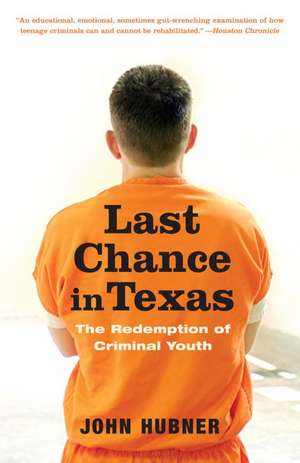

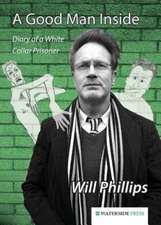

Last Chance in Texas: The Redemption of Criminal Youth

Autor John Hubneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2008

While reporting on the juvenile court system, journalist John Hubner kept hearing about a facility in Texas that ran the most aggressive–and one of the most successful–treatment programs for violent young offenders in America. How was it possible, he wondered, that a state like Texas, famed for its hardcore attitude toward crime and punishment, could be leading the way in the rehabilitation of violent and troubled youth?

Now Hubner shares the surprising answers he found over months of unprecedented access to the Giddings State School, home to “the worst of the worst”: four hundred teenage lawbreakers convicted of crimes ranging from aggravated assault to murder. Hubner follows two of these youths–a boy and a girl–through harrowing group therapy sessions in which they, along with their fellow inmates, recount their crimes and the abuse they suffered as children. The key moment comes when the young offenders reenact these soul-shattering moments with other group members in cathartic outpourings of suffering and anger that lead, incredibly, to genuine remorse and the beginnings of true empathy . . . the first steps on the long road to redemption.

Cutting through the political platitudes surrounding the controversial issue of juvenile justice, Hubner lays bare the complex ties between abuse and violence. By turns wrenching and uplifting, Last Chance in Texas tells a profoundly moving story about the children who grow up to inflict on others the violence that they themselves have suffered. It is a story of horror and heartbreak, yet ultimately full of hope.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 116.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.31€ • 24.24$ • 18.75£

22.31€ • 24.24$ • 18.75£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 21 aprilie-05 mai

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375759987

ISBN-10: 0375759980

Pagini: 277

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375759980

Pagini: 277

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

John Hubner is a former staff writer at the Boston Phoenix. He was also a magazine writer and investigative reporter for many years at the San Jose Mercury News, where he is now the regional editor. He lives with his wife and two children in Santa Cruz.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1.

“LOOKING LIKE PSYCHOPATHS”

“Tell us what you know about Capital Offenders,” Kelley asks the group.

Up until this moment, the boys’ reactions have been as uniform as their haircuts and clothing. Heads nodded when a yes was required, went sideways when the answer was no. Now, the masks are coming off. The youth with one eye breaks into a slow grin. A boy with peaked features and startling blue eyes in the second row waves his hand in the air. He looks up, surprised to see it there.

“Life Stories, miss. We’ll be telling our Life Stories,” says a small, somber black youth with large eyes. He inflects the words “Life Stories” in a way that makes it plain they are uppercase. Those two words are al- ways capitalized in the TYC resocialization dialect these young men have learned to speak.

“You can’t leave anything out! You go over it and over it until it’s all out there in the open,’’ adds a youth with a solid-gold front tooth, the symbol of a successful drug dealer.

“You can’t be fronting. No way can you front your way through,” declares a powerfully built young man in the first row. He is wearing granny glasses and could pass for a scholar-athlete if his forearms and biceps weren’t so heavily gang-tattooed.

“You can’t front empathy,” agrees a slight, boyish Korean-American. “If it ain’t real, you got to get real. You can’t be hiding behind no thinking errors.”

“Life stories.” “Empathy.” “Thinking errors.” It turns out that human behavior and the programs designed to alter it are inextricably tied to language. The fact that the national debate over delinquency issues rarely, if ever, reaches a level where language is explored is one reason why the more lofty the setting—a mahogany-paneled legislative hearing room in a state capital; a Senate subcommittee room with chandeliers and marble floors in Washington, D.C.—the more ersatz the debate. Frontline treatment specialists in Giddings take little heed of congressional hearings such as “Is Treating Juvenile Offenders Cost-Effective?” The people who actually do the work tend to view splashy hearings as little more than a platform for grandstanding politicians, one-issue zealots, and academics pushing a thesis. On the front lines, that question has been settled: treatment works.

It is one thing to say that about programs in a state institution. Taxpayers are picking up the bills, and the outcomes, no matter how scientifically they are evaluated, remain suspect because state institutions collect their own data and measure their own results. It is quite another when the marketplace says that intense treatment changes the trajectory of troubled teenagers’ lives. The best evidence of that is the “emotional-growth boarding schools” that have sprung up west of the Rockies in the last twenty years at a rate that rivals the growth of traditional prep schools in New England in the nineteenth century. These schools cater to teenagers who are so deeply into drugs and self-destructive behavior, their parents are terrified they will not live to turn twenty. The tuition at CEDU, the oldest of the emotional-growth, or “therapeutic,” boarding schools (founded in 1967 in Palm Springs, California), is well over $100,000 a year. If the cost is astounding, so are the results. Families that can afford a six-figure annual tuition would not keep enrolling their children in CEDU if they did not see tremendous changes.

CEDU is at one end of the socioeconomic spectrum, Giddings is at the other. And yet the programs they operate are very similar. In both places, teenagers begin by memorizing a language they will eventually internalize. In both schools, the students come close to running the programs themselves.

The information the boys are practically shouting at Kelley did not come only from a manual or a lecture. Much of it came from their peers. They know so much about what is going to happen because after the eighteen boys were selected from the main Giddings population, they were transferred to Cottages 5-A and 5-B, where they moved in with a dozen students who had recently completed Capital Offenders. No introduction presented by a staff member, no matter how eloquent, carries the weight of a COG veteran who says, “Listen up, this is what they gonna have you do.’’

The eighteen boys in this room have spent the last two to four years immersed in the resocialization program that structures life in the State School. Resocialization is a rethinking of the oldest concept in juvenile justice—rehabilitation—and in some ways, the word is poorly chosen. It assumes that some early socialization occurred in the lives of these boys, and for a majority, that did not happen.

An average, functioning family acts as a crucible where children are socialized, i.e., civilized, meaning they learn to relate to others through the relationships they form with parents and siblings. Most of the boys in this room come from families where the adults were drunk, high, street criminals, or in prison. In their families, “socialization” too often meant getting together to shoot hard drugs.

Giddings is not an attempt to re-create the family. That never works, in institutions, group homes, or foster homes. Kids instinctively rebel—This is bullshit! You’re not my real dad! Instead, Giddings is a gigantic bell jar where 390 young offenders are under intense observation sixteen hours a day. Over the past few years, these boys have spent countless hours in one kind of a group or another, acquiring skills that were not ingrained in their families of origin.

