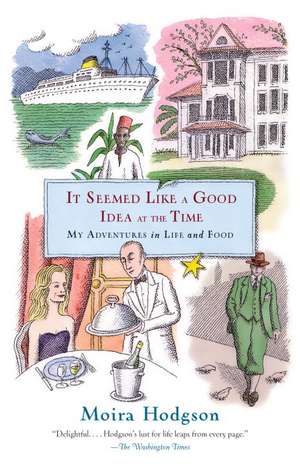

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: My Adventures in Life and Food

Autor Moira Hodgsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

A delightful memoir of meals from around the world—complete with recipes—It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time reflects Hodgson’s talent for connecting her love of food and travel with the people and places in her life. Whether she’s dining on Moroccan mechoui, a whole lamb baked for a day over coals, or struggling to entertain in a tiny Greenwich Village apartment, her reminiscences are always a treat.

Preț: 111.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.33€ • 23.17$ • 17.93£

21.33€ • 23.17$ • 17.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767912716

ISBN-10: 0767912713

Pagini: 334

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOS AND RECIPES

Dimensiuni: 141 x 202 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0767912713

Pagini: 334

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOS AND RECIPES

Dimensiuni: 141 x 202 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Moira Hodgson was the restaurant critic for the New York Observer for two decades. She has worked on the staff of the New York Times and Vanity Fair, and is the author of several cookbooks. She lives in New York City and Connecticut.

Extras

THE WAITER STOOD OVER ME, pen at the ready. "Signorina?"

For lunch I ordered sardines on toast, pickled herring, a grilled mutton chop, buttered green beans, pommes lyonnaise and lemon sherbet.

I was twelve, sitting with my family in the dining room of Lloyd Triestino's MV Victoria as we sailed through the Strait of Malacca, en route from Singapore to Genoa. Once again, we had packed up and were moving on. Those were the days of the great ocean liners, and my first meals out were not in restaurants, but on ships.

A color reproduction of an eighteenth-century Italian Romantic painting decorated the cover of the menu. It told a story. A young woman with downcast eyes hastened across a balcony in Venice, a black veil artfully draped over her hair and shoulders to reveal her pale, comely face and low decolletage. She was holding a letter behind her as if it contained some news she couldn't bear to read. The title of the picture was Vendetta, which a translator had rendered, insipidly, "Requital."

The long menu was in Italian, with an English translation on the opposite page. The words had a dramatic poetry that made my imagination soar: "jellied goose liver froth . . . Moscovite canape . . . glazed veal muscle Æ la Milanese . . . savage orange duck . . . golden supreme of swallow fish in butter . . ." And darkly: "slice of liver English-style." Because the ship docked in Bombay, Karachi and Colombo, there was also Indian food, a curry of the day described only by a town or region--Goa, Madras, Delhi--served with things I'd never heard of--pappadom, chapatti, paratha, dal and biriani.

For the next three weeks, the menu changed every lunch and dinner, with a different Italian Romantic painting on its cover (always a portrait of a beautiful woman; this was an Italian ship, after all).

I ticked off the dishes I ate and pasted the menus into a blue scrapbook. I am looking at it now. It opens with a display of black-and-white postcards of the long, elegant white ship, built in 1951, so different from the bloated shape of today's cruise liners. A Lloyd Triestino paper napkin signed with the names of the seven young members of the Seasick Sea Serpents Club, founded by yours truly, shares a page with a yellow matchbook stamped in red with the steamship company's far-flung continents of call: Asia, Africa and Australia. The passenger list erroneously records the family as embarking in Karachi. A brochure of useful hints advises "easy dress" for lunch and "formal attire" for dinner. The programs for the day's activities, slipped under the cabin door each morning, are also pasted onto my book's faded, dog-eared pages, their covers printed with commedia dell'arte figures: Pierrot, Columbine, Harlequin and clowns, one of them with a red nose, holding out a tumbler of wine. There were concerts by the ship's orchestra (as many as four a day), fancy dress balls and bartender Carlo's special cocktails, such as gin with lemon and green Chartreuse. I also glued in brochures of the places we visited when the ship docked in a port of call: a "luxury" coach tour of Bombay (where I saw vultures circling funeral pyres that burned behind high walls) and a sleepy Italian fishing village called Portofino "for people seeking rest and quiet." Pink and orange tickets to horsey horsey and tombola make a collage with the ship's airmail envelopes and its itinerary, illustrated with a red pagoda. But most of the pages of my scrapbook are taken up with menus.

