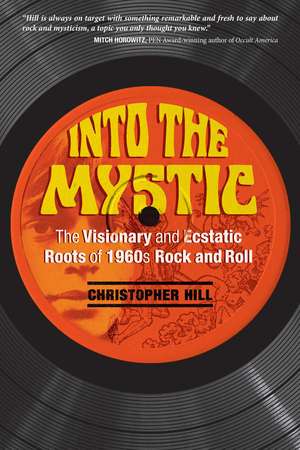

Into the Mystic: The Visionary and Ecstatic Roots of 1960s Rock and Roll

Autor Christopher Hillen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 oct 2017

Exploring how 1960s rock and roll music became a school of visionary art, Christopher Hill shows how music raised consciousness on both the individual and collective levels to bring about a transformation of the planet. The author traces how rock and roll rose from the sacred music of the African Diaspora, harnessing its ecstatic power for evoking spiritual experiences through music. He shows how the British Invasion, beginning with the Beatles in the early 1960s, acted as the “detonator” to explode visionary music into the mainstream. He explains how 60s rock and roll made a direct appeal to the imaginations of young people, giving them a larger set of reference points around which to understand life. Exploring the sources 1960s musicians drew upon to evoke the initiatory experience, he reveals the influence of European folk traditions, medieval Troubadours, and a lost American history of ecstatic politics and shows how a revival of the ancient use of psychedelic substances was the strongest agent of change, causing the ecstatic, mythic, and sacred to enter the consciousness of a generation.

Preț: 73.45 lei

Preț vechi: 97.43 lei

-25% Nou

Puncte Express: 110

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.05€ • 15.31$ • 11.84£

14.05€ • 15.31$ • 11.84£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781620556429

ISBN-10: 1620556421

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 23 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

ISBN-10: 1620556421

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 23 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

Notă biografică

Christopher Hill has written about rock and roll music in the pages of Spin, Record Magazine, International Musician, Chicago Magazine, Downbeat, Deep Roots Magazine, and other national and regional publications. His work has been anthologized in The Rolling Stone Record Review, and he is the author of Holidays and Holy Nights. Currently a contributing editor at Deep Roots Magazine, he lives in Madison, Wisconsin.

Extras

Chapter 1

An Experience of Power

The Unsuspected Immigrant and the Invisible Institution Musicologists have devoted a lot of energy to the question of where the name rock and roll comes from. A likely source is the ring shout. When the shout takes on its own momentum, they are rocking. “I gotta rock, you gotta rock” says the shout “Run Jeremiah Run.” When the spirit is really moving through the congregation, they are rocking the church.

But wait--haven’t we always heard that to “rock and roll” means to have sex? Yep. So does it mean sex? Yes. Does it mean religious ecstasy? Yes. One of the gifts of the Black Church to spirituality in general is the insight that the sensual and the sacred are, in a mystery, the same thing. It is this that made the transit from church to jukebox not simply a case of parlaying sacred tradition into hits, as if the spiritual part of the music was a clearly marked zone that the performers could just step out of. In turning from gospel to soul the musician is not so much moving from sacred to secular, leaving his calling for the World, but shifting the emphasis from one part of the spiritual spectrum toward another.

The standard narrative about the origin of rock and roll as a music is that it came out of the encounter of country music and the blues. This isn’t exactly wrong but it almost willfully ignores the glaringly obvious affiliation with gospel music.

The blues are often regarded as the primordial source of black American music, indeed of modern American popular music in general. But the blues are not the primordial music of African America. The blues and gospel music started to gain popularity in roughly the same era--around the turn of the twentieth century--and, for that matter, were both heard as novelties at the time. In the long story of African-American music, the sacred precedes the secular. The roots of gospel are in the spirituals, which date to the earliest slave culture, generations before anyone sang anything that people called the blues. A truer picture is to see the blues and rock and roll as related offshoots of African-American sacred music.

