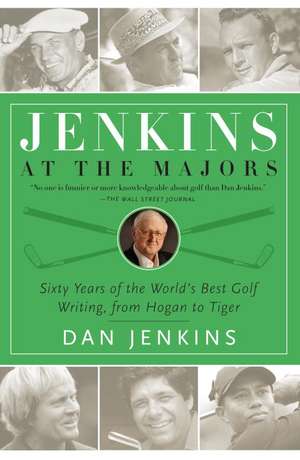

Jenkins at the Majors: Sixty Years of the World's Best Golf Writing, from Hogan to Tiger

Autor Dan Jenkinsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2010

In this seminal collection, Dan Jenkins has selected the funniest and most riveting stories from his epic career as a writer for Sports Illustrated and Golf Digest, where his wry reportage of golf’s most thrilling finishes, historic moments, and heartbreaking collapses brought legions of fans intimately close to the action. All the greatest moments of golf over the last sixty years are here: Jack Nicklaus at Pebble Beach, Arnold Palmer at Cherry Hills, Ben Hogan and Sam Snead at Oakmont, and of course Tiger Woods, just about everywhere. As much about journalism and watching the growth of one of our most cherished sports writers, as it is about the great game of golf, Jenkins at the Majors is a must read for sports fans and golfers alike.

Preț: 103.27 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.76€ • 20.42$ • 16.45£

19.76€ • 20.42$ • 16.45£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 05-19 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767925297

ISBN-10: 0767925297

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 170 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0767925297

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 170 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

DAN JENKINS, an award-winning writer for Sports Illustrated for more than twenty years, is the author of nineteen works of fiction and nonfiction, including Semi-Tough, Dead Solid Perfect, Baja Oklahoma, Life Its Ownself, Rude Behavior, Fairways and Greens, Slim and None, and most recently, The Franchise Babe. He currently writes a popular column for Golf Digest and now lives full-time in his native Fort Worth, Texas.

Extras

1

MONSTER BROUGHT TO ITS KNEES

Ben Hogan at the 1951 U.S. Open at Oakland Hills

Ben Hogan shot the greatest round of his life--maybe of anyone's life--a stunning three-under 67 in the final round of the U.S. Open championship to win it yet again, this time on the torturous layout of Oakland Hills Country Club near Detroit, but mostly what he wanted to talk about afterward was why people watch golf in the first place. Goodness, don't they have something better to do?

"The golf fan really has my respect," Ben said. "They go out there and get sunburned or rained on, they push each other around, they stand until their backs ache, and I just can't understand how they do it."

He said, "There were probably twenty thousand people out there in the last round, and fifteen thousand of them didn't see anything. There is this couple from Orange, New Jersey, that's followed me for, well, I don't know for how long. They always seem to turn up where I'm playing, and I can always spot them in the crowd."

Interesting to hear this from the man who is supposed to concentrate so deeply that walking from green to tee he's been accused on occasion of failing to recognize his wife, Valerie, when he encountered her.

Hogan went on, "There's a man from Tyler who's been watching me play for more than 10 years. And there's a fellow from Memphis--I don't even know his name--he's always in my gallery. I like to watch college football. You can see everything in reasonable comfort, and it only takes about three hours. But golf . . . I don't know."

Those who watched the golf at Oakland Hills saw the greatest player in the game win on what may have been the toughest Open course ever devised. He did it in the final hours of "Open Saturday," firing the low round of the championship and one of only two scores below 70 over the entire 72 holes. Considering that the average score of the field in the last 18 was 78 strokes, it could be argued that Hogan's closing 67--despite two bogeys--was actually 11 under.

It was Hogan's fourth Open title. That's if you count the '42 "wartime" National Open that he won at Chicago's Ridgemoor Country Club. Next was the record-setting win at Riviera in '48, then last year's comeback triumph in a playoff at Merion, and now this one.

Ben only smiled when reminded that if you ignore the '49 Open at Medinah, the championship he missed because of the near-fatal car wreck, he had actually won three in a row with the Oakland Hills victory.

Even Bobby Jones hadn't done that.

After rounds of 76 and 73, Hogan began the last 36 holes five strokes behind the halfway leader, Bobby Locke, and in a 10-way tie for 16th place.

