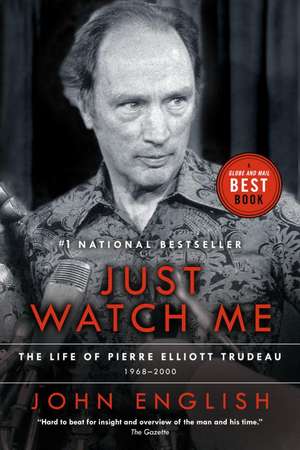

Just Watch Me: 1968-2000

Autor John Englishen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2010

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Governor General's Literary Awards (2010), Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing (2009), RBC Taylor Prize (2010)

His life is one of Canada’s most engrossing stories. John English reveals how for Trudeau style was as important as substance, and how the controversial public figure intertwined with the charismatic private man and committed father. He traces Trudeau’s deep friendships (with women especially, many of them talented artists, like Barbra Streisand) and bitter enmities; his marriage and family tragedy. He illuminates his strengths and weaknesses — from Trudeaumania to political disenchantment, from his electrifying response to the kidnappings during the October Crisis, to his all-important patriation of the Canadian Constitution, and his evolution to influential elder statesman.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 169.67 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 255

Preț estimativ în valută:

32.47€ • 33.99$ • 26.86£

32.47€ • 33.99$ • 26.86£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780676975246

ISBN-10: 0676975240

Pagini: 832

Ilustrații: 61 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 168 x 228 x 45 mm

Greutate: 0.81 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0676975240

Pagini: 832

Ilustrații: 61 B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 168 x 228 x 45 mm

Greutate: 0.81 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

John English is Professor of History, University of Waterloo. Citizen of the World was a multi-award winner and a Globe and Mail Best Book.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

TAKING POWER

The champagne sparkled, the boyish smile lingered as Pierre Elliott Trudeau waved to the cheering crowd at the Liberal convention in 1968. On April 6, a Saturday afternoon, the forty-eight-year-old Montrealer and Canada's reformist minister of justice was elected on the fourth ballot as the seventh Liberal leader since Confederation. His victory meant that he would become the sixth Liberal prime minister of Canada. Donning the mantle of Laurier and King, St. Laurent and Pearson, Trudeau prepared to address not only the delegates at Ottawa's Civic Centre but also the curious nation beyond, which, gathered around mostly black-and-white television sets, was about to witness the birth of "Trudeaumania." Whatever the meaning of the phenomenon, the evening seemed historic, for Trudeau would be the first Canadian prime minister born in the twentieth century, the youngest prime minister since the 1920s, and with fewer than three years in the House of Commons, the least experienced prime minister in Canada's history.

The Trudeau crowd was young but so were the times. Trudeau had begun his victorious campaign to capture the Prime Minister's Office just as the Beatles launched their Magical Mystery Tour and the musical Hair declared its discovery of sex, drugs, and rock and roll and headed for Broadway. The year blended magic and political shock as the fringe and the alternative merged with the mainstream. At the end of January, the Viet Cong had stunned American forces in Vietnam with its Tet offensive, and the American presidency of Lyndon Johnson suddenly began to crumble. Richard Nixon, the old Cold Warrior, returned from the political wilderness to become a serious Republican contender for the presidency as Democrats jostled to succeed Johnson. And the American dream had become a nightmare. That vision of promise, embodied in the young and eloquent John F. Kennedy, had entranced Canadians at the beginning of the decade, but Kennedy was gone, and on Thursday, April 4, the day before the Liberal leadership convention began, James Earl Ray had gunned down the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., as the civil rights leader stood on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee. The eruption of violence in America's largest cities following King's assassination shared front-page headlines in Canada's newspapers with the convention triumph of Pierre Trudeau.

The contrast was striking. Canada suddenly seemed different (cool in the argot of the day), a "peaceable kingdom" as some now called it. In this setting the candidacy of the parliamentarian of only three years became politically intriguing. His style and stance were unique in the history of Canada: an erstwhile socialist who cared what French intellectuals wrote, wore shoes without socks and jackets without ties and still looked elegant, drove the perfect Mercedes 300SL convertible, and flirted boldly with women a generation younger. That April weekend the American counterparts of the youth at the Ottawa Civic Centre were angrily demonstrating in the streets or on campuses. Bob Rae, then a hairy, rumpled student radical at the University of Toronto, later recalled how he went off to that convention, drawn to Trudeau's incisiveness, wit, "belief that ideas mattered in politics," and most of all, his "style." His roommate and fellow student activist, Michael Ignatieff, joined the Trudeau team and claimed, forty years later, that politics were never again as exciting for him as during those heady days in the spring of 1968. John Turner supporter Bruce Allen Powe took his thirteen-year-old son to the convention, where Bruce Jr. defied his father's allegiance, hid his Trudeau buttons beneath his jacket, and began a lifelong infatuation.

The infatuation was infectious. After the convention formally ended, Trudeau's supporters and thousands of others crammed into the new Skyline Hotel in downtown Ottawa, where the "curvaceous" Diamond Lil performed one of her livelier dances between two Trudeau campaign posters. Throngs of miniskirted teenagers screamed a welcome to the new leader, and older followers sang "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow." "Let's party tonight," a beaming Trudeau told the crowd, "but remember that Monday the party is over."

Before long, Trudeau spotted Bob Rae's striking young sister, Jennifer, across the room, and fastening his penetrating blue eyes on her, he came close and whispered, "Will you go out with me sometime?" She later did, but he also remembered the fetching teenager who had spurned him in Tahiti the previous December but had willingly accepted his eager kiss that afternoon as he left the convention floor. When reporters asked Margaret Sinclair, the daughter of a former Liberal Cabinet minister, "Have you eyes for Trudeau? Are you a girlfriend?" she replied, "No, I have eyes for him only as prime minister." The office had already brought Trudeau unanticipated benefits, and for the first time since Laurier, a Canadian prime minister was sexy.

Trudeau knew that public expectations were too high, and he moved quickly to dampen them in his acceptance speech at the convention and at his next appearance. The acceptance speech reads poorly, but content mattered little, as Trudeau's words were submerged in the froth of victory. On April 7, the day after he became leader, Trudeau held a nationally televised press conference. Sporting the fresh red rose that had already become his trademark, he praised his opponents—particularly Robert Winters, who had finished second—and said he was considering how they would fit into his Cabinet. To the surprise of some commentators, he indicated there was no need for an immediate election. Then, unexpectedly, he denied that he was a radical or a "man of the left." "I am," he declared, "essentially a pragmatist." The comment confused many observers.

Not long before, Trudeau had proudly declared himself a leftist. Evidence of his "radicalism" and left-wing views abounded in old newspaper clippings; in the memories of many who knew him; and in Cité libre, the journal he had edited in the 1950s. New Democratic Party leader Tommy Douglas recalled trying to recruit Trudeau as a socialist candidate only a few years earlier. Trudeau knew that his future success rested on reassurance, which paradoxically required ambiguity, rather than strong assertions of principle. At the convention he'd talked about the "Just Society" he intended to construct, but its contours were thinly sketched and its foundations, apart from a commitment to the rights of individuals to make their own decisions, were barely visible.

Ambiguity or, perhaps more accurately, mystery was apparently alluring. Even the Spectator, the British conservative magazine so often given to cynical observations about the oldest dominion, succumbed to the enthusiasm surrounding Trudeau: "It was as if Canada had come of age, as if he himself single handedly would catapult the country into the brilliant sunshine of the late 20th century from the stagnant swamp of traditionalism and mediocrity in which Canadian politics had been bogged down for years." In the spring of 1968, an intrigued William Shawn, the celebrated editor of the New Yorker, commissioned Edith Iglauer to write a long article on Canada's new prime minister. It took a year to complete, but it remains the best portrait of Trudeau as he took power and shaped his private self to the new demands of public life.