As musical forms, the blues and rock and roll are very similar, but the performance of rock and roll--and the audience participation inspired by it--is modeled, consciously or unconsciously, on the liturgical practices of the gospel church. What most distinguishes rock and roll from the blues is what most links it to gospel music--the pursuit of ecstatic release as the goal of the performance. The gospel belief that music and motion can effect a change in consciousness--as well as the conviction that the congregation/dancers are getting a purchase on freedom that might outlast the performance--reappears more obviously in soul and rock and roll than it does in the blues.

In support of the gospel origins of rock and roll we can call on some of the great names to testify. Elvis Presley tells us in his 1968 “Comeback Special” that his rock and roll is essentially gospel. While young bohemians in London were hunting out Elmore James records in the early ’60s, up in Liverpool the Beatles were apparently not listening to the blues at all. Aside from early rock and roll, the stuff the Beatles seemed to like, based on the songs they covered, was black pop that had a church lineage--soul music and girl groups.

Gospel music is the elephant in the room when it comes to rock historiography. The blues is a medium of individual artists, outlaw heroes, easier for bohemians to admire and identify with than a faith community. For most rock critics, the juke joint is easier to negotiate (at least imaginatively) than the storefront church. And for many white intellectuals, there is a double barrier to empathy with gospel music--both race and religion.

The blues could be detached from its cultural matrix and listened to as pure music more easily than gospel. The blues were a genre of entertainment. Gospel music underpinned a society and a way of life.

In any decent history of rock music you will of course find blues musicians discussed, but you’ll have to look harder for gospel singers. Gospel may be cited as an influence, but individual artists are almost never dealt with at length. There are some seventeen blues musicians represented in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There are two gospel acts--Mahalia Jackson and the Soul Stirrers.

The future historian of ecstasy will come to see that spiritual impulses are transmitted along unpredictable and paradoxical paths. By the late 1950s young white Americans were dancing en masse to music that was a product of centuries of African American spiritual practice. The lesson that what is trivial through one lens can be mighty through another will be another valuable discovery by our ecstatic historian.

The music began to teach these young people to expect an experience of the embodied spirit in their dancing and to look for a kind of truth and consequentiality in their music. They absorbed the gospel knowledge that liberation and ecstasy could come by way of popular music, and that it could leave an imprint on history as well as on the individual soul. That the music in this lineage could connect the divine and the mundane was a message that never left the music. It carried the code through every change and crisis. Sometimes the power was more potential than actual, but it was always there. The promise was not lost on the cohort of young people who would create the 1960s heyday of rock and roll.

An Experience of Power

The Unsuspected Immigrant and the Invisible Institution Musicologists have devoted a lot of energy to the question of where the name rock and roll comes from. A likely source is the ring shout. When the shout takes on its own momentum, they are rocking. “I gotta rock, you gotta rock” says the shout “Run Jeremiah Run.” When the spirit is really moving through the congregation, they are rocking the church.

But wait--haven’t we always heard that to “rock and roll” means to have sex? Yep. So does it mean sex? Yes. Does it mean religious ecstasy? Yes. One of the gifts of the Black Church to spirituality in general is the insight that the sensual and the sacred are, in a mystery, the same thing. It is this that made the transit from church to jukebox not simply a case of parlaying sacred tradition into hits, as if the spiritual part of the music was a clearly marked zone that the performers could just step out of. In turning from gospel to soul the musician is not so much moving from sacred to secular, leaving his calling for the World, but shifting the emphasis from one part of the spiritual spectrum toward another.

The standard narrative about the origin of rock and roll as a music is that it came out of the encounter of country music and the blues. This isn’t exactly wrong but it almost willfully ignores the glaringly obvious affiliation with gospel music.

The blues are often regarded as the primordial source of black American music, indeed of modern American popular music in general. But the blues are not the primordial music of African America. The blues and gospel music started to gain popularity in roughly the same era--around the turn of the twentieth century--and, for that matter, were both heard as novelties at the time. In the long story of African-American music, the sacred precedes the secular. The roots of gospel are in the spirituals, which date to the earliest slave culture, generations before anyone sang anything that people called the blues. A truer picture is to see the blues and rock and roll as related offshoots of African-American sacred music.

