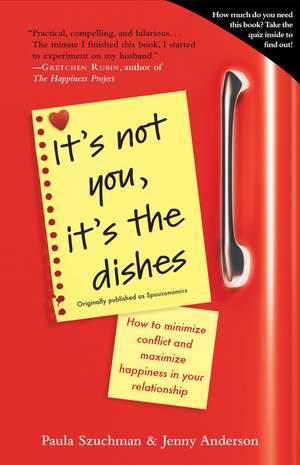

It's Not You, It's the Dishes (Originally Published as Spousonomics): How to Minimize Conflict and Maximize Happiness in Your Relationship

Autor Paula Szuchman, Jenny Andersonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2012

Originally published as Spousonomics

Preț: 97.74 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.70€ • 19.100$ • 15.59£

18.70€ • 19.100$ • 15.59£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385343954

ISBN-10: 0385343957

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: PHOTOS, CHARTS, GRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0385343957

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: PHOTOS, CHARTS, GRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Paula Szuchman is a page-one editor at The Wall Street Journal, where she was previously a reporter covering the travel industry, college internships, and roller coasters. She lives with her husband and daughter in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Jenny Anderson is a New York Times reporter who spent years covering Wall Street and won a Gerald Loeb Award for her coverage of Merrill Lynch. She currently writes on education and lives with her husband and daughter in Manhattan.

From the Hardcover edition.

Jenny Anderson is a New York Times reporter who spent years covering Wall Street and won a Gerald Loeb Award for her coverage of Merrill Lynch. She currently writes on education and lives with her husband and daughter in Manhattan.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Division of Labor

Or, Why You Should Do the Dishes

The Principle, Part One

Who should do what?

It’s one of the first questions Fortune 500 companies, governments, and gas stations have to answer if they plan on getting anything accomplished.

Consider your local Hess station. It wouldn’t exist without the truck drivers who delivered the concrete that was then poured and shaped into a foundation by a team of construction workers—not to be confused with the other team of construction workers who built the quickie mart, which is now staffed by a cashier in a green vest who sells the Ho Hos that were brought by the Hostess man with the “FBI: Female Body Inspector” T-shirt. There’s the guy who fills the underground tanks with gas, and the guy who pumps that gas into your car. Don’t forget the crane operator who lifts the number changer high up to the glowing Hess sign to swap out the number 7 next to “Premium” for a number 8 so that when you drive up, you can decide whether you want to spend $3.08 for a gallon of top-notch petroleum.

Every person has his or her job to do in order to create the final product: a functioning—and, if Hess is lucky, a prosperous—gas station. The fuel-pumping guy can’t drop his hose and start delivering fuel, just as the number changer can’t operate the crane without risking tearing a giant hole in the roof of the quickie mart, where the cashier sits, printing out lotto tickets and offering customers directions to the nearest IHOP.

This is what’s called “division of labor,” and it’s what makes econ?omies function.

Take a look around you. Every piece of furniture in your house, the boneless chicken breasts you eat for dinner, the car you drive, and the clothes on your back—they all owe their existence to a division of labor. Even the book you have in your hands right now came into being thanks to loggers, ink makers, printing press operators, glue producers, art directors, nagging editors, gifted writers, guys in suits who sign checks, and a group of deep-pocketed German publishers who pay the salaries of the suit-wearing check signers. There’s no way those gifted writers could fell a tree or pay anyone’s salary, much less their own. And maybe the ink makers could one day learn the art of glue producing, but it wouldn’t happen overnight, and the glue quality would probably never be the same, and . . . well, you get the idea.

That businesses thrive when employees have specialized tasks is hardly a novel idea. It probably dates back to the cavemen, when certain hunters were prized for their good aim and others were aces at skinning and filleting bison. But in more recent times, the concept is often credited to Adam Smith, the father of modern economics.

In 1776, Smith published his now seminal work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Among the many insights that to this day form the basis of economic theory, Smith argued that the secret to a nation’s wealth wasn’t money, but labor, and specifically, a division of labor based on specialization.

To prove his point, he used the example of a pin factory, saying that many more pins could be made in a day if each of eighteen specialized pin-making tasks was assigned to specific workers, rather than each worker making an entire pin from start to finish. Ten workers, he said, could produce forty-eight thousand pins a day if they specialized, versus perhaps just ten pins without specialization: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head.” And so on.

