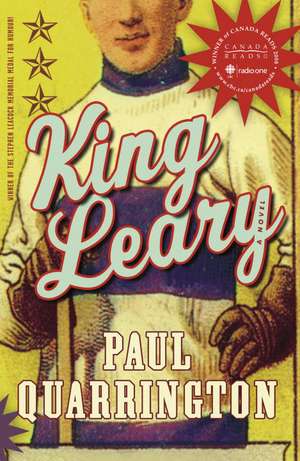

King Leary

Autor Paul Quarringtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2007

"A dazzling display of fictional footwork… The author has not written just another hockey novel; he has turned hockey in a metaphor for magic." Maclean's

Percival Leary was once the King of the Ice, one of hockey's greatest heroes. Now, in the South Grouse Nursing Home, where he shares a room with Edmund "Blue" Hermann, the antagonistic and alcoholic reporter who once chronicled his career, Leary looks back on his tumultuous life and times: his days at the boys' reformatory when he burned down a house; the four mad monks who first taught him to play hockey; and the time he executed the perfect "St. Louis Whirlygig" to score the winning goal in the 1919 Stanley Cup final.

Now all but forgotten, Leary is only a legend in his own mind until a high-powered advertising agency decides to feature him in a series of ginger ale commercials. With his male nurse, his son, and the irrepressible Blue, Leary sets off for Toronto on one last adventure as he revisits the scenes of his glorious life as King of the Ice.

Preț: 96.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.46€ • 20.06$ • 15.52£

18.46€ • 20.06$ • 15.52£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385666015

ISBN-10: 0385666012

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

ISBN-10: 0385666012

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

Notă biografică

The author of ten novels, Paul Quarrington was also a musician (most recently in the band Porkbelly Futures), an award-winning screenwriter and filmmaker, and an acclaimed non-fiction writer.

Paul Quarrington's novel, Galveston, was nominated for the Scotiabank Giller Prize; King Leary won the CBC's 2008 Canada Reads competition and the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal; and Whale Music was awarded the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction. Recently, Porkbelly Futures' self-titled second CD has been released to widespread acclaim, and Paul Quarrington's short film adaptation of The Ravine, entitled Pavane, was featured in the Moving Stories Short Film Festival. Paul Quarrington's non-fiction writing includes books on some of his favourite pastimes, such as fishing, hockey, and music. A regular contributor of book reviews, travel columns, and journalism to Canada's national newspapers and magazines, he also taught writing at Humber College and the University of Toronto.

Paul Quarringon passed away in January 2010.

Paul Quarrington's novel, Galveston, was nominated for the Scotiabank Giller Prize; King Leary won the CBC's 2008 Canada Reads competition and the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal; and Whale Music was awarded the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction. Recently, Porkbelly Futures' self-titled second CD has been released to widespread acclaim, and Paul Quarrington's short film adaptation of The Ravine, entitled Pavane, was featured in the Moving Stories Short Film Festival. Paul Quarrington's non-fiction writing includes books on some of his favourite pastimes, such as fishing, hockey, and music. A regular contributor of book reviews, travel columns, and journalism to Canada's national newspapers and magazines, he also taught writing at Humber College and the University of Toronto.

Paul Quarringon passed away in January 2010.

Extras

A sad tale’s best for winter.

I have one of sprites and goblins.

— A Winter’s Tale

Chapter Two

I was born and raised in Ottawa, Ontario — Bytown, as we say. The Ottawa Canal was practically in our backyard, and the reason I say practically is that we didn’t really have a backyard. There was this little square thing that was full of bricks, because my father was always planning to build something. I never did learn what the Jesus he meant to build, but he certainly had the bricks for it.

I thought the canal was a beautiful thing. I spent so much time beside the water that it seemed to the young me that the canal had moods. Sometimes it would be whitecapped and rough, and I wouldn’t think that the wind was up and blowing over a storm, I’d think the water was angry. Or sometimes it would be gentle, with little pieces of sunlight bouncing on it, and I knew that the canal was happy and that if I went swimming the water would play on my body.

But I loved her best when she froze.

A few nights of the right weather, and I’m talking thirty below, teethaching and nose-falling-off-type weather, and the canal would grow about a foot of ice. Hard as marble, and just as smooth. Strong and true. It gives me the goose bumps just thinking about it. Lookee there, see how goosebumped I am right now.

I can’t remember lacing on blades for the first time. Likewise with hockey. I’ve got no idea when I first heard of, saw, or played the game of hockey. Some years back, Clay Clinton and I were invited to one of those hockey schools for a seminar. It couldn’t have been that long back, come to think, because what we were discussing was something like The Development of Hockey in North America, which means we were trying to figure out a way of beating the Russians. So there was me there, and Clay (who was drunk much of the weekend, and occupied with the pursuit of somebody’s floozy wife), and this young coach from Minnesota.

And the lad from Minn. starts talking about the origins of hockey. He went on and on about soccer and lacrosse, English foot soldiers playing baggataway with the Indians, some Scandinavian entertainment called bandy. I bit my tongue, but the truth of the matter is, I never knew that hockey originated. I figured it was just always there, like the moon.

