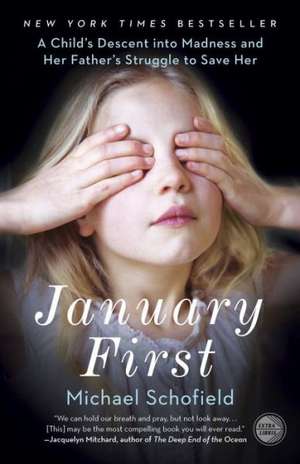

January First: A Child's Descent Into Madness and Her Father's Struggle to Save Her

Autor Michael Schofielden Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 aug 2013

Amid Jani's struggle are her parents, who face seemingly insurmountable obstacles daily just to keep both of their children alive and safe. Their battle has included a two-year search for answers, countless medications and hospitalizations, allegations of abuse, despair that almost broke the family apart and, finally, victories against the illness and a new faith that they can create a happy life for Jani.

A passionate and inspirational account, January First is a father's soul-bearing memoir of the daily challenges and unwavering commitment to save his daughter from the edge of insanity while doing everything he can to keep his family together.

Now with Extra Libris material, including a reader’s guide and bonus content

Preț: 121.71 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 183

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.30€ • 24.23$ • 19.52£

23.30€ • 24.23$ • 19.52£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 februarie-06 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307719096

ISBN-10: 030771909X

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 030771909X

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Extras

Chapter One

August 8, 2006

Today is Janni’s fourth birthday, and I’m setting up her pool party at the clubhouse in our apartment complex.

I place pool toys in the water. Janni is already splashing around.

“Come in, Daddy!”

“I’m coming, Janni. I just have to finish setting up.”

“Look, Janni!” Susan calls out. “Lynn and the twins are here. Come say hi.”

I look over to the gate where Susan is letting them in. Janni is the same age as the twins. We’ve known them since they were babies.

“Janni?” Susan calls again to her. “Come say hi to Lynn and the twins.”

“No,” Janni calls back, not even bothering to turn around and see.

“Janni, you have to welcome your guests,” Susan says, a bit more sternly.

“No!” Janni yells behind her, more forcefully this time.

“Hi, January!” Lynn calls. “Happy birthday!”

“I’m not January!” Janni screams, still not turning around. Then calmly, “I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

Lynn is visibly taken aback a little, but recovers quickly; she’s known our struggle with Janni’s constant name changing for a while now.

A year ago, Janni stopped going by her name. And this phase has gone on way longer than we thought it would. Whenever someone calls her by her real name, she screams like somebody put her hand to a hot frying pan.

We don’t even try to force her to use her given name. At this point we’re happy if she just picks one name and sticks with it. The problem is that she changes it all the time, sometimes multiple times in the same day. She’s been “Hot Dog,” “Rainbow,” “Firefly,” and now “Blue-Eyed Tree Frog,” which was originally “Red-Eyed Tree Frog,” from Go Diego! Go!, until a lady working at Sav-On drugstore pointed out, “But you have blue eyes, dear.”

“Lynn and the girls have come to your birthday party,” Susan reminds her. “You need to come and greet them.”

Janni gets out of the pool and comes over to the twins. She is not pouting. She is smiling and rubbing her hands rapidly, as if she is actually suddenly happy to see them. It’s like the previous outburst never happened.

Susan gets the twins two juice boxes from the cooler.

“Hi, Janni. How are you?” Lynn asks pleasantly.

The hand rubbing stops and the smile vanishes. “I’m not Janni! I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I forgot.” Lynn quickly corrects herself like she just received a mild electric shock.

“Girls, wish Blue-Eyed Tree Frog a happy birthday,” Lynn instructs her daughters.

“Happy birthday, Janni,” they dutifully intone. The twins have known my daughter as Janni since before they could talk. It is all they know.

“I’m not Janni!” she screams at the twins. “I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

The twins look up at their mom, confused.

“Janni!” Susan warns. “Be polite.”

I say nothing. Sure, I would like Janni to be polite, but I realize odd behavior is a by-product of her genius. She hit all of her developmental markers early and was already talking at eight months. By thirteen months she knew all her letters, both big and small, even if they were turned on their side or upside down. Then, at eighteen months, she was speaking in grammatically correct sentences, introducing herself to people saying, “I’m Janni Paige and I am eighteen months old.”

But I didn’t fully comprehend what she was capable of until I came back from grad school one evening when Janni was two and Susan was telling me about their day.