Leading Canadian journalists could not resist his charm, and many cast objectivity to the winds and signed a petition endorsing Trudeau. Historian Ramsay Cook, a traditional supporter of the New Democratic Party but a Trudeau speechwriter in 1968, retains a scrap of paper from that year which reads: "Pierre Trudeau is a good shit (merde)." It was signed by eminent leftist journalist June Callwood and her sportswriter husband, Trent Frayne; Maclean's editor Peter Gzowski and his wife, Jenny; and the brash young interviewer Barbara Frum. Peter C. Newman, the talented and bestselling political journalist at the Toronto Star, commented, "The whole house of clichés constructed by generations of politicians is demolished as soon as [Trudeau] begins to speak."

—

Trudeau's freshness seemed to free him from the dense political foliage and sombre shades that had darkened Ottawa in the mid-1960s, when Canada, in Newman's famous term, suffered from political "distemper." Two veterans of the First World War, John Diefenbaker and Lester Pearson, fought pitched battles that both bored and infuriated Canadians. The Conservatives rejected Diefenbaker in a bitter convention in 1967 and turned to the Nova Scotia premier, Robert Stanfield, whose laconic style and careful ways contrasted strongly with the fiery Saskatchewan populist. The seventy-year-old Pearson stepped aside more gracefully just before Christmas 1967, when the polls were showing that Stanfield would trounce the Liberals should the government fall. The Liberal minority tottered as the candidates for Pearson's succession took their places in the winter of 1968. By that time Pearson had become convinced that his successor should be Pierre Trudeau, who had been his parliamentary secretary but had remained personally distant. Pearson told a close friend that "ice water" ran through Trudeau's veins. Still, his successor had to be a francophone, he thought, and Trudeau's intellect, his presence, and even his cold rationality made him the logical choice. Pearson's wife, Maryon, was openly smitten with the charm Trudeau so deftly and consciously revealed to women, and her affection for her husband's successor was obvious to all. A cartoonist wrote a caption on a photograph above Maryon as she gazed fondly at Trudeau: "Of course, Pierre, you realize that if you win, I go with the job." She didn't, but the Victorian mansion on Sussex Drive did. It was the bachelor Pierre Trudeau's first house. With only two suitcases and his treasured Mercedes, he took possession when the Pearsons moved to the prime minister's official country retreat at Harrington Lake after the convention.

The two suitcases contained striking and elegant clothing, his wrist bore a gold Rolex, and his thinning hair was artfully shaped to conceal bare skin. "Canadians," the Winnipeg Free Press declared, "are looking to Mr. Trudeau for great things, much in the manner that those Americans who elected John F. Kennedy as their leader expected great things from him." The English-language press abounded with glowing references to Trudeau in the spring of 1968, but the French press, though almost always respectful, was more reserved and even critical. Le Devoir's Claude Ryan had known Trudeau since the 1940s, when he wrote an admiring article for a Catholic journal on the young Quebec intellectual, but he had endorsed Paul Hellyer for the leadership after his first choice, Mitchell Sharp, withdrew in favour of Trudeau. Although he never failed to acknowledge Trudeau's ability and political appeal, he was increasingly critical of his longtime acquaintance's constitutional arguments and especially his arch refusal of special status for Quebec. After dismissing suggestions that Trudeau lacked experience, Ryan said: "But Mr. Trudeau has developed to a very high level some significant qualities. He holds well-articulated personal thoughts. He speaks in the direct terms favoured by today's generation. He appears to fear no person or orthodoxy, whether official or not." While disagreeing with his policies, Ryan acknowledged that there was a clarity to Trudeau's rejection of "special status" for Quebec. Trudeau's position differentiated him not only from Ryan himself but also from Quebec premier Daniel Johnson and Robert Stanfield, who in his first months as Conservative leader began to talk of "two nations"—a concept that was anathema to Trudeau.

Trudeau's rise to national political power was fundamentally a response, first by the Liberal Party and then by many Canadians, to Quebec's new challenge to Canadian confederation. The so-called Quiet Revolution of the early 1960s had shattered the foundations of Quebec's political structures, eroding the Roman Catholic faith that had provided the buttress for tradition. As a vibrant and activist secular state emerged in Quebec, the two political forces of nationalism and separatism exploded and pushed Quebec politicians and intellectuals toward different sides. Once a nationalist and for a brief time a separatist, Trudeau took his stand with those who believed that the future of French-speaking Canadians would be realized most fully within a renewed Canadian federalism. In 1965, as the Pearson-appointed Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism was declaring that Canada was passing through "the greatest crisis" in its history, Trudeau joined with two old friends and collaborators, the journalist Gérard Pelletier and the labour leader Jean Marchand, to become one of "the three wise men" who would sort out the confusion the new Quebec had caused in Ottawa. By 1968 Trudeau had eclipsed his more celebrated colleagues and had become a charismatic leader fit for an extraordinary challenge.

Trudeau had first gained national attention in 1967 with his reforms to the Criminal Code, which he cleverly and memorably described as taking the state out of the bedrooms of the nation. He quickly framed his public character: candid, fresh, and alive with the spirit of the sixties. In a Montreal speech with a strong federalist message that troubled Ryan, Trudeau declared that he would speak "truth" in politics and that "les Canadiens français" must hear the truth. Some of them wanted to hesitate, others to obfuscate, but the choices had finally become clear. On the one hand, there was the view that a modern Quebec was incompatible with a united Canada. According to Trudeau this attitude would lead ineluctably to separatism. On the other hand, there was federalism, accompanied "by a new resolve and new methods, [and] the new resources of modern Quebec." For Trudeau, the choice was obvious. Canadian federalism "represents a more pressing, exciting, and enriching challenge than the rupture of separation because it offers to the Québécois, to the French Canadian, the opportunity, the historic chance to participate in the creation of a great political adventure of the future." And so a great political adventure began.

As the tides of Trudeaumania, or la Trudeaumanie, as Quebec's milder version was termed, swept over the popular media, dissenters began to appear, particularly in his native province. Their ranks included many who had shared earlier adventures with Trudeau. From the left came complaints that the new "pragmatist" had abandoned his own core beliefs in favour of a naked thrust for power. Le Devoir carried a bitter attack from McGill historian, tele vision host, and NDP activist Laurier LaPierre, who denounced Trudeau's constitutional rigidity, his opposition to Quebec nationalism, and his silence over the Vietnam War. LaPierre, later a Liberal senator, said that far from catalyzing change, the election of Trudeau would mean a return to the "do little" politics of Mackenzie King and the end of Canada. Trudeau became a regular target in the many radical journals that promoted the combined separatist and socialist cause. Some of his oldest friends were now among his most virulent critics: the sociologist Marcel Rioux, who had dined regularly with him when, as two lonely young Quebec intellectuals, they worked in Ottawa in the early 1950s; the brilliant Laval academic Fernand Dumont, who had written often for Cité libre when Trudeau was its editor in the 1950s; and the writer Pierre Vadeboncoeur, who had been Trudeau's close friend during childhood and adolescence.

From the right in Quebec and English Canada came rumours of Trudeau's homosexuality and his flirtations with Communism: the proof lay, it was said, in his trips to the Soviet Union and China. Although right-wing columnist Lubor Zink touched on these subjects in the mainstream Toronto Telegram, most Canadian journalists ignored or dismissed the tales as scatological. To his credit, Claude Ryan sternly and admirably rebuked those, including some within the Church, who spread "calomnies insidieuses" about Trudeau. While declaring that he was increasingly opposed to Trudeau's policies, Ryan recalled that the two had shared "une vieille amitié" since the 1940s and that he could personally attest that such attacks had absolutely "no basis in fact."

Some friends had left Trudeau, but he found new allies who, together with Marchand and Pelletier, reassured him that his course was correct. Friends and colleagues mattered a lot to Trudeau, but his first journey after gaining the Liberal leadership was to Montreal to visit his closest confidant—his mother, Grace Elliott Trudeau. Widowed in 1935, she had since devoted herself to her three children and doted especially on Pierre, her elder son, who shared her gracious home in the prosperous Montreal suburb of Outremont until he became prime minister. An easy banter had developed between them in the 1940s as Trudeau formed his adult personality, and in his mother's presence, he retained a wondrous blend of playfulness and serious purpose. They went to the symphony together, cruised the corniches of the Riviera on his Harley-Davidson, and shared the pain when Pierre's romantic life faltered, as it often did in the forties and fifties. Grace could be critical when women did not meet her standards, and most of Pierre's dates recall their trepidation as they mounted the steps at 84 McCulloch Avenue. In the mid-sixties, however, Grace's mind became cloudy. She probably did not know that her son became Canada's prime minister in 1968, although three decades before, she had dreamed that he might. She was, as always, dressed elegantly when he saw her on April 9, and she listened mutely as he held her hand, spoke softly, and told of their most recent and greatest triumph. In silence her strong presence abided.