Seems evident now, at a time when many of us take specialization for granted, when we buy iPods in Kansas that were assembled in China with parts made in Japan and the Philippines, when we work in offices where some people are in charge of hanging art on the walls and others unclog toilets. But until Adam Smith put quill to parchment, no one had quite articulated the benefits of dividing labor into its component parts or made such a compelling argument for running the world this way.

The Principle, Part Two

Now back to the question of who should do what. Division of labor is only part of the answer. It tells us that no one person should do everything and that each person should have a specialty. But it doesn’t say anything about how we go about deciding who’s best suited to hanging art or pumping gas, or which country should make the iPod’s display screen and which the hard drive. For some ideas on that front, we turn to British economist David Ricardo, who, four decades after Smith’s Wealth of Nations, came up with a theory called “comparative advantage.”

The theory of comparative advantage says that it’s not efficient for you to take on every single task you’re good at, only on those tasks you’re relatively better at compared with other tasks. (See: Michael Jordan’s short-lived baseball career.) Or, as economists would put it, what matters is not your absolute ability to produce goods, but your ability to produce one good relative to another. Those are the things in which you have the comparative advantage.

Comparative advantage is the foundation of free trade. The idea is that instead of each country making everything it needs for its people, it should specialize in what it produces relatively better and then trade these goods and services with other countries. Countries develop specializations for any number of reasons. They might have control over scarce resources, like Saudi Arabia with oil. They might have millions of people willing to make flat-screen TVs for a pittance, as China does. They might have unique weather patterns, as Spain does, with its windy plains and burgeoning wind-turbine industry. Or they might be in the middle of nowhere: New Zealand, for example, saw a spike in tourism after the September 11 attacks, when travelers were looking for destinations terrorists would never think to go.

For David Ricardo, sitting in his Gloucestershire estate and ruminating on the notion of comparative advantage back in 1817, wind turbines and flat-screen TVs were the stuff of science fiction. Ricardo’s theory was founded on the much more rustic example of En?gland and Portugal trading wine and cloth. Ricardo said that even if Portugal could make both wine and cloth more quickly than En?gland could, it was still in Portugal’s interest to specialize in the one good it was relatively better at and trade with En?gland for the other.

Pay attention, because we’re going to tell you exactly how and why it pays to trade. First, take a look at the (hypothetical) amount of time it takes En?gland and Portugal to produce one unit each of wine and knickers (cloth) when they do it all themselves and don’t trade.

Without Trade

Product Portugal ?En?gland

1 pair of knickers 20 minutes 30 minutes

1 bottle of wine 10 minutes 60 minutes

Total time 30 minutes 90 minutes

Given how much faster Portugal is at making wine and knickers, you’d think Portugal should make everything itself, right? Wrong.

Here’s why:

Going it alone, Portugal spends half an hour making a bottle of wine and a pair of knickers and En?gland spends ninety minutes doing the same.

Let’s say they decide to trade. Portugal makes two bottles of wine, since it’s relatively faster at wine than at knicker making, what with all the grapes growing everywhere. En?gland makes two pairs of knickers, since it clearly has more sheep than vineyards. Then they trade—one pair of knickers for one bottle of wine . . . and suddenly Portugal’s got one of each for only twenty minutes of work. En?gland had to put in only sixty minutes of work instead of ninety.

With Trade

Product Portugal ?En?gland

2 pairs of knickers n/a 60 minutes

2 bottles of wine 20 minutes n/a

Total time after trade 20 minutes 60 minutes

It’s like magic. Only it’s not magic. It’s math. Very, very simple math, we concede—math that doesn’t take into account all the other things the two countries make or the prices they could charge for their goods on the open market. It’s also true that En?gland’s workers still wind up working longer hours compared with Portugal’s workers for the same rewards, but it’s undeniable that they’ve saved time relative to their pretrading workloads.

Ricardo’s model illustrates a universal truth: There are great rewards to be had from trading smartly and great wastes of time and energy from trying to do everything yourself, or even from splitting things in half.

Which is what takes us to the topic you’ve probably been waiting for: your marriage. Think of your marriage as a business comprising two partners. You’re not only business partners in the sense that you work together for the good of your company, you’re also trading partners who exchange services, often in the form of household chores. How should you decide who does what? Who should specialize in shopping for orange juice and who in cleaning windows? Who should provide clothes that are freshly laundered and folded, and who should put food on the table at dinnertime? We all wish these kinds of questions had easy answers, yet household labor issues are often the most divisive that couples face. They don’t have to be. Economics offers clear solutions. You’re about to meet three couples, each of whom were nearly undone by all sorts of seemingly inane duties that they were dividing in all the wrong ways.