“Thinking errors” are at the heart of this process. Along with clothing, one of the first things a youth receives upon arriving in a TYC institution is Changing Course: A Student Workbook for Resocialization. As soon as he gets his layout down, he is told to turn to Chapter Three and memorize the list of nine thinking errors. They are: deceiving, downplaying, avoiding, blaming, making excuses, jumping to conclusions, acting helpless, overreacting, and feeling special. All of us employ these techniques at one time or another. These kids have used them in a way that has harmed others, and will allow them to keep on harming others, if their thought processes are not confronted and altered.

“Thinking errors are used to justify criminal behavior,” says Linda Reyes. “The error is in the justification, not in the fact. A youth can state true facts: I was sexually abused. Therefore, I sexually abused my sister. The thinking error is not in the facts. It is in the justification based on the facts.”

Do all newly incarcerated young felons hate memorizing thinking errors? They certainly do. Do they do it by rote, as if they were memorizing words in a foreign language? Of course. Learning a new language is like picking up a tool chest. The real work is learning to use those tools— sitting in a group and stopping a peer in midsentence with, “Hold on, right there. You just used a thinking error. Can you name it?” and then helping him see he is “avoiding” or “downplaying.” This is an arduous practice, akin to a young musician learning the scales. It goes on and on and on, day after day. Walk into any cottage after dinner and the boys are likely to be sitting in a circle, conducting a behavior group. Typically, a boy has erupted in anger at a juvenile corrections officer—“Jay-Ko” in the Giddings vernacular—who ordered him to clean up his “PA,” or personal area, a small clothes closet that sits at the foot of every bed. Instead of referring the boy to the security unit for being disobedient, the Jay-Ko called a behavior group. The group may spend hours in the circle, trying to help the boy understand why he got angry, and how anger feeds into his offense cycle.

The boys entering Capital Offenders are about to become archaeologists of the self, slowly and methodically sifting through their own lives. Each youth will spend two to three three-and-a-half-hour sessions telling his life story. At first glance, this does not seem daunting. Most of us, in one way or another, are telling one another our life stories all the time. But for these boys, the task is terrifying. They have soaked their systems in drugs and alcohol; shaved their heads and covered their bodies with tattoos; convinced themselves that they are hard, impossible to penetrate; surrendered their identity to a gang—all to hide themselves, from themselves.

When they were little, they were abused. They were defenseless; they were victims. As they got older, they vowed to be strong. Being strong meant inflicting pain. That is what the powerful figures in their lives did to them. Either/or, black or white, the preyed-upon and the predators. What is fascinating is, this “nature, red in tooth and claw” view of reality often butts up against an inner world that is pure fantasy.

The former drug dealer with the gold tooth? His mother was a crack cocaine addict who turned tricks on the corner. In fourth grade, he came out for recess and looked across the street to see his mother climbing into a van with a trick. “No boy should ever have to see his mother doing that,” he blurted out one afternoon in a behavior group.

The short Latino in the front row covered with gang tattoos from his ears to his fingernails? Like his father, he has committed a murder. His father was in prison serving a life sentence when his conviction was suddenly overturned on a technicality. A few days after he got out, he found that his wife had taken up with another man while he was behind bars and promptly burned the house down.

A ten-year-old can’t deal with a mother who is on the street, working as a prostitute. A twelve-year-old can’t handle a father who gets drunk night after night, beats him and his mother, and keeps threatening to burn the house down—again. Sometimes, the only defense is fantasy, and these fantasies are often as delicate as they are elaborate. For years, the Latino gangbanger convinced himself that his dangerous, drug-dealing father was really an undercover agent for the DEA. His dad had infiltrated a gang of Colombians, and as soon as the DEA took them down, his dad was going to abandon the act and use his retirement money to buy his family a home on a hillside in Mexico, overlooking the ocean.

That fantasy is all the boy has left after his father was stabbed to death outside a bar in San Marcos. He cannot imagine living without it, just as he cannot imagine climbing out of the gang shell he has encased himself in. But in Capital Offenders, he will have to face the truth about his father, and the mother who never protected him, and his half dozen criminal uncles. This will require a great leap of faith, for like every boy in this room, he grew up knowing he could trust no one, least of all the adults entrusted with his care.

One word is used more often than any other in Giddings: “empathy.” Everything that happens on campus, from the behavior groups to the football team, is designed to foster empathy. It is ironic that empathy is a word that connotes soft, feminine feelings in “The Free,” as the kids call the world outside the fence. Inside the fence, it describes a rigorous, demanding, life-and-death struggle.

“People tend to think that empathy leads to forgiveness, but forgiveness is too easy, way too easy,” says Linda Reyes. “Kids say, ‘I’m sorry for what I did, I forgive myself, I’m going to move past it.’ Empathy is far more difficult. Having empathy means taking responsibility. It means making a choice: the things a youth has done to others will never happen to someone else because of him. In a sense, empathy means being your own father, your own mother.”

The boys in this small, square room all ran. It is important to understand that. They stabbed or brutally beat someone, and took off running. They fired shots from a car into a house at the exact moment when every member of the family was home and then the driver floored it and the car fishtailed up the street. In a way, the prison system allows criminals to keep on running because it does not make them confront themselves. And when they come out, they are indeed angrier, meaner, and dumber than when they went in.

“In Giddings, they have to stop running,” says Dr. Corinne Alvarez-Sanders, Linda Reyes’s successor as the State School’s director of clinical services. “Developing empathy holds them accountable in a very agonizing way. What’s harder: being forced to look at yourself and what you did, or sitting in a cell day after day?”

Alvarez-Sanders is right. According to studies done by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 75 percent of youth eighteen and under who are sentenced to terms in state prisons are released before they reach age twenty-two. Ninety-three percent of the population that are sentenced to prison while still in their teens complete their minimum sentences before reaching age twenty-eight.

Since violent young offenders are going to get out, society has to answer several questions: Do we want to try to treat this population before they are released and move in next door? Or do we want to keep sending them back to The Free, hardened and without a future? Without empathy? The answer seems obvious. And yet Texas, which loves its law-and-order image, is one of very few states that has intense, systematic programs designed to alter the lives of violent young offenders.

If empathy has a special meaning inside the fence, so does the word “thug.” To the public, all 390 teenagers confined in Giddings State School are thugs—that is why they are there. But ask a veteran Jay-Ko, someone who has spent years working eight-hour shifts in the dorms, and she will search her memory before naming a kid who illustrates “the kind of young man prisons are built to hold,” a kid who is “heartless,” “cold-blooded,” or has “nothing inside but ashes.” Staff psychologists quote the DSM-IV-TR—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of the profession—on antisocial personality disorder, but in the end, their definition of “thug” is the same as that of the frontline staff: a true thug is someone who has no capacity for empathy; who will attack and hurt again and again, and regard each assault as a manifestation of how the world works.

