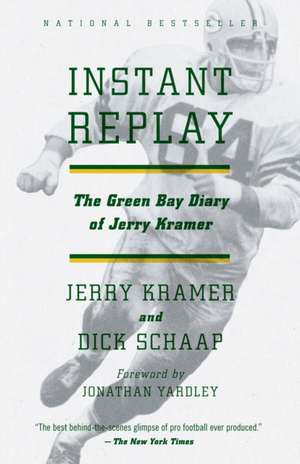

Instant Replay: The Green Bay Diary of Jerry Kramer

Autor Gerald L. Kramer, Dick Schaap, Jerry Krameren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2011

Candid and often amusing, Jerry Kramer describes from a player’s perspective a bygone era of sports, filled with blood, grit, and tears. No game better exemplifies this period than the classic “Ice Bowl” conference championship game between the Packers and the Dallas Cowboys, which Kramer, who made the crucial block in the climactic play, describes in thrilling detail. We also get a rare and insightful view of the Packers’ legendary leader, coach Vince Lombardi.

As vivid and engaging as it was when it was first published, Instant Replay is an irreplaceable reminder of the glory days of pro football.

Preț: 88.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 133

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.01€ • 17.87$ • 14.30£

17.01€ • 17.87$ • 14.30£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307743381

ISBN-10: 0307743381

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307743381

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Jerry Kramer was a right guard for the Green Bay Packers from 1958 to 1968. During his time with the team, the Packers won five National Championships and Super Bowls I and II. He was inducted into the Green Bay Packer Hall of Fame in 1977. He lives in Boise, Idaho.

Dick Schaap (1934–2002), a sportswriter, broadcaster, and author or coauthor of thirty-three books, reported for NBC Nightly News, the Today show, ABC World News Tonight, 20/20, and ESPN and was the recipient of five Emmy Awards.

Dick Schaap (1934–2002), a sportswriter, broadcaster, and author or coauthor of thirty-three books, reported for NBC Nightly News, the Today show, ABC World News Tonight, 20/20, and ESPN and was the recipient of five Emmy Awards.

Extras

1

PRELIMINARY SKIRMISHES

FEBRUARY 10

I drove downtown to the Packer offices today to pick up my mail, mostly fan mail about our victory in the first Super Bowl game, and as I came out of the building Coach Lombardi came in. I waved to him cheerfully--I have nothing against him during the off-season--and I said, "Hi, Coach."

Vince Lombardi is a short, stout man, a stump. He looked up at me and he started to speak and his jaws moved, but no words came out. He hung his head. My first thought--from force of habit, I guess--was I've done something wrong, I'm in trouble, he's mad at me. I just stood there and Lombardi started to speak again and again he opened his mouth and still he didn't say anything. I could see he was upset, really shaken.

"What is it, Coach?" I said. "What's the matter?"

Finally, he managed to say, "I had to put Paul--" He was almost stuttering. "I had to put Paul on that list," he said, "and they took him."

I didn't know what to say. I couldn't say anything. Vince had put Paul Hornung on the list of Packers eligible to be selected by the Saints, the new expansion team in New Orleans, and the Saints had taken him. Paul Hornung had been my teammate ever since I came to Green Bay in 1958, and he had been Vince's prize pupil ever since Vince came to Green Bay in 1959, and it may sound funny but I loved Paul and Vince loved Paul and everybody on the Packers loved Paul. From the stands, or on television, Paul may have looked cocky, with his goat shoulders and his blond hair and his strut, but to the people who knew him he was a beautiful guy.

I stood there, not saying anything, and Lombardi looked at me again and lowered his head and started to walk away. He took about four steps and then he turned around and said, "This is a helluva business sometimes, isn't it?"

Then he put his head down again and walked into his office.

I got to thinking about it later, and the man is a very emotional man. He is spurred to anger or to tears almost equally easily. He gets misty-eyed and he actually cries at times, and no one thinks less of him for crying. He's such a man.