One couple, thinking that a fifty/fifty split was the way to go, made the mistake of having no specializations at all. Another couple miscalculated what their comparative advantages were, and a third couple discovered that specializations aren’t static and can sometimes change as the marriage itself changes.

Case Study #1

The Players: Eric and Nancy

Eric and Nancy had never heard of David Ricardo when they fell in love and decided to merge as lifelong trading partners. They weren’t familiar with the theory of comparative advantage, and if it came up at a dinner party—which, frankly, it never did—their eyes would very likely have glazed over. Eric was a photographer for glossy cooking magazines, and Nancy designed a line of teen clothing for one of those apparel chains that have an outpost at every mall in America. They were more artsy than economicsy.

Yet economics—bad economics—dominated their lives. Without knowing it, they’d become a case study in how a bad division of labor can harm an otherwise well-matched couple. That’s because Eric and Nancy split the work not on the basis of who did which job best, but on what seemed fair. And fair, in their view, was a strict fifty/fifty split.

They divided everything in half. They had a joint checking account into which their roughly equivalent salaries were deposited directly and from which they transferred the same allowances every month into their individual checking accounts to spend as they pleased. They had a mutt named Moo Shoo whom they took turns walking every other morning. When Eric cooked, Nancy cleaned. When Nancy cooked, Eric cleaned. They rotated laundry, bill paying, in-law calling, trash days. Eric was in charge of cleaning the upstairs bathroom. Nancy handled the downstairs.

On the outside, Eric and Nancy’s system made them seem like the perfect modern couple. Their friends marveled at how they defied stereotypes: Eric knows how to use a Swiffer! Nancy gives him so much space! He’s so accommodating! She goes to Home Depot without him!

There was only one kink: Eric and Nancy weren’t happy.

The Problem: The Fifty/Fifty Marriage

Here’s a puzzler: Think of a successful business whose employees work the exact same hours and do the exact same amount of work for the exact same pay.

Still thinking?

That’s because, outside of assembly lines, there aren’t many.

From your grocery store to your money manager’s office to the website you get your news from, businesses are organized around specialization. Employees have distinct tasks that require different sorts of expertise and command higher or lower salaries. Bond traders know the bond market inside and out, stock traders are more proficient in stocks. There are people who sell the ads that appear on The Wall Street Journal’s website and people who write the stories, and neither group knows very much about what the other does all day.

Imagine what would happen if those ad guys started spending half their time writing articles and reporters spent half their time selling ads—all in the name of fairness. It would be a disaster.

The specialization model also applies to the broader economy. Some countries grow bananas, some produce cars, some make tank tops.

The same logic applies to marriage. In insisting on a “fair” division of labor, Eric and Nancy had created a monster. For all their focus on fifty/fifty, some days things could feel a little too egalitarian.

Like when the laundry hamper would overflow with dirty clothes and an exhausted Nancy would say to Eric, who was busy shopping for old camera equipment online, “I did the laundry last time—it’s your turn.”

Or when Eric, chopping onions for a lamb tagine, saw Nancy watching Law & Order and thought, “Wait a minute, why am I spending all this time on a fancy meal when all she ever makes is mac and cheese?”

Or the time Nancy’s parents were coming for dinner and she and Eric spent the day arguing over whether Eric cleaning his office really counted as “housework” as much as Nancy mopping all the floors—since, said Nancy, his office wasn’t a “communal living area.”

This was life at Eric and Nancy’s house. Each one constantly monitoring the other’s workload, keeping mental bar graphs of who had done more and who had fallen behind, sounding the unfairness alarm whenever it seemed the split was starting to shift into the—gasp!—sixty/forty range. “Everything was a debate,” said Nancy. “We spent so much time fighting over who was doing more and who needed to pick up the slack, it’s amazing we got anything done at

all.”

“It got to the point where if I was dusting and Nancy was painting her nails, I’d drop the duster and check my email just so I didn’t end up doing more than her,” said Eric.

They posted two chore logs outside the kitchen and checked them frequently to ensure no one was cutting corners.

As you can see in the “basic chore log” below created by Nancy, even opening the mail counted as a chore. In fact, once Nancy realized how much time she was spending on the mail, she decided it was only fair to hand off making the bed to Eric.

