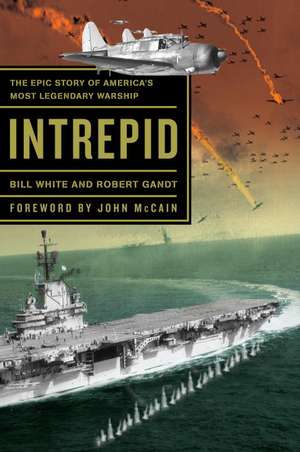

Intrepid

Autor Bill White, Robert Gandten Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 sep 2009

The USS Intrepid is a warship unlike any other. Since her launching in 1943, the 27,000-ton, Essex-class aircraft carrier has sailed into harm’s way around the globe. During World War II, she fought her way across the Pacific—Kwajalein, Truk, Peleliu, Formosa, the Philippines, Okinawa—surviving kamikaze and torpedo attacks and covering herself with glory. The famous ship endured to become a Cold War attack carrier, recovery ship for America’s first astronauts, and a three-tour combatant in Vietnam.

In a riveting narrative based on archival research and interviews with surviving crewmen, authors Bill White and Robert Gandt take us inside the war in the Pacific. We join Intrepid’s airmen at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, in October 1944, as they gaze in awe at the apparitions beneath them: five Japanese battleships, including the dreadnoughts Yamato and Musashi, plus a fleet of heavily armored cruisers and destroyers. The sky fills with multihued bursts of anti-aircraft fire. The flak, a Helldiver pilot would write in his action report, “was so thick you could get out and walk on it.” Half a dozen Intrepid aircraft are blown from the sky, but they sink the Musashi. A few months later, off Okinawa, they again meet her sister ship, the mighty Yamato. In a two-hour tableau of hellfire and towering explosions, Intrepid’s warplanes help send the super-battleship and 3,000 Japanese crewmen to the bottom of the sea.

We’re next to nineteen-year-old Alonzo Swann in Gun Tub 10 aboard Intrepid as he peers over the breech of a 20-mm anti-aircraft gun. He’s heard of kamikazes, but until today he’s never seen one. Swann and his fellow gunners are among the few African Americans assigned to combat duty in the U.S. Navy of 1944. Blazing away at the diving Japanese Zero, Swann realizes with a dreadful certainty where it will strike: directly into Gun Tub 10.

The authors follow Intrepid’s journey to Vietnam. “MiG-21 high!” crackles the voice of Lt. Tony Nargi in his F-8 Crusader. It is 1968, and Intrepid is again at war. Launching from Yankee Station in the Tonkin Gulf, Nargi and his wingman have intercepted a flight of Russian-built supersonic fighters. Minutes later, after a swirling dogfight over North Vietnam, Nargi—and Intrepid—have added another downed enemy airplane to their credit.

Intrepid: The Epic Story of America’s Most Legendary Warship brings a renowned ship to life in a stirring tribute complete with the personal recollections of those who served aboard her, dramatic photographs, time lines, maps, and vivid descriptions of Intrepid’s deadly conflicts. More than a numbers-and-dates narrative, Intrepid is the story of people—those who sailed in her, fought to keep her alive, perished in her defense—and powerfully captures the human element in this saga of American heroism.

Preț: 120.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.08€ • 24.68$ • 19.24£

23.08€ • 24.68$ • 19.24£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767929981

ISBN-10: 0767929985

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 2 8 PAGE B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Crown

ISBN-10: 0767929985

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 2 8 PAGE B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Crown

Notă biografică

BILL WHITE is president of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum and the Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund. ROBERT GANDT is a former U.S. Navy fighter pilot and Delta Air Lines captain. His numerous previous books include the definitive work on naval aviation, Bogeys and Bandits, which was adapted for the television series Pensacola: Wings of Gold.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Call to Arms

In mare in coelo (On the sea and in the air)

--Motto given to USS Intrepid on her commissioning day

August 16, 1943

Capt. Thomas L. Sprague, USN, squinted in the harsh sunlight. It was a typical Chesapeake summer early afternoon, the humidity clinging to the atmosphere like a damp blanket. Sprague could feel the perspiration trickling beneath the starched white cotton of his service dress uniform.

For nearly three decades Tom Sprague had waited for this day. He had served for what seemed a lifetime in a budget-slashed, promotionless, peacetime Navy. Finally Sprague was getting his first major command.