—

At first Trudeau hesitated to call an election. After the convention he suddenly disappeared, and a frantic press finally discovered him in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with his colleagues Edgar Benson and Jean Marchand and their wives. Benson, a pipe-smoking accountant and early supporter of Trudeau's leadership bid, had co-chaired the Trudeau campaign, although few expected him to have a senior position in the new Cabinet. Marchand also smoked a pipe, but his ebullient nature and fiery oratory, crafted before tough, working-class audiences, contrasted strongly with the phlegmatic Benson's style. Trudeau was comfortable with both, a trait that served him well in politics and in life more generally. By the time he returned to Ottawa and met the Pearson Cabinet on April 17, he was still ambiguous about the election date. He spoke about an "alternative course" in which the House would meet quickly and then dissolve. Two days later the Cabinet's mood was one of "wide disenchantment" with "the present Parliament's effectiveness, and general agreement in the country that the present Parliament was no longer useful or meaningful." Faced with this turnaround, Pearson, who had settled at Harrington Lake with his fishing gear, was obliging when he was asked to resign, and Trudeau swore in his Cabinet on April 20, two days earlier than he had first indicated.

Trudeau had a rich legacy on which to draw: Pearson's Cabinet was one of the most talented in Canadian history, with three future prime ministers in its ranks and several others who would make significant contributions to Canadian public life. Trudeau was cautious in his picks and, as he promised, pragmatic. Prime ministers normally ask their leadership opponents to join the Cabinet, and Trudeau complied. The brilliant and often difficult Eric Kierans was the sole exception—but only because he was not an MP. Joe Greene, whose folksy speech at the convention charmed the delegates and received high marks from the media, became minister of agriculture. John Turner had irritated Trudeau by his decision to remain on the last ballot, but his political talents could not be ignored and he was rewarded with the ministry of consumer and corporate affairs. Paul Hellyer, who had created huge controversy when he unified Canada's armed forces, became minister of transport. The wily and experienced Cape Bretoner Allan MacEachen, who was deeply committed to social Catholicism, became minister of national health and welfare.

The political veteran Paul Martin, who only a year previously had been considered the most likely successor to Pearson, now presented a problem. Trudeau thought poorly of Martin's leadership in the Department of External Affairs, and he blamed some of Martin's people for rumours about his socialism and his personal life. Still, Martin had a following and impressive political experience. The two men met and talked about the justice portfolio, but the devout Catholic Martin did not want to implement the reforms already planned for the Criminal Code, with their liberal approach to homosexuality and abortion. A bit grumpily, the good soldier Martin therefore accepted the position of government leader in the Senate. However, Trudeau's major opponent, Bay Street favourite Robert Winters, decided to step aside after two meetings with Trudeau. "Pierre," Winters said on April 17, "we have been talking for two hours on two successive days, and I still don't know if you want me in your government or if you don't." Trudeau replied, "Well, it's a decision you will have to make." In these laconic words, Trudeau revealed a persistent trait: he insisted that individuals make their own decision. Ardent wooing was not his game.

He had no desire to woo former Pearson minister Judy LaMarsh, who at the convention, with microphone nearby, told Hellyer to fight the "bastard" Trudeau to the end. She resigned abruptly as expected and muttered something about becoming an independent. Trudeau's first Cabinet had no female member, an appalling weakness given that Diefenbaker and Pearson both had female ministers. The influence of francophones and of Quebec was, however, striking. The Cabinet announced on April 20 had eleven ministers from Quebec and eleven francophones. This strong representation appears to have resulted in the assignment of the major offices, External Affairs and Finance, to the Ontarians Mitchell Sharp and Edgar Benson, respectively. The weakness of the Liberal Party in the West limited Trudeau's choices, with British Columbia's Arthur Laing being the only significant western Canadian minister. Charles "Bud" Drury, a superb administrator whose Montreal patrician style appealed to Trudeau, became industry minister, and the effervescent Jean-Luc Pepin, whom Trudeau had known since their university days in Paris in the forties, became minister of labour.

It was, as Trudeau said at the time, a "makeshift" Cabinet designed to emphasize continuity. He also told the press that he chose this particular Cabinet composition to allay any fears that his government "appeared to be that of a new bunch of outsiders coming into the party." Caution and continuity prevailed because an election loomed. Everyone knew the Cabinet that mattered would be formed after the election—a Cabinet that would fully reflect Trudeau's political agenda.

—

Although the Cabinet was traditional, the mood and style in Ottawa were suddenly very different. Reporters were startled and photographers delighted when, on April 22, they spied Trudeau sprinting across Parliament Hill to his office to avoid a group of "girls" from Toronto who were pursuing him. The Globe and Mail featured three photographs of the chase on its front page, following a comment that Trudeau "is clearly savoring his new power and its fringe benefits—old ladies queuing up for his autograph, young girls clamoring to be kissed, mothers holding up their babies to see the great man pass, and traffic jams on the street as motorists stop to catch a glimpse." Cabinet colleagues soon learned, however, that Trudeau's public playfulness and frivolity were left behind at the door. At his first formal meeting, he sternly warned his new ministers that he would not tolerate any "leaks" about his political plans. A leak had apparently occurred the previous weekend, with stories about the "hawks" and the "chickens" in the Cabinet—the former favouring an election, the latter opposing it. He also served notice that he would "ensure improved discipline in the attendance of Ministers in the House of Commons and in the coordination of House business." He established the rudiments of a Cabinet committee system that would become a fundamental alteration in the method of government. From that first meeting, it was apparent that Trudeau meant business. To his political colleagues, he was no longer "Pierre"; he was now "Prime Minister."

The next morning, April 23, he met the caucus on Parliament Hill after a meeting with Senators Dick Stanbury and John Nichol, the present and past Liberal Party presidents, to discuss the latest very good poll results. The caucus was raucous, and most Liberal MPs were ready for an election. So was Trudeau. He went immediately to his West Block office and slipped away via a secret staircase. Then, to avoid suspicion, he entered a car in which a puzzled Paul Martin was waiting. They travelled inconspicuously past the Parliament Buildings and along Rideau Street and soon arrived at Martin's residence at Champlain Towers, in Ottawa's east end. They descended to the basement garage, where yet another car awaited Trudeau. With the press completely tricked, his new driver took him to Rideau Hall, which he entered by the inconspicuous greenhouse entrance; there a bemused Governor General Roland Michener signed the order dissolving the House. As Martin later wrote, the "twist perfectly illustrated Trudeau's liking for the unexpected and his disdain for convention."

Trudeau then returned to the House of Commons and announced that there would be an election on June 25. The twenty-seventh Parliament ended five minutes after it began, with order papers thrown wildly into the air amid yelps of joy and final embraces before the campaign. Stanfield was furious, and he said at his press conference that Trudeau's request for a mandate was absurd, given that there was "no record, no policy, and no proof of his ability to govern the country." But it was not only the opposition parties that were upset. The unexpected dissolution of Parliament left no time for tributes to Lester Pearson—and the revered former prime minister was denied the opportunity to make the gracious speech he had prepared in response to the expected generous praise of his friends, colleagues, and successor. To make matters worse, April 23 was his seventy-first birthday. Maryon Pearson's affection for Trudeau diminished—though not greatly. The slight was not deliberate, but it reflected a carelessness in personal interactions and manners that sometimes marked Trudeau's behaviour.

