hesitated, looking up and down the porch. A stack of plastic milk crates, filled with black-mottled shapes, caught her eye.

Of course there would be a way. The house will see to it. Belle will see to it.

Snatching up the topmost crate, she lifted it to the porch railing. Dried and mildew-speckled, the gourds tumbled down to shatter on the stones, scattering seeds over the path and frozen ground. The madwoman set the empty crate beside the balusters and slowly, painfully, pulled herself up to stand on its red grating-like surface. Then she placed a tentative foot on the wide railing.

The words came to her, dredged from memory's storehouse. As always, when her own thoughts faltered, one of the poets spoke for her, one of the many whose works she had loved and learned and taught.

Balanced on the railing, the madwoman hurled the words into the wind's face.

"After great pain, a formal feeling comes—"

She broke off, unable at first to continue, then, gathering strength, she forced her lips to form the words, speaking the closing lines into the bitter afternoon.

". . . The Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go."

The house waited.

Chapter Two

Three Dolls

Friday, December 1

The three naked baby dolls, their pudgy bodies stained with age and weather, twisted and danced in the winter wind like a grisly chorus line. As the car negotiated the twisting road down to the river, Elizabeth Goodweather saw them once more. They had hung there as long as she could remember, dangling by their almost nonexistent necks from the clothesline that sagged along the back porch of the old house called Gudger's Stand.

The house lay below a curve so hairpin-sharp and a road so narrow that many travelers, intent on avoiding the deep ditch to one side and the sheer drop to the other, never noticed the house at all. It was easy to miss, seated as it was in a tangle of saplings, weedy brush, and household garbage, perched well below the level of the pavement on a narrow bank that fell away to the river.

I wish I'd never noticed it. It wasn't until the power company cleared some of those big trees that you could even see the house.

Her first sight of the house and its cruel row of hanged dolls had been on a fall day sixteen years back. It was Rosie's first year in high school. Sam was still alive. He was driving and our girls were in the back seat. . . .

The memory was piercing: the sudden appearance of the hitherto-unseen house with its long porches front and back; the pathetic dolls and the hunched old man sitting in a chair beneath them, belaboring their rubber bodies with his lifted cane. And a woman just disappearing into the house; I only saw the tail of her skirt as she went through the door. The whole scene was bizarre—and unlike anything else I'd seen in Marshall County. I started to say something to Sam but then I couldn't; it just seemed too awful—those helpless little baby dolls—I didn't want the girls to see that old man hitting the dolls.

Ridiculous, of course. The very next time the girls had ridden their school buses, ghoulishly eager friends had pointed out the newly visible house and the trio of dangling dolls. As they downed their after-school snacks, Rosemary and Laurel had discussed the display with eager cheerfulness.

"Shawn says it's where old man Randall Revis lives—and that he's had three wives and all of them have run off. So old man Revis named the dolls for his ex-wives and he whacks them with his walking stick."

Rosemary's matter-of-fact explanation, punctuated by slurps of ramen noodles, was followed by her younger sister's assertion that a girl on her bus had said the old man was a cannibal who lured children into his house and cut them up and put them in his big freezer.

"Like the witch in 'Hansel and Gretel'! And every time he eats one, he hangs up another doll!" Laurel's eyes had been wide but then she had smiled knowingly. "That's not true, is it, Mum? That girl was just trying to scare the little kids, wasn't she?"

"That's what it sounds like to me, Laurie." Elizabeth had been quick to agree, adding a tentative explanation about a sick old man, not right in the head.

But really, the girls just took it in stride as one of those inexplicable things grown-ups do. I think they even stopped seeing the house and the dolls. I wish I could have. For some reason I always have to look, and I'm always hoping that the dolls or the cords holding them will have rotted and fallen away. Or that the kudzu will have finally covered the whole place. The old man's been dead for years now; you'd think someone would have taken those dolls down.

Elizabeth shuddered and forced her thoughts back to the here and now. Sam was six years dead; their daughters were grown; it was Phillip Hawkins at the wheel of her car on this particular winter afternoon. But still the sight of the hanging dolls made her shudder.

"What's the matter, Lizabeth?" Without taking his eyes from the road, Phillip reached out to tug at her long braid. One-handed, he steered the jeep down the corkscrew road and toward the bridge over the river at Gudger's Stand. Snowplows had been out early: tarnished ridges of frozen white from the unseasonable storm of the previous night lined the road ahead.

