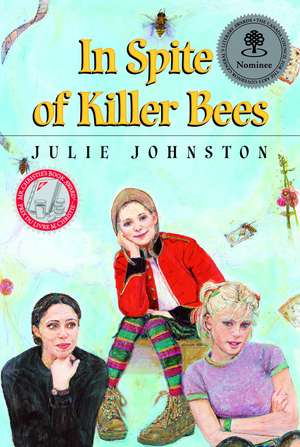

In Spite of Killer Bees

Autor Julie Johnstonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2002 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Rhode Island Teen Book Award (2004)

In the small, judgmental village, Aggie must fight to keep her diminishing family together. By refusing to abandon those she loves and comes to love, she risks more than her happiness.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 58.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 87

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.16€ • 11.61$ • 9.21£

11.16€ • 11.61$ • 9.21£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780887766015

ISBN-10: 0887766013

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 135 x 194 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

ISBN-10: 0887766013

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 135 x 194 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

Notă biografică

Born and raised in Smiths Falls, in the Ottawa Valley, Julie Johnston began writing plays in high school for her classmates. Her first published work was a short novel, which was published in serial form in the local paper. She returned to creating plays in the 1970s and this time focused on younger audiences, writing works her own children could perform. At the same time, she decided to try her hand at something more serious and entered a one-act composition in the Canadian Playwriting Competition, taking first prize.

A dexterous author who is comfortable writing drama, short stories and novels, she has garnered great success with her first two young adult novels, Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me and Hero of Lesser Causes, both of which won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Text in Children’s Literature and received numerous awards and accolades throughout North America.

In her long-awaited third novel, The Only Outcast, Julie takes readers back to the turn-of-the-century and into a summer of mystery, adventure and passion for sixteen-year-old Frederick at a summer cottage on the Rideau. The book was a finalist for the 1998 Governor General’s Literary Award and the Ruth Schwartz Children’s Book Award.

For Love Ya Like A Sister, Julie acted as editor, compiling the letters, journals, and e-mail correspondence of Katie Ouriou, a Calgary teen who died suddenly while living in Paris with her family. Katie’s messages to her friends back home in Canada are full of love, spiritual inspiration and demonstrate the strength that exists in the bonds of friendship.

In Spite of Killer Beesexamines the bonds between three sisters and their eclectic extended family in a small town.

The mother of four grown daughters, Julie Johnston and her husband reside in Peterborough.

From the Hardcover edition.

A dexterous author who is comfortable writing drama, short stories and novels, she has garnered great success with her first two young adult novels, Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me and Hero of Lesser Causes, both of which won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Text in Children’s Literature and received numerous awards and accolades throughout North America.

In her long-awaited third novel, The Only Outcast, Julie takes readers back to the turn-of-the-century and into a summer of mystery, adventure and passion for sixteen-year-old Frederick at a summer cottage on the Rideau. The book was a finalist for the 1998 Governor General’s Literary Award and the Ruth Schwartz Children’s Book Award.

For Love Ya Like A Sister, Julie acted as editor, compiling the letters, journals, and e-mail correspondence of Katie Ouriou, a Calgary teen who died suddenly while living in Paris with her family. Katie’s messages to her friends back home in Canada are full of love, spiritual inspiration and demonstrate the strength that exists in the bonds of friendship.

In Spite of Killer Beesexamines the bonds between three sisters and their eclectic extended family in a small town.

The mother of four grown daughters, Julie Johnston and her husband reside in Peterborough.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Looking out, Agatha says, “This could be in a movie.” Helen and Jeannie ignore her. They usually do, even though she’s fourteen now and believes she’s becoming quite interesting. Agatha has never told anyone this (someday she will), but she sometimes thinks she is both in a movie and watching it. She has the feeling that sometimes she soars.

Helen paid for the car, but Jeannie’s driving it. She’s seventeen, so why not? Of course, to call it a car, Aggie thinks, is flattering the thing – the two hundred and fifty dollar bag of scrap metal on wheels. It groans up the last hill. Agatha leans over the back of the front seat. For a moment all three sisters are breathless as they take in the panorama. “It’s the edge of the world,” Helen says. And so it seems for the fraction of a second they are perched there, the rest of their lives spread before them. Straight ahead, below, is the lake – bluer than the sky, flecked with diamonds in the glancing sun. Off to the right nestles the village of Port Desire.

The car releases a series of relieved backfires as it starts down the other side of the hill. They can see more of the village now: a church spire dazzling, haloed in the westerly sun. Around it, roofs of houses huddle like toadstools beneath tamed forests of trees.