Now, there were three of us Leary lads, Francis, Lloyd, and myself, Percival. We all early on got reputations in our neighbourhood as good hockey players. Even though I was the youngest and the smallest, I was rated the best. Little Leary, they called me, a puff of Irish wind.

So one day — and this I remember like yesterday, better even, because what the hell happened yesterday other than Blue Hermann tweaking Mrs. Ames’s enormous bub, eliciting a shriek that popped my eardrums — this strange young lad shows up at the canal.

The strangest thing about him was the way he was dressed, namely, a full-length fur coat with a matching little cap. We just wore sweaters, one for every five degrees she dropped below freezing, and on this particular day I had on maybe six. This boy in the fur coat and matching cap stood by the snowbanks and watched us for almost half an hour, not saying a word. I was pretending to ignore the lad, but really I was studying him. He was fat, but

not the kind of fat that would get him called Fatty. Mostly what I noticed about him was his face, which was handsome as hell. The lad had gray eyes that seemed to have slivers of ice in them.

I decided to impress him, don’t ask me why. The next time I got the puck I danced down the canal like I was alone. Then I made like Cyclone Taylor. I still loved Taylor even though he had, the year previous, abandoned the Ottawa Senators for the loathsome Renfrew Millionaires. As you may know, Cyclone claimed that he could score a goal skating backwards, and he did this against the Senators, and that’s what I did myself, turning around and sailing past the pointmen, slapping the rubber with my heaviest backhand. The little boy standing between the two piles of snow that was the goal — who had been pretending to be Rat Westwick of the Silver Seven — just covered his head and let the puck fly by.

I have one of sprites and goblins.

— A Winter’s Tale

Chapter Two

I was born and raised in Ottawa, Ontario — Bytown, as we say. The Ottawa Canal was practically in our backyard, and the reason I say practically is that we didn’t really have a backyard. There was this little square thing that was full of bricks, because my father was always planning to build something. I never did learn what the Jesus he meant to build, but he certainly had the bricks for it.

I thought the canal was a beautiful thing. I spent so much time beside the water that it seemed to the young me that the canal had moods. Sometimes it would be whitecapped and rough, and I wouldn’t think that the wind was up and blowing over a storm, I’d think the water was angry. Or sometimes it would be gentle, with little pieces of sunlight bouncing on it, and I knew that the canal was happy and that if I went swimming the water would play on my body.

But I loved her best when she froze.

A few nights of the right weather, and I’m talking thirty below, teethaching and nose-falling-off-type weather, and the canal would grow about a foot of ice. Hard as marble, and just as smooth. Strong and true. It gives me the goose bumps just thinking about it. Lookee there, see how goosebumped I am right now.

I can’t remember lacing on blades for the first time. Likewise with hockey. I’ve got no idea when I first heard of, saw, or played the game of hockey. Some years back, Clay Clinton and I were invited to one of those hockey schools for a seminar. It couldn’t have been that long back, come to think, because what we were discussing was something like The Development of Hockey in North America, which means we were trying to figure out a way of beating the Russians. So there was me there, and Clay (who was drunk much of the weekend, and occupied with the pursuit of somebody’s floozy wife), and this young coach from Minnesota.

And the lad from Minn. starts talking about the origins of hockey. He went on and on about soccer and lacrosse, English foot soldiers playing baggataway with the Indians, some Scandinavian entertainment called bandy. I bit my tongue, but the truth of the matter is, I never knew that hockey originated. I figured it was just always there, like the moon.

Now, there were three of us Leary lads, Francis, Lloyd, and myself, Percival. We all early on got reputations in our neighbourhood as good hockey players. Even though I was the youngest and the smallest, I was rated the best. Little Leary, they called me, a puff of Irish wind.

So one day — and this I remember like yesterday, better even, because what the hell happened yesterday other than Blue Hermann tweaking Mrs. Ames’s enormous bub, eliciting a shriek that popped my eardrums — this strange young lad shows up at the canal.

The strangest thing about him was the way he was dressed, namely, a full-length fur coat with a matching little cap. We just wore sweaters, one for every five degrees she dropped below freezing, and on this particular day I had on maybe six. This boy in the fur coat and matching cap stood by the snowbanks and watched us for almost half an hour, not saying a word. I was pretending to ignore the lad, but really I was studying him. He was fat, but

not the kind of fat that would get him called Fatty. Mostly what I noticed about him was his face, which was handsome as hell. The lad had gray eyes that seemed to have slivers of ice in them.

I decided to impress him, don’t ask me why. The next time I got the puck I danced down the canal like I was alone. Then I made like Cyclone Taylor. I still loved Taylor even though he had, the year previous, abandoned the Ottawa Senators for the loathsome Renfrew Millionaires. As you may know, Cyclone claimed that he could score a goal skating backwards, and he did this against the Senators, and that’s what I did myself, turning around and sailing past the pointmen, slapping the rubber with my heaviest backhand. The little boy standing between the two piles of snow that was the goal — who had been pretending to be Rat Westwick of the Silver Seven — just covered his head and let the puck fly by.

Recenzii

“A type of literary hat trick...most engaging…. [Quarrington’s] colourful, inventive language is addictive.” The Globe and Mail

“An extraordinary writer with a rare gift.” Timothy Findley

“An extraordinary writer with a rare gift.” Timothy Findley