JUNE 15

Practice starts a month from today, and I'm dreading it. I don't want to work that hard again. I don't want to take all that punishment again. I really don't know why I'm going to do it.

\I must get some enjoyment out of the game, though I can't say what it is. It isn't the body contact. Body contact may be fun for the defensive players, the ones who get to make the tackles, but body contact gives me only cuts and contusions, bruises and abrasions. I suppose I enjoy doing something well. I enjoy springing a back loose, making a good trap block, a good solid trap block, cutting down my man the way I'm supposed to. But I'm not quite as boyish about the whole thing as I used to be.

A couple of months ago, I was thinking seriously about retiring. Jimmy Taylor, who used to be my roommate on the Packers, and a couple of other fellows and I have a commercial diving business down in Louisiana. Jimmy, who comes from Baton Rouge and played for Louisiana State University, is a great asset to the business; he's such a hero in Louisiana I wouldn't be surprised if he ended up as governor. We've been building up the company for three years now, and this year, with Jimmy playing for the Saints--he played out his option here and jumped to New Orleans--we should really do well. He'll be able to entertain potential customers, wine them and dine them and take them to the Saints' games.

I thought of retiring so that I could devote more time to the company. And I would have retired, I believe, or at least tried to shift to the New Orleans team, if a deal hadn't come through with a man named Blaine Williams, who's in the advertising business in Green Bay. We're getting portraits made of all the players in the National Football League, and we're selling them to Kraft Foods to distribute on a nationwide basis. It can be a very lucrative thing for me, so I decided I'd better stay here in Green Bay and keep an eye on it.

Coach Lombardi heard that I was thinking about retiring--he hears everything--and he suspected I was going to use this as a wedge to demand more money. That wasn't what I had in mind, not this time.

Still, I haven't heard a word from Lombardi about a contract for this year.

JULY 5

Pat Peppler, the personnel director of the Packers, phoned today and asked me if I wanted to discuss my contract. I told him I wanted $27,500, up from $23,000 last year, and I said it isn't as much as I deserve, of course, but I'll be happy with it and I won't cause any problems, any struggle.

I mean it. I know I'm worth more than $27,500, but I don't want a contract fight over a few thousand dollars. I can remember what happened in 1963.

That was the year after I kicked three field goals in the world championship game against the New York Giants, and we won the game by three field goals, 16-7. During the 1962 season, I kicked extra points and field goals, and I was named All-Pro offensive guard, and, in general, I had a pretty good year. I came in wanting a sizable raise, and Coach Lombardi started out with the standard 10 percent he offers when he wants to give a guy a raise. I said I wanted nearly 50 percent, from $13,000 up to $19,000, and he hit the ceiling and said absolutely not. He said he'd give me $14,500 or maybe $15,000.

In the back of my mind, I was thinking about playing out my option--the one-year professional football contract allows a man to play out a second year at the same salary and then become a free agent, the way Jimmy Taylor did last year--and jumping to Denver in the rival American Football League. Denver wanted me badly.

Coach Lombardi, with his spy system, found out what I was thinking about. He has a real thing about loyalty, and he got doubly upset. He called me into his office and offered me $15,000 and said, "Look, I'm going to give you fifteen, but you have to take it today. Tomorrow, it'll be down to fourteen." I didn't take it.

I started training camp without a contract, and Vince made practice almost unbearable. Every block I threw, every move I made, was either slow or wrong or inadequate. "Move, Kramer, move," he'd scream, "you think you're worth so damn much." And the contract negotiations weren't kept at any executive level. They were held at lunch and dinner, at bedtime and during team meetings, and the rest of the coaches joined in, all of them on my back, sniping at me, taking potshots at me. I got bitter, I got jumpy, and then a lot of the other guys, my teammates, began to tease me, to ride me, and the teasing didn't sound like teasing to me because I was getting so much hell from all angles.

