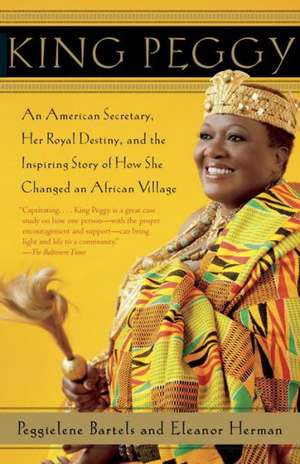

King Peggy: An American Secretary, Her Royal Destiny, and the Inspiring Story of How She Changed an African Village

Autor Peggielene Bartels, Eleanor Hermanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 feb 2013

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Books for a Better Life (2012)

King Peggy chronicles the astonishing journey of American secretary, Peggielene Bartels, who suddenly finds herself king to a town of 7,000 people on Ghana's central coast, half a world away. Upon arriving for her crowning ceremony in beautiful Otuam, she discovers the dire reality: there's no running water, no doctor, no high school, and many of the village elders are stealing the town's funds. To make matters worse, her uncle (the late king) sits in a morgue awaiting a proper funeral in the royal palace, which is in ruins. Peggy's first two years as king of Otuam unfold in a way that is stranger than fiction. In the end, a deeply traditional African town is uplifted by the ambitions of its decidedly modern female king, and Peggy is herself transformed, from an ordinary secretary to the heart and hope of her community.

Preț: 127.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 191

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.30€ • 25.44$ • 20.11£

24.30€ • 25.44$ • 20.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307742810

ISBN-10: 0307742814

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 8 PP. B&W/ MAP

Dimensiuni: 135 x 209 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307742814

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 8 PP. B&W/ MAP

Dimensiuni: 135 x 209 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Anchor Books

Extras

Excerpted from KING PEGGY: An American Secretary, Her Royal Destiny, and the Inspiring Story of How She Changed an African Village by Peggielene Bartels and Eleanor Herman Copyright © 2012 by Peggielene Bartels and Eleanor Herman. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When the council meeting ended at six, the sun was just rising and the world outside was silver. The elders returned to their fields to do some work before the day became too hot. Peggy went to her room to rest a bit and saw a line of children with heavy metal buckets of water on their heads trudging down the path from the bore hole behind the house. Some of them were headed for her kitchen.

Auntie Esi stood next to Peggy as she gazed out the window. “How far do they walk?” Peggy asked.

“There are only two bore holes, so the kids that live furthest away have to walk about a half hour in each direction.”

“An hour for a single bucket,” Peggy said quietly.

“And some kids make two or three trips before and after school. Some walk for six hours a day.”

“Is the water clean at least?”

Auntie Esi shrugged. “It’s not clean if you haul it from the pond. That water is a yellowish-brown, and that’s what the entire town had to use when the pipes first broke in 1977. But the local government representatives built two bore holes shortly after that which provide very clean water, though it costs money. A few pennies a bucket.”

Peggy scowled. “You mean they charge for clean water?”

Auntie Esi nodded. “The pumps break down a lot, so they use the money to pay for repairs.”

“And the people who can’t afford the bore hole water drink the yellowish-brown water?”

Auntie Esi nodded again. “They don’t get sick from it, though. For hundreds of years before the British brought piped water, people in Otuam got all their water from the pond. Many believe the goddess of the pond purifies the water and keeps them healthy.”

Peggy sighed, a deep sigh that came from the soul and rumbled through her entire body. Evidently the pond contained one of the seventy-seven gods and goddesses known to protect Otuam. But even so, no American king could allow her people to drink that disgusting water. And besides, it was well known that sometimes nature gods and goddesses left their ancient spots without a word of warning. If the goddess left, those drinking the water would sicken and even die. She would have to get those kids more bore holes, free bore holes, and eventually fix the pipes. How on earth was she going to afford it?

