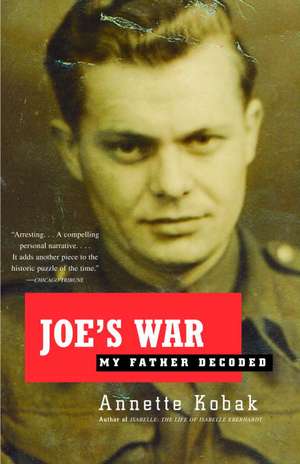

Joe's War: My Father Decoded

Autor Annette Kobaken Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2005

Born on the border of Poland and Czechoslovakia, Joe Kobak fled the Nazis, suffered imprisonment by the Russians, then joined Polish forces fighting in France. Later he escaped to London where he spent the duration of the war intercepting Soviet messages. In Joe's War, his daughter captures Joe Kobak's story in his own words, and interweaves it with her own search for a life story she can make sense of. Embarking upon a challenging and poignant journey of her own–retracing her father's footsteps across a barren and unfamiliar Ukraine–the author sheds light on the dark corners of her family history and on some of the darker aspects of the war, bringing history to life in unexpected ways.

Preț: 145.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 218

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.84€ • 28.76$ • 23.17£

27.84€ • 28.76$ • 23.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375726125

ISBN-10: 0375726128

Pagini: 444

Ilustrații: 20 PHOTOGRAPS & 2 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375726128

Pagini: 444

Ilustrații: 20 PHOTOGRAPS & 2 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Born in London, Annette Kobak studied modern languages at Cambridge University and creative writing at the University of East Anglia. She has written an acclaimed biography of the nineteenth-century traveler Isabelle Eberhardt and translated her novel Vagabond from the French. She presented the series The Art of Travel on BBC Radio 4 and reviews travel books and fiction for the New York Times Book Review and The Times Literary Supplement.

Extras

Chapter 1

THE SILENT SLAV

It didn't occur to me to ask my father as I grew up why he had nothing from his past before the war-no pictures of himself when young, no family photographs, no mementos of any kind. He was a man without a past, and I failed to notice. Since I grew up alongside the void, it seemed natural to me, as natural as the way his eyes oscillated continuously, or the way he slept with a hammer under his pillow.

Throughout my time at home in southeast London-first in a flat in Crystal Palace and then in a small, semidetached house in a drab suburb called Anerley-my father was often taciturn, irritable and cowled with gloom. His whole manner discouraged questions about himself, even if I'd been disposed to ask them, which, like most children, I wasn't. I was also my parents' only child, and, like most only children, took on the adults' coloring more than usual, being outnumbered. If the grown-ups weren't talking about something, I wasn't talking about it either.

The only facts I knew about my father as I grew up were that he'd been a soldier with the Polish army in the war and had ended up in London, where he'd met my English mother-who was in the women's air force at the time-playing table tennis. At the end of the war he'd taken a job as a watchmaker at Bravington's in Kings Cross, and at the same time studied in the evenings for a physics diploma somewhere in London. I thought he was Polish, because he'd been in the Polish army and had three Polish friends from those days. It wasn't until much later that I learned he was born in Czechoslovakia, so was technically Czechoslovak. By the time I began asking these questions, he was anyway "naturalized" British; and by the time I really started to ask him questions, he had emigrated to Australia.

After a bad war, I've read, the officers stammer and the ranks become mute. My father, who had been a foot soldier, ran true to form, his silence aggravated by being in a foreign country whose language he didn't speak at first. Although I didn't consciously know about his past, I sensed its presence by bumping up against the no-go areas protecting it. I also unwittingly adopted them as my own, and it's partly through butting up against their barbed presence in myself that I've unravelled his story, half a century later. Like the secret establishments omitted on an Ordnance Survey map, my father's past wasn't overtly acknowledged, but was very much there.