And what a command. Sprague's new vessel was one of the most formidable warships ever built, the third example of the fast new Essex-class aircraft carriers. With a full complement of a hundred warplanes and nearly 4,000 crew, the new carrier displaced 36,000 tons and could slice through the ocean at a speed of 33 knots.

Her name was Intrepid, and she was the fourth U.S. Navy ship of the line to bear the distinguished title. This new Intrepid was named in honor of an armed ketch that had fought with distinction at Tripoli in 1803. She was constructed at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. in Virginia. Her ceremonial keel-laying in December 1941 had nearly coincided with the Japanese attack on the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Getting Intrepid into service became a matter of national urgency. Instead of the normal three years, Intrepid had to be ready for duty in a year and a half.

When Tom Sprague entered the Naval Academy in 1913, he couldn't have guessed the historical twists and reversals that would shape his career. He received his commission in 1917, just in time to see duty as a surface officer escorting convoys across the Atlantic in World War I. Correctly sensing the future importance of naval aviation, he applied for flight training and was designated a naval aviator in 1921.

During the doldrums of the twenties and thirties, Sprague rotated through a succession of staff jobs, commanded a scouting squadron, became air officer aboard the carrier USS Saratoga, and eventually rose to the post of superintendent of naval air training at Pensacola. In 1940 he was assigned as executive officer of the carrier USS Ranger, then briefly commanded the newly constructed escort carrier USS Charger. Even in the plodding, peacetime Navy, it was clear that Tom Sprague was an officer on his way up.

On this hazy August day, Sprague knew he ought to feel a glow of contentment. This was the crowning moment of a successful military career, the prize he had dreamed about for his entire adult life. But the sweetness of the moment was tinged with a sense of foreboding. Hanging like a dark cloud over the celebration was the news from the Pacific. Four large American aircraft carriers had been lost in battle with the Imperial Japanese Navy. In May of the previous year, USS Lexington was torpedoed and sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea. USS Yorktown was lost to Japanese bombers and torpedo planes in the Battle of Midway. USS Wasp, torpedoed off Guadalcanal, went down in September 1942. A month later USS Hornet, the carrier from whose deck Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle's raiders launched the first attack on Japan, was sunk by dive-bombers and aerial torpedoes in the Battle of Santa Cruz Island. The Navy was desperately short of aircraft carriers.

No other U.S. military service was as steeped in centuries-old tradition as the Navy. The ritual of commissioning a new ship, like many U.S. Navy traditions, was adopted from the British Navy. It was a symbolic birthing, a way of giving "life" to an inanimate, newly constructed vessel. Tom Sprague, as traditional as any sailor of his generation, was sticking with the script.

More than a hundred guests--women in long skirts and sun hats, men in summer suits and in the uniforms of all the services--stood on Intrepid's gleaming flight deck at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Each division of the ship's new crew, resplendent in their dress whites, stood in neat rows facing the elevated podium. The band was playing a medley of Sousa marches and traditional military tunes.

Standing with Sprague on the podium was an assortment of Navy brass, including Rear Adm. Calvin Durgin; Cdr. Dick Gaines, who was Intrepid's new executive officer; and the guest of honor, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Artemus Gates.

The crowd stood for the playing of the national anthem. Then came the invocation, followed by the ceremonial turning over of the ship by the commandant to the new captain. Captain Sprague read the orders appointing him to command the new warship. His first act as Intrepid's new captain was to order the ship's ensign and her commissioning pennant--a long red, white, and blue streamer--hoisted. The ship's bell rang, and the watch was set. Assistant Secretary Gates delivered an address, followed by the pipe-down order and the retreat.

The new ship had just taken on a life of her own. The band struck up, and the crowd broke into applause.

There was a reception on the hangar deck, with more music by the ship's band, congratulatory talk, handshakes, and farewells. Then Tom Sprague and his crew changed uniforms and went to work. They didn't have the luxury of a long shakedown cruise, publicity tours, or visits to exotic ports of call. There was a war on. Time was short.

They had, in fact, less than four months.

First.

First skipper, first day at sea, first round of ammunition fired. In the early life of a new warship, there came a succession of such events. When the warship was an aircraft carrier, there were some unique firsts: first landing, first launch, first combat sortie flown by the carrier's aircraft, first crash.

