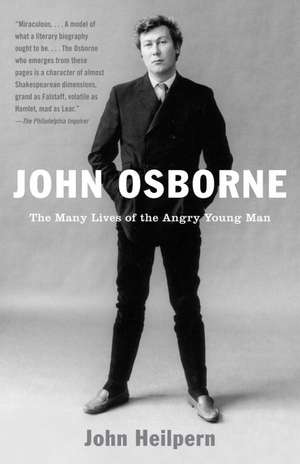

John Osborne: The Many Lives of the Angry Young Man

Autor John Heilpernen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2007

Through a working-class childhood and five marriages, Osborne led a tumultuous life. An impossible father, he threw his teenage daughter out of the house and never spoke to her again. His last written words were "I have sinned." Theater critic John Heilpern’s detailed portrait, including interviews with Osborne's daughter, scores of friends and enemies, and his alleged male lover, shows us a contradictory genius–an ogre with charm, a radical who hated change, and above all, a defiant individualist.

Preț: 103.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.73€ • 20.38$ • 16.42£

19.73€ • 20.38$ • 16.42£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375702952

ISBN-10: 0375702954

Pagini: 527

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375702954

Pagini: 527

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

John Heilpern is the author of the classic book about theater Conference of the Birds: The Story of Peter Brook in Africa and of How Good is David Mamet, Anyway?, a collection of his theater essays and reviews. Born in England and educated at Oxford, his interviews for The Observer (London) received a British Press Award. In 1980 he moved to New York, where he became a weekly columnist for The Times of London. An adjunct professor of drama at Columbia University, he is drama critic for the New York Observer.

Extras

1

The Hurst

I may be a poor playwright, but I have the best view in England—

John Osborne at home in Shropshire

As I remember it now, when I first visited Osborne’s house in Clun, deep in the Shropshire hills, I was struck by its remoteness from what he called the kulcher of London. Though a dramatist may write as well in the tweedy shires as in literary Hampstead, it was as if he had fled all contact with the theatre that had been his life. He moved to Shropshire for good with his wife, Helen, in 1986 and the Clun valley with its surly sheep, close to the Welsh border in Housman country, is about as far from the metropolis as you can get without actually leaving England.

Clunton and Clunbury; Clungunford and Clun

Are the quietest places under the sun

—A. E. Housman, not at his best.

The famously urban dramatist was a countryman at heart who loved the place as his own chunk of ancient England, unless, that is, he was the play-acting poseur some took him for. He began as an actor, after all. What role, then, was he playing? Former Angry Young Man now morphed into curmudgeonly country squire? The noncomformist clamped as brawling Tory blimp? The ex-playwright? He had taken to signing his name “John Osborne, ex-playwright” even as he continued struggling with new plays in the wreckage of a life ruled by disorder and passion. Had he become that sentimental relic or absurdist thing, an English Gentleman? But Osborne, everyone knew, wasn’t a gentleman.

He was almost a gentleman. Scholarly literary critics attributed the title of his second volume of autobiography in 1991, Almost a Gentleman, to Cardinal Newman. Osborne had quoted from Newman’s The Idea of a University, 1852, in a learned epigraph: “It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain.” The problem with scholarly critics, however, is they don’t know their Music Hall. He didn’t owe the title to the exalted source of Newman, but more typically to the low comedy of one of Music Hall’s great solo warriors in comic danger known as Billy “Almost a Gentleman” Bennett.

A rousing poetic monologuist—“Well, it rhymes!”—Bennett reached the height of his considerable fame in the 1920s and ’30s. He was billed as “Almost a Gentleman.” His signature tune, “She Was Poor, But She Was Honest,” was renowned:

It’s the same the whole world over,

It’s the poor what gets the blame.

It’s the rich what gets the pleasure,

Isn’t it a blooming shame?