And then I almost exploded. We have a ritual the day before a game. The offensive linemen get together with the defensive linemen and throw passes to each other. We take turns playing quarterback, and you get to keep throwing passes until one of them is incomplete. It's a silly little game, but it loosens us up and it's fun. Every lineman's dream, of course, is to be a quarterback. So, in 1963, the day before an exhibition, we were playing this game, and I stepped up for my turn to play quarterback and Bill Austin, who was our line coach, yelled, "No, get out of there, Kramer, you can't be a quarterback."

I said, "Why not?"

And he said, "Just 'cause I said so."

There was no reason, except for the contract, and this burned me up. Later, Austin approached me in the lobby of the hotel we were staying in, and he said, "Jerry, I want to talk to you."

I said, "Look, you sonuvabitch, I don't want to talk to you at all. I don't have a word to say to you. I don't want to have anything to do with you. Stay away from me."

I was out of my head a little bit.

Bill said, "Now, now, don't be like that."

"I mean it, Bill," I said. "Stay away from me." I stopped just short of punching Austin.

That night, Coach Lombardi put me on the kickoff team, the suicide team, which is usually reserved, during exhibition games, for rookies. "The kickoff team is football's greatest test of courage," Lombardi says. "It's the way we find out who likes to hit."

I knew how dangerous the kickoff team could be. In 1961, when I was kicking off for the Packers, I had to be on the kickoff team, of course. I kicked off once against the Minnesota Vikings, the opening play of the game, and when I ran down the field, I ran straight at the wedge in front of the ballcarrier. The wedge is made up of four men, always four big and mobile men, more than 1,000 pounds' worth. One of the guys from the Minnesota wedge hit me in the chest and another scissored my legs and buckled me over backwards and then the ballcarrier stumbled onto me and pounded me into the ground and a couple of other guys ran over me and stomped me in deeper, and the result was a broken ankle. I missed eight games in 1961.

And then in 1963, for that exhibition, I found myself on the kickoff team again. I took out all my fury on the field. I was the first man down the field on every kickoff, I hit everyone who got in my way, and after the game Lombardi came up to me and said that he wasn't the vindictive type, that we could get together and settle the contract. I signed the next day for $17,500.

***

Pat Peppler told me today he would check with Coach Lombardi about my demand for $27,500.

JULY 7

Pat Peppler called back. "You can have $26,500," he said.

"If I wanted $26,500," I told him, "I would have asked for $26,500. If I'd said $44,500, I suppose Lombardi would have come back with $43,500. I want $27,500 without any fuss, without any argument."

JULY 10

"OK, it's $27,500," Pat Peppler said today. "Stop by and sign."

I'm going to forget that I ever thought about retiring. I'm going to forget that I've got a lot of money coming in. I'm going to forget that I don't really need football anymore.

I've decided to play. Let's get on with it.

2

BASIC TRAINING

JULY 14

Practice began officially yesterday for everyone except the veteran offensive and defensive linemen. We don't have to report until 6 p.m. tomorrow, Saturday, but I couldn't wait. I had to go over to the stadium this morning. It's not that I'm anxious to start the punishment, but I figured one workout today and one tomorrow would help me ease into training. Monday, we start two-a-days, which are pure hell, one workout in the morning and one in the afternoon, and if I don't get a little exercise, the two-a-days'll kill me.

Naturally, I saw Vince this morning. He asked me how I was, and, before I could tell him, he said, "You look a little heavy."

I guess I am. I was up around 265 a few weeks ago, and I'm 259 now, and I'd like to play somewhere between 245 and 250. I'm not too worried about my weight. I know I've got the best diet doctor in the world. His prize patient right now is a rookie tackle named Leon Crenshaw, from Tuskegee Institute, who reported to training camp a week ago weighing 315 pounds. Dr. Lombardi has reduced him to 302.