It was October 16, 1943, and Intrepid was about to notch her first arrested landing. Behind the ship trailed a long white wake, glistening in the autumn sun. A steady 20-knot wind blew straight down the flight deck. This was a carrier's raison d'etre and her primary function. Her armament, crew, massive displacement, and gleaming flight deck were irrelevant without the ability to launch and recover warplanes.

Turning into the groove--the final approach behind the ship--was a Grumman F6F Hellcat. To no one's surprise, the honor of making Intrepid's first arrested landing was going to Cdr. A. M. Jackson, commander of Air Group 8, Intrepid's newly assigned air group. Under the watchful eye of the LSO--the landing signal officer--on his platform at the aft port deck edge, Jackson landed the Hellcat squarely in the middle of the arresting cables, snatching a wire with his tailhook, logging the first of more than 100,000 arrested landings aboard this ship.

In early October, with Air Group 8's full complement of F6F-3 Hellcats, SB2C-1 dive-bombers, and TBF torpedo bombers aboard, Intrepid headed for the benign waters of the Caribbean. In the Gulf of Paria, near Trinidad, Intrepid's crew and airmen began rehearsing the tenuous, intricate choreography of carrier flight operations.

There were mishaps. Bombing Squadron 8 had just received the new and troublesome Curtiss SB2C-1 Helldiver and was still working out the dive-bomber's many handling problems. Many of the air group's aviators were fresh out of flight training. Most of the "traps"--arrested landings--were routine, with the plane's tailhook snagging one of the sixteen arresting cables strung across the deck. But not all. A few missed the wires and careened into the barricade, the cabled fence at the end of the landing area that protected the parked airplanes, equipment, and crewmen on the forward deck. Except for some damage to airplanes, none of the incidents was serious. There was no loss of life.

By October 27 Captain Sprague was satisfied. He turned Intrepid to the north and headed back to Norfolk. In the next few weeks there were more sea trials off the Atlantic coast, including a winter trip north to Maine without the air group. On November 30 Intrepid went back into port for final storing and provisioning.

Finally, on December 3, 1943, with a full complement of crew and aircraft, Intrepid sailed out of Norfolk, bound for the far end of the world. For most of the crew--and for the base where Intrepid had come to life--it was a sentimental departure. No one knew what lay ahead, but they all had the clear sense that Intrepid would not soon return.

As all seagoing Navy men knew, a new ship headed to war needed luck. Before Intrepid had even reached the Pacific, her luck turned bad. Looking back on that day, some would say it was an omen.

The Panama Canal was a tight squeeze for any capital ship. The passage had been completed at the turn of the century, and even then it could barely accommodate the Navy's biggest warships. For Intrepid, it turned out to be more than tight.

On December 9, 1943, she left her mooring at Colon, on the Atlantic side of the isthmus, and entered the first lock of the Panama Canal. Most of the crew gathered on deck to watch the arduous process of guiding the ship through the narrow passage. At times the ship appeared to have only a few feet of clearance on either side. Scaffolding was constructed on the flight deck, perpendicular to the bridge, to give the canal pilot better visibility.

The pilot took the carrier into the Gaillard Cut, the twisting waterway leading to the locks at Balboa. What happened next would later be the subject of finger-pointing and speculation. Midway through the narrow passage, while the ship was negotiating a left turn, the bow veered to starboard, toward a steep cliff at the waterway's edge. Though the crew put the engines into full reverse and dropped a bow anchor, the ship's momentum shoved her bow into the rocky cliff. The impact ripped a 4-by-4-foot hole in her bow and buckled several plates in her hull.

Blame for what happened--whether it was the pilot or the captain or, as some suggested, the opening of a lock that caused a surge of water--was never assigned. A later board of inquiry exonerated both the canal pilot and Intrepid's officers. The carrier had to pull into port at Balboa, Panama, where she spent five days receiving a patch job on her hull. Intrepid finally reached her destination at Alameda Naval Station in San Francisco Bay three days before Christmas, 1943.

Because of the hull damage from the canal collision, Intrepid shed her planes, then steamed 5 miles across the bay to the Hunters Point dry dock to receive a more permanent repair to her bow. It would be the first of many Hunters Point dry dock sessions for Intrepid, earning for her the uncomplimentary nickname "Dry I."

