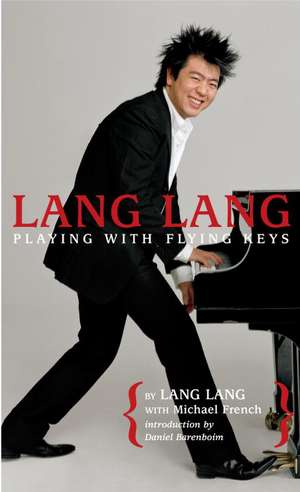

Lang Lang

Autor Lang Langen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 ian 2010 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 44.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 66

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.47€ • 8.75$ • 7.05£

8.47€ • 8.75$ • 7.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Livrare express 18-22 februarie pentru 15.57 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440422846

ISBN-10: 0440422841

Pagini: 215

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations, colour illustrations, maps

Dimensiuni: 107 x 177 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Laurel Leaf Library

ISBN-10: 0440422841

Pagini: 215

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations, colour illustrations, maps

Dimensiuni: 107 x 177 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Laurel Leaf Library

Notă biografică

Lang Lang is a renowned classical pianist who has performed with major orchestras all over the world. Although he is on tour most of the time, he has homes in Philadelphia, China, and Berlin.

Michael French has adapted Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley and Ron Powers, and is the author of more than 20 books. He lives in Santa Barbara, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

From the Hardcover edition.

Michael French has adapted Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley and Ron Powers, and is the author of more than 20 books. He lives in Santa Barbara, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

I have many early childhood memories. Like strands in a tapestry, they weave a mixed impression--joy, hardship, hope, sadness, struggle, and success. Some strands stand out in vivid detail.

When I was two years old, a simple barracks apartment on the Shenyang air force base was our home. My father, a thin man of average height, was the silent type. In fact, he was stern and I have no memory of him smiling. He played professionally in the air force orchestra. We had very few luxuries, but they included an upright piano purchased by my parents when my father grew convinced I had a special gift for music. My mother later told me I could read musical notes before I learned the alphabet, and with my unusually large hands and long fingers, I loved gliding my fingertips on the keys. Of course, I couldn't touch the pedals. In fact, I could only touch the keys by placing pillows on my piano bench. But my father said I was creating music, that I knew intuitively when the notes harmonized. Most important to me, I was filling my ear with beautiful sounds that in turn filled my imagination with incredible stories I made up as I played for hours at a time.

In the air force orchestra my father played the erhu--a popular folk instrument with two strings, a cross between a violin and a small bass--but he told my mother from the beginning that I should be taught the piano.

"The piano is the most beloved instrument in the world," he declared, and she agreed. My father, whose name is Lang Guoren, was my first teacher.

***

Zhou Xiulan also loved music. My mother had grown up listening to Peking opera on the radio with her parents, and when she was a teenager, she developed a lyrical voice. She dreamed of singing in a concert. But as it did to my father, the Cultural Revolution started in the 1960s. My parents' families were either property owners or intellectuals, and middle-class. My parents and their families moved from their homes in the city to distant rice farms, where they worked long hours. My parents lived in the countryside for five years. They did not know each other at that time.

When he was twenty-five years old, before he was married to my mother, my father applied for admission to the Shenyang Conservatory of Music. He was now back home and determined to forge a career for himself. His talent and dedication to the erhu were extraordinary, and among all the applicants that year he placed first on two entrance exams. But at the last moment, on a trumped-up technicality, he was denied admission.

I don't think his soul ever quite healed. I didn't understand any of this until I was older, but almost from the beginning, I felt his frustration and his high expectations for me.

"Practice, Lang Lang. Practice day and night. Do not dream of anything but being the best pianist you can be," he would say to me over and over.

My mother told him he was too strict, and sometimes he was, but his will almost always prevailed. "Don't pamper our son," he declared if he caught my mother reading me a story with my head against her shoulder. "He should be playing the piano, not listening to silly tales. He has a gift, but it means nothing without hard work. You're only spoiling him."

