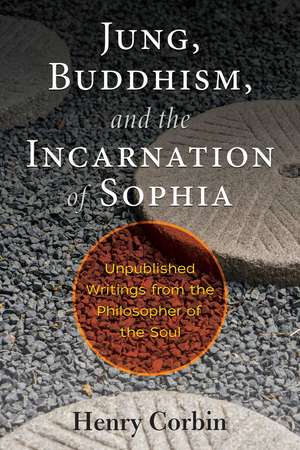

Jung, Buddhism, and the Incarnation of Sophia: Unpublished Writings from the Philosopher of the Soul

Autor Henry Corbinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 21 mar 2019

Examines the work of Carl Jung in relation to Eastern religion, the wisdom teachings of the Sophia, Sufi mysticism, and visionary spirituality

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was one of the most important French philosophers and orientalists of the 20th century. In this collection of previously unpublished writings, Corbin examines the work of Carl Jung in relationship to the deep spiritual traditions of Eastern religion, the esoteric wisdom teachings of Sophia, the transformational symbolism of alchemy, and Sufi mysticism.

Looking at the many methods of inner exploration in the East, including the path of the Sufi and Taoist alchemy, Corbin reveals how the modern Western world does not have its own equivalent except in psychotherapy. Expanding Jung’s findings in light of his own studies of Gnostic and esoteric Islamic traditions, he offers a unique insight into the spiritual values underlying Jung’s psychoanalytic theories. Corbin analyzes Jung’s works on Buddhism, providing his own understanding of the tradition and its relationship to Sufi mysticism, and explores the role of the Gnostic Sophia with respect to Jung’s most controversial essay, “Answer to Job.”

Explaining how Islamic fundamentalists have turned their back on the mystic traditions of Sufism, Corbin reveals how totalitarianism of all kinds threatens the transformative power of the imagination and the transcendent reality of the individual soul.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was one of the most important French philosophers and orientalists of the 20th century. In this collection of previously unpublished writings, Corbin examines the work of Carl Jung in relationship to the deep spiritual traditions of Eastern religion, the esoteric wisdom teachings of Sophia, the transformational symbolism of alchemy, and Sufi mysticism.

Looking at the many methods of inner exploration in the East, including the path of the Sufi and Taoist alchemy, Corbin reveals how the modern Western world does not have its own equivalent except in psychotherapy. Expanding Jung’s findings in light of his own studies of Gnostic and esoteric Islamic traditions, he offers a unique insight into the spiritual values underlying Jung’s psychoanalytic theories. Corbin analyzes Jung’s works on Buddhism, providing his own understanding of the tradition and its relationship to Sufi mysticism, and explores the role of the Gnostic Sophia with respect to Jung’s most controversial essay, “Answer to Job.”

Explaining how Islamic fundamentalists have turned their back on the mystic traditions of Sufism, Corbin reveals how totalitarianism of all kinds threatens the transformative power of the imagination and the transcendent reality of the individual soul.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was one of the most important French philosophers and orientalists of the 20th century. In this collection of previously unpublished writings, Corbin examines the work of Carl Jung in relationship to the deep spiritual traditions of Eastern religion, the esoteric wisdom teachings of Sophia, the transformational symbolism of alchemy, and Sufi mysticism.

Looking at the many methods of inner exploration in the East, including the path of the Sufi and Taoist alchemy, Corbin reveals how the modern Western world does not have its own equivalent except in psychotherapy. Expanding Jung’s findings in light of his own studies of Gnostic and esoteric Islamic traditions, he offers a unique insight into the spiritual values underlying Jung’s psychoanalytic theories. Corbin analyzes Jung’s works on Buddhism, providing his own understanding of the tradition and its relationship to Sufi mysticism, and explores the role of the Gnostic Sophia with respect to Jung’s most controversial essay, “Answer to Job.”

Explaining how Islamic fundamentalists have turned their back on the mystic traditions of Sufism, Corbin reveals how totalitarianism of all kinds threatens the transformative power of the imagination and the transcendent reality of the individual soul.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was one of the most important French philosophers and orientalists of the 20th century. In this collection of previously unpublished writings, Corbin examines the work of Carl Jung in relationship to the deep spiritual traditions of Eastern religion, the esoteric wisdom teachings of Sophia, the transformational symbolism of alchemy, and Sufi mysticism.