Not to be outdone, Eric created an “advanced chore log” that included onetime jobs. These tended to be more time-consuming and intensive. Eric thought he was being especially clever when he delineated his tasks into “easy,” “harder,” and “pain in the butt,” lest Nancy think that he was getting away with all the simple stuff.

Division of Labor

Or, Why You Should Do the Dishes

The Principle, Part One

Who should do what?

It’s one of the first questions Fortune 500 companies, governments, and gas stations have to answer if they plan on getting anything accomplished.

Consider your local Hess station. It wouldn’t exist without the truck drivers who delivered the concrete that was then poured and shaped into a foundation by a team of construction workers—not to be confused with the other team of construction workers who built the quickie mart, which is now staffed by a cashier in a green vest who sells the Ho Hos that were brought by the Hostess man with the “FBI: Female Body Inspector” T-shirt. There’s the guy who fills the underground tanks with gas, and the guy who pumps that gas into your car. Don’t forget the crane operator who lifts the number changer high up to the glowing Hess sign to swap out the number 7 next to “Premium” for a number 8 so that when you drive up, you can decide whether you want to spend $3.08 for a gallon of top-notch petroleum.

Every person has his or her job to do in order to create the final product: a functioning—and, if Hess is lucky, a prosperous—gas station. The fuel-pumping guy can’t drop his hose and start delivering fuel, just as the number changer can’t operate the crane without risking tearing a giant hole in the roof of the quickie mart, where the cashier sits, printing out lotto tickets and offering customers directions to the nearest IHOP.

This is what’s called “division of labor,” and it’s what makes econ?omies function.

Take a look around you. Every piece of furniture in your house, the boneless chicken breasts you eat for dinner, the car you drive, and the clothes on your back—they all owe their existence to a division of labor. Even the book you have in your hands right now came into being thanks to loggers, ink makers, printing press operators, glue producers, art directors, nagging editors, gifted writers, guys in suits who sign checks, and a group of deep-pocketed German publishers who pay the salaries of the suit-wearing check signers. There’s no way those gifted writers could fell a tree or pay anyone’s salary, much less their own. And maybe the ink makers could one day learn the art of glue producing, but it wouldn’t happen overnight, and the glue quality would probably never be the same, and . . . well, you get the idea.

That businesses thrive when employees have specialized tasks is hardly a novel idea. It probably dates back to the cavemen, when certain hunters were prized for their good aim and others were aces at skinning and filleting bison. But in more recent times, the concept is often credited to Adam Smith, the father of modern economics.

In 1776, Smith published his now seminal work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Among the many insights that to this day form the basis of economic theory, Smith argued that the secret to a nation’s wealth wasn’t money, but labor, and specifically, a division of labor based on specialization.

To prove his point, he used the example of a pin factory, saying that many more pins could be made in a day if each of eighteen specialized pin-making tasks was assigned to specific workers, rather than each worker making an entire pin from start to finish. Ten workers, he said, could produce forty-eight thousand pins a day if they specialized, versus perhaps just ten pins without specialization: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head.” And so on.

Seems evident now, at a time when many of us take specialization for granted, when we buy iPods in Kansas that were assembled in China with parts made in Japan and the Philippines, when we work in offices where some people are in charge of hanging art on the walls and others unclog toilets. But until Adam Smith put quill to parchment, no one had quite articulated the benefits of dividing labor into its component parts or made such a compelling argument for running the world this way.

The Principle, Part Two

Now back to the question of who should do what. Division of labor is only part of the answer. It tells us that no one person should do everything and that each person should have a specialty. But it doesn’t say anything about how we go about deciding who’s best suited to hanging art or pumping gas, or which country should make the iPod’s display screen and which the hard drive. For some ideas on that front, we turn to British economist David Ricardo, who, four decades after Smith’s Wealth of Nations, came up with a theory called “comparative advantage.”

The theory of comparative advantage says that it’s not efficient for you to take on every single task you’re good at, only on those tasks you’re relatively better at compared with other tasks. (See: Michael Jordan’s short-lived baseball career.) Or, as economists would put it, what matters is not your absolute ability to produce goods, but your ability to produce one good relative to another. Those are the things in which you have the comparative advantage.

Comparative advantage is the foundation of free trade. The idea is that instead of each country making everything it needs for its people, it should specialize in what it produces relatively better and then trade these goods and services with other countries. Countries develop specializations for any number of reasons. They might have control over scarce resources, like Saudi Arabia with oil. They might have millions of people willing to make flat-screen TVs for a pittance, as China does. They might have unique weather patterns, as Spain does, with its windy plains and burgeoning wind-turbine industry. Or they might be in the middle of nowhere: New Zealand, for example, saw a spike in tourism after the September 11 attacks, when travelers were looking for destinations terrorists would never think to go.

