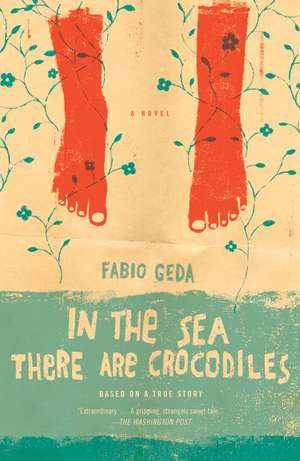

In the Sea There Are Crocodiles: Based on the True Story of Enaiatollah Akbari

Autor Fabio Geda Traducere de Howard Curtisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2012

In early 2002, Enaiatollah Akbari’s village fell prey to the Taliban. His mother, fearing for his life, led him across the border. So began Enaiat’s remarkable and often publishing five-year ordeal—trekking across bitterly cold mountains, riding the suffocating false bottom of a truck, steering an inflatable raft in violent waters—through Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, and Greece, before he eventually sought political asylum in Italy, all before he turned fifteen years old.

Here Fabio Geda delivers the moving true story of Enaiat’s extraordinary will to survive and of the accidental brotherhood he found with the boys he met along the way. In the Sea There Are Crocodiles brilliantly captures Enaiat’s engaging voice and humor, in what is a truly epic story of hope and survival, for readers of all ages.

Preț: 91.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 137

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.50€ • 18.03$ • 14.68£

17.50€ • 18.03$ • 14.68£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307743824

ISBN-10: 0307743829

Pagini: 214

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307743829

Pagini: 214

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Fabio Geda is an Italian novelist who works with children under duress. He writes for several Italian magazines and newspapers and teaches creative writing at Scuola Holden, the Italian school of storytelling in Turin. This is his first book to be translated into English.

Enaiatollah Akbari graduated from high school in the spring of 2011 and plans to attend university in Italy while continuing to support his mother and siblings, who are now living in Pakistan. He dreams of having the chance to return one day to a democratic and peaceful Afghanistan.

Enaiatollah Akbari graduated from high school in the spring of 2011 and plans to attend university in Italy while continuing to support his mother and siblings, who are now living in Pakistan. He dreams of having the chance to return one day to a democratic and peaceful Afghanistan.

Extras

AFGHANISTAN

The thing is, I really wasn’t expecting her to go. Because when you’re ten years old and getting ready for bed, on a night that’s just like any other night, no darker or starrier or more silent or more full of smells than usual, with the familiar sound of the muezzins calling the faithful to prayer from the tops of the minarets just like any- where else... no, when you’re ten years old—I say ten, although I’m not entirely sure when I was born, because there’s no registry office or anything like that in Ghazni province—like I said, when you’re ten years old, and your mother, before putting you to bed, takes your head and holds it against her breast for a long time, longer than usual, and says, There are three things you must never do in life, Enaiat jan, for any reason... The first is use drugs. Some of them taste good and smell good and they whisper in your ear that they’ll make you feel better than you could ever feel without them. Don’t believe them. Promise me you won’t do it.

I promise.

The second is use weapons. Even if someone hurts your feelings or damages your memories, or insults God, the earth or men, promise me you’ll never pick up a gun, or a knife, or a stone, or even the wooden ladle we use for making qhorma palaw, if that ladle can be used to hurt someone. Promise.

I promise.

The third is cheat or steal. What’s yours belongs to you, what isn’t doesn’t. You can earn the money you need by working, even if the work is hard. You must never cheat anyone, Enaiat jan, all right? You must be hospitable and tolerant to everyone. Promise me you’ll do that.

I promise.

Anyway, even when your mother says things like that and then, still stroking your neck, looks up at the window and starts talking about dreams, dreams like the moon, which at night is so bright you can see to eat by it, and about wishes—how you must always have a wish in front of your eyes, like a donkey with a carrot, and how it’s in trying to satisfy our wishes that we find the strength to pick ourselves up, and if you hold a wish up high, any wish, just in front of your forehead, then life will always be worth living—well, even when your mother, as she helps you get to sleep, says all these things in a strange, low voice as warming as embers, and fills the silence with words, this woman who’s always been so sharp, so quick- witted in dealing with life... even at a time like that, it doesn’t occur to you that what she’s really saying is, Khoda negahdar, goodbye.

Just like that.

When I opened my eyes in the morning, I had a good stretch to wake myself up, then reached over to my right, feeling for the comforting presence of my mother’s body. The reassuring smell of her skin always said to me, Wake up, get out of bed, come on...But my hand felt nothing, only the white cotton cover between my fingers. I pulled it toward me. I turned over, with my eyes wide open. I propped myself on my elbows and tried calling out, Mother. But she didn’t reply and no one replied in her place. She wasn’t on the mattress, she wasn’t in the room where we had slept, which was still warm with bodies tossing and turning in the half-light, she wasn’t in the doorway, she wasn’t at the window looking out at the street filled with cars and carts and bikes, she wasn’t next to the water jars or in the smokers’ corner talking to someone, as she had often been during those three days.