Looking at the many methods of inner exploration in the East, including the path of the Sufi and Taoist alchemy, Corbin reveals how the modern Western world does not have its own equivalent except in psychotherapy. Expanding Jung’s findings in light of his own studies of Gnostic and esoteric Islamic traditions, he offers a unique insight into the spiritual values underlying Jung’s psychoanalytic theories. Corbin analyzes Jung’s works on Buddhism, providing his own understanding of the tradition and its relationship to Sufi mysticism, and explores the role of the Gnostic Sophia with respect to Jung’s most controversial essay, “Answer to Job.”

Explaining how Islamic fundamentalists have turned their back on the mystic traditions of Sufism, Corbin reveals how totalitarianism of all kinds threatens the transformative power of the imagination and the transcendent reality of the individual soul.

Preț: 95.33 lei

Preț vechi: 128.45 lei

-26% Nou

Puncte Express: 143

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.24€ • 18.98$ • 15.06£

18.24€ • 18.98$ • 15.06£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781620557396

ISBN-10: 1620557398

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1620557398

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was one of the most important French philosophers and orientalists of the 20th century as well as one of the most influential scholars of Islamic mysticism. A former professor of Islam and Islamic Philosophy at the Sorbonne and the University of Tehran, Corbin was the author of several books, including Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn’Arab.

Extras

I

Zen (on The Book of Great Deliverance)

An acquaintance with Zen Buddhism is accessible to Western readers in part thanks to the translations and admirable studies by Suzuki. We have all seen clearly that Zen is neither a psychology nor a philosophy in the sense that we usually give those words. The shock that Zen intends, operating within a soul--which then is transformed--comes to fruition in a totally irrational process, unconnected to the data and provisions of logic and dialectic. The implications of this process, and the discovery that on completion creates the initial reality of a new mode of being and perception are specifically what brings the Zen school of Buddhism and Jung’s psychotherapy into harmonious relationship. We would like to take up this harmony here as the initial theme of our “paraphrase.”

From the outset, we might wonder if such a theme doesn’t tend toward a contradictory initiative. What forms the essence and raison d’être of Zen is the central intuition that is designated by the Japanese term satori, which we can attempt to translate by “enlightenment.” Here we have a mysterium ineffabile. Between the famous and very strange anecdotes with their often absurd wording that Zen offers for contemplation by its adepts, and the enlightenment that blossoms abruptly and brutally, there yawns an abyss that cannot be bridged with rational contemplation or explanation. As Jung says in his Gesammelte Werke, that all you can do is to maneuver through the neighboring proximity and the maneuvering is all the more difficult because you are then going counter to the spirit of Zen. The impression that seems to emerge is one of an experience a nihilo, that corresponds to an inner movement of what in astrology or cosmology is called creatio ex nihilo. What rejects this, setting itself in opposition to emanationism, is specifically the train of thought that begins by positing something based on which there would be derived or emanate, necessarily, all the superabundance of being. This being said, we do not mean to imply that the creationist doctrines were aware of this--far from it. But instead: the legendary brutality with which certain famous Zen masters replied to their students’ questions by hitting them with their stick or their fist, responds to the necessity to create pure, naked fact, before and beyond all affirmation and all negation, before and beyond all pre-existing material support on which it might repose. The explosion of an encounter, the injunction Show me--or discover--or study--your face as it was before you were born, before the creation of the world. Absolute initium. Urerfahrung. Experience that is ab initio and ab imo, initial and of the void. That which supports the intuitive understanding of what the void (śūnya) is—this concept about which so many misunderstandings have arisen and which has led so superficially to talk of Buddhist “nihilism.” It is a question of expunging from consciousness all representations of objects, the assemblage or configuration of which are imposed on consciousness as data that it sustains, as well as expunging along with those representations all the laws of physics and history. One must put oneself back to the origin, pierce through to the mind whose own law alone assembled these objects and their representations. And then, finding this original Void, which is absolute power, the principle of contradiction will also have been surmounted, since things and beings once again will be there but in a transformed sense.

This is the sense of the very striking image used by one of the masters whom Suzuki quotes, “Before someone studies Zen, for him, mountains are mountains and waters are waters. Once he has managed to penetrate into the truth of Zen through the teaching that a good master provides for him, then mountains are no longer mountains and waters are no longer waters. But when he has truly attained the place of rest (that is, obtained satori), then for him, once again, mountains are mountains and waters are waters.”

