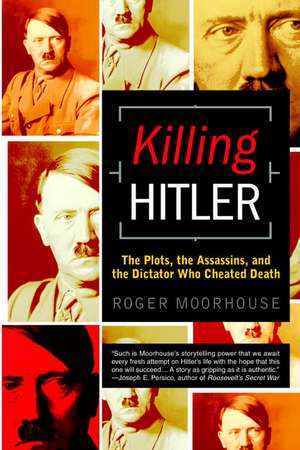

Killing Hitler: The Plots, the Assassins, and the Dictator Who Cheated Death

Autor Roger Moorhouseen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2007

Disraeli once declared that “assassination never changed anything,” and yet the idea that World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust might have been averted with a single bullet or bomb has remained a tantalizing one for half a century. What historian Roger Moorhouse reveals in Killing Hitler is just how close–and how often–history came to taking a radically different path between Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and his ignominious suicide.

Few leaders, in any century, can have been the target of so many assassination attempts, with such momentous consequences in the balance. Hitler’s almost fifty would-be assassins ranged from simple craftsmen to high-ranking soldiers, from the apolitical to the ideologically obsessed, from Polish Resistance fighters to patriotic Wehrmacht officers, and from enemy agents to his closest associates. And yet, up to now, their exploits have remained virtually unknown, buried in dusty official archives and obscure memoirs. This, then, for the first time in a single volume, is their story.

A story of courage and ingenuity and, ultimately, failure, ranging from spectacular train derailments to the world’s first known suicide bomber, explaining along the way why the British at one time declared that assassinating Hitler would be “unsporting,” and why the ruthless murderer Joseph Stalin was unwilling to order his death.

It is also the remarkable, terrible story of the survival of a tyrant against all the odds, an evil dictator whose repeated escapes from almost certain death convinced him that he was literally invincible–a conviction that had appalling consequences for millions.

Preț: 136.04 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.03€ • 26.90$ • 21.67£

26.03€ • 26.90$ • 21.67£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553382556

ISBN-10: 0553382551

Pagini: 374

Dimensiuni: 155 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553382551

Pagini: 374

Dimensiuni: 155 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Bantam Books

Notă biografică

Roger Moorhouse studied history at the University of London and is currently reading for a PhD in modern German history at the University of Strathclyde. He was co-author with Norman Davies of Microcosm: Portrait of a Central European City and is a regular contributor to BBC History Magazine. He is married with two children and lives in Buckinghamshire, England.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Prologue

Munich, Thursday, 8 November 1923, 8:30 p.m.

Few of the guests would have noticed the sallow-faced young man who entered the beer hall that evening. All of the great and the good of Munich were there: bankers, businessmen, newspaper editors, and politicians. They had gathered to hear an address commemorating the fifth anniversary of the November Revolution, given by the newly appointed state commissioner for Bavaria. They had expected a forceful denunciation of Marxism, an explanation of the administration’s policies, perhaps even the advocacy of a restoration of the Bavarian monarchy. What they got was an attempted revolution.

The hall, the Bürgerbräukeller, was one of the largest in Munich. Located on the east side of the river Isar, which bisected the city, it was a cavernous room that belied the cozy image of the traditional beer hall. With a high ceiling, ornate chandeliers, and a wide balcony running down one side, it could accommodate around three thousand people seated on either side of long wooden trestle tables. As such, it was one of the primary venues in Munich for public lectures and political meetings. This evening, it was packed to the rafters. The doors had been closed already at 7:15 p.m. to prevent overcrowding, and the disappointed milled in the drizzle on the street outside.

The man loitering at the rear of the hall would have been known to many of the guests present that night. A pale individual in his mid-thirties, with sharp cheekbones, a toothbrush mustache, and striking blue eyes, Adolf Hitler was the leader of a local extreme nationalist group that called itself the National Socialist German Workers Party–or Nazis for short. He was renowned as a talented and inspirational public speaker, captivating his audiences with his impassioned and intemperate lectures on German politics. He had already spoken at the Bürgerbräukeller numerous times. This evening, however, he had come as an unlikely revolutionary. Dressed in a poorly cut black morning suit with flowing tails, his hair slicked close to his scalp and falling in unruly strands across his forehead, he looked more like an overworked waiter or an undertaker.