She caught at his free hand, happy to be pulled from her uneasy reverie. "It's just that old house—it always gives me the creeps."

Phillip turned into the deserted parking lot to the left of the road. For much of the year, the flat area at the base of the bridge swarmed with kayakers, rafters, and busloads of customers for the white-water rafting companies, but on this frigid day, it was deserted except for a pair of Canada geese, fluffed out against the cold.

"That one up there?" Phillip wheeled the jeep in a tight circle, bringing it to a stop facing away from the river and toward the house.

She nodded. "That one. It's as near to being a haunted house as anything we have around here—folks tell all kinds of creepy stories about things that happened there in the past—and ten years ago the old man who lived there was murdered in his bed. They've never found out who did it."

They sat in the still-rumbling car, gazing up the snow-covered slope to the dilapidated and abandoned house. Low-lying clouds washed the scene in grim tones of pale gray and faded brown.

"What's that?" Elizabeth leaned closer to the windshield, pointing to a dark shape that seemed to quiver behind the railings at the end of the upper porch. "Do you see it? There's something moving up there!"

"Probably just something blowing in the wind." Phillip followed her gaze. "One of those big black trash bags maybe—"

"No, I don't think so." Elizabeth frowned, struggling to make sense of the dark form that had moved now to lean against the wall of the old house. "It's a person. But what would anyone . . . I wish I could see—"

Phillip was already pulling out of the lot and toward the overgrown driveway that led up to the house. And even as he said "Something's not right here," the angular shape moved toward the porch railing. There was a flash of red and a tangle of rounded objects fell to the ground.

"It's a woman up there." Elizabeth craned her neck to get a better look at the figure high above them. "What's she doing . . . climbing up on something or . . . ?"

The question in her voice turned to horror. "Phillip! I think she's going to jump!"

The car was halfway up the driveway when they were halted by a downed tree lying across the overgrown ruts. High above them they could see the woman balanced on the railing. One arm around a porch pillar, she swayed in the wind.

Elizabeth shoved her door open and leaped from the car. Pulling on her jacket as she ran, she pounded up the steep drive, skidding treacherously on the frozen mud and ice-covered puddles. Behind her, she could hear the steady thud of Phillip's boots. Ahead she could see the scarecrow form of the woman, teetering on her precarious perch. Black hair writhed around her head, obscuring her face, and a long black coat lofted out in the wind, making her look like some great bird preparing for flight.

"Stop!" Elizabeth's voice was little more than a thin quaver against the wind, and she took a breath and tried again. "Please! . . . Wait! . . . Talk to us!"

This time her cry reached the woman on the railing, who turned at the sound. Her pale face stared at Elizabeth and her lips moved, but the words, if there were words, were carried away by the pitiless wind.

Elizabeth gasped. "Nola!"

She tried to run faster, even as she shouted to the figure high above her. "It's me, Nola—Elizabeth Goodweather. Please, get down from there before—"

The woman on the railing hesitated, wavered. Then she lifted her head as if listening to a faraway sound.

"Nola! Wait where you are, please! We'll help you . . ." Elizabeth's side was aching and her voice was a rasping croak, but she forced herself up the road and toward the old house. In the distance, a siren began its urgent howl.

Phillip was at her side now, pointing to the stairs that led to the upper porch. "Keep talking to her; I'll try to get up there."

The siren was louder now, very near.

"Nola, let us help you!" She kept moving toward the porch, laboring to be heard, to be understood, to get closer, to make eye contact with this woman she had met only a few months before. "Please, be careful; that railing looks—"

Above her the black-haired woman slowly shook her head. Elizabeth heard the emergency vehicle turn into the drive behind her. The siren shrieked once more, then died away.

She turned to see a Marshall County sheriff's car stopped just behind her jeep. Its light was pulsing in blue rhythmic bursts as two men, followed by a smaller figure in jeans and a purple fleece jacket, emerged from its interior and began to race up the drive.

Whirling to see what effect this new arrival would have, Elizabeth was just in time to see the black-clad figure release her hold on the post, spread her arms wide, and plunge—a great ungainly raven tumbling from the sky.

"How the hell she survived . . . if it hadn't been for one of those old boxwoods breaking her fall before she hit the stone walk . . ."

The EMTs had responded swiftly, strapping the crumpled, unconscious body of Miss Nola Barrett to a backboard and loading her into the ambulance for the trip to an Asheville emergency room. The young woman in the purple jacket had gone with Miss Barrett.