Thus did the crew of Intrepid celebrate the first of several consecutive holiday seasons in San Francisco. On January 6, repairs complete and the air group's aircraft back aboard, Intrepid pulled away from her mooring and slid beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, her bow pointed westward. She was on her way to join Adm. Marc Mitscher's Fifth Fleet in the Pacific, the largest armada of warships ever assembled.

The Pearl Harbor of January 1944 was a beehive of activity. Not only had the naval complex recovered from the devastation of two years earlier, but the harbor was crammed with warships (many newly constructed, like Intrepid), ramps covered with seaplanes, and thousands of servicemen, most of them enlisted in the last two years. Intrepid glided into Pearl Harbor like a new member of a fast-growing club.

Her stay in Hawaii would be brief, but long enough to make a change in her air group. Air Group 8 had been Intrepid's first, but it wasn't the one she'd take into combat. The air group and its squadrons had new orders: they would be off-loaded in Pearl Harbor and detached to the Naval Air Station in Maui.

Taking their place was Air Group 6, a battle-tested unit whose CAG, Cdr. John Phillips, had taken over from Medal of Honor winner Butch O'Hare, lost on a night fighter mission two months before. Air Group 6 had fought in almost every major engagement in the Pacific, including the Midway, Guadalcanal, and the Gilbert and Marshall Islands actions.

After conducting qualification landings with her new air group, Intrepid put to sea on January 16, bound for the Marshall Islands. Accompanied by the carriers Cabot and Essex and a screen of escort vessels, she was part of a newly formed task group that would join Task Force 58, the largest U.S. Navy task force yet assembled in World War II.

The first two targets of the operation--the islands of Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands--had been captured by U.S. Marines in November 1943 after a quick but costly amphibious assault. The next phase of the island-hopping campaign would concentrate on the Kwajalein atoll, Japan's major defense center in the Marshall Islands.

The triangular atoll, 66 miles long and 20 miles across at its widest, was the world's largest enclosed atoll. Within the reefs that rimmed Kwajalein was a landlocked lagoon used by the Japanese as a fueling and repair facility. Nearly a hundred Japanese warplanes were based on the atoll, and the entire complex bristled with fortifications and heavy guns.

The Kwajalein campaign was to be a two-pronged attack with the assault forces divided into Northern and Southern Attack Groups. The Northern Group, units of the 4th Marine Division, would seize the islands that guarded the northern approach to Kwajalein, and the Southern Group with units of the U.S. Army 7th Division would invade Kwajalein itself. Task Group 58.2, with Intrepid at its center, was assigned to the Northern Group.

The next day, January 29, 1944, Intrepid would log another first in her history: first day of combat.

2

First Blooding

The collective thunder of fifty radial engines split the morning stillness. One after the other, Air Group 6's warplanes roared down the flight deck and lumbered into the sky. First went the Hellcat fighters, followed by the slower, bomb-laden Avengers and Dauntlesses.

Captain Sprague, watching from the nav bridge, couldn't help feeling a sense of satisfaction. After five months of urgent preparation, Intrepid and its crew were about to prove their worth. This cool Pacific morning would mark their first engagement with the Japanese.

The targets were the low, brush-covered islands of Roi and Namur, 42 miles north of Kwajalein. On the larger island of Roi, the Japanese had constructed an airfield with three runways and a complex of hangars and support buildings. The islands were ringed with anti-aircraft emplacements, pillboxes, and coast defense guns. On either side of Roi and Namur were islets on which the Japanese had installed heavy guns.

The invasion of Roi and Namur was preceded by a two-day bombardment by the battleships Tennessee, Maryland, and Colorado, plus the combined guns of five cruisers and nineteen destroyers. Then came Intrepid's Air Group 6, which would strafe, bomb, and set ablaze every aircraft and building on the islands. Leading the first wave would be the F6F-3 Hellcats of Fighting Squadron 6.

In the opinions of the men who flew it, the Hellcat was the best American fighter of the war. Produced by Grumman as the replacement for the plodding, short-ranged F4F Wildcat, the Hellcat arrived at precisely the right time. The rugged fighter had a top speed of 380 mph, and though less maneuverable than its adversary, the Japanese Zero (code-named "Zeke"), the Hellcat had superior armor and higher altitude capability. Like other products of Grumman, the Hellcat was a fighter that could take terrific punishment from Japanese guns and still keep flying.