Nonetheless, about half an hour into the keynote speech, he began to make his way forward at the head of a phalanx of fellow putschists. As a detachment of Nazi storm troopers appeared, dragging a machine gun into the hall entrance, the distinguished speaker on the podium tailed off into silence. Whispers spread around the cavernous hall, drinkers craned their necks to see what was going on, women fainted, and tables were upended. In the commotion, Hitler clambered onto a chair, fired a pistol shot into the ceiling, and called for silence. “The National Revolution,” he announced, “has begun.”

After a brief speech, he posted his troops and bodyguards at the exits and persuaded three of the honored guests present–who, between them, effectively ruled Munich–to retire with him to an adjoining room. There, in wild excitement, Hitler harangued his captive audience, announcing the formation of a new government with himself at its head, and promising ministerial posts for those present if they agreed to cooperate. Waving his gun, he warned melodramatically: “I have four shots in my pistol. Three for my collaborators if they abandon me. The last is for myself.” With that, he put the gun to his temple, declaring: “If I am not victorious by tomorrow afternoon, I shall be a dead man.”

Germany in 1923 had endured five years of chaos. Emerging from defeat in the maelstrom of World War One, its fledgling democracy was assailed from both left and right, and undermined by a disintegrating economy. Political radicalism was fueled by a spiral of debilitating hyperinflation. By 1920, the price index stood at nearly 15 times its value in 1913; two years later it was approaching 350. 1923 was to be a crisis year. In the west, the French occupied the Ruhr in response to the German nonpayment of reparations, sparking passive resistance, strikes, and hunger riots. Elsewhere, disgruntled army units mutinied at Küstrin, east of Berlin, and in the subsequent months, pro-communist governments were established in Saxony and Thuringia. For a time, the instability appeared to be terminal, and all the while, the economy was heading into free fall. Prices in January 1923 were more than 2,500 times higher than they had been in 1913. By December they were 1.25 billion times higher.3 The hyperinflation had become a full-scale currency collapse. The humble loaf of bread could cost over 400 billion marks, and many households found it more economical to burn money than attempt to use it to buy kindling or coal. Most Germans faced financial ruin.

The situation in Bavaria was no less fraught. There, the upheaval of the previous few years had awakened thoughts of separatism. The regional government in Munich was already plowing its own furrow, ignoring Berlin’s strictures when it chose to and tolerating the radical right. Indeed, the two power bases in the province, the monarchist “old right” of the government and the revolutionary “new right” of Hitler and his allies, existed in a curiously symbiotic relationship. Both held the government in Berlin in contempt and were keen to cooperate in their intrigues against it. Both, too, were impatient to raise the standard of revolt. However, their visions of the would-be revolution differed widely. Put simply, the “old right” wanted to create an independent Bavarian government, while the “new right” wanted to replace the Reich government. One wanted to defect from Berlin, and the other wanted to march on it.

In the Bürgerbräukeller that evening, Hitler appeared finally to have succeeded in persuading Munich’s ruling triumvirate to join in his vision of a revolution. About an hour after he had entered the hall, he returned to the podium, accompanied by his new confederates and the freshly arrived former army quartermaster, General Ludendorff. All five shook hands repeatedly and made short speeches to the assembled throng, announcing their new roles and their earnest intentions to cooperate. As they finished, the crowd, enthused by what they had heard, broke into an impromptu rendition of “Deutschland über Alles.” One eyewitness recalled that the crowd had been “turned inside-out” by Hitler’s words and that “it had almost something of hocus-pocus about it.”Ominously, Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s secretary, then began calling names from a list of those present who were to be detained for interrogation and trial. With that, the remainder of the audience was allowed to leave, while sympathizers began arriving from around the city. Hitler, it appeared, had succeeded.