Osborne was no intellectual and Billy Bennett’s sunny vulgarity and pathos appealed to his taste. Bennett also created surreal acts entitled “Almost a Ballet Dancer” and “Almost Napoleon.” But it was “Almost a Gentleman” that made his name as he nobly played his part in ill-fitting evening dress and army boots. Thus Osborne posed stagily for a Lord Snowdon portrait for the cover of his autobiography in full country gentleman regalia—tweed jacket, buttoned waistcoat, fob watch, umbrella—all topped off nicely with the prop of a flat cap, traditional emblem of the working man. But if we look closer at the Snowdon picture, this image of the sixty-year- old dramatist is too raffish to be gentlemanly. The tweed cap is at a jaunty angle, there’s a dandy in the foppish, velvet bow tie, a showman in the long silk scarf draped over-casually round his shoulders. The opal signet ring he’s wearing suggests an actor- manager of the old school or perhaps a refined antiques dealer of a certain age. The distinguished film and theatre director Lindsay Anderson, known to Osborne as “The Singing Nun,” wondered if he was auditioning in the photograph for the role of Archie Rice’s old Edwardian dad. But his chin is up, as Anderson shrewdly noted, his expression still defiant, promising combat outside the Queensberry rules.

I was visiting the Osborne home, The Hurst, three years after he died on Christmas Eve, 1994, and as the car nosed up the long driveway that winds through neighbouring farmland I was unprepared for the grandeur of the 1812 manor house on the hill. The Hurst with its twenty rooms is set in handsome, stony isolation on thirty acres with well-trodden garden paths through woodland and orchard, a clock tower, various outbuildings, and a village-size pond big enough for its own island and plentiful trout.

I had anticipated something much less impressive even by Osborne’s standards—a cottage perhaps, or country pile overgrown with weeds. I’d heard that he had been in financial trouble for years, and was all but bankrupt when he died. In fact, local tradesmen had cut off his credit at one low point and he was left sleepless with anxiety that the house itself would be foreclosed on by the bank.

Two years before his death, three of his friends had grown so alarmed at the state of his finances, they organised a meeting to try to help him. There were various plans to sell the copyrights of his plays in return for a lump sum to settle debts. But one of the problems they hoped to solve was the fact that Osborne spent more than he earned. Playwright David Hare, theatre producer Robert Fox, and Robert McCrum, Osborne’s editor at Faber & Faber, met him at the Cadogan Hotel in Belgravia where he stayed when visiting London. He nicknamed it “Oscar’s Place” (Oscar Wilde was arrested there). But he was a proud man and the meeting with the three do-gooders went disastrously.

“You might try cutting back a bit on the champagne, John,” one of them had the temerity to suggest.

It was like asking someone to breathe less oxygen. Osborne and champagne were as inseparable as Fortnum & Mason. He drank it from a silver tankard—“like white wine,” as his third wife, Penelope Gilliatt, observed dryly. When in younger days he shared a flat with the director Tony Richardson, the only food they ever had in the place was a fridge full of Dom Perignon and oranges. When he was married to wife number four, Jill Bennett, they kept a fridge in the bedroom to save them the inconvenience of going downstairs to fetch the “shampoo.”

On summer days at The Hurst, he greeted guests dressed in a boater and striped blazer like a rep actor in a touring production of The Boy Friend as he held up a bottle of champagne in welcome.

“And I can tell you this,” he protested at the meeting, flooring them all. “I’m not getting rid of the horses!”

His two trusty hacks, as indestructible as tractors rusting in a barn, had been in the family for years, along with two donkeys and three dogs. But broke he was. “Hang onto the house, if you possibly can,” he said to his wife during the last days.

“Welcome to Chateau Calamity,” she said with a smile when I arrived, and offered me champagne.

It had come as a surprise when Helen Osborne telephoned me unexpectedly in New York, where I’ve lived for many years, and said with typical diffidence, “I don’t suppose you would be interested in writing John’s authorized biography?”

My first instinct was to run. “It’s certainly an honour to be asked,” I said, playing for time.

“Well, you don’t sound very honoured,” she replied, which was also typical.

