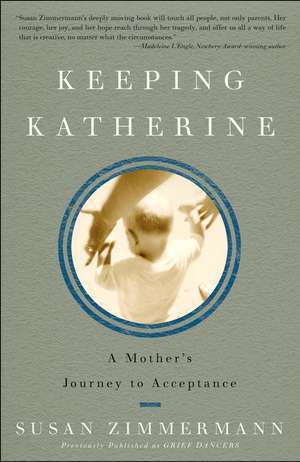

Keeping Katherine: A Mother's Journey to Acceptance

Autor Susan Zimmermannen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2004

In Keeping Katherine, Susan Zimmermann tells the story of her life with her daughter Katherine, who has Rett syndrome, a devastating neurological disorder. Writing with honesty and candor, Zimmermann chronicles her personal journey to accept the changed dynamic of her family; the strain of caring for a special needs child and the pressure it placed on her marriage, career, and relationship with her parents; the dilemma of whether Kat would be better cared for in a group home; and most important, the altered reality of her daughter’s future. A story of personal transformation that reminds us that it isn’t what happens to us that shapes our humanity, but how we react, Keeping Katherine shows the unconditional love that exists in families and the gifts the profoundly disabled can offer to those who try to understand them.

Preț: 97.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.71€ • 19.59$ • 15.48£

18.71€ • 19.59$ • 15.48£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400052011

ISBN-10: 1400052017

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 19 BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: HARMONY

ISBN-10: 1400052017

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 19 BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: HARMONY

Notă biografică

Susan Zimmermann lives in Colorado with her husband and four children. She is the author of Writing to Heal the Soul and a coauthor of The 7 Keys to Comprehension and The Mosaic of Thought.

Extras

Chapter 1

Our stories shape us. They give us our songs and our silence. When they are full of joy, they allow us to soar. When they are full of pain, they allow us to journey into the darkness of our souls where we meet ourselves, sometimes for the first time. They destroy us and allow us to rebuild. We must share our stories. They are our gifts.

Before dawn on September 2, 1979, contractions began. I lay in bed with three pillows piled under my legs and drank hot tea. Paul brought me a bowl of honeydew and ran a bath. I sucked the juice from the melon. Maybe it’s false labor, I thought. The baby’s due date was two weeks away. I had just turned twenty-eight. I’d been married for five years.

I soaked in the old tub with ornate feet and took deep, slow breaths. Leaning back, I rubbed my hands across my tight belly and thought about the child I didn’t know, but already adored.

Six years earlier, Paul had spotted me across the aisle in the Yale Law Library, during our first month of law school. I sat, wearing overalls and a T-shirt, with one leg slung over the arm of the chair and my face buried in a book. My dark hair curled short around my head. I looked like a country kid visiting the city and probably seemed young and naïve compared to many of the students who, unlike me, actually wanted to be lawyers. I dove into law school but never knew quite why I was there or where it would lead.

I’d gone to Woodsfield High School, a small school in southeastern Ohio. The French teacher didn’t speak French. Band, football, and cheerleading took priority over academics. I’d gone on to college at Chapel Hill in North Carolina, where I’d done well, but Yale was different. Students seemed to talk and think faster. Many already had law firm résumés and big plans for their futures.

When I started at Yale, my dad took me aside and said, “Susan, there will be a lot of people there who are smarter than you, more brilliant, better educated. You can make up for a lot with plain hard work. If you plan on nintey-nine percent perspiration and one percent inspiration, you’ll do fine.”

One day early in the fall of 1973, I walked through the main corridor in sweat clothes. Paul stopped me and asked if I’d like to run. We headed out Prospect Street past the Forestry and Divinity Schools to Whitney Avenue.

At first I viewed him as a friend and running partner, nothing more. When I entered his dorm room, Bach or Vivaldi played in the background. He wore thick black glasses and had a Charlie Chaplin mustache. He went to church on Sundays and spent his spare time reading G. K. Chesterton and Samuel Johnson. He’d gone to a Catholic military school in D.C. and on to Harvard. One hot day, after a long run together, he grabbed the end of his

T-shirt, took off his glasses, and wiped the sweat from his eyes. I began to fall in love with him in that brief moment before he put his glasses back on, as he squinted blindly, revealing an unexpected vulnerability.

The following May, with baroque music playing, we were married in Yale’s Dwight Memorial Chapel, a small Gothic church with well-scuffed wooden floors, stone walls, and stained-glass windows. I wore a veil of Belgian lace from Paul’s grandmother and carried one long-stemmed white rose.

