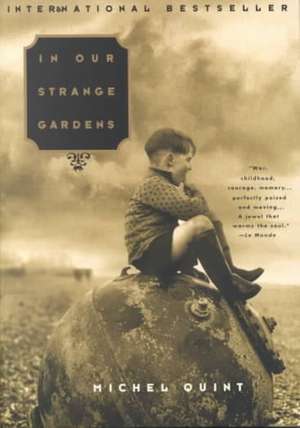

In Our Strange Gardens

Autor Michel Quinten Limba Engleză Paperback – dec 2001

In Our Strange Gardens was named a BookSense 76 Recommended Pick for January 2002! Michel has a story to tell. It's about his father, an exquisitely common man whose very ordinariness is a source of grave embarrassment for the boy. It's also the story told to him by his uncle, who shared a family secret with the child in the flickering black and white images of a Sunday matinee.

Years before, in the bitter years of World War II, during the Nazi occupation of France, two brothers found themselves at the mercy of a German guard following an explosive act of resistance. Thrown into a deep pit with a small group of terrified prisoners, the men are told that one of them will die by dawn to serve as an example for the others. It's up to the prisoners to propose who will be sacrificed. But in the middle of the night, the guard returns with an extraordinary proposition of his own.

A novel of revelation, innocence and ignorance, of the power of language and the strength and complexity of family, In Our Strange Gardens is a fable of nuance and power, a mesmerizing addition to the literature of war.

Years before, in the bitter years of World War II, during the Nazi occupation of France, two brothers found themselves at the mercy of a German guard following an explosive act of resistance. Thrown into a deep pit with a small group of terrified prisoners, the men are told that one of them will die by dawn to serve as an example for the others. It's up to the prisoners to propose who will be sacrificed. But in the middle of the night, the guard returns with an extraordinary proposition of his own.

A novel of revelation, innocence and ignorance, of the power of language and the strength and complexity of family, In Our Strange Gardens is a fable of nuance and power, a mesmerizing addition to the literature of war.

Preț: 119.22 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.81€ • 23.54$ • 19.04£

22.81€ • 23.54$ • 19.04£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 06-20 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781573229166

ISBN-10: 1573229164

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

ISBN-10: 1573229164

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Recenzii

"This brief but bittersweet novel...left a lump in my throat." —Baltimore Sun

"I doubt that there's a reader who, after rocketing through this mesmerizing miniature of large implication, will not go back immediately to read it again." —The New York Times

“Given the events of the last two months, Quint’s…parable about the often transitory and unpredictable nature of good and evil in wartime situations seems especially poignant and compelling…Readers won’t forget it.” —Publishers Weekly

"War, childhood, courage, memory...perfectly poised and moving...A jewel that warms the soul."—Le Monde (France)

"A little gem of a book, tender and funny, that breaks your heart. Unforgettable."—L'Express (France)

“The apparent simplicity of the writing…is deceptive—its density, its fusion of humour and tragedy, its economy of courage and farce, is the mark of a master.” —The Times (London)

“Magnificent.” —Elle (Italy)

“This book is admirable. A thousand times over… For the way it captures trials of conscience, about-turns, twists of fate. And what an ending.” —Journal du Dimanche

“A colorful, funny, poignant fable. Quint speaks of happiness, loyalty, friendship, he captures the humanity of characters whose dignity comes from their sense of what is right, from their humanity, their generosity. Give this to your loved ones, young and old, quickly” —Télérama

"I doubt that there's a reader who, after rocketing through this mesmerizing miniature of large implication, will not go back immediately to read it again." —The New York Times

“Given the events of the last two months, Quint’s…parable about the often transitory and unpredictable nature of good and evil in wartime situations seems especially poignant and compelling…Readers won’t forget it.” —Publishers Weekly

"War, childhood, courage, memory...perfectly poised and moving...A jewel that warms the soul."—Le Monde (France)

"A little gem of a book, tender and funny, that breaks your heart. Unforgettable."—L'Express (France)

“The apparent simplicity of the writing…is deceptive—its density, its fusion of humour and tragedy, its economy of courage and farce, is the mark of a master.” —The Times (London)

“Magnificent.” —Elle (Italy)

“This book is admirable. A thousand times over… For the way it captures trials of conscience, about-turns, twists of fate. And what an ending.” —Journal du Dimanche

“A colorful, funny, poignant fable. Quint speaks of happiness, loyalty, friendship, he captures the humanity of characters whose dignity comes from their sense of what is right, from their humanity, their generosity. Give this to your loved ones, young and old, quickly” —Télérama

Notă biografică

Michel Quint was born in France in 1949. He wrote for the theatre and for radio, before turning to thriller writing. In 1989 Quint was awarded the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière for his novel Billard à l’étage. In Our Strange Gardens is based on his own father’s life.