Beyond the confines of the beer hall, however, the putsch was proceeding less well. Troops loyal to Hitler had scored some early victories. They had been bolstered by the defection of the cadets of the Infantry School and had succeeded in occupying the three main beer halls in Munich. Elsewhere, they had taken over the Bavarian War Ministry and the offices of the influential Münchener Post newspaper. But as the night progressed, they achieved no more significant successes. Their own incompetence and the stiffened resolve of their opponents combined to prevent them from seizing other key buildings and barracks.

Moreover, the authorities in Munich were preparing for a fight. The members of the ruling triumvirate, far from serving the putsch, had now repudiated it and were directing the resistance. The government, transferred to Regensburg for its own safety had banned the morning newspapers and drafted in military reinforcements from the provinces. Across the city, its forces were now fully apprised of events and had specific orders on how the revolt was to be countered. As the would-be revolutionaries in the beer hall settled down for a long night, succored by a generous supply of beer and bread rolls, they were still optimistic. In truth, they had already lost the initiative and now faced a precarious stalemate.

The following day, as a cold dawn broke, the putschists finally recognized that their initial attempt to storm the bastions of power had failed. A British correspondent from the Times found his way to the Bürgerbräukeller that morning, where he discovered Ludendorff and Hitler in a small upstairs room. Hitler, he wrote, was “dead-tired” and barely seemed to fill the part of the revolutionary: “this little man in an old waterproof coat with a revolver at his hip, unshaven and with disordered hair, and so hoarse that he could scarcely speak.” Ludendorff, in turn, was “anxious and preoccupied.”

The putschists were considering their options. One suggested that the Bavarian crown prince could be induced to lend the revolt his support. Another proposed a tactical withdrawal to continue their resistance from the town of Rosenheim near the Austrian border. In the confusion, meanwhile, orders were delayed, and further troops drifted away from their positions, considering their cause to be lost. By midmorning, however, the idea of a demonstration march through the city was mooted. That way, the putschists besieged at the War Ministry could be relieved and the enthusiasm of the local population could be harnessed. The stalemate could be broken. After all, it was thought, the army would surely not turn its machine guns on Ludendorff, one of the most prominent generals of the First World War. The hotheads even considered that a march on Berlin could be attempted, in imitation of Mussolini. “We would go into the city,” Hitler later recalled, “to win the people to our side.”

Shortly before noon that morning, a column of around two thousand men, armed and defiant, stepped out of the Bürgerbräukeller and headed for the center of the city. In the front rank, beneath the swastika banner and the flag of imperial Germany, Hitler marched with Ludendorff on one side and his fellow conspirator Erwin von Scheubner-Richter on the other. Alongside them were Hitler’s bodyguard, Ulrich Graf, a bull-necked apprentice butcher and amateur wrestler; the Nazi “philosopher” Gottfried Feder; and the leader of the storm troopers, Hermann Göring, resplendent in a full-length leather coat, with his Pour le Mérite–Germany’s highest military award–visible at his throat. Behind them, the ranks of Hitler’s security force, the Munich storm troopers and the paramilitary Bund Oberland marched four abreast, followed by a car bristling with weaponry. Bringing up the rear was a ragtag collection of students, tradesmen, and fellow travelers, many inspired by the events of the previous night, many long-term disciples. Some marched smartly in uniform, some donned their medals from the Great War, and others shuffled along wearing work overalls.

Jeered and cheered by a curious Munich public, the putschists moved steadily on, sustaining themselves by singing nationalist songs. Close to the river, they encountered their first serious obstacle when they confronted a police cordon on the Ludwigsbrücke. With bayonets leveled and exhortations to the policemen not to fire on their comrades, they swept the picket aside and continued unhindered across the bridge and into the heart of Munich. Proceeding through the Isartor, they came to the Marienplatz, where large crowds had gathered to watch events unfold. From there, they turned north in the direction of the Odeonsplatz, beyond which the War Ministry was located. As they approached the Feldherrnhalle, however, barely fifty meters from their target, they were confronted by a second, larger police presence. Linking arms, they advanced, some singing, some with bayonets at the ready, down the Residenzstrasse.