The Japanese ace Saburo Sakai described an encounter with a Grumman fighter: "I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7-mm machine guns. I turned the 20-mm cannon switch to the off position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying. I thought this very odd--it had never happened before--and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now."

From the Hardcover edition.

Call to Arms

In mare in coelo (On the sea and in the air)

--Motto given to USS Intrepid on her commissioning day

August 16, 1943

Capt. Thomas L. Sprague, USN, squinted in the harsh sunlight. It was a typical Chesapeake summer early afternoon, the humidity clinging to the atmosphere like a damp blanket. Sprague could feel the perspiration trickling beneath the starched white cotton of his service dress uniform.

For nearly three decades Tom Sprague had waited for this day. He had served for what seemed a lifetime in a budget-slashed, promotionless, peacetime Navy. Finally Sprague was getting his first major command.

And what a command. Sprague's new vessel was one of the most formidable warships ever built, the third example of the fast new Essex-class aircraft carriers. With a full complement of a hundred warplanes and nearly 4,000 crew, the new carrier displaced 36,000 tons and could slice through the ocean at a speed of 33 knots.

Her name was Intrepid, and she was the fourth U.S. Navy ship of the line to bear the distinguished title. This new Intrepid was named in honor of an armed ketch that had fought with distinction at Tripoli in 1803. She was constructed at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. in Virginia. Her ceremonial keel-laying in December 1941 had nearly coincided with the Japanese attack on the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Getting Intrepid into service became a matter of national urgency. Instead of the normal three years, Intrepid had to be ready for duty in a year and a half.

When Tom Sprague entered the Naval Academy in 1913, he couldn't have guessed the historical twists and reversals that would shape his career. He received his commission in 1917, just in time to see duty as a surface officer escorting convoys across the Atlantic in World War I. Correctly sensing the future importance of naval aviation, he applied for flight training and was designated a naval aviator in 1921.

During the doldrums of the twenties and thirties, Sprague rotated through a succession of staff jobs, commanded a scouting squadron, became air officer aboard the carrier USS Saratoga, and eventually rose to the post of superintendent of naval air training at Pensacola. In 1940 he was assigned as executive officer of the carrier USS Ranger, then briefly commanded the newly constructed escort carrier USS Charger. Even in the plodding, peacetime Navy, it was clear that Tom Sprague was an officer on his way up.

On this hazy August day, Sprague knew he ought to feel a glow of contentment. This was the crowning moment of a successful military career, the prize he had dreamed about for his entire adult life. But the sweetness of the moment was tinged with a sense of foreboding. Hanging like a dark cloud over the celebration was the news from the Pacific. Four large American aircraft carriers had been lost in battle with the Imperial Japanese Navy. In May of the previous year, USS Lexington was torpedoed and sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea. USS Yorktown was lost to Japanese bombers and torpedo planes in the Battle of Midway. USS Wasp, torpedoed off Guadalcanal, went down in September 1942. A month later USS Hornet, the carrier from whose deck Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle's raiders launched the first attack on Japan, was sunk by dive-bombers and aerial torpedoes in the Battle of Santa Cruz Island. The Navy was desperately short of aircraft carriers.

No other U.S. military service was as steeped in centuries-old tradition as the Navy. The ritual of commissioning a new ship, like many U.S. Navy traditions, was adopted from the British Navy. It was a symbolic birthing, a way of giving "life" to an inanimate, newly constructed vessel. Tom Sprague, as traditional as any sailor of his generation, was sticking with the script.

More than a hundred guests--women in long skirts and sun hats, men in summer suits and in the uniforms of all the services--stood on Intrepid's gleaming flight deck at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Each division of the ship's new crew, resplendent in their dress whites, stood in neat rows facing the elevated podium. The band was playing a medley of Sousa marches and traditional military tunes.

Standing with Sprague on the podium was an assortment of Navy brass, including Rear Adm. Calvin Durgin; Cdr. Dick Gaines, who was Intrepid's new executive officer; and the guest of honor, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Artemus Gates.