Extras

It was the end of ’42, beginning of ’43. Your father and I, through our small group of Resistance fighters, had been ordered to blow up all the generators in our district, starting with the one at Douai railway station. I never even understood why . . . He started his little story very mildly, my Gaston. Every so often, with a sort of naive nostalgia, his eyes would wander away from me to the old posters on the wall behind the bar—to the cowboys and their marvelous wildness, to the wickedly low-cut gowns of the ladies. Burt Lancaster, Virginia Mayo, Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, and their pals, all of them heroes, stars to drool over. Which is what I did, together with the more-on-the-ball of my friends. But from that day on, in comparison with Gaston, my father, and Nicole, too, these stars were nothing to me. Just pale mirages.

Outside it was sunny. But Gaston was talking of a time when darkness was strongest. And now he was coming to the point:

The last traces of winter. As it is in these parts. Damp, cold, rainy, and not much light. And on top of that, the war, the bereavements, the restrictions, and the feeling that humiliation was here to stay. But don’t get me wrong—although people were pretty fed up, they did their best not to knuckle under. That included us. I mean, we joined the Resistance. I don’t know about anybody else, but your father and I did it for a lark, just for something to do, that’s how it was at first at any rate . . . The same way we might have gone to a dance. But what with the atmosphere, the “Horst Wessel Song,” the military bands, we didn’t feel much like dancing. So we sabotaged the generator at Douai station, your father and I, to make some music of our own. A few touches on the right keys and bingo, a little night music. One evening just after dark. Without worrying much about it, without taking precautions. Just wearing the leather jackets electricians wear and carrying toolbags full of explosives. That seemed to us the best camouflage. We didn’t really think.

Wham! We were melting back into the landscape through the back roads when we heard the explosion behind us. We said the usual things: just like fireworks, and so on. Right, we said, we did it! And we went home and had a good night’s sleep. Didn’t even catch a cold!

For a while we thought we’d gotten away with it, as often happens, just because we hadn’t taken any precautions. Like with the lottery: you only hit the jackpot when you don’t care if you win or lose. See what I mean?

Anyhow, we hit the jackpot twice over that time! Once on the evening when we didn’t get caught, and then later on . . .

We were picked up the next morning down in the cellar. The cellar belonging to your grandparents, your mother’s father and mother. Among all the jars of jam and gherkins. A real treasure trove. You can laugh, but the Jerries knew what they were doing: a man caught in a secret lair with his arms full of luxury goods—well, he was bound to be dangerous. It was one of the ironies of fate, because even though, as I was telling you, we had blown up the generator, in order to look innocent we weren’t making any attempt to hide. I was helping your father put up some shelves to hold his future mother-in-law’s pickled vegetables. Then there they were—four Krauts jostling each other down the narrow staircase and laying into us. Before we had time to realize what was happening, they’d shoved us against the wall and cocked their guns, and André and I were bidding each other good-bye. Right away. No bravado. Forget heroics, forget using your last gasp to warble “The Marseillaise” into the enemy’s teeth—forget all that, my boy, it’s a fairy tale. In real life you don’t know where to look, what to grab to take with you into eternity, what to do with your hands, your eyes, your mouth. A woman’s face is best. But we didn’t have that. All we had was the gherkins. So, as they were taking aim at us and we could hear your grandmother screeching away upstairs, and our own hearts pounding down in the cellar, André and I just held hands. Like a couple of kids coming out of school, hanging on to each other so as not to have to walk home alone. With our eyes fixed on the jars of giant gherkins. Not the sort you pickle in vinegar—the sweet kind, done the Polish way, in brine. You can imagine the scene. We were just waiting for the shots, and for grim death. And then everything stopped.