Auntie Esi put her weathered hand on Peggy’s shoulder. “You will fix the water later,” she said. “Remember the sparrow, who builds her nest one twig at a time. We are going to eat breakfast now, and after that we are going to give you your first royal etiquette lesson. You don’t want to disgrace the stool by doing something inappropriate for a Ghanaian king.” After breakfast, the aunties taught Peggy how to walk majestically. A king, they said, was never to show any hurry. The whole world waited for a king. Flapping around here and there like a chicken was undignified.

Auntie Esi strolled at a glacial pace down the hall, head up, shoulders back. “Like this, Nana. You bounce around too much and go too fast.”

“In the US, if I walked that slowly I would be hit by a car,” Peggy pointed out. “No one there would wait for me to cross the street. They would run me down, and as I bounced on the asphalt they would keep on going so they wouldn’t be late for a meeting.”

Auntie Esi smiled. “But there are very few cars in Otuam, and here they wouldn’t run over their king. Try it again, slowly.”

Peggy sighed. Give just a hint of a smile, they said, showing regal serenity. Shoulders relaxed. Head held high. Chin up. Slow, straight, determined steps. Self-consciously, she walked back and forth in front of them, like an awkward aspiring model training for the runway.

“Too fast!” cried one.

“Hold your chin higher!” said another.

“You’re frowning!” said Auntie Esi. “Don’t frown in public.”

“Don’t frown?” Peggy asked. “What if I see something I don’t like?”

“Don’t frown!” Auntie Esi repeated. “You can make a mental note of the problem and deal with it later.”

“Oh.”

“And you can’t eat or drink in public. It’s unseemly for a king to be shoving things into her face. Plus, if there is a witch in the crowd watching you she can make you choke to death on whatever you’re consuming.”

Peggy had heard about the no-eating-in-public rule, though she was unaware it had to do with witches. It made sense, though, that witches, known as vengeful, jealous creatures, would want to harm a king, especially one who stood for the good. Witches created havoc for the sheer malicious pleasure of it, and you never knew who in your village was a witch. Sudden illnesses, childhood deaths, accidents: they might all be traced back to the kindly old grandmother next door or the jovial uncle down the street. Only a traditional priest, using tried and true rituals, could determine if bad luck was caused by the ancestors punishing selfish behavior or by a witch making trouble for good people, and then prescribe the proper rituals to take care of it.

Peggy sighed again. As king, she had to worry whether Uncle Joseph would haunt her for not burying him in a timely manner. She had to remain vigilant against evil spirits who might zoom into her. And now she had to defend herself against spiteful jealous witches who could be anywhere. Not eating or drinking in public was simple compared to these more troubling issues.

“In Otuam I will abide by this rule,” she said. “But in the US, we all work so much that we have to grab a bite in public sometimes because when we get home it is too late to cook. And no one there knows I am a king.”

“They know at the embassy. One of them might be a witch. And even if they aren’t, it would be undignified to stuff your face even there.”

Witches. At the embassy. Looking back on her twenty-nine years there, Peggy realized this could explain a lot of things.

“And Nana,” Auntie Esi said, “the king can’t argue in public.”

“Argue in public?” she said, all wide-eyed innocence. Surely they hadn’t heard anything of her arguments at the embassy. “Me?’

Cousin Comfort chimed in, “Nana, we all know that even since you were a small child, when someone misbehaves, you can’t let it go.”

“When you see an injustice,” Cousin Comfort continued, “you are like a village dog with his jaws locked on a bone. You just don’t give it up. But as king you will have to deal with these things in the council chamber, and not yell at people on the street or beat them with brooms.” The aunties all laughed at that one.

Auntie Esi said, “And if you are wearing the crown and want to say a crude thing, you have to take it off before you speak so as not to dishonor it.”

“And there’s one more thing,” Auntie Esi added. “It is not regal for a king to always be running off to the bathroom. When you have official events, we will give you a special dish that takes away the urge to urinate for the entire day. Still, it is best not to drink much before or during. Just a little water so you don’t faint in the heat.”

The heat. Though it was still early, the delicious coolness of the night had vanished, replaced by a stultifying miasma of sticky air. During the etiquette lesson, Peggy and her aunties had glowed at first, then perspired, and now the sweat was running down their faces in rivulets.