“I’ve been teaching her addition,” Susan told me, which I already knew, “so today we started on subtraction. I asked her what ‘seven minus four’ was.”

“Did she get it right?” I asked.

“Yes, she did, so we did ‘seven minus three is four.’ Then she asks me, ‘Mommy, what’s four minus seven?’ so I started trying to explain negative numbers to her.”

I stare at Susan. “She asked you what was four minus seven?”

Susan, washing dishes, turns to me. “Yeah.” She sees the look of shock on my face. “What’s wrong?”

“She asked you that right out of the blue?”

“Yes. What is it?”

Negative numbers, I remember thinking. Negative numbers are a totally abstract concept because they don’t exist in the real world. You can’t see negative four apples. At two years old, Janni’s mind made the jump from what Piaget called “concrete reasoning” to “abstract reasoning,” something that typically happens at a much older age. Janni could conceive of concepts that did not actually physically exist.

I have fantasies of Janni going to Harvard or Yale or MIT before she is even a teenager. My ultimate dream, when I close my eyes at night, is Janni winning the Nobel Prize. For what, I don’t know and don’t really care. But to be able to do what she can do at two years old, she must be a gift to humanity. I think that trumps being impolite on occasion.

“Would you like some juice?” Susan hands the twins the juice boxes and they take them.

Janni starts to laugh and flings her arm around the twins. “400 is splashing mango juice on you,” she chortles, without touching them.

The girls flinch instinctively, then look up at their mother for guidance, not sure what happened.

“400 is splashing mango juice on you.” Janni makes the move again like she is throwing juice on the twins, but she has nothing in her hand.

The twins retreat to either side of their mother.

“Janni, that isn’t nice,” Susan corrects.

“But it’s not me. It’s 400. 400 is splashing mango juice on them. She likes to splash mango juice on people.” Her arm shoots out with the imaginary juice again. We don’t even have mango juice.

The twins look up at Lynn. “You both need sunscreen.” She looks down at them, taking each daughter in one hand and over to the lounge chairs and tables.

“Well then, tell 400 to stop,” Susan tells Janni. “400 is another one of her imaginary friends,” she explains to Lynn.

Janni turns away and says to the air, “400, stop that.” She waits, apparently for a response, before turning back to the twins.

“She won’t stop.” Janni breaks into laughter again. “It is so funny. 400 is throwing mango juice on you.”

The twins are clearly scared, as Lynn puts on their sunscreen. “It’s okay, we know Janni is ‘unique.’ ”

This is frustrating. She’s being imaginative, but the twins haven’t seen imagination like this. Geniuses are often eccentric, I think to myself.

“Janni!” Susan’s voice goes up an octave. “Stop it!”

“It’s not me! It’s 400!”

“You control 400. Tell her to stop.”

Janni puts out her hands in exasperation. “I can’t!”

“Janni . . . ,” Susan begins, but I cut her off.

“Let it go.”

Janni comes over to me and and we get ready to go into the pool. This is what I do. I am her protector from the rest of the world.

I see the look of frustration on Susan’s face, but she doesn’t completely understand Janni like I do.

“She needs to greet her friends,” she tells me imploringly. “You’re not helping her learn to be polite.”

“It’s her birthday. Let it go,” I reply.

Susan opens her mouth to protest.

“Let it go,” I say again, more firmly. Susan closes her mouth and gives me an annoyed look.

I jump in the water and come up to the edge, holding out my arms. “Come on, Janni. Jump to me.”

“400 wants to jump in, too,” Janni says earnestly.

“Cats don’t generally like water.”

“Okay, you stay here, 400.”

Janni jumps to me, and I carry her out into the middle of the pool. Janni suddenly looks back at the edge.

“Oh, no! 400 fell in the pool!” she cries out. “400, don’t drown!”

“I got 400,” I answer. I put Janni down in the shallow end and wade over to where I imagine 400 to be. This is what I do that makes me different from everybody else in Janni’s life. I play along with her imaginary friends like they are real. I’ll be damned if I’m going to get lumped in with the “thirteens” in her mind. Janni says “thirteens” are kids and adults who don’t have her imagination. She considers herself a “twenty,” like me, and Susan a “seventeen,” while most of her friends are “fifteens.” But the “thirteens” have no imagination at all.

“Got her!” I fish nothing out of the water. “Ah! Now she is on my head! 400!” I pretend to sink under the weight of the imaginary cat. I will not shut any aspect of Janni down. I will not restrict anything, because I worry once she shuts down in order to conform, her full potential might be lost.