There’s a clatter of boots on the stairs, a breathless NCO hurtles down hollering Achtung, Los, and Weg, and then a miracle happens and we’re not shot at all! Just a few good tickles with rifle butts and the odd kick to help us up the stairs. And it was only then that we were scared, at the thought that we might easily have been feeling nothing. It was being thumped that made us realize we were still alive!

Later on, after they’d marched us through the village, with our split lips and painful smiles, to show us off to the people skulking behind their shutters, and after a ride in a covered truck, lying facedown on the floor while our escorts wiped their boots on our ribs, we were taken before the Ober-whatsit at the Ortskommandantur, the local Germany army HQ. You know where that was? It was in the street where you were born, the rue Jean-Jaurès, and if you stand at the right distance—not too near and not too far—from the garden wall belonging to the big house there, you can still make out the word Ortskommandantur written up in white letters. The brick absorbed the paint, so it’s still there. Just as well. It acts as a reminder.

Yes, so they took us there. A few interviews, a slap or two, plenty of disparaging remarks, and finally they told us what the what-do-you-call-it was, the charge. That’s it, the charge. It came under the law of August 14, 1941. Which Pétain put through on the twenty-second, after Fabien killed a German naval cadet at the métro Barbès, but which was backdated to give the Maréchal legal cover for executing some hostages and placating the fellows in gray-green uniforms.

So what do you know? By virtue of the law of August 14 there we were, just like the guys in Paris on account of Fabien, being treated as hostages because the generator had gone up in smoke! I swear! If in three days’ time the people who’d done it hadn’t turned themselves in, we were going to take the fall. And this time for real!

You see the irony of it, don’t you, and the fix we were in? We couldn’t pin our hopes on someone confessing because we were the ones who did it, your father and I, and the dopey Huns had picked on us just by chance. Anyhow, whatever happened we were in for it. We’d either be shot as hostages, or as terrorists or anarchists or communists! Under the law of August 14.

Or perhaps they’d chosen us because we’d been stupid enough to boast about being in the Resistance, even if only in private, to impress a few of the guys. So the Jerries wanted to take care of us. But maybe they wanted us to confess to something else first, give them the names of some of our buddies—something like that. Or it could be a not-too-

obvious trick, to give themselves the chance to torture us and show the people who was in charge. But no, none of that made sense. No matter how much we stared at each other and turned it over in our heads, we couldn’t believe the Jerries would be that subtle. What we were really worried about was torture, being immersed in a bath or flogged. We weren’t sure we’d be able to hold out. But either they didn’t want to waste water or they didn’t take us seriously, because they stopped talking to us. We must have been left just standing there for a couple of hours or so in the conservatory, which was now the Oberboche’s office. Moving strictly verboten.

We practically took root.

Of course we know now we’d been picked out by the local French police. They were the ones who’d given the Krauts the list of prisoners. But you’ll never guess why they had it in for us . . .

Anyhow, at dusk we were back in the truck again. A long ten minutes bumping over roads even more battered than we were, and then they threw us down a clay pit, deep and round and with smooth, slippery sides. There on the edge of the Pas-de-Calais, at a place where clay used to be mined to supply a couple of factories—one that made bricks and another that made tiles. They were both disused, though, now. Your father said people used to put other people down ravines in the days of the Greeks and Romans.

It made a very easy and convenient prison. They didn’t even need to guard us. But it was cruel, too: sometimes the rain would just drizzle down in gusts, then it would pelt down good and hard, and there we were floundering about in a couple of inches of water. No getting away from it.

I could see the wet was going to seep inside our shoes and give us blisters and chilblains. If you tried to clamber up the side of the pit to where it was dry, you just slipped and fell back and got your ass plastered with clay in addition to freezing it stiff again. Not that it really mattered. To get us there, the Jerries had reversed the truck up to the edge of the pit, then prodded us in the back with the barrel of a gun, and we had fallen straight down into the mire. So we’d been covered in mud from the outset. No point in being fussy!

It was then, I remembered, that your father said something about grenades—or pomegranates; it’s the same word—and terrible gardens. I didn’t understand what he meant, and he didn’t explain.