His 71 in the morning round drew him within striking distance. At this point he was only two back of the co-leaders, Locke and Jimmy Demaret, with Julius Boros and Paul Runyan one ahead of him.

In the afternoon Ben went out directly behind Demaret at a 12-minute interval, and a full hour and a half ahead of Locke, the jowly South African whose putting style resembles a slap but who often makes life uncomfortable for American pros--by beating them on their own tour.

Overlooking the spike marks and divots, and the wear and tear on his body, the golf course Hogan conquered in that final round was a devilish thing that architect Robert Trent Jones had remodeled with orders from the club's membership to "toughen it up and make it memorable."

What Jones did was triple the number of bunkers and relocate them where they were most likely to catch drives off the tee, grow the rough up to eight or 10 inches in most spots, and pinch in the fairways to a sinister 22 yards across.

Sam Snead described the fairways after his one-over 71 led the first round. He said, "I knew it was gonna be tough when I played my first practice round. Three of us walked side by side down the first fairway, and two of us were in the rough."

One of Hogan's trademarks is that he knows how to learn from his mistakes.

At the 380-yard seventh hole in the morning round, Ben's tee shot found a brook that cut into the right side of the fairway. It cost him a bogey five. But in the afternoon he hugged the left side of the fairway from the tee, pitched to two feet of the cup, and made a birdie.

The 392-yard 15th hole featured a bunker squarely in the middle of the fairway. Hogan's drive in the morning round went too far left and became tangled in the deep rough. It cost him a double-bogey six. But in the afternoon he played a beautiful spoon off the tee and the ball sneaked safely into the narrow alley left of the bunker. Then from there, his approach was a deadly shot to within six feet of the flag, and he got another birdie.

Don't tell Ben how to get even with a golf course.

All week long, there was more grumbling and growling than usual on the part of the pros regarding the "unfairness" of Oakland Hills, but Hogan may have said it best at the presentation ceremony.

As he caressed the Open trophy, he said, "I'm glad I was finally able to bring this course, this monster, to its knees."

Actually, he called it something else in private.

From the Hardcover edition.

MONSTER BROUGHT TO ITS KNEES

Ben Hogan at the 1951 U.S. Open at Oakland Hills

Ben Hogan shot the greatest round of his life--maybe of anyone's life--a stunning three-under 67 in the final round of the U.S. Open championship to win it yet again, this time on the torturous layout of Oakland Hills Country Club near Detroit, but mostly what he wanted to talk about afterward was why people watch golf in the first place. Goodness, don't they have something better to do?

"The golf fan really has my respect," Ben said. "They go out there and get sunburned or rained on, they push each other around, they stand until their backs ache, and I just can't understand how they do it."

He said, "There were probably twenty thousand people out there in the last round, and fifteen thousand of them didn't see anything. There is this couple from Orange, New Jersey, that's followed me for, well, I don't know for how long. They always seem to turn up where I'm playing, and I can always spot them in the crowd."

Interesting to hear this from the man who is supposed to concentrate so deeply that walking from green to tee he's been accused on occasion of failing to recognize his wife, Valerie, when he encountered her.

Hogan went on, "There's a man from Tyler who's been watching me play for more than 10 years. And there's a fellow from Memphis--I don't even know his name--he's always in my gallery. I like to watch college football. You can see everything in reasonable comfort, and it only takes about three hours. But golf . . . I don't know."

Those who watched the golf at Oakland Hills saw the greatest player in the game win on what may have been the toughest Open course ever devised. He did it in the final hours of "Open Saturday," firing the low round of the championship and one of only two scores below 70 over the entire 72 holes. Considering that the average score of the field in the last 18 was 78 strokes, it could be argued that Hogan's closing 67--despite two bogeys--was actually 11 under.

It was Hogan's fourth Open title. That's if you count the '42 "wartime" National Open that he won at Chicago's Ridgemoor Country Club. Next was the record-setting win at Riviera in '48, then last year's comeback triumph in a playoff at Merion, and now this one.

Ben only smiled when reminded that if you ignore the '49 Open at Medinah, the championship he missed because of the near-fatal car wreck, he had actually won three in a row with the Oakland Hills victory.