I started off the day by trotting three laps around the goal posts, a total of almost half a mile, not because I love running, but because Coach Lombardi insists upon this daily ritual. As long as he's been here, we've had only one fellow who didn't run his three laps, a big rookie named Royce Whittenton. When Green Bay drafted Whittenton during the winter of his senior year in college, he weighed about 240. When the coaches contacted him in the spring, he weighed 270. They told him they didn't want him to come to camp any heavier than 250, and he reported in the summer at 315 pounds. He made one lap and half of another around the goal posts and then he couldn't go any farther. Lombardi cut him from the squad before he even took calisthenics.

We had one of our little "nutcracker" drills today, a brand of torture--one on one, offensive man against defensive man--which is, I imagine, something like being in the pit. The defensive man positions himself between two huge bags filled with foam rubber, which form a chute; the offensive man, leading a ballcarrier, tries to drive the defensive man out of the chute, banging into him, head-to-head, really rattling each other, ramming each other's neck down into the chest.

The primary idea is to open a path for the ballcarrier. The secondary idea is to draw blood. I hate it. But Coach Lombardi seemed to enjoy watching every fresh collision.

Lombardi thinks of himself as the patriarch of a large family, and he loves all his children, and he worries about all of them, but he demands more of his gifted children. Lee Roy Caffey, a tough linebacker from Texas, is one of the gifted children, and Coach Lombardi is always on Lee Roy, chewing him, harassing him, cussing him. We call Lee Roy "Big Turkey," as in, "You ought to be ashamed of yourself, you big turkey," a Lombardi line. Vince kept saying during the drill today that if anyone wanted to look like an All-American, he should just step in against Caffey.

"Look at yourself, Caffey, look at yourself, that stinks," Lombardi shouted. Later, Vince added, "Lee Roy, you may think that I criticize you too much, a little unduly at times, but you have the size, the strength, the speed, the mobility, everything in the world necessary to be a great football player, except one thing: YOU'RE TOO DAMN LAZY."

During the nutcracker, Red Mack, a reserve flanker for us last year who weighs 179 pounds soaking wet, lined up against Ray Nitschke, who weighs 240 pounds and is the strongest 240 pounds in football. Ray uses a forearm better than anyone I've ever seen; when he swings it up into someone's face, it's a lethal weapon. Red should have lined up against someone smaller. Ray's used to beating people's heads in, and he enjoys it, but he looked down at Red Mack and he said, "Oh, no, I can't go against this guy."

Red looked up at Ray and said, "Get in here, you sonuvabitch, and let's go."

PRELIMINARY SKIRMISHES

FEBRUARY 10

I drove downtown to the Packer offices today to pick up my mail, mostly fan mail about our victory in the first Super Bowl game, and as I came out of the building Coach Lombardi came in. I waved to him cheerfully--I have nothing against him during the off-season--and I said, "Hi, Coach."

Vince Lombardi is a short, stout man, a stump. He looked up at me and he started to speak and his jaws moved, but no words came out. He hung his head. My first thought--from force of habit, I guess--was I've done something wrong, I'm in trouble, he's mad at me. I just stood there and Lombardi started to speak again and again he opened his mouth and still he didn't say anything. I could see he was upset, really shaken.

"What is it, Coach?" I said. "What's the matter?"

Finally, he managed to say, "I had to put Paul--" He was almost stuttering. "I had to put Paul on that list," he said, "and they took him."

I didn't know what to say. I couldn't say anything. Vince had put Paul Hornung on the list of Packers eligible to be selected by the Saints, the new expansion team in New Orleans, and the Saints had taken him. Paul Hornung had been my teammate ever since I came to Green Bay in 1958, and he had been Vince's prize pupil ever since Vince came to Green Bay in 1959, and it may sound funny but I loved Paul and Vince loved Paul and everybody on the Packers loved Paul. From the stands, or on television, Paul may have looked cocky, with his goat shoulders and his blond hair and his strut, but to the people who knew him he was a beautiful guy.

I stood there, not saying anything, and Lombardi looked at me again and lowered his head and started to walk away. He took about four steps and then he turned around and said, "This is a helluva business sometimes, isn't it?"

