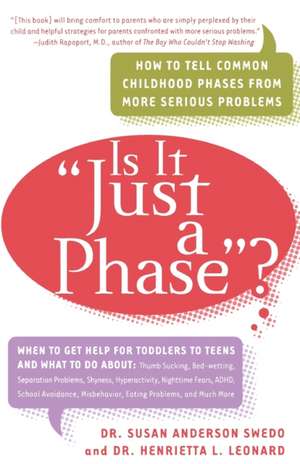

Is It Just a Phase?: How to Tell Common Childhood Phases from More Serious Problems

Autor Susan Anderson Swedo, Henrietta L. Leonarden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 1999

Is It "Just a Phase"? uniquely combines the advice of an expert pediatrician and an expert child and adolescent psychiatrist on the challenges a child faces from toddlerhood through adolescence. Drawing on real-life examples, Doctors Swedo and Leonard give concrete guidelines for determining when a behavior is a common developmental phase and when it is a more serious problem. With the latest medical research on issues that concern every parent, Is It "Just a Phase"? includes information on:

Excessive activity and ADHD

Picky eating, anorexia, and bulimia

Thumb sucking, other habits, and tic disorders

Shyness and social phobia

Excessive moodiness, depression, and bipolar disorder

Childhood fears and separation anxiety disorder

Preț: 138.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 208

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.53€ • 28.81$ • 22.29£

26.53€ • 28.81$ • 22.29£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767903912

ISBN-10: 0767903919

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767903919

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

"This book will bring comfort to parents who are simply perplexed by their child and helpful strategies for parents confronted with more serious problems."

--Judith Rapoport, M.D., author of The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing

"A must book for parents and anyone who wants to understand children."

--John J. Ratey, M.D., author of Driven to Distraction and Shadow Syndromes

"Parents concerned by the behavior of an overactive, shy, or disobedient child, or troubled by their child's bedwetting or eating problems, can find reassuring, practical advice in this accessible handbook."

--Publishers Weekly

--Judith Rapoport, M.D., author of The Boy Who Couldn't Stop Washing

"A must book for parents and anyone who wants to understand children."

--John J. Ratey, M.D., author of Driven to Distraction and Shadow Syndromes

"Parents concerned by the behavior of an overactive, shy, or disobedient child, or troubled by their child's bedwetting or eating problems, can find reassuring, practical advice in this accessible handbook."

--Publishers Weekly

Notă biografică

Dr. Susan Anderson Swedo is a pediatrician, a fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the head of behavioral pediatrics at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). She lives near Washington, D.C., with her husband and three daughters.

Dr. Henrietta L. Leonard is a child and adolescent psychiatrist in practice at Rhode Island Hospital and the training director of the child psychiatry program at Brown University School of Medicine. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband and two sons.

Dr. Henrietta L. Leonard is a child and adolescent psychiatrist in practice at Rhode Island Hospital and the training director of the child psychiatry program at Brown University School of Medicine. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, with her husband and two sons.

Extras

Introduction

"Amy, why don't you go outside and play with your cousins?" her mother, Celeste, asked.

"I don't want to. I'm busy," Amy responded, without looking up from her toys.

"Amy, I want to talk with your Grandma Rose alone for a little while, so you need to go outside and play."

"I don't want to go outside. I'm playing with my dolls," Amy whined. "If you want to have a private conversation," she continued, "why don't you go someplace else?"

"That's enough, Amy! You're going outside--right now!" Celeste got up and led her daughter to the back door. "Now, scoot!" she said and shut the door behind the reluctant eight-year-old.

"What's up, Celeste?" Rose asked her daughter-in-law as she returned to sit at the kitchen table.

"I'm worried about Amy," Celeste said. "She's been so difficult lately--always talking back to me and insisting on having her own way about everything. She's absolutely impossible!"

"She's not impossible, Celeste," Rose said soothingly. "She's just showing her spirit."