Few commented on the oversight, however, and Canadians already seemed too eager to shed memories of Pearson and his stumbling government. With excitement rising, the party that had so coyly embraced Trudeau now rushed to follow his colours. Trudeau recalled his Conservative father complaining bitterly in the thirties about the Liberal "campaign machine," but now the gears of that machine began to grind steadily in his support. Financial support, a considerable worry for the party, suddenly appeared as individual donations complemented substantial funds from the corporate world. Throughout the country MPs, senators, candidates, fundraisers, and others rallied behind their irreverent, unpredictable, puzzling, but wildly popular new leader. They knew, after six years of minority governments, that they finally had a winner. Suzette Trudeau Rouleau, who possessed a sister's skepticism, returned from one rally in shock and declared to a friend: "My goodness, Pierre is like a Beatle." There was even a popular song, "PM Pierre," with such lines as "PM Pierre with the ladies, racin' a Mercedes / Pierre, in the money, find him with a bunny."

Aware of the photographer's moment and the quick quip—the "sound bite" that slips neatly into TV news spots—Trudeau, like the Beatles, lived part of his life as a performance. The Canadian communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, then at the height of his international celebrity, was caught up in the campaign. He immediately declared that Trudeau perfectly fitted the sixties with its instant news, colour TV, and politics integrating quickly into the new technologies. "The story of Pierre Trudeau," he wrote, "is the story of the Man in the Mask. That is why he came into his own with TV. His image has been shaped by the Canadian cultural gap. Canada has never had an identity. Instead it has had a cultural interface of 17th-century France and 19th-century America. After World War II, French Canada leapt into the 20th century without ever having had a 19th century. Like all backward and tribal societies, it is very much 'turned on' or at home in the new electric world of the 20th century." Such comments appalled many of McLuhan's academic colleagues, but Trudeau himself was intrigued. He shared McLuhan's intuition that the new media had transformed not only politics but also what a politician represented to the electorate. A correspondence between Trudeau and McLuhan, rich in irony and playfulness, began during the election campaign. When the CBC organized a leaders' debate—the first in Canadian history—McLuhan rightly criticized the format in a letter to Trudeau. "The witness box cum lectern cum pulpit spaces for the candidates was totally non-TV." "Total TV," however, was perfect for Trudeau's cool, detached, but vital image. "The age of tactility via television and radio is one of the innumerable interfaces or 'gaps' that replace the old connections, legal, literate, and visual," he told Trudeau.

—

In terms of the media, the 1968 election represents a historic divide. Seventeen million Canadians watched the Liberal convention, and almost as many watched the leaders' debate. Polling became constant, and American-style tours based on flights that jumped across the country became the norm. Trudeau flew in a DC-9 jet and followed a tight script: a brief statement, passage through the city centre in a convertible, followed by a shopping centre or hockey rink rally with cheerleaders clad in orange and white miniskirts. Cameras, of course, recorded Trudeau's progress. Journalist Walter Stewart, Tommy Douglas's sympathetic biographer, wrote that "beside Trudeau, Stanfield seemed lumpish and Tommy petulant. Stanfield flew in a propeller-driven DC-7 at half Trudeau's speed and made laconic, dull, and sensible speeches. Tommy Douglas flew economy on Air Canada and made provocative speeches that, in most cases, he might as well have shouted into the closet back in his Burnaby apartment." The opposition leaders struggled to find an issue that would focus the campaign, but they were not successful.

Trudeau seemed bemused at the attention he received and remained so when he wrote his memoirs twenty-five years later. He recalled the "exceptional enthusiasm" of the crowds and the astonishing number of people who came to see. In Victoria, "a city of peaceful, respectable folk, many of them retired," he had to be lowered from a helicopter onto a hill, where he was surrounded by thousands. He decided that the crowds came not to hear his speeches but to see the "neo-politician who had made such a splash." It was "part of the spirit of the times," part of the post-Expo mood of "festivity."

There was certainly spontaneous excitement during the campaign, but there was also careful staging as the Liberal strategists focused on their leader in a way that only the new media made possible. For the TV cameras, they even staged a fake fall down the stairs by the athletic Trudeau. They had used "consultants" in 1963 to try to remake Pearson's dowdy presence, but they were much more sophisticated five years later as they copied recent innovations in American politics. Richard Nixon loathed television, but he had learned from his ill-fated 1960 debate with John F. Kennedy, when he won among radio listeners but lost badly among those who watched his dark shadows on the screen, that politics had become principally the manipulation of images. Television embraced Trudeau: the dramatic high cheekbones; the intense blue eyes; the quick change of moods from caustic to shy to affectionate; the striking retort; and the "cool" presence. Somehow the camera missed his pock-marked cheeks, the faintly yellow tinge to his complexion, and his less than average height. A grudging Walter Stewart complained that "whatever quality it is that [makes] TV work for one person and not for another, Trudeau had it."

A superb actor, Trudeau knew well what the crowd wanted: the expert jackknife into a pool, beautiful and brilliant young people, and stunning women in miniskirts surrounding him. In his memoirs, he tellingly chose a photograph of a buxom young woman wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with "Vote P.E.T. or Bust." George Bain, the Globe and Mail's senior columnist, wrote caustically of the Trudeau campaign: "If it puckers, he's there." And, seemingly, he always was.

Trudeau enjoyed the attention, but he strongly resisted its tendency to trivialize his political message. Perhaps in response to Bain's effective jibe, Trudeau gave him a long interview in which he tried to elaborate on the Liberals' platform and, in particular, his call for a "Just Society." At the time, May 22, the English press was becoming critical of the emphasis on style over substance in the Trudeau campaign. When Bain demanded, "What is a just society?" Trudeau replied:

It means certain things in a legal sense—freeing an individual so he will be rid of his shackles and permitted to fulfil himself in society in the way which he judges best, without being bound up by standards of morality which have nothing to do with law and order but which have to do with prejudice and religious superstition.

Another aspect of it is economic, and, rather than develop that in terms of social legislation and welfare benefits, which I do not reject or condemn, I feel that at this time it is more important to develop in terms of groups of people . . . The Just Society means not giving them a bit more money or a bit more welfare. The Just Society for them means permitting the province or the region as a whole to have a developing economy. In other words, not to try to help merely the individuals but to try to help the region itself to make all parts of Canada liveable in an acceptable sense . . .

Another one, I think, is in terms of our relations with other countries. . . . Canada [is] . . . a country of modest proportions in world terms—not geographically, but economically and in terms of its population—we must make sure that our contribution to world order is . . . not only . . . to appear just [but] . . . to be just.

The outlines of the "Just Society" remain faintly drawn in this interview, but the absence of sharp detail was intentional. Trudeau worried about expectations, and he took refuge in ambiguity and caution. He signalled that the great innovations in social welfare of the Pearson years—the Canada Pension Plan, medicare, and Canada Student Loans—would have no immediate successors. He would focus on "groups"; regions; and broad, incremental change. This comment took tangible form in the Trudeau years in new programs for regional economic development, special grants for youth and Aboriginals, recognition of the language rights of francophones throughout Canada, and the establishment of avenues through which francophones could more easily reach the pinnacle of the public service in Canada.

Despite the apparent modesty of the proposed programs, Trudeau believed that he represented a revolutionary innovation in Canadian politics. He urged Canadians to "take a chance" on him, even though he was unwilling to tell them yet what their wager would mean. He played with their hopes, artfully revealing little while raising expectations. He had rehearsed for this moment since adolescence. On New Year's Day 1938, he had written in his diary: "If you want to know my thoughts, read between the lines," and six months later, he was forthright in expressing his ambitions: "I would like so much to be a great politician and to guide my nation." He knew that ambiguity, paradox, irony, and a seductive elusiveness were assets in achieving the goal he had so long cherished: to be a great politician guiding a nation and affecting destiny. Pierre Trudeau had never been as happy as he was in the spring of 1968, and he revelled in the first sips of power.

He loved the highest office, though he was wary, even fearful, of its personal costs and the flamboyant manner he had used to achieve it. He cherished his privacy, shunned close emotional attachment, and often took moments where no one could pierce his silence. Those around him quickly learned to retreat at those times. The campaign, moreover, was a long one, and the constant repetition of airport greetings, motorcades, and rallies began to bore him. He worried whether his legitimacy as an intellectual who had helped to shape his province in the postwar years might not be undermined by the trivialities of the campaign. He was especially annoyed in parts of Quebec when his sexual orientation was questioned. The Créditiste strength in rural Quebec drew on profound doubts about the Quiet Revolution—doubts that had led to defeat for the Lesage government in 1966 and, in 1968, threatened the federal Liberal appeal in those areas. The rumours about Trudeau's "Communism" and sexual tastes were so strong that he was forced to confront them directly in rallies in the Lac St-Jean region.