Potatoes pont neuf were thick french fries. "Norcia pearls," served with Strasbourg sausage, were lentils. Rollmops were fillets of marinated herring wrapped around pickles. Hoppel poppel "in saucepan on toast" was a fry-up of onions, potatoes, pork and eggs. "Crusted pie Lucullus" turned out to be a pate laced with chunks of foie gras; chicken quenelles were dumplings, flecked with black truffles; "golden reserve" pheasant in voliere [sic] arrived in a sauce made with "fine" Champagne. Chicken cream soup "Agnes Sorel" was named for the mistress of the French king Charles XII who died suddenly at the age of twenty-eight, thought to have been poisoned. A strange name for a soup.

I was allowed to order whatever I wanted as long as I had a "properly balanced meal." The food arrived under a silver dome that was whisked off by the waiter with an operatic flourish (and not without a touch of irony) to reveal my choice du jour with its two requisite vegetables: potatoes always (available in more than two dozen ways, from "Hungarian cream" to "Castle-style," roasted with rosemary), and often, curiously, stewed red cabbage. I was even permitted half a glass of wine.

"Hai una buona forchetta!" the waiter would say, setting down my lunch of chateaubriand with mashed potatoes and Parmesan cauliflower, or cannelloni with a side order of peas. "You have a good appetite." The translator of our menus would have said, "You have a good fork."

I was tall for my age and rail thin. But I ate for two.

What were those meals really like? Would they impress me now, after years of dining out in restaurants, most often as a critic?

Those three weeks on the Victoria, eating whatever exotic dish struck my fancy, left a lifelong imprint. They were the first step to loving good food. Meals were an occasion. We bathed and changed for dinner. My father wore a tropical-weight dinner jacket, my mother one of the copies of Paris fashions she'd had made by a dressmaker in Saigon.

I bounded up the stairs when the gong sounded for the first sitting, my little sister, Philippa, in hot pursuit, hoping she'd be allowed spaghetti and meatballs yet again. I wanted to try everything. I wished I could always eat like this, in the dining rooms of ocean liners, sailing between continents, with a ravenous appetite brought on by the sea air, wondering whether today I should order Stewed Veal "Stanley" or take a chance on the cold table's Blown Poularde "Rose of May."

MY PARENTS BELONGED TO a hierarchical and class-conscious generation. Keeping up appearances was a nerve-racking job, and nowhere was that more evident than in the British Army and the diplomatic corps.

"I feel wrong," my mother, Lyla, would often say as she stood in front of the mirror, putting on her long gloves and patting her hair in exasperation. It was a refrain I heard throughout her life. Her forehead was too high. Her curly auburn hair was too thin, her pale skin too fine and prone to wrinkles.

There was nothing wrong with her looks. My mother was a beauty. But behind the glamorous facade, she was often frightened, as if some catastrophe were about to take place and she was helpless to prevent it.

It wasn't the travel, the upheaval involved in changing countries every two years that made my mother so often feel "wrong." It was lack of money, insecurity, the rigid British class system. She was acutely aware of rank, of who was a third secretary or a counselor in the embassy, who sat "below the salt," who was placed to the left and the right of the host and hostess of a dinner party. She pronounced the word brassiere to rhyme with sassier, and flinched at the lower-middle-class words toilet, lounge (unless in a hotel or an airport) and pardon? instead of what?

She had a high upper-middle-class English voice, but her parents were Scots Irish who'd left Ulster for England in 1922 to get away from the Troubles. It was lucky that her mother had found a job as a science teacher at Sherborne School for Girls in Dorset. My grandfather, an engineer, spent much of his life either working in Africa, unemployed (during the Slump) or on sick leave, so the family scraped by.

Salaries in the diplomatic corps, moreover, were based on the assumption of a supplementary private income. Wives were not allowed to work. They were supposed to support their husbands by throwing dinners and cocktail parties, attending teas and luncheons, and knowing just enough French for the refrain, "Et combien d'enfants avez-vous, madame?"

Even food was about class distinction. The table betrayed everything. "Don't hold your knife like a pencil [lower middle class]. And don't spread your bread with butter all at once [working class]. Break off a small piece at a time [upper class]."

Working classes referred to lunch as "dinner" and dinner as "tea." Middle classes put the milk in first when they made a cup of tea. Working classes not only put the milk in first, they drank their tea at odd times of day.

Even the innocent question "What's for pudding?"--the first thing you'd ask when you sat down at the table--revealed what class you came from. The upper-class word for dessert was pudding. Lower-middle classes said sweet.