The highway leads right into town to become the main street, LAKE STREET, a sign says. It’s lined with parked cars and on the sidewalks dozens of people in shorts and sunglasses amble along, eating ice cream cones, gazing into store windows. They cross the street wherever they feel like it, especially right in front of the Quade girls’ vehicle. Jeannie slams on the brakes more than once, muttering hostile names through her open window until Helen tells her not to be any more appalling than she has to be.

Agatha has been on the lookout for cops ever since they left Sudbury for the simple reason that Jeannie has only a G-1. Jeannie said, when they set off, “Don’t worry about it. It’s okay as long as you have an adult with you.” At twenty-two Helen counts as an adult, which is fine except that Helen doesn’t have a license, either. Agatha has felt rattled for nine solid hours, with Helen in the navigator’s seat telling Jeannie she’s getting too close to the shoulder, telling her to stay in her lane, telling her to shut her filthy mouth whenever Jeannie’s replies get a little too crass for Helen’s hoity-toity ears. Agatha isn’t used to her older sisters being quite so hostile. Back home in Sudbury, they pretty well ignore each other. She’s surprised they’ve all survived the trip without resorting to homicide.

Agatha (Aggie is what she prefers) has eyes like fringed chocolate pies. She has her head out, ogling the sights, memorizing the sounds. She can smell the lake, or maybe it’s the shore – hot sun on seaweed and wooden wharfs, with a hint of boat gas thrown in. The people here all look so nice and relaxed, some are even smiling. Slam go the brakes again as a jaywalking girl dripping ice cream jumps back out of the way of the car. “Oops!” says the girl, grinning. “Sorry.”

Aggie grins back through her open window and thinks she’d like to be able to phone up that girl and tell her everything that happens and laugh for an hour. She’s never actually done that with anyone. At her school in Sudbury, kids aren’t particularly friendly. They have names for her – Baggie, or Shaggie, which she ignores, and sometimes Ditz, which doesn’t even rhyme. Plus, she has to help in the deli after school, which doesn’t leave much time for friends. Aggie senses the girl staring at her shaved head, but doesn’t care. Something she had to do once in her life.

The Quade girls follow Lake Street as it curves past houses, a gas station, a store, a pharmacy, with little glimpses of the lake in between, boats on it zipping this way and that cresting the waves.

“Doesn’t this look like something out of a movie?” Aggie repeats.

“Not much,” Jeannie says.

“Start looking for house numbers,” Helen says.

On the other side of the street Aggie peers at a hardware store, a grocery store, and a stone castle that turns out to be the post office. Glancing back to the water side, across the street from the post office, she finds number 32. “So this was Grandfather Quade’s house!” Jeannie stops the car and they all bend their necks to get a good look.

“Could sure use a coat of paint,” Helen says.

Jeannie says, “It’s a dump.”

“No, it isn’t,” Aggie says. “Predump, maybe. There’s hope.”

Aggie cranes her neck and takes it all in. It’s tall, it’s wide, it’s redbrick with crooked, weather-beaten shutters framing fly-specked windows. Hollyhocks sway lazily at the side, and a rickety veranda in need of paint sags in front. It’s a monster of a place and smack on the main street.

Jeannie puts the car in gear, pulls into a grassed-over driveway on the far side of the house, and follows it around to the back, where the car promptly dies in front of a padlocked garage. They get out with their knapsacks, slam the car doors, and all three turn to make sure the impact hasn’t dismantled the car’s jigsaw puzzle chassis.

The house is closed tight, blinds down, curtains pulled. No point in knocking because who would answer? Helen has a door key sent by their grandfather’s lawyer with his letter. First time they’d ever got anything by courier, which made them all feel important. They are important. Not very many people in Sudbury have a millionaire grandfather die and leave them a huge fortune, at least no one they know. They go around to the front, but the key doesn’t work in the door.

“Wiggle it,” Jeannie says.

“It’s the wrong key,” Helen says.

Looking for another door, and carrying their knapsacks for fear they might be stolen, they retrace their steps around past the car to the back of the house. Stone steps lead down to a low door cut into the foundation. Helen can tell by looking at the large keyhole that their key won’t fit. Behind the house, what should be a back lawn is more like a hay field sprinkled with lacy white flowers they’ve never seen before, or noticed. It goes right down to the water’s edge to a lopsided building, its eaves scalloped and scrolled with the same trim as the house – a boathouse. Aggie lopes down for a closer look and pushes open the unlocked door. She calls, “Come and see it!” Her sisters meander down, Jeannie practically dead on her feet, Helen frowning over the key.

Inside, in the boat slip, in the muted light coming through the cobwebby windows, they make out an old wooden rowboat, its oars resting on the seats.

“I’d like to jump right in and go for a little row,” Aggie says.

“Underwater?” Jeannie says. “Better get a diving suit.”

The boat has buckets of water in it. The older girls head back up to the house, Jeannie’s yellow hair tangling in the breeze, Helen’s swept back tightly, her dark head on an angle.