This time, the police would not be brushed aside. As the two forces met, a shot rang out and the police opened fire. In the chaos, as a brief firefight ensued, the front rank of putschists fell to the ground, while the remainder fled. After a couple of minutes, only the dead and wounded remained. Göring had been shot in the groin. Scheubner-Richter, to Hitler’s left, fell mortally wounded with a bullet in the chest. Graf, who had shielded Hitler from the onslaught, took numerous bullets and was gravely injured. Four Munich policemen had been killed as well as a further thirteen of Hitler’s followers. The youngest of them, Karl Laforce, was barely nineteen.

Hitler, meanwhile, had fallen in the melee, believing himself to have been shot. In fact, though wild rumors quickly circulated that he had been killed, he had merely suffered a dislocated shoulder from being violently pulled to the ground by the dying Scheubner-Richter.7 In the aftermath, he struggled to his feet and found his way to a nearby square, where supporters spirited him to a waiting car and south toward Austria. Later that day, after an eventful escape from Munich, he arrived at the house of his fellow putschist Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, in Uffing, where he was tended by a sympathetic doctor. Two days later, in the early evening of 11 November, the police finally tracked him down. According to one account, Hitler broke down when he heard of the police’s arrival. With a cry of “Now all is lost!” he reached for his pistol.Yet, rather than turn the gun on himself, as he had promised to do at the Bürgerbräukeller, Hitler submitted meekly. The arresting officer found him in a bedroom, dressed in pajamas, waiting calmly in sullen silence.

Hitler had escaped death but had nonetheless failed. His “National Revolution” had been crushed, his party outlawed, and his loyal henchmen killed, arrested, or in exile. Tried for high treason the following spring, he was sentenced to five years’ detention in the fortress at Landsberg. Contemporary opinion concluded that the name of Adolf Hitler had been a footnote in history, a chimera, soon to rank alongside countless other crackpots, radicals, and failed revolutionaries. He was haughtily dismissed by the Times as a “house decorator and demagogue.”Many took to speaking of him only in the past tense. The author Stefan Zweig, for example, considered that Hitler had fallen back “into oblivion.”

Hitler himself was immune to such prophecies, for he considered himself to be subject to another, higher calling. “You may pronounce us guilty a thousand times over,” he railed to the state prosecutor at his trial, “but the goddess of the eternal court of history will smile and tear to tatters . . . the sentence of this court.” The bullets of the Bavarian police that had routed his forces in Munich had also given him his first brush with providence. He emerged from that experience, and from his imprisonment at Landsberg, with the unshakable belief that his life had been preserved so that he might fulfill a “historic destiny” to save Germany. He emerged as a man with a mission.

1

From the Hardcover edition.

Munich, Thursday, 8 November 1923, 8:30 p.m.

Few of the guests would have noticed the sallow-faced young man who entered the beer hall that evening. All of the great and the good of Munich were there: bankers, businessmen, newspaper editors, and politicians. They had gathered to hear an address commemorating the fifth anniversary of the November Revolution, given by the newly appointed state commissioner for Bavaria. They had expected a forceful denunciation of Marxism, an explanation of the administration’s policies, perhaps even the advocacy of a restoration of the Bavarian monarchy. What they got was an attempted revolution.

The hall, the Bürgerbräukeller, was one of the largest in Munich. Located on the east side of the river Isar, which bisected the city, it was a cavernous room that belied the cozy image of the traditional beer hall. With a high ceiling, ornate chandeliers, and a wide balcony running down one side, it could accommodate around three thousand people seated on either side of long wooden trestle tables. As such, it was one of the primary venues in Munich for public lectures and political meetings. This evening, it was packed to the rafters. The doors had been closed already at 7:15 p.m. to prevent overcrowding, and the disappointed milled in the drizzle on the street outside.