Then he put his head down again and walked into his office.

I got to thinking about it later, and the man is a very emotional man. He is spurred to anger or to tears almost equally easily. He gets misty-eyed and he actually cries at times, and no one thinks less of him for crying. He's such a man.

JUNE 15

Practice starts a month from today, and I'm dreading it. I don't want to work that hard again. I don't want to take all that punishment again. I really don't know why I'm going to do it.

\I must get some enjoyment out of the game, though I can't say what it is. It isn't the body contact. Body contact may be fun for the defensive players, the ones who get to make the tackles, but body contact gives me only cuts and contusions, bruises and abrasions. I suppose I enjoy doing something well. I enjoy springing a back loose, making a good trap block, a good solid trap block, cutting down my man the way I'm supposed to. But I'm not quite as boyish about the whole thing as I used to be.

A couple of months ago, I was thinking seriously about retiring. Jimmy Taylor, who used to be my roommate on the Packers, and a couple of other fellows and I have a commercial diving business down in Louisiana. Jimmy, who comes from Baton Rouge and played for Louisiana State University, is a great asset to the business; he's such a hero in Louisiana I wouldn't be surprised if he ended up as governor. We've been building up the company for three years now, and this year, with Jimmy playing for the Saints--he played out his option here and jumped to New Orleans--we should really do well. He'll be able to entertain potential customers, wine them and dine them and take them to the Saints' games.

I thought of retiring so that I could devote more time to the company. And I would have retired, I believe, or at least tried to shift to the New Orleans team, if a deal hadn't come through with a man named Blaine Williams, who's in the advertising business in Green Bay. We're getting portraits made of all the players in the National Football League, and we're selling them to Kraft Foods to distribute on a nationwide basis. It can be a very lucrative thing for me, so I decided I'd better stay here in Green Bay and keep an eye on it.

Coach Lombardi heard that I was thinking about retiring--he hears everything--and he suspected I was going to use this as a wedge to demand more money. That wasn't what I had in mind, not this time.

Still, I haven't heard a word from Lombardi about a contract for this year.

JULY 5

Pat Peppler, the personnel director of the Packers, phoned today and asked me if I wanted to discuss my contract. I told him I wanted $27,500, up from $23,000 last year, and I said it isn't as much as I deserve, of course, but I'll be happy with it and I won't cause any problems, any struggle.

I mean it. I know I'm worth more than $27,500, but I don't want a contract fight over a few thousand dollars. I can remember what happened in 1963.

That was the year after I kicked three field goals in the world championship game against the New York Giants, and we won the game by three field goals, 16-7. During the 1962 season, I kicked extra points and field goals, and I was named All-Pro offensive guard, and, in general, I had a pretty good year. I came in wanting a sizable raise, and Coach Lombardi started out with the standard 10 percent he offers when he wants to give a guy a raise. I said I wanted nearly 50 percent, from $13,000 up to $19,000, and he hit the ceiling and said absolutely not. He said he'd give me $14,500 or maybe $15,000.

In the back of my mind, I was thinking about playing out my option--the one-year professional football contract allows a man to play out a second year at the same salary and then become a free agent, the way Jimmy Taylor did last year--and jumping to Denver in the rival American Football League. Denver wanted me badly.

Coach Lombardi, with his spy system, found out what I was thinking about. He has a real thing about loyalty, and he got doubly upset. He called me into his office and offered me $15,000 and said, "Look, I'm going to give you fifteen, but you have to take it today. Tomorrow, it'll be down to fourteen." I didn't take it.

I started training camp without a contract, and Vince made practice almost unbearable. Every block I threw, every move I made, was either slow or wrong or inadequate. "Move, Kramer, move," he'd scream, "you think you're worth so damn much." And the contract negotiations weren't kept at any executive level. They were held at lunch and dinner, at bedtime and during team meetings, and the rest of the coaches joined in, all of them on my back, sniping at me, taking potshots at me. I got bitter, I got jumpy, and then a lot of the other guys, my teammates, began to tease me, to ride me, and the teasing didn't sound like teasing to me because I was getting so much hell from all angles.