The man who confronted the world of objects and the reality of objects was a man who was full of himself. What was this himself of which he was full and how, specifically, by giving way to illusion, does he “egoify” this “I?” How does he make it into ego by succumbing to the illusion of objects? An “I” that clearly has not been and could not have been set aside by a rational negation (that is, a negative, logical operation).

“If I came to see you with nothing, what would you say?”

“Drop it!”

“But I just told you I have nothing! How can I drop it?”

“So, pick it up!”

Because this nothing about which he has been thinking is still something affected by a negative sign, a nothing that is still rational, decreed by logic. It is not the Void that is referred to by the teaching of the Great Vehicle which is attained, “realized” through a shattering of the “I” that clamps onto rational consciousness--the consciousness that is like a blinding and a limitation of consciousness itself. The experience of satori is the emancipation from that, and, by discovering your face before the initial instant of the creation of things (where all things are created in front of you and through you the pure Thus), it gives you access to the Pure Land of transcendent consciousness. There we have a totality of the consciousness of life. “The moon of the mind includes the whole universe: it is cosmic life and cosmic mind, and simultaneously individual life and individual mind.”

Zen (on The Book of Great Deliverance)

An acquaintance with Zen Buddhism is accessible to Western readers in part thanks to the translations and admirable studies by Suzuki. We have all seen clearly that Zen is neither a psychology nor a philosophy in the sense that we usually give those words. The shock that Zen intends, operating within a soul--which then is transformed--comes to fruition in a totally irrational process, unconnected to the data and provisions of logic and dialectic. The implications of this process, and the discovery that on completion creates the initial reality of a new mode of being and perception are specifically what brings the Zen school of Buddhism and Jung’s psychotherapy into harmonious relationship. We would like to take up this harmony here as the initial theme of our “paraphrase.”

From the outset, we might wonder if such a theme doesn’t tend toward a contradictory initiative. What forms the essence and raison d’être of Zen is the central intuition that is designated by the Japanese term satori, which we can attempt to translate by “enlightenment.” Here we have a mysterium ineffabile. Between the famous and very strange anecdotes with their often absurd wording that Zen offers for contemplation by its adepts, and the enlightenment that blossoms abruptly and brutally, there yawns an abyss that cannot be bridged with rational contemplation or explanation. As Jung says in his Gesammelte Werke, that all you can do is to maneuver through the neighboring proximity and the maneuvering is all the more difficult because you are then going counter to the spirit of Zen. The impression that seems to emerge is one of an experience a nihilo, that corresponds to an inner movement of what in astrology or cosmology is called creatio ex nihilo. What rejects this, setting itself in opposition to emanationism, is specifically the train of thought that begins by positing something based on which there would be derived or emanate, necessarily, all the superabundance of being. This being said, we do not mean to imply that the creationist doctrines were aware of this--far from it. But instead: the legendary brutality with which certain famous Zen masters replied to their students’ questions by hitting them with their stick or their fist, responds to the necessity to create pure, naked fact, before and beyond all affirmation and all negation, before and beyond all pre-existing material support on which it might repose. The explosion of an encounter, the injunction Show me--or discover--or study--your face as it was before you were born, before the creation of the world. Absolute initium. Urerfahrung. Experience that is ab initio and ab imo, initial and of the void. That which supports the intuitive understanding of what the void (śūnya) is—this concept about which so many misunderstandings have arisen and which has led so superficially to talk of Buddhist “nihilism.” It is a question of expunging from consciousness all representations of objects, the assemblage or configuration of which are imposed on consciousness as data that it sustains, as well as expunging along with those representations all the laws of physics and history. One must put oneself back to the origin, pierce through to the mind whose own law alone assembled these objects and their representations. And then, finding this original Void, which is absolute power, the principle of contradiction will also have been surmounted, since things and beings once again will be there but in a transformed sense.

This is the sense of the very striking image used by one of the masters whom Suzuki quotes, “Before someone studies Zen, for him, mountains are mountains and waters are waters. Once he has managed to penetrate into the truth of Zen through the teaching that a good master provides for him, then mountains are no longer mountains and waters are no longer waters. But when he has truly attained the place of rest (that is, obtained satori), then for him, once again, mountains are mountains and waters are waters.”