I first knew her when she was Helen Dawson, the admired arts editor and sometime drama critic of the Observer in the heyday of David Astor’s editorship during the 1960s. I joined the paper soon after her, and often sought out her company as she beavered away behind filing cabinets. Osborne famously dismissed critics as treacherous parasites, but he married two of them—Helen Dawson and film critic Penelope Gilliatt. Then again, he said of actresses that they made impossible mistresses and even worse wives, and he married three—his first wife, actress Pamela Lane; second wife, Mary Ure; and fourth wife, Jill Bennett.

His fifth—or “Numero Cinque” as Osborne often called her—was the only one of his wives, it’s widely believed, to make him happy. They were married on 2 June 1978, and lived together for eighteen years. They were apart for no more than a few days during all that time.

It was through my friendship with Helen at the Observer that I eventually got to know Osborne a little, though I had met him earlier when his 1968 play The Hotel in Amsterdam with Paul Scofield was playing in Brighton—Osborne’s favourite place on earth, lost paradise of the dirty weekend. “Oh blimey—not you again!” the stage carpenter would greet him, whenever one of his plays opened at Brighton’s Theatre Royal. He looked elegant and young when we met that day. He said hello in a slightly camp, relaxed drawl, and he clearly didn’t give a damn. I remember envying him a bit. He was on top of the world, or so it seemed.

Soon afterwards, I met him again and he looked at me suspiciously. I was wearing Paul Scofield’s suit from the play.

My first wife designed the costumes for two of Osborne’s plays, and The Hotel in Amsterdam was one of them. Scofield’s suit had been specially made for the production by Doug Hayward, the bespoke Savile Row tailor to the stars. Hayward was tailor to the dandyish John Osborne. The suit itself was an amazing hunter green with black brocade round the lapels. (This was the Sixties.) But Scofield didn’t actually wear it in the play because it didn’t suit him. It was therefore up for grabs.

Although it was a little tight on me, I was proudly wearing it, after a decent interval, when I bumped into Osborne at Don Luigi’s restaurant in the King’s Road.

“And how are yew?” he asked, still looking doubtfully at me in the treasured suit.

I subsequently met him socially on several occasions and each time he struck me as the very opposite of his combative image. I found him a gentle man, and almost excessively polite. He was gossipy and fun, and highly instinctive. And there were times when he seemed surprisingly vulnerable—as if camouflaging some sadness.

I saw him again when he and Helen were in New York during the Eighties. The city still enchanted him. He had first visited Manhattan in his meteoric twenties when two of his plays were running simultaneously on Broadway (Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer). One night, we were walking along Broadway back to the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street, where he always stayed, when he began to lean forward peculiarly like a strange version of Groucho Marx in a strong headwind. He told me it was the best way to walk, particularly over long distances, and called it “The Countryman Tramp’s Walk.” It had been taught to him by his eccentric grandfather. And now he taught it to me. We tried it out together, doing the Countryman Tramp’s Walk along the Great White Way, and even New Yorkers, who’ve seen everything, looked curious as we surged past them.

The last time I saw him was when he visited New York again with Helen in September 1984. He was then fifty-four and his plays were out of fashion. But they were a relaxed couple, enjoying each other’s company —enjoying treats. He greeted me with an affectionate, whiskery kiss smack on the lips, which pleased us both, like sharing a secret.

That night, the three of us went to the Algonquin’s Oak Room for a jolly supper and cabaret, and drank so much champagne I had to go to bed for two days afterwards. When the cabaret finished, the pianist went to shake the hands of the audience, as entertainers in New York like to do, and Osborne looked suddenly embarrassed. “He won’t remember me,” he murmured disconsolately.

“Welcome back, Mr. Osborne,” the pianist greeted him, shaking his hand warmly.

“Well, thank you very much!” he replied, beaming.