“You stay out of that boat, Aggie!” Helen turns and calls.

Aggie mutters one or two halfhearted insults. She hates when Helen sounds motherish, although she should be used to it. One of these days, she thinks, smiling. (One of these days is her motto. It means, ‘wait for the future, things are bound to get better.’ She always adds, ‘once Mom comes back.’)

Things are already looking up, she has to admit. With all the money they’re going to inherit, they’ll be able to go anywhere, do anything. Their mom will come home and help them buy a nice little house somewhere and fix it up cute and she’ll cook delicious dinners and they’ll sit around watching videos, funny ones, and laugh till they roll on the floor, or sometimes sad ones, and they’ll pass around the box of Kleenex. Once Mom comes back into the family, they’ll all start liking each other, she’s pretty sure.

Aggie thinks this is probably what it’s like to have a religion. You always have some kind of heaven to look forward to. Aggie is a born-again family-girl.

*

The funeral isn’t until tomorrow at two in the afternoon, according to the letter they got from the lawyer. They came a day early to get their bearings, Helen says; case the joint, Jeannie says; make plans for the future, Aggie thinks.

*

Back in Sudbury, when Mrs. Muntz passed The Globe and Mail across the breakfast table to them, they crowded in to read the death notice and the article about their grandfather. “…considered one of the wealthiest men in Canada fifty years ago,” it said, and went on to tell how famous he was for owning silver mines way back when he was young. Helen clipped the article and saved it because they were in it, too. “Survived by two sisters and three granddaughters,” it said. She pasted it into the scrapbook she’s making about their family along with the letter they got from their grandfather’s lawyer saying that they were among the beneficiaries. Under the newspaper clipping Helen wrote: “Dad always used to say, luck is like an hourglass. When it runs out you turn it over and, before you know it, it comes pouring back in.”

*

The key works in a side door almost hidden by the trumpet-shaped hollyhocks ”– pink and purple, clinging defiantly up and down a thicket of stocks. The girls let themselves into a dark passageway that is lit only at the far end by faded daylight filtered through dingy windows on either side of the front door. They stand still for a moment, chilly in the gloom, breathing the stale air. Huddling close, they creep toward the front of the house, past closed doors. An open one, they notice, leads into a vast kitchen, high-ceilinged, with crack-lines in the plaster. All the ceilings are high. Farther along, past closed sliding doors, Helen flicks a light switch. A staircase, its center covered by threadbare carpeting held in place with thin brass rods, sweeps up from the front hall. To the left and right of it are living rooms – one stiffly grand, awash with ornamental knickknacks; the other smaller, padded with overstuffed chairs and couches, faded and sagging.

Aggie whispers, “Not your typical rich-people’s mansion, is it?” Everything looks decayed and dusty, with dreary pictures on the walls of shipwrecks and sheep and waterfalls and more sheep. “Not exactly a fun palace.”

Jeannie shivers. “Who’d want to live here?”

Helen says, “What did you expect? Our grandfather was sick in a hospital, or some place, for a long time before he died. No one has lived here for years, probably.”

“Our grandfather,” Aggie says. “Funny how we’ve gone through our entire lives without any relatives and, now that we’ve finally got a grandfather, he turns out to be dead.”

Something makes them turn back toward the stairs, listening.

“What?” Aggie’s eyes are wide.

“Listen.” Helen frowns.

They hear the slow drip of a tap, a fly buzzing a window, a sigh in the floor under them – sounds of a tired house. They turn to head back along the passageway, but out of the corner of her eye Aggie thinks she sees a shadow move. She screams, making them all scream as they race to the side door, stumbling, bumping each other with their knapsacks to be the first out.

“What was that?” Jeannie says.

“This place is haunted!”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Aggie,” Helen says.

Nevertheless, Helen leads the way around to the back of the house, where their car is parked. They get in and Jeannie tries to start it. Wa-wa-wa! it wails halfheartedly. The car has no intention of going anywhere.

*

Aggie and Helen are walking back along Lake Street. They’re looking for a motel, or a house with a room to rent, or a place selling tents cheap. Anything. They’re not going inside that house again, ghosts or no ghosts. Jeannie’s still back there behind the house, in the car, her head lolled against the window, sound asleep, not locked in because the car’s locks don’t work.

They aren’t having any luck at all finding a place to stay. Helen looks hot in her black sweater, buttoned right to the neck. Aggie would like to suggest an ice cream cone, but Helen would just say no. Not as many people around now, not as many ice cream cones going down this close to supper time. Aggie’s hungry. They turn down a short street, pass a booth selling ice cream, and go over a high bridge spanning the water. On the other side is a long weathered wharf, with boats tied to both sides of it – mostly houseboats and cabin cruisers in a variety of shapes and sizes. They read the names: Mamma’s Mink, Syracuse, NY; Ma Rêve, Trois Rivières, Que.