The man loitering at the rear of the hall would have been known to many of the guests present that night. A pale individual in his mid-thirties, with sharp cheekbones, a toothbrush mustache, and striking blue eyes, Adolf Hitler was the leader of a local extreme nationalist group that called itself the National Socialist German Workers Party–or Nazis for short. He was renowned as a talented and inspirational public speaker, captivating his audiences with his impassioned and intemperate lectures on German politics. He had already spoken at the Bürgerbräukeller numerous times. This evening, however, he had come as an unlikely revolutionary. Dressed in a poorly cut black morning suit with flowing tails, his hair slicked close to his scalp and falling in unruly strands across his forehead, he looked more like an overworked waiter or an undertaker.

Nonetheless, about half an hour into the keynote speech, he began to make his way forward at the head of a phalanx of fellow putschists. As a detachment of Nazi storm troopers appeared, dragging a machine gun into the hall entrance, the distinguished speaker on the podium tailed off into silence. Whispers spread around the cavernous hall, drinkers craned their necks to see what was going on, women fainted, and tables were upended. In the commotion, Hitler clambered onto a chair, fired a pistol shot into the ceiling, and called for silence. “The National Revolution,” he announced, “has begun.”

After a brief speech, he posted his troops and bodyguards at the exits and persuaded three of the honored guests present–who, between them, effectively ruled Munich–to retire with him to an adjoining room. There, in wild excitement, Hitler harangued his captive audience, announcing the formation of a new government with himself at its head, and promising ministerial posts for those present if they agreed to cooperate. Waving his gun, he warned melodramatically: “I have four shots in my pistol. Three for my collaborators if they abandon me. The last is for myself.” With that, he put the gun to his temple, declaring: “If I am not victorious by tomorrow afternoon, I shall be a dead man.”

Germany in 1923 had endured five years of chaos. Emerging from defeat in the maelstrom of World War One, its fledgling democracy was assailed from both left and right, and undermined by a disintegrating economy. Political radicalism was fueled by a spiral of debilitating hyperinflation. By 1920, the price index stood at nearly 15 times its value in 1913; two years later it was approaching 350. 1923 was to be a crisis year. In the west, the French occupied the Ruhr in response to the German nonpayment of reparations, sparking passive resistance, strikes, and hunger riots. Elsewhere, disgruntled army units mutinied at Küstrin, east of Berlin, and in the subsequent months, pro-communist governments were established in Saxony and Thuringia. For a time, the instability appeared to be terminal, and all the while, the economy was heading into free fall. Prices in January 1923 were more than 2,500 times higher than they had been in 1913. By December they were 1.25 billion times higher.3 The hyperinflation had become a full-scale currency collapse. The humble loaf of bread could cost over 400 billion marks, and many households found it more economical to burn money than attempt to use it to buy kindling or coal. Most Germans faced financial ruin.

The situation in Bavaria was no less fraught. There, the upheaval of the previous few years had awakened thoughts of separatism. The regional government in Munich was already plowing its own furrow, ignoring Berlin’s strictures when it chose to and tolerating the radical right. Indeed, the two power bases in the province, the monarchist “old right” of the government and the revolutionary “new right” of Hitler and his allies, existed in a curiously symbiotic relationship. Both held the government in Berlin in contempt and were keen to cooperate in their intrigues against it. Both, too, were impatient to raise the standard of revolt. However, their visions of the would-be revolution differed widely. Put simply, the “old right” wanted to create an independent Bavarian government, while the “new right” wanted to replace the Reich government. One wanted to defect from Berlin, and the other wanted to march on it.