The evening went swimmingly after that. We talked about the great Music Hall artists who had influenced him. He saw them as a warrior class of gods and heroes even in pitiful failure like Archie Rice in The Entertainer. When I told him that I’d seen the wrecked comic genius Max Wall perform the same hilarious act six times, he was mightily impressed. He had cast the legendary, old comic as Archie in his own production of The Entertainer during the Seventies. To his delight, he remembered that Max asked him during rehearsals if he could add just one line to the famous play. The intrigued, but wary, Osborne replied, “Of course, Max. But what’s the line?”

It was, “Take my wife, puh-leeze!”

Osborne could scarcely stop laughing. (And the line went in the play.)

Now, over a decade later, I was visiting his widow for the first of several visits to begin work on his biography.

Two slobbering chocolate labradors flattened me against the front door of The Hurst in muddy confusion. “Down boys!” Helen Osborne ordered. But the boys, when up, seemed practically her size. At only five-foot-two, she was petite. (Her husband was tall and rangy, over six feet.)

Once inside this well-lit place, however, it was clear that, countryman or no, only a man of the theatre had once lived there. The hallway was crowded with framed posters of several of the plays. Leonard Rosoman paintings of the 1965 production of A Patriot for Me ascended the staircase. Surprisingly corny cushions spelt out embroidered messages from a bench: “You ARE leaving on Sunday, aren’t you?” “It is difficult to soar like an eagle when you’re surrounded by turkeys.” “Eat Drink and Remarry!”

The Osborne family tree was prominently displayed in the hallway like a proud, sly joke on English heraldry. No blue blood there—but publicans on both sides of the family from the nineteenth century, with domestic servants, a dressmaker, a billiard-marker, brass polisher, timber merchant and several carpenters stretching back to the eighteenth. Osborne’s Welsh roots go back to his great-great- grandfather—a carpenter who crossed the Bristol Channel from North Devon to live in Newport, Monmouthshire, in the early nineteenth century. “Osborne” is a popular Welsh surname stretching back to the thirteenth century.

An Elisabeth Frink sculpture of an alarming harbinger bird stood guard like a totem in the hallway outside the drawing room—the best room—with its grand floor-length windows looking out onto the landscape. The statuette of Osborne’s 1963 Oscar for the screen adaptation of Tom Jones stood on a small corner table looking in its neutered, absurdly golden way as incongruous as the framed photograph next to it of George Devine in drag. Devine, whom Osborne worshipped, was the founding artistic director of the English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre and appeared onstage as a fetching Queen Alexandra during the notorious drag ball scene of A Patriot for Me. “You know,” he said to Osborne one night in his dressing room as he puffed on his pipe in his garter belt and high heels, “the price of lipstick today really is outrageous.”

From the Hardcover edition.

The Hurst

I may be a poor playwright, but I have the best view in England—

John Osborne at home in Shropshire

As I remember it now, when I first visited Osborne’s house in Clun, deep in the Shropshire hills, I was struck by its remoteness from what he called the kulcher of London. Though a dramatist may write as well in the tweedy shires as in literary Hampstead, it was as if he had fled all contact with the theatre that had been his life. He moved to Shropshire for good with his wife, Helen, in 1986 and the Clun valley with its surly sheep, close to the Welsh border in Housman country, is about as far from the metropolis as you can get without actually leaving England.

Clunton and Clunbury; Clungunford and Clun

Are the quietest places under the sun

—A. E. Housman, not at his best.

The famously urban dramatist was a countryman at heart who loved the place as his own chunk of ancient England, unless, that is, he was the play-acting poseur some took him for. He began as an actor, after all. What role, then, was he playing? Former Angry Young Man now morphed into curmudgeonly country squire? The noncomformist clamped as brawling Tory blimp? The ex-playwright? He had taken to signing his name “John Osborne, ex-playwright” even as he continued struggling with new plays in the wreckage of a life ruled by disorder and passion. Had he become that sentimental relic or absurdist thing, an English Gentleman? But Osborne, everyone knew, wasn’t a gentleman.