"She's the one who called us," Sheriff Mackenzie Blaine had explained. "Miss Barrett's niece or something—been visiting her aunt. She said Miss Barrett's started acting kind of squirrelly—obsessing about this house. Evidently the house belongs to Miss Barrett—or she thinks it does. Anyway, the niece—what's her name, Trace, Tracy?—said she went to the store after lunch and when she came back, her aunt was gone. She found footprints on the trail leading down this way and was concerned that Miss Barrett might be going to . . . to hurt herself."

The Palimpsest

Friday, December 1

The madwoman whispered into the blue shadows of a wintry afternoon. Icy wind caught at her hair, loosing it to whip her cheeks and sting her half-closed eyes. Pushing aside the long black strands, she peered through the fragile railing of the upper porch. Below, the fieldstone walkway with its humped border of snow-hooded dark boxwoods curled about the house. Beyond the walkway the land sloped away, down to the railroad tracks and the gray river where icy foam spattered on black rocks and a perpetual roar filled the air.

Her hand clutching the flimsy balustrade and her gaze fixed on the stony path far below, the madwoman pulled herself to her feet. Behind her, a door rattled on its rusty hinges and slammed, only to creak open again.

She paused, aware of the loom of the house around her—feeling it waiting, crouching there on its ledge above the swift-flowing river. The brown skeletons of the kudzu that draped the walls and chimneys rustled in a dry undertone, the once lush vines shriveled to a delicate netting that meshed the peeling clapboards and spider-webbed the cracked and cloudy windowpanes. From every side, in small mutterings and rustlings, the old house spoke.

None escape. None.

As the verdict throbbed in her ears, marking time with the pulse of blood, the madwoman began to feel her cautious way along the uneven planks of the second-story porch. A loose board caught at her shoe and she staggered, putting out a thin hand to the wall where missing clapboards revealed a layer of brick-printed asphalt siding, the rough material curling back at an uncovered seam.

Compelled by some urgent desire, she caught at the torn edge, tugging, peeling it from the wood beneath, ripping away the siding to expose the heart of the house—the original structure beneath the accretions of later years.

She splayed her trembling fingers against the massive chestnut logs and squeezed her eyes shut. A palimpsest, layer hiding layer, wrong concealing wrong. If I could tear you down, board by board, log by log, would I ever discover where the evil lies . . . or where it began? Resting her forehead against the wood's immovable curve, she allowed the memories to fill her: the history of the house, the subtext of her life.

The logs have seen it all. Their story flowed into her, through her head and fingertips, as she leaned against them, breathing the dust-dry hint of fragrance. The men who felled the trees and built this house, the drovers who passed this way, the farmers, the travelers, the men who took their money, the women who lured them . . . and Belle, so much of Belle remains. Her dark spirit is in these logs, this house, this land. Why did I think that I and mine could escape?

No answer came, only the mocking echoes of memories. The thrum of blood in her ears grew louder and the madwoman turned her back on the exposed logs of the house wall to move to the railing. Leaning out, oblivious to the cutting wind, she fixed her eyes on the stony path thirty feet below. Far enough? She hesitated, looking up and down the porch. A stack of plastic milk crates, filled with black-mottled shapes, caught her eye.

Of course there would be a way. The house will see to it. Belle will see to it.

Snatching up the topmost crate, she lifted it to the porch railing. Dried and mildew-speckled, the gourds tumbled down to shatter on the stones, scattering seeds over the path and frozen ground. The madwoman set the empty crate beside the balusters and slowly, painfully, pulled herself up to stand on its red grating-like surface. Then she placed a tentative foot on the wide railing.

The words came to her, dredged from memory's storehouse. As always, when her own thoughts faltered, one of the poets spoke for her, one of the many whose works she had loved and learned and taught.

Balanced on the railing, the madwoman hurled the words into the wind's face.

"After great pain, a formal feeling comes—"

She broke off, unable at first to continue, then, gathering strength, she forced her lips to form the words, speaking the closing lines into the bitter afternoon.

". . . The Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go."

The house waited.

Chapter Two

Three Dolls

Friday, December 1

The three naked baby dolls, their pudgy bodies stained with age and weather, twisted and danced in the winter wind like a grisly chorus line. As the car negotiated the twisting road down to the river, Elizabeth Goodweather saw them once more. They had hung there as long as she could remember, dangling by their almost nonexistent necks from the clothesline that sagged along the back porch of the old house called Gudger's Stand.