The summer after we married, Paul and I lived in D.C. and worked at U.S. Customs writing legal opinions on how U.S. tariffs applied to a bizarre array of imported goods. Every morning, we bicycled to work, a seven-mile route that wound through Rock Creek Park and past the D.C. zoo. It gave us a fresh start to the day. Paul insisted I wear a motorcycle helmet—a heavy black thing with red lightning strikes on the sides. Paul wore a hockey helmet with a lot more ventilation. By late afternoon, when we trekked home, every cool breath had died. Car exhausts puffed. Heat lay over the city like a hairnet. I rode irritated by the commuters who pointed at me from their air-conditioned cars, feeling like I had a sauna on my head. Most days, by the time we got to the house, I had a headache and a bad attitude.

It was a tug-of-war summer. We were in love, but also strong-willed, which made the necessary compromises of marriage difficult. There was an up-and-down quality to time. The morning bike rides were our daily dose of freshness. The evening rides brought out the tensions.

After graduating from law school in 1976, the Rockies and sunshine drew us back to Denver, where Paul and I had spent a previous summer as law clerks. We worked at downtown firms and spent many weekends bagging peaks in the high country.

Paul hiked for the sheer adventure. He liked to bushwhack as much as I liked a trail. He always searched for circle routes and never minded rambling around for half a day. For me, there were too many “circle routes to nowhere,” but Paul always got us home safely.

Our house sat across the street from Mercy Hospital, near City Park. A steady stream of hookers worked Colfax Avenue a block away. Houses that had been renovated to pristine condition stood next to places that had torn sofas on their front porches.

Mercy Hospital’s parking lot was out our front door. Paul built a white picket fence to hide the parking-lot view and erected a six-foot fence around our postage-stamp-sized backyard. We painted the interior “Navajo white” from basement to attic, ripped up the green shag carpet, and toted railroad ties and flagstone to build patios and vegetable gardens. For weeks, we scrounged lower downtown for old bricks to add inexpensive character to our landscaping. This was how we built our life as a young married couple, before Katherine.

The warm water didn’t soothe the contractions away. Leaning back in the tub, I closed my eyes and practiced Lamaze breathing. I ran more hot water so only the top of my belly broke the surface. I dreaded the pain that was to come, certain that at the critical moment I’d forget the right breathing technique. I wanted more time to clean the house and get the baby’s room ready.

That Sunday morning, we walked the short distance through the parking lot to Mercy Hospital. The first few hours passed uneventfully; then the contractions came closer. After hours of pushing, the baby wouldn’t come out. Finally, the doctor used forceps. There were no marks.

With Katherine’s first cry, I felt a new dimension. My life would be forever deepened. My body shook from the strain of three hours of pushing. Blood vessels throughout my face had burst. The doctor held her up covered with mucus. Never had I seen anything so hideously beautiful. Then they wiped her clean and gently placed her in my arms.

Katherine Rose, an elegant name full of history and power: Katherine—an old family name, the name of queens; and Rose—for Ruzicka, Rose in Czech, Paul’s mother’s maiden name. When we first put the names together, we stopped looking. We had the name. Our Katherine Rose would blossom into a glorious flower.

By this time Paul’s parents, Paul Sr. and Rita, had left D.C. and retired to Colorado. They rushed down from their nearby home in Winter Park to meet Katherine. Paul Sr. stood holding her awkwardly and stared at her delicate features. “I’ve never seen a lovelier creature,” he said. Rita wrapped Katherine in soft pink blankets, sat in the tan hospital chair with metal arms, and began a conversation that was to last for years.

It was clear to me that I had been waiting for Katherine all my life. The connection went beyond words to a place I’d never known. She gave me the joy of complete and uncomplicated love—a love that grew stronger with each diaper change and midnight feeding.

Every morning Paul and I brought her into bed with us. Her broad smiles and playful chortles remain imprinted on my mind. Her early “Mamas” and “Dadas” still ring in my head.

I took a break from work. Returning to corporate law now held little appeal. I headed a project to plant trees in our neighborhood, joined a babysitting co-op, and watched as Kat grew. She learned to sit and say a few words. She played with the activity center attached to her crib, making it clang and whir like any baby would. She greeted me with outstretched arms and laughter. In her baby book, I wrote: “How Katherine laughs when you make funny noises at her or blow on her tummy. She is delighted when she is left sitting up and playing with her toys. She is thrilled by splashing and kicking in the tub, but her blue doll brings her more joy than anything else.”

When Kat was seven months old, I found a part-time job working for the state Department of Regulatory Agencies. The work was interesting but not overly demand-ing—a perfect balance, three workdays, four days with Katherine.

Several months later, I stopped writing in Katherine’s baby book. I told myself I was too busy. Much later, I realized the small landmarks of her progress were no longer there to be charted.

When do we first know our lives are forever changed? When do our hearts sink to our stomachs, our breaths catch in our throats, our bodies turn leaden? What do we do when we know there is nothing we can do?