In English Canada and urban Quebec, the personal issues were ignored in the mainstream press. There was, as usual, a striking difference between the campaigns in French and English Canada, in terms of issues and reporting. A major cause of this situation dated back to the previous year, when the Johnson government in Quebec decided to build on France's willingness to give the province international stature by accepting invitations to international conferences. This had struck Trudeau and others as a dramatic and dangerous threat to Canadian federalism. Then, in mid-1967 French president Charles de Gaulle proclaimed, "Vive le Québec libre!" before a cheering crowd at Montreal's Hôtel de Ville, stunning Canadians who were joyously celebrating their Centennial and catalyzing the swelling forces of separatism in the province of Quebec. Paul Martin in External Affairs worried that a firm rebuke would accomplish little. There was, he reported to Cabinet, "no mistaking the enthusiasm for de Gaulle in Montreal and at Expo 67." Trudeau, who had spoken seldom in Cabinet since his appointment in April, quickly dismissed these concerns. "The people in France," he warned, "would think the Government was weak if it did not react; the General had not the support of the intellectuals in his country and the French press was opposed to him." An angry Pearson backed Trudeau and rebuked de Gaulle, who immediately flew home to Paris. In this incident, Trudeau had made a strong impression on Pearson, the Cabinet, and even General de Gaulle—who concluded that Trudeau was "the enemy of the French fact in Canada."

Now, Trudeau deliberately made Quebec's international ambitions a campaign issue—indeed, Cabinet records reveal that they were the principal reason he decided to call an early election. Moreover, the Quebec NDP and Conservative leaders, Robert Cliche and Marcel Faribault, respectively, both supported the idea of "deux nations" or "statut particulier" (two nations or special status) for Quebec—a position Trudeau had not only long opposed but regarded as the slippery slope heading directly to separatism. These various ambitions gave Trudeau his "issue." His Quebec speeches were more formal, with much more content and less political fluff than his speeches in the rest of Canada. In response, the Quebec press took what he said more seriously and, except in the tabloids, completely ignored the "puckering."

Trudeau also faced greater controversy and more strident and even vocal opposition in Quebec. The June 1 death of André Laurendeau, the co-chair of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, shocked Trudeau, and he wept openly at the June 4 funeral in Outremont. Laurendeau had been an early mentor, a frequent critic, and a shrewd observer of Trudeau's career. Together, Trudeau, Marchand, and Pelletier attended the funeral at Église Saint-Viateur, a church where Trudeau frequently prayed. As they left the church, a crowd confronted them, its leaders shouting, "Traitors! Goddamn traitors! Go back to Ottawa." The event jarred Trudeau. He became less comfortable with the campaign's demands on him and less willing to "pucker and run" during carefully staged events and scripted speeches. The following day, Trudeau was scheduled to give a speech in Sudbury on "Northern Problems and the Just Society," which even its author, Ramsay Cook, regarded as uninspiring. He threw away the speech and "passionately improvised before a large attentive audience." He spoke with feeling of Laurendeau and of his own commitment to tolerance and diversity. He angrily attacked those who had killed Bobby Kennedy earlier that day and linked them with the terrorists in Quebec. Pearson phoned Marc Lalonde, his former assistant, who had urged Trudeau to enter politics, to tell him it was the best political speech he had ever heard. When Cook offered his own praise, Trudeau responded by "smiling wickedly" and saying, "And you didn't write it!"

Trudeau increasingly resisted his advisers as the campaign progressed, and the adoring crowds in parts of English Canada caused him to ease his normal discipline. At a meeting for a new "star candidate" in the constituency of North York, Trudeau introduced Barney Danson as Barney Dawson. Danson corrected him, but minutes later Trudeau called him "Barry Danson." The errors did not matter: two days before the election, Danson's Conservative opponent informed him that he had given up: "This Trudeau thing is just too big." Trudeau's national opponents were similarly frustrated. His debate performance on June 9 was flat, and he seems unfairly to have blamed those who prepared him. He had followed the script, while Tommy Douglas and Créditiste leader Réal Caouette were humorous and spontaneous. Former Liberal Party president John Nichol recalls how, as the campaign progressed, Trudeau increasingly refused to go beyond the prearranged schedule and argued with campaign manager Bill Lee about every new demand. As Edith Iglauer, the New Yorker journalist, observed while travelling with Trudeau, the new prime minister, unlike Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and most other politicians, insisted on at least eight hours' sleep at night.

This regimen made campaigning difficult in a country that covers several time zones. On June 15 Nichol and other advisers had a bitter exchange with Trudeau when he refused to make one last western trip. A furious Nichol hollered that "hundreds of Liberals—candidates and their workers—had been working for weeks preparing for him to come." When he threatened to resign, Trudeau reluctantly gave in. With success and celebrity, the campaign had become bloated with assistants, advisers, and "hangers on." Richard Stanbury, who had replaced Nichol as Liberal Party president, wrote in his diary that Trudeau's popularity had attracted too many admirers eager to be near the coming Messiah. He even intervened himself to keep some Trudeau enthusiasts, including an exuberant Michael Ignatieff, at a greater distance from the leader.

Whatever the campaign's flaws, the roar of the crowds and the excitement around the leader smothered any doubters among Liberals. Unlike the Conservatives, where sparring between former leader John Diefenbaker and Robert Stanfield marred the campaign, the Liberals seemed united, and no more so than on June 19 in Toronto. Over fifty thousand gathered on Nathan Phillips Square at noon to cheer Trudeau. Later in the day, he went to the riding of York Centre, where Lester Pearson introduced him with glowing words: "A man prepared to speak out loud and clear in favour of unity . . . A man who doesn't make idle promises . . . A man for today and a man for tomorrow . . . My friend, my former colleague, a man for all Canada—Pierre Elliott Trudeau." As the Liberal leader came forward, Pearson beamed at his successor and tears welled up in Trudeau's eyes.

Perhaps because his welcome was so warm in English Canada, the increasingly hostile press coverage in Quebec angered Trudeau—and his combative instincts led him to respond more aggressively than his advisers thought wise. He would privately attack journalists as ignorant and boring, the news media as "the last tyranny" in free societies. He engaged in an unseemly quarrel over whether Conservative star candidate Marcel Faribault had been personally involved in banning him from teaching at the Université de Montréal in the early fifties on the grounds that he was a socialist. Claude Ryan became more caustic as the campaign neared its end, and even the Montreal Gazette waxed critical. It was no surprise, then, when the Gazette, which had supported the Liberals in 1965, urged its readers to vote for "an enlightened Conservatism" that "does not attempt to dazzle without reason; or lead without explanation; act without steadiness; or discard without cause; or add without need."

Stanfield's campaign had impressed many editorialists, especially in Quebec, where Le Devoir, L'Action, and the Sherbrooke Record all endorsed the Conservatives, and even the traditionally Liberal La Presse, Le Droit, and Le Soleil attached reservations to their support of Trudeau. In rural Quebec, Caouette campaigned relentlessly and successfully against Trudeau's liberal social programs and "socialist" economics, while rumours about Trudeau's sexual orientation continued to animate discussions at the rural boucheries and dépanneurs. In Montreal, Pierre Bourgault of the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN) attacked Trudeau unrelentingly as a vendu and warned him not to attend the historic parade on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Not surprisingly, Trudeau announced he would be there. He argued with close advisers and Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau, who told him that violence was certain if he went. When Richard Stanbury accompanied him to his house before the rally, a roughly dressed man who obviously knew Trudeau stopped him and warned him to stay at home. Trudeau told Stanbury that the man was a friend from his youth who was now close to violent separatists. Trudeau thanked his old chum but ignored his advice.