My English mother had a past and a visible one, although she was almost an orphan herself. Her mother had died when she was four, and she and her two sisters and brother were packed off to a rackety boarding school in Sussex where their first sight was of a small coffin being hustled out of the building, and where they were seldom visited by their dashing dental surgeon father, who was having problems of his own with four small children to support and a tempestuous love life. He died prematurely, too, when my mother was sixteen, and shortly after that she joined up in the WAAF and the war was on. Even though they must have been short on care-they would often be the only children left at their Dickensian school in the holidays, and it would be closed down in the end, its headmistress committed to prison-my mother and her siblings had photographs of themselves as children, buoyant and bouncy on pebbly beaches, and pictures of their ancestors. All of them grew up energetic and outgoing, sure of each other, and of where they had come from. Although my mother's father had left only debts financially, she had pieces of furniture from her past in our Crystal Palace flat: a tapestry prayer chair, a cabinet, a round mahogany table with brass clawfeet.

My father's few possessions were all to do with the war, and most were khaki, a dull color on the face of it, but as potent as Proust's madeleine to me. The first time I was asked to dance by a stranger was with a French soldier in Le Lavandou when I was fifteen, under the aegis of my French penfriend's family. It was exciting enough to be asked to dance the paso doble in a beach nightclub, the air thick with pine and the sound of crickets, let alone to feel the rough, clean khaki uniform, familiar from infancy. Later, in the sixties, I used to shop at Laurence Corner, the secondhand military store, just north of the Tottenham Court Road, favoring khaki flak jackets worn over a miniskirt. And a year or two later, against the grain of the times, I even married someone who had been a soldier. So there were the germs of an obsession there, and maybe that's what obsessions are: objects waving their hands in the air, trying to draw attention to something unresolved.

My father's tough, woolen, pocketed khaki uniform hung in my parents' wardrobe in our flat in Crystal Palace, its navy blue cap rolled under one of its epaulettes. At some point the uniform disappeared, but underneath it, stuffed in a back corner alongside a growing pile of Reader's Digests-always particularly well thumbed at "Laughter, the best medicine"-was a khaki silk parachute, its swathes of slippery material and eyelets rolled into a ball tied with white silk cords. It provided for our small household for years, a cornucopia amidst the postwar rationing, barely dwindling, it seemed, as my father clattered away on the sewing machine treadle, turning it into pocket linings, pajamas, an eiderdown cover. As a child, I slept in khaki silk pajamas he'd made, underneath a khaki eiderdown. No wonder something of his war rubbed off on my dreams.

I had a recurring nightmare of footsteps coming along the corridor to our flat, of the door opening slowly, and an ogre standing at the door. I know it's an ogre as soon as I hear the footsteps, and I run and hide behind the old mahogany radiogram, with its frayed brown weave behind a sunset fretwork. The ogre thuds over, knowing I'm there, and I wake in terror, my heart beating to the rhythm of his footsteps. Is the ogre my father? Did I, like many war babies tucked into comforting mothers' beds, resent the reappearance of my father when he came back from the war? Did he, slender and traumatized as he was, seem frightening with his uniform and his gruff, heavily-accented voice? I'm sure we babies born flanked by war breathed in extra doses of anxiety that never quite left us.

I was left to my own devices from an early age, a latchkey kid, as my parents were both out at work from when I was four-my mother working as a dental nurse an hour away to the south, my father working at Bravington's. I took myself off on the trolleybus down Anerley hill to school (longing to scroll out the buff-colored ticket from the machine like the bus conductor) and let myself back in with a doorkey on a ribbon around my neck. In the holidays, I used to roam around in the nearby Crystal Palace grounds with other children from the block of flats where we lived. Once or twice we managed to get across to the giant metal dinosaurs which prowl on the islands in the lakes. They were built by the Victorians, awestruck at having discovered that such creatures once existed, and conjuring up what they thought they must have looked like. We climbed up into the dinosaurs' echoing insides through holes in their bellies, and roared out from their mouths at passing lovers. In a photograph my father took of me in the Crystal Palace grounds with the dinosaurs, I'm not the freewheeling urchin I remember, but stand solemnly, with a proper coat and dress, looking sad. It's taken me all this time to turn around and notice those dinosaurs roaring silently behind me, and figure out what they were.