Janni smiles and laughs.

“400! Get off Daddy’s head.”

I smile back, happy.

“You know, Janni, if you could find an ocean big enough to put Saturn in it, it would float.” This is how I teach her. I engage her imaginary friends and then she pays attention.

“Do you remember what the atmospheric pressure on Venus is?”

“Ninety,” Janni answers.

“That’s right. You would weigh ninety times what you weigh on Earth. Of course, if we were on Venus right now, we’d be swimming in sulfuric acid. And then there is the heat. Venus is hotter than Mercury, even though Mercury is closer to the sun, about eight hundred degrees Fahrenheit.”

“It gets up to two hundred degrees in Calilini,” Janni says.

Here is my chance to insert a little reality into her world.

“Janni, that’s hotter than any place on Earth. That’s nearly the boiling point of water. Nothing could survive that temperature.”

“My friends do.”

“It’s not possible. Our bodies are mostly made of water, and at that temperature we would literally start to boil. How can they possibly survive?”

Janni shrugs. “They do.”

I open my mouth, ready to continue arguing the illogic of this, but Janni is drifting away from me so I let it drop.

“Janni,” I call.

She turns around.

“I still have a cat on my head.”

She smiles.

I am looking at the pizza boxes on the table.

Last year, I ordered six medium cheese pizzas and we ran out before all the guests had even arrived, so Susan wanted me to order nine this time. I did, except that now six of them sit still unopened.

Susan comes over and tells me it is time to do the cake.

“Have you told everybody to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to Blue-Eyed Tree Frog?” I ask her.

“Yes, I have,” Susan replies, knowing my fear and hers. The last thing we both want is Janni flipping out on her birthday. “Hopefully, people will remember.” She turns and calls out that it is time to light the candles.

Everybody gathers around the cake, which even says, happy birthday, blue-eyed tree frog.

“Okay, you ready?” Susan asks me.

I light the candles. Janni stands between us, rubbing her hands at a speed so fast it looks like it must be painful on her wrists, but she shows no discomfort.

“Okay . . . ,” Susan begins. “Happy birthday to you . . .”

Everybody sings along. “Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday, dear . . .”

Susan looks at me, nervously.

I sing “. . . Blue Eyed Tree Frog” at the top of my lungs, trying to lead the guests in the correct name and cut off any “mistakes” before Janni can hear them.

“Happy birthday to you!”

Everybody claps, including Janni. I look up at Susan and see her exhaling with relief, as I am.

As Susan serves the cake, I realize it is a smaller group this year. I’ve been paying attention to Janni, playing with her because she won’t play with anyone else, and didn’t notice. That explains the pizza situation. Last year people stayed for hours, long after the cake and the presents. This year, some have already left. Looking around, I realize that Lynn and the twins are gone, too.

-- Michael S. Miller Book Developer Scribe, Inc. www.scribenet.com 7540 Windsor Drive, Suite 200B Allentown PA 18195 telephone: 215.336.5094 extension 121

August 8, 2006

Today is Janni’s fourth birthday, and I’m setting up her pool party at the clubhouse in our apartment complex.

I place pool toys in the water. Janni is already splashing around.

“Come in, Daddy!”

“I’m coming, Janni. I just have to finish setting up.”

“Look, Janni!” Susan calls out. “Lynn and the twins are here. Come say hi.”

I look over to the gate where Susan is letting them in. Janni is the same age as the twins. We’ve known them since they were babies.

“Janni?” Susan calls again to her. “Come say hi to Lynn and the twins.”

“No,” Janni calls back, not even bothering to turn around and see.

“Janni, you have to welcome your guests,” Susan says, a bit more sternly.

“No!” Janni yells behind her, more forcefully this time.

“Hi, January!” Lynn calls. “Happy birthday!”

“I’m not January!” Janni screams, still not turning around. Then calmly, “I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

Lynn is visibly taken aback a little, but recovers quickly; she’s known our struggle with Janni’s constant name changing for a while now.

A year ago, Janni stopped going by her name. And this phase has gone on way longer than we thought it would. Whenever someone calls her by her real name, she screams like somebody put her hand to a hot frying pan.