The house lay below a curve so hairpin-sharp and a road so narrow that many travelers, intent on avoiding the deep ditch to one side and the sheer drop to the other, never noticed the house at all. It was easy to miss, seated as it was in a tangle of saplings, weedy brush, and household garbage, perched well below the level of the pavement on a narrow bank that fell away to the river.

I wish I'd never noticed it. It wasn't until the power company cleared some of those big trees that you could even see the house.

Her first sight of the house and its cruel row of hanged dolls had been on a fall day sixteen years back. It was Rosie's first year in high school. Sam was still alive. He was driving and our girls were in the back seat. . . .

The memory was piercing: the sudden appearance of the hitherto-unseen house with its long porches front and back; the pathetic dolls and the hunched old man sitting in a chair beneath them, belaboring their rubber bodies with his lifted cane. And a woman just disappearing into the house; I only saw the tail of her skirt as she went through the door. The whole scene was bizarre—and unlike anything else I'd seen in Marshall County. I started to say something to Sam but then I couldn't; it just seemed too awful—those helpless little baby dolls—I didn't want the girls to see that old man hitting the dolls.

Ridiculous, of course. The very next time the girls had ridden their school buses, ghoulishly eager friends had pointed out the newly visible house and the trio of dangling dolls. As they downed their after-school snacks, Rosemary and Laurel had discussed the display with eager cheerfulness.

"Shawn says it's where old man Randall Revis lives—and that he's had three wives and all of them have run off. So old man Revis named the dolls for his ex-wives and he whacks them with his walking stick."

Rosemary's matter-of-fact explanation, punctuated by slurps of ramen noodles, was followed by her younger sister's assertion that a girl on her bus had said the old man was a cannibal who lured children into his house and cut them up and put them in his big freezer.

"Like the witch in 'Hansel and Gretel'! And every time he eats one, he hangs up another doll!" Laurel's eyes had been wide but then she had smiled knowingly. "That's not true, is it, Mum? That girl was just trying to scare the little kids, wasn't she?"

"That's what it sounds like to me, Laurie." Elizabeth had been quick to agree, adding a tentative explanation about a sick old man, not right in the head.

But really, the girls just took it in stride as one of those inexplicable things grown-ups do. I think they even stopped seeing the house and the dolls. I wish I could have. For some reason I always have to look, and I'm always hoping that the dolls or the cords holding them will have rotted and fallen away. Or that the kudzu will have finally covered the whole place. The old man's been dead for years now; you'd think someone would have taken those dolls down.

Elizabeth shuddered and forced her thoughts back to the here and now. Sam was six years dead; their daughters were grown; it was Phillip Hawkins at the wheel of her car on this particular winter afternoon. But still the sight of the hanging dolls made her shudder.

"What's the matter, Lizabeth?" Without taking his eyes from the road, Phillip reached out to tug at her long braid. One-handed, he steered the jeep down the corkscrew road and toward the bridge over the river at Gudger's Stand. Snowplows had been out early: tarnished ridges of frozen white from the unseasonable storm of the previous night lined the road ahead.

She caught at his free hand, happy to be pulled from her uneasy reverie. "It's just that old house—it always gives me the creeps."

Phillip turned into the deserted parking lot to the left of the road. For much of the year, the flat area at the base of the bridge swarmed with kayakers, rafters, and busloads of customers for the white-water rafting companies, but on this frigid day, it was deserted except for a pair of Canada geese, fluffed out against the cold.

"That one up there?" Phillip wheeled the jeep in a tight circle, bringing it to a stop facing away from the river and toward the house.

She nodded. "That one. It's as near to being a haunted house as anything we have around here—folks tell all kinds of creepy stories about things that happened there in the past—and ten years ago the old man who lived there was murdered in his bed. They've never found out who did it."

They sat in the still-rumbling car, gazing up the snow-covered slope to the dilapidated and abandoned house. Low-lying clouds washed the scene in grim tones of pale gray and faded brown.

"What's that?" Elizabeth leaned closer to the windshield, pointing to a dark shape that seemed to quiver behind the railings at the end of the upper porch. "Do you see it? There's something moving up there!"

"Probably just something blowing in the wind." Phillip followed her gaze. "One of those big black trash bags maybe—"

"No, I don't think so." Elizabeth frowned, struggling to make sense of the dark form that had moved now to lean against the wall of the old house. "It's a person. But what would anyone . . . I wish I could see—"

Phillip was already pulling out of the lot and toward the overgrown driveway that led up to the house. And even as he said "Something's not right here," the angular shape moved toward the porch railing. There was a flash of red and a tangle of rounded objects fell to the ground.