My father's three Polish friends from the army sometimes came to the flat for lunch on a Sunday: W¢adek, Stanley, and Ted-W¢adyslaw, Stanis¢aw and Tadeusz, as they'd been in Polish. My father became animated and boyish when he was with them, quite different from the moody, grumpy person he was for much of the rest of the time.

Ted would bring whiskey from the pub in Herne Hill where he worked. He was small, cheery and stocky, the type of Polish immigrant who fuelled Hollywood after the war, like Gene Kelly, who-you only notice later when you're grown up-is very short from shoulder to waist. My father always seemed to defer to Ted. Stan was gangly, chain-smoking and intellectual, his dry reddish hair ruffled and unkempt, kept that way by raking it periodically with long nicotine-stained fingers. He was a bachelor, with a nervous edge I found appealing. He never had any money, and would come from Balham by bus, glad of the home cooking as much as the camaraderie. I only saw W¢adek a few times, as he went off to Argentina when I was small and we never heard from him again, except for one letter to me in which he said he hadn't been eaten by crocodiles. I marvelled that he could guess that it was exactly what I was worried about. Before he left, he gave me a Teddy bear, its body long like a newborn baby's, its brown face solemn, the hump on its back and its low growl when you bent it over suggestive of grown-up cares.

My father seemed the youngest of them all. I could see he was proud to play host to them, bending down with exaggerated courtesy at their elbows, looking intensely into their faces to ask them what they'd like to drink, wringing his hands in anticipation. His light brown backwash of wavy hair, usually brushed away from his forehead, would spring forward. After lunch, the men would unfold a card table and settle down to playing cards, setting their amber drinks reverentially beside them, along with a brass ashtray made from an old bombshell. My father was the only one who never smoked. They would speak in Polish, a passport into a more raffish, virile land. The air grew thick with smoke and the mellifluous, clashing consonants of a language neither my mother nor I could speak. I wanted my father to teach me, but he laughed it off, saying with mock gruffness: "Oh you want to learn Polish, do you, well, what on earth do you want to learn that for?" Although it wasn't funny, he would say it as if it was, and more to impress Stan and Ted and W¢adek than to answer my question. I would draw them all in a sketchbook, for want of anything better to do, and for want of other children around. They were completely unself-conscious, and I became an observer. Outside the flat, the air of an English winter afternoon that had never quite roused itself into daylight would congeal particle by particle into twilight. Inside, the air would thicken with smoke, the peeling mica in the grille of the coal-burning stove would crackle with heat, arms would describe more fulsome arcs, or thump down triumphantly on the table as somebody won a game. When my father won, he might brag abandonedly, beating his breast with pleasure, or he might shrug it off gently as if it wasn't him but some outside force that had done it. Once W¢adek had gone away, my mother would join in the foursome, playing as volubly as they did. She smoked from a cigarette holder, which seemed to give her more control than she usually had.

In due course my father taught me a few numbers in Polish-jeden, dwa, trzy, cztery-as well as poker and canasta. I was the only child any of them had for a long time, and became good at cards, although I never did manage to cut and deal the cards as whistle-fast as they did, or fan out thirteen cards in one hand, or flip a whole pack through the air from hand to hand like an accordion. Card playing seemed to be the natural activity of grown-ups whenever they got together.

On our own on a Sunday, we would listen to Forces' Favourites, which later became Two-Way Family Favourites. Jean Metcalfe, Cliff Michelmore and André Kostelanetz's "With a Song in My Heart" were as much part of our furniture as the mahogany radiogram in the corner. "Lance-bombardier Frank Medway stationed in München-Gladbach would like us to play Pat Boone's 'I'll Be Home' for his sweetheart Valerie in Luton. It won't be long now, he says." "The forces," along with card playing, seemed to be where the adult action was. The forces were definitely with us. To have been in the forces seemed to give people weight and anchorage. My mother's relatives had all been in the forces in the war, as she had been. I knew my father had been a soldier, too, but that somehow didn't rate as being in the forces, which seemed to be an exclusively English thing. My mother's brother was so much in the forces that he stayed there, commanding his own RAF station, an aura of glamour around him as a result. He was clearly part of what won the war. However, neither he nor any of the other relatives, nor anyone else we knew, ever asked my father about his war, and I sensed that my father's part in it, whatever it was, was best left unsaid. He wasn't an officer, for a start, and then he was foreign, so his part in it was liable to be murky. For of course we knew-we kids who played "Japs and Germans" in the back garden of the block of flats-that it was foreigners we fought in the war, and it was we, the British, who won the war against them. It was Churchill and Douglas Bader and the Dam Busters who won the war: all British. Part of the reason I didn't even think of asking my father about his previous, foreign life is that I didn't know the right questions or even geography, and part was that I felt uneasy about what I might find. His past was literally a foreign country. If I did now and then venture a question, he would comically exaggerate his usual brow-furrowing, then growl and pounce at me, shooing me away from the thing he didn't want to talk about, or running at me in a slightly manic way, the way he ran at a cat if he saw one in the garden.