We don’t even try to force her to use her given name. At this point we’re happy if she just picks one name and sticks with it. The problem is that she changes it all the time, sometimes multiple times in the same day. She’s been “Hot Dog,” “Rainbow,” “Firefly,” and now “Blue-Eyed Tree Frog,” which was originally “Red-Eyed Tree Frog,” from Go Diego! Go!, until a lady working at Sav-On drugstore pointed out, “But you have blue eyes, dear.”

“Lynn and the girls have come to your birthday party,” Susan reminds her. “You need to come and greet them.”

Janni gets out of the pool and comes over to the twins. She is not pouting. She is smiling and rubbing her hands rapidly, as if she is actually suddenly happy to see them. It’s like the previous outburst never happened.

Susan gets the twins two juice boxes from the cooler.

“Hi, Janni. How are you?” Lynn asks pleasantly.

The hand rubbing stops and the smile vanishes. “I’m not Janni! I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I forgot.” Lynn quickly corrects herself like she just received a mild electric shock.

“Girls, wish Blue-Eyed Tree Frog a happy birthday,” Lynn instructs her daughters.

“Happy birthday, Janni,” they dutifully intone. The twins have known my daughter as Janni since before they could talk. It is all they know.

“I’m not Janni!” she screams at the twins. “I’m Blue-Eyed Tree Frog.”

The twins look up at their mom, confused.

“Janni!” Susan warns. “Be polite.”

I say nothing. Sure, I would like Janni to be polite, but I realize odd behavior is a by-product of her genius. She hit all of her developmental markers early and was already talking at eight months. By thirteen months she knew all her letters, both big and small, even if they were turned on their side or upside down. Then, at eighteen months, she was speaking in grammatically correct sentences, introducing herself to people saying, “I’m Janni Paige and I am eighteen months old.”

But I didn’t fully comprehend what she was capable of until I came back from grad school one evening when Janni was two and Susan was telling me about their day.

“I’ve been teaching her addition,” Susan told me, which I already knew, “so today we started on subtraction. I asked her what ‘seven minus four’ was.”

“Did she get it right?” I asked.

“Yes, she did, so we did ‘seven minus three is four.’ Then she asks me, ‘Mommy, what’s four minus seven?’ so I started trying to explain negative numbers to her.”

I stare at Susan. “She asked you what was four minus seven?”

Susan, washing dishes, turns to me. “Yeah.” She sees the look of shock on my face. “What’s wrong?”

“She asked you that right out of the blue?”

“Yes. What is it?”

Negative numbers, I remember thinking. Negative numbers are a totally abstract concept because they don’t exist in the real world. You can’t see negative four apples. At two years old, Janni’s mind made the jump from what Piaget called “concrete reasoning” to “abstract reasoning,” something that typically happens at a much older age. Janni could conceive of concepts that did not actually physically exist.

I have fantasies of Janni going to Harvard or Yale or MIT before she is even a teenager. My ultimate dream, when I close my eyes at night, is Janni winning the Nobel Prize. For what, I don’t know and don’t really care. But to be able to do what she can do at two years old, she must be a gift to humanity. I think that trumps being impolite on occasion.

“Would you like some juice?” Susan hands the twins the juice boxes and they take them.

Janni starts to laugh and flings her arm around the twins. “400 is splashing mango juice on you,” she chortles, without touching them.

The girls flinch instinctively, then look up at their mother for guidance, not sure what happened.

“400 is splashing mango juice on you.” Janni makes the move again like she is throwing juice on the twins, but she has nothing in her hand.

The twins retreat to either side of their mother.

“Janni, that isn’t nice,” Susan corrects.

“But it’s not me. It’s 400. 400 is splashing mango juice on them. She likes to splash mango juice on people.” Her arm shoots out with the imaginary juice again. We don’t even have mango juice.

The twins look up at Lynn. “You both need sunscreen.” She looks down at them, taking each daughter in one hand and over to the lounge chairs and tables.

“Well then, tell 400 to stop,” Susan tells Janni. “400 is another one of her imaginary friends,” she explains to Lynn.

Janni turns away and says to the air, “400, stop that.” She waits, apparently for a response, before turning back to the twins.

“She won’t stop.” Janni breaks into laughter again. “It is so funny. 400 is throwing mango juice on you.”

The twins are clearly scared, as Lynn puts on their sunscreen. “It’s okay, we know Janni is ‘unique.’ ”

This is frustrating. She’s being imaginative, but the twins haven’t seen imagination like this. Geniuses are often eccentric, I think to myself.

“Janni!” Susan’s voice goes up an octave. “Stop it!”

“It’s not me! It’s 400!”