In the Bürgerbräukeller that evening, Hitler appeared finally to have succeeded in persuading Munich’s ruling triumvirate to join in his vision of a revolution. About an hour after he had entered the hall, he returned to the podium, accompanied by his new confederates and the freshly arrived former army quartermaster, General Ludendorff. All five shook hands repeatedly and made short speeches to the assembled throng, announcing their new roles and their earnest intentions to cooperate. As they finished, the crowd, enthused by what they had heard, broke into an impromptu rendition of “Deutschland über Alles.” One eyewitness recalled that the crowd had been “turned inside-out” by Hitler’s words and that “it had almost something of hocus-pocus about it.”Ominously, Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s secretary, then began calling names from a list of those present who were to be detained for interrogation and trial. With that, the remainder of the audience was allowed to leave, while sympathizers began arriving from around the city. Hitler, it appeared, had succeeded.

Beyond the confines of the beer hall, however, the putsch was proceeding less well. Troops loyal to Hitler had scored some early victories. They had been bolstered by the defection of the cadets of the Infantry School and had succeeded in occupying the three main beer halls in Munich. Elsewhere, they had taken over the Bavarian War Ministry and the offices of the influential Münchener Post newspaper. But as the night progressed, they achieved no more significant successes. Their own incompetence and the stiffened resolve of their opponents combined to prevent them from seizing other key buildings and barracks.

Moreover, the authorities in Munich were preparing for a fight. The members of the ruling triumvirate, far from serving the putsch, had now repudiated it and were directing the resistance. The government, transferred to Regensburg for its own safety had banned the morning newspapers and drafted in military reinforcements from the provinces. Across the city, its forces were now fully apprised of events and had specific orders on how the revolt was to be countered. As the would-be revolutionaries in the beer hall settled down for a long night, succored by a generous supply of beer and bread rolls, they were still optimistic. In truth, they had already lost the initiative and now faced a precarious stalemate.

The following day, as a cold dawn broke, the putschists finally recognized that their initial attempt to storm the bastions of power had failed. A British correspondent from the Times found his way to the Bürgerbräukeller that morning, where he discovered Ludendorff and Hitler in a small upstairs room. Hitler, he wrote, was “dead-tired” and barely seemed to fill the part of the revolutionary: “this little man in an old waterproof coat with a revolver at his hip, unshaven and with disordered hair, and so hoarse that he could scarcely speak.” Ludendorff, in turn, was “anxious and preoccupied.”

The putschists were considering their options. One suggested that the Bavarian crown prince could be induced to lend the revolt his support. Another proposed a tactical withdrawal to continue their resistance from the town of Rosenheim near the Austrian border. In the confusion, meanwhile, orders were delayed, and further troops drifted away from their positions, considering their cause to be lost. By midmorning, however, the idea of a demonstration march through the city was mooted. That way, the putschists besieged at the War Ministry could be relieved and the enthusiasm of the local population could be harnessed. The stalemate could be broken. After all, it was thought, the army would surely not turn its machine guns on Ludendorff, one of the most prominent generals of the First World War. The hotheads even considered that a march on Berlin could be attempted, in imitation of Mussolini. “We would go into the city,” Hitler later recalled, “to win the people to our side.”

Shortly before noon that morning, a column of around two thousand men, armed and defiant, stepped out of the Bürgerbräukeller and headed for the center of the city. In the front rank, beneath the swastika banner and the flag of imperial Germany, Hitler marched with Ludendorff on one side and his fellow conspirator Erwin von Scheubner-Richter on the other. Alongside them were Hitler’s bodyguard, Ulrich Graf, a bull-necked apprentice butcher and amateur wrestler; the Nazi “philosopher” Gottfried Feder; and the leader of the storm troopers, Hermann Göring, resplendent in a full-length leather coat, with his Pour le Mérite–Germany’s highest military award–visible at his throat. Behind them, the ranks of Hitler’s security force, the Munich storm troopers and the paramilitary Bund Oberland marched four abreast, followed by a car bristling with weaponry. Bringing up the rear was a ragtag collection of students, tradesmen, and fellow travelers, many inspired by the events of the previous night, many long-term disciples. Some marched smartly in uniform, some donned their medals from the Great War, and others shuffled along wearing work overalls.