As musical forms, the blues and rock and roll are very similar, but the performance of rock and roll--and the audience participation inspired by it--is modeled, consciously or unconsciously, on the liturgical practices of the gospel church. What most distinguishes rock and roll from the blues is what most links it to gospel music--the pursuit of ecstatic release as the goal of the performance. The gospel belief that music and motion can effect a change in consciousness--as well as the conviction that the congregation/dancers are getting a purchase on freedom that might outlast the performance--reappears more obviously in soul and rock and roll than it does in the blues.

In support of the gospel origins of rock and roll we can call on some of the great names to testify. Elvis Presley tells us in his 1968 “Comeback Special” that his rock and roll is essentially gospel. While young bohemians in London were hunting out Elmore James records in the early ’60s, up in Liverpool the Beatles were apparently not listening to the blues at all. Aside from early rock and roll, the stuff the Beatles seemed to like, based on the songs they covered, was black pop that had a church lineage--soul music and girl groups.

Gospel music is the elephant in the room when it comes to rock historiography. The blues is a medium of individual artists, outlaw heroes, easier for bohemians to admire and identify with than a faith community. For most rock critics, the juke joint is easier to negotiate (at least imaginatively) than the storefront church. And for many white intellectuals, there is a double barrier to empathy with gospel music--both race and religion.

The blues could be detached from its cultural matrix and listened to as pure music more easily than gospel. The blues were a genre of entertainment. Gospel music underpinned a society and a way of life.

In any decent history of rock music you will of course find blues musicians discussed, but you’ll have to look harder for gospel singers. Gospel may be cited as an influence, but individual artists are almost never dealt with at length. There are some seventeen blues musicians represented in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There are two gospel acts--Mahalia Jackson and the Soul Stirrers.

The future historian of ecstasy will come to see that spiritual impulses are transmitted along unpredictable and paradoxical paths. By the late 1950s young white Americans were dancing en masse to music that was a product of centuries of African American spiritual practice. The lesson that what is trivial through one lens can be mighty through another will be another valuable discovery by our ecstatic historian.

The music began to teach these young people to expect an experience of the embodied spirit in their dancing and to look for a kind of truth and consequentiality in their music. They absorbed the gospel knowledge that liberation and ecstasy could come by way of popular music, and that it could leave an imprint on history as well as on the individual soul. That the music in this lineage could connect the divine and the mundane was a message that never left the music. It carried the code through every change and crisis. Sometimes the power was more potential than actual, but it was always there. The promise was not lost on the cohort of young people who would create the 1960s heyday of rock and roll.

