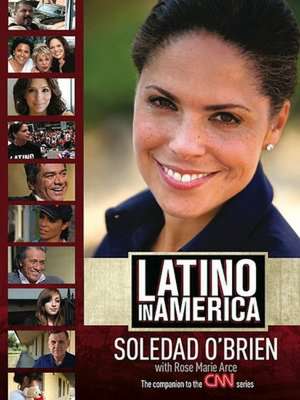

Latino in America: Celebra Books

Autor Soledad O'Brien Rose Marie Arceen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2009 – vârsta de la 18 ani

The definitive tie-in to one of the most heavily anticipated CNN documentaries ever, Latino in America, from top CNN anchor and special correspondent Soledad O’Brien.

Top CNN anchor and special correspondent Soledad O’Brien brings readers closer to today’s Latino experience as well as her own journey in the definitive tie-in to one of the most heavily anticipated CNN documentaries ever, Latino in America. The Latino in America book will deliver more personal and revealing accounts than the documentary and will contain never-before-seen moving interviews, photos, and exclusive insights from O’Brien’s travels across the U.S.

Top CNN anchor and special correspondent Soledad O’Brien brings readers closer to today’s Latino experience as well as her own journey in the definitive tie-in to one of the most heavily anticipated CNN documentaries ever, Latino in America. The Latino in America book will deliver more personal and revealing accounts than the documentary and will contain never-before-seen moving interviews, photos, and exclusive insights from O’Brien’s travels across the U.S.

Watch a Video

Preț: 138.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 208

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.55€ • 27.80$ • 21.97£

26.55€ • 27.80$ • 21.97£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780451229465

ISBN-10: 0451229460

Pagini: 250

Dimensiuni: 148 x 233 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Celebra Trade

Seria Celebra Books

ISBN-10: 0451229460

Pagini: 250

Dimensiuni: 148 x 233 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Celebra Trade

Seria Celebra Books

Notă biografică

Soledad O’Brien is a CNN anchor and correspondent who has produced the award-winning documentaries Black in America and Escape from Jonestown. Her awards include the Emmy, Peabody, DuPont, Gracie Allen, Clara Barton, Hispanic Heritage, and NAACP President’s Awards, among others.

Extras

Chapter Three: Have a Magical Day The day I fly to Orlando to meet Carlos Robles the temperature is as high as it is in his hometown of Fajardo, Puerto Rico. The same humidity, too. Occasional puffs of cool air cut through the midday heat, which hits eighty degrees by noon and hangs there until the sun sets. The weather helps explain why so many Puerto Ricans relocate to Orlando in search of opportunities. "The truth is I wanted a new job and couldn't see myself moving too far north. I can't stand it when it gets below sixty," says Carlos.

He has been in Orlando for two years and so far only the most extreme winter chills (extreme, that is, by Orlando standards) have rattled him. Puerto Ricans are the only U.S. citizens born on a piece of U.S. soil where Latin culture and the Spanish language are dominant. They are not immigrants or the children of immigrants like all the other Latinos. Since 1917 they are U.S. citizens and, despite their island's colonial friction with the United States, they are basically Americans born and bred. Taking a trip to Puerto Rico, lovely as that might be for me, isn't going to tell me much about Latinos in the larger American experience because the island in many ways operates like its own Latino country. So, instead, I've come to Orlando, Florida, a favored destination for islanders looking to come to the mainland.

I meet Carlos in the sun-splashed garden of the Valencia Community College Center for Global Languages, where Carlos is taking a class. Students from all over the world study here to improve their pronunciation and understanding of the English language. They used to call the classes Accent Reduction but no one enrolled. So they renamed them English Conversation class and now they're full.

Carlos is a fair-skinned, chunky guy with short dark hair and a squared-off goatee. He is sweating and antsy and shakes my hand like he's just walked into a do-or-die job interview. When he says, "Eh-lo," I think of my grandmother with her two words of English. I tell Carlos that I know Spanish but that if I were to talk to him in Spanish he'd be doing this story about me. He starts smiling little by little. I recall how my mother used to say "hog-dog" all the time for hot dog and get a snicker of recognition out of him.

Carlos's features could make him from anywhere Latin, except that his Spanish is very Puerto Rican. When he speaks Spanish he replaces his rs with ls and he talks like he's about to start singing. It's a happy form of speech, very homey, almost like teasing. But in English he sounds like he's spitting out phrases. He is hesitant, throwing out each word almost like he's asking the question, "Is this the right word, am I pronouncing it right?" So this guy who was born on American territory, educated in American schools, is about to begin barking out language drills in a classroom so he can communicate with his fellow Americans here in Orlando. He laughs at his whole situation.

I meet another Puerto Rican student in the garden. Santos Martinez is tall, black, bald, and looks like the basketball coach he is. He coaches in English but feels like he's not communicating with the parents. "I can't do that if the fathers keep looking at me like, 'What did he just say?'" says Santos. He rattles off his personal résumé to explain why he's here. "I'm part-time [at] JetBlue, no wife, no kids. In my culture that's a loser." His language limitations have kept him from rising professionally or meeting the American wife he's looking for. Santos, Carlos, and I trade words before class begins. Carlos can't say the ths properly. Instead of "thought," he says "tawt." I ask them what's the most difficult word to pronounce in English and Santos says, "Crocodile." I ask him how you pronounce it in Spanish and suddenly we're all standing there sputtering: "Co-co. Ca-ca-ca." We all begin to laugh.

Carlos's journey to Orlando began in his hometown of Fajardo, known as La Metrópolis del Sol Naciente, the Metropolis of the Rising Sun. It's a small town on the east end of Puerto Rico where recreational boats float in the Atlantic Ocean and big ferries take off for the islands of Vieques and Culebra. Nothing in Fajardo seems to move quickly, not even the cooling breeze that comes off the ocean. Like Orlando, it's a place many people associate with a good vacation.

Carlos worked as a police officer in nearby Carolina, where an international airport sits beside a string of resort hotels, lazy beaches, and a very large shopping mall. His territory included the towns of Loiza and Canóvanas, which have housing complexes with substantial drug problems. Carlos felt he was on a road to nowhere good. The pay was low; his family was threatened by the drug dealers; his mother was always praying for his safety. Homes on the island are very expensive so he felt he'd never be enough to buy something nice. He had to get out. But it made him sad to walk away from the tranquility and tropical weather he loved.

Years earlier, his aunt and uncle had moved their family to Orlando after his uncle was transferred there by the navy. There were a lot of Puerto Ricans there and the family found the weather and atmosphere familiar. Carlos and his family visited so often that his grandmother purchased three small apartments to use as vacation homes for all her kids and grandkids. When Carlos decided to quit his job to search for new opportunities, his grandmother offered him a free apartment in Orlando so he could join his aunt, uncle, and two cousins. He was gone in weeks.

This is a familiar story for many Puerto Ricans who relocate to Orlando. The island has 15 percent unemployment and there isn't enough affordable housing, while there are more opportunities for jobs and homes on the mainland. Jorge Duany, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico, researched the phenomenon of Puerto Ricans moving to Orlando. He discovered official efforts to encourage Puerto Ricans to move to Orlando dating as far back as the 1950s, when central Florida needed more farmworkers and the island's government began a program to encourage migration. That was followed by another contract labor program in the 1970s.

Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens and the island had a lot of trained agricultural workers. Since the island had lower salaries, the Puerto Ricans were a cheap, hardworking domestic labor force. The workers made more money on the mainland, bought homes and stayed. Friends and relatives followed. In 1971, Disney opened and real estate speculation drew even more Puerto Ricans. Disney also liked Puerto Rican workers. They sent representatives to the island to visit schools and job fairs. They even offered cash relocation bonuses at one point.