Jeered and cheered by a curious Munich public, the putschists moved steadily on, sustaining themselves by singing nationalist songs. Close to the river, they encountered their first serious obstacle when they confronted a police cordon on the Ludwigsbrücke. With bayonets leveled and exhortations to the policemen not to fire on their comrades, they swept the picket aside and continued unhindered across the bridge and into the heart of Munich. Proceeding through the Isartor, they came to the Marienplatz, where large crowds had gathered to watch events unfold. From there, they turned north in the direction of the Odeonsplatz, beyond which the War Ministry was located. As they approached the Feldherrnhalle, however, barely fifty meters from their target, they were confronted by a second, larger police presence. Linking arms, they advanced, some singing, some with bayonets at the ready, down the Residenzstrasse.

This time, the police would not be brushed aside. As the two forces met, a shot rang out and the police opened fire. In the chaos, as a brief firefight ensued, the front rank of putschists fell to the ground, while the remainder fled. After a couple of minutes, only the dead and wounded remained. Göring had been shot in the groin. Scheubner-Richter, to Hitler’s left, fell mortally wounded with a bullet in the chest. Graf, who had shielded Hitler from the onslaught, took numerous bullets and was gravely injured. Four Munich policemen had been killed as well as a further thirteen of Hitler’s followers. The youngest of them, Karl Laforce, was barely nineteen.

Hitler, meanwhile, had fallen in the melee, believing himself to have been shot. In fact, though wild rumors quickly circulated that he had been killed, he had merely suffered a dislocated shoulder from being violently pulled to the ground by the dying Scheubner-Richter.7 In the aftermath, he struggled to his feet and found his way to a nearby square, where supporters spirited him to a waiting car and south toward Austria. Later that day, after an eventful escape from Munich, he arrived at the house of his fellow putschist Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, in Uffing, where he was tended by a sympathetic doctor. Two days later, in the early evening of 11 November, the police finally tracked him down. According to one account, Hitler broke down when he heard of the police’s arrival. With a cry of “Now all is lost!” he reached for his pistol.Yet, rather than turn the gun on himself, as he had promised to do at the Bürgerbräukeller, Hitler submitted meekly. The arresting officer found him in a bedroom, dressed in pajamas, waiting calmly in sullen silence.

Hitler had escaped death but had nonetheless failed. His “National Revolution” had been crushed, his party outlawed, and his loyal henchmen killed, arrested, or in exile. Tried for high treason the following spring, he was sentenced to five years’ detention in the fortress at Landsberg. Contemporary opinion concluded that the name of Adolf Hitler had been a footnote in history, a chimera, soon to rank alongside countless other crackpots, radicals, and failed revolutionaries. He was haughtily dismissed by the Times as a “house decorator and demagogue.”Many took to speaking of him only in the past tense. The author Stefan Zweig, for example, considered that Hitler had fallen back “into oblivion.”

Hitler himself was immune to such prophecies, for he considered himself to be subject to another, higher calling. “You may pronounce us guilty a thousand times over,” he railed to the state prosecutor at his trial, “but the goddess of the eternal court of history will smile and tear to tatters . . . the sentence of this court.” The bullets of the Bavarian police that had routed his forces in Munich had also given him his first brush with providence. He emerged from that experience, and from his imprisonment at Landsberg, with the unshakable belief that his life had been preserved so that he might fulfill a “historic destiny” to save Germany. He emerged as a man with a mission.

1

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Compelling.... a page-turner for WWII buffs as well as anyone with a passion for the underbelly of political power in one of the last century's darkest regimes."—Publishers Weekly

“Such is Moorhouse’s storytelling power that we await every fresh attempt on Hitler’s life with the hope that this one will succeed….A story as gripping as it is authentic.” —Joseph E. Persico, author of Roosevelt’s Secret War

“Such is Moorhouse’s storytelling power that we await every fresh attempt on Hitler’s life with the hope that this one will succeed….A story as gripping as it is authentic.” —Joseph E. Persico, author of Roosevelt’s Secret War

Descriere

For the first time in one enthralling book, here is the incredible true storyof the numerous attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler and change the course ofhistory.