From the Hardcover edition.

THE SILENT SLAV

It didn't occur to me to ask my father as I grew up why he had nothing from his past before the war-no pictures of himself when young, no family photographs, no mementos of any kind. He was a man without a past, and I failed to notice. Since I grew up alongside the void, it seemed natural to me, as natural as the way his eyes oscillated continuously, or the way he slept with a hammer under his pillow.

Throughout my time at home in southeast London-first in a flat in Crystal Palace and then in a small, semidetached house in a drab suburb called Anerley-my father was often taciturn, irritable and cowled with gloom. His whole manner discouraged questions about himself, even if I'd been disposed to ask them, which, like most children, I wasn't. I was also my parents' only child, and, like most only children, took on the adults' coloring more than usual, being outnumbered. If the grown-ups weren't talking about something, I wasn't talking about it either.

The only facts I knew about my father as I grew up were that he'd been a soldier with the Polish army in the war and had ended up in London, where he'd met my English mother-who was in the women's air force at the time-playing table tennis. At the end of the war he'd taken a job as a watchmaker at Bravington's in Kings Cross, and at the same time studied in the evenings for a physics diploma somewhere in London. I thought he was Polish, because he'd been in the Polish army and had three Polish friends from those days. It wasn't until much later that I learned he was born in Czechoslovakia, so was technically Czechoslovak. By the time I began asking these questions, he was anyway "naturalized" British; and by the time I really started to ask him questions, he had emigrated to Australia.

After a bad war, I've read, the officers stammer and the ranks become mute. My father, who had been a foot soldier, ran true to form, his silence aggravated by being in a foreign country whose language he didn't speak at first. Although I didn't consciously know about his past, I sensed its presence by bumping up against the no-go areas protecting it. I also unwittingly adopted them as my own, and it's partly through butting up against their barbed presence in myself that I've unravelled his story, half a century later. Like the secret establishments omitted on an Ordnance Survey map, my father's past wasn't overtly acknowledged, but was very much there.

My English mother had a past and a visible one, although she was almost an orphan herself. Her mother had died when she was four, and she and her two sisters and brother were packed off to a rackety boarding school in Sussex where their first sight was of a small coffin being hustled out of the building, and where they were seldom visited by their dashing dental surgeon father, who was having problems of his own with four small children to support and a tempestuous love life. He died prematurely, too, when my mother was sixteen, and shortly after that she joined up in the WAAF and the war was on. Even though they must have been short on care-they would often be the only children left at their Dickensian school in the holidays, and it would be closed down in the end, its headmistress committed to prison-my mother and her siblings had photographs of themselves as children, buoyant and bouncy on pebbly beaches, and pictures of their ancestors. All of them grew up energetic and outgoing, sure of each other, and of where they had come from. Although my mother's father had left only debts financially, she had pieces of furniture from her past in our Crystal Palace flat: a tapestry prayer chair, a cabinet, a round mahogany table with brass clawfeet.

My father's few possessions were all to do with the war, and most were khaki, a dull color on the face of it, but as potent as Proust's madeleine to me. The first time I was asked to dance by a stranger was with a French soldier in Le Lavandou when I was fifteen, under the aegis of my French penfriend's family. It was exciting enough to be asked to dance the paso doble in a beach nightclub, the air thick with pine and the sound of crickets, let alone to feel the rough, clean khaki uniform, familiar from infancy. Later, in the sixties, I used to shop at Laurence Corner, the secondhand military store, just north of the Tottenham Court Road, favoring khaki flak jackets worn over a miniskirt. And a year or two later, against the grain of the times, I even married someone who had been a soldier. So there were the germs of an obsession there, and maybe that's what obsessions are: objects waving their hands in the air, trying to draw attention to something unresolved.