Orlando in general was exploding with people. The local chamber of commerce estimates one thousand a week were coming at one point. Research by the Pew Hispanic Center in 2002 determined Orlando's Latino population had 300 percent growth since 1980. The U.S. census said the place was adding 347 people a day in 2001, and there's no denying that Puerto Ricans were a big part of that growth. They represent 56 percent of the Orlando Latino population, and that doesn't even count the many Puerto Ricans who travel back and forth.

As the population of Orlando became more Latino, other companies looked to diversify their workforce and offer bilingual services. Puerto Rican employees filled both those goals without having any immigration issues. NASA, just forty miles away, sent recruiters to hunt for talented engineers at the University of Puerto Rico in Mayaguez. Florida Hospital in Orlando signed an affiliation agreement with the University of Puerto Rico in 2005. Between 2000 and 2006, according to census figures, 200,000 of Puerto Rico's 4 million people moved to Florida. After the farmworkers came blue-collar laborers and then professionals. They didn't just come from the island but also from big mainland cities like New York and Chicago, traditional destinations for Puerto Ricans. Almost half the Puerto Ricans in Orlando come from other cities on the mainland, Duany found in his research. He also discovered that the newcomers are mostly white, well educated, and have more than double the median family income of their counterparts back on the island. The move is paying off. When Carlos came to Orlando in 2007, he was hoping to become another Orlando-Rican success story. Very quickly he had a job as a manager at Kay-Bee Toys. There were four managers and he was the only one who spoke Spanish, an asset. He was earning good money. He met Puerto Ricans from New York who were looking to move to Orlando because they found their city so cold and fast-paced. Carlos is funny and friendly and gives off the air of a guy who likes to be liked. He tried hard to fit in with the other managers. But they weren't very friendly. Every time he opened his mouth, they would look at him like he was an idiot. "I cried in my bed because I can't have a conversation with the people. It was really bad," he said.

Like all Puerto Ricans, Carlos was taught English in school and expected to speak it fluently. Yet once he left school, there just weren't opportunities to have real conversations in English. His vocabulary and accent suffered. The Puerto Ricans from New York all spoke English and people expected him to speak it, too. But the white people in Orlando would just smile politely and walk away in the middle of a conversation. "I'd look at them and think, 'That guy has no idea what I just said to him,'" Carlos remembers. The other managers at Kay-Bee Toys wouldn't even smile. They would just bark orders at him as if he was their subordinate, pushing him toward grunt jobs and making jokes behind his back. His supervisor called him a Mexican. Carlos thought it was funny because he was considering joining the Border Patrol at the time and the ads all asked for fluent Spanish speakers.

He tried to let their remarks roll off him but it slowly began to get to him. He'd never felt this way back on the island, where he was a swaggering American police officer bossing around a whole group of motorcycle cops patrolling for drug dealers.

"Oh, my God. It was humiliating. I wanted to punch them sometimes," he said. "I just kept telling myself I'd start to speak better and one day I'd be this professional guy they'd look up to."

There are nearly eight hundred students taking the English speech classes at Valencia and it is repeated five times a year. It is a little odd to see Americans taking classes to reduce their accents alongside people coming from foreign countries, but Puerto Ricans are a twist in the discussion of Latinos in U.S. culture.

After Kay-Bee Toys shut down, Carlos decided he wanted to wrap his arms around the language and enrolled in pronunciation class. He is taking a second round, twice a week from 6:00 to 8:30 p.m.

"I'm taking the class because I saw that I can be more professional and I think that I can have a better life and I need to talk English. I'm in the United States, so I need to talk," he said.

"Well, Puerto Rico's part of the United States," I point out.

"Yeah, but we always talk in Spanish. We never talk in English over there."

Carlos looks like he used to have the imposing build of a cop. He wears the reflecting sunglasses you'd expect to see on a police officer who works in warm weather. Inside his classroom, words are written in red that make Carlos's head hurt: kitchen, corner, and victory. Cabinet. Thought.

"The Latinos hate the words with the th and the v," says Marisa Dawson, the teacher. "The Asians have great grammar but they've never had to speak, so their pronunciation is terrible. The Puerto Ricans should know more than the South Americans but they don't. They all learn it in school but it's kind of like learning high school French. If you never use it, you lose it, and when they come here I think they're surprised how much they need it. The South Americans are prepared because they know they won't get anywhere if they can't speak English."

Carlos is sitting between a Colombian guy and a Venezuelan. Neither of them really wants to be in the United States but they were forced to leave their countries. Miguel Ortega was a surgeon back in Colombia and now he's "the cable guy." He tried being a medical assistant when he first got to Orlando but it paid $8 an hour. It is too dangerous in Colombia or he would go back. The paramilitaries killed people where he worked. He is determined to be a doctor again so he is studying to pass the required recertification tests. He has passed the first few but the last one requires English conversation, so he needs this class to work.

Luis Sirit was in the Venezuelan navy as a commander. He also wishes he could go home but he says he is on the wrong side of politics there and that can be deadly.

"I could do just fine in Orlando without learning any English, that's how Latino it is here," he says. "But I'm cleaning swimming pools. I didn't study to clean swimming pools."

Both of the men voice a short list of laments about living in the United States: the food is not fresh, the parties never seem to include music or dancing, the people aren't as close to their families. Luis says he keeps inviting people over to show them how much fun Latinos can be and he says they really enjoy his culture. He especially likes the Puerto Ricans, like Carlos, because they are Americans with a Latino personality.

Luis and Miguel don't find it odd that there is an American in their class. "Spain had Puerto Rico before the United States," says Luis. "He's Spanish like the rest of us. Plus the Americans can't tell the difference. They think we're all Mexicans. So we have to stick together. Once we're all here, we're all Latinos and we have more in common than we do different."

Carlos pokes the two of them in the arms and flashes his broad smile. He has the same goals they do even though he's not from a foreign country. He doesn't want to be reduced to working in a toy store again. He is scheduled to take the Florida sheriff's exam for the second time. Back in Puerto Rico he passed the police test with a score in the high nineties. Here he got a seventy-three on the sheriff's test when he needed an eighty.

"There was this word all over the test, 'accurate,' and I thought I knew what that word meant but I didn't and it was a problem. Everywhere I looked it said accurate and accurate and accurate and every time I thought I knew. When I was done I went home and looked it up and said, 'Oh, no.' I had messed up so many questions," he remembers. He thought he'd do better since he was educated in Puerto Rico, but the words tripped him up. His computer is always on a translation Web site now. Gabriela Lemus, a policy director for the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), studied the growth of Latinos in Orlando in 2003. She found that the school system there had reached a "critical mass" because of the large number of Latinos who don't speak English. As the Puerto Rican community grew in the nineties the number of students nearly doubled, and they didn't have the resources to keep up. Now, nearly one-third of the Latino population in Orlando is under twenty and parents are not in agreement as to whether they want their children immersed in English or taught to be bilingual.

LULAC thinks part of the problem is that Puerto Ricans don't have the political clout to get the resources they need. Island Puerto Ricans vote in much higher numbers than those on the mainland. Turnouts are so low in central Florida that the island government runs voter registration drives in Orlando. Another problem is that the broader Latino community is not united.

"Orlando has not really experienced any major crisis affecting Latinos. Orlando Hispanics have yet to witness a backlash that would cause them to depend on one another for support," says the LULAC paper titled "Orlando, Fl: A Study in Hypergrowth." "… Discrimination is exhibited more subtly and is primarily based on accents and language."

We caught up with Carlos again when he had gone to his fiancée's apartment to study. He sits at her kitchen table with a stack of dictionaries, this big cop thumbing through these delicate language picture books full of words he can't say. His life has become all about learning English and passing that exam so he can put together a life for his fiancée.

Carlos met Keila Pagan, a newly arrived Puerto Rican, at a bar in Orlando. He was out with a friend who was drinking away his marital problems and the two of them got very drunk. He said he came on too strong but managed to extract a cell phone number from Keila so he could apologize the next day. Seven months after the bar encounter, she is expecting a baby, he is calling her his fiancée, and the language classes feel a lot more pressing. She doesn't speak much English. He thinks they'll need it to take care of their new family in Orlando and she is due in seven months. The pressure is on.