Peggy knew that the best drink to stave off the heat was beer, which Ghanaians drank in the morning as the heat rose. But beer was also the very drink to make you most want to run to the toilet. Peggy remembered an American comedian who once said, It’s good to be da king. Except in Otuam the king would have to be thirsty, and hot, with a bursting bladder and witches putting hexes on her. Maybe it wasn’t always good to be the king of Otuam.

“And another thing,” Auntie Esi said, “As an American, you probably brought deodorant. But here people cut a lemon in half and rub the two halves all over their bodies. They let the lemon juice sink in, and a while later they bathe with soap and water. This works better than deodorant.” For lunch they had the staple food of Otuam ߝ fresh fish deep fried, on white rice, and covered with a spicy onion and tomato sauce. They would be eating it for lunch and dinner for Peggy’s entire stay. In the US she often didn’t think twice about the wide range of food she had and would have complained if she had to eat the same thing all day long. Africans could enjoy the same meal again and again and be grateful for it.

“By God’s grace, the people here are never hungry,” Auntie Esi explained as they dove into their meal. “They are very poor, and don’t possess much, and they have to haul water. But there is plenty of food. Nana, you should see the dozens of fishing canoes that come in every morning, their nets heavy with fish. And the farms produce beautiful pineapples, papayas, coconuts, plantains, and cassavas.”

That was indeed a blessing. While the other problems were vexing, hunger among Peggy’s people would have devastated her. The people of Otuam would never be hungry, and living in Ghana they would certainly never be cold.

When the council meeting ended at six, the sun was just rising and the world outside was silver. The elders returned to their fields to do some work before the day became too hot. Peggy went to her room to rest a bit and saw a line of children with heavy metal buckets of water on their heads trudging down the path from the bore hole behind the house. Some of them were headed for her kitchen.

Auntie Esi stood next to Peggy as she gazed out the window. “How far do they walk?” Peggy asked.

“There are only two bore holes, so the kids that live furthest away have to walk about a half hour in each direction.”

“An hour for a single bucket,” Peggy said quietly.

“And some kids make two or three trips before and after school. Some walk for six hours a day.”

“Is the water clean at least?”

Auntie Esi shrugged. “It’s not clean if you haul it from the pond. That water is a yellowish-brown, and that’s what the entire town had to use when the pipes first broke in 1977. But the local government representatives built two bore holes shortly after that which provide very clean water, though it costs money. A few pennies a bucket.”

Peggy scowled. “You mean they charge for clean water?”

Auntie Esi nodded. “The pumps break down a lot, so they use the money to pay for repairs.”

“And the people who can’t afford the bore hole water drink the yellowish-brown water?”

Auntie Esi nodded again. “They don’t get sick from it, though. For hundreds of years before the British brought piped water, people in Otuam got all their water from the pond. Many believe the goddess of the pond purifies the water and keeps them healthy.”

Peggy sighed, a deep sigh that came from the soul and rumbled through her entire body. Evidently the pond contained one of the seventy-seven gods and goddesses known to protect Otuam. But even so, no American king could allow her people to drink that disgusting water. And besides, it was well known that sometimes nature gods and goddesses left their ancient spots without a word of warning. If the goddess left, those drinking the water would sicken and even die. She would have to get those kids more bore holes, free bore holes, and eventually fix the pipes. How on earth was she going to afford it?

Auntie Esi put her weathered hand on Peggy’s shoulder. “You will fix the water later,” she said. “Remember the sparrow, who builds her nest one twig at a time. We are going to eat breakfast now, and after that we are going to give you your first royal etiquette lesson. You don’t want to disgrace the stool by doing something inappropriate for a Ghanaian king.” After breakfast, the aunties taught Peggy how to walk majestically. A king, they said, was never to show any hurry. The whole world waited for a king. Flapping around here and there like a chicken was undignified.

Auntie Esi strolled at a glacial pace down the hall, head up, shoulders back. “Like this, Nana. You bounce around too much and go too fast.”