My father's tough, woolen, pocketed khaki uniform hung in my parents' wardrobe in our flat in Crystal Palace, its navy blue cap rolled under one of its epaulettes. At some point the uniform disappeared, but underneath it, stuffed in a back corner alongside a growing pile of Reader's Digests-always particularly well thumbed at "Laughter, the best medicine"-was a khaki silk parachute, its swathes of slippery material and eyelets rolled into a ball tied with white silk cords. It provided for our small household for years, a cornucopia amidst the postwar rationing, barely dwindling, it seemed, as my father clattered away on the sewing machine treadle, turning it into pocket linings, pajamas, an eiderdown cover. As a child, I slept in khaki silk pajamas he'd made, underneath a khaki eiderdown. No wonder something of his war rubbed off on my dreams.

I had a recurring nightmare of footsteps coming along the corridor to our flat, of the door opening slowly, and an ogre standing at the door. I know it's an ogre as soon as I hear the footsteps, and I run and hide behind the old mahogany radiogram, with its frayed brown weave behind a sunset fretwork. The ogre thuds over, knowing I'm there, and I wake in terror, my heart beating to the rhythm of his footsteps. Is the ogre my father? Did I, like many war babies tucked into comforting mothers' beds, resent the reappearance of my father when he came back from the war? Did he, slender and traumatized as he was, seem frightening with his uniform and his gruff, heavily-accented voice? I'm sure we babies born flanked by war breathed in extra doses of anxiety that never quite left us.

I was left to my own devices from an early age, a latchkey kid, as my parents were both out at work from when I was four-my mother working as a dental nurse an hour away to the south, my father working at Bravington's. I took myself off on the trolleybus down Anerley hill to school (longing to scroll out the buff-colored ticket from the machine like the bus conductor) and let myself back in with a doorkey on a ribbon around my neck. In the holidays, I used to roam around in the nearby Crystal Palace grounds with other children from the block of flats where we lived. Once or twice we managed to get across to the giant metal dinosaurs which prowl on the islands in the lakes. They were built by the Victorians, awestruck at having discovered that such creatures once existed, and conjuring up what they thought they must have looked like. We climbed up into the dinosaurs' echoing insides through holes in their bellies, and roared out from their mouths at passing lovers. In a photograph my father took of me in the Crystal Palace grounds with the dinosaurs, I'm not the freewheeling urchin I remember, but stand solemnly, with a proper coat and dress, looking sad. It's taken me all this time to turn around and notice those dinosaurs roaring silently behind me, and figure out what they were.

My father's three Polish friends from the army sometimes came to the flat for lunch on a Sunday: W¢adek, Stanley, and Ted-W¢adyslaw, Stanis¢aw and Tadeusz, as they'd been in Polish. My father became animated and boyish when he was with them, quite different from the moody, grumpy person he was for much of the rest of the time.

Ted would bring whiskey from the pub in Herne Hill where he worked. He was small, cheery and stocky, the type of Polish immigrant who fuelled Hollywood after the war, like Gene Kelly, who-you only notice later when you're grown up-is very short from shoulder to waist. My father always seemed to defer to Ted. Stan was gangly, chain-smoking and intellectual, his dry reddish hair ruffled and unkempt, kept that way by raking it periodically with long nicotine-stained fingers. He was a bachelor, with a nervous edge I found appealing. He never had any money, and would come from Balham by bus, glad of the home cooking as much as the camaraderie. I only saw W¢adek a few times, as he went off to Argentina when I was small and we never heard from him again, except for one letter to me in which he said he hadn't been eaten by crocodiles. I marvelled that he could guess that it was exactly what I was worried about. Before he left, he gave me a Teddy bear, its body long like a newborn baby's, its brown face solemn, the hump on its back and its low growl when you bent it over suggestive of grown-up cares.