The walls of Keila's apartment are bare except for her bachelor's degree from the University of Puerto Rico in elementary education and her teaching certificate. The books are all English-Spanish dictionaries except for the one about taking care of your new baby. In between homework assignments, Carlos pulls food Keila has frozen for him out of the refrigerator and runs hot water over the plastic container. He's been eating a lot better since she came on the scene. She has left him steaks with Puerto Rican seasonings and yellow rice with instructions on defrosting and cooking and reminders to leave enough for her to have dinner when she gets home from work. He runs off to the gym every so often to make up for the fact that he's gaining weight. There's no point in passing the sheriff's test if he fails the physical. Then he races back to study some more. Carlos misses Keila. She sends him texts on his cell phone telling him she loves him. "I love you more," he responds. He usually picks her up and drops her off at home before going to his language class.

Keila is twenty-five and comes from a very small town called Cidra. She graduated from college just two years ago and left the island because she couldn't find a teaching job. She is licensed to teach K-to-3 kids but she was making $5.25 an hour at a Subway. Her best friend had a great job at an engineering firm in Orlando and had just married one of her Puerto Rican coworkers. They offered her a place to stay so she moved in with them. Then Keila got a job at Wendy's earning $7.25 an hour. There were not many Puerto Ricans where her friend lived and she felt out of place. So she got her own apartment closer to Orlando where she didn't really need to use her English. She could hop on these bright purple buses stamped LYNX by the Orlando transportation system and be among other Latinos in a few minutes.

Once Keila solved the problem of where she lived, work became a stumbling block. She says she was shocked at how racist people are. At least one person every day asked her if she was Mexican derisively. When she told them she is Puerto Rican they'd smile awkwardly like she had some nerve making a distinction. There were a lot of black customers and she expected them to be nicer since she knows many black Puerto Ricans. But they seemed to have the same low opinion of Latinos, she said. There were no Latinos when she started working. But every time there was an opening, one would get hired. She thought maybe the whites and blacks resented the Latinos for getting the jobs. But as the months went by, she rarely saw blacks or whites applying for the jobs. She understood everyone's English perfectly, but when it came time to talk back she would just freeze. It was hard for this teacher to admit she had a lot to learn about language. "I get all the concepts and words but it's so humiliating to talk it," she said.

Carlos picks Keila up at the Wendy's most evenings before leaving for his class. She begins taking off her uniform as soon as she hits the sunlight. When they walk into her apartment, she opens all the blinds and the room brightens. "I know everyone says this but I came for the weather," she says, laughing. "I grew up in sunshine. I need sunshine." Carlos mentions that he would have moved in with her instantly. Carlos's brother and his wife moved to Orlando after his brother got a job as a chef at a Disney restaurant. His sister-in-law was pregnant and by then so was Keila. They were both beginning to feel like Orlando was a new hometown. When they are home together it all feels right.

Keila says she would go back to Puerto Rico if it wasn't for Carlos and the baby. "The Americans make so little effort it makes me angry and I don't like being angry," she said. "I know it bothers them that I don't speak great English, but I grew up in America speaking Spanish so I don't understand what they're so angry about. At least I'm making an effort. They could also try. When they come to San Juan on vacation, they speak English and expect you to speak it back. I don't go to Orlando and expect them to speak Spanish back. I try to speak English. Then they get all indignant that I'm not fluent. They treat us like we're from some other country, like foreigners. I can't even imagine what it must feel like to be a real foreigner.

"People seem to resent us for getting jobs in our own country. What am I supposed to say to that? I didn't come here to fight with anyone. I'm moving from one place to another in my own country," she said.

Keila says people are offended by her pride in her Puerto Rican roots. She got her driver's license and put down her two first names and two last names because that's the way Latinos use their names. She says she wants her child to be fluent in Spanish. She has tried to make friends in the United States but isn't comfortable with the culture. In Spanish Keila is an entirely different person than she is in English. She is bright and well-spoken and pronounces her words with the caution of a language teacher. She had hoped to teach Spanish in Orlando but doesn't want to apply for jobs while she is pregnant. She thinks Anglos and even other immigrants can learn nice things from Latinos and should. She is very much against assimilation. "Assimilate into what?" she asks me. She thinks that Anglos are always rushing around and have the type of parties that start and end at a certain time. She complains that everyone stands around talking about themselves or where they work. No way. It's much better that they learn to have parties where you don't have to ask if you can bring your family and where people never even know what your job is. She would rather be at parties where you can "dance, cook, make good jokes and have enough fun to drag the party out until the sun rises."

Keila is going to take the same language class that Carlos is enrolled in because she wants to speak better English.

"I know I'll be teaching here eventually and that if I were in Puerto Rico my name would be on a waiting list forever," she said. "That's what's great about the mainland. You can be whatever you want. But it could be so much better here if they'd stop resisting integrating us. They're so afraid we're going to change them that it hasn't occurred to them that we just might change them for the better!"

Keila is due for her second appointment with an ob-gyn since she confirmed her pregnancy. The first exam didn't go well. She and Carlos thought they were going to get a sonogram but they misunderstood what the doctor said. He spoke only English. Carlos spent the first exam frustrated and didn't ask the doctor any questions and Keila said it left her wanting to go back to Puerto Rico. LULAC's study found vast discrepancies in health care between Latinos and Anglos in Orlando, even as the community actively recruits Puerto Rican medical service providers. "Barriers in language and communication barriers have resulted in all the misdiagnosis of many patients," says the report.

For their second appointment, Carlos drives Keila early in the morning to the Seminole County Health Department, where a new clinic offers health care to expecting mothers. Mike Napier, the administrator there, used to be married to a Colombian woman and is very sensitive to the needs of Latinos. A few years back, he noticed a sudden rise in infant mortality in his county and became concerned. The number of Spanish speakers having babies was on the rise and he was afraid they weren't getting enough information on prenatal care. So he got funding to bring in private physicians who specialize in obstetrics and made sure that several of them were bilingual. One of them was Dr. Juan Ravelo, one of those tall, handsome Cuban doctors who affirm the positive Latino stereotype that gets pinned to Cubans.

Dr. Ravelo greets Keila and Carlos in Spanish and clears up some misinformation from their last appointment. She is eleven weeks pregnant, not far enough along for a sonogram. She has a rash on her arms that is related to the pregnancy but can be treated with cream. She and Carlos are all smiles when he says he will be seeing them going forward. A Puerto Rican nurse goes over prenatal care with Keila. Then Dr. Ravelo asks her to lie down and brings out a heart monitor. A few slurpy sounds later and a clear, fluttery fetal heartbeat pounds through the monitor. Carlos's eyes fill instantly with tears and he squeezes Keila's arm. "Te quiero. Te quiero," he tells her and kisses both sides of her face and then the top of her head.

"I really need to learn English," he says between big smiles. "I'm having a baby here. I'm going to raise a baby here. I need to know how to say more than the baby in English!"

"Me, too," Keila adds softly.

That evening, Carlos's family gathers at the small apartment given to him by his grandmother. His brother's wife had her baby just a month ago so Carlos's parents flew in to surprise their sons and meet Charlene Gabriela Robles. Seven adults surround this tiny little girl with fuchsia pajamas talking baby talk in Spanish. This is a family that is deeply connected to their children. Carlos's father, Carlos Robles Figueroa, named his sons Carlos Osvaldo and Carlos Alberto.