Even Bobby Jones hadn't done that.

After rounds of 76 and 73, Hogan began the last 36 holes five strokes behind the halfway leader, Bobby Locke, and in a 10-way tie for 16th place.

His 71 in the morning round drew him within striking distance. At this point he was only two back of the co-leaders, Locke and Jimmy Demaret, with Julius Boros and Paul Runyan one ahead of him.

In the afternoon Ben went out directly behind Demaret at a 12-minute interval, and a full hour and a half ahead of Locke, the jowly South African whose putting style resembles a slap but who often makes life uncomfortable for American pros--by beating them on their own tour.

Overlooking the spike marks and divots, and the wear and tear on his body, the golf course Hogan conquered in that final round was a devilish thing that architect Robert Trent Jones had remodeled with orders from the club's membership to "toughen it up and make it memorable."

What Jones did was triple the number of bunkers and relocate them where they were most likely to catch drives off the tee, grow the rough up to eight or 10 inches in most spots, and pinch in the fairways to a sinister 22 yards across.

Sam Snead described the fairways after his one-over 71 led the first round. He said, "I knew it was gonna be tough when I played my first practice round. Three of us walked side by side down the first fairway, and two of us were in the rough."

One of Hogan's trademarks is that he knows how to learn from his mistakes.

At the 380-yard seventh hole in the morning round, Ben's tee shot found a brook that cut into the right side of the fairway. It cost him a bogey five. But in the afternoon he hugged the left side of the fairway from the tee, pitched to two feet of the cup, and made a birdie.

The 392-yard 15th hole featured a bunker squarely in the middle of the fairway. Hogan's drive in the morning round went too far left and became tangled in the deep rough. It cost him a double-bogey six. But in the afternoon he played a beautiful spoon off the tee and the ball sneaked safely into the narrow alley left of the bunker. Then from there, his approach was a deadly shot to within six feet of the flag, and he got another birdie.

Don't tell Ben how to get even with a golf course.

All week long, there was more grumbling and growling than usual on the part of the pros regarding the "unfairness" of Oakland Hills, but Hogan may have said it best at the presentation ceremony.

As he caressed the Open trophy, he said, "I'm glad I was finally able to bring this course, this monster, to its knees."

Actually, he called it something else in private.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"No one is funnier or more knowledgeable about golf than Dan Jenkins."--Wall Street Journal

"Carl Hiaasen calls Dan Jenkins 'probably the funniest sports journalist ever.' No argument here."--The New York Times

"No one has captured the essential lunacy of the twentieth-century sports scene as accurately and hilariously."--Los Angeles Times

"Hotter than a habanero pepper. . . . Jenkins brings a passion for the game and a committed intelligence to his coverage."--Richmond Times-Dispatch

"For style, outrageous humor and longevity, it's hard to top Dan Jenkins." --Newsday

“His writing and his ear recall—there is no higher compliment—Ring Lardner, though in different times and different Americas.”—David Halberstam, New York Times Book Review

"Jenkins ranks with the best and most influential sportswriters of the 20th century."--Gary VanSickle, Golf.com

"Jenkins takes us inside the world of golf like no one else."--Sacramento Bee

“Jenkins is hilarious, providing more laughs per page than any other writer in the ‘bidness.’”—People

"Carl Hiaasen calls Dan Jenkins 'probably the funniest sports journalist ever.' No argument here."--The New York Times

"No one has captured the essential lunacy of the twentieth-century sports scene as accurately and hilariously."--Los Angeles Times

"Hotter than a habanero pepper. . . . Jenkins brings a passion for the game and a committed intelligence to his coverage."--Richmond Times-Dispatch

"For style, outrageous humor and longevity, it's hard to top Dan Jenkins." --Newsday

“His writing and his ear recall—there is no higher compliment—Ring Lardner, though in different times and different Americas.”—David Halberstam, New York Times Book Review

"Jenkins ranks with the best and most influential sportswriters of the 20th century."--Gary VanSickle, Golf.com

"Jenkins takes us inside the world of golf like no one else."--Sacramento Bee

“Jenkins is hilarious, providing more laughs per page than any other writer in the ‘bidness.’”—People