Our stories shape us. They give us our songs and our silence. When they are full of joy, they allow us to soar. When they are full of pain, they allow us to journey into the darkness of our souls where we meet ourselves, sometimes for the first time. They destroy us and allow us to rebuild. We must share our stories. They are our gifts.

Before dawn on September 2, 1979, contractions began. I lay in bed with three pillows piled under my legs and drank hot tea. Paul brought me a bowl of honeydew and ran a bath. I sucked the juice from the melon. Maybe it’s false labor, I thought. The baby’s due date was two weeks away. I had just turned twenty-eight. I’d been married for five years.

I soaked in the old tub with ornate feet and took deep, slow breaths. Leaning back, I rubbed my hands across my tight belly and thought about the child I didn’t know, but already adored.

Six years earlier, Paul had spotted me across the aisle in the Yale Law Library, during our first month of law school. I sat, wearing overalls and a T-shirt, with one leg slung over the arm of the chair and my face buried in a book. My dark hair curled short around my head. I looked like a country kid visiting the city and probably seemed young and naïve compared to many of the students who, unlike me, actually wanted to be lawyers. I dove into law school but never knew quite why I was there or where it would lead.

I’d gone to Woodsfield High School, a small school in southeastern Ohio. The French teacher didn’t speak French. Band, football, and cheerleading took priority over academics. I’d gone on to college at Chapel Hill in North Carolina, where I’d done well, but Yale was different. Students seemed to talk and think faster. Many already had law firm résumés and big plans for their futures.

When I started at Yale, my dad took me aside and said, “Susan, there will be a lot of people there who are smarter than you, more brilliant, better educated. You can make up for a lot with plain hard work. If you plan on nintey-nine percent perspiration and one percent inspiration, you’ll do fine.”

One day early in the fall of 1973, I walked through the main corridor in sweat clothes. Paul stopped me and asked if I’d like to run. We headed out Prospect Street past the Forestry and Divinity Schools to Whitney Avenue.

At first I viewed him as a friend and running partner, nothing more. When I entered his dorm room, Bach or Vivaldi played in the background. He wore thick black glasses and had a Charlie Chaplin mustache. He went to church on Sundays and spent his spare time reading G. K. Chesterton and Samuel Johnson. He’d gone to a Catholic military school in D.C. and on to Harvard. One hot day, after a long run together, he grabbed the end of his

T-shirt, took off his glasses, and wiped the sweat from his eyes. I began to fall in love with him in that brief moment before he put his glasses back on, as he squinted blindly, revealing an unexpected vulnerability.

The following May, with baroque music playing, we were married in Yale’s Dwight Memorial Chapel, a small Gothic church with well-scuffed wooden floors, stone walls, and stained-glass windows. I wore a veil of Belgian lace from Paul’s grandmother and carried one long-stemmed white rose.

The summer after we married, Paul and I lived in D.C. and worked at U.S. Customs writing legal opinions on how U.S. tariffs applied to a bizarre array of imported goods. Every morning, we bicycled to work, a seven-mile route that wound through Rock Creek Park and past the D.C. zoo. It gave us a fresh start to the day. Paul insisted I wear a motorcycle helmet—a heavy black thing with red lightning strikes on the sides. Paul wore a hockey helmet with a lot more ventilation. By late afternoon, when we trekked home, every cool breath had died. Car exhausts puffed. Heat lay over the city like a hairnet. I rode irritated by the commuters who pointed at me from their air-conditioned cars, feeling like I had a sauna on my head. Most days, by the time we got to the house, I had a headache and a bad attitude.

It was a tug-of-war summer. We were in love, but also strong-willed, which made the necessary compromises of marriage difficult. There was an up-and-down quality to time. The morning bike rides were our daily dose of freshness. The evening rides brought out the tensions.

After graduating from law school in 1976, the Rockies and sunshine drew us back to Denver, where Paul and I had spent a previous summer as law clerks. We worked at downtown firms and spent many weekends bagging peaks in the high country.

Paul hiked for the sheer adventure. He liked to bushwhack as much as I liked a trail. He always searched for circle routes and never minded rambling around for half a day. For me, there were too many “circle routes to nowhere,” but Paul always got us home safely.

Our house sat across the street from Mercy Hospital, near City Park. A steady stream of hookers worked Colfax Avenue a block away. Houses that had been renovated to pristine condition stood next to places that had torn sofas on their front porches.

Mercy Hospital’s parking lot was out our front door. Paul built a white picket fence to hide the parking-lot view and erected a six-foot fence around our postage-stamp-sized backyard. We painted the interior “Navajo white” from basement to attic, ripped up the green shag carpet, and toted railroad ties and flagstone to build patios and vegetable gardens. For weeks, we scrounged lower downtown for old bricks to add inexpensive character to our landscaping. This was how we built our life as a young married couple, before Katherine.