“You control 400. Tell her to stop.”

Janni puts out her hands in exasperation. “I can’t!”

“Janni . . . ,” Susan begins, but I cut her off.

“Let it go.”

Janni comes over to me and and we get ready to go into the pool. This is what I do. I am her protector from the rest of the world.

I see the look of frustration on Susan’s face, but she doesn’t completely understand Janni like I do.

“She needs to greet her friends,” she tells me imploringly. “You’re not helping her learn to be polite.”

“It’s her birthday. Let it go,” I reply.

Susan opens her mouth to protest.

“Let it go,” I say again, more firmly. Susan closes her mouth and gives me an annoyed look.

I jump in the water and come up to the edge, holding out my arms. “Come on, Janni. Jump to me.”

“400 wants to jump in, too,” Janni says earnestly.

“Cats don’t generally like water.”

“Okay, you stay here, 400.”

Janni jumps to me, and I carry her out into the middle of the pool. Janni suddenly looks back at the edge.

“Oh, no! 400 fell in the pool!” she cries out. “400, don’t drown!”

“I got 400,” I answer. I put Janni down in the shallow end and wade over to where I imagine 400 to be. This is what I do that makes me different from everybody else in Janni’s life. I play along with her imaginary friends like they are real. I’ll be damned if I’m going to get lumped in with the “thirteens” in her mind. Janni says “thirteens” are kids and adults who don’t have her imagination. She considers herself a “twenty,” like me, and Susan a “seventeen,” while most of her friends are “fifteens.” But the “thirteens” have no imagination at all.

“Got her!” I fish nothing out of the water. “Ah! Now she is on my head! 400!” I pretend to sink under the weight of the imaginary cat. I will not shut any aspect of Janni down. I will not restrict anything, because I worry once she shuts down in order to conform, her full potential might be lost.

Janni smiles and laughs.

“400! Get off Daddy’s head.”

I smile back, happy.

“You know, Janni, if you could find an ocean big enough to put Saturn in it, it would float.” This is how I teach her. I engage her imaginary friends and then she pays attention.

“Do you remember what the atmospheric pressure on Venus is?”

“Ninety,” Janni answers.

“That’s right. You would weigh ninety times what you weigh on Earth. Of course, if we were on Venus right now, we’d be swimming in sulfuric acid. And then there is the heat. Venus is hotter than Mercury, even though Mercury is closer to the sun, about eight hundred degrees Fahrenheit.”

“It gets up to two hundred degrees in Calilini,” Janni says.

Here is my chance to insert a little reality into her world.

“Janni, that’s hotter than any place on Earth. That’s nearly the boiling point of water. Nothing could survive that temperature.”

“My friends do.”

“It’s not possible. Our bodies are mostly made of water, and at that temperature we would literally start to boil. How can they possibly survive?”

Janni shrugs. “They do.”

I open my mouth, ready to continue arguing the illogic of this, but Janni is drifting away from me so I let it drop.

“Janni,” I call.

She turns around.

“I still have a cat on my head.”

She smiles.

I am looking at the pizza boxes on the table.

Last year, I ordered six medium cheese pizzas and we ran out before all the guests had even arrived, so Susan wanted me to order nine this time. I did, except that now six of them sit still unopened.

Susan comes over and tells me it is time to do the cake.

“Have you told everybody to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to Blue-Eyed Tree Frog?” I ask her.

“Yes, I have,” Susan replies, knowing my fear and hers. The last thing we both want is Janni flipping out on her birthday. “Hopefully, people will remember.” She turns and calls out that it is time to light the candles.

Everybody gathers around the cake, which even says, happy birthday, blue-eyed tree frog.

“Okay, you ready?” Susan asks me.

I light the candles. Janni stands between us, rubbing her hands at a speed so fast it looks like it must be painful on her wrists, but she shows no discomfort.

“Okay . . . ,” Susan begins. “Happy birthday to you . . .”

Everybody sings along. “Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday, dear . . .”

Susan looks at me, nervously.

I sing “. . . Blue Eyed Tree Frog” at the top of my lungs, trying to lead the guests in the correct name and cut off any “mistakes” before Janni can hear them.

“Happy birthday to you!”

Everybody claps, including Janni. I look up at Susan and see her exhaling with relief, as I am.

As Susan serves the cake, I realize it is a smaller group this year. I’ve been paying attention to Janni, playing with her because she won’t play with anyone else, and didn’t notice. That explains the pizza situation. Last year people stayed for hours, long after the cake and the presents. This year, some have already left. Looking around, I realize that Lynn and the twins are gone, too.