“If we find an empty one,” Aggie whispers, “we can sneak in after dark and spend the night.”

“As if.”

A squat houseboat, square-ended, in need of paint, casts off from the wharf and, churning slowly through the ropey weeds, heads up the shore in the direction of Grandfather Quade’s boathouse. Aggie stares at the people on it, shielding her eyes from the sun. “Hey!” she says. “Hey, that looks like Mom! It is Mom!” She runs along the wharf nearly tripping over mooring lines. “Mom!” she yells. “Mom!”

Helen comes up beside her, trying to get her to calm down. People are staring. People having a five-o’clock beer on the afterdeck of their boat grin at the girls with shaded eyes. “That’s Mom out there!” Aggie yells at Helen, nearly in tears. The woman has slipped into the cabin out of sight. They can see the man at the wheel taking the boat up the lake, not in any hurry.

“Come on,” Aggie says, grabbing Helen’s arm and pulling her back along the wharf and over the bridge. “We can take that old rowboat out and head them off.”

“Don’t be a total idiot,” Helen says. Aggie is always seeing their mother – in crowds, in passing cars, buses. Helen jogs along beside her, though, just to get her to shut up. Up the street they pound, Aggie rounding the house ahead of Helen, heading to the car at the back. She yanks the door open and Jeannie screams in shock, grabbing the steering wheel for balance.

“Mom’s out there in a boat,” Aggie yells. “Come on, we’re going after her.” She runs down and disappears into the boathouse.

Helen is out of breath from running. “Go down and get her out of there, will you?” she asks Jeannie.

“Get her yourself,” Jeannie says, slumping against the back of the seat.

“She’s going to drown herself.”

“Good. Two funerals for the price of one.”

Helen heaves a big, worn-out, why-do-I-have-to-do-it-all sigh.

Jeannie sighs, too. “Okay, okay.” She rolls out of the car and faces Helen. “I’m out of here, you know, the minute I get my share of the money.”

“Well, that makes two of us, honey.”

By the time Jeannie enters the boathouse, Aggie has the boat untied. “Get in,” she says.

“We can’t swim.”

“We don’t need to swim, we have a boat.”

“That thing could tip.”

“It won’t tip.” Aggie is in the boat now, more than ankle-deep in water.

Jeannie scowls, tells her not to be a jerk.

Aggie snorts her disgust. They can hear the putt-putt of the houseboat’s engine.

Standing in the boat alone, gripping one of the oars, teetering, Aggie poles it out of the boat slip into the breeze. She sits down with her back to the pointy end and fits the oars into the oarlocks, not really knowing what she’s doing. Push or pull? she wonders. She gives a mighty push and the boat lurches, blunt end first, out into the lake. Push, lurch, push, lurch, the water in it sloshes forward and back, over her feet and legs.

The houseboat is in sight now, quite close, its wake wedging out behind. Aggie stands up and yells, “Hey, Mom! Mom!” She pulls an oar out of its lock and waves it awkwardly above her head at the passing boat. “It’s me, Aggie!” She can’t see the woman. The man steers the boat without even looking at her. She might as well be one of the swallows darting and flitting over the waves. She lowers the oar and stands there breathing in and out, shoulders drooping, rocking with the waves. The houseboat is heading up the lake. When its swells hit Aggie’s unstable rowboat broadside, it’s enough to send her toppling, thrashing, into the water.

Jeannie, openmouthed, crouches in the boathouse. Through the frame of the off-kilter boat slip door, she watches the lake swallow her sister. She’s paralyzed with panic. She doesn’t know what to do. Aggie’s head comes up, but Jeannie can’t reach her. Aggie gasps in air and chokes, her face distorted. “Grab the oar, grab the oar,” Jeannie believes she calls, but no sound comes out. Aggie goes under again and Jeannie moans aloud. Her stomach heaves.

Aggie’s eyes are open underwater. She sees nothing but brownish green and thinks it must be the color of drowning. She’s lost contact with her arms and legs. They flail and thrash with a will of their own. She only knows about her chest, burning; her lungs, bursting. Up, she thinks, air is up. Her foot touches something solid.

Aggie makes a strangled retching sound as her head and shoulders break the surface. She reaches for the oar angling out from the boat and wraps her arms around it, clinging, gulping air, her throat rasping noisily. She hacks out a cough and sneeze together, then a loud belch. Her head and neck are still above water, but her toes are on the muddy bottom. Now she can swear, and does.

Jeannie gets her voice working. “Are you all right?”

Aggie coughs again and croaks, “It’s not all that deep.” She stretches out an arm and pulls the floating oar closer to her.