"It's a woman up there." Elizabeth craned her neck to get a better look at the figure high above them. "What's she doing . . . climbing up on something or . . . ?"

The question in her voice turned to horror. "Phillip! I think she's going to jump!"

The car was halfway up the driveway when they were halted by a downed tree lying across the overgrown ruts. High above them they could see the woman balanced on the railing. One arm around a porch pillar, she swayed in the wind.

Elizabeth shoved her door open and leaped from the car. Pulling on her jacket as she ran, she pounded up the steep drive, skidding treacherously on the frozen mud and ice-covered puddles. Behind her, she could hear the steady thud of Phillip's boots. Ahead she could see the scarecrow form of the woman, teetering on her precarious perch. Black hair writhed around her head, obscuring her face, and a long black coat lofted out in the wind, making her look like some great bird preparing for flight.

"Stop!" Elizabeth's voice was little more than a thin quaver against the wind, and she took a breath and tried again. "Please! . . . Wait! . . . Talk to us!"

This time her cry reached the woman on the railing, who turned at the sound. Her pale face stared at Elizabeth and her lips moved, but the words, if there were words, were carried away by the pitiless wind.

Elizabeth gasped. "Nola!"

She tried to run faster, even as she shouted to the figure high above her. "It's me, Nola—Elizabeth Goodweather. Please, get down from there before—"

The woman on the railing hesitated, wavered. Then she lifted her head as if listening to a faraway sound.

"Nola! Wait where you are, please! We'll help you . . ." Elizabeth's side was aching and her voice was a rasping croak, but she forced herself up the road and toward the old house. In the distance, a siren began its urgent howl.

Phillip was at her side now, pointing to the stairs that led to the upper porch. "Keep talking to her; I'll try to get up there."

The siren was louder now, very near.

"Nola, let us help you!" She kept moving toward the porch, laboring to be heard, to be understood, to get closer, to make eye contact with this woman she had met only a few months before. "Please, be careful; that railing looks—"

Above her the black-haired woman slowly shook her head. Elizabeth heard the emergency vehicle turn into the drive behind her. The siren shrieked once more, then died away.

She turned to see a Marshall County sheriff's car stopped just behind her jeep. Its light was pulsing in blue rhythmic bursts as two men, followed by a smaller figure in jeans and a purple fleece jacket, emerged from its interior and began to race up the drive.

Whirling to see what effect this new arrival would have, Elizabeth was just in time to see the black-clad figure release her hold on the post, spread her arms wide, and plunge—a great ungainly raven tumbling from the sky.

"How the hell she survived . . . if it hadn't been for one of those old boxwoods breaking her fall before she hit the stone walk . . ."

The EMTs had responded swiftly, strapping the crumpled, unconscious body of Miss Nola Barrett to a backboard and loading her into the ambulance for the trip to an Asheville emergency room. The young woman in the purple jacket had gone with Miss Barrett.

"She's the one who called us," Sheriff Mackenzie Blaine had explained. "Miss Barrett's niece or something—been visiting her aunt. She said Miss Barrett's started acting kind of squirrelly—obsessing about this house. Evidently the house belongs to Miss Barrett—or she thinks it does. Anyway, the niece—what's her name, Trace, Tracy?—said she went to the store after lunch and when she came back, her aunt was gone. She found footprints on the trail leading down this way and was concerned that Miss Barrett might be going to . . . to hurt herself."

Recenzii

“Regional mystery lovers, take note. A new heroine has come to town and her arrival is a time for rejoicing.” —Rapid River Magazine

“Vicki Lane shows us an exotic and colorful picture of Appalachia from an outsider's perspective—through a glass darkly.” —Sharyn McCrumb

“Lane is a master at creating authentic details while building suspense.” —Asheville Citizen-Times

“Vicki Lane shows us an exotic and colorful picture of Appalachia from an outsider's perspective—through a glass darkly.” —Sharyn McCrumb

“Lane is a master at creating authentic details while building suspense.” —Asheville Citizen-Times

Descriere

The author of "Art's Blood" returns with a complex, intricate novel of old family secrets and sudden revelations featuring heroine Elizabeth Goodweather of North Carolina's Full Circle Farm. Original.

Premii

- Anthony Awards Nominee, 2009