My father, Philip, didn't give a damn about any of it.

My parents were students at Cambridge when they met in 1939, the year Britain declared war on Germany. My mother read science, a subject forced upon her by my grandmother. She hated it ("I'd rather have read a book"), and went to too many parties. My father, who was on full scholarship, read modern and medieval languages. They were nothing more than friends.

After my father got his degree in 1943, he went to Sandhurst to train as an army officer. My mother tested bombs at the Royal Air Force base in Farnborough in Hampshire. She went up in a "harrier," a propeller-driven airplane with an open cockpit, and dropped dummy bombs, noting the angle of their fall.

In Farnborough, one of the officers took her out for a drink at a local pub and regaled her with tales of his dangerous flights. After lighting cigarettes for the two of them, he tossed the matchbox onto the floor.

"And there," he said, pointing down at the matchbox, "was the aircraft carrier . . ."

When she told this story, my mother would drop a matchbox on the floor and I'd gaze down at it, feeling quite vertiginous. We'd laugh, but most of those pilots hadn't come back.

My parents ran into each other again in a restaurant in London when my father was on a winter leave from Sandhurst. One evening several months later they sat in the dark in his parents' flat, which looked out over Buckingham Palace, as Hitler's bombs dropped around them. He proposed and she accepted. It all happened very fast. On July 29, 1944, when they were barely twenty-three years old, they were married in Sherborne Abbey, Lyla in a long white dress and a veil and Philip, a captain in the First Airborne Division, in a brand-new military uniform.

My mother was already pregnant with me when, just over six weeks after the wedding, on September 17, my father was dropped at Arnhem, a small town on the lower Rhine River in Holland. Operation Market Garden, as it was called, was the largest airborne campaign ever launched (the subject of the novel and film A Bridge Too Far). Its purpose was to secure the bridges that were under German occupation and advance into the Ruhr. But the British were outnumbered and suffered a crushing defeat, failing to capture the bridge at Arnhem. As they retreated from the Germans, my father gave up his place in one of the boats to a wounded friend and swam across the Rhine. Only a quarter of his unit made it back.

In May, the month I was born, my father was part of the liberation of Norway, where he received a medal from King Haakon VII. The only thing he ever told me about that time was that in Oslo he'd met a twenty-four-year-old man who had been tortured so badly by the Gestapo his hair had gone completely white. My father then spent a year in Schleswig-Holstein, where there were camps for displaced persons, involved in "mopping up" operations, whatever that meant. Like all the men in our family who came back from the war, he maintained his silence. I knew terrible things had happened that he could not bring himself to tell, and I always wondered what they were.

My father was two months younger than my mother, six foot one and very good-looking, with dark brown eyes and straight brown hair. He was born in London, the youngest child of four by a decade. My mother said this had made him taciturn. "Nobody in that family talked except his mother, who never stopped."

His father worked at the Board of Trade and was knighted by the Queen for his services. Sir Edward, a wine connoisseur who played bowls in his spare time, died at the dinner table, age seventy-five, his arm raised in a toast. But Sir Edward had had no money. So my father was always short of it too.

On his eighth birthday, while on a family holiday in Keswick, he was given a bicycle. He rode it to a sweetshop, parked by the front door, and went in to buy a chocolate bar. When he came out a few minutes later, the bicycle was gone.

"That's too bad," said his parents. "Sorry, but there we are."

They never bought him another one.

My mother thought my father was cold because, although he liked to play the clown, he rarely revealed his emotions. She came from an Irish family where books were brought down from the shelves during dinner to prove a point, exchanges were volatile and confrontational, and meals regularly wound up with the slamming of doors or fists banging down on the table, often followed by a great deal of laughter.

With Philip there was much laughter too, but few exchanges of confidences, glimmers of vulnerability or unexpected revelations about his inner life, even after a few drinks.

"He never asked what I was thinking about, either," she said. "I thought he simply didn't care"

So they had a perfectly dreadful honeymoon in Torquay, where it rained the whole time.

It was years before she realized that he was chronically shy.

Thanks to my father's job, we led a privileged life way beyond my parents' means. The government paid for private schools, servants, nannies and even chauffeurs. Cigarettes and liquor were duty-free and there was no dearth of drink: Pimm's No. 1, laced with slivers of cucumber and sprigs of mint, pink gins served straight up in martini glasses with a drop of Angostura bitters, whisky and water (no ice), a decent bottle of claret, brandy, Calvados, Madeira, Poire William, framboise, port and a digestif popular with the American wives, creme de menthe.