To have both his sons move to Orlando has been a mixed blessing for Carlos's father. He and his wife have traveled all over the world, enjoying their retirement from being full-time parents. They are glad to see their sons working hard, pairing up with nice Puerto Rican girls, and giving them grandchildren. But the apartment complex where the grandmother Lydia bought her units has converted from a place for retirees to a rough complex filled with gang activity. Carlos woke up one night to find two dozen teenagers attacking each other with shovels. Some of his neighbors own pit bulls for security. Everyone is worried about crime. Carlos's father also worries about what living in Orlando will do to his sons' self-esteem. He is a professor of Puerto Rican and U.S. history at the Inter American University of Puerto Rico. Puerto Ricans are fiercely patriotic and it irritates them when people treat them like anything less than Americans.

"We have been U.S. citizens since 1917. We have fought in every U.S. army since World War One even though we cannot vote for the U.S. president or Congress. We are fighting right now in Afghanistan and Iraq," says the professor, whose English is stronger than that of his two sons.

"The relationship of the United States to Puerto Rico has been one of mutual love and mutual need. It's deeply insulting that so many people here don't even know where Puerto Rico is and keep thinking we're a part of Mexico, which couldn't be a more different place. It amazes me how critical they are of us for not speaking better English when we were educated in American schools. They should be mad at the schools. It doesn't even occur to them that maybe kids on the mainland should be taught to be fluent in Spanish too since so much of their country has Spanish speakers now. I know my sons will learn to speak better and move forward. But I have no interest in them losing their Spanish or their culture because both things are part of what it means to be American to us."

His sons and daughters-in-law nod respectfully as he speaks, then turn fourteen eyes to the seven pounds of baby girl at the center of their discussion. "Que mucho se espera de ti nina bonita," says her father. How much we expect from you, pretty girl.

The language issue has been more than just an obstacle to some Puerto Ricans who have moved here. Roberto Cruz of the Legal Advocacy Center of Central Florida tells of a case where dozens of Puerto Ricans were targeted by a shady lending scheme because of their weak English skills. A company called 4 Solutions promised to refinance homes of owners who were having trouble making payments. In some cases, they'd even take over the mortgage for a few years. Borrowers were promised that their payments would ultimately fall. They signed refinance papers but realized later that they'd actually agreed to sell their homes to investors who believed 4 Solutions would pay the mortgage. When the company didn't pay, the homes fell into foreclosure. The original owners couldn't buy them back because the mortgages had grown. "Language was definitely an issue here. These people were told they were refinancing but the paperwork said they were signing away their equity," said Cruz, another Puerto Rican who relocated to Orlando.

"You would think Puerto Ricans would know better English but it's a myth. A lot of Puerto Ricans, especially ones who are poor and have less education, don't speak and read the language strongly enough."

One of Roberto Cruz's clients is Paula Rivera from Bayamon, who moved to Orlando in 2000 to care for her sister, who was suffering from Alzheimer's. In Orlando she felt like she could improve her quality of life. She earned $10,000 from the sale of her house on the island and signed a rent-to-buy lease in Orlando. She heard an ad on Spanish radio about "great rates" and how you could save money. She was promised her monthly payment would fall from $965 to $600. She didn't figure it out until she got a call from a guy named Vincent Vasquez who claimed to be the new owner. Now she is living there with her sister and a grandson and is counting on God and Roberto to keep her from losing her home.

"The problem here was everything was in English and I speak so little English," she said. "They spoke Spanish and I thought I could trust them."

For others, the gamble of moving to Orlando has paid off handsomely. Haydee Serrano speaks very little English but she was making a living in Boston when she embarked on a vacation to Disney with her two sons and her four-year-old daughter. She had left Puerto Rico years ago searching for opportunities. "It was so cold in Boston," she said. "I didn't get the culture. I had a great job but I was really very unhappy. My kids and I didn't like it there." She was only in Orlando two days before she knew this was the place to be. The suburbs reminded her of the sprawl near San Juan just off the highway. A few weeks later, she had moved her children to Florida with no job, no money, and no prospects. She spent her first months living in a seedy hotel cleaning toilets at a chain restaurant. But five years later she owned a home and belonged in a community.

Haydee's daughter celebrated her fifteenth birthday, her Quinceañera, at Disney. The theme park is marketing the parties to Latinas in expensive packages that can run tens of thousands of dollars. There are carriages and Disney figures and fireworks, as magical as Disney itself. Mirroring what we found when we looked at these ceremonies in Miami, to Haydee, it was as much a celebration of her family's success as it was her daughter's birthday. Even the staff cried to see how proud the stout woman with the thick accent looked escorting her princess at the place of magical dreams. Haydee's son just moved into her house so she races home to cook him rice and beans each night. She says she has been touched by good fortune. She recently got her hours cut back at the job she has as a medical assistant but she took on foster children anyway. She feels like it's her way of returning the help she got when she first moved here.

The trouble some Puerto Ricans have communicating is only a hurdle for some Puerto Ricans in Orlando. In fact, in the 2000 census, 63 percent of all Puerto Ricans in central Florida claimed they could speak English very well. But it's not the only hurdle they face. Vionette Pietri moved to Orlando in 2003 to preserve family ties. Her nephew is her closest relative and he lived in Orlando.

"Family is everything to Puerto Ricans," she said. "It didn't matter that I was giving up a job as a lawyer working for the president of the Puerto Rican Senate." Vionette estimates that she sent out a hundred résumés and got two job interviews. She has a command of English but she speaks with a very heavy accent, which affected the way prospective employers looked at her. Finally, someone suggested she just take her law degree off her résumé. She got a job as a secretary and typed so much she began to suffer from carpal tunnel syndrome.

Vionette was bored out of her mind so she started to teach dance classes. They became the thing she looked forward to each day and she ended up starting a dance school. She used dance to empower women like herself who were struggling. Soon she extended her work to victims of violence. That led to a traveling theater. And then a book: Detras del Velo... Descubre la Diosa en ti (Behind the Veil: Discover Your Inner Goddess.) By the time the book was finished she'd tapped a network of professional Puerto Rican woman and found a job helping educate Latinos on housing rights.

CNN videotaped Vionette's book launch at the large Hispanic Business and Consumer Expo in Orlando that draws an estimated thirty thousand people each year. Vionette was over the moon that day. What a turnaround in just a few years. She is most proud of the fact that she did not compromise her ethnic identity to get to where she is. Her Spanish has ended up being more of an asset than her English. She is doing a show on Spanish radio and writes a column for La Prensa, the local Latino newspaper. This summer she will direct a monologue as part of her traveling theater project.

If Vionette's journey has taught her anything, it's that Latinos have to help each other. She is helping her office promote a program to help people buy foreclosed homes. "I am hoping I'll meet another Puerto Rican woman who needs help," she said. "That is the most important thing to me, to help people the way I was helped." She uses her English at work a lot these days and with each day her pronunciation gets better. "I'm fitting in here more and more each day," she says. "But on my timetable. For now I'm fine working with my own community."

The Business Expo is a reflection of how much the community has changed to accommodate Latinos. The local newspaper the Orlando Sentinel now has a section for Latinos and publishes El Sentinel on the Web. Telemundo and Univision have stations in Orlando. LULAC estimated "there are more than 12,000 Hispanic-owned businesses in Central Florida with almost $960 million in sales receipts. No business has centered on Latinos so successfully as the area's largest employer, Disney."

At that same fair, Vanessa Robles is all smiles and corporate-speak. She is another Puerto Rican who relocated from Orlando. She was studying engineering with her then fiancé in Wisconsin. About eight years ago they traveled to a job fair in D.C. and visited the Disney booth. Disney hired them both in a short time. They moved to Orlando and bought a cute house with three big bedrooms so they could start a family. Then they had two little girls. They had the life they had always wanted.

We came to visit Vanessa in her sixth month of serving as Disney's ambassador. The designation is a major honor at Disney because employees have to compete in an American Idol-type contest for a chance to publicly represent the entire company. To Vanessa, Disney is a dream maker of giant proportions and she has become its chief cheerleader.