“In the US, if I walked that slowly I would be hit by a car,” Peggy pointed out. “No one there would wait for me to cross the street. They would run me down, and as I bounced on the asphalt they would keep on going so they wouldn’t be late for a meeting.”

Auntie Esi smiled. “But there are very few cars in Otuam, and here they wouldn’t run over their king. Try it again, slowly.”

Peggy sighed. Give just a hint of a smile, they said, showing regal serenity. Shoulders relaxed. Head held high. Chin up. Slow, straight, determined steps. Self-consciously, she walked back and forth in front of them, like an awkward aspiring model training for the runway.

“Too fast!” cried one.

“Hold your chin higher!” said another.

“You’re frowning!” said Auntie Esi. “Don’t frown in public.”

“Don’t frown?” Peggy asked. “What if I see something I don’t like?”

“Don’t frown!” Auntie Esi repeated. “You can make a mental note of the problem and deal with it later.”

“Oh.”

“And you can’t eat or drink in public. It’s unseemly for a king to be shoving things into her face. Plus, if there is a witch in the crowd watching you she can make you choke to death on whatever you’re consuming.”

Peggy had heard about the no-eating-in-public rule, though she was unaware it had to do with witches. It made sense, though, that witches, known as vengeful, jealous creatures, would want to harm a king, especially one who stood for the good. Witches created havoc for the sheer malicious pleasure of it, and you never knew who in your village was a witch. Sudden illnesses, childhood deaths, accidents: they might all be traced back to the kindly old grandmother next door or the jovial uncle down the street. Only a traditional priest, using tried and true rituals, could determine if bad luck was caused by the ancestors punishing selfish behavior or by a witch making trouble for good people, and then prescribe the proper rituals to take care of it.

Peggy sighed again. As king, she had to worry whether Uncle Joseph would haunt her for not burying him in a timely manner. She had to remain vigilant against evil spirits who might zoom into her. And now she had to defend herself against spiteful jealous witches who could be anywhere. Not eating or drinking in public was simple compared to these more troubling issues.

“In Otuam I will abide by this rule,” she said. “But in the US, we all work so much that we have to grab a bite in public sometimes because when we get home it is too late to cook. And no one there knows I am a king.”

“They know at the embassy. One of them might be a witch. And even if they aren’t, it would be undignified to stuff your face even there.”

Witches. At the embassy. Looking back on her twenty-nine years there, Peggy realized this could explain a lot of things.

“And Nana,” Auntie Esi said, “the king can’t argue in public.”

“Argue in public?” she said, all wide-eyed innocence. Surely they hadn’t heard anything of her arguments at the embassy. “Me?’

Cousin Comfort chimed in, “Nana, we all know that even since you were a small child, when someone misbehaves, you can’t let it go.”

“When you see an injustice,” Cousin Comfort continued, “you are like a village dog with his jaws locked on a bone. You just don’t give it up. But as king you will have to deal with these things in the council chamber, and not yell at people on the street or beat them with brooms.” The aunties all laughed at that one.

Auntie Esi said, “And if you are wearing the crown and want to say a crude thing, you have to take it off before you speak so as not to dishonor it.”

“And there’s one more thing,” Auntie Esi added. “It is not regal for a king to always be running off to the bathroom. When you have official events, we will give you a special dish that takes away the urge to urinate for the entire day. Still, it is best not to drink much before or during. Just a little water so you don’t faint in the heat.”

The heat. Though it was still early, the delicious coolness of the night had vanished, replaced by a stultifying miasma of sticky air. During the etiquette lesson, Peggy and her aunties had glowed at first, then perspired, and now the sweat was running down their faces in rivulets.

Peggy knew that the best drink to stave off the heat was beer, which Ghanaians drank in the morning as the heat rose. But beer was also the very drink to make you most want to run to the toilet. Peggy remembered an American comedian who once said, It’s good to be da king. Except in Otuam the king would have to be thirsty, and hot, with a bursting bladder and witches putting hexes on her. Maybe it wasn’t always good to be the king of Otuam.