“Fronting,” or faking empathy, looms large in Giddings, particularly in Capital Offenders. A youth who is smart enough to realize he has no feelings for others is also smart enough to realize an early release depends to a large extent on his ability to demonstrate empathy. If he can’t do that, he will try to front.

To get over, he will have to give a great performance, day after grueling day. The audience—his peers and his therapists—is as tough as the one in the workshops at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute, where the great method actors learned their craft. They will be watching and wondering and probing to see if the emotions a boy expresses are genuine.

“A kid had better be ready to be authentic in Capital Offenders,” says Margie Soto, a veteran therapist. “He can try to front his way through, thinking, ‘Oh yeah, I can play along. I can make stuff up and give them what they want and it won’t touch me.’ He can try, but it catches up with him.

“He can’t hide from the group. Day in and day out, he is with the same people, in group and in the residence. The kids get to know what buttons to push, and when to push them. Day in and day out, he gets asked, ‘What’s going on? What’s happening?’ Pretty soon, that’ll trigger a response that’s real. The stories he’s made up, the lies he’s telling, the junk, the trash, the secrets, it will all come out.”

Since Giddings gets “the worst of the worst,” it seems logical to assume that a large percentage have full-blown antisocial personality disorders that no program, however intense, can touch. Most kids arrive acting like career criminals—“I did my crime, I just wanna do my time.” It is common for a kid in an orange jumpsuit to throw down the list of thinking errors he has been told to memorize and shout, “Fuck this shit, man! Just send me to fucking prison! This is fucking bullshit.”

But episodes like that do not mean a youth is a true thug.

“We have to be cautious about ruling out kids in the beginning,” says Linda Reyes. “They all come through the gate looking like psychopaths. They’re kids, they can develop, they can change.”

Since the inception of the Capital Offenders program in 1988, Dr. Reyes, Dr. Alvarez-Sanders, and, currently, Dr. Ann Kelley have been clinical directors. Asked separately and at different times what percentage of the Giddings population they would classify as true psychopaths, each came up with the same figure: between 5 and 6 percent.

“Those who are devoid of empathy are a relatively small part of the Giddings population,” Reyes explains. “That means we can work with ninety-five percent of the population. What happens is, they take the first step and begin to explore their feelings. They experience the range and subtlety of emotions. They connect with others. Having done that, they can no longer live in an antisocial world where everything is black and white and there is no concept of the other.”

Back in the Capital Offenders bunker, a slight youth who shot his best friend to death has been waving his hand in the air. When Kelley finally calls on him, he says, “Crime stories, miss. We’ll be telling our crime stories.”

“We have to tell everything that we did, right from the beginning,’’ adds a tall youth with a deep voice and heavy eyelids. “We can’t be skipping over anything.”

After each boy narrates his life story—a process that will take months to get through—a dramatic change comes over the COG bunker. Life stories are about what was done to these boys; the next step—crime stories—will be about what they did to others. A therapist will drape an arm around a boy and stroke his head when he breaks down and sobs while telling his life story. When he tells his crime story, that same therapist turns very tough. She will go after him, and stay after him, until he faces the horrors he has inflicted.

A tall youth with a narrow face and deep-set, penetrating black eyes stands up, tucks his sweatshirt into his elastic-band prison pants, sits down, and raises his hand. His name is Ronnie and he was part of a gang that did a home invasion and assaulted an elderly couple. They ended up kidnapping the couple, intending to drain their checking account. If the elderly gentleman had not escaped, Ronnie would have killed him.

“We’re supposed to be telling everything about ourselves in here. Well, what if we tell things about our parents and they’re not exactly what you’d call ‘prosocial’ types?” Ronnie asks. “What if we tell things that could get them locked up?”

“Thank you, thank you for asking,” Kelley replies.

“And what about our own selves?” Ronnie interjects before Kelley can continue. “Know what I’m saying? What if we get into things we maybe did that maybe haven’t come to light? What if we tell things we can be arrested for?”

“Let’s go through this carefully, so we all know where we stand,” Kelley says slowly.

Kelley outlines the multiple roles therapists play in a correctional institution. They are not just caretakers, helping damaged youth put their psyches together. They are also evaluators who have to decide if a boy is on his way to becoming someone who can live in society, or if he is a manipulator trying to front his way through and is likely to commit a serious offense if released.

Therapists are also mandated reporters. If they discover a boy is planning to assault someone, or planning to hurt himself, or actively planning to escape, they are duty-bound to stop it.

“If you were abused as a child and the perpetrator is endangering another child, we have to report that. Is that understood?” Kelley asks.

The boys are listening too closely even to nod.

“A lot of the things you did, you didn’t get caught for,” Kelley continues. “Part of Capital Offenders is accepting responsibility. We want you to tell us what you have done. We want you to be honest.”

Kelley goes on to explain that therapists are required to report crimes that have not come to light. If a boy divulges the exact details of a crime, things like the date, time, location, and the names of accomplices, the therapists are required to report it. But Kelley also stresses that uncovering and reporting crimes is not what COG is about. This means the boys and the therapists will walk a fine line. Tell the truth about what you did, but not in such detail that a therapist feels compelled to call the cops back in your hometown.

No doubt inventorying their criminal careers, the young men think this through in silence. Kelley waits and then asks, “What have you heard about role plays?”

A Latino sitting in the front row waves his hand back and forth, begging to be called on. Kelley does and he breaks into a huge, infectious grin.

“Miss, I hear role plays are real scary. Like, if you got whupped as a kid with a belt, miss? They, like, pretend to hit you with a belt.”

Kelley’s eyes search the group until they land on a powerfully built African-American wearing standard-issue TYC glasses with huge black plastic frames.

“Josh, you were in the last group,” Kelley says. “What can you tell us about role plays?”

Most of these young men were born into families where Chaos, the most primitive god of all, reigned supreme. But they also share at least one piece of good luck: they committed their crimes in Texas. Josh may be the luckiest of all.

There is a mechanism in the sentences these young men are serving that puts the decisions about a youth’s future in his hands, and in the hands of the professionals who know him best, the treatment staff at Giddings. If a boy washes out of Capital Offenders, he will almost surely be transferred from Giddings to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, the adult prison system. During the previous Capital Offenders group, Josh became so incensed at a peer he thought was “withholding”— refusing to reveal the truth—he punched him in the face during a break. He was, of course, immediately removed from the group and taken to the security unit, where a hearing was held. Josh was placed in a behavior management program, meaning he ate, slept, and went to school in the security unit. Meanwhile, Giddings officials were trying to decide what to do with him.