"Her spirit!" Celeste snorted. "I think it's more than that, Rose. Amy's being really obnoxious these days. It's not like her--she's always been so sweet and helpful. She'd have a smile on her face all the time, too. But, lately, all she does is sulk and sass us. I can't count the number of times I've been tempted to wash that girl's mouth out with soap."

"Have you?" Rose gasped.

"No, of course not," Celeste answered. "But the fact that I've even considered it is a sign that there's something seriously wrong with Amy. I'm really worried about her."

"Don't worry, Celeste," Rose said. "It's just a phase--Amy will grow out of it soon. All kids go through difficult stages. They have to give you some grief and go through some tough times--it's a normal part of growing up. The key to being a good parent is to help them grow out of the problem phases as quickly as possible, and not to lose your cool until they do."

"Sounds like great advice," Celeste said. "But easier said than done--she really irritates me! And how do you know for sure that it's 'just a phase'?"

"That, my dear, is the million-dollar question," Rose answered.

While it may not be worth a million dollars, the question of whether a child's behavior problems are "just a phase" or something more serious is one that parents ask frequently during the grade school years. Problem phases occur so predictably that child development experts have even given them names, such as the Terrible Twos, the Ferocious Fours, and the Sensitive Sixes. Some children are a handful from the time they enter the Terrible Twos until they leave home sixteen years later. Others, like Amy, appear to sail through their early development without problems, and then challenge their parents by exhibiting the sassy independence common to eight-year-olds or the moody rebelliousness of adolescence. Parents who are prepared for these difficult stages can change their parenting style in preparation for the expected challenges. They will have an easier time handling the problem phases, and their child will pass through them more quickly and easily. This book provides parents with the information they need to anticipate the problem phases and to be prepared for the developmental challenges that face their child.

The book's title, Is It "Just a Phase"?, alludes to the old, outdated approach to pediatric behavior problems: "It's just a phase. Ignore it and wait for her to outgrow it." Bad advice! But often a worried parent can't just ignore her child's problem behaviors. Attempting to ignore the unignorable is not only frustrating to both the parent and child during the months (or years!) that the behavior lasts, but it also impacts on the child's development, which is shaped by the behavior she's practicing and by her parents' reactions to it.

For example, if a six-year-old child's bedtime fears are dismissed as "just a phase that she's going through--ignore it!" and her parents act as if nothing's the matter, they may insist on turning off her light, giving her countless hours of needless anxiety and creating further behavior problems. Because she's afraid to go to sleep and equally afraid to lie awake in the dark, she refuses to go to bed at night, or climbs into her parents' bed in the middle of the night despite warnings against doing so. She may also experience nightmares and insomnia, which further compound the problem. On the other hand, if her parents recognize that she is entering a phase in which nighttime fears are common, they can be prepared to provide her with extra measures of comfort and security so that she quickly accepts that "there's not really a monster under my bed" and "outgrows" her fears.

Clearly, the way that the child's parents handle her developmental challenges is an important factor in determining her future development. Although physicians have always known that this was true, we have only recently learned that this is because the child's brain is "plastic," or malleable, and is molded by tnany things, including her experiences. Scientific experiments have proven that the actual size and structure of the brain can be altered by factors in the environment; some experiences, such as practicing the piano or reciting poetry, result in improved brain function, while others, like drug and alcohol use, can dramatically decrease the child's potential capabilities.

The visual system is a good example of the brain's plasticity. When a child is born, her vision is limited to blurry images and indistinct colors, but it quickly comes into sharp focus as her brain is matured by the act of "seeing." The act of processing visual images causes some nerve connections to be strengthened and others to be eliminated. This shaping process is so important that it can make the difference between perfect vision and blindness. For example, if a child is born with cataracts, her brain doesn't receive any visual input and she's "blind." If the cataracts are removed soon after birth, she will have normal vision. But if the cataracts aren't removed until the shaping process is complete (sometime before the age of four), the child will always be blind--even though her eyes are now completely normal. She can't see because her brain hasn't learned how to process the images. The visual system is an unusually dramatic example of the plasticity of the brain, and there are no similar "all or none" periods during a child's emotional development. But since early experiences have such a tremendous impact on development, it is clear that a child's behavior problems are never something to be ignored.