And then I almost exploded. We have a ritual the day before a game. The offensive linemen get together with the defensive linemen and throw passes to each other. We take turns playing quarterback, and you get to keep throwing passes until one of them is incomplete. It's a silly little game, but it loosens us up and it's fun. Every lineman's dream, of course, is to be a quarterback. So, in 1963, the day before an exhibition, we were playing this game, and I stepped up for my turn to play quarterback and Bill Austin, who was our line coach, yelled, "No, get out of there, Kramer, you can't be a quarterback."

I said, "Why not?"

And he said, "Just 'cause I said so."

There was no reason, except for the contract, and this burned me up. Later, Austin approached me in the lobby of the hotel we were staying in, and he said, "Jerry, I want to talk to you."

I said, "Look, you sonuvabitch, I don't want to talk to you at all. I don't have a word to say to you. I don't want to have anything to do with you. Stay away from me."

I was out of my head a little bit.

Bill said, "Now, now, don't be like that."

"I mean it, Bill," I said. "Stay away from me." I stopped just short of punching Austin.

That night, Coach Lombardi put me on the kickoff team, the suicide team, which is usually reserved, during exhibition games, for rookies. "The kickoff team is football's greatest test of courage," Lombardi says. "It's the way we find out who likes to hit."

I knew how dangerous the kickoff team could be. In 1961, when I was kicking off for the Packers, I had to be on the kickoff team, of course. I kicked off once against the Minnesota Vikings, the opening play of the game, and when I ran down the field, I ran straight at the wedge in front of the ballcarrier. The wedge is made up of four men, always four big and mobile men, more than 1,000 pounds' worth. One of the guys from the Minnesota wedge hit me in the chest and another scissored my legs and buckled me over backwards and then the ballcarrier stumbled onto me and pounded me into the ground and a couple of other guys ran over me and stomped me in deeper, and the result was a broken ankle. I missed eight games in 1961.

And then in 1963, for that exhibition, I found myself on the kickoff team again. I took out all my fury on the field. I was the first man down the field on every kickoff, I hit everyone who got in my way, and after the game Lombardi came up to me and said that he wasn't the vindictive type, that we could get together and settle the contract. I signed the next day for $17,500.

***

Pat Peppler told me today he would check with Coach Lombardi about my demand for $27,500.

JULY 7

Pat Peppler called back. "You can have $26,500," he said.

"If I wanted $26,500," I told him, "I would have asked for $26,500. If I'd said $44,500, I suppose Lombardi would have come back with $43,500. I want $27,500 without any fuss, without any argument."

JULY 10

"OK, it's $27,500," Pat Peppler said today. "Stop by and sign."

I'm going to forget that I ever thought about retiring. I'm going to forget that I've got a lot of money coming in. I'm going to forget that I don't really need football anymore.

I've decided to play. Let's get on with it.

2

BASIC TRAINING

JULY 14

Practice began officially yesterday for everyone except the veteran offensive and defensive linemen. We don't have to report until 6 p.m. tomorrow, Saturday, but I couldn't wait. I had to go over to the stadium this morning. It's not that I'm anxious to start the punishment, but I figured one workout today and one tomorrow would help me ease into training. Monday, we start two-a-days, which are pure hell, one workout in the morning and one in the afternoon, and if I don't get a little exercise, the two-a-days'll kill me.

Naturally, I saw Vince this morning. He asked me how I was, and, before I could tell him, he said, "You look a little heavy."

I guess I am. I was up around 265 a few weeks ago, and I'm 259 now, and I'd like to play somewhere between 245 and 250. I'm not too worried about my weight. I know I've got the best diet doctor in the world. His prize patient right now is a rookie tackle named Leon Crenshaw, from Tuskegee Institute, who reported to training camp a week ago weighing 315 pounds. Dr. Lombardi has reduced him to 302.