The crowd stood for the playing of the national anthem. Then came the invocation, followed by the ceremonial turning over of the ship by the commandant to the new captain. Captain Sprague read the orders appointing him to command the new warship. His first act as Intrepid's new captain was to order the ship's ensign and her commissioning pennant--a long red, white, and blue streamer--hoisted. The ship's bell rang, and the watch was set. Assistant Secretary Gates delivered an address, followed by the pipe-down order and the retreat.

The new ship had just taken on a life of her own. The band struck up, and the crowd broke into applause.

There was a reception on the hangar deck, with more music by the ship's band, congratulatory talk, handshakes, and farewells. Then Tom Sprague and his crew changed uniforms and went to work. They didn't have the luxury of a long shakedown cruise, publicity tours, or visits to exotic ports of call. There was a war on. Time was short.

They had, in fact, less than four months.

First.

First skipper, first day at sea, first round of ammunition fired. In the early life of a new warship, there came a succession of such events. When the warship was an aircraft carrier, there were some unique firsts: first landing, first launch, first combat sortie flown by the carrier's aircraft, first crash.

It was October 16, 1943, and Intrepid was about to notch her first arrested landing. Behind the ship trailed a long white wake, glistening in the autumn sun. A steady 20-knot wind blew straight down the flight deck. This was a carrier's raison d'etre and her primary function. Her armament, crew, massive displacement, and gleaming flight deck were irrelevant without the ability to launch and recover warplanes.

Turning into the groove--the final approach behind the ship--was a Grumman F6F Hellcat. To no one's surprise, the honor of making Intrepid's first arrested landing was going to Cdr. A. M. Jackson, commander of Air Group 8, Intrepid's newly assigned air group. Under the watchful eye of the LSO--the landing signal officer--on his platform at the aft port deck edge, Jackson landed the Hellcat squarely in the middle of the arresting cables, snatching a wire with his tailhook, logging the first of more than 100,000 arrested landings aboard this ship.

In early October, with Air Group 8's full complement of F6F-3 Hellcats, SB2C-1 dive-bombers, and TBF torpedo bombers aboard, Intrepid headed for the benign waters of the Caribbean. In the Gulf of Paria, near Trinidad, Intrepid's crew and airmen began rehearsing the tenuous, intricate choreography of carrier flight operations.

There were mishaps. Bombing Squadron 8 had just received the new and troublesome Curtiss SB2C-1 Helldiver and was still working out the dive-bomber's many handling problems. Many of the air group's aviators were fresh out of flight training. Most of the "traps"--arrested landings--were routine, with the plane's tailhook snagging one of the sixteen arresting cables strung across the deck. But not all. A few missed the wires and careened into the barricade, the cabled fence at the end of the landing area that protected the parked airplanes, equipment, and crewmen on the forward deck. Except for some damage to airplanes, none of the incidents was serious. There was no loss of life.

By October 27 Captain Sprague was satisfied. He turned Intrepid to the north and headed back to Norfolk. In the next few weeks there were more sea trials off the Atlantic coast, including a winter trip north to Maine without the air group. On November 30 Intrepid went back into port for final storing and provisioning.

Finally, on December 3, 1943, with a full complement of crew and aircraft, Intrepid sailed out of Norfolk, bound for the far end of the world. For most of the crew--and for the base where Intrepid had come to life--it was a sentimental departure. No one knew what lay ahead, but they all had the clear sense that Intrepid would not soon return.

As all seagoing Navy men knew, a new ship headed to war needed luck. Before Intrepid had even reached the Pacific, her luck turned bad. Looking back on that day, some would say it was an omen.

The Panama Canal was a tight squeeze for any capital ship. The passage had been completed at the turn of the century, and even then it could barely accommodate the Navy's biggest warships. For Intrepid, it turned out to be more than tight.

On December 9, 1943, she left her mooring at Colon, on the Atlantic side of the isthmus, and entered the first lock of the Panama Canal. Most of the crew gathered on deck to watch the arduous process of guiding the ship through the narrow passage. At times the ship appeared to have only a few feet of clearance on either side. Scaffolding was constructed on the flight deck, perpendicular to the bridge, to give the canal pilot better visibility.

The pilot took the carrier into the Gaillard Cut, the twisting waterway leading to the locks at Balboa. What happened next would later be the subject of finger-pointing and speculation. Midway through the narrow passage, while the ship was negotiating a left turn, the bow veered to starboard, toward a steep cliff at the waterway's edge. Though the crew put the engines into full reverse and dropped a bow anchor, the ship's momentum shoved her bow into the rocky cliff. The impact ripped a 4-by-4-foot hole in her bow and buckled several plates in her hull.