As darkness fell on June 24, election eve, Trudeau arrived at the reviewing stand on Sherbrooke Street for the parade. He took his place between Archbishop of Montreal Paul Grégoire and Premier Daniel Johnson, two seats away from Mayor Drapeau. Despite the hundreds of police milling about, the crowd broke into chants of "Tru-deau au pot-eau" (Trudeau to the gallows), and suddenly, the hostile throng erupted into a violent riot, throwing bottles and stones. Sirens blared, ambulances and police cars sped in and out. Defiant, Trudeau stood up and waved, but the chants intensified. One police car was overturned; another was aflame. Demonstrators poured out of Lafontaine Park onto the streets, which by this time were sprinkled with shattered glass. Suddenly, a bottle came through the air toward the reviewing stand. Seeing its arc, Drapeau fled with his wife, Johnson escaped, and two RCMP officers moved quickly to shield the prime minister. One threw his raincoat over him, but Trudeau flung it aside, put his elbows on the railing, and stared defiantly at the melee below. He stood there alone, his visage stony. The crowd, initially stunned, began slowly to applaud Trudeau's courage. The Mounties, realizing that he would not be moved, sat down beside him as he stayed to the parade's end at 11:20 p.m. The startling images of Trudeau confronting the rioters dominated the late television news throughout Canada. The following morning, the front pages of the newspapers featured photographs of Trudeau's icy defiance on the reviewing stand, while editorialists paid tribute to his character and strength. The whole performance embellished Trudeau's steely image and confirmed the impression that here was a leader. And, in truth, it was election day.

Trudeau voted in an overcast Montreal that morning and then flew to Ottawa. There he visited Liberal headquarters and thanked the party workers before having dinner at his new home on Sussex Drive. After the polls closed, his driver took him to the historic Château Laurier hotel, where police held back the crowd as he made his way to the Liberal suites on the fifth floor. Campaign workers gathered below. Trudeau watched the returns and worked on his speech in a small bedroom at one end of the floor. He emerged briefly to greet Lester and Maryon Pearson, whom he hadinvited to join him. The night began badly with the loss of 6 Liberal seats in Newfoundland, followed by a Conservative sweep of Prince Edward Island's 4 seats and 10 of the 11 Nova Scotia seats—a testimony to the personal appeal of Bob Stanfield. Then the Conservative tide slowed dramatically as it reached the franco phone constituencies of New Brunswick and collapsed in Quebec, where the Liberals took 53.3 percent of the vote and 56 of its 74 seats. Trudeaumania held in Ontario, where the Liberals took 64 of its 88 seats. When the night ended, the victory was decisive. Even Alberta, which had rejected the Liberal Party for over a generation, gave 4 seats to Trudeau. In British Columbia, Tommy Douglas lost his own seat as the Liberals won 16 in all—9 more than in 1965.

A later academic study of the election is especially revealing. The Liberals took 45.2 percent of the popular vote but 63.9 percent of "professionals," 72.2 percent of immigrants after 1946, 67.1 percent of francophones, and 59.2 percent of Canadians under the age of thirty. Large metropolitan areas gave 67.7 percent of their votes to the Liberals. The Conservatives led slightly among rural Canadians, and the populist and rural Ralliement des Créditistes raised their party standing from 8 at dissolution to 14. However, bad economic conditions probably mattered more to Créditiste voters than the rumours about Trudeau's radical ways and sexual habits. As Claude Ryan grudgingly admitted, most francophones reached the same conclusion they had earlier with Wilfrid Laurier and Louis St. Laurent: "After all, here's a French Canadian who has become prime minister. Why not give him a fair chance?"

Given the chance, Trudeau was exultant. He waited for Stanfield to concede, which he did with his usual grace. Unfortunately, John Diefenbaker chose to make a national address as well, where he declared the result a "calamitous disaster for the Conservative Party" and seemed to relish the deluge that had come after him. Trudeau ignored Diefenbaker's remarks and praised both Stanfield and Douglas. Then he declared: "For me it was a great discovery. . . . We now know more about this country, which we did not know two months ago. . . . The election has been fought in a mood of optimism and confidence in our future. . . . We must intensify the opportunities for learning about each other." He was unexpectedly solemn but clearly pleased. He knew his time had come.

But what exactly did "we" know? What had Canadians learned about themselves and their new prime minister? Trudeau's personal appeal to the young and the francophones was obvious. Interestingly, he increased Liberal support among men (from 39 percent in 1965 to 45 percent in 1968) more than among women (from 43 percent to 48 percent). As with John Kennedy, men apparently admired both Trudeau's manly courage and his sex appeal to women. Whatever the psychological causes, both opponents and supporters gave Trudeau credit for the victory; Stanfield and Douglas later said that the die was cast against them when Pearson resigned and Winters' campaign failed. Nevertheless, John Duffy, in his history of Canada's decisive elections, omits 1968 because, he argues, the election confirmed existing trends and created no dramatic rupture from the past.

Trudeau himself minimized the extent of change that his government represented. His outline of the Just Society was faint in detail yet familiar in its references. He was, in his own words, a "pragmatist" among Canadians, who were "accustomed to deal with their problems in a pragmatic way." The erstwhile socialist and adolescent revolutionary bluntly rebuked an Ontario crowd: "You know that no government is a Santa Claus, and I thought as I came down the street and saw all the waves and the handshakes that I'd remind you that Ottawa is not a Santa Claus." There would be no great programs, his government would not raise taxes, and he would make no rash promises.

Duffy is correct to suggest continuity and to point out how the foundations of Canadian electoral behaviour persisted in 1968. The Liberals were becoming ever more the urban, immigrant, and francophone party throughout the 1960s, while the Conservatives became more rural and anglophone. Unlike the historic elections of 1896, 1925ߝ26, and 1957ߝ58, no fundamental realignment and no great dividing issues characterized the election of 1968. Indeed, journalists struggled to find issues that separated the parties, especially in English Canada. In another sense, however, both Duffy and Trudeau misled by minimizing the change that Trudeau represented. Stanfield, Winters, or Hellyer would have been very different prime ministers, and if elected, any of them would have produced a very different Canada.

The significance of the 1968 election derives partly from Trudeau's unique personality, but the major distinction comes from the particular moment when the election occurred and the manner in which Trudeau reflected it: the spring of 1968. The images endure: Paris aflame; the Tet offensive in Vietnam; Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King gunned down; police clubbing Harvard students; the Beatles and the Stones; and the liberation of the Prague Spring. Into this collage, Trudeau, defiant on the platform and elegant on the diving board, fits perfectly. Pierre Trudeau's style mimicked the times—and forecast a new Canada.

From the Hardcover edition.

TAKING POWER

The champagne sparkled, the boyish smile lingered as Pierre Elliott Trudeau waved to the cheering crowd at the Liberal convention in 1968. On April 6, a Saturday afternoon, the forty-eight-year-old Montrealer and Canada's reformist minister of justice was elected on the fourth ballot as the seventh Liberal leader since Confederation. His victory meant that he would become the sixth Liberal prime minister of Canada. Donning the mantle of Laurier and King, St. Laurent and Pearson, Trudeau prepared to address not only the delegates at Ottawa's Civic Centre but also the curious nation beyond, which, gathered around mostly black-and-white television sets, was about to witness the birth of "Trudeaumania." Whatever the meaning of the phenomenon, the evening seemed historic, for Trudeau would be the first Canadian prime minister born in the twentieth century, the youngest prime minister since the 1920s, and with fewer than three years in the House of Commons, the least experienced prime minister in Canada's history.

The Trudeau crowd was young but so were the times. Trudeau had begun his victorious campaign to capture the Prime Minister's Office just as the Beatles launched their Magical Mystery Tour and the musical Hair declared its discovery of sex, drugs, and rock and roll and headed for Broadway. The year blended magic and political shock as the fringe and the alternative merged with the mainstream. At the end of January, the Viet Cong had stunned American forces in Vietnam with its Tet offensive, and the American presidency of Lyndon Johnson suddenly began to crumble. Richard Nixon, the old Cold Warrior, returned from the political wilderness to become a serious Republican contender for the presidency as Democrats jostled to succeed Johnson. And the American dream had become a nightmare. That vision of promise, embodied in the young and eloquent John F. Kennedy, had entranced Canadians at the beginning of the decade, but Kennedy was gone, and on Thursday, April 4, the day before the Liberal leadership convention began, James Earl Ray had gunned down the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., as the civil rights leader stood on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee. The eruption of violence in America's largest cities following King's assassination shared front-page headlines in Canada's newspapers with the convention triumph of Pierre Trudeau.