The day we go to interview her, everything is scripted as if we were seeking an audience with the Queen of England. Disney is like that. We are escorted by a legion of smiling "cast members" whose mandatory pins identify their place of origin and any special language skills. Vanessa's pin says "Puerto Rico" and "Spanish." To enter the area called Team Disney, which is backstage at the Magic Kingdom, you have to show ID, drive over a moat, and wait for a guard to raise a tiny metal security drawbridge. Once inside, everyone snaps into character and you begin hearing the constant background music of the various Disney theme songs. Yet for all the regimented appearances, there is always a sense of fun in the air. Disney employees are taught that their workplace is a theater, not a theme park. They are all actors in one enormous play and the estimated 200,000 people that walk across their stage every day are treated to a perfectly choreographed show. When you mix the easygoing manner of the Puerto Ricans with the intensely friendly Disney culture, you get Vanessa Robles.

Vanessa arrives for our interview dressed in her "costume," which today is a cherry red business suit with patent leather pumps, a gold Disney broach, and, of course, her name tag, which her PR handlers keep reminding her she is never to take off. She is all smiles and patience as my staff erects three high-definition cameras and lights of all sizes smack in the middle of a lawn in front of the main castle. We are traveling with three photojournalists, Dom, Greg, and Rich, who could be ripped right from the catalog of men who carry cameras. They have classic good looks and large muscles and tweak every light and lens as if they were fine cars.

Everything is timed like clockwork to be finished before the park opens. The carefully manicured lawn is brushed into shape, the walkways sparkle, the team assigned to us has made sure we are all in position and our gear and cars are tucked away so there is no danger a guest would see any mess. One of my producers, Kimberly Babbit, another perfectionist, has been working on this shoot for weeks. She is a very tall slinky blonde whose serious black suit can't hide the fact that her looks draw universal attention. Everything and everyone associated with this day is ripped right out of central casting.

But when the time comes for all this to play out, one of the PR staff is failed by her GPS and gets lost. Instead of being guided in before the park fills, I arrive just as the crowds are pouring into the Magic Kingdom. I begin dashing off questions as everyone hustles into position. Kimberly has worked every angle of a production shoot to get it right and she is suddenly ashen from the stress. The PR folks are huddled around a monitor discussing how everything is going to look with all these unexpected people. Then things go from bad to worse. Neither Disney nor Kimberly is able to control the weather and the clouds bunch together above us as one of those unmistakably Floridian tropical storms begins pouring rain on everyone. I just can't stop laughing inside.

From here on, everything careens further and further off script. We abandon the interview and hop on a horse-drawn carriage to avoid the drizzle. Greg the camera guy hops aboard just as the cast begins belting out "someday my prince will come." We try to continue the interview over the loud clippity clop of the horses. Then the skies open and I am asking Vanessa about Puerto Ricans in Orlando in the middle of a major weather event.

Back at the setup, Dom seems to be the only one wearing rain gear, but he still looks like a wet puppy and a strong frown is etched on his face, his arms shielding tens of thousands of dollars' worth of equipment as Kimberly races around in stiletto heels throwing trash bags over everything. We do a loop with the horses and race over to the teacups to find shelter. There is yet another Puerto Rican staffer, who gets us into the ride, so we hop on with Greg spinning backward recording us as we lurch forward. The spinning usually makes me nauseous but I'm laughing at the whole situation.

Around and around we go in a giant teacup as I ask Vanessa to explain how she has devoted herself to shortening the lines and organizing food service, things you don't typically associate with engineers but that require near brilliance at a park so large. Her functions are truly critical. Her team invented the Fast Pass, which lets you jump the endless lines, priceless for any parent with crabby children in tow. We ditch the teacups and charge over to the train station, where thousands of visitors pour out despite the rain. Plan B is to continue our interview up on the platform, which is covered.

Vanessa was chosen by sixty-one thousand cast members for her ability to keep that smile beaming and she is doing a great job. There are Puerto Ricans everywhere and she is as proud of them as they are of her. Of all of us, she's the only one still looking good. "Every day you have a whole new conversation here about how you miss your hometown," she tells me as we duck for cover in a Germanic-looking bakery. Kimberly and the team have raced ahead to the platform to scout our next scene. My hair has gone totally limp and my black suit is hanging off my shoulders from the weight of being wet. My hairdresser Wendy has stopped following me around with a comb. The humidity is so strong that the air is wet between the raindrops. Vanessa and I chat and I compliment her on her clear English. Her accent is so slight, it is charming.

"How do you maintain your Puerto Rican-ness?" I ask her.

"We both speak Spanish at home. We try to maintain our Puerto Rican cooking. We buy cookbooks. My kids love eating plantains even more than they love French fries. They love singing to our music and dancing."

"What's the best and worst thing about moving to Orlando?"

"Being part of a Fortune One Hundred company that values diversity," she says, very much on script but with sincerity. "The worst, well, I miss my family, my friends. I miss the festivals. There is a festival in Puerto Rico almost every week."

The rain has now been joined by a gusting wind that pushes the raindrops at odd angles. The Disney staff is suggesting every possible solution. I want to hug them for all their hard work, but we are clearly not going to have a formal, well-lit, sit-down interview outdoors today. Someone suggests we go to Vanessa's house and she eagerly agrees. Greg is soaked and wants his delicate microphone back before it is totally waterlogged. The equipment is scattered everywhere under plastic tarps. But the show must go on. So we jump into a caravan of cars and race away from the Magic Kingdom. When I hear about the tenth person wishing me a "magical day" I'm slightly in awe of how terrifically they run this place. I begin having fantasies about how they might manage my whole life for me. Maybe then I would be having a magical day.

Vanessa lives in a development called Heritage Place, not far from a few neighborhoods that are solidly Puerto Rican. Hers is a mix, but it looks a lot like Bayamon on the outskirts of San Juan. Some of the houses are painted in those soft Caribbean blues and yellows and, inside, she has prints on her walls of Old San Juan. Andrea, five, and Paola, two, are at a day care that has a pre-K program but their presence dominates the house. The bathroom is decorated with bright pink Disney princess curtains and pink bath towels. Toys are arranged very neatly in every corner. Picture portraits peek out from all the walls. The entranceway is dominated by some very large pictures surrounding a wedding picture in which Vanessa smiles that now familiar smile.

We settle in the living room, where a picture is hanging of a river in Barceloneta where her husband was born. They were both Puerto Ricans making their way on the mainland when they met and came to Disney. As an engineer she was bedazzled by Disney's efficiency.

"This is a costume and we are all cast members," she says, referencing her own business suit. ". . . It's someplace clean . . . where you can escape reality and come into fantasy. It's a show and we are all part of the show."

We're hungry after our exertions so we order take-out Cuban food and the air fills with the smell of garlic and fried meat. But we have to let the food sit there and taunt us because we still haven't done the interview. So, about seven hours after my staff got up and a full fourteen hours since I boarded a plane from the West Coast to get here, we finally sit down for our formal interview. I'm hungry and a mess but Vanessa looks perfect. The only people checking to see how it looks are the Disney team.

Vanessa acknowledges Disney has had an aggressive recruiting effort of Puerto Ricans for years and says that's about its broader effort to keep its workforce diverse. It doesn't hurt that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, absent immigration issues and many times bilingual and well educated. They have the right attitude, love the fun of Disney, and appreciate the warm weather. Disney is Orlando's biggest employer and a lot of Puerto Ricans have moved there with this dream in their heads that they would get a job there.

Vanessa's Orlando experience has been the flip side of Carlos's hard road. She senses no hostility and respects people's expectation that she speak strong English. She feels like Orlando welcomes diversity. She attends mass in Spanish and feels a sense of warmth and family around her that she needs. She feels free to maintain her culture in her own home. "Puerto Ricans. That is who we are. We have a heritage that is very rich," she said.