Blame for what happened--whether it was the pilot or the captain or, as some suggested, the opening of a lock that caused a surge of water--was never assigned. A later board of inquiry exonerated both the canal pilot and Intrepid's officers. The carrier had to pull into port at Balboa, Panama, where she spent five days receiving a patch job on her hull. Intrepid finally reached her destination at Alameda Naval Station in San Francisco Bay three days before Christmas, 1943.

Because of the hull damage from the canal collision, Intrepid shed her planes, then steamed 5 miles across the bay to the Hunters Point dry dock to receive a more permanent repair to her bow. It would be the first of many Hunters Point dry dock sessions for Intrepid, earning for her the uncomplimentary nickname "Dry I."

Thus did the crew of Intrepid celebrate the first of several consecutive holiday seasons in San Francisco. On January 6, repairs complete and the air group's aircraft back aboard, Intrepid pulled away from her mooring and slid beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, her bow pointed westward. She was on her way to join Adm. Marc Mitscher's Fifth Fleet in the Pacific, the largest armada of warships ever assembled.

The Pearl Harbor of January 1944 was a beehive of activity. Not only had the naval complex recovered from the devastation of two years earlier, but the harbor was crammed with warships (many newly constructed, like Intrepid), ramps covered with seaplanes, and thousands of servicemen, most of them enlisted in the last two years. Intrepid glided into Pearl Harbor like a new member of a fast-growing club.

Her stay in Hawaii would be brief, but long enough to make a change in her air group. Air Group 8 had been Intrepid's first, but it wasn't the one she'd take into combat. The air group and its squadrons had new orders: they would be off-loaded in Pearl Harbor and detached to the Naval Air Station in Maui.

Taking their place was Air Group 6, a battle-tested unit whose CAG, Cdr. John Phillips, had taken over from Medal of Honor winner Butch O'Hare, lost on a night fighter mission two months before. Air Group 6 had fought in almost every major engagement in the Pacific, including the Midway, Guadalcanal, and the Gilbert and Marshall Islands actions.

After conducting qualification landings with her new air group, Intrepid put to sea on January 16, bound for the Marshall Islands. Accompanied by the carriers Cabot and Essex and a screen of escort vessels, she was part of a newly formed task group that would join Task Force 58, the largest U.S. Navy task force yet assembled in World War II.

The first two targets of the operation--the islands of Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands--had been captured by U.S. Marines in November 1943 after a quick but costly amphibious assault. The next phase of the island-hopping campaign would concentrate on the Kwajalein atoll, Japan's major defense center in the Marshall Islands.

The triangular atoll, 66 miles long and 20 miles across at its widest, was the world's largest enclosed atoll. Within the reefs that rimmed Kwajalein was a landlocked lagoon used by the Japanese as a fueling and repair facility. Nearly a hundred Japanese warplanes were based on the atoll, and the entire complex bristled with fortifications and heavy guns.

The Kwajalein campaign was to be a two-pronged attack with the assault forces divided into Northern and Southern Attack Groups. The Northern Group, units of the 4th Marine Division, would seize the islands that guarded the northern approach to Kwajalein, and the Southern Group with units of the U.S. Army 7th Division would invade Kwajalein itself. Task Group 58.2, with Intrepid at its center, was assigned to the Northern Group.

The next day, January 29, 1944, Intrepid would log another first in her history: first day of combat.

2

First Blooding

The collective thunder of fifty radial engines split the morning stillness. One after the other, Air Group 6's warplanes roared down the flight deck and lumbered into the sky. First went the Hellcat fighters, followed by the slower, bomb-laden Avengers and Dauntlesses.

Captain Sprague, watching from the nav bridge, couldn't help feeling a sense of satisfaction. After five months of urgent preparation, Intrepid and its crew were about to prove their worth. This cool Pacific morning would mark their first engagement with the Japanese.

The targets were the low, brush-covered islands of Roi and Namur, 42 miles north of Kwajalein. On the larger island of Roi, the Japanese had constructed an airfield with three runways and a complex of hangars and support buildings. The islands were ringed with anti-aircraft emplacements, pillboxes, and coast defense guns. On either side of Roi and Namur were islets on which the Japanese had installed heavy guns.