They contemplated filing assault charges and starting the machinery that would send Josh to prison, where he would spend the next twenty-five years. Finally, they decided that after thirty days in the security unit, Josh could come back to the general population on phase zero, starting all over again in an orange jumpsuit. Last year, Josh was the best player on the football team. This year, because of the punch he threw, he is not eligible to play. It took Josh six months of near-flawless behavior to work his way back up to phase three and join the next Capital Offenders group in this room.

“A role play is an experience that’s out of this world,” Josh says, a sense of wonder in his voice. “One moment, you are in the room. The next moment, you are back there as a kid. You’re really there!”

“Role plays are about connecting thoughts with feelings,” Kelley comments. “A lot of you haven’t let yourselves feel. That’s dangerous. If you can’t feel for yourself, you won’t feel for anybody else. You’ll go out there and reoffend.”

Any therapist who specializes in working with troubled adolescents knows that there is no one best way to reach them, no silver bullet that will hit a youth between the eyes and turn his life around. The best programs are eclectic and pragmatic, trying out approaches borrowed from sociology, psychology, and biochemistry, using them all, betting hunches, hoping to get lucky, seeing what works. This is especially true of Capital Offenders.

When Linda Reyes arrived in Giddings in the late 1980s, how a youth behaved while incarcerated did not count for much. If he did not commit a serious assault on a staff member or another youth, the TYC had to release him the day he turned twenty-one, no matter how serious his crime or how likely the State School staff thought he was to reoffend. As Giddings began to fill up with young murderers in the late eighties, Reyes scrambled to create a program that would somehow lower the risk that vio- lent youth would turn back to violence after they were released. The program had to be high impact, and the impact had to happen fast. Many were nearing their twenty-first birthdays.

“Imagine the feeling, listening to a young murderer describe his crimes, asking him, ‘You did what, how many times?’ and trying to not let anything show on your face,” Reyes recalls. “You’re thinking, This kid will be back on the streets in a year or two if he behaves. We don’t have the luxury to do talk therapy for a year or two. These kids are going to get out.”

Reyes knows that in order to survive the trauma of his childhood, a youth begins to think like a warrior, equating being stoic with being strong; being hard, closed off from yourself, with being a man. Two feelings predominate: anger and the drive for power.

“Listening to their stories, I saw a lack of empathy in these kids,” Reyes recalls. “They were full of anger, hostility, aggression, resentment, and they refused to accept responsibility. The more stories I heard, the more that empathy seemed to be the critical thing. Empathy keeps you from doing something that might harm someone. We had to find a way to build empathy.”

Reyes hit upon the idea of having youth reenact the key events in their lives. Drama, she thought, might be a way for them to reach back and relive events. Reenacting key scenes in their lives in a setting that is safe gives them a chance to experience the emotions they have kept walled off inside. Drama is a way to break through that “I’m tough, nothing touches me” shield they erect. If they can fully experience the events that have shaped them, they will, in effect, begin to discover their own humanity.

“When victimizers numb their feelings, it is a global shutdown of emotion,” Reyes says. “You can’t choose which feelings to shut down; if you shut down, you shut down everything. Psychodrama is one of the quickest ways to get a youth back in touch with his emotions. Once he has done that, he can go on to explore the forces that led to incarceration.”

For these reasons, at the end of every life story and every crime story, the COG bunker turns into a stage as bare as the ancient Greeks used. The boys and their therapists become actors. While the boy who has just finished his narrative slumps in a corner, the group huddles with the therapists in an opposite corner or out in the hall, where they choose the incidents to reenact, assign roles, create dialogue. The acting in the makeshift dramas is usually stilted in the beginning, but quickly becomes very real. The most minimal presentation can convince a boy his past is unfolding before his eyes. As Josh said, “You’re really there!”

There are two role plays at the end of every crime story. In the first, the boy plays himself, reenacting his crime exactly as it happened. In the second, an exercise in empathy that can be terrifying, the boy plays his own victim.

Kelley explains that taking part in a role play is going to be difficult. You are going to be asked to play an abusive father, and you may have a father who beat you, she says. You are going to be asked to reenact a murder, and you may be responsible for taking someone’s life. Don’t try to back out if you are feeling overwhelmed and think you can’t do it. Tell yourself, This is for my peer. I’m doing it to help him.

Kelley pauses for a moment and focuses on the tattoos on the arms of the young man wearing granny glasses in the front row.

“How many of you are gang involved right now?” she inquires.

Gang activity is confronted from the day a youth enters the State School. So that they will get beyond their gang identities and learn to deal with one another as individuals, youth from rival gangs are intentionally placed in the same dorm. To their astonishment, rival gang members often end up as best friends. Exploring why a youth joined a gang and put his future in jeopardy is a big part of Capital Offenders.

One hand goes up slowly; then two, three, four. Now that it’s safe, another four raise their hands.

“You wouldn’t mark up your body if you didn’t have a lot of affection for your gang,” Kelley says. “We expect you to get in there and work on that. But let me warn you: if we find you are involved in gang-related incidents, there will be immediate consequences. Gang involvement will not be tolerated.”

Kelley asks the therapists if they have anything to add; all six shake their heads no. They already know the boys well, having spent the past six weeks putting the group together. They’ve assessed personalities and mixed gang affiliations. They’ve balanced ages and races; seriousness of offenses and sentence lengths; time served with release dates. They took the boys on a “trust walk,” an exercise in which a blindfolded boy must rely on another boy, often the very person he has identified as trusting the least—the person he thinks is most likely to hurt him. A trust walk forces the boys to face those fears and makes them begin to rely upon one another. It also gives the psychologists a peek at the dynamics of the group, an insight into how the boys will interact when the work begins.

The psychologists have divided the eighteen boys into two groups of nine—nine being the maximum number for therapy this rigorous. Each group will have a Ph.D. psychologist, an experienced therapist, and an intern therapist. There is a husband-and-wife team among the therapists, Frank and Margie Soto. Frank will be in Capital Offenders Group A, Margie in Capital Offenders Group B. They have been working at Giddings in various positions for seventeen years and are Capital Offenders veterans, but they are nervous, as they always are when a new group is starting.

It is not so much the physical danger, although that concern is always present. It is more the realization that for the next six months or more, they are going to be sharing their lives with kids who have been through hell and gone on to inflict hell on others. It is knowing that every night, they will climb into the cab of their Ford pickup and drive home, physically and emotionally spent.

Linda Reyes knows all about that. After she developed Capital Offenders and worked in Giddings for seven years, Reyes was promoted to the TYC main office in Austin, where she is now the deputy executive director, the agency’s number two position, a job that does not require her to get into a bunker with eight or nine murderers. Reyes loved the work she did at Giddings; but after so many years, she was exhausted.

“I felt like I was descending into hell to save their souls,” Reyes says. “The bodies begin to stack up in the psyche. After a while, there isn’t any more room.”