Later on, when we were alone and our shoes were really sopping, we scraped up some clay and stamped it into a little ledge that we could perch on out of the wet. Anything more—trying to escape, cutting steps up the wall of the pit—was out of the question. The stuff just crumbled, slid away, sucked at the soles of your shoes; you could shape it well enough, but then it offered no foothold; you couldn’t count on it. And even if we’d managed to get to the top, we didn’t think the Jerries would just let us take off! They had guns up there, and it would have been child’s play to pick us off as we made a run for it.

So we just waited there in the drizzle with only our jackets to protect us. Shoulders hunched. Without speaking. The rain did clean us up, though. Once the blood was washed away, only the bruises were left.

—Reprinted from In Our Strange Gardens by Michel Quint by permission of Riverhead, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Translation from the French copyright © 2001 by Barbara Bray. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Outside it was sunny. But Gaston was talking of a time when darkness was strongest. And now he was coming to the point:

The last traces of winter. As it is in these parts. Damp, cold, rainy, and not much light. And on top of that, the war, the bereavements, the restrictions, and the feeling that humiliation was here to stay. But don’t get me wrong—although people were pretty fed up, they did their best not to knuckle under. That included us. I mean, we joined the Resistance. I don’t know about anybody else, but your father and I did it for a lark, just for something to do, that’s how it was at first at any rate . . . The same way we might have gone to a dance. But what with the atmosphere, the “Horst Wessel Song,” the military bands, we didn’t feel much like dancing. So we sabotaged the generator at Douai station, your father and I, to make some music of our own. A few touches on the right keys and bingo, a little night music. One evening just after dark. Without worrying much about it, without taking precautions. Just wearing the leather jackets electricians wear and carrying toolbags full of explosives. That seemed to us the best camouflage. We didn’t really think.

Wham! We were melting back into the landscape through the back roads when we heard the explosion behind us. We said the usual things: just like fireworks, and so on. Right, we said, we did it! And we went home and had a good night’s sleep. Didn’t even catch a cold!

For a while we thought we’d gotten away with it, as often happens, just because we hadn’t taken any precautions. Like with the lottery: you only hit the jackpot when you don’t care if you win or lose. See what I mean?

Anyhow, we hit the jackpot twice over that time! Once on the evening when we didn’t get caught, and then later on . . .

We were picked up the next morning down in the cellar. The cellar belonging to your grandparents, your mother’s father and mother. Among all the jars of jam and gherkins. A real treasure trove. You can laugh, but the Jerries knew what they were doing: a man caught in a secret lair with his arms full of luxury goods—well, he was bound to be dangerous. It was one of the ironies of fate, because even though, as I was telling you, we had blown up the generator, in order to look innocent we weren’t making any attempt to hide. I was helping your father put up some shelves to hold his future mother-in-law’s pickled vegetables. Then there they were—four Krauts jostling each other down the narrow staircase and laying into us. Before we had time to realize what was happening, they’d shoved us against the wall and cocked their guns, and André and I were bidding each other good-bye. Right away. No bravado. Forget heroics, forget using your last gasp to warble “The Marseillaise” into the enemy’s teeth—forget all that, my boy, it’s a fairy tale. In real life you don’t know where to look, what to grab to take with you into eternity, what to do with your hands, your eyes, your mouth. A woman’s face is best. But we didn’t have that. All we had was the gherkins. So, as they were taking aim at us and we could hear your grandmother screeching away upstairs, and our own hearts pounding down in the cellar, André and I just held hands. Like a couple of kids coming out of school, hanging on to each other so as not to have to walk home alone. With our eyes fixed on the jars of giant gherkins. Not the sort you pickle in vinegar—the sweet kind, done the Polish way, in brine. You can imagine the scene. We were just waiting for the shots, and for grim death. And then everything stopped.

There’s a clatter of boots on the stairs, a breathless NCO hurtles down hollering Achtung, Los, and Weg, and then a miracle happens and we’re not shot at all! Just a few good tickles with rifle butts and the odd kick to help us up the stairs. And it was only then that we were scared, at the thought that we might easily have been feeling nothing. It was being thumped that made us realize we were still alive!

Later on, after they’d marched us through the village, with our split lips and painful smiles, to show us off to the people skulking behind their shutters, and after a ride in a covered truck, lying facedown on the floor while our escorts wiped their boots on our ribs, we were taken before the Ober-whatsit at the Ortskommandantur, the local Germany army HQ. You know where that was? It was in the street where you were born, the rue Jean-Jaurès, and if you stand at the right distance—not too near and not too far—from the garden wall belonging to the big house there, you can still make out the word Ortskommandantur written up in white letters. The brick absorbed the paint, so it’s still there. Just as well. It acts as a reminder.