“You could have drowned!” Jeannie’s screaming, now.

“A lot you’d care!” Aggie’s still coughing hard, but manages to choke out, “You didn’t even try to save me.” She plows through the shoulder-high water, dragging the boat – her shaved head glistening, her nose running.

“What was I supposed to do? I can’t swim either.”

“You could have thrown something to me.”

“Like what?”

“You could have called for help.”

Jeannie stomps out of the boathouse.

From the Hardcover edition.

Looking out, Agatha says, “This could be in a movie.” Helen and Jeannie ignore her. They usually do, even though she’s fourteen now and believes she’s becoming quite interesting. Agatha has never told anyone this (someday she will), but she sometimes thinks she is both in a movie and watching it. She has the feeling that sometimes she soars.

Helen paid for the car, but Jeannie’s driving it. She’s seventeen, so why not? Of course, to call it a car, Aggie thinks, is flattering the thing – the two hundred and fifty dollar bag of scrap metal on wheels. It groans up the last hill. Agatha leans over the back of the front seat. For a moment all three sisters are breathless as they take in the panorama. “It’s the edge of the world,” Helen says. And so it seems for the fraction of a second they are perched there, the rest of their lives spread before them. Straight ahead, below, is the lake – bluer than the sky, flecked with diamonds in the glancing sun. Off to the right nestles the village of Port Desire.

The car releases a series of relieved backfires as it starts down the other side of the hill. They can see more of the village now: a church spire dazzling, haloed in the westerly sun. Around it, roofs of houses huddle like toadstools beneath tamed forests of trees.

The highway leads right into town to become the main street, LAKE STREET, a sign says. It’s lined with parked cars and on the sidewalks dozens of people in shorts and sunglasses amble along, eating ice cream cones, gazing into store windows. They cross the street wherever they feel like it, especially right in front of the Quade girls’ vehicle. Jeannie slams on the brakes more than once, muttering hostile names through her open window until Helen tells her not to be any more appalling than she has to be.

Agatha has been on the lookout for cops ever since they left Sudbury for the simple reason that Jeannie has only a G-1. Jeannie said, when they set off, “Don’t worry about it. It’s okay as long as you have an adult with you.” At twenty-two Helen counts as an adult, which is fine except that Helen doesn’t have a license, either. Agatha has felt rattled for nine solid hours, with Helen in the navigator’s seat telling Jeannie she’s getting too close to the shoulder, telling her to stay in her lane, telling her to shut her filthy mouth whenever Jeannie’s replies get a little too crass for Helen’s hoity-toity ears. Agatha isn’t used to her older sisters being quite so hostile. Back home in Sudbury, they pretty well ignore each other. She’s surprised they’ve all survived the trip without resorting to homicide.

Agatha (Aggie is what she prefers) has eyes like fringed chocolate pies. She has her head out, ogling the sights, memorizing the sounds. She can smell the lake, or maybe it’s the shore – hot sun on seaweed and wooden wharfs, with a hint of boat gas thrown in. The people here all look so nice and relaxed, some are even smiling. Slam go the brakes again as a jaywalking girl dripping ice cream jumps back out of the way of the car. “Oops!” says the girl, grinning. “Sorry.”

Aggie grins back through her open window and thinks she’d like to be able to phone up that girl and tell her everything that happens and laugh for an hour. She’s never actually done that with anyone. At her school in Sudbury, kids aren’t particularly friendly. They have names for her – Baggie, or Shaggie, which she ignores, and sometimes Ditz, which doesn’t even rhyme. Plus, she has to help in the deli after school, which doesn’t leave much time for friends. Aggie senses the girl staring at her shaved head, but doesn’t care. Something she had to do once in her life.

The Quade girls follow Lake Street as it curves past houses, a gas station, a store, a pharmacy, with little glimpses of the lake in between, boats on it zipping this way and that cresting the waves.

“Doesn’t this look like something out of a movie?” Aggie repeats.

“Not much,” Jeannie says.

“Start looking for house numbers,” Helen says.

On the other side of the street Aggie peers at a hardware store, a grocery store, and a stone castle that turns out to be the post office. Glancing back to the water side, across the street from the post office, she finds number 32. “So this was Grandfather Quade’s house!” Jeannie stops the car and they all bend their necks to get a good look.

“Could sure use a coat of paint,” Helen says.

Jeannie says, “It’s a dump.”

“No, it isn’t,” Aggie says. “Predump, maybe. There’s hope.”

Aggie cranes her neck and takes it all in. It’s tall, it’s wide, it’s redbrick with crooked, weather-beaten shutters framing fly-specked windows. Hollyhocks sway lazily at the side, and a rickety veranda in need of paint sags in front. It’s a monster of a place and smack on the main street.