My father seemed the youngest of them all. I could see he was proud to play host to them, bending down with exaggerated courtesy at their elbows, looking intensely into their faces to ask them what they'd like to drink, wringing his hands in anticipation. His light brown backwash of wavy hair, usually brushed away from his forehead, would spring forward. After lunch, the men would unfold a card table and settle down to playing cards, setting their amber drinks reverentially beside them, along with a brass ashtray made from an old bombshell. My father was the only one who never smoked. They would speak in Polish, a passport into a more raffish, virile land. The air grew thick with smoke and the mellifluous, clashing consonants of a language neither my mother nor I could speak. I wanted my father to teach me, but he laughed it off, saying with mock gruffness: "Oh you want to learn Polish, do you, well, what on earth do you want to learn that for?" Although it wasn't funny, he would say it as if it was, and more to impress Stan and Ted and W¢adek than to answer my question. I would draw them all in a sketchbook, for want of anything better to do, and for want of other children around. They were completely unself-conscious, and I became an observer. Outside the flat, the air of an English winter afternoon that had never quite roused itself into daylight would congeal particle by particle into twilight. Inside, the air would thicken with smoke, the peeling mica in the grille of the coal-burning stove would crackle with heat, arms would describe more fulsome arcs, or thump down triumphantly on the table as somebody won a game. When my father won, he might brag abandonedly, beating his breast with pleasure, or he might shrug it off gently as if it wasn't him but some outside force that had done it. Once W¢adek had gone away, my mother would join in the foursome, playing as volubly as they did. She smoked from a cigarette holder, which seemed to give her more control than she usually had.

In due course my father taught me a few numbers in Polish-jeden, dwa, trzy, cztery-as well as poker and canasta. I was the only child any of them had for a long time, and became good at cards, although I never did manage to cut and deal the cards as whistle-fast as they did, or fan out thirteen cards in one hand, or flip a whole pack through the air from hand to hand like an accordion. Card playing seemed to be the natural activity of grown-ups whenever they got together.

On our own on a Sunday, we would listen to Forces' Favourites, which later became Two-Way Family Favourites. Jean Metcalfe, Cliff Michelmore and André Kostelanetz's "With a Song in My Heart" were as much part of our furniture as the mahogany radiogram in the corner. "Lance-bombardier Frank Medway stationed in München-Gladbach would like us to play Pat Boone's 'I'll Be Home' for his sweetheart Valerie in Luton. It won't be long now, he says." "The forces," along with card playing, seemed to be where the adult action was. The forces were definitely with us. To have been in the forces seemed to give people weight and anchorage. My mother's relatives had all been in the forces in the war, as she had been. I knew my father had been a soldier, too, but that somehow didn't rate as being in the forces, which seemed to be an exclusively English thing. My mother's brother was so much in the forces that he stayed there, commanding his own RAF station, an aura of glamour around him as a result. He was clearly part of what won the war. However, neither he nor any of the other relatives, nor anyone else we knew, ever asked my father about his war, and I sensed that my father's part in it, whatever it was, was best left unsaid. He wasn't an officer, for a start, and then he was foreign, so his part in it was liable to be murky. For of course we knew-we kids who played "Japs and Germans" in the back garden of the block of flats-that it was foreigners we fought in the war, and it was we, the British, who won the war against them. It was Churchill and Douglas Bader and the Dam Busters who won the war: all British. Part of the reason I didn't even think of asking my father about his previous, foreign life is that I didn't know the right questions or even geography, and part was that I felt uneasy about what I might find. His past was literally a foreign country. If I did now and then venture a question, he would comically exaggerate his usual brow-furrowing, then growl and pounce at me, shooing me away from the thing he didn't want to talk about, or running at me in a slightly manic way, the way he ran at a cat if he saw one in the garden.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Arresting . . . A compelling personal narrative. . . . It adds another piece to the historic puzzle of the time." –Chicago Tribune