"He's just a little boy," she countered. "All boys need time to play and dream."

"He has his dream. Now go, Lang Lang, and play your lessons until it is time for supper."

I dreamed often the dream my father had for me, to become a great pianist. While I sometimes watched cartoons on a neighbor's television, played with other children on the air force base, and created my own fantasies around the stories my mother read to me, most of my time was occupied by the piano. I knew of other children in Shenyang who practiced long hours. They too dreamed of one day being admitted to the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. I had to play longer and better than my competition. My father and I would have it no other way.

By the time I started school at age seven, Lang Guoren had fashioned an unyielding schedule for me:

5:45 a.m.: Get up and practice piano for an hour.

7:00 a.m.: Go to school.

Noon: Come home for a fifteen-minute lunch, then forty-five minutes of piano.

After school: Two hours of practice before dinner and a chance to watch some cartoon shows.

After dinner: Two more hours of practice, then homework.

When I finished any homework and crawled into bed, it was late at night.

On occasion, when my father wasn't around, I would take a break from the piano and hang around my mother, helping her in the kitchen or listen to her wonderful stories. I knew how much she loved me by the way she doted on my smile and never tired of my tireless questions.

I wanted to know everything about my mother's and father's families and how my parents had met and fallen in love. At first her father had not approved of Lang Guoren because he failed to win admission to the conservatory and he had no job prospects. But my father was persistent in all things, and when he was selected for the air force orchestra, my grandfather finally accepted his daughter's stubborn young suitor into the family.

My parents were married in April 1980, and a little more than two years later, on June 14, 1982, I came into this world by the skin of my teeth. My mother told me that the umbilical cord was wrapped so tightly around my neck that my face was green. The doctor had to work quickly.

"You mean I almost died," I answered, terrified by the thought, whenever she told this story.

"No, my child. You didn't die because you had work to do. You had music to bring into the world."

I would be my parents' first and only child, because in order to preserve its resources for a swelling population, the government began a one-child-per-family policy only in the city. This meant both my parents lavished an incredible amount of attention on me. While my mother's natural inclination was to nurture and indulge me, my father expected near perfection from his piano prodigy. After I turned three, every night he asked how many hours I had practiced that day. If my answer didn't please him, I would abandon whatever I was doing and go back to the piano. It was as if he thought a clock alone could determine my future. Because of the one-child policy, many children born in the 1980s were pushed and pressured by their parents. My experience of being pressed to the limit by my father was not the exception. Parents who had not achieved their own dreams put all their unrealized hopes onto their one and only child. This was especially true for future musicians, but it applied in the areas of sports and science as well.

What he didn't understand, and I was too young to explain, was the relationship between watching television or having my mother read to me and becoming a great pianist.

From the Hardcover edition.

When I was two years old, a simple barracks apartment on the Shenyang air force base was our home. My father, a thin man of average height, was the silent type. In fact, he was stern and I have no memory of him smiling. He played professionally in the air force orchestra. We had very few luxuries, but they included an upright piano purchased by my parents when my father grew convinced I had a special gift for music. My mother later told me I could read musical notes before I learned the alphabet, and with my unusually large hands and long fingers, I loved gliding my fingertips on the keys. Of course, I couldn't touch the pedals. In fact, I could only touch the keys by placing pillows on my piano bench. But my father said I was creating music, that I knew intuitively when the notes harmonized. Most important to me, I was filling my ear with beautiful sounds that in turn filled my imagination with incredible stories I made up as I played for hours at a time.

In the air force orchestra my father played the erhu--a popular folk instrument with two strings, a cross between a violin and a small bass--but he told my mother from the beginning that I should be taught the piano.

"The piano is the most beloved instrument in the world," he declared, and she agreed. My father, whose name is Lang Guoren, was my first teacher.