He was almost a gentleman. Scholarly literary critics attributed the title of his second volume of autobiography in 1991, Almost a Gentleman, to Cardinal Newman. Osborne had quoted from Newman’s The Idea of a University, 1852, in a learned epigraph: “It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain.” The problem with scholarly critics, however, is they don’t know their Music Hall. He didn’t owe the title to the exalted source of Newman, but more typically to the low comedy of one of Music Hall’s great solo warriors in comic danger known as Billy “Almost a Gentleman” Bennett.

A rousing poetic monologuist—“Well, it rhymes!”—Bennett reached the height of his considerable fame in the 1920s and ’30s. He was billed as “Almost a Gentleman.” His signature tune, “She Was Poor, But She Was Honest,” was renowned:

It’s the same the whole world over,

It’s the poor what gets the blame.

It’s the rich what gets the pleasure,

Isn’t it a blooming shame?

Osborne was no intellectual and Billy Bennett’s sunny vulgarity and pathos appealed to his taste. Bennett also created surreal acts entitled “Almost a Ballet Dancer” and “Almost Napoleon.” But it was “Almost a Gentleman” that made his name as he nobly played his part in ill-fitting evening dress and army boots. Thus Osborne posed stagily for a Lord Snowdon portrait for the cover of his autobiography in full country gentleman regalia—tweed jacket, buttoned waistcoat, fob watch, umbrella—all topped off nicely with the prop of a flat cap, traditional emblem of the working man. But if we look closer at the Snowdon picture, this image of the sixty-year- old dramatist is too raffish to be gentlemanly. The tweed cap is at a jaunty angle, there’s a dandy in the foppish, velvet bow tie, a showman in the long silk scarf draped over-casually round his shoulders. The opal signet ring he’s wearing suggests an actor- manager of the old school or perhaps a refined antiques dealer of a certain age. The distinguished film and theatre director Lindsay Anderson, known to Osborne as “The Singing Nun,” wondered if he was auditioning in the photograph for the role of Archie Rice’s old Edwardian dad. But his chin is up, as Anderson shrewdly noted, his expression still defiant, promising combat outside the Queensberry rules.

I was visiting the Osborne home, The Hurst, three years after he died on Christmas Eve, 1994, and as the car nosed up the long driveway that winds through neighbouring farmland I was unprepared for the grandeur of the 1812 manor house on the hill. The Hurst with its twenty rooms is set in handsome, stony isolation on thirty acres with well-trodden garden paths through woodland and orchard, a clock tower, various outbuildings, and a village-size pond big enough for its own island and plentiful trout.

I had anticipated something much less impressive even by Osborne’s standards—a cottage perhaps, or country pile overgrown with weeds. I’d heard that he had been in financial trouble for years, and was all but bankrupt when he died. In fact, local tradesmen had cut off his credit at one low point and he was left sleepless with anxiety that the house itself would be foreclosed on by the bank.

Two years before his death, three of his friends had grown so alarmed at the state of his finances, they organised a meeting to try to help him. There were various plans to sell the copyrights of his plays in return for a lump sum to settle debts. But one of the problems they hoped to solve was the fact that Osborne spent more than he earned. Playwright David Hare, theatre producer Robert Fox, and Robert McCrum, Osborne’s editor at Faber & Faber, met him at the Cadogan Hotel in Belgravia where he stayed when visiting London. He nicknamed it “Oscar’s Place” (Oscar Wilde was arrested there). But he was a proud man and the meeting with the three do-gooders went disastrously.

“You might try cutting back a bit on the champagne, John,” one of them had the temerity to suggest.

It was like asking someone to breathe less oxygen. Osborne and champagne were as inseparable as Fortnum & Mason. He drank it from a silver tankard—“like white wine,” as his third wife, Penelope Gilliatt, observed dryly. When in younger days he shared a flat with the director Tony Richardson, the only food they ever had in the place was a fridge full of Dom Perignon and oranges. When he was married to wife number four, Jill Bennett, they kept a fridge in the bedroom to save them the inconvenience of going downstairs to fetch the “shampoo.”