The man who confronted the world of objects and the reality of objects was a man who was full of himself. What was this himself of which he was full and how, specifically, by giving way to illusion, does he “egoify” this “I?” How does he make it into ego by succumbing to the illusion of objects? An “I” that clearly has not been and could not have been set aside by a rational negation (that is, a negative, logical operation).

“If I came to see you with nothing, what would you say?”

“Drop it!”

“But I just told you I have nothing! How can I drop it?”

“So, pick it up!”

Because this nothing about which he has been thinking is still something affected by a negative sign, a nothing that is still rational, decreed by logic. It is not the Void that is referred to by the teaching of the Great Vehicle which is attained, “realized” through a shattering of the “I” that clamps onto rational consciousness--the consciousness that is like a blinding and a limitation of consciousness itself. The experience of satori is the emancipation from that, and, by discovering your face before the initial instant of the creation of things (where all things are created in front of you and through you the pure Thus), it gives you access to the Pure Land of transcendent consciousness. There we have a totality of the consciousness of life. “The moon of the mind includes the whole universe: it is cosmic life and cosmic mind, and simultaneously individual life and individual mind.”

Cuprins

Preface from the Editor

Henry Corbin, Philosopher of the Soul

by Michel Cazenave

PART I

CARL GUSTAV JUNG AND BUDDHISM

Publisher’s Note on Sources and Corbin’s Commentary

Introduction to Part I

1. Zen (on The Book of Great Deliverance)

2. Pure Land (on La Psychologie de la méditation orientale)

3. The Tibetan Book of the Dead (on the Bardo Thödol)

4. Taoist Alchemy (on The Secret of the Golden Flower)

5. Conclusion: The Self and Sophia

PART II

Answer to Job

1. Eternal Sophia

2. Postscript to Answer to Job

Appendices

1. Letters to Mrs. Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn

2. Sophia Æterna

3. “Eranos”

Angel Logic by Michel Cazenave

Bibliography

Index

Henry Corbin, Philosopher of the Soul

by Michel Cazenave

PART I

CARL GUSTAV JUNG AND BUDDHISM

Publisher’s Note on Sources and Corbin’s Commentary

Introduction to Part I

1. Zen (on The Book of Great Deliverance)

2. Pure Land (on La Psychologie de la méditation orientale)

3. The Tibetan Book of the Dead (on the Bardo Thödol)

4. Taoist Alchemy (on The Secret of the Golden Flower)

5. Conclusion: The Self and Sophia

PART II

Answer to Job

1. Eternal Sophia

2. Postscript to Answer to Job

Appendices

1. Letters to Mrs. Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn

2. Sophia Æterna

3. “Eranos”

Angel Logic by Michel Cazenave

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“That Henry Corbin was one of the great religious thinkers of the 20th century will be apparent to all who delve into this brilliant collection of his previously unpublished writings on Carl Jung and Buddhism, the gnostic Sophia, and Sufism. Corbin’s insights into the profound roots of Jung’s teachings make this essential reading for those who ponder the ties that bind psychology and spirituality and all the great religious traditions to one another.”

“Jung, Buddhism, and the Incarnation of Sophia is where two astounding explorers of the inner cosmos, Henri Corbin and Carl Jung, meet in their insights--an intriguing octagon of mirrors surrounding the illuminated soul.”

"Delivered on all accounts in offering me valuable insights into the complexities of the psycho-spiritual nature of Gnostic and Buddhist practices, as well as filling my coffers with a simplicity that inspires a more contemplative approach in the deepening of my own spiritual and philosophical beliefs."

“Jung, Buddhism, and the Incarnation of Sophia is where two astounding explorers of the inner cosmos, Henri Corbin and Carl Jung, meet in their insights--an intriguing octagon of mirrors surrounding the illuminated soul.”

"Delivered on all accounts in offering me valuable insights into the complexities of the psycho-spiritual nature of Gnostic and Buddhist practices, as well as filling my coffers with a simplicity that inspires a more contemplative approach in the deepening of my own spiritual and philosophical beliefs."

Descriere

Examines the work of Carl Jung in relation to Eastern religion, the wisdom teachings of the Sophia, Sufi mysticism, and visionary spirituality