But wherever we were, in England or abroad, there was English food at home for the children (and often for the grown-ups too). It was familiar, stable and safe.

From the Hardcover edition.

For lunch I ordered sardines on toast, pickled herring, a grilled mutton chop, buttered green beans, pommes lyonnaise and lemon sherbet.

I was twelve, sitting with my family in the dining room of Lloyd Triestino's MV Victoria as we sailed through the Strait of Malacca, en route from Singapore to Genoa. Once again, we had packed up and were moving on. Those were the days of the great ocean liners, and my first meals out were not in restaurants, but on ships.

A color reproduction of an eighteenth-century Italian Romantic painting decorated the cover of the menu. It told a story. A young woman with downcast eyes hastened across a balcony in Venice, a black veil artfully draped over her hair and shoulders to reveal her pale, comely face and low decolletage. She was holding a letter behind her as if it contained some news she couldn't bear to read. The title of the picture was Vendetta, which a translator had rendered, insipidly, "Requital."

The long menu was in Italian, with an English translation on the opposite page. The words had a dramatic poetry that made my imagination soar: "jellied goose liver froth . . . Moscovite canape . . . glazed veal muscle Æ la Milanese . . . savage orange duck . . . golden supreme of swallow fish in butter . . ." And darkly: "slice of liver English-style." Because the ship docked in Bombay, Karachi and Colombo, there was also Indian food, a curry of the day described only by a town or region--Goa, Madras, Delhi--served with things I'd never heard of--pappadom, chapatti, paratha, dal and biriani.

For the next three weeks, the menu changed every lunch and dinner, with a different Italian Romantic painting on its cover (always a portrait of a beautiful woman; this was an Italian ship, after all).

I ticked off the dishes I ate and pasted the menus into a blue scrapbook. I am looking at it now. It opens with a display of black-and-white postcards of the long, elegant white ship, built in 1951, so different from the bloated shape of today's cruise liners. A Lloyd Triestino paper napkin signed with the names of the seven young members of the Seasick Sea Serpents Club, founded by yours truly, shares a page with a yellow matchbook stamped in red with the steamship company's far-flung continents of call: Asia, Africa and Australia. The passenger list erroneously records the family as embarking in Karachi. A brochure of useful hints advises "easy dress" for lunch and "formal attire" for dinner. The programs for the day's activities, slipped under the cabin door each morning, are also pasted onto my book's faded, dog-eared pages, their covers printed with commedia dell'arte figures: Pierrot, Columbine, Harlequin and clowns, one of them with a red nose, holding out a tumbler of wine. There were concerts by the ship's orchestra (as many as four a day), fancy dress balls and bartender Carlo's special cocktails, such as gin with lemon and green Chartreuse. I also glued in brochures of the places we visited when the ship docked in a port of call: a "luxury" coach tour of Bombay (where I saw vultures circling funeral pyres that burned behind high walls) and a sleepy Italian fishing village called Portofino "for people seeking rest and quiet." Pink and orange tickets to horsey horsey and tombola make a collage with the ship's airmail envelopes and its itinerary, illustrated with a red pagoda. But most of the pages of my scrapbook are taken up with menus.

Potatoes pont neuf were thick french fries. "Norcia pearls," served with Strasbourg sausage, were lentils. Rollmops were fillets of marinated herring wrapped around pickles. Hoppel poppel "in saucepan on toast" was a fry-up of onions, potatoes, pork and eggs. "Crusted pie Lucullus" turned out to be a pate laced with chunks of foie gras; chicken quenelles were dumplings, flecked with black truffles; "golden reserve" pheasant in voliere [sic] arrived in a sauce made with "fine" Champagne. Chicken cream soup "Agnes Sorel" was named for the mistress of the French king Charles XII who died suddenly at the age of twenty-eight, thought to have been poisoned. A strange name for a soup.

I was allowed to order whatever I wanted as long as I had a "properly balanced meal." The food arrived under a silver dome that was whisked off by the waiter with an operatic flourish (and not without a touch of irony) to reveal my choice du jour with its two requisite vegetables: potatoes always (available in more than two dozen ways, from "Hungarian cream" to "Castle-style," roasted with rosemary), and often, curiously, stewed red cabbage. I was even permitted half a glass of wine.