So she has taught her girls about Three Kings Day and how they will get presents if they put grass beneath their beds for the horses. They travel "home" once a year. She shrugs off her mother, who talks to her daughters on the phone and remarks that they don't have a proper Puerto Rican accent. She cooks plantains for them and reads books in Spanish. "Para atraz ni para coger impulse," she declares. Not going backward even to gather speed.

The storm outside has retreated back into the clouds. Vanessa is charming. This job and this place have given her the life she dreamed of having. She has been able to preserve the culture and language she loves so much and has not had one bad experience in this town. She is more nerd than automaton, truly accomplished and a great face for Disney. I like her. She is genuine in both her happiness and her commitment to her job and the life it brings. She is the living, breathing reason for why all those thousands on the island just up and left for Orlando. She represents the possibility of Puerto Rican portability, the notion of taking your culture "to go." We wolf down our heavy Cuban carryout because sometimes a Cuban girl like me needs a load of picadillo on a bad day. Then we head out.

We catch up with Carlos at his fiancée's apartment. He still hasn't moved in but he's slowly bringing his stuff over and insinuating himself into the place. His anxiety has grown at the same pace. Before even saying hi, he announces he really doesn't want us to tape him retaking his sheriff's exam. He is afraid he might fail. The last time he took it he says he scanned the room looking for a group of Latinos to sit next to but found no one. He got very anxious.

"I want to pass the test. I love this job. The security, the police, I want to be it again," he says.

"What's making you the most nervous?"

"I think it's the language," he says, his speech a smidge better than it was a few weeks back.

Carlos has been practicing diligently for months. His only time off is the time he takes to get to know his fiancée better and prepare for the baby. But he has no money and doesn't really know what to do other than be nervous and try to take care of Keila, who seems to be sleeping thirteen hours a day. She's getting cravings, waking up late and demanding he get her ice cream. She's very specific that it needs to be from Cold Stone Creamery, not the Baskin-Robbins closer to home. It's driving him nuts. She is rapidly growing their baby while he is intensely studying the rules for use of force, gang terminology, and quantities of illegal drugs needed to violate certain statutes.

The large empty living room feels like it's closing in on Carlos. He has four hours to answer 250 questions and he says if he spends too much time on any one question, it's curtains for him. Yet he is taking way too much time reading each question because his English comprehension is slow.

"Do you feel like you have a lot of stress on you right now?" I ask.

"Ah, yes." He inhales when he talks, as if letting out any breath makes it harder to talk English. If all this wasn't enough, Keila doesn't look happy and that bothers him. "Sometimes she feels like I do. That it's hard because she is getting a master's degree here and she can't work and get a good job," he says.

He was earning $24,000 in Puerto Rico, maybe $32,000 with overtime. A sheriff's salary would start at $39,000. She is fourteen weeks pregnant. If he fails the test, he can either give it one last try or give up and redo the entire police academy experience he had back in Puerto Rico. Neither choice is a good one, as it means additional weeks with no income and he's already feeling the pinch now. There is a baby on the way, he repeats again. He has to pass this test.

We follow Carlos to language class, where he begins by desperately asking the teacher if he would qualify for the intensive, faster class that meets several mornings. She tells him he's not there yet and his face falls. Today's topic is controversial issues, so they begin to recite phrases. "Let's raise the voting age," they chant. "Raaazing da boting ach." The Venezuelan commander looks more frustrated this time. He is very tired of being the pool boy and also wants to move up.

"If I can get a better level of English I'm hoping some doors open up for me," he says with a markedly reduced accent from just two weeks ago. Carol Traynor, the communications director for the college, tells me that some of these students are paying to take this class two, three, and four times. Everyone in the room is taking the course again after this session ends. The levels have optimistic names, like Intermediate Level A, B, C or Advanced Lower A. There are steps to climb in this process. Hundreds of students are taking them at any given time and the stakes are high for every one of them. I leave Carlos clutching a spineless workbook and calling out his drills with vigor.

That evening I book a room at a Disney hotel that is designed to look like a Polynesian village. You have to walk outside to travel between the many little buildings, which means walking in the aftermath of the morning's storms. The sprinkler system turns on automatically so it's fighting for attention with the rain. Small torches illuminate the walkways that are studded with these poles that look like totems. Everyone is walking around in flowery costumes that make them look like they might be in search of a spear. There's something uniquely American about dressing up working adults in funny costumes. The décor inside the rooms is very similar. Bedspreads with turtles and lamps with fake wood painted with the face of some sort of native.

The scene drives me to the bar for a Polynesian drink. Even the bars at Disney are full of children on vacation. The cacophony of voices with an undertone of children's music makes the place feel like it's humming. Even here, you see Puerto Ricans popping up all over the place. Either that or I've become acutely aware of Puerto Ricans in Orlando. They race around in Polynesian dress seating customers at the jam-packed restaurant or swiping credit cards at check-in.

This is one of the places Carlos has applied to work in case he doesn't pass his sheriff's test, in the massive hotel industry connected to Disney. His brother is already a chef at one of the restaurants.

They get a kick out of the costumes and the free-flowing laughter of people on vacation. They are silly guys and the silliness of all this stuff entertains them. I hope he passes his test, but it's a lot easier to picture him here rather than pulling over drunk drivers or muscling down a gang member.

The day he retook the test, Carlos already looked like a police officer. He was wearing his mirrored sunglasses and walking around with that confident cop swagger. But he was nervous, very nervous, and he was chain-smoking menthol Marlboro Lights.

Carlos had so much riding on this test he'd already failed once. He walked to the waiting area at the Volusia County Fairgrounds and stood apart from the other men and women. He smoked. He tapped his two number 2 pencils against one another. And he paced. He was an hour early for the 10:00 a.m. exam. He looked like a prizefighter about to enter the ring. When it was time to register he handed his glasses and cell phone to Kimberly, my producer, and said he'd see her in four hours before disappearing into the exam room.

The results were posted quickly, online. Carlos was almost as nervous as he had been the day he took the exam. He felt like he'd done better but bad news was pouring in like rain. Another potential job prospect at Disney had gone nowhere and he had not scored high enough on his English Pronunciation class to move to a higher level. His fiancée has her first sonogram in just two weeks. When the news came it was like those gray clouds that billow in the sky when it looks like it's stopped raining but really hasn't. Carlos had failed.

He walked somberly to tell his fiancée. Carlos needs a job. He needs to speak better English. Now he needs to take this test he's studied so hard to pass one more time. But there are some parts of his life that offer him certainty. He is staying in Orlando. This is where he lives now. He is not going back. Maybe he'll apply for a job at Disney. He's a sweet guy and his accent will matter less in a world where people are striving to have a magical day. I can almost picture him walking around the place, dressed in a floral shirt, and saying, "AH-LOH" over and over again.

He has been in Orlando for two years and so far only the most extreme winter chills (extreme, that is, by Orlando standards) have rattled him. Puerto Ricans are the only U.S. citizens born on a piece of U.S. soil where Latin culture and the Spanish language are dominant. They are not immigrants or the children of immigrants like all the other Latinos. Since 1917 they are U.S. citizens and, despite their island's colonial friction with the United States, they are basically Americans born and bred. Taking a trip to Puerto Rico, lovely as that might be for me, isn't going to tell me much about Latinos in the larger American experience because the island in many ways operates like its own Latino country. So, instead, I've come to Orlando, Florida, a favored destination for islanders looking to come to the mainland.

I meet Carlos in the sun-splashed garden of the Valencia Community College Center for Global Languages, where Carlos is taking a class. Students from all over the world study here to improve their pronunciation and understanding of the English language. They used to call the classes Accent Reduction but no one enrolled. So they renamed them English Conversation class and now they're full.