Jeannie puts the car in gear, pulls into a grassed-over driveway on the far side of the house, and follows it around to the back, where the car promptly dies in front of a padlocked garage. They get out with their knapsacks, slam the car doors, and all three turn to make sure the impact hasn’t dismantled the car’s jigsaw puzzle chassis.

The house is closed tight, blinds down, curtains pulled. No point in knocking because who would answer? Helen has a door key sent by their grandfather’s lawyer with his letter. First time they’d ever got anything by courier, which made them all feel important. They are important. Not very many people in Sudbury have a millionaire grandfather die and leave them a huge fortune, at least no one they know. They go around to the front, but the key doesn’t work in the door.

“Wiggle it,” Jeannie says.

“It’s the wrong key,” Helen says.

Looking for another door, and carrying their knapsacks for fear they might be stolen, they retrace their steps around past the car to the back of the house. Stone steps lead down to a low door cut into the foundation. Helen can tell by looking at the large keyhole that their key won’t fit. Behind the house, what should be a back lawn is more like a hay field sprinkled with lacy white flowers they’ve never seen before, or noticed. It goes right down to the water’s edge to a lopsided building, its eaves scalloped and scrolled with the same trim as the house – a boathouse. Aggie lopes down for a closer look and pushes open the unlocked door. She calls, “Come and see it!” Her sisters meander down, Jeannie practically dead on her feet, Helen frowning over the key.

Inside, in the boat slip, in the muted light coming through the cobwebby windows, they make out an old wooden rowboat, its oars resting on the seats.

“I’d like to jump right in and go for a little row,” Aggie says.

“Underwater?” Jeannie says. “Better get a diving suit.”

The boat has buckets of water in it. The older girls head back up to the house, Jeannie’s yellow hair tangling in the breeze, Helen’s swept back tightly, her dark head on an angle.

“You stay out of that boat, Aggie!” Helen turns and calls.

Aggie mutters one or two halfhearted insults. She hates when Helen sounds motherish, although she should be used to it. One of these days, she thinks, smiling. (One of these days is her motto. It means, ‘wait for the future, things are bound to get better.’ She always adds, ‘once Mom comes back.’)

Things are already looking up, she has to admit. With all the money they’re going to inherit, they’ll be able to go anywhere, do anything. Their mom will come home and help them buy a nice little house somewhere and fix it up cute and she’ll cook delicious dinners and they’ll sit around watching videos, funny ones, and laugh till they roll on the floor, or sometimes sad ones, and they’ll pass around the box of Kleenex. Once Mom comes back into the family, they’ll all start liking each other, she’s pretty sure.

Aggie thinks this is probably what it’s like to have a religion. You always have some kind of heaven to look forward to. Aggie is a born-again family-girl.

*

The funeral isn’t until tomorrow at two in the afternoon, according to the letter they got from the lawyer. They came a day early to get their bearings, Helen says; case the joint, Jeannie says; make plans for the future, Aggie thinks.

*

Back in Sudbury, when Mrs. Muntz passed The Globe and Mail across the breakfast table to them, they crowded in to read the death notice and the article about their grandfather. “…considered one of the wealthiest men in Canada fifty years ago,” it said, and went on to tell how famous he was for owning silver mines way back when he was young. Helen clipped the article and saved it because they were in it, too. “Survived by two sisters and three granddaughters,” it said. She pasted it into the scrapbook she’s making about their family along with the letter they got from their grandfather’s lawyer saying that they were among the beneficiaries. Under the newspaper clipping Helen wrote: “Dad always used to say, luck is like an hourglass. When it runs out you turn it over and, before you know it, it comes pouring back in.”

*

The key works in a side door almost hidden by the trumpet-shaped hollyhocks ”– pink and purple, clinging defiantly up and down a thicket of stocks. The girls let themselves into a dark passageway that is lit only at the far end by faded daylight filtered through dingy windows on either side of the front door. They stand still for a moment, chilly in the gloom, breathing the stale air. Huddling close, they creep toward the front of the house, past closed doors. An open one, they notice, leads into a vast kitchen, high-ceilinged, with crack-lines in the plaster. All the ceilings are high. Farther along, past closed sliding doors, Helen flicks a light switch. A staircase, its center covered by threadbare carpeting held in place with thin brass rods, sweeps up from the front hall. To the left and right of it are living rooms – one stiffly grand, awash with ornamental knickknacks; the other smaller, padded with overstuffed chairs and couches, faded and sagging.

Aggie whispers, “Not your typical rich-people’s mansion, is it?” Everything looks decayed and dusty, with dreary pictures on the walls of shipwrecks and sheep and waterfalls and more sheep. “Not exactly a fun palace.”

Jeannie shivers. “Who’d want to live here?”