-- Michael S. Miller Book Developer Scribe, Inc. www.scribenet.com 7540 Windsor Drive, Suite 200B Allentown PA 18195 telephone: 215.336.5094 extension 121

Notă biografică

MICHAEL SCHOFIELD has an MA in English and teaches writing courses online for California State University at Northridge. He and his wife, Susan, are co-founders of the Jani Foundation. Michael lives with his family in Valencia, California.

Recenzii

“[Schofield’s] memoir is a wrenching, heroic narrative about a dad descending into his daughter's world to pull her back, finally, into his own.” —People

"January’s story is one of redemption, of resilience, of a family coming together in spite of all to rally for a difficult, special girl."

—New York Post

"In his memoirs January First, Michael Schofield chronicles his family's experience with [a] devastating mental illness, which usually presents itself at least a decade later."

—Daily Mail (UK)

“Imagine invisible demons that attack your beautiful child. But this is no nightmare, and no supernatural fantasy. The demons are real, and they come from inside her own mind. The story of January Schofield, diagnosed at six with childhood schizophrenia. is told by her father, Michael, with a father's tenderness, a novelist's consciousness, and a knight's grace. We can hold our breath and pray, but not look away. This modern parable may be the most compelling book you will ever read.”

—Jacquelyn Mitchard, author of The Deep End of the Ocean

“January First is a riveting and compelling-and also quite painful--story of a father’s efforts to help his young daughter find a place for herself in this world in the face of a serious mental illness. Schofield gives a glimpse inside the mind of a child who lives much of her life in another world, interacting with "friends" who are only in her mind. Schofield takes us on his journey with Jani, starting with his thoughts that Jani is simply a misunderstood genius to recognition that something is really wrong, to the ultimate diagnosis of schizophrenia, a very serious mental illness, even more so when it manifests in a child. Schofield and his wife never give up. Their dedication and steadfastness are inspirational. Their story will be highly valued by the many families with a child with mental illness-indeed, by the many families who have any kind of struggle with their kids. The book ends on a hopeful note with Jani in a better place, yet we recognize that the battle is likely not over.”

—Elyn Saks, MacArthur Grant Recipient and author of The Center Cannot Hold

"An unflinching portrait of the scourge of mental illness." —Kirkus Reviews

"In this dramatic memoir, Schofield...explains the mental illness of his young daughter...offers valuable insight for others in similar situations, and ends on a hopeful note." —Publishers Weekly

"January’s story is one of redemption, of resilience, of a family coming together in spite of all to rally for a difficult, special girl."

—New York Post

"In his memoirs January First, Michael Schofield chronicles his family's experience with [a] devastating mental illness, which usually presents itself at least a decade later."

—Daily Mail (UK)

“Imagine invisible demons that attack your beautiful child. But this is no nightmare, and no supernatural fantasy. The demons are real, and they come from inside her own mind. The story of January Schofield, diagnosed at six with childhood schizophrenia. is told by her father, Michael, with a father's tenderness, a novelist's consciousness, and a knight's grace. We can hold our breath and pray, but not look away. This modern parable may be the most compelling book you will ever read.”

—Jacquelyn Mitchard, author of The Deep End of the Ocean

“January First is a riveting and compelling-and also quite painful--story of a father’s efforts to help his young daughter find a place for herself in this world in the face of a serious mental illness. Schofield gives a glimpse inside the mind of a child who lives much of her life in another world, interacting with "friends" who are only in her mind. Schofield takes us on his journey with Jani, starting with his thoughts that Jani is simply a misunderstood genius to recognition that something is really wrong, to the ultimate diagnosis of schizophrenia, a very serious mental illness, even more so when it manifests in a child. Schofield and his wife never give up. Their dedication and steadfastness are inspirational. Their story will be highly valued by the many families with a child with mental illness-indeed, by the many families who have any kind of struggle with their kids. The book ends on a hopeful note with Jani in a better place, yet we recognize that the battle is likely not over.”

—Elyn Saks, MacArthur Grant Recipient and author of The Center Cannot Hold

"An unflinching portrait of the scourge of mental illness." —Kirkus Reviews

"In this dramatic memoir, Schofield...explains the mental illness of his young daughter...offers valuable insight for others in similar situations, and ends on a hopeful note." —Publishers Weekly