The chapters in part I of Is It "Just a Phase"? provide parents with strategies for helping their children cope with a variety of common developmental problems, from hyperactivity, picky eating, naughtiness, and impulsivity, to shyness, excessive fears, sadness, and social isolation. A "real life" example, similar to Amy's story, introduces each chapter. These case histories are not based on any one child (in order to protect our patients' privacy), but are composites of our experience and training. The purpose of the stories is to give you a sense of the types of problems that fall under the category of "normal" childhood behavior. A case example of a "problem" behavior is also included so that you can decide which pattern is more similar to your child's behavior. If your child's behavior is in the normal range, suggestions are provided for helping her outgrow the problem, including ways in which you, your child's teacher, and her doctor can be of assistance. If your child's behavior appears more like one of the problem behaviors that are described, then you will be referted to the appropriate chapter in the second half of the book.

The second part of Is It "Just a Phase"? focuses on the symptoms of childhood psychiatric disorders--"problem behaviors," like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In addition to a case illustration, parents are provided with a diagnostic checklist so that they can accurately assess the nature and severity of their child's symptoms. Treatment strategies are presented and rated for safety and effectiveness. Suggestions are also provided for ways in which parents can help their child continue to grow and develop appropriately, even as she is recovering from the disorder.

It should be apparent by now that there is no shame or blame in this book. The problems described here can't be blamed on either the child or her parent, and neither of them should be ashamed when they occur. Difficult phases result when developmental challenges facing the child overcome her ability to cope, just as diabetes occurs when the blood sugar content exceeds the body's ability to make insulin. Psychiatric disorders occur when the brain malfunctions--they are medical illnesses, not a punishment for a child's weak character or a parent's mistakes.

Stomach ulcers provide the perfect analogy for our changing attitude toward mental illness. For generations, doctors thought that ulcers were brought on by stress and dietary indiscretions and patients were encouraged to "take it easy and avoid spicy foods." With that prescription, some of the patients got better, just as some patients with depression or anxiety disorders get better with rest and tender, loving care. Some ulcer patients' symptoms continued to worsen on the bland diet, however--not a surprise since the treatment failed to address the cause of the symptoms. A few years ago, an Australian doctor discovered that most ulcers are the result of a bacterial infection and, since then, antibiotics have become the treatment of choice--now 95 percent of the patients improve in the first six weeks. We haven't yet found the cause of most children's psychiatric disorders, so a true "cure" isn't immediately available, but important discoveries are being made every day. Recently, for example, researchers from the National Institute of Mental Health reported that some behavior problems may be caused by strep throat infections. If so, these disorders could be "cured" by immunologic treatments and possibly prevented by long-term penicillin treatment (see chapter 17 for a complete description).

It is our fervent hope that the cause and cure of children's psychiatric disorders are nearly at hand, and that our understanding of childhood development improves to the point at which we can prevent problem phases through early interventions by parents, physicians, and teachers. Until then, it is reassuring to know that these problems are real, they can be diagnosed accurately, and they will improve when given proper care and attention. The same holds true for undesirable developmental behaviors deemed normal, for no matter what the behavior problem, it's never "just a phase" that should be ignored.

"Amy, why don't you go outside and play with your cousins?" her mother, Celeste, asked.

"I don't want to. I'm busy," Amy responded, without looking up from her toys.

"Amy, I want to talk with your Grandma Rose alone for a little while, so you need to go outside and play."

"I don't want to go outside. I'm playing with my dolls," Amy whined. "If you want to have a private conversation," she continued, "why don't you go someplace else?"