On summer days at The Hurst, he greeted guests dressed in a boater and striped blazer like a rep actor in a touring production of The Boy Friend as he held up a bottle of champagne in welcome.

“And I can tell you this,” he protested at the meeting, flooring them all. “I’m not getting rid of the horses!”

His two trusty hacks, as indestructible as tractors rusting in a barn, had been in the family for years, along with two donkeys and three dogs. But broke he was. “Hang onto the house, if you possibly can,” he said to his wife during the last days.

“Welcome to Chateau Calamity,” she said with a smile when I arrived, and offered me champagne.

It had come as a surprise when Helen Osborne telephoned me unexpectedly in New York, where I’ve lived for many years, and said with typical diffidence, “I don’t suppose you would be interested in writing John’s authorized biography?”

My first instinct was to run. “It’s certainly an honour to be asked,” I said, playing for time.

“Well, you don’t sound very honoured,” she replied, which was also typical.

I first knew her when she was Helen Dawson, the admired arts editor and sometime drama critic of the Observer in the heyday of David Astor’s editorship during the 1960s. I joined the paper soon after her, and often sought out her company as she beavered away behind filing cabinets. Osborne famously dismissed critics as treacherous parasites, but he married two of them—Helen Dawson and film critic Penelope Gilliatt. Then again, he said of actresses that they made impossible mistresses and even worse wives, and he married three—his first wife, actress Pamela Lane; second wife, Mary Ure; and fourth wife, Jill Bennett.

His fifth—or “Numero Cinque” as Osborne often called her—was the only one of his wives, it’s widely believed, to make him happy. They were married on 2 June 1978, and lived together for eighteen years. They were apart for no more than a few days during all that time.

It was through my friendship with Helen at the Observer that I eventually got to know Osborne a little, though I had met him earlier when his 1968 play The Hotel in Amsterdam with Paul Scofield was playing in Brighton—Osborne’s favourite place on earth, lost paradise of the dirty weekend. “Oh blimey—not you again!” the stage carpenter would greet him, whenever one of his plays opened at Brighton’s Theatre Royal. He looked elegant and young when we met that day. He said hello in a slightly camp, relaxed drawl, and he clearly didn’t give a damn. I remember envying him a bit. He was on top of the world, or so it seemed.

Soon afterwards, I met him again and he looked at me suspiciously. I was wearing Paul Scofield’s suit from the play.

My first wife designed the costumes for two of Osborne’s plays, and The Hotel in Amsterdam was one of them. Scofield’s suit had been specially made for the production by Doug Hayward, the bespoke Savile Row tailor to the stars. Hayward was tailor to the dandyish John Osborne. The suit itself was an amazing hunter green with black brocade round the lapels. (This was the Sixties.) But Scofield didn’t actually wear it in the play because it didn’t suit him. It was therefore up for grabs.

Although it was a little tight on me, I was proudly wearing it, after a decent interval, when I bumped into Osborne at Don Luigi’s restaurant in the King’s Road.

“And how are yew?” he asked, still looking doubtfully at me in the treasured suit.

I subsequently met him socially on several occasions and each time he struck me as the very opposite of his combative image. I found him a gentle man, and almost excessively polite. He was gossipy and fun, and highly instinctive. And there were times when he seemed surprisingly vulnerable—as if camouflaging some sadness.

I saw him again when he and Helen were in New York during the Eighties. The city still enchanted him. He had first visited Manhattan in his meteoric twenties when two of his plays were running simultaneously on Broadway (Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer). One night, we were walking along Broadway back to the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street, where he always stayed, when he began to lean forward peculiarly like a strange version of Groucho Marx in a strong headwind. He told me it was the best way to walk, particularly over long distances, and called it “The Countryman Tramp’s Walk.” It had been taught to him by his eccentric grandfather. And now he taught it to me. We tried it out together, doing the Countryman Tramp’s Walk along the Great White Way, and even New Yorkers, who’ve seen everything, looked curious as we surged past them.