“Admirable. . . . Part memoir, part biography, part travelogue and (in its most stirring and valuable sections) part history of the great sorrows and tragedies endured by the Czechs and Poles all through the twentieth century. . . . Reading this moving, one-of-a-kind work, a reader wants to cheer, in at least three languages.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“Totally engrossing and written with such grace [that] it flows from page to page effortlessly.” –Tucson Citizen

“Kobak is a smart, even elegant writer, capable of pithy observations that jump off the page.” –The Washington Post

“[Kobak] points out that Australia’s Aborigines believe that ‘our stories are what we are here for.’ By finally learning her father’s story, she recognizes, her own becomes much richer.” –Newsweek

“Kobak’s thrilling race to discovery carries the reader along. Like her, we can’t wait to know what happened next, and why; like her we are filled with hopeless fury as politicians abolish lives and nations to ingratiate themselves with other politicians. We applaud breathlessly as Joe slips one trap after another, and stand fascinated as chance meetings lead to serendipitous revelations . . . Annette Kobak both reveals a Europe we never knew, and points up the importance of knowing it.” –The Independent

“This moving book finally tells the story that Kobak never heard in her childhood. It is the story of one Central European man’s war, and a success story about tact, love and trust slowly putting right the damage done by past trauma. But it is also, because of the nature of his experiences and the subtlety and intelligence with which she approaches them, the story of the twentieth century.” –Times Literary Supplement (London)

“A fascinating and enjoyable book. Eminently readable, it rambles engagingly and instructively through many spheres, private and public, leaving one with haunting reflections.” –Sunday Times (London)

“As well as being a meditation on the way that stories which once seemed frozen behind the iron curtain are now thawing back to life, Joe’s War is also a frank account of the impossibility of ever fully realising that your parents once knew a time that did not include you.” –The Guardian

“Joe Kobak’s tale of escape, engagingly told in his own words by his daughter, would stand alone very well as a war memoir. It is gripping and studded with humour. . . Its description of the chaos is reminiscent of the Dunkirk scenes in Ian McEwan’s Atonement. But this war memoir is only one strand of . . . this complex and unusual book.” –The Sunday Telegraph

“Admirable. . . . Part memoir, part biography, part travelogue and (in its most stirring and valuable sections) part history of the great sorrows and tragedies endured by the Czechs and Poles all through the twentieth century. . . . Reading this moving, one-of-a-kind work, a reader wants to cheer, in at least three languages.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“Totally engrossing and written with such grace [that] it flows from page to page effortlessly.” –Tucson Citizen

“Kobak is a smart, even elegant writer, capable of pithy observations that jump off the page.” –The Washington Post

“[Kobak] points out that Australia’s Aborigines believe that ‘our stories are what we are here for.’ By finally learning her father’s story, she recognizes, her own becomes much richer.” –Newsweek

“Kobak’s thrilling race to discovery carries the reader along. Like her, we can’t wait to know what happened next, and why; like her we are filled with hopeless fury as politicians abolish lives and nations to ingratiate themselves with other politicians. We applaud breathlessly as Joe slips one trap after another, and stand fascinated as chance meetings lead to serendipitous revelations . . . Annette Kobak both reveals a Europe we never knew, and points up the importance of knowing it.” –The Independent

“This moving book finally tells the story that Kobak never heard in her childhood. It is the story of one Central European man’s war, and a success story about tact, love and trust slowly putting right the damage done by past trauma. But it is also, because of the nature of his experiences and the subtlety and intelligence with which she approaches them, the story of the twentieth century.” –Times Literary Supplement (London)

“A fascinating and enjoyable book. Eminently readable, it rambles engagingly and instructively through many spheres, private and public, leaving one with haunting reflections.” –Sunday Times (London)

“As well as being a meditation on the way that stories which once seemed frozen behind the iron curtain are now thawing back to life, Joe’s War is also a frank account of the impossibility of ever fully realising that your parents once knew a time that did not include you.” –The Guardian

“Joe Kobak’s tale of escape, engagingly told in his own words by his daughter, would stand alone very well as a war memoir. It is gripping and studded with humour. . . Its description of the chaos is reminiscent of the Dunkirk scenes in Ian McEwan’s Atonement. But this war memoir is only one strand of . . . this complex and unusual book.” –The Sunday Telegraph