"That's enough, Amy! You're going outside--right now!" Celeste got up and led her daughter to the back door. "Now, scoot!" she said and shut the door behind the reluctant eight-year-old.

"What's up, Celeste?" Rose asked her daughter-in-law as she returned to sit at the kitchen table.

"I'm worried about Amy," Celeste said. "She's been so difficult lately--always talking back to me and insisting on having her own way about everything. She's absolutely impossible!"

"She's not impossible, Celeste," Rose said soothingly. "She's just showing her spirit."

"Her spirit!" Celeste snorted. "I think it's more than that, Rose. Amy's being really obnoxious these days. It's not like her--she's always been so sweet and helpful. She'd have a smile on her face all the time, too. But, lately, all she does is sulk and sass us. I can't count the number of times I've been tempted to wash that girl's mouth out with soap."

"Have you?" Rose gasped.

"No, of course not," Celeste answered. "But the fact that I've even considered it is a sign that there's something seriously wrong with Amy. I'm really worried about her."

"Don't worry, Celeste," Rose said. "It's just a phase--Amy will grow out of it soon. All kids go through difficult stages. They have to give you some grief and go through some tough times--it's a normal part of growing up. The key to being a good parent is to help them grow out of the problem phases as quickly as possible, and not to lose your cool until they do."

"Sounds like great advice," Celeste said. "But easier said than done--she really irritates me! And how do you know for sure that it's 'just a phase'?"

"That, my dear, is the million-dollar question," Rose answered.

While it may not be worth a million dollars, the question of whether a child's behavior problems are "just a phase" or something more serious is one that parents ask frequently during the grade school years. Problem phases occur so predictably that child development experts have even given them names, such as the Terrible Twos, the Ferocious Fours, and the Sensitive Sixes. Some children are a handful from the time they enter the Terrible Twos until they leave home sixteen years later. Others, like Amy, appear to sail through their early development without problems, and then challenge their parents by exhibiting the sassy independence common to eight-year-olds or the moody rebelliousness of adolescence. Parents who are prepared for these difficult stages can change their parenting style in preparation for the expected challenges. They will have an easier time handling the problem phases, and their child will pass through them more quickly and easily. This book provides parents with the information they need to anticipate the problem phases and to be prepared for the developmental challenges that face their child.

The book's title, Is It "Just a Phase"?, alludes to the old, outdated approach to pediatric behavior problems: "It's just a phase. Ignore it and wait for her to outgrow it." Bad advice! But often a worried parent can't just ignore her child's problem behaviors. Attempting to ignore the unignorable is not only frustrating to both the parent and child during the months (or years!) that the behavior lasts, but it also impacts on the child's development, which is shaped by the behavior she's practicing and by her parents' reactions to it.

For example, if a six-year-old child's bedtime fears are dismissed as "just a phase that she's going through--ignore it!" and her parents act as if nothing's the matter, they may insist on turning off her light, giving her countless hours of needless anxiety and creating further behavior problems. Because she's afraid to go to sleep and equally afraid to lie awake in the dark, she refuses to go to bed at night, or climbs into her parents' bed in the middle of the night despite warnings against doing so. She may also experience nightmares and insomnia, which further compound the problem. On the other hand, if her parents recognize that she is entering a phase in which nighttime fears are common, they can be prepared to provide her with extra measures of comfort and security so that she quickly accepts that "there's not really a monster under my bed" and "outgrows" her fears.

Clearly, the way that the child's parents handle her developmental challenges is an important factor in determining her future development. Although physicians have always known that this was true, we have only recently learned that this is because the child's brain is "plastic," or malleable, and is molded by tnany things, including her experiences. Scientific experiments have proven that the actual size and structure of the brain can be altered by factors in the environment; some experiences, such as practicing the piano or reciting poetry, result in improved brain function, while others, like drug and alcohol use, can dramatically decrease the child's potential capabilities.