Kelley warns the boys that Capital Offenders gets off to a running start. She tells them that each nine-member group will be meeting in the cottage that very evening to decide who will be the first to tell his life story.

“Think about it before you volunteer,” she cautions. “It isn’t going to be as easy as you might think.”

Capital Offenders typically gets off to a rocky start. A boy who volunteers to go early usually has a macho “What’s the big deal? I can do this” attitude. He begins his narrative; the group and the therapists consider it sketchy and start to probe, and suddenly, the boy finds himself up against events he has spent years trying to forget. He falters, halts, starts again, falters, and finally stops. The therapists keep jump-starting him, all the while warning the group, “See, it isn’t easy. When it is your turn, you better be ready.”

Ronnie, the boy who kidnapped the elderly couple, is wondering about volunteering to go first. When he went out for football, it was the first time he had participated in an organized activity other than a drive-by shooting. The first day of practice, he put his shoulder pads on backward. Now, he is a team leader and is learning how good it feels to accomplish something. He is thinking that if he goes first, he will get the same feeling in Capital Offenders. But that isn’t the main reason why he is considering going first.

“I want to talk about all the shit that’s happened in my life,” Ronnie says. “I just really want to get it all out there. I’ve gotten really tired, dragging it around.”

From the Hardcover edition.

“LOOKING LIKE PSYCHOPATHS”

“Tell us what you know about Capital Offenders,” Kelley asks the group.

Up until this moment, the boys’ reactions have been as uniform as their haircuts and clothing. Heads nodded when a yes was required, went sideways when the answer was no. Now, the masks are coming off. The youth with one eye breaks into a slow grin. A boy with peaked features and startling blue eyes in the second row waves his hand in the air. He looks up, surprised to see it there.

“Life Stories, miss. We’ll be telling our Life Stories,” says a small, somber black youth with large eyes. He inflects the words “Life Stories” in a way that makes it plain they are uppercase. Those two words are al- ways capitalized in the TYC resocialization dialect these young men have learned to speak.

“You can’t leave anything out! You go over it and over it until it’s all out there in the open,’’ adds a youth with a solid-gold front tooth, the symbol of a successful drug dealer.

“You can’t be fronting. No way can you front your way through,” declares a powerfully built young man in the first row. He is wearing granny glasses and could pass for a scholar-athlete if his forearms and biceps weren’t so heavily gang-tattooed.

“You can’t front empathy,” agrees a slight, boyish Korean-American. “If it ain’t real, you got to get real. You can’t be hiding behind no thinking errors.”

“Life stories.” “Empathy.” “Thinking errors.” It turns out that human behavior and the programs designed to alter it are inextricably tied to language. The fact that the national debate over delinquency issues rarely, if ever, reaches a level where language is explored is one reason why the more lofty the setting—a mahogany-paneled legislative hearing room in a state capital; a Senate subcommittee room with chandeliers and marble floors in Washington, D.C.—the more ersatz the debate. Frontline treatment specialists in Giddings take little heed of congressional hearings such as “Is Treating Juvenile Offenders Cost-Effective?” The people who actually do the work tend to view splashy hearings as little more than a platform for grandstanding politicians, one-issue zealots, and academics pushing a thesis. On the front lines, that question has been settled: treatment works.

It is one thing to say that about programs in a state institution. Taxpayers are picking up the bills, and the outcomes, no matter how scientifically they are evaluated, remain suspect because state institutions collect their own data and measure their own results. It is quite another when the marketplace says that intense treatment changes the trajectory of troubled teenagers’ lives. The best evidence of that is the “emotional-growth boarding schools” that have sprung up west of the Rockies in the last twenty years at a rate that rivals the growth of traditional prep schools in New England in the nineteenth century. These schools cater to teenagers who are so deeply into drugs and self-destructive behavior, their parents are terrified they will not live to turn twenty. The tuition at CEDU, the oldest of the emotional-growth, or “therapeutic,” boarding schools (founded in 1967 in Palm Springs, California), is well over $100,000 a year. If the cost is astounding, so are the results. Families that can afford a six-figure annual tuition would not keep enrolling their children in CEDU if they did not see tremendous changes.

CEDU is at one end of the socioeconomic spectrum, Giddings is at the other. And yet the programs they operate are very similar. In both places, teenagers begin by memorizing a language they will eventually internalize. In both schools, the students come close to running the programs themselves.

The information the boys are practically shouting at Kelley did not come only from a manual or a lecture. Much of it came from their peers. They know so much about what is going to happen because after the eighteen boys were selected from the main Giddings population, they were transferred to Cottages 5-A and 5-B, where they moved in with a dozen students who had recently completed Capital Offenders. No introduction presented by a staff member, no matter how eloquent, carries the weight of a COG veteran who says, “Listen up, this is what they gonna have you do.’’

The eighteen boys in this room have spent the last two to four years immersed in the resocialization program that structures life in the State School. Resocialization is a rethinking of the oldest concept in juvenile justice—rehabilitation—and in some ways, the word is poorly chosen. It assumes that some early socialization occurred in the lives of these boys, and for a majority, that did not happen.

An average, functioning family acts as a crucible where children are socialized, i.e., civilized, meaning they learn to relate to others through the relationships they form with parents and siblings. Most of the boys in this room come from families where the adults were drunk, high, street criminals, or in prison. In their families, “socialization” too often meant getting together to shoot hard drugs.

Giddings is not an attempt to re-create the family. That never works, in institutions, group homes, or foster homes. Kids instinctively rebel—This is bullshit! You’re not my real dad! Instead, Giddings is a gigantic bell jar where 390 young offenders are under intense observation sixteen hours a day. Over the past few years, these boys have spent countless hours in one kind of a group or another, acquiring skills that were not ingrained in their families of origin.

“Thinking errors” are at the heart of this process. Along with clothing, one of the first things a youth receives upon arriving in a TYC institution is Changing Course: A Student Workbook for Resocialization. As soon as he gets his layout down, he is told to turn to Chapter Three and memorize the list of nine thinking errors. They are: deceiving, downplaying, avoiding, blaming, making excuses, jumping to conclusions, acting helpless, overreacting, and feeling special. All of us employ these techniques at one time or another. These kids have used them in a way that has harmed others, and will allow them to keep on harming others, if their thought processes are not confronted and altered.

“Thinking errors are used to justify criminal behavior,” says Linda Reyes. “The error is in the justification, not in the fact. A youth can state true facts: I was sexually abused. Therefore, I sexually abused my sister. The thinking error is not in the facts. It is in the justification based on the facts.”