"Hai una buona forchetta!" the waiter would say, setting down my lunch of chateaubriand with mashed potatoes and Parmesan cauliflower, or cannelloni with a side order of peas. "You have a good appetite." The translator of our menus would have said, "You have a good fork."

I was tall for my age and rail thin. But I ate for two.

What were those meals really like? Would they impress me now, after years of dining out in restaurants, most often as a critic?

Those three weeks on the Victoria, eating whatever exotic dish struck my fancy, left a lifelong imprint. They were the first step to loving good food. Meals were an occasion. We bathed and changed for dinner. My father wore a tropical-weight dinner jacket, my mother one of the copies of Paris fashions she'd had made by a dressmaker in Saigon.

I bounded up the stairs when the gong sounded for the first sitting, my little sister, Philippa, in hot pursuit, hoping she'd be allowed spaghetti and meatballs yet again. I wanted to try everything. I wished I could always eat like this, in the dining rooms of ocean liners, sailing between continents, with a ravenous appetite brought on by the sea air, wondering whether today I should order Stewed Veal "Stanley" or take a chance on the cold table's Blown Poularde "Rose of May."

MY PARENTS BELONGED TO a hierarchical and class-conscious generation. Keeping up appearances was a nerve-racking job, and nowhere was that more evident than in the British Army and the diplomatic corps.

"I feel wrong," my mother, Lyla, would often say as she stood in front of the mirror, putting on her long gloves and patting her hair in exasperation. It was a refrain I heard throughout her life. Her forehead was too high. Her curly auburn hair was too thin, her pale skin too fine and prone to wrinkles.

There was nothing wrong with her looks. My mother was a beauty. But behind the glamorous facade, she was often frightened, as if some catastrophe were about to take place and she was helpless to prevent it.

It wasn't the travel, the upheaval involved in changing countries every two years that made my mother so often feel "wrong." It was lack of money, insecurity, the rigid British class system. She was acutely aware of rank, of who was a third secretary or a counselor in the embassy, who sat "below the salt," who was placed to the left and the right of the host and hostess of a dinner party. She pronounced the word brassiere to rhyme with sassier, and flinched at the lower-middle-class words toilet, lounge (unless in a hotel or an airport) and pardon? instead of what?

She had a high upper-middle-class English voice, but her parents were Scots Irish who'd left Ulster for England in 1922 to get away from the Troubles. It was lucky that her mother had found a job as a science teacher at Sherborne School for Girls in Dorset. My grandfather, an engineer, spent much of his life either working in Africa, unemployed (during the Slump) or on sick leave, so the family scraped by.

Salaries in the diplomatic corps, moreover, were based on the assumption of a supplementary private income. Wives were not allowed to work. They were supposed to support their husbands by throwing dinners and cocktail parties, attending teas and luncheons, and knowing just enough French for the refrain, "Et combien d'enfants avez-vous, madame?"

Even food was about class distinction. The table betrayed everything. "Don't hold your knife like a pencil [lower middle class]. And don't spread your bread with butter all at once [working class]. Break off a small piece at a time [upper class]."

Working classes referred to lunch as "dinner" and dinner as "tea." Middle classes put the milk in first when they made a cup of tea. Working classes not only put the milk in first, they drank their tea at odd times of day.

Even the innocent question "What's for pudding?"--the first thing you'd ask when you sat down at the table--revealed what class you came from. The upper-class word for dessert was pudding. Lower-middle classes said sweet.

My father, Philip, didn't give a damn about any of it.

My parents were students at Cambridge when they met in 1939, the year Britain declared war on Germany. My mother read science, a subject forced upon her by my grandmother. She hated it ("I'd rather have read a book"), and went to too many parties. My father, who was on full scholarship, read modern and medieval languages. They were nothing more than friends.

After my father got his degree in 1943, he went to Sandhurst to train as an army officer. My mother tested bombs at the Royal Air Force base in Farnborough in Hampshire. She went up in a "harrier," a propeller-driven airplane with an open cockpit, and dropped dummy bombs, noting the angle of their fall.

In Farnborough, one of the officers took her out for a drink at a local pub and regaled her with tales of his dangerous flights. After lighting cigarettes for the two of them, he tossed the matchbox onto the floor.

"And there," he said, pointing down at the matchbox, "was the aircraft carrier . . ."

When she told this story, my mother would drop a matchbox on the floor and I'd gaze down at it, feeling quite vertiginous. We'd laugh, but most of those pilots hadn't come back.