“And another thing,” Auntie Esi said, “As an American, you probably brought deodorant. But here people cut a lemon in half and rub the two halves all over their bodies. They let the lemon juice sink in, and a while later they bathe with soap and water. This works better than deodorant.” For lunch they had the staple food of Otuam ߝ fresh fish deep fried, on white rice, and covered with a spicy onion and tomato sauce. They would be eating it for lunch and dinner for Peggy’s entire stay. In the US she often didn’t think twice about the wide range of food she had and would have complained if she had to eat the same thing all day long. Africans could enjoy the same meal again and again and be grateful for it.

“By God’s grace, the people here are never hungry,” Auntie Esi explained as they dove into their meal. “They are very poor, and don’t possess much, and they have to haul water. But there is plenty of food. Nana, you should see the dozens of fishing canoes that come in every morning, their nets heavy with fish. And the farms produce beautiful pineapples, papayas, coconuts, plantains, and cassavas.”

That was indeed a blessing. While the other problems were vexing, hunger among Peggy’s people would have devastated her. The people of Otuam would never be hungry, and living in Ghana they would certainly never be cold.

Notă biografică

Peggielene Bartels was born in Ghana in 1953 and moved to Washington, DC, in her early twenties to work at Ghana’s embassy. She became an American in 1997. In 2008, she was chosen to be king of Otuam, a Ghanaian village of 7,000 people.

Eleanor Herman is the author of three books of women’s history, including The New York Times bestseller Sex with Kings. Her profile of Peggy was a cover story for The Washington Post Magazine.

Eleanor Herman is the author of three books of women’s history, including The New York Times bestseller Sex with Kings. Her profile of Peggy was a cover story for The Washington Post Magazine.

Recenzii

Praise for Peggielene Bartels and Eleanor Herman's King Peggy

2012 Finalist for the Books for a Better Life Award

A 2013 Amelia Bloomer List Selection

“Captivating. . . . King Peggy is a great case study on how one person—with the proper encouragement and support—can bring light and life to a community. . . . Extremely well-written and amusing. . . . Candid and humble. . . . A captivating glimpse into the mental and spiritual transformation of a middle-aged African American woman as she steps into her royal destiny as an African king.”

—The Baltimore Times

“An astonishing and wonderful book about a real-life Mma Ramotswe. An utter joy.”

—Alexander McCall Smith, author of the No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency series

“A wondrous tale of how a woman rose to great heights in circumstances one would never dream of, in a place which most of us cannot imagine living. Compelling and heartwarming, [King Peggy] is a most enjoyable and absorbing read.”

—Deborah Rodriguez, author of Kabul Beauty School

“This irresistible real-life Cinderella story is entertaining, inspiring, and informative.”

—Tucson Citizen

“There’s an unlikely new leader in West Africa. . . . Bartels had to quickly and forcefully let tribal elders know that despite being far away and female, she had every intention of taking her position seriously—and being taken seriously in turn.”

—NPR

“King Peggy is wildly entertaining and thoroughly engaging, and Peggy is a true modern hero as she battles her council of elders who try to maintain their old lifestyles of privilege and greed. King Peggy reminds readers that the truth is often stranger than fiction; King Peggy herself does not disappoint, neither as a ruler nor a storyteller.”

—Shelf Awareness

“In the moving story of Peggielene Bartels, all of us can feel a connection to our ancestors, and a reminder of the good that can come from courageously embracing unexpected responsibilities.”

—Jeffrey Zaslow, author of The Girls from Ames and coauthor of The Last Lecture

“Though it sounds the stuff of fairytale and legend, King Peggy is the fascinating true story of her courageous acceptance of this difficult role and her unyielding resolve to help the people of Otuam. . . . Full of pathos, humor and insight into a world where poverty mingles with hope and happiness, King Peggy is an inspiration and proof positive that when it comes to challenging roles for women, ‘We Can Do It!’”