Do all newly incarcerated young felons hate memorizing thinking errors? They certainly do. Do they do it by rote, as if they were memorizing words in a foreign language? Of course. Learning a new language is like picking up a tool chest. The real work is learning to use those tools— sitting in a group and stopping a peer in midsentence with, “Hold on, right there. You just used a thinking error. Can you name it?” and then helping him see he is “avoiding” or “downplaying.” This is an arduous practice, akin to a young musician learning the scales. It goes on and on and on, day after day. Walk into any cottage after dinner and the boys are likely to be sitting in a circle, conducting a behavior group. Typically, a boy has erupted in anger at a juvenile corrections officer—“Jay-Ko” in the Giddings vernacular—who ordered him to clean up his “PA,” or personal area, a small clothes closet that sits at the foot of every bed. Instead of referring the boy to the security unit for being disobedient, the Jay-Ko called a behavior group. The group may spend hours in the circle, trying to help the boy understand why he got angry, and how anger feeds into his offense cycle.

The boys entering Capital Offenders are about to become archaeologists of the self, slowly and methodically sifting through their own lives. Each youth will spend two to three three-and-a-half-hour sessions telling his life story. At first glance, this does not seem daunting. Most of us, in one way or another, are telling one another our life stories all the time. But for these boys, the task is terrifying. They have soaked their systems in drugs and alcohol; shaved their heads and covered their bodies with tattoos; convinced themselves that they are hard, impossible to penetrate; surrendered their identity to a gang—all to hide themselves, from themselves.

When they were little, they were abused. They were defenseless; they were victims. As they got older, they vowed to be strong. Being strong meant inflicting pain. That is what the powerful figures in their lives did to them. Either/or, black or white, the preyed-upon and the predators. What is fascinating is, this “nature, red in tooth and claw” view of reality often butts up against an inner world that is pure fantasy.

The former drug dealer with the gold tooth? His mother was a crack cocaine addict who turned tricks on the corner. In fourth grade, he came out for recess and looked across the street to see his mother climbing into a van with a trick. “No boy should ever have to see his mother doing that,” he blurted out one afternoon in a behavior group.

The short Latino in the front row covered with gang tattoos from his ears to his fingernails? Like his father, he has committed a murder. His father was in prison serving a life sentence when his conviction was suddenly overturned on a technicality. A few days after he got out, he found that his wife had taken up with another man while he was behind bars and promptly burned the house down.

A ten-year-old can’t deal with a mother who is on the street, working as a prostitute. A twelve-year-old can’t handle a father who gets drunk night after night, beats him and his mother, and keeps threatening to burn the house down—again. Sometimes, the only defense is fantasy, and these fantasies are often as delicate as they are elaborate. For years, the Latino gangbanger convinced himself that his dangerous, drug-dealing father was really an undercover agent for the DEA. His dad had infiltrated a gang of Colombians, and as soon as the DEA took them down, his dad was going to abandon the act and use his retirement money to buy his family a home on a hillside in Mexico, overlooking the ocean.

That fantasy is all the boy has left after his father was stabbed to death outside a bar in San Marcos. He cannot imagine living without it, just as he cannot imagine climbing out of the gang shell he has encased himself in. But in Capital Offenders, he will have to face the truth about his father, and the mother who never protected him, and his half dozen criminal uncles. This will require a great leap of faith, for like every boy in this room, he grew up knowing he could trust no one, least of all the adults entrusted with his care.

One word is used more often than any other in Giddings: “empathy.” Everything that happens on campus, from the behavior groups to the football team, is designed to foster empathy. It is ironic that empathy is a word that connotes soft, feminine feelings in “The Free,” as the kids call the world outside the fence. Inside the fence, it describes a rigorous, demanding, life-and-death struggle.

“People tend to think that empathy leads to forgiveness, but forgiveness is too easy, way too easy,” says Linda Reyes. “Kids say, ‘I’m sorry for what I did, I forgive myself, I’m going to move past it.’ Empathy is far more difficult. Having empathy means taking responsibility. It means making a choice: the things a youth has done to others will never happen to someone else because of him. In a sense, empathy means being your own father, your own mother.”

The boys in this small, square room all ran. It is important to understand that. They stabbed or brutally beat someone, and took off running. They fired shots from a car into a house at the exact moment when every member of the family was home and then the driver floored it and the car fishtailed up the street. In a way, the prison system allows criminals to keep on running because it does not make them confront themselves. And when they come out, they are indeed angrier, meaner, and dumber than when they went in.

“In Giddings, they have to stop running,” says Dr. Corinne Alvarez-Sanders, Linda Reyes’s successor as the State School’s director of clinical services. “Developing empathy holds them accountable in a very agonizing way. What’s harder: being forced to look at yourself and what you did, or sitting in a cell day after day?”

Alvarez-Sanders is right. According to studies done by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 75 percent of youth eighteen and under who are sentenced to terms in state prisons are released before they reach age twenty-two. Ninety-three percent of the population that are sentenced to prison while still in their teens complete their minimum sentences before reaching age twenty-eight.

Since violent young offenders are going to get out, society has to answer several questions: Do we want to try to treat this population before they are released and move in next door? Or do we want to keep sending them back to The Free, hardened and without a future? Without empathy? The answer seems obvious. And yet Texas, which loves its law-and-order image, is one of very few states that has intense, systematic programs designed to alter the lives of violent young offenders.

If empathy has a special meaning inside the fence, so does the word “thug.” To the public, all 390 teenagers confined in Giddings State School are thugs—that is why they are there. But ask a veteran Jay-Ko, someone who has spent years working eight-hour shifts in the dorms, and she will search her memory before naming a kid who illustrates “the kind of young man prisons are built to hold,” a kid who is “heartless,” “cold-blooded,” or has “nothing inside but ashes.” Staff psychologists quote the DSM-IV-TR—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of the profession—on antisocial personality disorder, but in the end, their definition of “thug” is the same as that of the frontline staff: a true thug is someone who has no capacity for empathy; who will attack and hurt again and again, and regard each assault as a manifestation of how the world works.

“Fronting,” or faking empathy, looms large in Giddings, particularly in Capital Offenders. A youth who is smart enough to realize he has no feelings for others is also smart enough to realize an early release depends to a large extent on his ability to demonstrate empathy. If he can’t do that, he will try to front.

To get over, he will have to give a great performance, day after grueling day. The audience—his peers and his therapists—is as tough as the one in the workshops at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute, where the great method actors learned their craft. They will be watching and wondering and probing to see if the emotions a boy expresses are genuine.

“A kid had better be ready to be authentic in Capital Offenders,” says Margie Soto, a veteran therapist. “He can try to front his way through, thinking, ‘Oh yeah, I can play along. I can make stuff up and give them what they want and it won’t touch me.’ He can try, but it catches up with him.

“He can’t hide from the group. Day in and day out, he is with the same people, in group and in the residence. The kids get to know what buttons to push, and when to push them. Day in and day out, he gets asked, ‘What’s going on? What’s happening?’ Pretty soon, that’ll trigger a response that’s real. The stories he’s made up, the lies he’s telling, the junk, the trash, the secrets, it will all come out.”