Cuprins

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

A School of Vision

1 An Experience of Power

The Unsuspected Immigrant and the Invisible Institution

2 The Isle Is Full of Noises

The Meaning of the British Invasion

3 The Western Rim

Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the California Apocalypse

4 The Chimes of Freedom

Bob Dylan, Folk-Rock, and Deep America

5 The Vision of the Beloved

Troubadours, Love Songs, and the Pretty Ballerina

6 Earthquake Country

The Grateful Dead, Acid, and the Mythic Life

7 Saving England

The Beatles and the World of Sgt. Pepper

8 My Name Is Called Disturbance

The Rolling Stones and the Lord of Misrule

9 The Sorrowful Mysteries

Van Morrison and Astral Weeks

10 The Proverbs of Hell

The Journey of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground

11 The Vision of Childhood

The Incredible String Band and British Psychedelia

12 An Experience of Power

Zenta New Year, 1968, the Grande Ballroom, Detroit

Afterword

Notes

Bibliography

Index

INTRODUCTION

A School of Vision

1 An Experience of Power

The Unsuspected Immigrant and the Invisible Institution

2 The Isle Is Full of Noises

The Meaning of the British Invasion

3 The Western Rim

Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the California Apocalypse

4 The Chimes of Freedom

Bob Dylan, Folk-Rock, and Deep America

5 The Vision of the Beloved

Troubadours, Love Songs, and the Pretty Ballerina

6 Earthquake Country

The Grateful Dead, Acid, and the Mythic Life

7 Saving England

The Beatles and the World of Sgt. Pepper

8 My Name Is Called Disturbance

The Rolling Stones and the Lord of Misrule

9 The Sorrowful Mysteries

Van Morrison and Astral Weeks

10 The Proverbs of Hell

The Journey of Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground

11 The Vision of Childhood

The Incredible String Band and British Psychedelia

12 An Experience of Power

Zenta New Year, 1968, the Grande Ballroom, Detroit

Afterword

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

"Hill’s book will appeal to wide audiences, and fans of classic rock will be particularly ecstatic about the many enlightening (and potentially unexpected) spiritual facts to be found here."

“I have rarely read a book about the occult and modern culture with so many original insights. Christopher Hill zigs when others zag. He is always on target with something remarkable and fresh to say about rock and mysticism, a topic you only thought you knew.”

“Like a third eye opening, Into the Mystic illuminates the spiritual awakening that gave popular music its messianic fervor in the renaissance era that heralded the 1960s. The scope of Christopher Hill’s inquiry refracts like a psychedelic prism, with a sense of wonder at the tale unfolding and an appreciation of why it continues to fascinate and resonate within our highest consciousness.”

“What would a history look like that took the rhythms, beats, dances, and trance states of blues, gospel, and rock ’n’ roll as seriously as it took elections, wars, and arrogant men? It would be a poetic history of numinous desire, ecstatic release, and freedom. It would intuit and then trace an African-American-British visionary tradition aching as much with the sufferings of American chattel slavery and the psychedelic trips of the counterculture as the mythical channelings of William Blake. It would not look away from either the utopian hopes or the horrible failures and fundamentalist backlashes. It would look, in fact, like this weird and wonderful book.”

“Into the Mystic is a fascinating and inspiring read, providing extensive knowledge and brilliant insights carried by eloquent and, at times, poetic writing. And most important, it’s a compelling articulation of the centrality of visionary art--and in particular 1960s rock-and-roll music--in the promise that ‘the division between Heaven and Earth’ can be repealed. Christopher Hill places the rock music of the 1960s in its proper historical lineage as a cultural phenomenon far beyond mere entertainment, indeed central to the consciousness transformation revolution--the psychedelic renaissance that seemed to stall or at least dramatically wane in the 1970s. An erudite, eloquent, and potent love song to the liberating spirit of 1960s rock music--its connection to the lineage of ‘the secret garden’ (‘the secret eternal revolution’) and ‘the ancient dance’--and its relevance to the continuing urgent need for a yet deeper liberation of soul and society. A treasure trove of brilliant and unexpected revelations.”

"From the time Chris started contributing reviews to Record Magazine, up to the present day, I’ve thought, and told others, he was, on any given day, the finest music writer in this country, and one of the best in the world. With Into the Mystic: The Visionary and Ecstatic Roots of 1960s Rock and Roll I rest my case. "

“Christopher Hill is an intelligent and insightful critic and his enthusiasm for his subject tends to be infectious. He writes here an ambitious but not overly broad commentary on the emergence of a Dionysiac tradition of sixties rock and roll taking place in the midst of an Apollonian power structure collapsing under its own weight. .. whether you accept his thesis or not, he charts many hitherto little-traveled byways and offers up many intriguing theories…”

"Into the Mystic proves rich with information overall, and Hill makes some fascinating points about the cultural, historical and biographical tributaries that flow together to create a given band’s esthetic or style….(T)hough Hill’s background is in music journalism, he’s often at his most interesting when discussing Rimbaud or Sufism or troubadours or slavery."