For David Ricardo, sitting in his Gloucestershire estate and ruminating on the notion of comparative advantage back in 1817, wind turbines and flat-screen TVs were the stuff of science fiction. Ricardo’s theory was founded on the much more rustic example of En?gland and Portugal trading wine and cloth. Ricardo said that even if Portugal could make both wine and cloth more quickly than En?gland could, it was still in Portugal’s interest to specialize in the one good it was relatively better at and trade with En?gland for the other.

Pay attention, because we’re going to tell you exactly how and why it pays to trade. First, take a look at the (hypothetical) amount of time it takes En?gland and Portugal to produce one unit each of wine and knickers (cloth) when they do it all themselves and don’t trade.

Without Trade

Product Portugal ?En?gland

1 pair of knickers 20 minutes 30 minutes

1 bottle of wine 10 minutes 60 minutes

Total time 30 minutes 90 minutes

Given how much faster Portugal is at making wine and knickers, you’d think Portugal should make everything itself, right? Wrong.

Here’s why:

Going it alone, Portugal spends half an hour making a bottle of wine and a pair of knickers and En?gland spends ninety minutes doing the same.

Let’s say they decide to trade. Portugal makes two bottles of wine, since it’s relatively faster at wine than at knicker making, what with all the grapes growing everywhere. En?gland makes two pairs of knickers, since it clearly has more sheep than vineyards. Then they trade—one pair of knickers for one bottle of wine . . . and suddenly Portugal’s got one of each for only twenty minutes of work. En?gland had to put in only sixty minutes of work instead of ninety.

With Trade

Product Portugal ?En?gland

2 pairs of knickers n/a 60 minutes

2 bottles of wine 20 minutes n/a

Total time after trade 20 minutes 60 minutes

It’s like magic. Only it’s not magic. It’s math. Very, very simple math, we concede—math that doesn’t take into account all the other things the two countries make or the prices they could charge for their goods on the open market. It’s also true that En?gland’s workers still wind up working longer hours compared with Portugal’s workers for the same rewards, but it’s undeniable that they’ve saved time relative to their pretrading workloads.

Ricardo’s model illustrates a universal truth: There are great rewards to be had from trading smartly and great wastes of time and energy from trying to do everything yourself, or even from splitting things in half.

Which is what takes us to the topic you’ve probably been waiting for: your marriage. Think of your marriage as a business comprising two partners. You’re not only business partners in the sense that you work together for the good of your company, you’re also trading partners who exchange services, often in the form of household chores. How should you decide who does what? Who should specialize in shopping for orange juice and who in cleaning windows? Who should provide clothes that are freshly laundered and folded, and who should put food on the table at dinnertime? We all wish these kinds of questions had easy answers, yet household labor issues are often the most divisive that couples face. They don’t have to be. Economics offers clear solutions. You’re about to meet three couples, each of whom were nearly undone by all sorts of seemingly inane duties that they were dividing in all the wrong ways.

One couple, thinking that a fifty/fifty split was the way to go, made the mistake of having no specializations at all. Another couple miscalculated what their comparative advantages were, and a third couple discovered that specializations aren’t static and can sometimes change as the marriage itself changes.

Case Study #1

The Players: Eric and Nancy

Eric and Nancy had never heard of David Ricardo when they fell in love and decided to merge as lifelong trading partners. They weren’t familiar with the theory of comparative advantage, and if it came up at a dinner party—which, frankly, it never did—their eyes would very likely have glazed over. Eric was a photographer for glossy cooking magazines, and Nancy designed a line of teen clothing for one of those apparel chains that have an outpost at every mall in America. They were more artsy than economicsy.

Yet economics—bad economics—dominated their lives. Without knowing it, they’d become a case study in how a bad division of labor can harm an otherwise well-matched couple. That’s because Eric and Nancy split the work not on the basis of who did which job best, but on what seemed fair. And fair, in their view, was a strict fifty/fifty split.

They divided everything in half. They had a joint checking account into which their roughly equivalent salaries were deposited directly and from which they transferred the same allowances every month into their individual checking accounts to spend as they pleased. They had a mutt named Moo Shoo whom they took turns walking every other morning. When Eric cooked, Nancy cleaned. When Nancy cooked, Eric cleaned. They rotated laundry, bill paying, in-law calling, trash days. Eric was in charge of cleaning the upstairs bathroom. Nancy handled the downstairs.