I started off the day by trotting three laps around the goal posts, a total of almost half a mile, not because I love running, but because Coach Lombardi insists upon this daily ritual. As long as he's been here, we've had only one fellow who didn't run his three laps, a big rookie named Royce Whittenton. When Green Bay drafted Whittenton during the winter of his senior year in college, he weighed about 240. When the coaches contacted him in the spring, he weighed 270. They told him they didn't want him to come to camp any heavier than 250, and he reported in the summer at 315 pounds. He made one lap and half of another around the goal posts and then he couldn't go any farther. Lombardi cut him from the squad before he even took calisthenics.

We had one of our little "nutcracker" drills today, a brand of torture--one on one, offensive man against defensive man--which is, I imagine, something like being in the pit. The defensive man positions himself between two huge bags filled with foam rubber, which form a chute; the offensive man, leading a ballcarrier, tries to drive the defensive man out of the chute, banging into him, head-to-head, really rattling each other, ramming each other's neck down into the chest.

The primary idea is to open a path for the ballcarrier. The secondary idea is to draw blood. I hate it. But Coach Lombardi seemed to enjoy watching every fresh collision.

Lombardi thinks of himself as the patriarch of a large family, and he loves all his children, and he worries about all of them, but he demands more of his gifted children. Lee Roy Caffey, a tough linebacker from Texas, is one of the gifted children, and Coach Lombardi is always on Lee Roy, chewing him, harassing him, cussing him. We call Lee Roy "Big Turkey," as in, "You ought to be ashamed of yourself, you big turkey," a Lombardi line. Vince kept saying during the drill today that if anyone wanted to look like an All-American, he should just step in against Caffey.

"Look at yourself, Caffey, look at yourself, that stinks," Lombardi shouted. Later, Vince added, "Lee Roy, you may think that I criticize you too much, a little unduly at times, but you have the size, the strength, the speed, the mobility, everything in the world necessary to be a great football player, except one thing: YOU'RE TOO DAMN LAZY."

During the nutcracker, Red Mack, a reserve flanker for us last year who weighs 179 pounds soaking wet, lined up against Ray Nitschke, who weighs 240 pounds and is the strongest 240 pounds in football. Ray uses a forearm better than anyone I've ever seen; when he swings it up into someone's face, it's a lethal weapon. Red should have lined up against someone smaller. Ray's used to beating people's heads in, and he enjoys it, but he looked down at Red Mack and he said, "Oh, no, I can't go against this guy."

Red looked up at Ray and said, "Get in here, you sonuvabitch, and let's go."

Recenzii

“The best behind-the-scenes glimpse of pro football ever produced.”

—The New York Times

“An unprecedented look into the gritty world of professional football. . . . Still the gold standard of sports biographies.”

—Sports Illustrated

“A classic for its insights into the game and its people, [written] with wit and without scandal or obscenity. . . . A landmark work.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Groundbreaking. . . . Candid. . . . An uncommonly frank account.”

—Chicago Tribune

“The first great professional sports diary.”

—The Boston Globe

“The gold standard for football memoirs. . . . This modern sports classic is a smart, funny and literate diary of the Packers’ successful quest to become the first team to win back-to-back Super Bowl victories.”

—The Plain Dealer

“This seminal, as-told-to diary . . . changed the way sports readers expected their heroes to sound. No more of this Grantland Rice purple prose. Schaap gave us the tough jock sounding like a real—and witty and introspective and profane—human being.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“A must read. . . . An insightful look at the sometimes-maddening methods of Lombardi and the love-hate relationship the players had with the legendary coach.”

—Green Bay Press-Gazette

“An honest, hilarious and insightful diary, with Lombardi alternately serving as the hero and the villain, the lovable leader and the soul-crushing ogre.”