Since Giddings gets “the worst of the worst,” it seems logical to assume that a large percentage have full-blown antisocial personality disorders that no program, however intense, can touch. Most kids arrive acting like career criminals—“I did my crime, I just wanna do my time.” It is common for a kid in an orange jumpsuit to throw down the list of thinking errors he has been told to memorize and shout, “Fuck this shit, man! Just send me to fucking prison! This is fucking bullshit.”

But episodes like that do not mean a youth is a true thug.

“We have to be cautious about ruling out kids in the beginning,” says Linda Reyes. “They all come through the gate looking like psychopaths. They’re kids, they can develop, they can change.”

Since the inception of the Capital Offenders program in 1988, Dr. Reyes, Dr. Alvarez-Sanders, and, currently, Dr. Ann Kelley have been clinical directors. Asked separately and at different times what percentage of the Giddings population they would classify as true psychopaths, each came up with the same figure: between 5 and 6 percent.

“Those who are devoid of empathy are a relatively small part of the Giddings population,” Reyes explains. “That means we can work with ninety-five percent of the population. What happens is, they take the first step and begin to explore their feelings. They experience the range and subtlety of emotions. They connect with others. Having done that, they can no longer live in an antisocial world where everything is black and white and there is no concept of the other.”

Back in the Capital Offenders bunker, a slight youth who shot his best friend to death has been waving his hand in the air. When Kelley finally calls on him, he says, “Crime stories, miss. We’ll be telling our crime stories.”

“We have to tell everything that we did, right from the beginning,’’ adds a tall youth with a deep voice and heavy eyelids. “We can’t be skipping over anything.”

After each boy narrates his life story—a process that will take months to get through—a dramatic change comes over the COG bunker. Life stories are about what was done to these boys; the next step—crime stories—will be about what they did to others. A therapist will drape an arm around a boy and stroke his head when he breaks down and sobs while telling his life story. When he tells his crime story, that same therapist turns very tough. She will go after him, and stay after him, until he faces the horrors he has inflicted.

A tall youth with a narrow face and deep-set, penetrating black eyes stands up, tucks his sweatshirt into his elastic-band prison pants, sits down, and raises his hand. His name is Ronnie and he was part of a gang that did a home invasion and assaulted an elderly couple. They ended up kidnapping the couple, intending to drain their checking account. If the elderly gentleman had not escaped, Ronnie would have killed him.

“We’re supposed to be telling everything about ourselves in here. Well, what if we tell things about our parents and they’re not exactly what you’d call ‘prosocial’ types?” Ronnie asks. “What if we tell things that could get them locked up?”

“Thank you, thank you for asking,” Kelley replies.

“And what about our own selves?” Ronnie interjects before Kelley can continue. “Know what I’m saying? What if we get into things we maybe did that maybe haven’t come to light? What if we tell things we can be arrested for?”

“Let’s go through this carefully, so we all know where we stand,” Kelley says slowly.

Kelley outlines the multiple roles therapists play in a correctional institution. They are not just caretakers, helping damaged youth put their psyches together. They are also evaluators who have to decide if a boy is on his way to becoming someone who can live in society, or if he is a manipulator trying to front his way through and is likely to commit a serious offense if released.

Therapists are also mandated reporters. If they discover a boy is planning to assault someone, or planning to hurt himself, or actively planning to escape, they are duty-bound to stop it.

“If you were abused as a child and the perpetrator is endangering another child, we have to report that. Is that understood?” Kelley asks.

The boys are listening too closely even to nod.

“A lot of the things you did, you didn’t get caught for,” Kelley continues. “Part of Capital Offenders is accepting responsibility. We want you to tell us what you have done. We want you to be honest.”

Kelley goes on to explain that therapists are required to report crimes that have not come to light. If a boy divulges the exact details of a crime, things like the date, time, location, and the names of accomplices, the therapists are required to report it. But Kelley also stresses that uncovering and reporting crimes is not what COG is about. This means the boys and the therapists will walk a fine line. Tell the truth about what you did, but not in such detail that a therapist feels compelled to call the cops back in your hometown.

No doubt inventorying their criminal careers, the young men think this through in silence. Kelley waits and then asks, “What have you heard about role plays?”

A Latino sitting in the front row waves his hand back and forth, begging to be called on. Kelley does and he breaks into a huge, infectious grin.

“Miss, I hear role plays are real scary. Like, if you got whupped as a kid with a belt, miss? They, like, pretend to hit you with a belt.”

Kelley’s eyes search the group until they land on a powerfully built African-American wearing standard-issue TYC glasses with huge black plastic frames.

“Josh, you were in the last group,” Kelley says. “What can you tell us about role plays?”

Most of these young men were born into families where Chaos, the most primitive god of all, reigned supreme. But they also share at least one piece of good luck: they committed their crimes in Texas. Josh may be the luckiest of all.

There is a mechanism in the sentences these young men are serving that puts the decisions about a youth’s future in his hands, and in the hands of the professionals who know him best, the treatment staff at Giddings. If a boy washes out of Capital Offenders, he will almost surely be transferred from Giddings to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, the adult prison system. During the previous Capital Offenders group, Josh became so incensed at a peer he thought was “withholding”— refusing to reveal the truth—he punched him in the face during a break. He was, of course, immediately removed from the group and taken to the security unit, where a hearing was held. Josh was placed in a behavior management program, meaning he ate, slept, and went to school in the security unit. Meanwhile, Giddings officials were trying to decide what to do with him.

They contemplated filing assault charges and starting the machinery that would send Josh to prison, where he would spend the next twenty-five years. Finally, they decided that after thirty days in the security unit, Josh could come back to the general population on phase zero, starting all over again in an orange jumpsuit. Last year, Josh was the best player on the football team. This year, because of the punch he threw, he is not eligible to play. It took Josh six months of near-flawless behavior to work his way back up to phase three and join the next Capital Offenders group in this room.

“A role play is an experience that’s out of this world,” Josh says, a sense of wonder in his voice. “One moment, you are in the room. The next moment, you are back there as a kid. You’re really there!”

“Role plays are about connecting thoughts with feelings,” Kelley comments. “A lot of you haven’t let yourselves feel. That’s dangerous. If you can’t feel for yourself, you won’t feel for anybody else. You’ll go out there and reoffend.”

Any therapist who specializes in working with troubled adolescents knows that there is no one best way to reach them, no silver bullet that will hit a youth between the eyes and turn his life around. The best programs are eclectic and pragmatic, trying out approaches borrowed from sociology, psychology, and biochemistry, using them all, betting hunches, hoping to get lucky, seeing what works. This is especially true of Capital Offenders.