Carlos is a fair-skinned, chunky guy with short dark hair and a squared-off goatee. He is sweating and antsy and shakes my hand like he's just walked into a do-or-die job interview. When he says, "Eh-lo," I think of my grandmother with her two words of English. I tell Carlos that I know Spanish but that if I were to talk to him in Spanish he'd be doing this story about me. He starts smiling little by little. I recall how my mother used to say "hog-dog" all the time for hot dog and get a snicker of recognition out of him.

Carlos's features could make him from anywhere Latin, except that his Spanish is very Puerto Rican. When he speaks Spanish he replaces his rs with ls and he talks like he's about to start singing. It's a happy form of speech, very homey, almost like teasing. But in English he sounds like he's spitting out phrases. He is hesitant, throwing out each word almost like he's asking the question, "Is this the right word, am I pronouncing it right?" So this guy who was born on American territory, educated in American schools, is about to begin barking out language drills in a classroom so he can communicate with his fellow Americans here in Orlando. He laughs at his whole situation.

I meet another Puerto Rican student in the garden. Santos Martinez is tall, black, bald, and looks like the basketball coach he is. He coaches in English but feels like he's not communicating with the parents. "I can't do that if the fathers keep looking at me like, 'What did he just say?'" says Santos. He rattles off his personal résumé to explain why he's here. "I'm part-time [at] JetBlue, no wife, no kids. In my culture that's a loser." His language limitations have kept him from rising professionally or meeting the American wife he's looking for. Santos, Carlos, and I trade words before class begins. Carlos can't say the ths properly. Instead of "thought," he says "tawt." I ask them what's the most difficult word to pronounce in English and Santos says, "Crocodile." I ask him how you pronounce it in Spanish and suddenly we're all standing there sputtering: "Co-co. Ca-ca-ca." We all begin to laugh.

Carlos's journey to Orlando began in his hometown of Fajardo, known as La Metrópolis del Sol Naciente, the Metropolis of the Rising Sun. It's a small town on the east end of Puerto Rico where recreational boats float in the Atlantic Ocean and big ferries take off for the islands of Vieques and Culebra. Nothing in Fajardo seems to move quickly, not even the cooling breeze that comes off the ocean. Like Orlando, it's a place many people associate with a good vacation.

Carlos worked as a police officer in nearby Carolina, where an international airport sits beside a string of resort hotels, lazy beaches, and a very large shopping mall. His territory included the towns of Loiza and Canóvanas, which have housing complexes with substantial drug problems. Carlos felt he was on a road to nowhere good. The pay was low; his family was threatened by the drug dealers; his mother was always praying for his safety. Homes on the island are very expensive so he felt he'd never be enough to buy something nice. He had to get out. But it made him sad to walk away from the tranquility and tropical weather he loved.

Years earlier, his aunt and uncle had moved their family to Orlando after his uncle was transferred there by the navy. There were a lot of Puerto Ricans there and the family found the weather and atmosphere familiar. Carlos and his family visited so often that his grandmother purchased three small apartments to use as vacation homes for all her kids and grandkids. When Carlos decided to quit his job to search for new opportunities, his grandmother offered him a free apartment in Orlando so he could join his aunt, uncle, and two cousins. He was gone in weeks.

This is a familiar story for many Puerto Ricans who relocate to Orlando. The island has 15 percent unemployment and there isn't enough affordable housing, while there are more opportunities for jobs and homes on the mainland. Jorge Duany, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico, researched the phenomenon of Puerto Ricans moving to Orlando. He discovered official efforts to encourage Puerto Ricans to move to Orlando dating as far back as the 1950s, when central Florida needed more farmworkers and the island's government began a program to encourage migration. That was followed by another contract labor program in the 1970s.

Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens and the island had a lot of trained agricultural workers. Since the island had lower salaries, the Puerto Ricans were a cheap, hardworking domestic labor force. The workers made more money on the mainland, bought homes and stayed. Friends and relatives followed. In 1971, Disney opened and real estate speculation drew even more Puerto Ricans. Disney also liked Puerto Rican workers. They sent representatives to the island to visit schools and job fairs. They even offered cash relocation bonuses at one point.

Orlando in general was exploding with people. The local chamber of commerce estimates one thousand a week were coming at one point. Research by the Pew Hispanic Center in 2002 determined Orlando's Latino population had 300 percent growth since 1980. The U.S. census said the place was adding 347 people a day in 2001, and there's no denying that Puerto Ricans were a big part of that growth. They represent 56 percent of the Orlando Latino population, and that doesn't even count the many Puerto Ricans who travel back and forth.

As the population of Orlando became more Latino, other companies looked to diversify their workforce and offer bilingual services. Puerto Rican employees filled both those goals without having any immigration issues. NASA, just forty miles away, sent recruiters to hunt for talented engineers at the University of Puerto Rico in Mayaguez. Florida Hospital in Orlando signed an affiliation agreement with the University of Puerto Rico in 2005. Between 2000 and 2006, according to census figures, 200,000 of Puerto Rico's 4 million people moved to Florida. After the farmworkers came blue-collar laborers and then professionals. They didn't just come from the island but also from big mainland cities like New York and Chicago, traditional destinations for Puerto Ricans. Almost half the Puerto Ricans in Orlando come from other cities on the mainland, Duany found in his research. He also discovered that the newcomers are mostly white, well educated, and have more than double the median family income of their counterparts back on the island. The move is paying off. When Carlos came to Orlando in 2007, he was hoping to become another Orlando-Rican success story. Very quickly he had a job as a manager at Kay-Bee Toys. There were four managers and he was the only one who spoke Spanish, an asset. He was earning good money. He met Puerto Ricans from New York who were looking to move to Orlando because they found their city so cold and fast-paced. Carlos is funny and friendly and gives off the air of a guy who likes to be liked. He tried hard to fit in with the other managers. But they weren't very friendly. Every time he opened his mouth, they would look at him like he was an idiot. "I cried in my bed because I can't have a conversation with the people. It was really bad," he said.

Like all Puerto Ricans, Carlos was taught English in school and expected to speak it fluently. Yet once he left school, there just weren't opportunities to have real conversations in English. His vocabulary and accent suffered. The Puerto Ricans from New York all spoke English and people expected him to speak it, too. But the white people in Orlando would just smile politely and walk away in the middle of a conversation. "I'd look at them and think, 'That guy has no idea what I just said to him,'" Carlos remembers. The other managers at Kay-Bee Toys wouldn't even smile. They would just bark orders at him as if he was their subordinate, pushing him toward grunt jobs and making jokes behind his back. His supervisor called him a Mexican. Carlos thought it was funny because he was considering joining the Border Patrol at the time and the ads all asked for fluent Spanish speakers.

He tried to let their remarks roll off him but it slowly began to get to him. He'd never felt this way back on the island, where he was a swaggering American police officer bossing around a whole group of motorcycle cops patrolling for drug dealers.

"Oh, my God. It was humiliating. I wanted to punch them sometimes," he said. "I just kept telling myself I'd start to speak better and one day I'd be this professional guy they'd look up to."

There are nearly eight hundred students taking the English speech classes at Valencia and it is repeated five times a year. It is a little odd to see Americans taking classes to reduce their accents alongside people coming from foreign countries, but Puerto Ricans are a twist in the discussion of Latinos in U.S. culture.

After Kay-Bee Toys shut down, Carlos decided he wanted to wrap his arms around the language and enrolled in pronunciation class. He is taking a second round, twice a week from 6:00 to 8:30 p.m.

"I'm taking the class because I saw that I can be more professional and I think that I can have a better life and I need to talk English. I'm in the United States, so I need to talk," he said.

"Well, Puerto Rico's part of the United States," I point out.

"Yeah, but we always talk in Spanish. We never talk in English over there."

Carlos looks like he used to have the imposing build of a cop. He wears the reflecting sunglasses you'd expect to see on a police officer who works in warm weather. Inside his classroom, words are written in red that make Carlos's head hurt: kitchen, corner, and victory. Cabinet. Thought.