From outside came the din of Quetta, which is much, much noisier than my little village in Ghazni, that strip of land, houses and streams that I come from, the most beautiful place in the world (and I’m not just boasting, it’s true).

Little or big.

It didn’t occur to me that the reason for all that din might be because we were in a big city. I thought it was just one of the normal differences between countries, like different ways of seasoning meat. I thought the sound of Pakistan was simply different from the sound of Afghanistan, and that every country had its own sound, which depended on a whole lot of things, like what people ate and how they moved around.

Mother, I called.

No answer. So I got out from under the covers, put my shoes on, rubbed my eyes and went to find the owner of the place to ask if he’d seen her, because three days earlier, as soon as we arrived, he’d told us that no one went in or out without him noticing, which seemed odd to me, since I assumed that even he needed to sleep from time to time.

The sun cut the entrance of the samavat Qgazi in two. Samavat means “hotel.” In that part of the world, they actually call those places hotels, but they’re nothing like what you think of as a hotel, Fabio. The samavat Qgazi wasn’t so much a hotel as a warehouse for bodies and souls, a kind of left-luggage office you cram into and then wait to be packed up and sent off to Iran or Afghanistan or wherever, a place to make contact with people traffickers.

We had been in the samavat for three days, never going out, me playing among the cushions, Mother talking to groups of women with children, some with whole families, people she seemed to trust.

I remember that, all the time we were in Quetta, my mother kept her face and body bundled up inside a burqa. In our house in Nava, with my aunt or with her friends, she never wore a burqa. I didn’t even know she had one. The first time I saw her put it on, at the border, I asked her why and she said with a smile, It’s a game, Enaiat, come inside. She lifted a flap of the garment, and I slipped between her legs and under the blue fabric. It was like diving into a swimming pool, and I held my breath, even though I wasn’t swimming.

Covering my eyes with my hand because of the light, I walked up to the owner, kaka Rahim, and apologized for bothering him. I asked about my mother, if by any chance he’d seen her go out, because nobody went in or out without him noticing, right?

Recenzii

“Inspiring.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine

“Extraordinary. . . . A gripping, strangely sweet tale. . . . Reading of Akbari’s efforts to find a better life—alone and at an age when children in our country can’t even drive yet—will leave you shaken, but his resilient joy leavens the story. . . . The lovely rapport between Akbari and Geda comes across now and then when the journalist interrupts to prod him for more detail, gently reminding him just how extraordinary his experience is.”

—The Washington Post

“A remarkable story.”

—The Financial Times

“Chilling. . . . Beautiful. . . . Heart-warming”

—The Times (London)

“A riveting and fast read, one that dips into emotional and physical violence but surfaces in a splash of redemption and humanity and hope. Adult readers will be gripped by the tale, as will young adult readers.”

—Denver Post

“Remarkable. . . . Exquisitely rendered and completely free from pride or self-pity. This book will break your heart at the same time that it is lifting your spirit and opening your understanding to a very different kind of life in our very same world.”

—The Daily Herald (London)

“A page-turner that makes you care about its hero from the outset and willingly accompany him on his often perilous journey from Afghanistan to Italy. . . . Salutary and humane, In the Sea There Are Crocodiles, as its international bestseller status indicates, deserves to be read widely by young and older readers alike.”

—The Guardian (London)

“As the reader, you have to wonder what you were doing circa 2005, while Enaiat was traversing the mountains of Turkey. Geda’s frank, unembellished prose captures the voice of a brave boy who never loses hope—and who is lucky to be alive to tell his story.”

—The National

“A contemporary look at a world that Americans have become increasingly a part of and from the point of view of persons who usually have no voice. . . . Geda has done a fine job bringing Enaiat alive.”

—The Washington Independent Book Review

“It’s sobering and heart lifting to see the stoical determination and achievement of someone who makes our world look like paradise. This little gem, beautifully and unobtrusively translated, will raise tears of sorrow and joy.”

—The Independent (London)

“Undeniably eye-opening. . . . A small book with a big story to tell. . . . What makes In the Sea There Are Crocodiles so persuasive is the boy’s voice, beautifully captured by Geda.”

—BookPage

“A remarkable, heart-warming story of courage and endurance in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. . . . Truly inspirational”

—The Irish Examiner

“Hair-raising. . . . Unforgettable. . . . An eye-opening account of human endurance, of overcoming the most difficult obstacles—all for freedom and a better life.”

—Counterpunch

“An authentic, open and marvelous voice of youthful exuberance.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

“A moving and eye-opening chronicle of hardships no child should have to endure, mitigated by intermittent kindnesses.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“Every so often a book comes along that is an absolute gift to the world. This is one such book.”

—Laura Fitzgerald, author of Dreaming in English and Veil of Roses

“In direct and undecorated prose, Fabio Geda beautifully delivers the human experience of Enaiatollah, a ten-year-old Afghani boy, whose will for survival is more than remarkable. In the Sea There Are Crocodiles will make you laugh and cry, and it will also make you a better person. Everyone should read this book.”