The invasion of Roi and Namur was preceded by a two-day bombardment by the battleships Tennessee, Maryland, and Colorado, plus the combined guns of five cruisers and nineteen destroyers. Then came Intrepid's Air Group 6, which would strafe, bomb, and set ablaze every aircraft and building on the islands. Leading the first wave would be the F6F-3 Hellcats of Fighting Squadron 6.

In the opinions of the men who flew it, the Hellcat was the best American fighter of the war. Produced by Grumman as the replacement for the plodding, short-ranged F4F Wildcat, the Hellcat arrived at precisely the right time. The rugged fighter had a top speed of 380 mph, and though less maneuverable than its adversary, the Japanese Zero (code-named "Zeke"), the Hellcat had superior armor and higher altitude capability. Like other products of Grumman, the Hellcat was a fighter that could take terrific punishment from Japanese guns and still keep flying.

The Japanese ace Saburo Sakai described an encounter with a Grumman fighter: "I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7-mm machine guns. I turned the 20-mm cannon switch to the off position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying. I thought this very odd--it had never happened before--and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Eloquently written.”

—Tucson Citizen

“Vivid World War II sea and air battle descriptions.”

—Washington Times

“The story of the Intrepid is as fresh and exciting today as it was when the great ship was in the thick of the most ferocious sea battles ever. We’re so lucky to have her around to remind us of past glories and dangerous times.”

—Tom Brokaw

“USS Intrepid’s story is the story of a ship from World War II to Vietnam, the 55,000 men who served aboard her, and all those who fought so valiantly to save her for future generations. Intrepid’s story is America’s story, for as long as the flag caresses the wind and Americans believe in each other. Bill White and Robert Gandt have told it eloquently and well.” —Stephen Coonts

“No ship other than Old Ironsides herself has a name that rings more brightly in the annals of our Navy’s history than the USS Intrepid. This is an absorbing chronicle of the legendary aircraft carrier’s long service in the fleet, from her two years in the fevered carrier actions of World War II to her unlikely role, moored on a Hudson River pier, on September 11, 2001. It’s a fascinating look at how our carrier navy catapulted itself from a proud past into a limitless future. I learned something on almost every page.”

—James D. Hornfischer, author of The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors and Ship of Ghosts

“Bill White and Bob Gandt’s tale of Intrepid represents a rare then-to-now account of a fighting flattop. It’s rare because so few historic carriers remain today, let alone one that launched aircraft in World War II and Vietnam and featured in recoveries of multiple space capsules. Small wonder, then, that CV-11’s veteran sailors and aviators retain such pride in their ship.” —Barrett Tillman, author of Clash of the Carriers

From the Hardcover edition.

—Tucson Citizen

“Vivid World War II sea and air battle descriptions.”

—Washington Times

“The story of the Intrepid is as fresh and exciting today as it was when the great ship was in the thick of the most ferocious sea battles ever. We’re so lucky to have her around to remind us of past glories and dangerous times.”

—Tom Brokaw

“USS Intrepid’s story is the story of a ship from World War II to Vietnam, the 55,000 men who served aboard her, and all those who fought so valiantly to save her for future generations. Intrepid’s story is America’s story, for as long as the flag caresses the wind and Americans believe in each other. Bill White and Robert Gandt have told it eloquently and well.” —Stephen Coonts

“No ship other than Old Ironsides herself has a name that rings more brightly in the annals of our Navy’s history than the USS Intrepid. This is an absorbing chronicle of the legendary aircraft carrier’s long service in the fleet, from her two years in the fevered carrier actions of World War II to her unlikely role, moored on a Hudson River pier, on September 11, 2001. It’s a fascinating look at how our carrier navy catapulted itself from a proud past into a limitless future. I learned something on almost every page.”

—James D. Hornfischer, author of The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors and Ship of Ghosts

“Bill White and Bob Gandt’s tale of Intrepid represents a rare then-to-now account of a fighting flattop. It’s rare because so few historic carriers remain today, let alone one that launched aircraft in World War II and Vietnam and featured in recoveries of multiple space capsules. Small wonder, then, that CV-11’s veteran sailors and aviators retain such pride in their ship.” —Barrett Tillman, author of Clash of the Carriers

From the Hardcover edition.