—BookPage

“[A] winning tale of epic proportions, full of intrigue, royal court plotting, cases of mistaken identity and whispered words from beyond the grave. Upon arrival, King Peggy—who left Ghana three decades earlier and has since become an American citizen—found an uphill battle and vowed to tackle the issues plaguing her community: domestic violence, poverty and lack of access to clean water, health care and education. . . . Florid description of the landscape, culture and characters work together to fully evoke the rhythms of African life. Ultimately, readers come away with not only a sense of how King Peggy was able to transform Otuam, but also an understanding of how the town and its inhabitants transformed her.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“King Peggy is the funny, wide-eyed account of [Peggielene Bartel’s] struggle to overcome sexism, systemic corruption and poverty without losing her will to lead or the love of her 7,000 subjects. . . . Co-author Herman says her interest in Africa came from the fiction of Alexander McCall Smith; she thinks she has met in Peggy a real-life Mma Ramotswe, and readers will quickly agree.”

—Maclean’s (Toronto)

2012 Finalist for the Books for a Better Life Award

A 2013 Amelia Bloomer List Selection

“Captivating. . . . King Peggy is a great case study on how one person—with the proper encouragement and support—can bring light and life to a community. . . . Extremely well-written and amusing. . . . Candid and humble. . . . A captivating glimpse into the mental and spiritual transformation of a middle-aged African American woman as she steps into her royal destiny as an African king.”

—The Baltimore Times

“An astonishing and wonderful book about a real-life Mma Ramotswe. An utter joy.”

—Alexander McCall Smith, author of the No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency series

“A wondrous tale of how a woman rose to great heights in circumstances one would never dream of, in a place which most of us cannot imagine living. Compelling and heartwarming, [King Peggy] is a most enjoyable and absorbing read.”

—Deborah Rodriguez, author of Kabul Beauty School

“This irresistible real-life Cinderella story is entertaining, inspiring, and informative.”

—Tucson Citizen

“There’s an unlikely new leader in West Africa. . . . Bartels had to quickly and forcefully let tribal elders know that despite being far away and female, she had every intention of taking her position seriously—and being taken seriously in turn.”

—NPR

“King Peggy is wildly entertaining and thoroughly engaging, and Peggy is a true modern hero as she battles her council of elders who try to maintain their old lifestyles of privilege and greed. King Peggy reminds readers that the truth is often stranger than fiction; King Peggy herself does not disappoint, neither as a ruler nor a storyteller.”

—Shelf Awareness

“In the moving story of Peggielene Bartels, all of us can feel a connection to our ancestors, and a reminder of the good that can come from courageously embracing unexpected responsibilities.”

—Jeffrey Zaslow, author of The Girls from Ames and coauthor of The Last Lecture

“Though it sounds the stuff of fairytale and legend, King Peggy is the fascinating true story of her courageous acceptance of this difficult role and her unyielding resolve to help the people of Otuam. . . . Full of pathos, humor and insight into a world where poverty mingles with hope and happiness, King Peggy is an inspiration and proof positive that when it comes to challenging roles for women, ‘We Can Do It!’”

—BookPage

“[A] winning tale of epic proportions, full of intrigue, royal court plotting, cases of mistaken identity and whispered words from beyond the grave. Upon arrival, King Peggy—who left Ghana three decades earlier and has since become an American citizen—found an uphill battle and vowed to tackle the issues plaguing her community: domestic violence, poverty and lack of access to clean water, health care and education. . . . Florid description of the landscape, culture and characters work together to fully evoke the rhythms of African life. Ultimately, readers come away with not only a sense of how King Peggy was able to transform Otuam, but also an understanding of how the town and its inhabitants transformed her.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“King Peggy is the funny, wide-eyed account of [Peggielene Bartel’s] struggle to overcome sexism, systemic corruption and poverty without losing her will to lead or the love of her 7,000 subjects. . . . Co-author Herman says her interest in Africa came from the fiction of Alexander McCall Smith; she thinks she has met in Peggy a real-life Mma Ramotswe, and readers will quickly agree.”

—Maclean’s (Toronto)

Premii

- Books for a Better Life Finalist, 2012