—Marina Nemat, winner of the inaugural Human Dignity Award and author of Prisoner of Tehran

—O, The Oprah Magazine

“Extraordinary. . . . A gripping, strangely sweet tale. . . . Reading of Akbari’s efforts to find a better life—alone and at an age when children in our country can’t even drive yet—will leave you shaken, but his resilient joy leavens the story. . . . The lovely rapport between Akbari and Geda comes across now and then when the journalist interrupts to prod him for more detail, gently reminding him just how extraordinary his experience is.”

—The Washington Post

“A remarkable story.”

—The Financial Times

“Chilling. . . . Beautiful. . . . Heart-warming”

—The Times (London)

“A riveting and fast read, one that dips into emotional and physical violence but surfaces in a splash of redemption and humanity and hope. Adult readers will be gripped by the tale, as will young adult readers.”

—Denver Post

“Remarkable. . . . Exquisitely rendered and completely free from pride or self-pity. This book will break your heart at the same time that it is lifting your spirit and opening your understanding to a very different kind of life in our very same world.”

—The Daily Herald (London)

“A page-turner that makes you care about its hero from the outset and willingly accompany him on his often perilous journey from Afghanistan to Italy. . . . Salutary and humane, In the Sea There Are Crocodiles, as its international bestseller status indicates, deserves to be read widely by young and older readers alike.”

—The Guardian (London)

“As the reader, you have to wonder what you were doing circa 2005, while Enaiat was traversing the mountains of Turkey. Geda’s frank, unembellished prose captures the voice of a brave boy who never loses hope—and who is lucky to be alive to tell his story.”

—The National

“A contemporary look at a world that Americans have become increasingly a part of and from the point of view of persons who usually have no voice. . . . Geda has done a fine job bringing Enaiat alive.”

—The Washington Independent Book Review

“It’s sobering and heart lifting to see the stoical determination and achievement of someone who makes our world look like paradise. This little gem, beautifully and unobtrusively translated, will raise tears of sorrow and joy.”

—The Independent (London)

“Undeniably eye-opening. . . . A small book with a big story to tell. . . . What makes In the Sea There Are Crocodiles so persuasive is the boy’s voice, beautifully captured by Geda.”

—BookPage

“A remarkable, heart-warming story of courage and endurance in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. . . . Truly inspirational”

—The Irish Examiner

“Hair-raising. . . . Unforgettable. . . . An eye-opening account of human endurance, of overcoming the most difficult obstacles—all for freedom and a better life.”

—Counterpunch

“An authentic, open and marvelous voice of youthful exuberance.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

“A moving and eye-opening chronicle of hardships no child should have to endure, mitigated by intermittent kindnesses.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“Every so often a book comes along that is an absolute gift to the world. This is one such book.”

—Laura Fitzgerald, author of Dreaming in English and Veil of Roses

“In direct and undecorated prose, Fabio Geda beautifully delivers the human experience of Enaiatollah, a ten-year-old Afghani boy, whose will for survival is more than remarkable. In the Sea There Are Crocodiles will make you laugh and cry, and it will also make you a better person. Everyone should read this book.”

—Marina Nemat, winner of the inaugural Human Dignity Award and author of Prisoner of Tehran

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Ten-year-old Enaiatollah is left alone in Pakistan to fend for himself. In a book based on a true story, Italian novelist Fabio Geda describes Enaiatollah's remarkable five-year journey from Afghanistan to Italy where he finally managed to claim political asylum. His ordeal took him through Iran, Turkey and Greece, working on building sites in order to pay people-traffickers, and enduring the physical misery of border crossings squeezed into the false bottoms of lorries or trekking across inhospitable mountains. A series of almost implausible strokes of fortune enabled him to get to Turin, where he found help from an Italian family and met Fabio Geda. The result of their friendship is this unique book in which Enaiatollah's engaging, moving voice is brilliantly captured by Geda's subtle storytelling. In Geda's hands, Enaiatollah's journey becomes a universal story of stoicism in the face of fear, and the search for a place where life is liveable.

Ten-year-old Enaiatollah is left alone in Pakistan to fend for himself. In a book based on a true story, Italian novelist Fabio Geda describes Enaiatollah's remarkable five-year journey from Afghanistan to Italy where he finally managed to claim political asylum. His ordeal took him through Iran, Turkey and Greece, working on building sites in order to pay people-traffickers, and enduring the physical misery of border crossings squeezed into the false bottoms of lorries or trekking across inhospitable mountains. A series of almost implausible strokes of fortune enabled him to get to Turin, where he found help from an Italian family and met Fabio Geda. The result of their friendship is this unique book in which Enaiatollah's engaging, moving voice is brilliantly captured by Geda's subtle storytelling. In Geda's hands, Enaiatollah's journey becomes a universal story of stoicism in the face of fear, and the search for a place where life is liveable.