On the outside, Eric and Nancy’s system made them seem like the perfect modern couple. Their friends marveled at how they defied stereotypes: Eric knows how to use a Swiffer! Nancy gives him so much space! He’s so accommodating! She goes to Home Depot without him!

There was only one kink: Eric and Nancy weren’t happy.

The Problem: The Fifty/Fifty Marriage

Here’s a puzzler: Think of a successful business whose employees work the exact same hours and do the exact same amount of work for the exact same pay.

Still thinking?

That’s because, outside of assembly lines, there aren’t many.

From your grocery store to your money manager’s office to the website you get your news from, businesses are organized around specialization. Employees have distinct tasks that require different sorts of expertise and command higher or lower salaries. Bond traders know the bond market inside and out, stock traders are more proficient in stocks. There are people who sell the ads that appear on The Wall Street Journal’s website and people who write the stories, and neither group knows very much about what the other does all day.

Imagine what would happen if those ad guys started spending half their time writing articles and reporters spent half their time selling ads—all in the name of fairness. It would be a disaster.

The specialization model also applies to the broader economy. Some countries grow bananas, some produce cars, some make tank tops.

The same logic applies to marriage. In insisting on a “fair” division of labor, Eric and Nancy had created a monster. For all their focus on fifty/fifty, some days things could feel a little too egalitarian.

Like when the laundry hamper would overflow with dirty clothes and an exhausted Nancy would say to Eric, who was busy shopping for old camera equipment online, “I did the laundry last time—it’s your turn.”

Or when Eric, chopping onions for a lamb tagine, saw Nancy watching Law & Order and thought, “Wait a minute, why am I spending all this time on a fancy meal when all she ever makes is mac and cheese?”

Or the time Nancy’s parents were coming for dinner and she and Eric spent the day arguing over whether Eric cleaning his office really counted as “housework” as much as Nancy mopping all the floors—since, said Nancy, his office wasn’t a “communal living area.”

This was life at Eric and Nancy’s house. Each one constantly monitoring the other’s workload, keeping mental bar graphs of who had done more and who had fallen behind, sounding the unfairness alarm whenever it seemed the split was starting to shift into the—gasp!—sixty/forty range. “Everything was a debate,” said Nancy. “We spent so much time fighting over who was doing more and who needed to pick up the slack, it’s amazing we got anything done at

all.”

“It got to the point where if I was dusting and Nancy was painting her nails, I’d drop the duster and check my email just so I didn’t end up doing more than her,” said Eric.

They posted two chore logs outside the kitchen and checked them frequently to ensure no one was cutting corners.

As you can see in the “basic chore log” below created by Nancy, even opening the mail counted as a chore. In fact, once Nancy realized how much time she was spending on the mail, she decided it was only fair to hand off making the bed to Eric.

Not to be outdone, Eric created an “advanced chore log” that included onetime jobs. These tended to be more time-consuming and intensive. Eric thought he was being especially clever when he delineated his tasks into “easy,” “harder,” and “pain in the butt,” lest Nancy think that he was getting away with all the simple stuff.

Recenzii

“One of the most delightful, clever, and helpful books about marriage I’ve ever seen.”—Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love

“Practical, compelling, and hilarious . . . The minute I finished this book, I started to experiment on my husband.”—Gretchen Rubin, author of The Happiness Project

“This clever and hilarious book is really a user’s manual for improving relationships in marriage, family, business, and society in general.”—The Miami Herald

“The book is grounded in solid research, makes economics entertaining, and might just save a marriage or two.”—James Pressley, Bloomberg

“A convincing and creative case for how the dismal science can help reconcile marital disputes.”—The Washington Post

“Practical, compelling, and hilarious . . . The minute I finished this book, I started to experiment on my husband.”—Gretchen Rubin, author of The Happiness Project

“This clever and hilarious book is really a user’s manual for improving relationships in marriage, family, business, and society in general.”—The Miami Herald

“The book is grounded in solid research, makes economics entertaining, and might just save a marriage or two.”—James Pressley, Bloomberg

“A convincing and creative case for how the dismal science can help reconcile marital disputes.”—The Washington Post

Descriere

Marriage can be a mysterious, often irrational business. But the key, propose Szuchman and Anderson in this incomparable and engaging book, is to think like an economist. There is limited time, money, and energy, but we must allocate these resources efficiently.