***

Zhou Xiulan also loved music. My mother had grown up listening to Peking opera on the radio with her parents, and when she was a teenager, she developed a lyrical voice. She dreamed of singing in a concert. But as it did to my father, the Cultural Revolution started in the 1960s. My parents' families were either property owners or intellectuals, and middle-class. My parents and their families moved from their homes in the city to distant rice farms, where they worked long hours. My parents lived in the countryside for five years. They did not know each other at that time.

When he was twenty-five years old, before he was married to my mother, my father applied for admission to the Shenyang Conservatory of Music. He was now back home and determined to forge a career for himself. His talent and dedication to the erhu were extraordinary, and among all the applicants that year he placed first on two entrance exams. But at the last moment, on a trumped-up technicality, he was denied admission.

I don't think his soul ever quite healed. I didn't understand any of this until I was older, but almost from the beginning, I felt his frustration and his high expectations for me.

"Practice, Lang Lang. Practice day and night. Do not dream of anything but being the best pianist you can be," he would say to me over and over.

My mother told him he was too strict, and sometimes he was, but his will almost always prevailed. "Don't pamper our son," he declared if he caught my mother reading me a story with my head against her shoulder. "He should be playing the piano, not listening to silly tales. He has a gift, but it means nothing without hard work. You're only spoiling him."

"He's just a little boy," she countered. "All boys need time to play and dream."

"He has his dream. Now go, Lang Lang, and play your lessons until it is time for supper."

I dreamed often the dream my father had for me, to become a great pianist. While I sometimes watched cartoons on a neighbor's television, played with other children on the air force base, and created my own fantasies around the stories my mother read to me, most of my time was occupied by the piano. I knew of other children in Shenyang who practiced long hours. They too dreamed of one day being admitted to the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. I had to play longer and better than my competition. My father and I would have it no other way.

By the time I started school at age seven, Lang Guoren had fashioned an unyielding schedule for me:

5:45 a.m.: Get up and practice piano for an hour.

7:00 a.m.: Go to school.

Noon: Come home for a fifteen-minute lunch, then forty-five minutes of piano.

After school: Two hours of practice before dinner and a chance to watch some cartoon shows.

After dinner: Two more hours of practice, then homework.

When I finished any homework and crawled into bed, it was late at night.

On occasion, when my father wasn't around, I would take a break from the piano and hang around my mother, helping her in the kitchen or listen to her wonderful stories. I knew how much she loved me by the way she doted on my smile and never tired of my tireless questions.

I wanted to know everything about my mother's and father's families and how my parents had met and fallen in love. At first her father had not approved of Lang Guoren because he failed to win admission to the conservatory and he had no job prospects. But my father was persistent in all things, and when he was selected for the air force orchestra, my grandfather finally accepted his daughter's stubborn young suitor into the family.

My parents were married in April 1980, and a little more than two years later, on June 14, 1982, I came into this world by the skin of my teeth. My mother told me that the umbilical cord was wrapped so tightly around my neck that my face was green. The doctor had to work quickly.

"You mean I almost died," I answered, terrified by the thought, whenever she told this story.

"No, my child. You didn't die because you had work to do. You had music to bring into the world."

I would be my parents' first and only child, because in order to preserve its resources for a swelling population, the government began a one-child-per-family policy only in the city. This meant both my parents lavished an incredible amount of attention on me. While my mother's natural inclination was to nurture and indulge me, my father expected near perfection from his piano prodigy. After I turned three, every night he asked how many hours I had practiced that day. If my answer didn't please him, I would abandon whatever I was doing and go back to the piano. It was as if he thought a clock alone could determine my future. Because of the one-child policy, many children born in the 1980s were pushed and pressured by their parents. My experience of being pressed to the limit by my father was not the exception. Parents who had not achieved their own dreams put all their unrealized hopes onto their one and only child. This was especially true for future musicians, but it applied in the areas of sports and science as well.

What he didn't understand, and I was too young to explain, was the relationship between watching television or having my mother read to me and becoming a great pianist.

From the Hardcover edition.