My parents ran into each other again in a restaurant in London when my father was on a winter leave from Sandhurst. One evening several months later they sat in the dark in his parents' flat, which looked out over Buckingham Palace, as Hitler's bombs dropped around them. He proposed and she accepted. It all happened very fast. On July 29, 1944, when they were barely twenty-three years old, they were married in Sherborne Abbey, Lyla in a long white dress and a veil and Philip, a captain in the First Airborne Division, in a brand-new military uniform.

My mother was already pregnant with me when, just over six weeks after the wedding, on September 17, my father was dropped at Arnhem, a small town on the lower Rhine River in Holland. Operation Market Garden, as it was called, was the largest airborne campaign ever launched (the subject of the novel and film A Bridge Too Far). Its purpose was to secure the bridges that were under German occupation and advance into the Ruhr. But the British were outnumbered and suffered a crushing defeat, failing to capture the bridge at Arnhem. As they retreated from the Germans, my father gave up his place in one of the boats to a wounded friend and swam across the Rhine. Only a quarter of his unit made it back.

In May, the month I was born, my father was part of the liberation of Norway, where he received a medal from King Haakon VII. The only thing he ever told me about that time was that in Oslo he'd met a twenty-four-year-old man who had been tortured so badly by the Gestapo his hair had gone completely white. My father then spent a year in Schleswig-Holstein, where there were camps for displaced persons, involved in "mopping up" operations, whatever that meant. Like all the men in our family who came back from the war, he maintained his silence. I knew terrible things had happened that he could not bring himself to tell, and I always wondered what they were.

My father was two months younger than my mother, six foot one and very good-looking, with dark brown eyes and straight brown hair. He was born in London, the youngest child of four by a decade. My mother said this had made him taciturn. "Nobody in that family talked except his mother, who never stopped."

His father worked at the Board of Trade and was knighted by the Queen for his services. Sir Edward, a wine connoisseur who played bowls in his spare time, died at the dinner table, age seventy-five, his arm raised in a toast. But Sir Edward had had no money. So my father was always short of it too.

On his eighth birthday, while on a family holiday in Keswick, he was given a bicycle. He rode it to a sweetshop, parked by the front door, and went in to buy a chocolate bar. When he came out a few minutes later, the bicycle was gone.

"That's too bad," said his parents. "Sorry, but there we are."

They never bought him another one.

My mother thought my father was cold because, although he liked to play the clown, he rarely revealed his emotions. She came from an Irish family where books were brought down from the shelves during dinner to prove a point, exchanges were volatile and confrontational, and meals regularly wound up with the slamming of doors or fists banging down on the table, often followed by a great deal of laughter.

With Philip there was much laughter too, but few exchanges of confidences, glimmers of vulnerability or unexpected revelations about his inner life, even after a few drinks.

"He never asked what I was thinking about, either," she said. "I thought he simply didn't care"

So they had a perfectly dreadful honeymoon in Torquay, where it rained the whole time.

It was years before she realized that he was chronically shy.

Thanks to my father's job, we led a privileged life way beyond my parents' means. The government paid for private schools, servants, nannies and even chauffeurs. Cigarettes and liquor were duty-free and there was no dearth of drink: Pimm's No. 1, laced with slivers of cucumber and sprigs of mint, pink gins served straight up in martini glasses with a drop of Angostura bitters, whisky and water (no ice), a decent bottle of claret, brandy, Calvados, Madeira, Poire William, framboise, port and a digestif popular with the American wives, creme de menthe.

But wherever we were, in England or abroad, there was English food at home for the children (and often for the grown-ups too). It was familiar, stable and safe.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Delightful. . . . Hodgson’s lust for life leaps from every page.” —The Washington Times

“Engaging. . . . If [Hodgson’s] thoughtful, enjoyable recollections may be said to have a theme, it is this: ‘Food for sympathy, food for love, food for keeping death at bay.’” —The Wall Street Journal

“A veritable banquet of food and personality anecdotes.” —Liane Hansen, Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR

“[Hodgson’s] addition to the ever-growing list of food memoirs will surprise (and probably charm). . . . Delicious.” —San Francisco Weekly

“Engaging. . . . If [Hodgson’s] thoughtful, enjoyable recollections may be said to have a theme, it is this: ‘Food for sympathy, food for love, food for keeping death at bay.’” —The Wall Street Journal

“A veritable banquet of food and personality anecdotes.” —Liane Hansen, Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR

“[Hodgson’s] addition to the ever-growing list of food memoirs will surprise (and probably charm). . . . Delicious.” —San Francisco Weekly