The contrast was striking. Canada suddenly seemed different (cool in the argot of the day), a "peaceable kingdom" as some now called it. In this setting the candidacy of the parliamentarian of only three years became politically intriguing. His style and stance were unique in the history of Canada: an erstwhile socialist who cared what French intellectuals wrote, wore shoes without socks and jackets without ties and still looked elegant, drove the perfect Mercedes 300SL convertible, and flirted boldly with women a generation younger. That April weekend the American counterparts of the youth at the Ottawa Civic Centre were angrily demonstrating in the streets or on campuses. Bob Rae, then a hairy, rumpled student radical at the University of Toronto, later recalled how he went off to that convention, drawn to Trudeau's incisiveness, wit, "belief that ideas mattered in politics," and most of all, his "style." His roommate and fellow student activist, Michael Ignatieff, joined the Trudeau team and claimed, forty years later, that politics were never again as exciting for him as during those heady days in the spring of 1968. John Turner supporter Bruce Allen Powe took his thirteen-year-old son to the convention, where Bruce Jr. defied his father's allegiance, hid his Trudeau buttons beneath his jacket, and began a lifelong infatuation.

The infatuation was infectious. After the convention formally ended, Trudeau's supporters and thousands of others crammed into the new Skyline Hotel in downtown Ottawa, where the "curvaceous" Diamond Lil performed one of her livelier dances between two Trudeau campaign posters. Throngs of miniskirted teenagers screamed a welcome to the new leader, and older followers sang "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow." "Let's party tonight," a beaming Trudeau told the crowd, "but remember that Monday the party is over."

Before long, Trudeau spotted Bob Rae's striking young sister, Jennifer, across the room, and fastening his penetrating blue eyes on her, he came close and whispered, "Will you go out with me sometime?" She later did, but he also remembered the fetching teenager who had spurned him in Tahiti the previous December but had willingly accepted his eager kiss that afternoon as he left the convention floor. When reporters asked Margaret Sinclair, the daughter of a former Liberal Cabinet minister, "Have you eyes for Trudeau? Are you a girlfriend?" she replied, "No, I have eyes for him only as prime minister." The office had already brought Trudeau unanticipated benefits, and for the first time since Laurier, a Canadian prime minister was sexy.

Trudeau knew that public expectations were too high, and he moved quickly to dampen them in his acceptance speech at the convention and at his next appearance. The acceptance speech reads poorly, but content mattered little, as Trudeau's words were submerged in the froth of victory. On April 7, the day after he became leader, Trudeau held a nationally televised press conference. Sporting the fresh red rose that had already become his trademark, he praised his opponents—particularly Robert Winters, who had finished second—and said he was considering how they would fit into his Cabinet. To the surprise of some commentators, he indicated there was no need for an immediate election. Then, unexpectedly, he denied that he was a radical or a "man of the left." "I am," he declared, "essentially a pragmatist." The comment confused many observers.

Not long before, Trudeau had proudly declared himself a leftist. Evidence of his "radicalism" and left-wing views abounded in old newspaper clippings; in the memories of many who knew him; and in Cité libre, the journal he had edited in the 1950s. New Democratic Party leader Tommy Douglas recalled trying to recruit Trudeau as a socialist candidate only a few years earlier. Trudeau knew that his future success rested on reassurance, which paradoxically required ambiguity, rather than strong assertions of principle. At the convention he'd talked about the "Just Society" he intended to construct, but its contours were thinly sketched and its foundations, apart from a commitment to the rights of individuals to make their own decisions, were barely visible.

Ambiguity or, perhaps more accurately, mystery was apparently alluring. Even the Spectator, the British conservative magazine so often given to cynical observations about the oldest dominion, succumbed to the enthusiasm surrounding Trudeau: "It was as if Canada had come of age, as if he himself single handedly would catapult the country into the brilliant sunshine of the late 20th century from the stagnant swamp of traditionalism and mediocrity in which Canadian politics had been bogged down for years." In the spring of 1968, an intrigued William Shawn, the celebrated editor of the New Yorker, commissioned Edith Iglauer to write a long article on Canada's new prime minister. It took a year to complete, but it remains the best portrait of Trudeau as he took power and shaped his private self to the new demands of public life.

Leading Canadian journalists could not resist his charm, and many cast objectivity to the winds and signed a petition endorsing Trudeau. Historian Ramsay Cook, a traditional supporter of the New Democratic Party but a Trudeau speechwriter in 1968, retains a scrap of paper from that year which reads: "Pierre Trudeau is a good shit (merde)." It was signed by eminent leftist journalist June Callwood and her sportswriter husband, Trent Frayne; Maclean's editor Peter Gzowski and his wife, Jenny; and the brash young interviewer Barbara Frum. Peter C. Newman, the talented and bestselling political journalist at the Toronto Star, commented, "The whole house of clichés constructed by generations of politicians is demolished as soon as [Trudeau] begins to speak."

—

Trudeau's freshness seemed to free him from the dense political foliage and sombre shades that had darkened Ottawa in the mid-1960s, when Canada, in Newman's famous term, suffered from political "distemper." Two veterans of the First World War, John Diefenbaker and Lester Pearson, fought pitched battles that both bored and infuriated Canadians. The Conservatives rejected Diefenbaker in a bitter convention in 1967 and turned to the Nova Scotia premier, Robert Stanfield, whose laconic style and careful ways contrasted strongly with the fiery Saskatchewan populist. The seventy-year-old Pearson stepped aside more gracefully just before Christmas 1967, when the polls were showing that Stanfield would trounce the Liberals should the government fall. The Liberal minority tottered as the candidates for Pearson's succession took their places in the winter of 1968. By that time Pearson had become convinced that his successor should be Pierre Trudeau, who had been his parliamentary secretary but had remained personally distant. Pearson told a close friend that "ice water" ran through Trudeau's veins. Still, his successor had to be a francophone, he thought, and Trudeau's intellect, his presence, and even his cold rationality made him the logical choice. Pearson's wife, Maryon, was openly smitten with the charm Trudeau so deftly and consciously revealed to women, and her affection for her husband's successor was obvious to all. A cartoonist wrote a caption on a photograph above Maryon as she gazed fondly at Trudeau: "Of course, Pierre, you realize that if you win, I go with the job." She didn't, but the Victorian mansion on Sussex Drive did. It was the bachelor Pierre Trudeau's first house. With only two suitcases and his treasured Mercedes, he took possession when the Pearsons moved to the prime minister's official country retreat at Harrington Lake after the convention.

The two suitcases contained striking and elegant clothing, his wrist bore a gold Rolex, and his thinning hair was artfully shaped to conceal bare skin. "Canadians," the Winnipeg Free Press declared, "are looking to Mr. Trudeau for great things, much in the manner that those Americans who elected John F. Kennedy as their leader expected great things from him." The English-language press abounded with glowing references to Trudeau in the spring of 1968, but the French press, though almost always respectful, was more reserved and even critical. Le Devoir's Claude Ryan had known Trudeau since the 1940s, when he wrote an admiring article for a Catholic journal on the young Quebec intellectual, but he had endorsed Paul Hellyer for the leadership after his first choice, Mitchell Sharp, withdrew in favour of Trudeau. Although he never failed to acknowledge Trudeau's ability and political appeal, he was increasingly critical of his longtime acquaintance's constitutional arguments and especially his arch refusal of special status for Quebec. After dismissing suggestions that Trudeau lacked experience, Ryan said: "But Mr. Trudeau has developed to a very high level some significant qualities. He holds well-articulated personal thoughts. He speaks in the direct terms favoured by today's generation. He appears to fear no person or orthodoxy, whether official or not." While disagreeing with his policies, Ryan acknowledged that there was a clarity to Trudeau's rejection of "special status" for Quebec. Trudeau's position differentiated him not only from Ryan himself but also from Quebec premier Daniel Johnson and Robert Stanfield, who in his first months as Conservative leader began to talk of "two nations"—a concept that was anathema to Trudeau.