When Linda Reyes arrived in Giddings in the late 1980s, how a youth behaved while incarcerated did not count for much. If he did not commit a serious assault on a staff member or another youth, the TYC had to release him the day he turned twenty-one, no matter how serious his crime or how likely the State School staff thought he was to reoffend. As Giddings began to fill up with young murderers in the late eighties, Reyes scrambled to create a program that would somehow lower the risk that vio- lent youth would turn back to violence after they were released. The program had to be high impact, and the impact had to happen fast. Many were nearing their twenty-first birthdays.

“Imagine the feeling, listening to a young murderer describe his crimes, asking him, ‘You did what, how many times?’ and trying to not let anything show on your face,” Reyes recalls. “You’re thinking, This kid will be back on the streets in a year or two if he behaves. We don’t have the luxury to do talk therapy for a year or two. These kids are going to get out.”

Reyes knows that in order to survive the trauma of his childhood, a youth begins to think like a warrior, equating being stoic with being strong; being hard, closed off from yourself, with being a man. Two feelings predominate: anger and the drive for power.

“Listening to their stories, I saw a lack of empathy in these kids,” Reyes recalls. “They were full of anger, hostility, aggression, resentment, and they refused to accept responsibility. The more stories I heard, the more that empathy seemed to be the critical thing. Empathy keeps you from doing something that might harm someone. We had to find a way to build empathy.”

Reyes hit upon the idea of having youth reenact the key events in their lives. Drama, she thought, might be a way for them to reach back and relive events. Reenacting key scenes in their lives in a setting that is safe gives them a chance to experience the emotions they have kept walled off inside. Drama is a way to break through that “I’m tough, nothing touches me” shield they erect. If they can fully experience the events that have shaped them, they will, in effect, begin to discover their own humanity.

“When victimizers numb their feelings, it is a global shutdown of emotion,” Reyes says. “You can’t choose which feelings to shut down; if you shut down, you shut down everything. Psychodrama is one of the quickest ways to get a youth back in touch with his emotions. Once he has done that, he can go on to explore the forces that led to incarceration.”

For these reasons, at the end of every life story and every crime story, the COG bunker turns into a stage as bare as the ancient Greeks used. The boys and their therapists become actors. While the boy who has just finished his narrative slumps in a corner, the group huddles with the therapists in an opposite corner or out in the hall, where they choose the incidents to reenact, assign roles, create dialogue. The acting in the makeshift dramas is usually stilted in the beginning, but quickly becomes very real. The most minimal presentation can convince a boy his past is unfolding before his eyes. As Josh said, “You’re really there!”

There are two role plays at the end of every crime story. In the first, the boy plays himself, reenacting his crime exactly as it happened. In the second, an exercise in empathy that can be terrifying, the boy plays his own victim.

Kelley explains that taking part in a role play is going to be difficult. You are going to be asked to play an abusive father, and you may have a father who beat you, she says. You are going to be asked to reenact a murder, and you may be responsible for taking someone’s life. Don’t try to back out if you are feeling overwhelmed and think you can’t do it. Tell yourself, This is for my peer. I’m doing it to help him.

Kelley pauses for a moment and focuses on the tattoos on the arms of the young man wearing granny glasses in the front row.

“How many of you are gang involved right now?” she inquires.

Gang activity is confronted from the day a youth enters the State School. So that they will get beyond their gang identities and learn to deal with one another as individuals, youth from rival gangs are intentionally placed in the same dorm. To their astonishment, rival gang members often end up as best friends. Exploring why a youth joined a gang and put his future in jeopardy is a big part of Capital Offenders.

One hand goes up slowly; then two, three, four. Now that it’s safe, another four raise their hands.

“You wouldn’t mark up your body if you didn’t have a lot of affection for your gang,” Kelley says. “We expect you to get in there and work on that. But let me warn you: if we find you are involved in gang-related incidents, there will be immediate consequences. Gang involvement will not be tolerated.”

Kelley asks the therapists if they have anything to add; all six shake their heads no. They already know the boys well, having spent the past six weeks putting the group together. They’ve assessed personalities and mixed gang affiliations. They’ve balanced ages and races; seriousness of offenses and sentence lengths; time served with release dates. They took the boys on a “trust walk,” an exercise in which a blindfolded boy must rely on another boy, often the very person he has identified as trusting the least—the person he thinks is most likely to hurt him. A trust walk forces the boys to face those fears and makes them begin to rely upon one another. It also gives the psychologists a peek at the dynamics of the group, an insight into how the boys will interact when the work begins.

The psychologists have divided the eighteen boys into two groups of nine—nine being the maximum number for therapy this rigorous. Each group will have a Ph.D. psychologist, an experienced therapist, and an intern therapist. There is a husband-and-wife team among the therapists, Frank and Margie Soto. Frank will be in Capital Offenders Group A, Margie in Capital Offenders Group B. They have been working at Giddings in various positions for seventeen years and are Capital Offenders veterans, but they are nervous, as they always are when a new group is starting.

It is not so much the physical danger, although that concern is always present. It is more the realization that for the next six months or more, they are going to be sharing their lives with kids who have been through hell and gone on to inflict hell on others. It is knowing that every night, they will climb into the cab of their Ford pickup and drive home, physically and emotionally spent.

Linda Reyes knows all about that. After she developed Capital Offenders and worked in Giddings for seven years, Reyes was promoted to the TYC main office in Austin, where she is now the deputy executive director, the agency’s number two position, a job that does not require her to get into a bunker with eight or nine murderers. Reyes loved the work she did at Giddings; but after so many years, she was exhausted.

“I felt like I was descending into hell to save their souls,” Reyes says. “The bodies begin to stack up in the psyche. After a while, there isn’t any more room.”

Kelley warns the boys that Capital Offenders gets off to a running start. She tells them that each nine-member group will be meeting in the cottage that very evening to decide who will be the first to tell his life story.

“Think about it before you volunteer,” she cautions. “It isn’t going to be as easy as you might think.”

Capital Offenders typically gets off to a rocky start. A boy who volunteers to go early usually has a macho “What’s the big deal? I can do this” attitude. He begins his narrative; the group and the therapists consider it sketchy and start to probe, and suddenly, the boy finds himself up against events he has spent years trying to forget. He falters, halts, starts again, falters, and finally stops. The therapists keep jump-starting him, all the while warning the group, “See, it isn’t easy. When it is your turn, you better be ready.”

Ronnie, the boy who kidnapped the elderly couple, is wondering about volunteering to go first. When he went out for football, it was the first time he had participated in an organized activity other than a drive-by shooting. The first day of practice, he put his shoulder pads on backward. Now, he is a team leader and is learning how good it feels to accomplish something. He is thinking that if he goes first, he will get the same feeling in Capital Offenders. But that isn’t the main reason why he is considering going first.

“I want to talk about all the shit that’s happened in my life,” Ronnie says. “I just really want to get it all out there. I’ve gotten really tired, dragging it around.”

From the Hardcover edition.