"(Hill) quite literally turns on the reader as much as the music did over 50 years ago. . . .(He) offers a liberating perspective that will make you see the songs you know by heart in a brand new life. It truly is a revelation to feel your way through the energy that shifted cultural perceptions."

"If you want to be entertained by an often knowledgeable exegesis of the ecstatic and mystic content of the music of the 1960’s, then this is the book for you. Helped by a flowing style, the author has an excellent feel for the music, which, somehow, he manages to convey into words (no mean feat)."

“I have rarely read a book about the occult and modern culture with so many original insights. Christopher Hill zigs when others zag. He is always on target with something remarkable and fresh to say about rock and mysticism, a topic you only thought you knew.”

“Like a third eye opening, Into the Mystic illuminates the spiritual awakening that gave popular music its messianic fervor in the renaissance era that heralded the 1960s. The scope of Christopher Hill’s inquiry refracts like a psychedelic prism, with a sense of wonder at the tale unfolding and an appreciation of why it continues to fascinate and resonate within our highest consciousness.”

“What would a history look like that took the rhythms, beats, dances, and trance states of blues, gospel, and rock ’n’ roll as seriously as it took elections, wars, and arrogant men? It would be a poetic history of numinous desire, ecstatic release, and freedom. It would intuit and then trace an African-American-British visionary tradition aching as much with the sufferings of American chattel slavery and the psychedelic trips of the counterculture as the mythical channelings of William Blake. It would not look away from either the utopian hopes or the horrible failures and fundamentalist backlashes. It would look, in fact, like this weird and wonderful book.”

“Into the Mystic is a fascinating and inspiring read, providing extensive knowledge and brilliant insights carried by eloquent and, at times, poetic writing. And most important, it’s a compelling articulation of the centrality of visionary art--and in particular 1960s rock-and-roll music--in the promise that ‘the division between Heaven and Earth’ can be repealed. Christopher Hill places the rock music of the 1960s in its proper historical lineage as a cultural phenomenon far beyond mere entertainment, indeed central to the consciousness transformation revolution--the psychedelic renaissance that seemed to stall or at least dramatically wane in the 1970s. An erudite, eloquent, and potent love song to the liberating spirit of 1960s rock music--its connection to the lineage of ‘the secret garden’ (‘the secret eternal revolution’) and ‘the ancient dance’--and its relevance to the continuing urgent need for a yet deeper liberation of soul and society. A treasure trove of brilliant and unexpected revelations.”

"From the time Chris started contributing reviews to Record Magazine, up to the present day, I’ve thought, and told others, he was, on any given day, the finest music writer in this country, and one of the best in the world. With Into the Mystic: The Visionary and Ecstatic Roots of 1960s Rock and Roll I rest my case. "

“Christopher Hill is an intelligent and insightful critic and his enthusiasm for his subject tends to be infectious. He writes here an ambitious but not overly broad commentary on the emergence of a Dionysiac tradition of sixties rock and roll taking place in the midst of an Apollonian power structure collapsing under its own weight. .. whether you accept his thesis or not, he charts many hitherto little-traveled byways and offers up many intriguing theories…”

"Into the Mystic proves rich with information overall, and Hill makes some fascinating points about the cultural, historical and biographical tributaries that flow together to create a given band’s esthetic or style….(T)hough Hill’s background is in music journalism, he’s often at his most interesting when discussing Rimbaud or Sufism or troubadours or slavery."

"(Hill) quite literally turns on the reader as much as the music did over 50 years ago. . . .(He) offers a liberating perspective that will make you see the songs you know by heart in a brand new life. It truly is a revelation to feel your way through the energy that shifted cultural perceptions."

"If you want to be entertained by an often knowledgeable exegesis of the ecstatic and mystic content of the music of the 1960’s, then this is the book for you. Helped by a flowing style, the author has an excellent feel for the music, which, somehow, he manages to convey into words (no mean feat)."

Descriere

Explores the visionary, mystical, and ecstatic traditions that influenced the music of the 1960s