The warm water didn’t soothe the contractions away. Leaning back in the tub, I closed my eyes and practiced Lamaze breathing. I ran more hot water so only the top of my belly broke the surface. I dreaded the pain that was to come, certain that at the critical moment I’d forget the right breathing technique. I wanted more time to clean the house and get the baby’s room ready.

That Sunday morning, we walked the short distance through the parking lot to Mercy Hospital. The first few hours passed uneventfully; then the contractions came closer. After hours of pushing, the baby wouldn’t come out. Finally, the doctor used forceps. There were no marks.

With Katherine’s first cry, I felt a new dimension. My life would be forever deepened. My body shook from the strain of three hours of pushing. Blood vessels throughout my face had burst. The doctor held her up covered with mucus. Never had I seen anything so hideously beautiful. Then they wiped her clean and gently placed her in my arms.

Katherine Rose, an elegant name full of history and power: Katherine—an old family name, the name of queens; and Rose—for Ruzicka, Rose in Czech, Paul’s mother’s maiden name. When we first put the names together, we stopped looking. We had the name. Our Katherine Rose would blossom into a glorious flower.

By this time Paul’s parents, Paul Sr. and Rita, had left D.C. and retired to Colorado. They rushed down from their nearby home in Winter Park to meet Katherine. Paul Sr. stood holding her awkwardly and stared at her delicate features. “I’ve never seen a lovelier creature,” he said. Rita wrapped Katherine in soft pink blankets, sat in the tan hospital chair with metal arms, and began a conversation that was to last for years.

It was clear to me that I had been waiting for Katherine all my life. The connection went beyond words to a place I’d never known. She gave me the joy of complete and uncomplicated love—a love that grew stronger with each diaper change and midnight feeding.

Every morning Paul and I brought her into bed with us. Her broad smiles and playful chortles remain imprinted on my mind. Her early “Mamas” and “Dadas” still ring in my head.

I took a break from work. Returning to corporate law now held little appeal. I headed a project to plant trees in our neighborhood, joined a babysitting co-op, and watched as Kat grew. She learned to sit and say a few words. She played with the activity center attached to her crib, making it clang and whir like any baby would. She greeted me with outstretched arms and laughter. In her baby book, I wrote: “How Katherine laughs when you make funny noises at her or blow on her tummy. She is delighted when she is left sitting up and playing with her toys. She is thrilled by splashing and kicking in the tub, but her blue doll brings her more joy than anything else.”

When Kat was seven months old, I found a part-time job working for the state Department of Regulatory Agencies. The work was interesting but not overly demand-ing—a perfect balance, three workdays, four days with Katherine.

Several months later, I stopped writing in Katherine’s baby book. I told myself I was too busy. Much later, I realized the small landmarks of her progress were no longer there to be charted.

When do we first know our lives are forever changed? When do our hearts sink to our stomachs, our breaths catch in our throats, our bodies turn leaden? What do we do when we know there is nothing we can do?

Recenzii

“Susan Zimmermann’s deeply moving book will touch all people, not only parents. Her courage, her joy, and her hope reach through her tragedy and offer us all a way of life that is creative, no matter what the circumstances.” —Madeleine L’Engle, Newbery Award–winning author

“Susan Zimmermann portrays, with honesty, passion, and wisdom, a chapter of her life that is both deeply terrifying and wholly inspiring. It is a story of loss and gain, pain and joy, and—above all—profound truth. It is a story with the power to change your life.” —T. A. Barron, author of Heartlight, The Ancient One, and The Lost Years of Merlin series

“Susan’s story—and Kat’s—is a profound gift. Susan reminds us that it isn’t what happens to us that determines our life, but how we respond to it.” —Marilyn Van Derbur, author of Miss America By Day

“Susan Zimmermann portrays, with honesty, passion, and wisdom, a chapter of her life that is both deeply terrifying and wholly inspiring. It is a story of loss and gain, pain and joy, and—above all—profound truth. It is a story with the power to change your life.” —T. A. Barron, author of Heartlight, The Ancient One, and The Lost Years of Merlin series

“Susan’s story—and Kat’s—is a profound gift. Susan reminds us that it isn’t what happens to us that determines our life, but how we respond to it.” —Marilyn Van Derbur, author of Miss America By Day

Descriere

What happens when you have life on a string and then everything changes? The author tells the story of life with her daughter, Katherine, who developed Rett Syndrome without warning. This is the story of a soul-searching journey through grief, loss, hope, anger, and despair to a place of unconditional love.