Trudeau's rise to national political power was fundamentally a response, first by the Liberal Party and then by many Canadians, to Quebec's new challenge to Canadian confederation. The so-called Quiet Revolution of the early 1960s had shattered the foundations of Quebec's political structures, eroding the Roman Catholic faith that had provided the buttress for tradition. As a vibrant and activist secular state emerged in Quebec, the two political forces of nationalism and separatism exploded and pushed Quebec politicians and intellectuals toward different sides. Once a nationalist and for a brief time a separatist, Trudeau took his stand with those who believed that the future of French-speaking Canadians would be realized most fully within a renewed Canadian federalism. In 1965, as the Pearson-appointed Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism was declaring that Canada was passing through "the greatest crisis" in its history, Trudeau joined with two old friends and collaborators, the journalist Gérard Pelletier and the labour leader Jean Marchand, to become one of "the three wise men" who would sort out the confusion the new Quebec had caused in Ottawa. By 1968 Trudeau had eclipsed his more celebrated colleagues and had become a charismatic leader fit for an extraordinary challenge.

Trudeau had first gained national attention in 1967 with his reforms to the Criminal Code, which he cleverly and memorably described as taking the state out of the bedrooms of the nation. He quickly framed his public character: candid, fresh, and alive with the spirit of the sixties. In a Montreal speech with a strong federalist message that troubled Ryan, Trudeau declared that he would speak "truth" in politics and that "les Canadiens français" must hear the truth. Some of them wanted to hesitate, others to obfuscate, but the choices had finally become clear. On the one hand, there was the view that a modern Quebec was incompatible with a united Canada. According to Trudeau this attitude would lead ineluctably to separatism. On the other hand, there was federalism, accompanied "by a new resolve and new methods, [and] the new resources of modern Quebec." For Trudeau, the choice was obvious. Canadian federalism "represents a more pressing, exciting, and enriching challenge than the rupture of separation because it offers to the Québécois, to the French Canadian, the opportunity, the historic chance to participate in the creation of a great political adventure of the future." And so a great political adventure began.

As the tides of Trudeaumania, or la Trudeaumanie, as Quebec's milder version was termed, swept over the popular media, dissenters began to appear, particularly in his native province. Their ranks included many who had shared earlier adventures with Trudeau. From the left came complaints that the new "pragmatist" had abandoned his own core beliefs in favour of a naked thrust for power. Le Devoir carried a bitter attack from McGill historian, tele vision host, and NDP activist Laurier LaPierre, who denounced Trudeau's constitutional rigidity, his opposition to Quebec nationalism, and his silence over the Vietnam War. LaPierre, later a Liberal senator, said that far from catalyzing change, the election of Trudeau would mean a return to the "do little" politics of Mackenzie King and the end of Canada. Trudeau became a regular target in the many radical journals that promoted the combined separatist and socialist cause. Some of his oldest friends were now among his most virulent critics: the sociologist Marcel Rioux, who had dined regularly with him when, as two lonely young Quebec intellectuals, they worked in Ottawa in the early 1950s; the brilliant Laval academic Fernand Dumont, who had written often for Cité libre when Trudeau was its editor in the 1950s; and the writer Pierre Vadeboncoeur, who had been Trudeau's close friend during childhood and adolescence.

From the right in Quebec and English Canada came rumours of Trudeau's homosexuality and his flirtations with Communism: the proof lay, it was said, in his trips to the Soviet Union and China. Although right-wing columnist Lubor Zink touched on these subjects in the mainstream Toronto Telegram, most Canadian journalists ignored or dismissed the tales as scatological. To his credit, Claude Ryan sternly and admirably rebuked those, including some within the Church, who spread "calomnies insidieuses" about Trudeau. While declaring that he was increasingly opposed to Trudeau's policies, Ryan recalled that the two had shared "une vieille amitié" since the 1940s and that he could personally attest that such attacks had absolutely "no basis in fact."

Some friends had left Trudeau, but he found new allies who, together with Marchand and Pelletier, reassured him that his course was correct. Friends and colleagues mattered a lot to Trudeau, but his first journey after gaining the Liberal leadership was to Montreal to visit his closest confidant—his mother, Grace Elliott Trudeau. Widowed in 1935, she had since devoted herself to her three children and doted especially on Pierre, her elder son, who shared her gracious home in the prosperous Montreal suburb of Outremont until he became prime minister. An easy banter had developed between them in the 1940s as Trudeau formed his adult personality, and in his mother's presence, he retained a wondrous blend of playfulness and serious purpose. They went to the symphony together, cruised the corniches of the Riviera on his Harley-Davidson, and shared the pain when Pierre's romantic life faltered, as it often did in the forties and fifties. Grace could be critical when women did not meet her standards, and most of Pierre's dates recall their trepidation as they mounted the steps at 84 McCulloch Avenue. In the mid-sixties, however, Grace's mind became cloudy. She probably did not know that her son became Canada's prime minister in 1968, although three decades before, she had dreamed that he might. She was, as always, dressed elegantly when he saw her on April 9, and she listened mutely as he held her hand, spoke softly, and told of their most recent and greatest triumph. In silence her strong presence abided.

—

At first Trudeau hesitated to call an election. After the convention he suddenly disappeared, and a frantic press finally discovered him in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with his colleagues Edgar Benson and Jean Marchand and their wives. Benson, a pipe-smoking accountant and early supporter of Trudeau's leadership bid, had co-chaired the Trudeau campaign, although few expected him to have a senior position in the new Cabinet. Marchand also smoked a pipe, but his ebullient nature and fiery oratory, crafted before tough, working-class audiences, contrasted strongly with the phlegmatic Benson's style. Trudeau was comfortable with both, a trait that served him well in politics and in life more generally. By the time he returned to Ottawa and met the Pearson Cabinet on April 17, he was still ambiguous about the election date. He spoke about an "alternative course" in which the House would meet quickly and then dissolve. Two days later the Cabinet's mood was one of "wide disenchantment" with "the present Parliament's effectiveness, and general agreement in the country that the present Parliament was no longer useful or meaningful." Faced with this turnaround, Pearson, who had settled at Harrington Lake with his fishing gear, was obliging when he was asked to resign, and Trudeau swore in his Cabinet on April 20, two days earlier than he had first indicated.

Trudeau had a rich legacy on which to draw: Pearson's Cabinet was one of the most talented in Canadian history, with three future prime ministers in its ranks and several others who would make significant contributions to Canadian public life. Trudeau was cautious in his picks and, as he promised, pragmatic. Prime ministers normally ask their leadership opponents to join the Cabinet, and Trudeau complied. The brilliant and often difficult Eric Kierans was the sole exception—but only because he was not an MP. Joe Greene, whose folksy speech at the convention charmed the delegates and received high marks from the media, became minister of agriculture. John Turner had irritated Trudeau by his decision to remain on the last ballot, but his political talents could not be ignored and he was rewarded with the ministry of consumer and corporate affairs. Paul Hellyer, who had created huge controversy when he unified Canada's armed forces, became minister of transport. The wily and experienced Cape Bretoner Allan MacEachen, who was deeply committed to social Catholicism, became minister of national health and welfare.

The political veteran Paul Martin, who only a year previously had been considered the most likely successor to Pearson, now presented a problem. Trudeau thought poorly of Martin's leadership in the Department of External Affairs, and he blamed some of Martin's people for rumours about his socialism and his personal life. Still, Martin had a following and impressive political experience. The two men met and talked about the justice portfolio, but the devout Catholic Martin did not want to implement the reforms already planned for the Criminal Code, with their liberal approach to homosexuality and abortion. A bit grumpily, the good soldier Martin therefore accepted the position of government leader in the Senate. However, Trudeau's major opponent, Bay Street favourite Robert Winters, decided to step aside after two meetings with Trudeau. "Pierre," Winters said on April 17, "we have been talking for two hours on two successive days, and I still don't know if you want me in your government or if you don't." Trudeau replied, "Well, it's a decision you will have to make." In these laconic words, Trudeau revealed a persistent trait: he insisted that individuals make their own decision. Ardent wooing was not his game.