Helen says, “What did you expect? Our grandfather was sick in a hospital, or some place, for a long time before he died. No one has lived here for years, probably.”

“Our grandfather,” Aggie says. “Funny how we’ve gone through our entire lives without any relatives and, now that we’ve finally got a grandfather, he turns out to be dead.”

Something makes them turn back toward the stairs, listening.

“What?” Aggie’s eyes are wide.

“Listen.” Helen frowns.

They hear the slow drip of a tap, a fly buzzing a window, a sigh in the floor under them – sounds of a tired house. They turn to head back along the passageway, but out of the corner of her eye Aggie thinks she sees a shadow move. She screams, making them all scream as they race to the side door, stumbling, bumping each other with their knapsacks to be the first out.

“What was that?” Jeannie says.

“This place is haunted!”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Aggie,” Helen says.

Nevertheless, Helen leads the way around to the back of the house, where their car is parked. They get in and Jeannie tries to start it. Wa-wa-wa! it wails halfheartedly. The car has no intention of going anywhere.

*

Aggie and Helen are walking back along Lake Street. They’re looking for a motel, or a house with a room to rent, or a place selling tents cheap. Anything. They’re not going inside that house again, ghosts or no ghosts. Jeannie’s still back there behind the house, in the car, her head lolled against the window, sound asleep, not locked in because the car’s locks don’t work.

They aren’t having any luck at all finding a place to stay. Helen looks hot in her black sweater, buttoned right to the neck. Aggie would like to suggest an ice cream cone, but Helen would just say no. Not as many people around now, not as many ice cream cones going down this close to supper time. Aggie’s hungry. They turn down a short street, pass a booth selling ice cream, and go over a high bridge spanning the water. On the other side is a long weathered wharf, with boats tied to both sides of it – mostly houseboats and cabin cruisers in a variety of shapes and sizes. They read the names: Mamma’s Mink, Syracuse, NY; Ma Rêve, Trois Rivières, Que.

“If we find an empty one,” Aggie whispers, “we can sneak in after dark and spend the night.”

“As if.”

A squat houseboat, square-ended, in need of paint, casts off from the wharf and, churning slowly through the ropey weeds, heads up the shore in the direction of Grandfather Quade’s boathouse. Aggie stares at the people on it, shielding her eyes from the sun. “Hey!” she says. “Hey, that looks like Mom! It is Mom!” She runs along the wharf nearly tripping over mooring lines. “Mom!” she yells. “Mom!”

Helen comes up beside her, trying to get her to calm down. People are staring. People having a five-o’clock beer on the afterdeck of their boat grin at the girls with shaded eyes. “That’s Mom out there!” Aggie yells at Helen, nearly in tears. The woman has slipped into the cabin out of sight. They can see the man at the wheel taking the boat up the lake, not in any hurry.

“Come on,” Aggie says, grabbing Helen’s arm and pulling her back along the wharf and over the bridge. “We can take that old rowboat out and head them off.”

“Don’t be a total idiot,” Helen says. Aggie is always seeing their mother – in crowds, in passing cars, buses. Helen jogs along beside her, though, just to get her to shut up. Up the street they pound, Aggie rounding the house ahead of Helen, heading to the car at the back. She yanks the door open and Jeannie screams in shock, grabbing the steering wheel for balance.

“Mom’s out there in a boat,” Aggie yells. “Come on, we’re going after her.” She runs down and disappears into the boathouse.

Helen is out of breath from running. “Go down and get her out of there, will you?” she asks Jeannie.

“Get her yourself,” Jeannie says, slumping against the back of the seat.

“She’s going to drown herself.”

“Good. Two funerals for the price of one.”

Helen heaves a big, worn-out, why-do-I-have-to-do-it-all sigh.

Jeannie sighs, too. “Okay, okay.” She rolls out of the car and faces Helen. “I’m out of here, you know, the minute I get my share of the money.”

“Well, that makes two of us, honey.”

By the time Jeannie enters the boathouse, Aggie has the boat untied. “Get in,” she says.

“We can’t swim.”

“We don’t need to swim, we have a boat.”

“That thing could tip.”

“It won’t tip.” Aggie is in the boat now, more than ankle-deep in water.

Jeannie scowls, tells her not to be a jerk.

Aggie snorts her disgust. They can hear the putt-putt of the houseboat’s engine.

Standing in the boat alone, gripping one of the oars, teetering, Aggie poles it out of the boat slip into the breeze. She sits down with her back to the pointy end and fits the oars into the oarlocks, not really knowing what she’s doing. Push or pull? she wonders. She gives a mighty push and the boat lurches, blunt end first, out into the lake. Push, lurch, push, lurch, the water in it sloshes forward and back, over her feet and legs.