The last time I saw him was when he visited New York again with Helen in September 1984. He was then fifty-four and his plays were out of fashion. But they were a relaxed couple, enjoying each other’s company —enjoying treats. He greeted me with an affectionate, whiskery kiss smack on the lips, which pleased us both, like sharing a secret.

That night, the three of us went to the Algonquin’s Oak Room for a jolly supper and cabaret, and drank so much champagne I had to go to bed for two days afterwards. When the cabaret finished, the pianist went to shake the hands of the audience, as entertainers in New York like to do, and Osborne looked suddenly embarrassed. “He won’t remember me,” he murmured disconsolately.

“Welcome back, Mr. Osborne,” the pianist greeted him, shaking his hand warmly.

“Well, thank you very much!” he replied, beaming.

The evening went swimmingly after that. We talked about the great Music Hall artists who had influenced him. He saw them as a warrior class of gods and heroes even in pitiful failure like Archie Rice in The Entertainer. When I told him that I’d seen the wrecked comic genius Max Wall perform the same hilarious act six times, he was mightily impressed. He had cast the legendary, old comic as Archie in his own production of The Entertainer during the Seventies. To his delight, he remembered that Max asked him during rehearsals if he could add just one line to the famous play. The intrigued, but wary, Osborne replied, “Of course, Max. But what’s the line?”

It was, “Take my wife, puh-leeze!”

Osborne could scarcely stop laughing. (And the line went in the play.)

Now, over a decade later, I was visiting his widow for the first of several visits to begin work on his biography.

Two slobbering chocolate labradors flattened me against the front door of The Hurst in muddy confusion. “Down boys!” Helen Osborne ordered. But the boys, when up, seemed practically her size. At only five-foot-two, she was petite. (Her husband was tall and rangy, over six feet.)

Once inside this well-lit place, however, it was clear that, countryman or no, only a man of the theatre had once lived there. The hallway was crowded with framed posters of several of the plays. Leonard Rosoman paintings of the 1965 production of A Patriot for Me ascended the staircase. Surprisingly corny cushions spelt out embroidered messages from a bench: “You ARE leaving on Sunday, aren’t you?” “It is difficult to soar like an eagle when you’re surrounded by turkeys.” “Eat Drink and Remarry!”

The Osborne family tree was prominently displayed in the hallway like a proud, sly joke on English heraldry. No blue blood there—but publicans on both sides of the family from the nineteenth century, with domestic servants, a dressmaker, a billiard-marker, brass polisher, timber merchant and several carpenters stretching back to the eighteenth. Osborne’s Welsh roots go back to his great-great- grandfather—a carpenter who crossed the Bristol Channel from North Devon to live in Newport, Monmouthshire, in the early nineteenth century. “Osborne” is a popular Welsh surname stretching back to the thirteenth century.

An Elisabeth Frink sculpture of an alarming harbinger bird stood guard like a totem in the hallway outside the drawing room—the best room—with its grand floor-length windows looking out onto the landscape. The statuette of Osborne’s 1963 Oscar for the screen adaptation of Tom Jones stood on a small corner table looking in its neutered, absurdly golden way as incongruous as the framed photograph next to it of George Devine in drag. Devine, whom Osborne worshipped, was the founding artistic director of the English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre and appeared onstage as a fetching Queen Alexandra during the notorious drag ball scene of A Patriot for Me. “You know,” he said to Osborne one night in his dressing room as he puffed on his pipe in his garter belt and high heels, “the price of lipstick today really is outrageous.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Miraculous. . . . A model of what a literary biography ought to be. . . . The Osborne who emerges from these pages is a character of almost Shakespearean dimensions, grand as Falstaff, volatile as Hamlet, mad as Lear.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer"A terrific story. . . . An appealing, rollicking portrait. . . . The best literary biography I have read in a long time." —Harold Evans, The Wall Street Journal"I cannot recall a biography that was so amusing and intense. . . . If there is going to be a better-written, more entertaining, or more sharply observed performance this year, I'll be mighty surprised." —Carl Rollyson, The New York Sun