"The Latinos hate the words with the th and the v," says Marisa Dawson, the teacher. "The Asians have great grammar but they've never had to speak, so their pronunciation is terrible. The Puerto Ricans should know more than the South Americans but they don't. They all learn it in school but it's kind of like learning high school French. If you never use it, you lose it, and when they come here I think they're surprised how much they need it. The South Americans are prepared because they know they won't get anywhere if they can't speak English."

Carlos is sitting between a Colombian guy and a Venezuelan. Neither of them really wants to be in the United States but they were forced to leave their countries. Miguel Ortega was a surgeon back in Colombia and now he's "the cable guy." He tried being a medical assistant when he first got to Orlando but it paid $8 an hour. It is too dangerous in Colombia or he would go back. The paramilitaries killed people where he worked. He is determined to be a doctor again so he is studying to pass the required recertification tests. He has passed the first few but the last one requires English conversation, so he needs this class to work.

Luis Sirit was in the Venezuelan navy as a commander. He also wishes he could go home but he says he is on the wrong side of politics there and that can be deadly.

"I could do just fine in Orlando without learning any English, that's how Latino it is here," he says. "But I'm cleaning swimming pools. I didn't study to clean swimming pools."

Both of the men voice a short list of laments about living in the United States: the food is not fresh, the parties never seem to include music or dancing, the people aren't as close to their families. Luis says he keeps inviting people over to show them how much fun Latinos can be and he says they really enjoy his culture. He especially likes the Puerto Ricans, like Carlos, because they are Americans with a Latino personality.

Luis and Miguel don't find it odd that there is an American in their class. "Spain had Puerto Rico before the United States," says Luis. "He's Spanish like the rest of us. Plus the Americans can't tell the difference. They think we're all Mexicans. So we have to stick together. Once we're all here, we're all Latinos and we have more in common than we do different."

Carlos pokes the two of them in the arms and flashes his broad smile. He has the same goals they do even though he's not from a foreign country. He doesn't want to be reduced to working in a toy store again. He is scheduled to take the Florida sheriff's exam for the second time. Back in Puerto Rico he passed the police test with a score in the high nineties. Here he got a seventy-three on the sheriff's test when he needed an eighty.

"There was this word all over the test, 'accurate,' and I thought I knew what that word meant but I didn't and it was a problem. Everywhere I looked it said accurate and accurate and accurate and every time I thought I knew. When I was done I went home and looked it up and said, 'Oh, no.' I had messed up so many questions," he remembers. He thought he'd do better since he was educated in Puerto Rico, but the words tripped him up. His computer is always on a translation Web site now. Gabriela Lemus, a policy director for the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), studied the growth of Latinos in Orlando in 2003. She found that the school system there had reached a "critical mass" because of the large number of Latinos who don't speak English. As the Puerto Rican community grew in the nineties the number of students nearly doubled, and they didn't have the resources to keep up. Now, nearly one-third of the Latino population in Orlando is under twenty and parents are not in agreement as to whether they want their children immersed in English or taught to be bilingual.

LULAC thinks part of the problem is that Puerto Ricans don't have the political clout to get the resources they need. Island Puerto Ricans vote in much higher numbers than those on the mainland. Turnouts are so low in central Florida that the island government runs voter registration drives in Orlando. Another problem is that the broader Latino community is not united.

"Orlando has not really experienced any major crisis affecting Latinos. Orlando Hispanics have yet to witness a backlash that would cause them to depend on one another for support," says the LULAC paper titled "Orlando, Fl: A Study in Hypergrowth." "… Discrimination is exhibited more subtly and is primarily based on accents and language."

We caught up with Carlos again when he had gone to his fiancée's apartment to study. He sits at her kitchen table with a stack of dictionaries, this big cop thumbing through these delicate language picture books full of words he can't say. His life has become all about learning English and passing that exam so he can put together a life for his fiancée.

Carlos met Keila Pagan, a newly arrived Puerto Rican, at a bar in Orlando. He was out with a friend who was drinking away his marital problems and the two of them got very drunk. He said he came on too strong but managed to extract a cell phone number from Keila so he could apologize the next day. Seven months after the bar encounter, she is expecting a baby, he is calling her his fiancée, and the language classes feel a lot more pressing. She doesn't speak much English. He thinks they'll need it to take care of their new family in Orlando and she is due in seven months. The pressure is on.

The walls of Keila's apartment are bare except for her bachelor's degree from the University of Puerto Rico in elementary education and her teaching certificate. The books are all English-Spanish dictionaries except for the one about taking care of your new baby. In between homework assignments, Carlos pulls food Keila has frozen for him out of the refrigerator and runs hot water over the plastic container. He's been eating a lot better since she came on the scene. She has left him steaks with Puerto Rican seasonings and yellow rice with instructions on defrosting and cooking and reminders to leave enough for her to have dinner when she gets home from work. He runs off to the gym every so often to make up for the fact that he's gaining weight. There's no point in passing the sheriff's test if he fails the physical. Then he races back to study some more. Carlos misses Keila. She sends him texts on his cell phone telling him she loves him. "I love you more," he responds. He usually picks her up and drops her off at home before going to his language class.

Keila is twenty-five and comes from a very small town called Cidra. She graduated from college just two years ago and left the island because she couldn't find a teaching job. She is licensed to teach K-to-3 kids but she was making $5.25 an hour at a Subway. Her best friend had a great job at an engineering firm in Orlando and had just married one of her Puerto Rican coworkers. They offered her a place to stay so she moved in with them. Then Keila got a job at Wendy's earning $7.25 an hour. There were not many Puerto Ricans where her friend lived and she felt out of place. So she got her own apartment closer to Orlando where she didn't really need to use her English. She could hop on these bright purple buses stamped LYNX by the Orlando transportation system and be among other Latinos in a few minutes.

Once Keila solved the problem of where she lived, work became a stumbling block. She says she was shocked at how racist people are. At least one person every day asked her if she was Mexican derisively. When she told them she is Puerto Rican they'd smile awkwardly like she had some nerve making a distinction. There were a lot of black customers and she expected them to be nicer since she knows many black Puerto Ricans. But they seemed to have the same low opinion of Latinos, she said. There were no Latinos when she started working. But every time there was an opening, one would get hired. She thought maybe the whites and blacks resented the Latinos for getting the jobs. But as the months went by, she rarely saw blacks or whites applying for the jobs. She understood everyone's English perfectly, but when it came time to talk back she would just freeze. It was hard for this teacher to admit she had a lot to learn about language. "I get all the concepts and words but it's so humiliating to talk it," she said.

Carlos picks Keila up at the Wendy's most evenings before leaving for his class. She begins taking off her uniform as soon as she hits the sunlight. When they walk into her apartment, she opens all the blinds and the room brightens. "I know everyone says this but I came for the weather," she says, laughing. "I grew up in sunshine. I need sunshine." Carlos mentions that he would have moved in with her instantly. Carlos's brother and his wife moved to Orlando after his brother got a job as a chef at a Disney restaurant. His sister-in-law was pregnant and by then so was Keila. They were both beginning to feel like Orlando was a new hometown. When they are home together it all feels right.

Keila says she would go back to Puerto Rico if it wasn't for Carlos and the baby. "The Americans make so little effort it makes me angry and I don't like being angry," she said. "I know it bothers them that I don't speak great English, but I grew up in America speaking Spanish so I don't understand what they're so angry about. At least I'm making an effort. They could also try. When they come to San Juan on vacation, they speak English and expect you to speak it back. I don't go to Orlando and expect them to speak Spanish back. I try to speak English. Then they get all indignant that I'm not fluent. They treat us like we're from some other country, like foreigners. I can't even imagine what it must feel like to be a real foreigner.

"People seem to resent us for getting jobs in our own country. What am I supposed to say to that? I didn't come here to fight with anyone. I'm moving from one place to another in my own country," she said.