The houseboat is in sight now, quite close, its wake wedging out behind. Aggie stands up and yells, “Hey, Mom! Mom!” She pulls an oar out of its lock and waves it awkwardly above her head at the passing boat. “It’s me, Aggie!” She can’t see the woman. The man steers the boat without even looking at her. She might as well be one of the swallows darting and flitting over the waves. She lowers the oar and stands there breathing in and out, shoulders drooping, rocking with the waves. The houseboat is heading up the lake. When its swells hit Aggie’s unstable rowboat broadside, it’s enough to send her toppling, thrashing, into the water.

Jeannie, openmouthed, crouches in the boathouse. Through the frame of the off-kilter boat slip door, she watches the lake swallow her sister. She’s paralyzed with panic. She doesn’t know what to do. Aggie’s head comes up, but Jeannie can’t reach her. Aggie gasps in air and chokes, her face distorted. “Grab the oar, grab the oar,” Jeannie believes she calls, but no sound comes out. Aggie goes under again and Jeannie moans aloud. Her stomach heaves.

Aggie’s eyes are open underwater. She sees nothing but brownish green and thinks it must be the color of drowning. She’s lost contact with her arms and legs. They flail and thrash with a will of their own. She only knows about her chest, burning; her lungs, bursting. Up, she thinks, air is up. Her foot touches something solid.

Aggie makes a strangled retching sound as her head and shoulders break the surface. She reaches for the oar angling out from the boat and wraps her arms around it, clinging, gulping air, her throat rasping noisily. She hacks out a cough and sneeze together, then a loud belch. Her head and neck are still above water, but her toes are on the muddy bottom. Now she can swear, and does.

Jeannie gets her voice working. “Are you all right?”

Aggie coughs again and croaks, “It’s not all that deep.” She stretches out an arm and pulls the floating oar closer to her.

“You could have drowned!” Jeannie’s screaming, now.

“A lot you’d care!” Aggie’s still coughing hard, but manages to choke out, “You didn’t even try to save me.” She plows through the shoulder-high water, dragging the boat – her shaved head glistening, her nose running.

“What was I supposed to do? I can’t swim either.”

“You could have thrown something to me.”

“Like what?”

“You could have called for help.”

Jeannie stomps out of the boathouse.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A gem – another one – from two–time Governor–General’s Award-winner Julie Johnston.”

–The Globe and Mail

“…a signature Julie Johnston story: complex, subtle, and engaging.”

–The Horn Book Magazine

“…Johnston’s…narrative is compelling, fluctuating between distance, edginess, and heartfelt intimacy…An insightful novel about sisters, reconciling past and present, and opening hearts and minds.”

–Booklist

“Forget killer bees. What this Canadian novel has is a killer plot.”

–Washington Post

“Julie Johnston is quickly becoming the Alice Munro of Canadian children’s publishing…[this is] a brilliant, brilliant book.”

–Michele Landsberg

“Extraordinary…Johnston has created an exuberant novel that simply whips readers into the midst of these unforgettable characters.”

–Quill & Quire

“This is a leisurely, intriguing, and offbeat saga about a ‘born-again family-girl’ who finds a place in the world.”

–The Bulletin

“Aggie is sure to become one of Johnston’s most beloved characters.”

–Children’s Book News Summer/Fall 2001

“Johnston’s novel is a delightful mixture of warmth and disfunctionality, alienation and human contact…Johnston has a hilarious penchant for undercutting sentiment…Here’s heart, readability and enormous literary sophistication, all lightly worn.”

–The Toronto Star

From the Hardcover edition.

–The Globe and Mail

“…a signature Julie Johnston story: complex, subtle, and engaging.”

–The Horn Book Magazine

“…Johnston’s…narrative is compelling, fluctuating between distance, edginess, and heartfelt intimacy…An insightful novel about sisters, reconciling past and present, and opening hearts and minds.”

–Booklist

“Forget killer bees. What this Canadian novel has is a killer plot.”

–Washington Post

“Julie Johnston is quickly becoming the Alice Munro of Canadian children’s publishing…[this is] a brilliant, brilliant book.”

–Michele Landsberg

“Extraordinary…Johnston has created an exuberant novel that simply whips readers into the midst of these unforgettable characters.”

–Quill & Quire

“This is a leisurely, intriguing, and offbeat saga about a ‘born-again family-girl’ who finds a place in the world.”

–The Bulletin

“Aggie is sure to become one of Johnston’s most beloved characters.”

–Children’s Book News Summer/Fall 2001

“Johnston’s novel is a delightful mixture of warmth and disfunctionality, alienation and human contact…Johnston has a hilarious penchant for undercutting sentiment…Here’s heart, readability and enormous literary sophistication, all lightly worn.”

–The Toronto Star

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Rhode Island Teen Book Award Nominee, 2004