Yes, so they took us there. A few interviews, a slap or two, plenty of disparaging remarks, and finally they told us what the what-do-you-call-it was, the charge. That’s it, the charge. It came under the law of August 14, 1941. Which Pétain put through on the twenty-second, after Fabien killed a German naval cadet at the métro Barbès, but which was backdated to give the Maréchal legal cover for executing some hostages and placating the fellows in gray-green uniforms.

So what do you know? By virtue of the law of August 14 there we were, just like the guys in Paris on account of Fabien, being treated as hostages because the generator had gone up in smoke! I swear! If in three days’ time the people who’d done it hadn’t turned themselves in, we were going to take the fall. And this time for real!

You see the irony of it, don’t you, and the fix we were in? We couldn’t pin our hopes on someone confessing because we were the ones who did it, your father and I, and the dopey Huns had picked on us just by chance. Anyhow, whatever happened we were in for it. We’d either be shot as hostages, or as terrorists or anarchists or communists! Under the law of August 14.

Or perhaps they’d chosen us because we’d been stupid enough to boast about being in the Resistance, even if only in private, to impress a few of the guys. So the Jerries wanted to take care of us. But maybe they wanted us to confess to something else first, give them the names of some of our buddies—something like that. Or it could be a not-too-

obvious trick, to give themselves the chance to torture us and show the people who was in charge. But no, none of that made sense. No matter how much we stared at each other and turned it over in our heads, we couldn’t believe the Jerries would be that subtle. What we were really worried about was torture, being immersed in a bath or flogged. We weren’t sure we’d be able to hold out. But either they didn’t want to waste water or they didn’t take us seriously, because they stopped talking to us. We must have been left just standing there for a couple of hours or so in the conservatory, which was now the Oberboche’s office. Moving strictly verboten.

We practically took root.

Of course we know now we’d been picked out by the local French police. They were the ones who’d given the Krauts the list of prisoners. But you’ll never guess why they had it in for us . . .

Anyhow, at dusk we were back in the truck again. A long ten minutes bumping over roads even more battered than we were, and then they threw us down a clay pit, deep and round and with smooth, slippery sides. There on the edge of the Pas-de-Calais, at a place where clay used to be mined to supply a couple of factories—one that made bricks and another that made tiles. They were both disused, though, now. Your father said people used to put other people down ravines in the days of the Greeks and Romans.

It made a very easy and convenient prison. They didn’t even need to guard us. But it was cruel, too: sometimes the rain would just drizzle down in gusts, then it would pelt down good and hard, and there we were floundering about in a couple of inches of water. No getting away from it.

I could see the wet was going to seep inside our shoes and give us blisters and chilblains. If you tried to clamber up the side of the pit to where it was dry, you just slipped and fell back and got your ass plastered with clay in addition to freezing it stiff again. Not that it really mattered. To get us there, the Jerries had reversed the truck up to the edge of the pit, then prodded us in the back with the barrel of a gun, and we had fallen straight down into the mire. So we’d been covered in mud from the outset. No point in being fussy!

It was then, I remembered, that your father said something about grenades—or pomegranates; it’s the same word—and terrible gardens. I didn’t understand what he meant, and he didn’t explain.

Later on, when we were alone and our shoes were really sopping, we scraped up some clay and stamped it into a little ledge that we could perch on out of the wet. Anything more—trying to escape, cutting steps up the wall of the pit—was out of the question. The stuff just crumbled, slid away, sucked at the soles of your shoes; you could shape it well enough, but then it offered no foothold; you couldn’t count on it. And even if we’d managed to get to the top, we didn’t think the Jerries would just let us take off! They had guns up there, and it would have been child’s play to pick us off as we made a run for it.

So we just waited there in the drizzle with only our jackets to protect us. Shoulders hunched. Without speaking. The rain did clean us up, though. Once the blood was washed away, only the bruises were left.

—Reprinted from In Our Strange Gardens by Michel Quint by permission of Riverhead, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Translation from the French copyright © 2001 by Barbara Bray. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.