The visual system is a good example of the brain's plasticity. When a child is born, her vision is limited to blurry images and indistinct colors, but it quickly comes into sharp focus as her brain is matured by the act of "seeing." The act of processing visual images causes some nerve connections to be strengthened and others to be eliminated. This shaping process is so important that it can make the difference between perfect vision and blindness. For example, if a child is born with cataracts, her brain doesn't receive any visual input and she's "blind." If the cataracts are removed soon after birth, she will have normal vision. But if the cataracts aren't removed until the shaping process is complete (sometime before the age of four), the child will always be blind--even though her eyes are now completely normal. She can't see because her brain hasn't learned how to process the images. The visual system is an unusually dramatic example of the plasticity of the brain, and there are no similar "all or none" periods during a child's emotional development. But since early experiences have such a tremendous impact on development, it is clear that a child's behavior problems are never something to be ignored.

The chapters in part I of Is It "Just a Phase"? provide parents with strategies for helping their children cope with a variety of common developmental problems, from hyperactivity, picky eating, naughtiness, and impulsivity, to shyness, excessive fears, sadness, and social isolation. A "real life" example, similar to Amy's story, introduces each chapter. These case histories are not based on any one child (in order to protect our patients' privacy), but are composites of our experience and training. The purpose of the stories is to give you a sense of the types of problems that fall under the category of "normal" childhood behavior. A case example of a "problem" behavior is also included so that you can decide which pattern is more similar to your child's behavior. If your child's behavior is in the normal range, suggestions are provided for helping her outgrow the problem, including ways in which you, your child's teacher, and her doctor can be of assistance. If your child's behavior appears more like one of the problem behaviors that are described, then you will be referted to the appropriate chapter in the second half of the book.

The second part of Is It "Just a Phase"? focuses on the symptoms of childhood psychiatric disorders--"problem behaviors," like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In addition to a case illustration, parents are provided with a diagnostic checklist so that they can accurately assess the nature and severity of their child's symptoms. Treatment strategies are presented and rated for safety and effectiveness. Suggestions are also provided for ways in which parents can help their child continue to grow and develop appropriately, even as she is recovering from the disorder.

It should be apparent by now that there is no shame or blame in this book. The problems described here can't be blamed on either the child or her parent, and neither of them should be ashamed when they occur. Difficult phases result when developmental challenges facing the child overcome her ability to cope, just as diabetes occurs when the blood sugar content exceeds the body's ability to make insulin. Psychiatric disorders occur when the brain malfunctions--they are medical illnesses, not a punishment for a child's weak character or a parent's mistakes.

Stomach ulcers provide the perfect analogy for our changing attitude toward mental illness. For generations, doctors thought that ulcers were brought on by stress and dietary indiscretions and patients were encouraged to "take it easy and avoid spicy foods." With that prescription, some of the patients got better, just as some patients with depression or anxiety disorders get better with rest and tender, loving care. Some ulcer patients' symptoms continued to worsen on the bland diet, however--not a surprise since the treatment failed to address the cause of the symptoms. A few years ago, an Australian doctor discovered that most ulcers are the result of a bacterial infection and, since then, antibiotics have become the treatment of choice--now 95 percent of the patients improve in the first six weeks. We haven't yet found the cause of most children's psychiatric disorders, so a true "cure" isn't immediately available, but important discoveries are being made every day. Recently, for example, researchers from the National Institute of Mental Health reported that some behavior problems may be caused by strep throat infections. If so, these disorders could be "cured" by immunologic treatments and possibly prevented by long-term penicillin treatment (see chapter 17 for a complete description).

It is our fervent hope that the cause and cure of children's psychiatric disorders are nearly at hand, and that our understanding of childhood development improves to the point at which we can prevent problem phases through early interventions by parents, physicians, and teachers. Until then, it is reassuring to know that these problems are real, they can be diagnosed accurately, and they will improve when given proper care and attention. The same holds true for undesirable developmental behaviors deemed normal, for no matter what the behavior problem, it's never "just a phase" that should be ignored.