—San Jose Mercury News

“This was the book that started it all—for athletes telling their stories, for sportswriters going in depth, for great athletic tales being bound between the covers. Dick Schaap’s classic is timeless. Required reading for anyone who loves sports or sportswriting.”

—Mitch Albom

“One of the great sports books of all time.” —Billy Crystal

“Kramer detailed the 1967 championship season in an understated, respectful tone, but showed a keen eye for details the fan would never glimpse.”

—The Baltimore Sun

“One of the rarest of things—a sports book written in English by an adult.”

—Jimmy Breslin

“Daring stuff for its time, revealing how athletes really act, talk and think back when such candor was taboo.”

—Charlotte Observer

“A no-holds-barred diary. . . . One really gets a sense of the physical, mental and emotional agonies players can go through in a season.”

—Orlando Sentinel

“[Kramer is] observant, honest, sensitive and a bone-crusher at right guard.”

—The Oregonian

“The ultimate football diary. . . . Detailed and dramatic. . . . Kramer’s description of his decisive block against Jethro Pugh at the goal line in the waning seconds [of the Ice Bowl] . . . is as fresh and raw as the minus-15-degree weather at kickoff.”

—Tampa Tribune

“In my life as a writer and reader, there are only a few books that I’ve read over and over again for the sheer pleasure of the experience. Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay is the only sports book among them. I loved it when I was a teenage, and I love it still today.”

—David Maraniss, author of When Pride Still Mattered

—The New York Times

“An unprecedented look into the gritty world of professional football. . . . Still the gold standard of sports biographies.”

—Sports Illustrated

“A classic for its insights into the game and its people, [written] with wit and without scandal or obscenity. . . . A landmark work.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Groundbreaking. . . . Candid. . . . An uncommonly frank account.”

—Chicago Tribune

“The first great professional sports diary.”

—The Boston Globe

“The gold standard for football memoirs. . . . This modern sports classic is a smart, funny and literate diary of the Packers’ successful quest to become the first team to win back-to-back Super Bowl victories.”

—The Plain Dealer

“This seminal, as-told-to diary . . . changed the way sports readers expected their heroes to sound. No more of this Grantland Rice purple prose. Schaap gave us the tough jock sounding like a real—and witty and introspective and profane—human being.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“A must read. . . . An insightful look at the sometimes-maddening methods of Lombardi and the love-hate relationship the players had with the legendary coach.”

—Green Bay Press-Gazette

“An honest, hilarious and insightful diary, with Lombardi alternately serving as the hero and the villain, the lovable leader and the soul-crushing ogre.”

—San Jose Mercury News

“This was the book that started it all—for athletes telling their stories, for sportswriters going in depth, for great athletic tales being bound between the covers. Dick Schaap’s classic is timeless. Required reading for anyone who loves sports or sportswriting.”

—Mitch Albom

“One of the great sports books of all time.” —Billy Crystal

“Kramer detailed the 1967 championship season in an understated, respectful tone, but showed a keen eye for details the fan would never glimpse.”

—The Baltimore Sun

“One of the rarest of things—a sports book written in English by an adult.”

—Jimmy Breslin

“Daring stuff for its time, revealing how athletes really act, talk and think back when such candor was taboo.”

—Charlotte Observer

“A no-holds-barred diary. . . . One really gets a sense of the physical, mental and emotional agonies players can go through in a season.”

—Orlando Sentinel

“[Kramer is] observant, honest, sensitive and a bone-crusher at right guard.”

—The Oregonian

“The ultimate football diary. . . . Detailed and dramatic. . . . Kramer’s description of his decisive block against Jethro Pugh at the goal line in the waning seconds [of the Ice Bowl] . . . is as fresh and raw as the minus-15-degree weather at kickoff.”

—Tampa Tribune

“In my life as a writer and reader, there are only a few books that I’ve read over and over again for the sheer pleasure of the experience. Jerry Kramer’s Instant Replay is the only sports book among them. I loved it when I was a teenage, and I love it still today.”

—David Maraniss, author of When Pride Still Mattered